SUMMARY

Aptamers are structured macromolecules in vitro evolved to bind molecular targets, whereas in nature they form the ligand-binding domains of riboswitches. Adenosine aptamers of a single structural family were isolated several times from random pools but they have not been identified in genomic sequences. We used two unbiased methods, structure-based bioinformatics and human genome-based in vitro selection, to identify aptamers that form the same adenosine-binding structure in a bacterium, and several vertebrates, including humans. Two of the human aptamers map to introns of RAB3C and FGD3 genes. The RAB3C aptamer binds ATP with dissociation constants about ten times lower than physiological ATP concentration, while the minimal FGD3 aptamer binds ATP only co-transcriptionally.

INTRODUCTION

Functional nucleic acids fold into specific structures that form the physicochemical foundations for their activity, which includes catalysis and ligand binding. Among the best characterized functional RNAs are aptamers, oligoribonucleotides in vitro selected to bind target molecules with high affinity and/or specificity (Ellington and Szostak, 1990; Stoltenburg et al., 2007; Tuerk and Gold, 1990). In general, the aptamer structures consist of the ligand binding pockets formed by folding of single-stranded regions of specific sequence and flanking helical regions that are typically sequence independent (Riccitelli and Lupták, 2010). When the target is a small molecule, e.g. a metabolite, the aptamer often forms a buried binding site with extensive hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions that give rise to the ligand binding characteristics. The flanking helical regions contribute to the strength of the interaction by stabilizing the ligand-binding structure, but can also be used as transduction domains for signaling the presence of the ligand in the binding site by switching between two alternative pairing interactions (Breaker, 2011).

One of the most extensively characterized aptamers is a simple motif that binds adenosine. The aptamer was first identified in an in vitro selection for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding RNAs (Sassanfar and Szostak, 1993), and later in several independent selection experiments targeting adenosine-containing cofactors, including nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (Burgstaller and Famulok, 1994), S-adenosyl methionine (Burke and Gold, 1997), and S-adenosylhomocysteine (Gebhardt et al., 2000). The aptamer recognizes adenosine and its 5′ phosphorylated analogs by an 11-nt loop and a bulged guanosine located on the opposite strand. Solution structures of AMP-bound complexes revealed that the conserved recognition loop folds into a compact binding site that contacts the Watson-Crick face of the nucleobase and the 2′ position of the ribose (Dieckmann et al., 1997; Dieckmann et al., 1996; Jiang et al., 1996), explaining the binding specificity for adenine ribonucleoside and tolerance to substitutions at the 8 and 5′ positions (Sassanfar and Szostak, 1993). The reproducible isolation of this motif from random sequences suggests that it is the simplest adenosine binding structure, providing a striking example of convergent molecular evolution. Despite this structural convergence in vitro, the aptamer has not been identified in genomic sequences, therefore it has not been known whether the convergence extends to biological systems and whether biological ligand-binding RNAs, particularly riboswitches, utilize this motif for regulatory or other functions.

Riboswitches are functional RNAs composed of aptamer domains and expression platforms, which bind molecular targets and regulate gene expression, respectively (Breaker, 2011). Most riboswitches have been found in bacteria, with a single example described in algae, fungi, and plants, but not other eukaryotes (Cheah et al., 2007; Croft et al., 2007; Kubodera et al., 2003; Wachter et al., 2007). The aptamer domains of the riboswitches comprise a diverse set of RNA structures, ranging from three-way junctions to intricate pseudoknots (Montange and Batey, 2008); however, these motifs are different from in vitro selected aptamers targeting the same ligands. This observation suggests that in vitro selected and biological aptamer domains follow separate evolutionary pathways, perhaps because in vitro evolved aptamers are optimized for target binding and efficiency of amplification during the selection process, whereas the riboswitch motifs have evolved to couple target binding to gene expression regulation. On the other hand, the methods used to identify the aptamer domains in synthetic and biological sequences are distinct, relying on in vitro selection and phylogenetic conservation of the aptamer structure, respectively, and may thus bias the identified motifs. Moreover, in vitro selected aptamers are typically smaller than riboswitches, in part because the length of the starting selection pool tends to be shorter than the typical riboswitch. In principle, however, the motifs recognizing the same ligand can be isolated from random sequences and identified in genomic sequences, especially if the methods used are amenable to the discovery of simple RNA motifs that may be abundant in both sequence sets.

To test whether in vitro identified aptamer motifs exist in genomic sequences, we used structure-based searches (Riccitelli and Lupták, 2010) and identified adenosine aptamers in a bacterium and several vertebrates, including humans. Furthermore, to identify all adenosine-binding RNAs encoded in the human genome, independent of structure, we performed an in vitro selection for ATP-binding transcripts of a human genomic pool (Salehi-Ashtiani et al., 2006) and discovered two more aptamers. Surprisingly, both aptamers fold into the same structure as was identified in vitro. Two of the three human aptamers map to introns of expressed genes and may sense ATP concentration through a kinetic mechanism.

