Abstract

To accurately measure gene expression using quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR), reliable reference gene(s) are required for data normalization. Corchorus capsularis, an annual herbaceous fiber crop with predominant biodegradability and renewability, has not been investigated for the stability of reference genes with qRT-PCR. In this study, 11 candidate reference genes were selected and their expression levels were assessed using qRT-PCR. To account for the influence of experimental approach and tissue type, 22 different jute samples were selected from abiotic and biotic stress conditions as well as three different tissue types. The stability of the candidate reference genes was evaluated using geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper programs, and the comprehensive rankings of gene stability were generated by aggregate analysis. For the biotic stress and NaCl stress subsets, ACT7 and RAN were suitable as stable reference genes for gene expression normalization. For the PEG stress subset, UBC, and DnaJ were sufficient for accurate normalization. For the tissues subset, four reference genes TUBβ, UBI, EF1α, and RAN were sufficient for accurate normalization. The selected genes were further validated by comparing expression profiles of WRKY15 in various samples, and two stable reference genes were recommended for accurate normalization of qRT-PCR data. Our results provide researchers with appropriate reference genes for qRT-PCR in C. capsularis, and will facilitate gene expression study under these conditions.

Keywords: jute (Corchorus capsularis), qRT-PCR, reference genes, gene expression, abiotic and biotic stress

Introduction

With the increase of global environmental awareness, more and more people are actively purchasing goods made from ecologically friendly materials. Unfortunately, many of these materials are intrinsically unrecyclable, including many of the predominantly used polymers. However, many natural fibers such as jute and kenaf possess properties that are comparable to more traditional composites, including stiffness, flexibility, impact resistance, and elasticity (Sydenstricker et al., 2003). The overlap between natural fiber properties and those of traditional, reinforced composites are underscored by their environmentally friendly nature. For instance, fiber components are biodegradable, renewable, and result in low energy consumption. Collectively, these characteristics lend natural fibers to being logical substitutes for non-renewable synthetic fibers (Oksman et al., 2003; Corrales et al., 2007).

Jute (Corchorus capsularis L.) is an annual herbaceous fiber crop. It is found predominantly in Southeast Asia and is the second cheapest and most commercially available fiber crop, whereby it provides a biodegradable and renewable lignocellulose fiber. Jute is a promising and featured fiber material among many value-added industrial products, due in large part to its high luster, moisture absorption properties, ability for rapid water loss, and easy breakdown. Furthermore, jute has much potential for use in the industrial production of packaging materials (Sydenstricker et al., 2003). With the recent and increasing interest in jute, work has been conducted to better understand its physiological and biochemical properties (Corrales et al., 2007; del Río et al., 2009; Defoirdt et al., 2010). At a molecular level, several studies have also been done to examine relevant molecular markers (e.g., SSR, ISSR, RAPD, and AFLP) (Qi et al., 2003a,b; Basu et al., 2004; Roy et al., 2006; Mir et al., 2008, 2009), ESTs, stress response factors (Alam et al., 2010), and a transformation system (Chattopadhyay et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2013). However, many of these previous experiments used single or multiple gene expression analysis via classical RT-PCR and/or Northern blot (Alam et al., 2010). Only a handful of studies have used quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) to determine the expression pattern of functional jute genes (Zhang et al., 2013, 2014).

As of this writing, qRT-PCR provides the most efficient, sensitive, low cost, and reproducible method for accurate and rapid detection and quantification of mRNA transcription levels for a given gene of interest (Bustin, 2002). However, several factors including RNA integrity, reverse transcription efficiency, cDNA quality, sample amount, and/or extraneous tissue and cell activities can significantly influence the accuracy of gene expression (Bustin, 2002; Huggett et al., 2005). To lessen these problems, one or more reference genes are required to account for the variance between samples and/or reactions. To this end, the transcription level of an ideal reference gene should remain constant across different tissues, treatments, and developmental stages (Gutierrez et al., 2008). A number of commonly used housekeeping genes (e.g., β-actin, elongation factor 1α, 18S ribosomal RNA, and polyubiquitin) have been used, but results indicated that their expression levels are somewhat unstable. Thus, their use as internal reference genes should be taken with some caution under a given set of experimental conditions (Gutierrez et al., 2008). Taken together, these inconsistencies highlight the need to evaluate the stability of candidate reference genes under the relevant experimental conditions prior to using for gene expression normalization by qRT-PCR.

