Abstract

Branchial cleft cysts are common causes of congenital neck masses in the pediatric population. However, neonatal presentation of branchial cleft cysts is uncommon, but recognizable secondary to acute respiratory distress from airway compression or complications secondary to infection. We report a 1-day-old infant presenting with an air-filled neck mass that enlarged with Valsalva and was not associated with respiratory distress. The infant was found to have a third branchial cleft cyst with an internal opening into the pyriform sinus. The cyst was conservatively managed with endoscopic surgical decompression and cauterization of the tract and opening. We review the embryology of branchial cleft cysts and current management.

Keywords: branchial cleft cyst, neonate, air-filled neck mass

Branchial cleft cysts are the second most common congenital mass of the neck in children and account for 20% of congenital neck masses. Embryologically, the branchial apparatus develops between weeks 2 and 7 of fetal life.1 Persistence of branchial remnants may lead to the formation of cysts, fistulae, or sinuses. The second branchial cleft defect is most common, accounting for more than 90% of the cases of branchial cleft anomalies. Third and fourth branchial cleft defects are uncommon and usually present later in life.2 3 4 However, case reports exist of these anomalies presenting in the newborn period,5 6 usually related to acute respiratory distress. We report a 1-day-old infant in whom a branchial cyst presented as an air-filled neck mass that enlarged with Valsalva.

