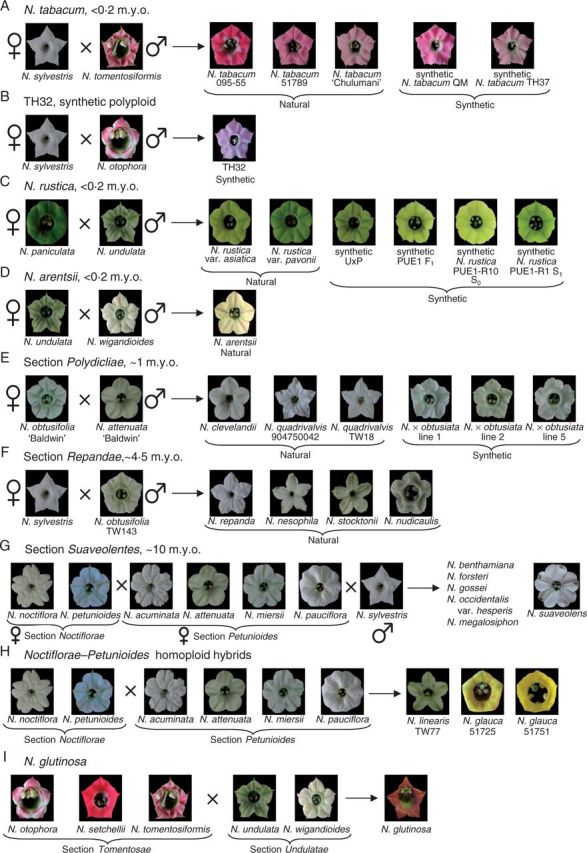

Fig. 1.

Floral colour, as perceived by humans, of polyploid and homoploid hybrid Nicotiana and their diploid progenitors. Polyploid ages were estimated using a molecular clock calibrated with the geological age of volcanic islands with endemic Nicotiana species (Clarkson et al., 2005). Absolute dates (millions of years, m.y.o.) estimated by the clock should be treated with caution; however, relative ages of different polyploid sections should reflect the true sequence of polyploidization events. (A) Natural and synthetic polyploids of N. tabacum. (B) Synthetic polyploid TH32. (C) Natural and synthetic N. rustica polyploids. Synthetic hybrids include a homoploid from a reciprocal cross and a polyploid series (F1 homoploid and S0 and S1 polyploids) of the same parentage as natural N. rustica. (D) Nicotiana arentsii. (E) Natural polyploids of section Polydicliae. Synthetic N. × obtusiata polyploid lines were made from a cross between the N. obtusifolia and N. attenuata accessions studied here. (F) Section Repandae. (G) Section Suaveolentes contains 26 polyploid species (six included in this study). Biogeographical analyses suggest that section Suaveolentes originated ∼15 million years ago (m.y.a.), before the aridification of Australia (Ladiges et al., 2011), and this seems to be relatively congruent with the molecular clock results, which place its origin at ∼10 m.y.a. (H) Homoploid hybrids N. glauca and N. linearis. (I) Homoploid hybrid N. glutinosa. Photographs are scaled to the same size.