Abstract

The paper presents the principles of performing proper ultrasound examinations of the urinary tract. The following are discussed: preparation of patients, type of optimal apparatus, technique of examination and conditions which its description should fulfill. Urinary track examination in adults and in children constitutes an integral part of each abdominal examination. Such examinations should be performed with fasting patients or several hours after the last meal, with filled urinary bladder.

Apparatus

Ultrasound examinations in children and infants are performed using transducers with the frequency of 5.0–9.0 MHz and in adults – with the frequency of 2.0–6.0 MHz. Doppler options are desirable since they improve diagnostic capacity of sonography in terms of differentiation between renal focal lesions.

Scanning technique

Renal examinations are performed with the patients in the supine position. The right kidney is examined in the right hypochondriac region using the liver as the ultrasound “window.” The left kidney is examined in the left hypochondriac region, preferably in the posterior axillary line. Ultrasound examinations of the upper segment of the ureters are performed after renal examination when the pelvicalyceal system is dilated. A condition necessary for a proper examination of the perivesical portion of the ureter is full urinary bladder. The scans of the urinary bladder are performed in transverse, longitudinal and oblique planes when the bladder is filled.

Description of the examination

The description should include patient's personal details, details of the referring unit, of the unit in which the examination is performed, examining physician's details, type of ultrasound apparatus and transducers as well as the description proper.

Keywords: ultrasound imaging of the urinary system, renal ultrasound examination, ultrasound examination of the ureters, ultrasound examination of the urinary bladder

Abstract

Przedstawiono zasady prawidłowego wykonania badania ultrasonograficznego układu moczowego. Uwzględniono przygotowanie chorego, rodzaj optymalnego ultrasonografu, przedstawiono technikę badania oraz warunki, jakie powinien spełniać jego opis. Badanie układu moczowego u dorosłych i u dzieci stanowi integralną część każdego badania jamy brzusznej. Badanie powinno być wykonane na czczo lub kilka godzin po posiłku, z wypełnionym pęcherzem moczowym.

Aparatura

Badania u dzieci i niemowląt wykonuje się głowicami o częstotliwości 5,0–9,0 MHz, a u dorosłych o częstotliwości 2,0–6,0 MHz, najlepiej z możliwością badań dopplerowskich. Wykonanie badań dopplerowskich zwiększa możliwości diagnostyczne w różnicowaniu zmian ogniskowych nerek.

Technika badania

Badanie nerek wykonywane jest w pozycji leżącej na plecach. Nerkę prawą bada się w prawym podżebrzu, wykorzystując wątrobę jako „okno ultradźwiękowe”. Nerkę lewą bada się w okolicy lewego podżebrza, najlepiej w linii pachowej tylnej. Badanie ultrasonograficzne moczowodów, w ich górnym odcinku, wykonuje się po badaniu nerek, w przypadku poszerzenia układu kielichowo-miedniczkowego. Warunkiem dobrze przeprowadzonego badania przypęcherzowego odcinka moczowodu jest wypełnienie pęcherza moczowego. Badanie pęcherza moczowego wykonywane jest, przy jego wypełnieniu, w przekrojach poprzecznym i podłużnym oraz w przekrojach skośnych.

Opis badania

Opis powinien zawierać dane pacjenta, dane jednostki kierującej, jednostki wykonującej, dane lekarza wykonującego badanie, typ aparatu oraz głowic, a także tekst właściwego opisu badania.

Introduction

Urinary tract ultrasound (US) imaging in adults and in children constitutes an integral part of each abdominal US examination. US examination of the urinary tract encompasses the assessment of the kidneys (e.g. their location, size and echostructure) as well as the urinary bladder and if there are disorders in urine flow, also of the ureters (as far as they are visible in ultrasonography). The examination of the ureters should determine the cause of their dilatation and specify the level on which a potential obstacle may be localized. Additionally, in men, the size of the prostate gland may be estimated.

Due to the fact that US imaging of the urinary system constitutes a part of abdominal ultrasound examination, it is recommended that it be performed with the fasting patient or several hours after the last meal with filled urinary bladder.

In practice, patients are advised to drink approximately 1.5 liters of still water 1.5–2 hours prior to the examination. The examination should be performed at the moment of urinary urgency(1–12).

Apparatus

US examinations of the urinary tract in adult patients are performed through the transabdominal access (transabdominal ultrasound, TAUS) with sector or convex-type transducers with the frequency of 2.0–6.0 MHz and with color and power Doppler modes. The examination may be supplemented with scans obtained by means of a linear transducer with the frequency of 6.0–9.0 MHz, which enables the assessment of parenchymal organs and lymph nodes in slim patients. Additionally, Doppler ultrasound improves the diagnostic capacity of sonography in terms of differentiation between focal lesions, pseudotumors (e.g. renal dromedary hump, renal column hypertrophy) or disorders in renal vascularity. For ultrasound imaging of the urinary tract in children and infants, sector, convex or linear transducers with higher frequencies are used (5.0–9.0 MHz)(5, 13, 14).

Apart from the transabdominal access, the urinary bladder may also, in certain cases, be visualized transrectally or transvaginally with the use of probes with the frequency of 8.0–10.0 MHz. It is not a routine procedure but it proves useful when there are doubts concerning the diagnosis established on the basis of the transabdominal examination, particularly in the case of lesions localized in the region of the trigone of the urinary bladder and prostatic urethra as well as in the case of considerable obesity and wounds in the hypogastric region of the abdomen. However, because highfrequency transducers are used, it is not possible to evaluate the entire bladder, particularly its anterior wall(15–17).

Scanning technique

Renal examination

The examination of the kidneys in adult patients is performed in the supine and left or right lateral positions while the patients breathe slowly and when they hold their maximal breath (figs. 1, 2). In children, the kidneys are examined transabdominally in the supine position and via lumbar access in the prone position.