Case Presentation

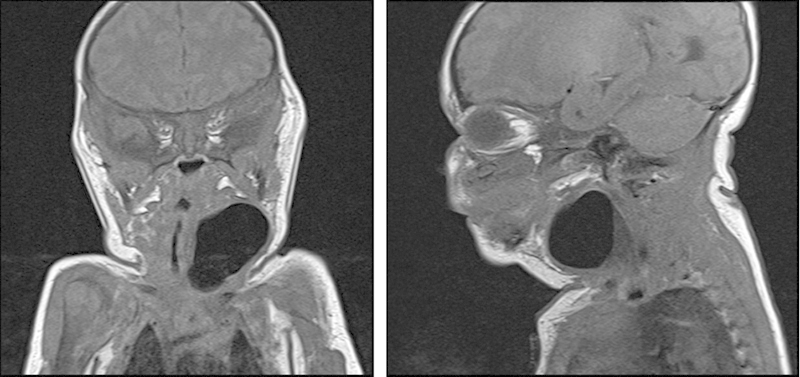

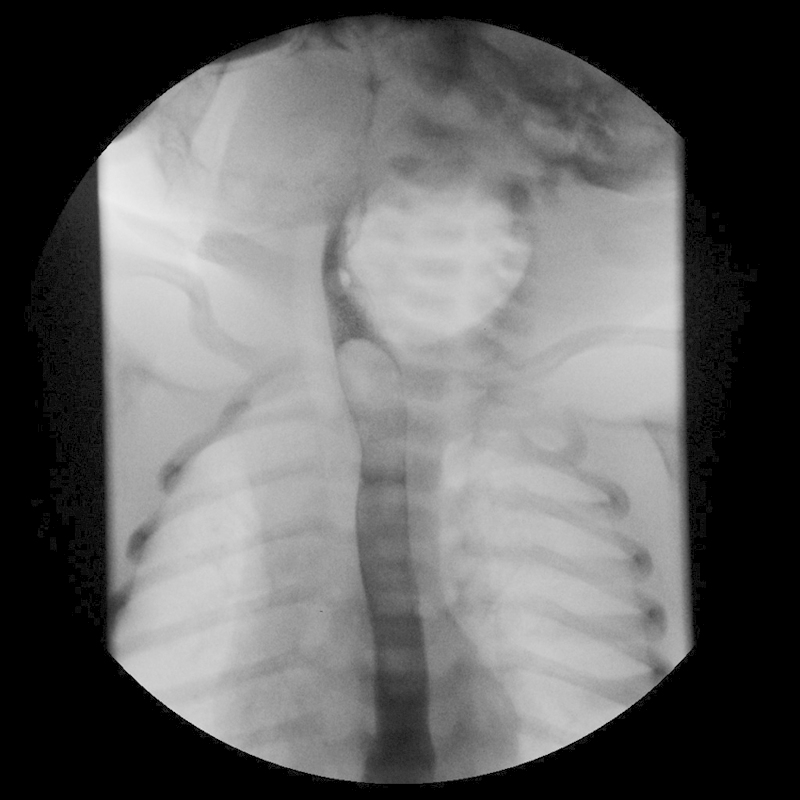

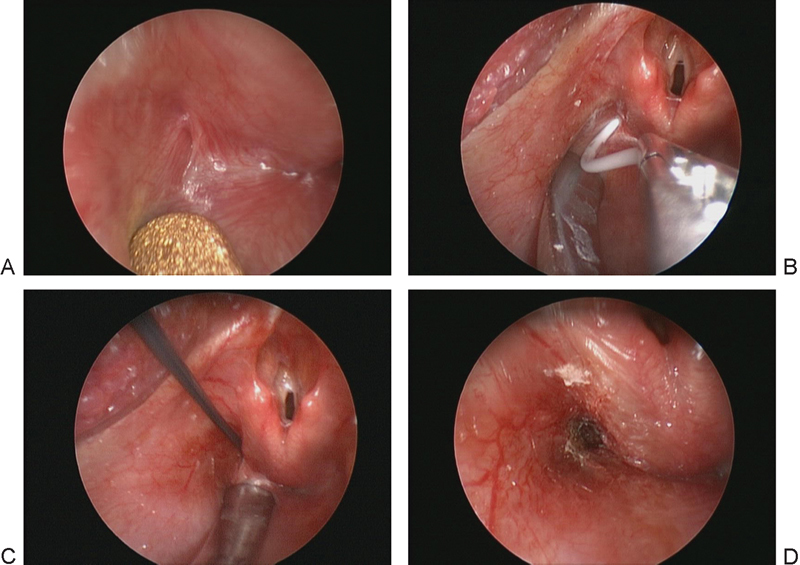

A male infant presented to the neonatal service following spontaneous vaginal delivery at home to a 24-year-old mother who had no prenatal care. The infant appeared well at birth, but was brought to a hospital for evaluation and initial newborn care. At 12 hours of age, he was noticed to have a left-sided, 3 × 3 cm soft, fluctuant, anterior triangle neck mass, which appeared to be gradually increasing in size and was noticeably larger during crying and agitation. No pits, discoloration, or discharge were noted externally. The infant had associated mild inspiratory stridor when agitated, but otherwise normal physical examination findings. He tolerated feeding and was stable in room air with normal arterial saturation. Studies included a normal chest roentgenogram, blood gas analysis, complete blood count, and basic metabolic profile on admission. The pediatric ear-nose-throat (ENT) service was consulted and performed nasopharyngoscopy at the bedside, revealing the lateral pharyngeal fullness with effacement of the pyriform sinus on the left side and right-sided shift of the larynx but no concern for immediate airway obstruction. Ultrasound imaging of the neck revealed a 3.1 × 2.7 cm, nonvascular air-filled neck mass without fluid. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck (Fig. 1) demonstrated a 4.5 cm predominantly air-filled mass in the lateral aspect of the neck, with a small air-fluid level. The differential diagnosis included external laryngocele, lateral cervical esophageal diverticulum, branchial cleft anomaly, and cervical foregut duplication cyst. An esophagogram was performed (Fig. 2), which demonstrated extrinsic mass effect on the cervical esophagus from the adjacent left neck gas collection, but no communication between the cyst and the esophagus. The infant was taken to the operating room by the ENT service for microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy, which revealed a distinct mucosal tract originating from the left pyriform sinus (Fig. 3). The tract was cannulated with a small suction catheter and the mass instantly decompressed, confirming the diagnosis of a branchial cleft sinus. Because there were no signs of infection at this time, the decision was made to proceed initially with conservative management of the cyst. Endoscopic cauterization of the sinus tract and opening was performed using a monopolar electrocautery catheter. The infant tolerated the procedure well without complication. He remained stable after surgery without postoperative reaccumulation and was discharged home on day of life 6.

Fig. 1.

MRI of the neck showing a4.5 cm mass in the lateral aspect of the neck, with small air-fluid level. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Fig. 2.