RESULTS

Structure-based Search for Genomic Adenosine Aptamers

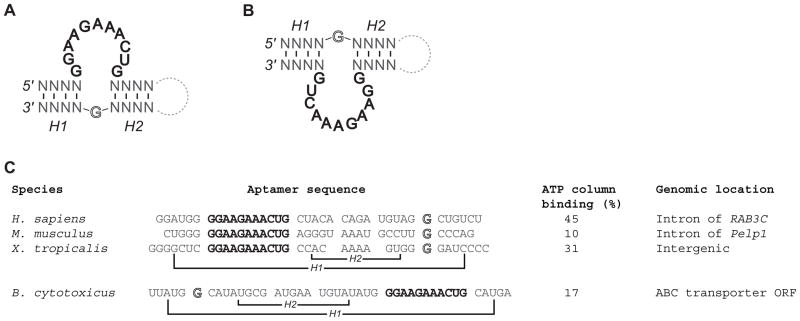

We performed the motif searches by designing a descriptor for the adenosine aptamer structure, based on the known sequence variants and solution structures (Burgstaller and Famulok, 1994; Burke and Gold, 1997; Dieckmann et al., 1997; Dieckmann et al., 1996; Gebhardt et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 1996; Sassanfar and Szostak, 1993). The aptamers recognize any adenosine-containing molecule with exposed ribose and adenine moieties using a conserved 11-nt loop opposite to a single guanosine and flanked by two helical segments (Fig. 1A and 1B). Because of its asymmetry, the adenosine-binding loop can be incorporated into the flanking sequences through either of two topologies, with the loop in either the 5′ or the 3′ strand of the aptamer, requiring two separate descriptors (Riccitelli and Lupták, 2010). Both topologies have been identified among in vitro selected sequences, with a slight preference for the loop in the 5′ strand (Burke and Gold, 1997; Sassanfar and Szostak, 1993), thus we designed descriptors for both orientations. Whereas the aptamer fold is simple, its information content (≥35 bits (Carothers et al., 2006)) suggests that it should appear by chance no more than about once per ten mammalian genomes and it should be readily isolated from random libraries of diversities >5e10, as confirmed by several independent experiments (Burgstaller and Famulok, 1994; Burke and Gold, 1997; Gebhardt et al., 2000; Sassanfar and Szostak, 1993). We threaded the publicly available reference genomes through the structure descriptors and identified sequences capable of assuming the same fold. Our search revealed a number of potential aptamers, but very few that perfectly matched the consensus structure identified in vitro. Most candidate aptamers had weaker paired regions or mutations in the binding loop, suggesting that they have lower affinity for adenosine than the optimal in vitro selected aptamers (KD~1 μM).

Fig. 1.

Genomic adenosine aptamers uncovered using structure-based bioinformatics. Secondary structure descriptors for the in vitro selected adenosine aptamer, with the recognition loop (shown in bold) in the 5′ strand (A) or the 3′ strand (B). Both topologies have been identified in vitro (Burgstaller and Famulok, 1994; Sassanfar and Szostak, 1993). The bulged guanosine required for ligand binding is outlined on a strand opposite of the recognition loop. (C) Sequences of aptamers that showed robust ATP binding in vitro. Fraction of each RNA eluted from ATP-agarose beads in the presence of 5 mM ATP-Mg and genomic locations of the aptamers are listed on the right. Outer and inner helices of the structure are marked as H1 and H2, respectively. The B. cytotoxicus sequence has the recognition loop in the 3′ segment of the aptamer.

In Vitro Activity of Aptamer Candidates

To test their in vitro activity, we transcribed the putative aptamers from synthetic templates corresponding to the genomic sequences, purified, and incubated with ATP-agarose beads at conditions similar to the ones used for in vitro selections (Sassanfar and Szostak, 1993). After extensive washing, the aptamers were eluted with 5 mM AMP or ATP-Mg and the fraction of specifically bound RNA was determined using scintillation counting. Several RNAs showed significant ATP binding and competitive elution, including sequences mapping to genomes of a bacterium and several vertebrates: Bacillus cytotoxicus, western clawed frog, mouse, marmoset, chimp, and human (Fig. 1C; the primate aptamers are almost identical and their alignment is shown in Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Human RAB3C adenosine aptamer discovered using structure-based bioinformatics. (A) Mapping of the aptamer sequence onto the primate RAB3C gene. (B) Sequence alignment of the primate RAB3C aptamers, with the adenosine-binding loop underlined in red. The marmoset and chimp sequences have activity similar to the human sequence (data not shown). (C) Predicted secondary structure of the RAB3C aptamer, with the ligand-binding loop shown in red. Red and blue brackets indicate positions used to detect ligand binding and in-line probing reference bands, respectively, shown in (E). 5′ guanosine was introduced to facilitate in vitro transcription and is not present in the genomic sequences. (D) Binding of ATP column and elution with AMP (FT, flow-through; C, fraction of RNA bound to the column after three AMP elution steps). (E) In-line probing (Soukup and Breaker, 1999) of the 3′-labeled aptamer at physiological-like conditions in the presence of AMP. The band intensities that change with AMP concentration correspond to the predicted binding loop positions, confirming the predicted secondary structure. The sequence of the RNA was determined using iodoethanol cleavage of aptamers with phosphorothioate-modified backbone at positions indicated above each lane. The aptamer shows a single-nucleotide heterogeneity at its 3′ end, resulting in doublets for all positions. (F) Binding of the aptamer to ATP (▲), AMP (△), dATP (▲), and GTP (●) based on in-line probing experiments and fit using a single binding site model (see Fig. S1 for probing in the presence of ATP, dATP, and GTP). The dissociation constants for ATP and AMP are ~400 μM and ~200 μM, respectively. Gray area corresponds to the concentration range of ATP in human tissues (Buchli et al., 1994; Kemp et al., 2007).