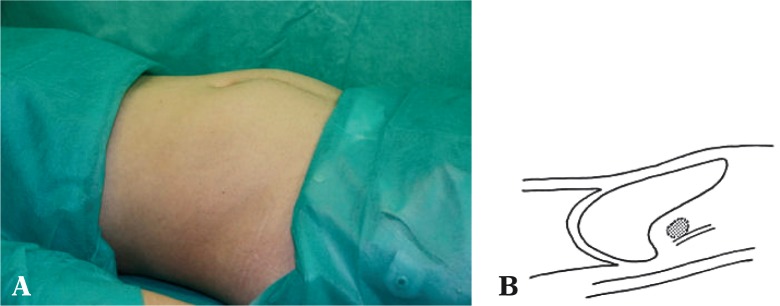

Fig. 1.

Thoracic breathing pattern. The patient draws air into the lungs and the diaphragm is shifted upwards. The organs of the upper abdomen are shifted upwards with the diaphragm and are located behind the ribs

Fig. 2.

Abdominal breathing pattern. The patient draws air into the lungs and the diaphragm moves the liver and kidneys downwards. The kidneys are moved from under the costal margin, which renders ultrasound examination considerably easier

The right kidney is examined with the transducer placed in the right hypochondriac region along the long axis. Subsequently, the transducer is moved from the midclavicular towards the posterior axillary line (fig. 3). The longitudinal axes of normally positioned kidneys converge towards the spine above their upper poles. When the maximal longitudinal section has been obtained, the transducer should be rotated by 90°, which helps obtain a transverse view of the kidney.

Fig. 3.

A, B. US examination of the right kidney. The liver creates an “acoustic window,” which renders the examination easier. C. Normal right kidney. The transducer is placed in the anterior axillary or midaxillary line. The kidney is well-visualized thanks to the liver which “stands in the way” of the ultrasounds running from the probe to the kidney and back. D. Right kidney with visible “parenchymal bridge” which is indicative of duplex pelvicalyceal collective system

The left kidney is assessed by placing the transducer in the left hypochondriac region. As long as the right kidney is visualized thanks to the liver's “acoustic window,” which allows for its imaging in the anterior axillary line, the left kidney is best visualized in the posterior axillary line (fig. 4). The difficulties in imaging may be caused by artefacts formed due to intestinal gases, particularly in the splenic flexure. The kidney should be first visualized in its maximal longitudinal section. Then, transverse views should be obtained. This way its structure from the upper to lower poles should be traced. The invisible lower pole may be a sign of a horseshoe kidney.

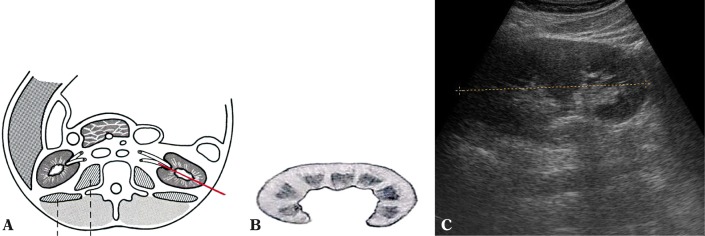

Fig. 4.

A, B. US examination of the left kidney. In order to visualize the left kidney, the transducer should be placed more posteriorly in the posterior axillary line. The plane of the examination usually crosses the splenic hilum. C. Left kidney with hypertrophied column

If the kidneys cannot be visualized in the patient's prone position, the examination should be performed in the right and left lateral or prone positions. If nephroptosis is suspected, the patient should be additionally scanned in the standing position and the distance by which the kidney moves in the standing position as compared to the lying one should be measured. Sometimes, in order to visualize the kidney properly, the transducer must be placed deep under the right of left costal margins and in the intercostal spaces. The application of high-frequency transducers (6.0–9.0 MHz) might also prove useful(12, 18).

If the kidney is not present in its typical location, it should be searched for in the abdominal cavity and pelvis minor.

In the longitudinal view, the normal kidney has a beanlike shape. It consists of the outer hypoechoic echo, which represents the parenchyma composed of the cortical and medullary layers. In children and in certain adults these layers may be differentiated since the renal pyramids and columns, which are parts of the medullary layer, are wellvisible. The hyperechoic central echo (or middle echo, central field) consists of: reflected ultrasounds, walls of non-dilated pelvicalyceal system, blood vessels branching in the region of the renal hilum and connective tissue (fig. 5). In physiologically older patients, an increase of the connective tissue may be observed – fatty degeneration of the renal hilum. In some patients, a slightly filled collecting system, renal pelvis or renal pelvis with the calyces may be detected. Such patients should undergo a repeated examination following miction. If the presentation does not change, this needs to be noted in the description of the examination. In premature infants and neonates the image of the kidneys is different from the image seen in older children and adults – it shows the features of a fetal kidney, i.e. lobar structure with hypoechoic renal pyramids.

Fig. 5.

A, B. Normal image of the kidney. Bean-shaped kidney. The parenchymal layer (cortex and medulla) is seen as a peripheral hypoechoic area. The elements of the non-dilated pelvicalyceal system and vessels of the renal hilum are visible as hyperechoic central echoes. C, D. Renal pyramids are seen in the region of the medullary parenchyma

In normal conditions, the renal parenchyma is characterized by a lower echogenicity than the hepatic parenchyma. It is associated with increased content of water in the renal tissue as a result of intense blood flow through the kidneys.

Each abnormal morphological lesion in the kidney should be described with the specification of its localization, size in three dimensions, echogenicity and echostructure, manner of circumscription from the remaining parenchyma as well as the relation to the central field. Each time, the assessment should be supplemented with the evaluation of vascularity of the lesion in Doppler examination (figs. 6–8). If a neoplastic lesion is suspected, the local lymph nodes should be examined as well as the renal vein and inferior vena cava should be checked for the presence of a tumor-related plugging. The length of the plug ought to be measured as well.

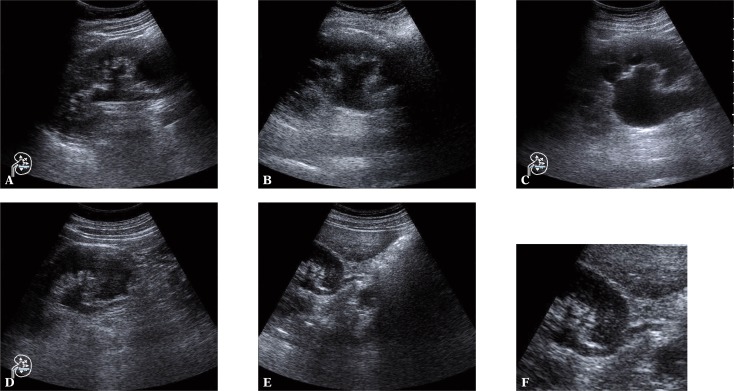

Fig. 6.