Esophagogram showing extrinsic mass effect on the cervical esophagus from the adjacent left neck gas collection but no communication with the esophagus.

Fig. 3.

Direct laryngoscopy. (A) Endoscopic view of the left pyriform sinus. Note the small mucosal-lined opening at the lateral aspect of the sinus. (B) Placement of a small catheter endoscopically, resulting in immediate deflation of the mass and verifying the diagnosis. (C) Electrocautery catheter device being inserted into the tract. (D) Postoperative view of the cauterized sinus tract.

At day of life 10, however, the infant was readmitted for swelling on the left side of his neck and mild inspiratory stridor. Ultrasound imaging revealed a 3 cm fluid-filled neck mass with a small focus of air. The mass was decompressed at the bedside with simple needle aspiration without complication. At his last follow-up in the outpatient clinic at 13 months of age, he was healthy with a normal neck examination and no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

We report an atypical presentation of branchial cleft cyst in a 12-hour-old neonate with an air-filled neck mass, which enlarged with Valsalva. The branchial apparatus begins to develop in the 2nd week of fetal life and completes development by the 7th week of fetal life.1 Branchial arches develop from mesoderm and separate externally by ectodermal-lined clefts and internally by endodermal-lined pouches. Branchial anomalies occur following maldevelopment of the branchial apparatus; these are classified as cyst, sinus, or fistula.7 A cyst is an epithelial-lined structure with limited or no opening in the skin or pharynx. A sinus is a blind tract with an opening either externally to the skin or internally to the pharynx. A fistula is a continuous tract communicating externally to the skin and internally to the pharynx.8

Branchial cleft anomalies are the second most common cause of congenital pediatric neck masses, thyroglossal duct cyst being the most common.9 Most branchial cleft anomalies are generally derivatives of the second arch (> 90%).4 9 Third and fourth branchial cleft anomalies are much less common, with third branchial cleft anomaly representing 2 to 8% and fourth branchial cleft anomaly representing 1 to 2% of these anomalies.2 3 4 In addition, third and fourth branchial cleft anomalies commonly present in older children, with a median age of presentation of 5 and 9 years, respectively.10 11 Although rare, neonatal presentations of third branchial cleft cysts have been reported in the literature.2 3 6 8 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 The presentation of both third and fourth branchial cleft cysts typically begins with left-sided acute lateral neck swelling, pain, and fever, findings suspicious for either neck abscess or acute suppurative thyroiditis with or without upper respiratory tract infection. Atypical presentations with respiratory distress or with a cutaneous discharging fistula have also been reported, and respiratory distress is more likely for those in the neonatal period.10 11 However, our patient was unusual in that he did not have respiratory distress or acute infectious complications. Most third and fourth branchial cleft cysts appear on the left side as in our patient, and there have been reports of enlargement with swallowing, filling with air and/or fluid.17 26 To our knowledge, this is the first case report of a neonate presenting on the 1st day of life with an air-filled third branchial cleft cyst that enlarged with Valsalva and was not associated with respiratory distress.

Differentiation between third and fourth branchial arch anomalies is problematic by imaging or clinical examination because of similarity in presentation; both may have openings in the pyriform fossa and terminate at the skin of the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.26 If completely excised, they may be distinguished based on the course of the fistula and the relation to the superior laryngeal nerve, although this nerve rarely is identified definitively on dissection. Third branchial cleft defects originate from the base of pyriform fossa, cross the thyrohyoid membrane, and pass superficial to the superior laryngeal nerve.7 27 Fourth branchial cleft defects originate from the apex of pyriform fossa, pass through the cricothyroid membrane, and course deep to the superior laryngeal nerve.27

Differential diagnosis of a lateral neck mass in the neonate includes vascular malformations, neoplasm, thymic cysts, foregut duplication cysts, and external laryngoceles, in addition to branchial arch cysts. Given the air-filled mass in our patient, we considered the possibility of laryngocele. A laryngocele is an air-filled herniation of the saccule of the laryngeal ventricle. External laryngoceles present as cystic swelling anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and may be a rare cause of respiratory distress in the newborn. Foregut duplication cyst is a benign developmental anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract. The majority of these cysts are located in the thorax and abdomen; only 0.3% arises from the head and neck. Infrequently, these cysts present with respiratory distress in the newborn period. Imaging studies usually help to differentiate and localize the lesion.28