The bacterial aptamer resides in a gene coding for an ABC transporter, an ATP-binding permease protein. The aptamer bound to an ATP column, and eluted specifically in the presence of free ATP or AMP (data not shown). The sequence was unique to B. cytotoxicus (NVH391-98); other Bacillus species carry mutations in both the adenosine recognition loop and the flanking helices. While these mutations do not individually abrogate ligand binding (Dieckmann et al., 1997), their combination resulted in complete loss of affinity for ATP-agarose, suggesting that the aptamer is not a conserved regulatory element among Bacillus species, but rather represents a possible gain-of-function variant of a diverged B. cereus species (Lapidus et al., 2008).

The aptamers found in the frog (Xenopus tropicalis) and mouse (Mus musculus) genomes also showed robust binding to ATP-agarose column and elution in presence of free ATP (data not shown). The frog aptamer maps to an intergenic region and the mouse aptamer maps antisense to a MIRc SINE element in an intron of the Pelp1 gene, which codes for an estrogen receptor coregulator. The distance from the end of the aptamer to the next exon of the Pelp1 gene is only 88 nts, suggesting that the aptamer may influence the splicing of the exon, but the sequence is not conserved among rodents, therefore it is unlikely it has a broad biological role.

Characterization of the Human RAB3C Aptamer

The primate aptamer maps to the last intron of the RAB3C gene (Fig. 2A and 2B), which codes for a GTPase involved in regulation of exocytosis (Schonn et al., 2010). The human sequence bound an ATP column and eluted with AMP (Fig. 2D), but not with GMP. Mutation of the “opposing” guanosine of the recognition loop to adenosine abolished ATP binding, as was shown previously for the in vitro selected aptamers (Dieckmann et al., 1996). Partial hydrolysis of the RNA under physiological-like conditions (37 °C, 140 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM tris-HCl or 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.9, 1 mM spermidine, 1 mM MgCl2), also known as in-line probing, showed significant adenosine-dependent changes in the canonical adenosine recognition loop (Soukup and Breaker, 1999) (Fig. 2E). The apparent dissociation constants (KDs) calculated from the characteristic increase of degradation in the middle of the binding loop were ~200 μM and ~400 μM for AMP and ATP, respectively (Fig. 2F). No change in the degradation pattern was observed in the presence of 2′-dATP or GTP, confirming that the aptamer is specific for adenosine (Fig. S1).

In Vitro Selection of Human Adenosine Aptamers

The discovery of a robust human adenosine aptamer led us to consider two questions: 1) how many human aptamers exist and 2) do human adenosine aptamers form multiple structural families? To measure the distribution of all ATP aptamers in the human genome, independent of structure or cellular expression, we performed an in vitro selection experiment from an ~150-nt human genomic library (Salehi-Ashtiani et al., 2006). We carried out the selection essentially as described before (Sassanfar and Szostak, 1993), binding the pool of transcripts to ATP-agarose beads and eluting the bound fraction with ATP-Mg at physiological-like salt conditions described above. This unbiased approach yielded another two aptamers: one that maps antisense to a junction between an ERV1 LTR repeat and its 3′ insertion site, and another that resides in an intron of the FGD3 gene (Fig. 3), which codes for a guanyl nucleotide exchange factor regulating cell morphology and motility (Hayakawa et al., 2008). Surprisingly, both of these sequences were predicted to fold into the canonical structure found in the RAB3C and in vitro selected adenosine aptamers. ATP column binding and “in-line” probing experiments of individual selection clones showed robust binding to ATP by the predicted recognition loop (KD~130 μM) (Fig. S2). The aptamer found straddling the ERV1 insertion site was not identified at other ERV1 insertion sites, suggesting that the ability to bind adenosine is not generally associated with antisense transcripts of the ERV1 and that this instance potentially represents a unique gain of function facilitated by a mobile genetic element.