In recent years, an increasing number of stable reference genes have been studied in several systems, including eukaryotic elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1α) and F-box family protein (FBX) in Arabidopsis thaliana; 18S ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA), ubiquitin5 (UBQ5), and eukaryotic elongation factor 1-alpha (eEF1α) in Oryza sativa (Czechowski et al., 2005; Jain et al., 2006; Remans et al., 2008; Narsai et al., 2010); catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), actin 4 (ACT4), ubiquitin 14 (UBQ14), F-box family protein (FBX6), clathrin adaptor complexes medium subunit family protein (MZA), and polypyrimidine tract-binding protein homolog (PTB) in Gossypium hirsutum (Artico et al., 2010). Furthermore, Zhang et al. and Saraiva et al. both found that EF1α could also be used as a reference gene in Triticum aestivum (Paolacci et al., 2009; Long et al., 2010) as well as in Glycine max (Jian et al., 2008; Libault et al., 2008). Additionally, suitable reference genes for use in gene expression analysis have also been methodically identified for a variety of species, such as Saccharum officinarum (Ling et al., 2014), Litchi chinensis (Zhong et al., 2011), Litsea cubeba (Lin et al., 2013), Citrus sinensis (Mafra et al., 2012), Coffea ssp. (Cruz et al., 2009), Solanum tuberosum (Nicot et al., 2005), Musa acuminata (Chen et al., 2011), Vitis vinifera (Reid et al., 2006), Helianthus annuus (Fernandez et al., 2011), Nicotiana tabacum (Schmidt and Delaney, 2010; Liu et al., 2012), and Linum usitatissimum (Huis et al., 2010). However, no systematic validation of reference genes has been performed in jute (Corchorus capsularis), which prevents further studies on this species at the functional gene expression and transcriptome profile analysis levels.

In the present study, 11 genes were selected as candidate reference genes for evaluation expression stability in jute: 18S ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA), actin (ACT), actin 7 (ACT7), chaperone protein dnaJ (DnaJ), eukaryotic elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1α), ras-related small GTP-binding protein (RAN), alpha-tubulin (TUBα), beta-tubulin (TUBβ), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme like protein (UBC), ubiquitin extension protein (Imai et al., 2014) and ubiquitin (UBQ). We then sought to reveal which reference gene(s) were the best option for gene expression qRT-PCR analysis of jute under various experimental treatments using three available statistical algorithms, geNorm (Vandesompele et al., 2002), NormFinder (Andersen et al., 2004), and BestKeeper (Pfaffl et al., 2004). Finally, we validated the expression levels of the transcription factor CcWRKY15 using the selected reference gene(s). The results from this work will facilitate future studies on gene expression as well as foster a better understanding of how novel genes function in the molecular mechanisms of jute biological and/or physiological processes.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and treatments

Jute (Corchorus capsularis L.) variety Huangma 108 was used for all experimental treatment groups. To ensure disease-free materials, seeds were rinsed under running water for 10 min and sterilized with 5% sodium hypochlorite for 10 min. They were then washed three times with sterile water before germinated on filter paper that had been saturated with water in complete darkness at 28°C. After 3 days, seedlings were grown in the greenhouse in 1/4 Hoagland solution under a 16/8-h light/dark cycle at 30/26°C (day/night). Seedlings were assessed at the 3–5 leaf stage and the most consistent were used for (i) the abiotic and biotic stress groups or for (ii) harvesting of different plant tissues (e.g., root, stem, and leaf).