Nephrolithiasis: A. a concretion in the lower calyx; B. two concretions – one in the lower calyx, the other in the middle calyx; C. staghorn nephrolithiasis

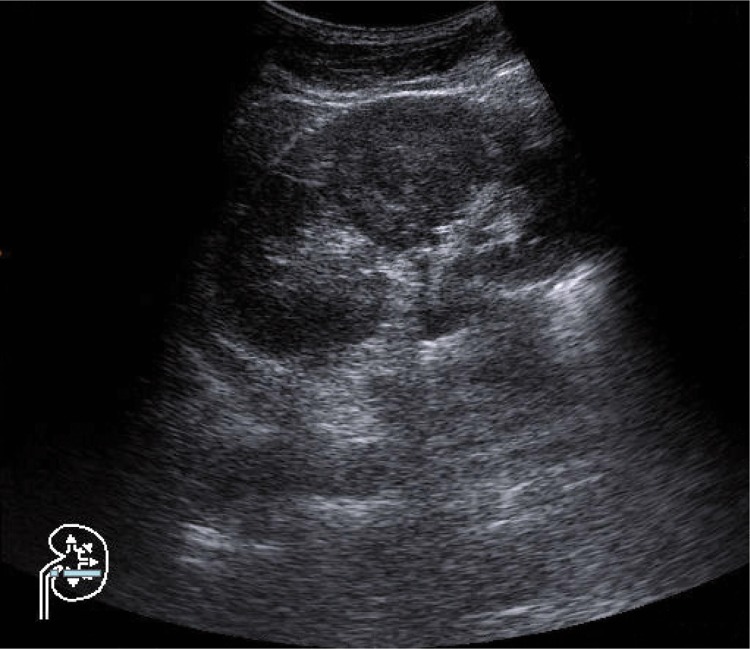

Fig. 8.

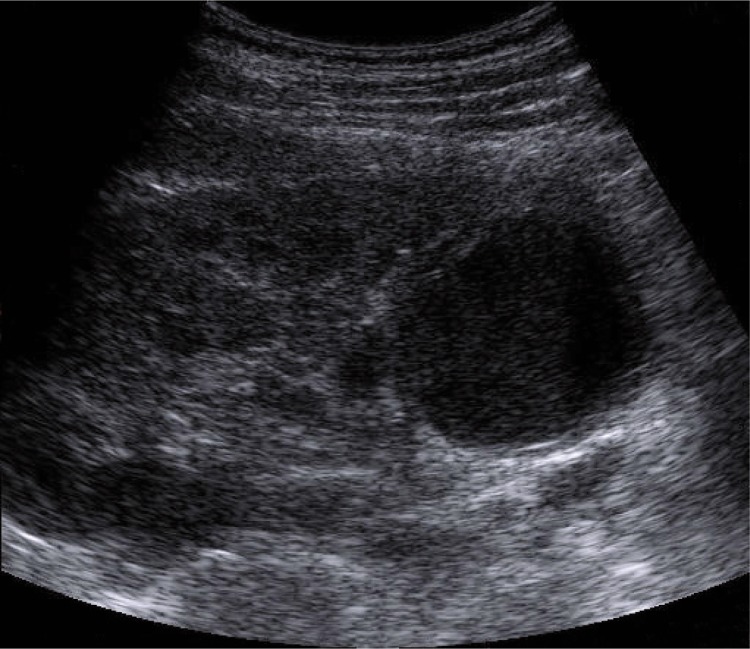

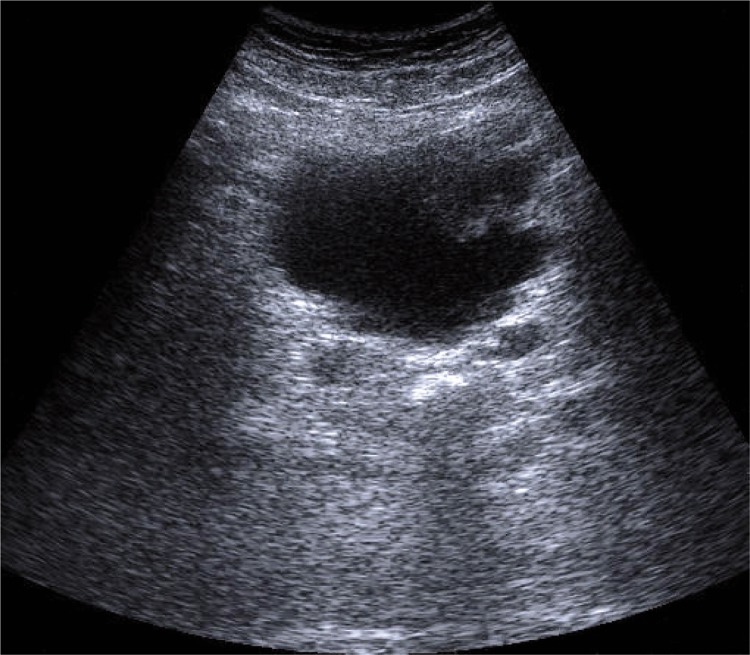

Left kidney. In the central part, a round solid shadow presents renal tumor

Fig. 7.

Left kidney. A hypoechoic, round area in the lower pole of the kidney is a renal abscess (interview: temperature and acute pain in the left lumbar region)

In addition, if tumors of the upper pole are suspected, the adrenal gland should be visualized for differential diagnosis. In the case of cystic lesions, the capsule and their echostructure should be examined (septations, exophytic lesions, calcifications and vascularity)(19–21).