Fig. 3.

In vitro selected human FGD3 adenosine aptamer. (A) Mapping of the aptamer to the FGD3 intron. (B) Aptamer sequence conservation among primates. Red bars indicate positions that form the adenosine-binding loop. (C) Secondary structure of the aptamer based on in-line probing and thermodynamic structure predictions. (D) Co-transcriptional binding of ATP-agarose beads and competitive elution with ATP-Mg under physiological-like conditions. See Fig. S2 for the secondary structure of the clone sequence, full alignment of primate sequences, and in-line data with ATP.

Co-transcriptional Binding of ATP by the Human FGD3 Aptamer

Because the FGD3 aptamer clones included the primer binding sites introduced during the construction of the genomic library, we also tested genomic sequences lacking these artificial sequences. Even though the predicted secondary structure suggested that the adenosine aptamer fold forms in absence of the primer sequences, none of the genomic constructs bound ATP under equilibrium conditions, when a purified RNA was incubated with either ATP beads or free ATP. The predicted secondary structure included potential alternative folds, suggesting that the lowest energy of the adenosine-free RNA may prevent formation of the adenosine-binding loop. We reasoned that while the RNA had the ability to form the binding loop, as evidenced by the in vitro selected clone, once purified using denaturing gel electrophoresis, the aptamer likely folded into a non-binding conformation. However, given that some riboswitches control gene expression kinetically, sensing ligand concentrations during transcription in order to promote termination shortly after the synthesis of the aptamer domains (Wickiser et al., 2005), we hypothesized that the adenosine-binding conformation of the FGD3 aptamer could form transiently during transcription. To test this hypothesis, we incubated the in vitro transcription reaction in the presence of ATP beads, and measured the fraction of the newly transcribed RNA that bound the beads and dissociated in the presence of free ATP. Under these conditions, a significant fraction of the aptamers bound ATP-agarose specifically (in the presence of 500 μM free ATP used for transcription) (Fig. 3D). This result suggested that the FGD3 aptamer may sense cellular ATP using a kinetic mechanism, although any biological role for this RNA remains to be elucidated.

DISCUSSION

To date, most riboswitches have been identified in bacteria (Breaker, 2011), typically regulating transcription termination or translation initiation, and a single example has been described in algae, fungi, and plants, where the thiamine pyrophosphate riboswitch regulates alternative splicing or mRNA processing (Cheah et al., 2007; Croft et al., 2007; Kubodera et al., 2003; Wachter et al., 2007). Given the broad distribution of bacterial riboswitches, the paucity of eukaryotic examples is surprising, and perhaps reflects the need for novel computational and experimental tools for their discovery. Structure-based searches for known aptamer motifs and direct in vitro selection of ligand binding RNAs used in this study show that both approaches yield new eukaryotic ligand-binding RNAs, although their regulatory function has yet to be demonstrated. The association of two of the vertebrate aptamers with retrotransposons also indicates that the evolution of functional RNAs in eukaryotic genomes may be strongly coupled to the activity of mobile genetic elements, potentially extending their gene regulatory functions to include eukaryotic riboswitches.

Our results show that a bacterium and several vertebrates harbor adenosine aptamers of the same structural family as have been discovered using in vitro selections, demonstrating that the convergent molecular evolution of adenosine binding encompasses genomic sequences. In vitro selection from a human genomic library revealed the same structural family, indicating that the convergent evolution of adenosine-binding RNAs extends to all human genomic aptamers. Previous studies identified several synthetic aptamers and biological riboswitches that bind the same ligand (e.g. adenine, flavin mononucleotide, S-adenosyl homocysteine) (Burgstaller and Famulok, 1994; Gebhardt et al., 2000; Mandal and Breaker, 2004; Meli et al., 2002; Mironov et al., 2002; Weinberg et al., 2010; Winkler et al., 2002), but adenosine is the only ligand for which the same aptamer motif has been identified in both random pools and genomes. The convergent molecular evolution spanning synthetic and genomic sequences thus mirrors that of another simple functional RNA, the hammerhead self-cleaving ribozyme (Hammann et al., 2012; Salehi-Ashtiani and Szostak, 2001).