For the salinity and drought treatments, seedlings were subjected to 200 mM sodium chloride and 15% (w/v) PEG6000, respectively, and harvested at 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h. For the biotic treatment, seedlings were inoculated with 2 ml (106 spores per ml) of Colletotrichum siamense spores in suspension previously described by Ma et al. (2009) and then sampled at 0, 1, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. Tissues from the roots, stems, and leaves were collected from plants in the 3–5 leaf stage that had grown well under the experimental conditions. All samples were harvested from three replicate plants, giving a total of 25 samples comprised of 14 abiotic and eight biotic stress treatment samples and three tissue-specific samples. Samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction.

Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from approximately 100 mg fresh leaf tissue using the OMEGA isolation kit (R6827-01, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The genomic DNA contamination was eliminated using RNase-free DNase I (TaKaRa, Japan) and RNA sample quality was then determined using the NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop, Thermo Scientific). RNA integrity was assessed by 2.0% agarose gel electrophoresis. Finally, RNA samples with an A260/A280 ratio between 1.9 and 2.1 and an A260/A230 ratio greater than 2.0 were used for further analysis. Subsequently, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg total RNA in a volume of 20 μl using the PrimeScript® RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Japan) by following the manufacturer's protocol. All final cDNA samples were diluted 10-fold for subsequent quantitative real-time RT-PCR reactions. Samples were stored at −20°C until use.

Primer design, verification of PCR products, and qRT-PCR

A total of 11 candidate reference genes, including 18S rRNA (FJ527599), ACT (GU207477), ACT7 (GH985158), DnaJ (GR463675), EF1α (GH985217), RAN (FK826494), TUBα (GH985177), TUBβ (JK743820), UBC (GR463733), UBI (GH985256), and UBQ (FK826547), were identified after performing a TBLASTN among the jute expressed sequence tags (ESTs) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nucest/?term=jute). Primers were designed according to these potential reference gene sequences using Primer 3 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/primer3/) and based on the following criteria: GC content 45−80%, melting temperatures 58−62°C, primer lengths 18−24 bp, and amplicon lengths 100−250 bp (See Table 1 for detailed primer information).

Table 1.

Primer sequences and amplicon characteristics of the 11 candidate internal control genes.

| Gene | Gene description | Arabidopsis ortholog locus | Primer sequence F/R (5′–3′) | Product size(bp) | Efficiency (%) | R2 | Mean Ct | SD | CV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18S rRNA | 18S ribosomal RNA | AT3G41768 | CTACGTCCCTGCCCTTTGTA | 175 | 90.1 | 0.997 | 16.85 | 0.78 | 4.63 |

| GGTTCACCTACGGAAACCTTG | |||||||||

| ACT | Actin | AT3G12110 | CATTACCATTGGGGCAGAAC | 168 | 113.7 | 0.991 | 25.75 | 1.31 | 5.09 |

| GAGCCACCACTGAGGACAAT | |||||||||

| ACT7 | Actin 7 | AT5G09810 | ACAATTGGAGCAGAGCGTTT | 166 | 99.52 | 0.997 | 22.24 | 0.92 | 4.14 |

| TAGACCCACCGCTAAGCACT | |||||||||

| DnaJ | Chaperone | AT3G07590 | TGTATGCACCGAGGAAAATG | 154 | 104.1 | 0.999 | 22.22 | 0.75 | 3.38 |

| protein dnaJ | GTGGAAAAATCGTTGGCAAT | ||||||||

| EF1α | Elongation | AT1G07940 | GAAGAAGGACCCATCTGGTG | 130 | 104.2 | 0.990 | 18.28 | 0.94 | 5.14 |

| factor 1-alpha | TCCACAAAACCGCAATGTAA | ||||||||

| RAN | Ras-related small | AT5G59840 | GCCATGCCGATAAGAACATT | 167 | 99.52 | 0.996 | 26.37 | 1.29 | 4.89 |

| GTP-binding protein | GTGAAGGCAGTCTCCCACAT | ||||||||

| TUBα | Alpha-tubulin | AT4G14960 | AATGCTTGCTGGGAGCTTTA | 213 | 98.21 | 0.988 | 28.43 | 2.15 | 7.56 |

| GTGGAATAACTGGCGGTACG | |||||||||

| TUBβ | Beta-tubulin | AT2G29550 | CTGGTTCCTCTTCCTCACCA | 201 | 108.9 | 0.999 | 22.40 | 1.07 | 4.78 |

