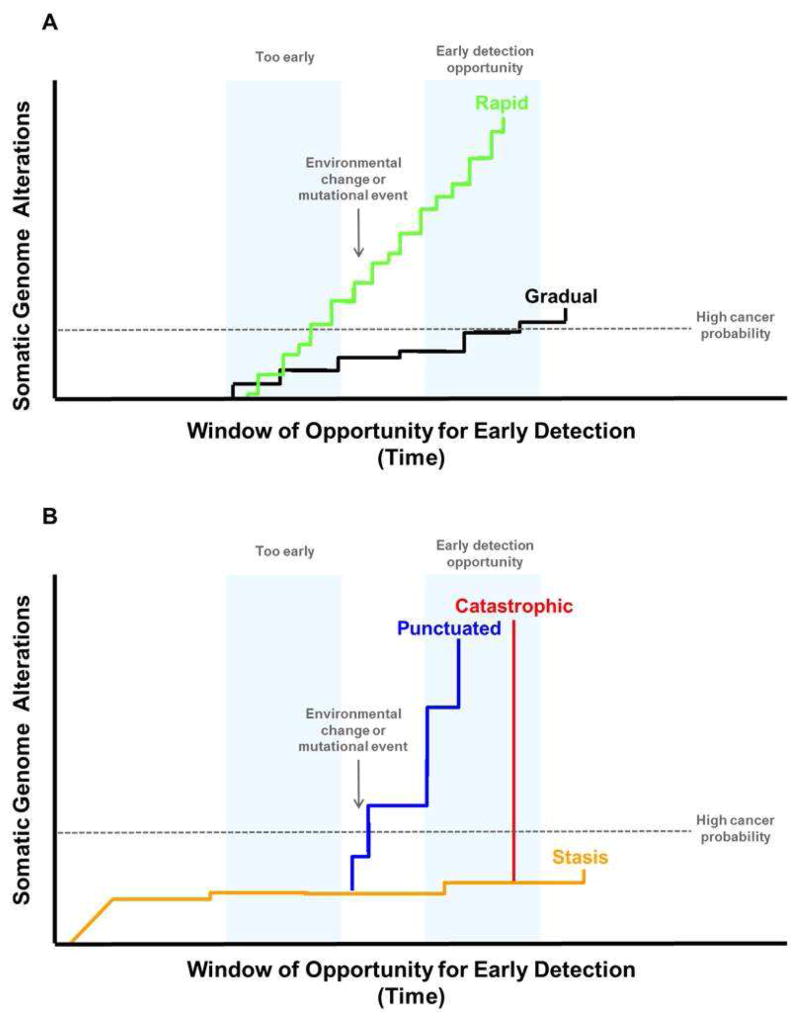

Figure 3. Punctuated and catastrophic evolution can decrease the window of opportunity for early detection.

Panel A. Progression of a neoplasm over time has historically been thought to occur by a slow, gradual mutation rate that would typically take decades to accumulate the genetic changes needed to produce a cancer (“gradualism”). However, recent results from genome analyses of advanced cancers have provided evidence that genomic alterations may occur at vastly different rates. For example, point mutations may occur slowly resulting in relatively gradual rates of progression (black line), but exposure to environmental mutagens such as tobacco smoke (lung cancer) and sunlight (melanoma) as well as inherited conditions, such as mutations that cause microsatellite instability, can increase the mutation rate leading to rapid evolution of cancer (green line). A recent exome sequencing study of a large number of EAs found that MIN was uncommon with only 4/149 that had such high mutation frequencies (2.7%) 47. Panel B. Chromosome instability, which has been historically defined as an increased rate of gain or loss of whole chromosomes or large regions of chromosomes, causes “punctuated” evolutionary jumps (blue line). Some genomic errors involving chromosomes can lead to catastrophic evolution. These include chromothripsis (chromosome shattering) and whole genome doublings, which may occur in a single cell division (red line). A series of events may accelerate progression from punctuated to catastrophic evolution and cancer. For example, BE develops chromosome instability (“punctuated evolution” blue line) within four years of the diagnosis of EA and genome doublings (“catastrophic evolution” red line) that can be detected by SNP arrays within two years of EA diagnosis (red line). When evaluated by SNP arrays, non-progressing BE typically has a limited number of chromosomal alterations that developed before the patient was seen clinically and tend to remain stable for prolonged periods up to more than two decades (“stasis” yellow).