The biological functions of the adenosine aptamers remain unknown. Our data suggest that the primate RAB3C and FGD3 aptamers may sense the ATP concentration using a kinetic mechanism. In the case of the FGD3 aptamer, we detected ATP binding only during transcription and not in equilibrium experiments, supporting the hypothesis that the genomic sequence assumes ATP-binding conformation only transiently and any biological function associated with the aptamer would have to be coupled to the co-transcriptional binding. The RAB3C aptamer KD for ATP is about an order of magnitude below the concentration of ATP, which at 2 to 9 mM is the most concentrated adenosine-containing small molecule in human tissues (Buchli et al., 1994; Kemp et al., 2007). Thus, under equilibrium conditions and normal ATP levels, the aptamer binding sites would be nearly saturated; however, if the cellular ATP concentration decreased about ten-times, a significant fraction of the aptamers would remain unoccupied. If the aptamer domain is connected to a regulatory process, it may be used to sense a large change in ATP concentration. Alternatively, if the aptamer is coupled to a co-transcriptional regulatory process, it may sense changes in ATP concentrations through a kinetic mechanism, whereby the occupancy of the aptamer domain would be proportional to the rate at which the ligand binds (Garst et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2010). A change of ATP concentration within the normal physiological range of 2–9 mM would lead to almost a five-fold range of binding rates, and the range would be even greater if the ATP concentration deviates significantly from the normal levels. Thus any process kinetically coupled to the rate of binding by ATP could be sensed by this aptamer. Further experiments will be necessary to establish what, if any, biological processes these aptamers affect.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Structure-based searches

We used the RNABOB program (courtesy of S. Eddy, HHMI; ftp://selab.janelia.org/pub/software/rnabob/), to perform motif searches (Riccitelli and Lupták, 2010). The secondary structure of the adenosine aptamer was based on in vitro selected RNAs that bind adenosine-containing molecules: adenosine triphosphate (Sassanfar and Szostak, 1993), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (Burgstaller and Famulok, 1994), S-adenosyl methionine (Burke and Gold, 1997), and S-adenosylhomocysteine (Gebhardt et al., 2000). In addition, we incorporated constraints based on the solution structures of the AMP-bound aptamers (Dieckmann et al., 1997; Dieckmann et al., 1996; Jiang et al., 1996). The secondary structure was divided into the recognition loops (s1 and s3) flanked by single strict base-pairs (r2 and r3 elements). The rest of the helices were allowed to contain G•U wobble pairs (h1 and h4 elements). The following are descriptors for aptamers with the recognition loop in the 5′ (#1) and 3′ (#2) strands corresponding to the circularly permuted motif:

#1 h1 r2 s1 r3 h4 s2 h4′ r3′ s3 r2′ h1′ h1 0:0 NNNN:NNNN r2 0:0 N:N TGCA s1 0 GGAAGAAMCUG r3 0:0 N:N TGCA h4 0:0 NNNN:NNNN s2 0 NNN[10] s3 0 G

#2 h1 r2 s1 r3 h4 s2 h4′ r3′ s3 r2′ h1′ h1 0:0 NNNN:NNNN r2 0:0 N:N TGCA s1 0 G r3 0:0 N:N TGCA h4 0:0 NNNN:NNNN s2 0 NNN[10] s3 0 GGAAGAAMCUG

RNA Transcription

RNA was transcribed at 37 °C for one to three hours in a volume of 20 μL containing 40 mM tris chloride, 10 % dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 10 mM DTT, 2 mM spermidine, 2.5 mM each CTP, GTP, and UTP, 250 μM ATP, 2.25 μCi [α-32P]-ATP (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA), 25 mM MgCl2 one unit of T7 RNA polymerase, and 0.2 μM of DNA template. DMSO was used to increase transcript yields, as documented in previous studies (Chen and Zhang, 2005). The transcripts were purified using denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

3prime;-terminus Labeling

RNA ligation reactions were performed essentially as previously described (England et al., 1980). Briefly, RNA transcribed in the absence of [α-32P]-ATP was PAGE-purified and ligated at 37 °C for three hours in a volume of 10 μL, containing RNA Ligase Buffer (NEB), 2 μCi [5′-32P] cytidine 3′, 5′-bisphosphate (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA) and one unit of T4 RNA ligase (NEB) and PAGE-purified again.

In-line Probing

In-line probing reactions were performed as previously described (Regulski and Breaker, 2008; Soukup and Breaker, 1999). The 3′-end labeled RNA was incubated with varying amounts of ligand for one or two days at 37 °C in a buffer containing 140 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.9 or tris chloride pH 7.9, 1 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM spermidine. Triphosphorylated ligands (ATP, dATP, GTP) were prepared as 1:1 complexes with Mg2+. AMP was used directly, without additional divalent metal ions. The partially hydrolyzed RNAs were resolved using denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, exposed to phosphorimage screens (Molecular Dynamics) and scanned by GE Typhoon phosphorimager. The band intensities were analyzed by creating line profiles of each lane using ImageJ, exporting the graphs into IgorPro, and fitting all peaks by Gaussian curves. The areas of the fitted curves were used to measure intensity changes of the binding loop and divided by intensities of a control band. The resulting ratios were plotted in Excel as a function of ligand concentration and modeled with a dissociation constant equation for a single ligand:

The model was fit to the data using a linear least-squares analysis and the Solver module of Microsoft Excel.