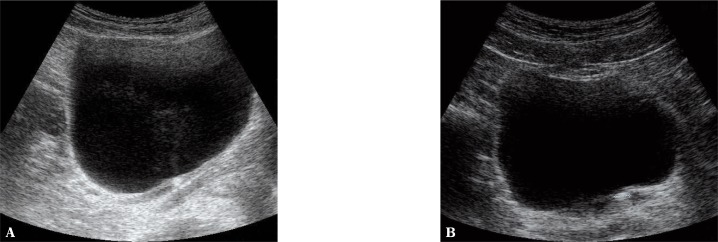

The dilatation of the pelvicalyceal system (fig. 9) may indicate disorders in the urine outflow from the kidney. During US examination, one should assess the region of the ureteropelvic junction and ureteral orifice to the bladder. The image of a “closed” balloon-shaped dilatation of the renal pelvis with coexistent non-dilated ureter may indicate the narrowing of the ureteropelvic junction. Such a narrowing may be a consequence of a dysplasia in the region of the junction or a result of secondary narrowing caused by the vessels running from the lower pole of the kidney and crossing the ureter on this level. Other reasons for pelvic dilatation are: closed, extrarenal pelvis (exact diagnosis is based on functional examinations), urinary retention, urothelial tumor of the upper urinary tract (mainly, of the renal pelvis) and nephrolithiasis which is usually correlated with specific clinical symptoms (fig. 10).

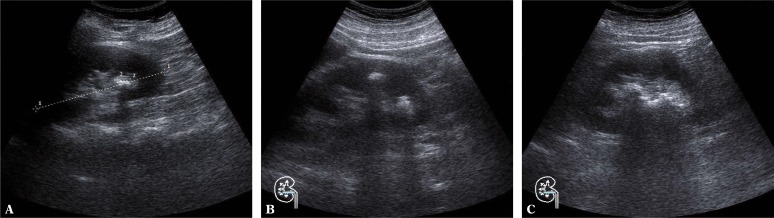

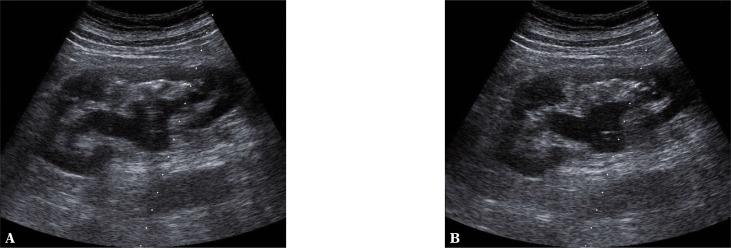

Fig. 9.

A, B. Dilatation of the pelvicalyceal system. The dilatation of the renal pelvis is not accompanied by the widening of the ureter – ultrasound presentation of the dilatation of the ureteropelvic junction. B. A rounded tip of a nephrostomy catheter is visible in the region of the renal pelvis

Fig. 10.

Dilatation of the pelvicalyceal system with dilated upper segment of the ureter. Such a condition requires careful localization of the urine flow obstruction since one of the reasons for urinary retention may be carcinoma of the urinary bladder

In patients with urinary retention in the upper urinary tract (kidneys) detected in the examination, a repeated assessment should be performed after miction. If there is no obstruction in the urine flow, the retention should disappear(3–5).

When the kidneys have been examined, the perirenal tissues should be assessed, particularly the suprarenal areas.

Ureter examination

When considerably dilated, the ureters may be visualized on their entire length only in children and in slim patients. In the remaining cases, it is possible to image only the upper segment and the lower, perivesical portion of the ureters. Their middle parts are generally concealed by intestinal gas.

If the upper segments cannot be visualized in the patient's prone position, the examination should be performed in the right and left lateral or prone positions using the iliopsoas muscle as an “acoustic window.”

In order to visualize the lower segment of the ureter, the urinary bladder needs to be well-filled. The examination begins with placing the transducer transversely slightly above the pubic symphysis and subsequently, moving it transversely in order to visualize the trigone of the urinary bladder and the orifices of both ureters. The entire bladder is assessed on a range of transverse views. The examination may be supplemented with Doppler assessment (color or power Doppler) which enables to observe the jet of urine from both ureters (jet phenomenon) and therefore, constitutes a type of a functional test of the urinary system (figs. 11, 12). It is particularly significant, among others, in patients suffering from renal colic if there are doubts concerning excretory function of the kidneys and patency of the ureters. During the attack of renal colic, the presence of concretions in the ureter should be confirmed or ruled out. If it is present, the dilatation of the ureter is visible above the obstruction site. Generally the concretion itself is visible as well (fig. 12)(22–24).

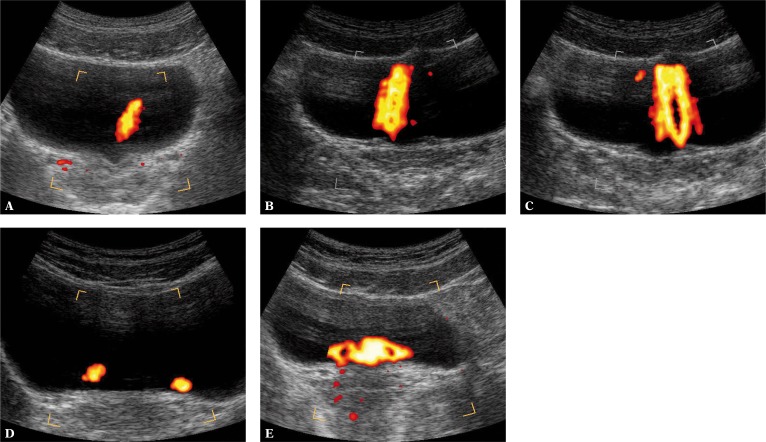

Fig. 11.

Power Doppler in the assessment of renal functions and the inflow of the urine to the bladder: A. transverse section of the trigone of the urinary bladder – the ureteral orifices with perivesical fragments of the ureters and inflow of urine to the bladder; B. outflow of urine from the right ureter; C. outflow of urine from the left ureter; D. simultaneous urinary flow from both ureters with low flow intensity; E. simultaneous urinary flow from both ureters with higher flow intensity causes turbulent outflow and mixing of urine from both ureters

Fig. 12.