Confirmation of the diagnosis of a third or fourth branchial arch anomaly is centered on the ability to demonstrate the origin of the fistulous opening in the pyriform fossa. Diagnostic investigation usually starts with a neck sonogram, which helps to differentiate a vascular mass from an air-filled mass. A barium swallow study or esophagogram may delineate the tract of a branchial sinus if the sinus is freely communicating with the pharynx. Lin and Wang described identification of the sinus tract by barium studies in almost every case.14 However, Park et al reported that barium esophagogram detected the anomaly in only 50% of the cases.29 In our patient, barium esophagogram did not demonstrate a tract. Computed tomographic scan and MRI have also been used to define sinus tracts with limited success.2 10 11 30 In our patient, MRI was done to differentiate a branchial cleft cyst, laryngocele, and foregut duplication cyst, as well as to exclude the mediastinal extension of the mass, which could have major anesthetic implications. This testing was done without risk of radiation or sedation.31 Direct operative laryngoscopy is the most sensitive method for definitive diagnosis of branchial cleft anomalies via visualization of a pit or sinus opening in the pyriform sinus. In addition, this method has the advantage of potential for therapeutic intervention, as performed in our case.

Various methods have been used for treating third or fourth branchial cleft cysts, but no standardized approach has been recommended for the neonatal period due to the rare occurrence. Incision and drainage are the most commonly used methods to treat infected branchial cleft cysts, often for acute swelling due to neck abscess; however, there is a high recurrence rate.10 Open surgical removal of fistulous tracts along with an ipsilateral hemithyroidectomy has the lowest recurrence rate, if it can be performed safely. The incidence of postoperative complications with excision of third and/or fourth branchial cleft cysts and tracts is significantly higher in children under 8 years of age than in older children, and is expected to be high in the neonate.32 Endoscopic cauterization is emerging as an attractive management option for third and fourth branchial cleft anomalies in neonates and young children, with failure rates decreasing with technological advances. Cure rates with endoscopy may now be comparable to open neck surgery, with lower rates of complications.10 Park et al described 15 cases managed by endoscopic cauterization of the pyriform fistula with trichloroacetic acid.29 They demonstrated an 80% success rate in this series with endoscopic cauterization alone, without requiring formal excision. However, the age of patients from this study ranged from 2 to 49 years. No large case series have specifically examined endoscopic cauterization of branchial cleft cysts in the neonatal period.

Our patient did present to us at 10 days of life with a fluid collection in the area of the cyst which was treated with needle decompression with no further complications. This collection may have represented a simple postoperative seroma rather than a recurrence. The cyst lining was cauterized with the intention of promoting the cyst to scar closed from inside out. At this time, the lining may not have had sufficient time to scar closed, resulting in a seroma formation. His last follow-up demonstrated no recurrence at age 13 months. Formal excision will be reserved for clinical evidence of recurrence.