Sequence of the adenosine-binding loop were confirmed by running iodoethanol-cleaved RNAs with α-phosphorothioate nucleotides incorporated at indicated positions (Gish and Eckstein, 1988; Ryder and Strobel, 1999). The dominant product of phosphorothioate sequencing, a 2′-3′ cyclic phosphate, is the same as in in-line probing (Soukup and Breaker, 1999), allowing a direct readout of the positions affected by the bound ligand.

In vitro Selection

The DNA pool used for the in vitro selection was derived from the human genome and described previously (Salehi-Ashtiani et al., 2006). Purified RNA transcripts were precipitated, dried, and resuspended in 200 μl binding buffer containing 140 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM tris chloride pH 7.5, and 5 mM MgCl2 and heated to 70 °C before loading onto C8-linked ATP agarose beads (Sigma) equilibrated in the binding buffer. Flow-through was collected after the columns were capped and shaken for 20 minutes at room temp. The beads were washed with 200 μl of binding buffer, and potential aptamers eluted with the same buffer supplemented by 5 mM ATP•Mg with 30 minutes of shaking at room temperature. Each fraction was analyzed for radioactivity using a liquid scintillation counter. Elutions were pooled, desalted using YM-10 spin filters (Millipore), precipitated, dried, and resuspended in H2O.

In vitro selection primers

Forward: 5′ GATCTGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCAGACGTGCCTCACTAC 3′ Reverse: 5′ CTGAGCTTGACGCATTG 3′

Reverse transcription

RNA was reverse transcribed in 20 μl using the Promega reverse transcription buffer, 2 μM reverse primer and RNA recovered from the previous selection round. The RNA and primer were annealed by heating at 65 °C and cooling to room temperature before 1 unit of Thermoscript (Invitrogen) and Improm II (Promega) reverse transcriptases each were added. The reaction was initiated for 5 minutes at 25 °C and then the temperature was ramped to 42 °C, 50 °C, 55 °C, and 65 °C for 15 minutes each before the enzymes were inactivated at 85 °C for 5 minutes.

Amplification

DNA was amplified by using DreamTaq Master Mix (Fermentas), 2 μM forward primer, 2 μM reverse primer, and DNA from reverse transcription. DNA was initially denatured at 95 °C for 1.5 minutes (30 sec for subsequent denaturing steps), annealed at 55 °C for 30 sec, and extended at 72 °C for each cycle. Optimum number of PCR cycles was determined for each selection round by comparing 8,12,16, and 20 cycle aliquots on agarose gel.

Cloning

After five rounds of selection the pool was cloned using the Topo TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) and individual colonies were directly PCR-amplified and sequenced. Only two unique sequences, the FGD3 and ERV1, were found:

FDG3 (chr9:95,787,061-95,787,193)

GGTCCTGG GGAGTCTAAC CCCCGGGTTG GTGCCCTGAC AGGAGgATGT TCTtGCTGGA AGAACCTGCA AGGCCATTGT TTAAgATGTT TTAACTTGTG GGAAGACACA GCTTGGAGAT GGCCTTGGAG

ERV1 (chr3:162359023-162359154)

AGAAGC AAGAAGGAAG AAAcTGCCAc CGTTGTCATC TTGTGTCTGa AATTGGTGGn TTCTTGGTCT CACTGgCTTC AAGAATGAAG CCGTGGACCC TCGCGGTGAG TGTTACAGTT CTTAAAGGCG GTGTCT

Lower-case letters are mutations acquired during the in vitro selection or library construction, as compared with the reference genome. The putative adenosine-binding loop is highlighted in bold. The ERV1 aptamer contained an A-to-C mutation in the recognition loop (underlined) in all sequenced clones. The genomic sequence is likely to bind adenosine, because this variant has been observed among in vitro selected clones (Sassanfar and Szostak, 1993). As with the other two aptamers, in-line probing showed an ATP-dependent change in the hydrolysis pattern for the predicted loop characteristic of this class of aptamers (Soukup and Breaker, 1999), confirming that the cloned sequence forms the same binding loop.

Co-transcriptional binding assay

RNA was transcribed in a Spin-X column (Corning) for 30 min at 37 °C in 50 μl solution containing 40 mM tris chloride, 10 % DMSO, 10 mM of DTT, 5 mM each GTP, UTP and CTP, 500 μM ATP, 3.75 μCi [α-32P]-ATP (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA), 25 mM MgCl2, 1 unit of T7 RNA polymerase, 50 pmole of DNA template and C8 linked ATP agarose beads washed and equilibrated in transcription buffer. The columns were centrifuged at 4,000 g for 1 minute and flow-through collected. The columns were washed in 50 μl of the binding buffer and centrifuged. Elutions were collected in the ATP•Mg elution buffer following 30 minutes of shaking. Each fraction was resolved on a denaturing PAGE gel to separate the full-length transcripts from unincorporated [α-32P]-ATP and shorter transcripts. The gels were exposed to phosphor image plate, scanned, and the amount of full-length RNAs measured with ImageJ software.