Perivesical segments of the ureters: A. right ureter with a concretion localized just above the orifice to the bladder. Turbulent flow of urine to the bladder is seen without power Doppler mode; B. left ureter with a concretion in the orifice to the bladder

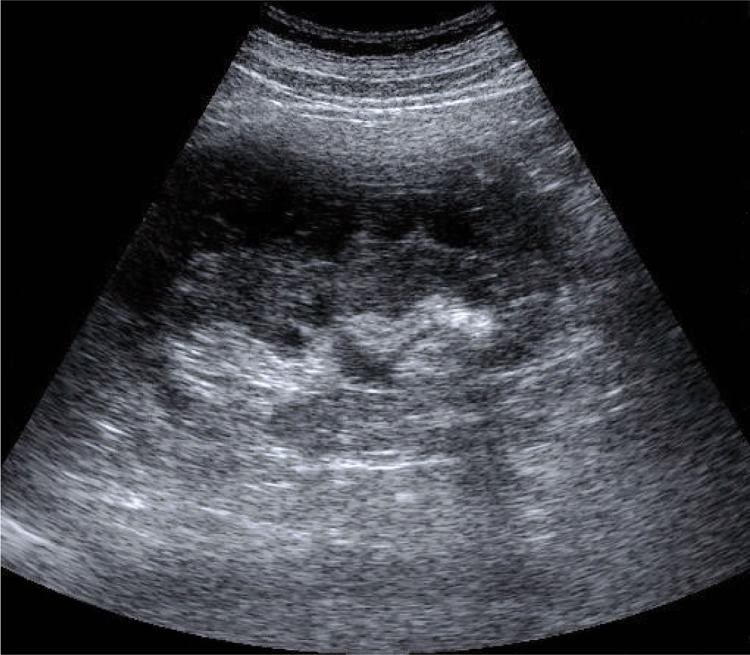

Urinary bladder examination

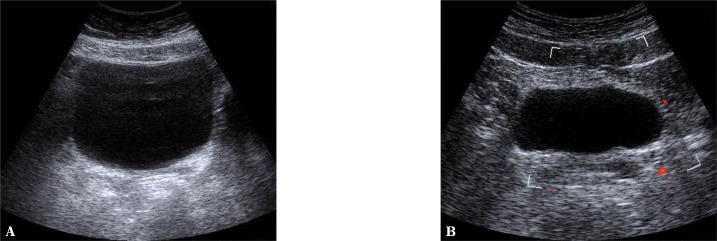

The transabdominal examination of the urinary bladder is performed with the patient in the supine position. The condition for a properly conducted examination is full bladder (the patient should report strong urge to urinate)(15–17, 25).

Transverse, longitudinal and oblique views of the urinary bladder should be obtained. One should assess its shape (normal – round, neurogenic – tower-like) and degree of filling (its volume). Furthermore, it is necessary to assess its walls, including their thickness, outlines, presence of diverticula and mural exophytic lesions, as well as the trigone of the bladder and both orifices of the ureters. Frequently, such an examination may help detect the turbulent outflow of the urine from the ureteral orifices. Such an outflow may be more accurately visualized when Doppler option is used (figs. 11–14).

Fig. 14.

Transverse view of the bladder. Irregularities of the left wall indicate the presence of a neoplasm

Fig. 13.

A. Ultrasound examination of the urinary bladder – transverse view. B. Transverse view of the bladder. The trigone of the bladder with ureteral orifices and interureteric fold

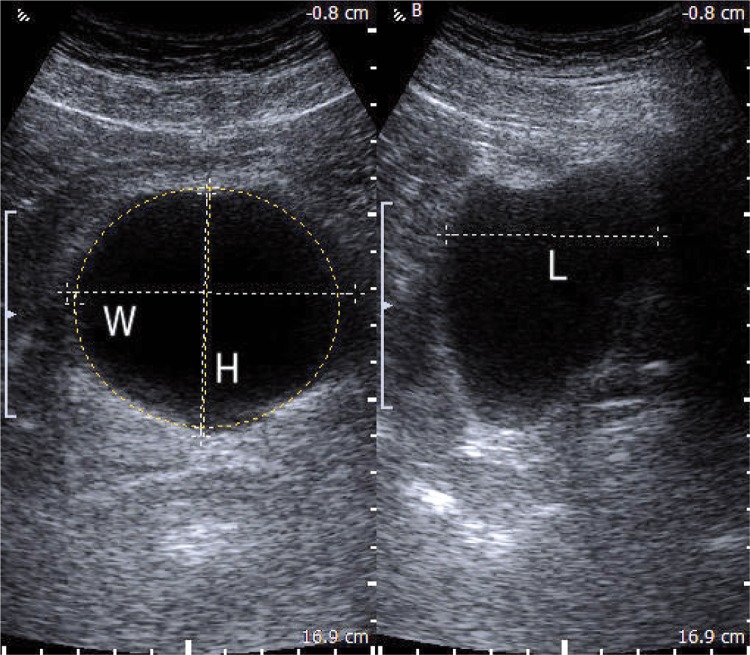

When it is necessary to measure the volume of the urinary bladder and assess the amount of residual urine after miction, the automatic volume-measuring modes are applied which constitute a part of ultrasound software and are characterized by the highest measurement accuracy. In the majority of cases, these methods are based on the measurements with the use of the prolate ellipsoid equation (V = π/6 × width W × height H × length L). It requires taking accurate measurements of the urinary bladder in two perpendicular planes in their maximal sections. It should be remembered that the results are burdened with calculation errors which cannot be avoided(26–36) (fig. 15).