| ACAAGATGTTCAGGCGTGTG | |||||||||

| UBC | Ubiquitin-conjugating | AT3G52560 | CTGCCATCTCCTTTTTCAGC | 150 | 108.6 | 0.992 | 21.20 | 1.13 | 5.33 |

| enzyme like protein | CGAGTGTCCGTTTTCATTCA | ||||||||

| UBI | Ubiquitin extension | AT2G47110 | CCACTCTCCACCTTGTCCTC | 158 | 108.9 | 0.989 | 21.44 | 0.62 | 2.89 |

| protein | CAGCCTCTGAACCTTTCCAG | ||||||||

| UBQ | Ubiquitin | AT5G20620 | TCTTTGCAGGGAAGCAACTT | 219 | 96.49 | 0.997 | 20.13 | 1.54 | 7.65 |

| CTGCATAGCAGCAAGCTCAC | |||||||||

| WRKY15 | DNA-binding | AT2G23320 | CTTGGACAGCGTTTTCTTCC | 128 | 99.46 | 0.996 | – | – | – |

| Protein WRKY15 | TGAATGGTTTTGGTGCAGAC |

R2, regression coefficient; SD, standard deviation; CV, co-variance.

To check the specificity of the amplicon, all primer pairs were initially tested via standard RT-PCR using the Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa, Japan) and the amplification product of each gene was verified by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel. Real-time amplification reactions were performed with the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (TaKaRa, Japan). Reactions were prepared in a 20 μl volume containing the following: 2 μl cDNA template, 0.4 μl of each amplification primer, 0.4 μl ROX Reference Dye II, 10 μl 2x SYBR Premix Ex Taq™, and 6.8 μl dH2O. Amplifications were performed with an initial 30 s step of 95°C followed by 40 denaturation cycles at 95°C for 5 s and primer annealing at 60°C for 34 s. The melting curve ranged from 60 to 95°C and temperature was increased in increments of 0.2°C every 10 s for all PCR products. ABI Prism Dissociation Curve Analysis Software was used to confirm the occurrence of specific amplification peaks. All qRT-PCR reactions were carried out in triplicate with template-free negative controls being performed in parallel.

Statistical analyses of gene expression stability

To select a suitable reference gene, three publicly available software packages, geNorm (version 3.5), NormFinder and BestKeeper, were used to analyze the stability of each reference gene. All analyses using these packages occurred according to the manufacturers' instructions. For geNorm and NormFinder algorithms, the raw Ct values from the qRT-PCR were transformed into the relative expression levels using the following formula: E−ΔCt, where ΔCt equaled each corresponding Ct value minus the minimum Ct value. Then, the relative expression values were imported into geNorm and NormFinder to analysis gene expression stability. For BestKeeper analysis, the Ct value was used as input data to calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) and the standard deviation (SD). The comprehensive rankings of the best reference genes were obtained by integrating the results of three algorithms. To validate the reliability of the selected reference genes, we analyzed the relative expression levels of the transcription factor CcWRKY15 in all tested samples. Additionally, a standard curve was generated from a 10-fold dilution of cDNA in a qRT-PCR assay using Microsoft Excel 2003. The PCR efficiency (E) and the regression coefficient (R2) were calculated using the slope of the standard curve according to the equation E = [10−(1∕slope) − 1] × 100%. All other multiple comparisons were performed using the statistical analysis software SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., USA).

Results

qRT-PCR data of candidate reference genes

A total of 11 candidate reference genes, including 18S rRNA, ACT, ACT7, DnaJ, EF1α, RAN, TUBα, TUBβ, UBC, UBI, and UBQ, were identified and assessed under abiotic stress (NaCl stress and drought stress), biotic stress (Colletotrichum siamense) and in different tissues in this study. For each gene, the specificity of the designed primers was verified using agarose gel electrophoresis and the subsequent presence of a single band with the expected size (Figure S1), and further confirmed by the presence of a single peak in the melting curve analysis, which was done prior to performing qRT-PCR (Figure S2). As described in Table 1, the amplicon size ranged from 130 to 219 bp. The PCR efficiency (E) was greater than 90% and varied from 90.1% (18S rRNA) to 113.7% (ACT), and the regression coefficient (R2) ranged from 0.988 (TUBα) to 0.999 (DnaJ and TUBβ) (Table 1).