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE.

Aptamers are structured macromolecules in vitro evolved to bind a variety of molecular targets. In biological systems aptamers form the ligand-binding domains of riboswitches – cofactor-dependent cis regulatory RNAs. The ligand-binding motifs identified in vitro and in riboswitches are diverse, even for the same ligand, suggesting that synthetic and biological aptamers follow separate evolutionary paths to achieve high binding specificity and affinity. A paradigm of convergent molecular evolution among aptamers is represented by the adenosine-binding motif, which was identified in several independent in vitro experiments, but had not been previously found in genomic sequences. We used structure-based bioinformatics to measure the distribution of these aptamers in genomes and discovered that they map to organisms spanning from bacteria to humans. The human aptamer is conserved among primates, maps to an intron of the RAB3C gene, and binds ATP with dissociation constant about ten times lower than physiological ATP concentration. Further, to experimentally measure the distribution of all human adenosine-binding aptamers, independent of structure, we performed an in vitro selection from a genomic library and isolated two more aptamers. Both sequences fold into the same structure as was identified in random sequences and the RAB3C gene, demonstrating that its structural convergence extends to all human adenosine aptamers. One of the aptamers maps to an intron of the FGD3 gene and exhibits full sequence conservation among primates, but the genomic construct binds ATP exclusively co-transcriptionally and not in equilibrium experiments. The human adenosine aptamers may be kinetically controlled ATP sensors.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Adenosine aptamers are paradigms of convergent molecular evolution

Structure-based search revealed this motif in bacterial and vertebrate genomes

In vitro selection from a human genomic library yielded two more aptamers

One of the human aptamers binds ATP exclusively co-transcriptionally

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the University of California, Irvine and the Pew Charitable Trusts (A.L.), UCI SURP (M.M.K.V. & D.L.), NSF IGERT (N.E.J.), and NIH Post-Baccalaureate Research Education Program (S.J.M.). We thank S. Chen for initiation of the in vitro selection experiment. A.L. is a member of the Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Institute of Genomics and Bioinformatics at UC Irvine.

Footnotes

Author Contributions. R.L.-R. and A.L. designed the experiments. S.J.M., R.L.-R. and A.L. performed the structure-based searches. N.E.J., S.J.M. and D.L. performed the biochemical analysis of aptamer candidates. M.M.K.V. performed the in vitro selection and biochemical analysis of the clones. All authors analyzed the data and A.L. wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Information includes two figures and can be found in this article online at doi: ….