In summary, we present an unusual case of a branchial cleft cyst presenting with an air-filled neck mass that enlarged with Valsalva in a newborn that was diagnosed and managed by direct laryngoscopy with cautery.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wilson D B. Embryonic development of the head and neck: part 2, the branchial region. Head Neck Surg. 1979;2(1):59–66. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890020109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agaton-Bonilla F C, Gay-Escoda C. Diagnosis and treatment of branchial cleft cysts and fistulae. A retrospective study of 183 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;25(6):449–452. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(96)80081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doi O, Hutson J M, Myers N A, McKelvie P A. Branchial remnants: a review of 58 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1988;23(9):789–792. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(88)80223-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford G R, Balakrishnan A, Evans J N, Bailey C M. Branchial cleft and pouch anomalies. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106(2):137–143. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100118900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobs I N, Gray R, Wyly B. Approach to branchial pouch anomalies that cause airway obstruction during infancy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118(5):682–685. doi: 10.1177/019459989811800521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrish T N, Manning S C. Branchial anomaly in a newborn presenting as stridor. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1991;21(3):259–262. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(91)90007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Proctor B, Proctor C. Congenital lesions of the head and neck. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1970;3(2):221–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simpson R A. Lateral cervical cysts and fistulas. Laryngoscope. 1969;79(1):30–59. doi: 10.1288/00005537-196901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenealy J F, Torsiglieri A J Jr, Tom L W. Branchial cleft anomalies: a five-year retrospective review. Trans Pa Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1990;42:1022–1025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicoucar K, Giger R, Jaecklin T, Pope H G Jr, Dulguerov P. Management of congenital third branchial arch anomalies: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142(1):21–2800. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicoucar K, Giger R, Pope H G Jr, Jaecklin T, Dulguerov P. Management of congenital fourth branchial arch anomalies: a review and analysis of published cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(7):1432–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tucker H M, Skolnick M L. Fourth branchial cleft (pharyngeal pouch) remnant. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1973;77(5):ORL368–ORL371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burge D, Middleton A. Persistent pharyngeal pouch derivatives in the neonate. J Pediatr Surg. 1983;18(3):230–234. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(83)80090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin J N, Wang K L. Persistent third branchial apparatus. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26(6):663–665. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(91)90005-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inigués J P Rivron A Priou J P Beust L Le Clec'h G Bourdinière J Fistula of the 4th endo-branchial pouch. Apropos of 4 cases [in French] Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac 19931108450–454., discussion 455 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma H S, Razif A, Hamzah M. et al. Fourth branchial pouch cyst: an unusual cause of neonatal stridor. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;38(2):155–161. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(96)01424-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mouri N, Muraji T, Nishijima E, Tsugawa C. Reappraisal of lateral cervical cysts in neonates: pyriform sinus cysts as an anatomy-based nomenclature. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(7):1141–1144. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90547-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicollas R, Ducroz V, Garabédian E N, Triglia J M. Fourth branchial pouch anomalies: a study of six cases and review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1998;44(1):5–10. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(98)00023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nathan K, Bajaj Y, Jephson C G. Stridor as a presentation of fourth branchial pouch sinus. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126(4):432–434. doi: 10.1017/S0022215112000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung E J, Baek S K, Youn S W, Kim C H, Lee J H, Jung K Y. A case of bilateral intrathyroidal branchial cleft cyst in a newborn. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(1):E1–E4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joshi M J, Provenzano M J, Smith R J, Sato Y, Smoker W R. The rare third branchial cleft cyst. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(9):1804–1806. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Buys Roessingh A S, Quintal M C, Dubois J, Bensoussan A L. Obstructive neonatal respiratory distress: infected pyriform sinus cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(5):E5–E8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang R Y, Damrose E J, Alavi S, Maceri D R, Shapiro N L. Third branchial cleft anomaly presenting as a retropharyngeal abscess. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;54(2-3):167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(00)00355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang T Z, Lin Y J, Tsai S T. Fourth branchial cyst presenting with neonatal respiratory distress. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109(4):431–434. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misawa K, Imai A, Sugiyama K, Seki A, Mineta H. A right-sided fourth branchial cleft cyst: a case report. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;75(3):438–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenfeld R M, Biller H F. Fourth branchial pouch sinus: diagnosis and treatment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;105(1):44–50. doi: 10.1177/019459989110500107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franciosi J P, Sell L L, Conley S F, Bolender D L. Pyriform sinus malformations: a cadaveric representation. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37(3):533–538. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.30866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lipsett J, Sparnon A L, Byard R W. Embryogenesis of enterocystomas-enteric duplication cysts of the tongue. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;75(5):626–630. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90238-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S W, Han M H, Sung M H. et al. Neck infection associated with pyriform sinus fistula: imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(5):817–822. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Souza A R, Uppal H S, De R, Zeitoun H. Updating concepts of first branchial cleft defects: a literature review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;62(2):103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(01)00612-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haney B, Reavey D, Atchison L. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging studies without sedation in the neonatal intensive care unit: safe and efficient. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2010;24(3):256–266. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0b013e3181e8d566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goff C J, Allred C, Glade R S. Current management of congenital branchial cleft cysts, sinuses, and fistulae. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;20(6):533–539. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e32835873fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]