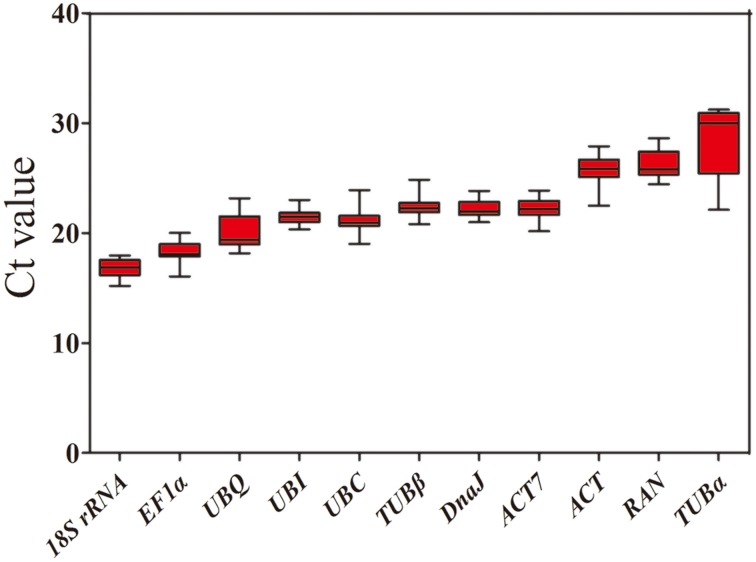

To evaluate stability of the reference genes across all experimental samples, the transcript abundances of the 11 candidate reference genes were detected by their mean Ct values. The Ct values of these candidates varied from 15.22 to 31.28, with the majority falling between 20.13 and 24.40 (Figure 1). Across all samples, 18S rRNA was the most abundantly expressed gene, with the lowest average Ct ± SD (16.85 ± 0.78), followed by EF1α (18.28 ± 0.94), UBQ (20.13 ± 1.54), UBC (21.20 ± 1.13), UBI (21.44 ± 0.62), DnaJ (22.22 ± 0.75), ACT7 (22.24 ± 0.92), and TUBβ (22.40 ± 1.07). TUBα was found to have the lowest level of expression of any of the genes tested, with a mean Ct ± SD of 28.43 ± 2.15, followed by RAN (26.37 ± 1.29) and ACT (25.75 ± 1.31) (Table 1). Small co-variance (CV) of the Ct value indicates that a given gene is more stably expressed. Among these 11 candidate reference genes, UBQ showed the greatest variation with CV value of 7.65%, whereas both UBI (2.89%) and DnaJ (3.38%) showed the least variation in their expression levels across all tested samples. The ranking of gene stability by CV was as follows: UBI > DnaJ > ACT7 > 18S rRNA > TUBβ > RAN > ACT > UBC > TUBα > UBQ (Table 1). Collectively, these results indicate that the transcript levels of the candidate reference genes varied across different experimental samples. Thus, it is essential to screen the most appropriate reference genes in jute in order to normalize gene expression analysis.

Figure 1.

Expression levels of 11 candidate reference genes across all experimental samples. The box graph indicates the interquartile range, the median, and maximum/minimum values.