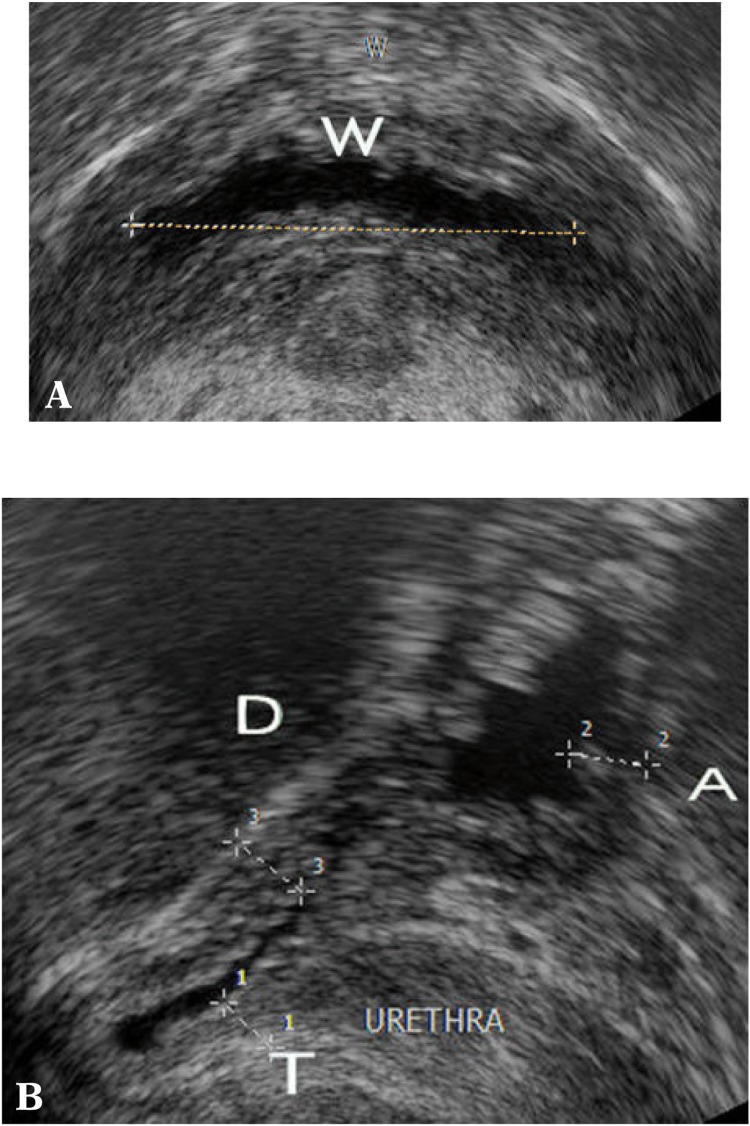

Fig. 15.

Bladder volume measurement. The width (W) of the bladder should be taken in the maximal transverse section as a leftright dimension. The length (L) of the bladder should be taken in the maximal longitudinal section as a superoinferior (cephalocaudal) dimension. Depending on experience, the anteroposterior dimension, i.e. the height (H) of the bladder, may be measured both in the transverse and longitudinal views. One should bear in mind, however, that it should be the greatest distance between the examined walls

When the examination aims at measuring the thickness of the bladder wall in women, a different approach should be adopted. The examination should be performed with minimally filled bladder with the use of a transvaginal probe with the frequency of 8–10 MHz. The urinary bladder must not contain more than 30 ml of urine. Each patient should pass urine prior to the examination which is performed approximately 15 minutes after miction. The measurements of the thickness of the wall are performed in specifically defined locations, i.e. the trigone, apex and anterior wall of the bladder. This makes the examination comparable and reproducible. The measure of the thickness of the bladder wall is used for differential diagnosis in neurogenic dysfunctions of the bladder, detrusor muscle hyperfunction and chronic pelvic pain syndrome (fig. 16)(25).

Fig. 16.

Thickness of the bladder wall measured with minimal (approximately 30 ml) amount of urine: A. transverse view; B. longitudinal view. T – trigone of the bladder, D – apex of the bladder, A – anterior wall, W – width of the bladder

In patients with urological trauma, particular attention should be paid to the integrity of the renal parenchyma, presence of intrarenal and perirenal fluid collections, presence of fluid in the retroperitoneal space, in the pelvis minor and the degree of filling of the bladder. According to the standards of the European Association of Urology, computed tomography (CT) is a method of choice. US examination is the first choice test performed in the ambulance when the patient is being transported to the hospital. Its aim is to initially assess the extent of the injury but it may also be used to monitor the regression of posttraumatic lesions (e.g. absorption of subcapsular hematoma) (fig. 17)(37–40).

Fig. 17.

US examination of the left kidney. The hypoechoic area along the entire organ represents posttraumatic subcapsular hematoma

Description of the examination

Each examination description should include the following details:

patient details (name and surname, date of birth and/or patient identification number);

details of the referring unit;

name of the unit which carried out the examination;

type of US apparatus and transducers used during the examination;

description of the examination;

details of the examining physician.

Kidneys

First of all, the description of renal US examination should specify the localization of the kidneys (normal or abnormal). In the case of ectopic kidney, its localization should be provided and in excessively floating kidney, the description should include the range of its movement.

Moreover, the size of the kidneys ought to be provided as well, including the greatest longitudinal (length) and the greatest transverse (thickness) dimensions as well as two dimensions of parenchymal width – in its thickest and thinnest areas.

The description should include the assessment of the outlines of the kidneys (e.g. even/uneven – altered by inflammation) and the echogenicity of its parenchyma in relation to the echogenicity of the liver (for the right kidney) and of the spleen (for the left kidney).

If focal lesions are detected, the following should be noted in the description: their number, localization, echogenicity and echostructure, size in three dimensions as well as the manner of circumscription from the renal parenchyma (presence or absence of a pseudocapsule). Moreover, their vascularity should be assessed (especially in the case of complex cysts and qualification to CT). All solid focal lesions (apart from a typical presentation of angiomyolipoma), complex cysts and other lesions with ambiguous US images constitute an indication for CT.

Solid lesions which develop in the region of the central field arouse suspicions of a neoplasm that arises from the transitional epithelium of the pelvicalyceal system (transitional cell carcinoma, TCC). These lesions may be visualized during US examination only when the fragment of or entire pelvicalyceal system is distended. Due to the fact that a TCC tumor may have multifocal character, i.e. may involve the kidney, ureter and bladder, all these structures must be thoroughly assessed, as enabled by ultrasonography.

A characteristic hyperechoic tumor in the kidney is angiomyolipoma (AML). With its unambiguous presentation during US examination and the size below 4 cm, only a periodical US monitoring of its size is indicated. In the remaining cases, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging should be scheduled(19–21).

