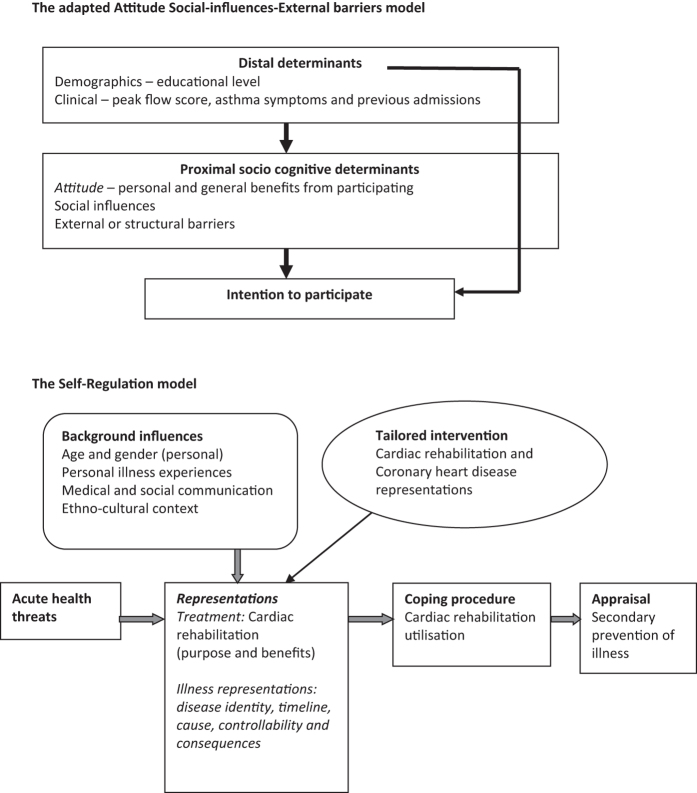

Figure 1.

The ‘best fit’ theoretical models. The adapted ‘attitude–social influence–external barriers' model. Lemaigre et al.16 reported using the ‘attitude–social influence–self-efficacy’ model by de Vries et al. to explain intention to participate in an asthma self-management programme. The constructs as measured by Lemaigre were as follows: attitude including personal and general benefits of the asthma programme. Social influence including social norms to take care of their asthma and motivation to comply with these. Self-efficacy (external barriers) including beliefs about barriers to participate. It should be noted that the definitions of these constructs vary slightly from those used in the original de Vries model (see Supplementary Appendix 2 for further details), particularly that of self-efficacy, which focuses primarily on external barriers and hence is labelled as such here. The figure above illustrates the distal, proximal socio-cognitive and external constructs of the adapted model that explained intention to participate in an asthma self-management programme in the study by Lemaigre et al.16 The descriptive themes and subthemes were ‘mapped’ onto the adapted model’s theoretical constructs. The ‘self-regulation’ model. Keib et al.21 used the ‘self-regulation model’ by Leventhal et al. and the ‘necessity-concerns framework’ by Horne to explain participation in cardiac rehabilitation among patients with coronary heart disease. The self-regulation model explains the effort an individual makes, in response to a health threat, to protect and maintain health and to avoid and control illness based on representations of the illness. The threats (physical and psychological indicators) that disrupt physical and cognitive function as a result of the illness make contributions to the illness representation. Leventhal et al. in the 1990s stated the five domains of ‘illness representations’: 'disease identity' is the perceived symptom experienced as a result of an illness and the symptoms associated with the illness. 'Timeline' is the perceived expected duration of illness (acute and chronic) or expected age of onset of illness. 'Consequences' is the perceived severity and impact on life functions as a result of the illness. Cause could be perceived as internal (e.g., genes) or external (e.g., infection). Control/cure is whether the illness is perceived as ‘preventable’, ‘curable’ or ‘controllable’. These illness representations can lead an individual to generate goals, and to develop and carry out action plans (referred to as coping procedures), which are subsequently evaluated in relation to whether the threat has been eliminated or controlled and influence subsequent representations of the illness and behaviour and hence self-regulation. Horne within the ‘necessity-concerns framework’ stated that 'necessity' beliefs are perceived personal needs for the treatment and 'concerns' beliefs are perceived concerns of the treatment, both of which influence treatment adherence. The figure above illustrates the illness and treatment representations that explained participation in cardiac rehabilitation in the study by Keib et al.21 The descriptive themes and subthemes were ‘mapped’ onto the above-mentioned theoretical constructs. Supplementary Appendix 1 describes how Keib used the model to explain participation.