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Breaker RR. Prospects for riboswitch discovery and analysis. Mol Cell. 2011;43:867–879. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchli R, Meier D, Martin E, Boesiger P. Assessment of absolute metabolite concentrations in human tissue by 31P MRS in vivo. Part II: Muscle, liver, kidney. Magn Reson Med. 1994;32:453–458. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgstaller P, Famulok M. Isolation of RNA Aptamers for Biological Cofactors by in-Vitro Selection. Angew Chem Int Edit. 1994;33:1084–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Burke DH, Gold L. RNA aptamers to the adenosine moiety of S-adenosyl methionine: structural inferences from variations on a theme and the reproducibility of SELEX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2020–2024. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.10.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carothers JM, Davis JH, Chou JJ, Szostak JW. Solution structure of an informationally complex high-affinity RNA aptamer to GTP. RNA. 2006;12:567–579. doi: 10.1261/rna.2251306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah MT, Wachter A, Sudarsan N, Breaker RR. Control of alternative RNA splicing and gene expression by eukaryotic riboswitches. Nature. 2007;447:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nature05769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Zhang Y. Dimethyl sulfoxide targets phage RNA polymerases to promote transcription. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:664–670. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft MT, Moulin M, Webb ME, Smith AG. Thiamine biosynthesis in algae is regulated by riboswitches. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20770–20775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705786105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann T, Butcher SE, Sassanfar M, Szostak JW, Feigon J. Mutant ATP-binding RNA aptamers reveal the structural basis for ligand binding. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:467–478. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann T, Suzuki E, Nakamura GK, Feigon J. Solution structure of an ATP-binding RNA aptamer reveals a novel fold. RNA. 1996;2:628–640. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington AD, Szostak JW. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature. 1990;346:818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England TE, Bruce AG, Uhlenbeck OC. Specific labeling of 3′ termini of RNA with T4 RNA ligase. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65:65–74. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garst AD, Edwards AL, Batey RT. Riboswitches: structures and mechanisms. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt K, Shokraei A, Babaie E, Lindqvist BH. RNA aptamers to S-adenosylhomocysteine: kinetic properties, divalent cation dependency, and comparison with anti-S-adenosylhomocysteine antibody. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7255–7265. doi: 10.1021/bi000295t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gish G, Eckstein F. DNA and RNA Sequence Determination Based on Phophorothioate Chemistry. Science. 1988;240:1520–1522. doi: 10.1126/science.2453926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammann C, Luptak A, Perreault J, de la Pena M. The ubiquitous hammerhead ribozyme. RNA. 2012;18:871–885. doi: 10.1261/rna.031401.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa M, Matsushima M, Hagiwara H, Oshima T, Fujino T, Ando K, Kikugawa K, Tanaka H, Miyazawa K, Kitagawa M. Novel insights into FGD3, a putative GEF for Cdc42, that undergoes SCF(FWD1/beta-TrCP)-mediated proteasomal degradation analogous to that of its homologue FGD1 but regulates cell morphology and motility differently from FGD1. Genes Cells. 2008;13:329–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Kumar RA, Jones RA, Patel DJ. Structural basis of RNA folding and recognition in an AMP-RNA aptamer complex. Nature. 1996;382:183–186. doi: 10.1038/382183a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp GJ, Meyerspeer M, Moser E. Absolute quantification of phosphorus metabolite concentrations in human muscle in vivo by P-31 MRS: a quantitative review. Nmr Biomed. 2007;20:555–565. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubodera T, Watanabe M, Yoshiuchi K, Yamashita N, Nishimura A, Nakai S, Gomi K, Hanamoto H. Thiamine-regulated gene expression of Aspergillus oryzae thiA requires splicing of the intron containing a riboswitch-like domain in the 5′-UTR. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:516–520. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01335-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapidus A, Goltsman E, Auger S, Galleron N, Segurens B, Dossat C, Land ML, Broussolle V, Brillard J, Guinebretiere MH, et al. Extending the Bacillus cereus group genomics to putative food-borne pathogens of different toxicity. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;171:236–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal M, Breaker RR. Adenine riboswitches and gene activation by disruption of a transcription terminator. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:29–35. doi: 10.1038/nsmb710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meli M, Vergne J, Decout JL, Maurel MC. Adenine-aptamer complexes: a bipartite RNA site that binds the adenine nucleic base. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:2104–2111. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironov AS, Gusarov I, Rafikov R, Lopez LE, Shatalin K, Kreneva RA, Perumov DA, Nudler E. Sensing small molecules by nascent RNA: A mechanism to control transcription in bacteria. Cell. 2002;111:747–756. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01134-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montange RK, Batey RT. Riboswitches: emerging themes in RNA structure and function. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:117–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.130000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regulski EE, Breaker RR. In-line probing analysis of riboswitches. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;419:53–67. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-033-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccitelli NJ, Lupták A. Computational discovery of folded RNA domains in genomes and in vitro selected libraries. Methods. 2010;52:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder SP, Strobel SA. Nucleotide analog interference mapping. Methods. 1999;18:38–50. doi: 10.1006/meth.1999.0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi-Ashtiani K, Lupták A, Litovchick A, Szostak JW. A genomewide search for ribozymes reveals an HDV-like sequence in the human CPEB3 gene. Science. 2006;313:1788–1792. doi: 10.1126/science.1129308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi-Ashtiani K, Szostak JW. In vitro evolution suggests multiple origins for the hammerhead ribozyme. Nature. 2001;414:82–84. doi: 10.1038/35102081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassanfar M, Szostak JW. An RNA motif that binds ATP. Nature. 1993;364:550–553. doi: 10.1038/364550a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonn JS, van Weering JR, Mohrmann R, Schluter OM, Sudhof TC, de Wit H, Verhage M, Sorensen JB. Rab3 proteins involved in vesicle biogenesis and priming in embryonic mouse chromaffin cells. Traffic. 2010;11:1415–1428. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukup GA, Breaker RR. Relationship between internucleotide linkage geometry and the stability of RNA. RNA. 1999;5:1308–1325. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenburg R, Reinemann C, Strehlitz B. SELEX--a (r)evolutionary method to generate high-affinity nucleic acid ligands. Biomol Eng. 2007;24:381–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuerk C, Gold L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science. 1990;249:505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachter A, Tunc-Ozdemir M, Grove BC, Green PJ, Shintani DK, Breaker RR. Riboswitch control of gene expression in plants by splicing and alternative 3′ end processing of mRNAs. Plant Cell. 2007;19:3437–3450. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg Z, Wang JX, Bogue J, Yang J, Corbino K, Moy RH, Breaker RR. Comparative genomics reveals 104 candidate structured RNAs from bacteria, archaea, and their metagenomes. Genome biology. 2010;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickiser JK, Winkler WC, Breaker RR, Crothers DM. The speed of RNA transcription and metabolite binding kinetics operate an FMN riboswitch. Mol Cell. 2005;18:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler WC, Cohen-Chalamish S, Breaker RR. An mRNA structure that controls gene expression by binding FMN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15908–15913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212628899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Lau MW, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. Ribozymes and riboswitches: modulation of RNA function by small molecules. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9123–9131. doi: 10.1021/bi1012645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.