When cystic lesions are visualized, one should measure them, specify their localization (parapelvic or cortical cysts) and assess their lumina and capsules in terms of character differentiation. The structure of renal cystic masses is best reflected by Bosniak classification which has been prepared for computed tomography but is also imported for sonographic purposes(19).

Furthermore, in the description of pelvicalyceal dilatation, its degree should be provided (subjective retention scale: slight, moderate and large) including the size of the calyces (in diameter), renal pelvis and thickness of the renal parenchyma. A common error is mistaking hydronephrosis for large urinary retention. The parameter which may help in the diagnosis is the thickness of the parenchyma which in urine retention remains normal but its thinning is a characteristic sign of hydronephrosis.

In nephrolithiasis, the number, size and localization of calculi should be provided including the indication whether their localization obstructs urine flow from the kidney. Furthermore, it is vital to note whether nephrolithiasis manifests itself as a conventional hyperechoic reflection with consequential acoustic shadow or whether it is merely a focal hyperechoic reflection in the central echo of the kidney, which requires the differentiation with several lesions presenting similar images(24, 41, 42).

What is more, the description should also encompass abnormal perirenal lesions (such as hematoma, inflammatory infiltration, lymphoma or enlarged lymph nodes) as well as possible adrenal pathologies.

The description should be ended with diagnostic conclusions including indications for further diagnostic examinations (such as plain X-ray, urography, computed tomography or scintigraphy) or, if necessary, for a consultation with a specialist.

The photographic documentation of detected abnormal morphological changes should be enclosed.

Ureters

In the upper segment of the ureter (proximal, renal), one should specify the length and width of the visualized, dilated fragment as well as the number and size of concretions or solid masses localized in the ureters, if such have been visualized.

In the lower segment (distal, perivesical), the length and diameter of the visualized ureter should be provided together with a visible cause of dilatation (concretion, neoplastic lesion of the ureter or bladder infiltrating the ureteral orifice).

Urinary bladder

The description of the examination should contain the information concerning: shape, volume, wall outline, estimated size of the prostate gland and volume of residual urine following miction. If any focal pathologies are detected, their number, localization and size should be specified. US examination allows for the differentiation of concretions and clots, which shift with the change of patient's position, from carcinomas that infiltrate the wall. If the latter is found, the size of the lesion should be specified, particularly the width of its base.

The description should be ended with diagnostic conclusions including indications for further diagnostic examinations (such as cystoscopy, plain X-ray, urography, computed tomography) or, if necessary, for a consultation with a urologist.

The photographic documentation of detected abnormal morphological changes should be enclosed.

Conflict of interest

Authors do not report any financial or personal links with other persons or organizations, which might affect negatively the content of this publication and/or claim authorship rights to this publication.

References

- 1.American Urological Association (AUA), American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) AIUM Practice Guideline for the Performance of an Ultrasound Examination in the Practice of Urology; Effective November 5, 2011 – AIUM PRACTICE GUIDELINES – Ultrasound in the Practice of Urology. Available from: www.aium.org. [Google Scholar]

- 2.ACR–AIUM–SPR–SRU Practice Guideline for the Performance of an Ultrasound Examination of the Abdomen and/or Retroperitoneum; Revised 2012 (Resolution 29). Available from: www.acr.org/guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marciński A. Badanie układu moczowego i nadnerczy – wady układu moczowego. In: Marciński A, editor. Ultrasonografia pediatryczna. Warszawa: San Media Wydawnictwo Medyczne; 1994. pp. 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuigham PF, Bishoff JT. Urinary tract imaging: basic principles. In: Dougal WS, Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campwell-Walsh Urology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2013. pp. 99–139. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jakubowski W. USG ukladu moczowo-plciowego. Ogólnopolski Przegląd Medyczny. 2008;6:46–48. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sowińska-Neuman L. Umiejętność samodzielnego wykonywania badań ultrasonograficznych w praktyce lekarza rodzinnego. Ultrasonografia. 2009;9(38):51–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banaszkiewicz A, Dziekiewicz M, Pęczkowska B. Badanie ultrasonograficzne jamy brzusznej u dzieci. Standardy Medyczne Pediatria. 2011;8(2):297–299. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Placzyńska M, Lichosik M, Jung A. Przydatność badania ultrasonograficznego jamy brzusznej u dzieci jako badania przesiewowego. Pediatr Med Rodz. 2011;7:236–240. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer PES. Nerki i moczowody. In: Palmer PES, editor. Diagnostyka ultrasonograficzna. 2nd ed. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL; 2000. pp. 167–191. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pędich M. Choroby nerek. In: Marciński A, editor. Ultrasonografia pediatryczna. Warszawa: San Media Wydawnictwo Medyczne; 1994. pp. 235–249. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Füeßl HS. Nerki. In: Kremer H, Dobrinski W, editors. Diagnostyka ultrasonograficzna. Wrocław: Urban & Partner; 1996. pp. 191–217. 1st Polish ed., edited by Jakubowski W. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudoł-Szopińska I, Szopiński T. Nerki. In: Sudoł-Szopińska I, Szopiński T, editors. Diagnostyka ultrasonograficzna w urologii. Seria Wydawnicza „Praktyczna Ultrasonografia. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2007. pp. 19–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jakubowski W, editor. Seria Wydawnicza „Praktyczna Ultrasonografia”. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2004. Diagnostyka ultrasonograficzna w chorobach nerek. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riccabona M, Avni FE, Damasio MB, Ording-Müller LS, Blickman JG, Darge K, et al. ESPR Uroradiology Task Force and ESUR Paediatric Working Group – Imaging recommendations in paediatric uroradiology, part V: childhood cystic kidney disease, childhood renal transplantation and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;42:1275–1283. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2436-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szopiński T, Sudoł-Szopińska I. Pęcherz moczowy. In: Sudoł-Szopińska I, Szopiński T, editors. Diagnostyka ultrasonograficzna w urologii. Seria Wydawnicza „Praktyczna Ultrasonografia. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2007. pp. 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobrinski W. Pęcherz moczowy i gruczoł krokowy. In: Kremer H, Dobrinski W, editors. Diagnostyka ultrasonograficzna. Wrocław: Urban & Partner; 1996. pp. 263–290. 1st Polish ed., edited by Jakubowski W. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmer PES. Pęcherz moczowy. In: Palmer PES, editor. Diagnostyka ultrasonograficzna. 2nd ed. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Lekarskie PZWL; 2000. pp. 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tyloch J. Badanie usg nerek. In: Jakubowski W, editor. Standardy badań ultrasonograficznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Ultrasonograficznego. 4th ed. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2011. pp. 193–196. Seria Wydawnicza „Praktyczna Ultrasonografia”. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ljungberg B, Bensalah K, Bex A, Canfield S, Dabestani S, Hofmann F, et al. Guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma; European Association of Urology, Guidelines EAU; 2013. pp. 317–373. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacLennan S, Imamura M, Lapitan MC, Omar MI, Lam TBL, Hilvano-Cabungcal AM, et al. UCAN Systematic Review Reference Group; EAU Renal Cancer Guideline Panel Systematic review of oncological outcomes following surgical management of localised renal cancer. Eur Urol. 2012;61:972–993. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Donat SM, Diaz M, Bishoff JT, Coleman JA, Dahm P, Derweesh IH, et al. Follow-up for Clinically Localized Renal Neoplasms. American Urological Association, AUA Guidelines. 2013:1–33. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smereczyński A, Kołaczyk K, Bojko S, Gałdyńska M, Bernatowicz E. Kamica moczowodowa – próba optymalizacji badania ultrasonograficznego. Ultrasonografia. 2011;11(45):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tyloch J. Badanie usg moczowodów. In: Jakubowski W, editor. Standardy badań ultrasonograficznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Ultrasonograficznego. 4th ed. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2011. pp. 197–200. Seria Wydawnicza „Praktyczna Ultrasonografia”. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Türk C, Knoll T, Petrik A, Sarica K, Skolarikos A, Straub M, et al. Guidelines on Urolithiasis; European Association of Urology, Guidelines EAU; 2013. pp. 985–1084. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tyloch J. Badanie usg pęcherza moczowego. In: Jakubowski W, editor. Standardy badań ultrasonograficznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Ultrasonograficznego. 4th ed. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2011. pp. 201–204. Seria Wydawnicza „Praktyczna Ultrasonografia”. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyloch J. Przydatność badania ultrasonograficznego do pomiaru pojemności pęcherza moczowego i oceny ilości zalegającego moczu – porównanie dokładności kilkunastu sposobów pomiaru. Ultrasonografia. 2002;2(7):86–91. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyloch J. Własna metoda pomiaru pojemności pęcherza moczowego i oceny ilości zalegającego moczu. Ultrasonografia. 2002;2(7):92–96. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyloch J. Ocena dokładności własnej metody pomiaru pojemności pęcherza moczowego i zalegania moczu u chorych z asymetrycznym, niekształtnym pęcherzem moczowym. Ultrasonografia. 2002;2(7):97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tyloch J, Bożiłow W, Sawicki K, Krakowiak J, Tyloch F, Kwiatkowski S. Błędy pomiarowe w ultrasonograficznych badaniach morfometrycznych stercza. Ultrasonografia Polska. 1995;5(4):57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babjuk M, Burger M, Zigeuner R, Shariat S, Van Rhijn B, Compérat E, et al. Guidelines on Non-muscle-invasive Bladder Cancer (TaT1 and CIS); European Association of Urology, Guidelines EAU; 2013. pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rouprêt M, Babjuk M, Compérat E, Zigeuner R, Sylvester R, Burger M, et al. Guidelines on Urothelial Carcinomas of the Upper Urinary Tract; European Association of Urology, Guidelines EAU; 2013. pp. 43–64. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witjes JA, Compérat E, Cowan NC, De Santis M, Gakis G, Lebret T, et al. Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer; European Association of Urology, Guidelines EAU; 2013. pp. 65–146. 1–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oelke M, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, Emberton M, Gravas S, Michel MC, et al. Guidelines on the Management of Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), incl. Benign Prostatic Obstruction (BPO); European Association of Urology, Guidelines EAU; 2012. pp. 457–530. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rouprêt M, Babjuk M, Compérat E, Zigeuner R, Sylvester R, Burger M, et al. European guidelines on upper tract urothelial carcinomas: 2013 update. Eur Urol. 2013;63:1059–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Babjuk M, Burger M, Zigeuner R, Shariat SF, van Rhijn BWG, Compérat E, et al. EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: update 2013. Eur Urol. 2013;64:639–653. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stenzl A, Cowan NC, De Santis M, Kuczyk MA, Merseburger AS, Ribal MJ, et al. Treatment of muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: update of the EAU guidelines. Eur Urol. 2011;59:1009–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tyloch J. Badanie usg w urazach nerek i pęcherza moczowego. In: Jakubowski W, editor. Standardy badań ultrasonograficznych Polskiego Towarzystwa Ultrasonograficznego. 4th ed. Warszawa – Zamość: Roztoczańska Szkoła Ultrasonografii; 2011. pp. 364–366. Seria Wydawnicza „Praktyczna Ultrasonografia”. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasławski M, Kołtyś W, Złomaniec J, Szafranek J. Diagnostyka obrazowa urazów nerek. Ann Univ Mariae Curie Sklodowska Med. 2004;59:328–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Summerton DJ, Djakovic N, Kitrey ND, Kuehhas F, Lumen N, Serafetinidis E. Guidelines on Urological Trauma; European Association of Urology, Guidelines EAU; 2013. p. 1211.p. 1292. 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Summerton DJ, Kitrey ND, Lumen N, Serafetinidis E, Djakovic N, European Association of Urology EAU guidelines on iatrogenic trauma. Eur Urol. 2012;62:628–639. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marciński A. Pomyłki i błędy w ultrasonografii pediatrycznej. Ultrasonografia. 2005;5(21):14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marciński A. Pomyłki i błędy w ultrasonografii pediatrycznej. Ogólnopolski Przegląd Medyczny. 2006;4:26–32. [Google Scholar]