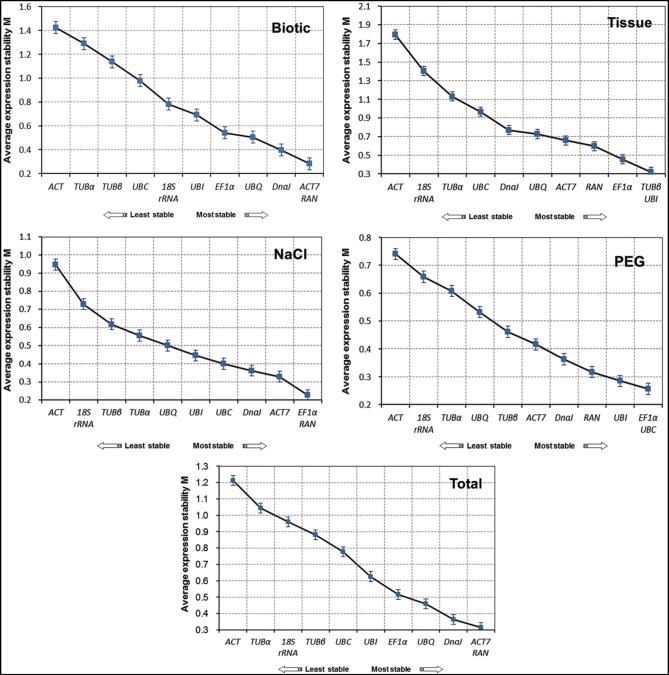

Stability analysis of reference genes by genorm

A geNorm-based analysis was carried out to determine which candidate reference gene(s) would be optimal in each of the tested samples sets. As shown in Figure 2, genes were ranked according to their M values. Since a lower M value indicates increased stability, RAN, and ACT7 were determined to be the most stable reference genes in total samples. In contrast, TUBα and ACT were the least stable reference genes. For each subset of the treatment, the top two reference genes for qRT-PCR normalization were ACT7 and RAN in biotic stress subset, TUBβ, and UBI in different tissues, EF1α and RAN for NaCl stress, and EF1α and UBC for drought stress. In general, the most stable genes across all experimental samples were RAN and ACT7, while TUBα, ACT, and 18S rRNA were the least stable (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Expression stability of 11 candidate genes in jute as calculated by geNorm. Mean expression stability (M) was calculated following stepwise exclusion of the least stable gene in biotic stress samples, tissue samples, NaCl- and PEG-treated samples and all samples. The least stable genes are on the left and the most stable genes on the right.

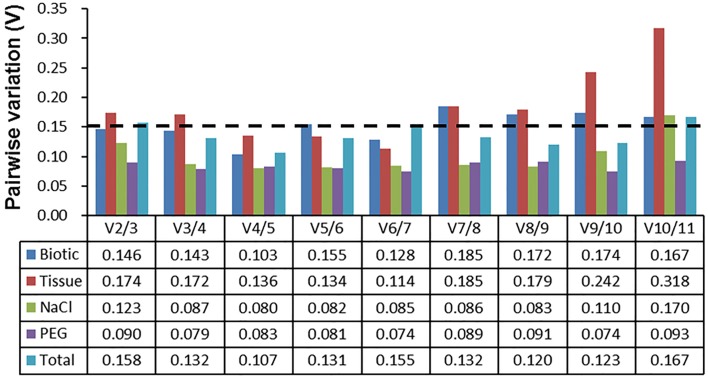

The pairwise variation (Vn) between normalization factors (NFn) calculated by the geNorm algorithm also determines the optimal number of reference genes for accurate normalization. A cut-off value of Vn∕n+1 < 0.15 (Vandesompele et al., 2002) indicates that an additional reference gene makes no significant contribution to the normalization. As depicted in Figure 3, the V2∕3 values in biotic stress, NaCl stress, and PEG stress subsets were below 0.15, which indicated that two reference genes (ACT7 and RAN for biotic subset; EF1α and RAN for NaCl subset; and EF1α and UBC for drought subset) were sufficient for accurate normalization. In the tissue subset, four reference genes (TUBβ, UBI, EF1α, and RAN) were needed for accurate normalization, as the V4∕5 value was lower than 0.15. When the total samples were taken into account, the V3/4 value (0.132) was lower than the cutoff value of 0.15, which indicated that three genes (ACT7, RAN, and DnaJ) were suitable for all samples in this study (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Determination of the optimal number of reference genes for normalization by pairwise variation (V) using geNorm. The pairwise variation (Vn/Vn+1) was calculated between normalization factors NFn and NFn+1 by geNorm to determine the optimal number of reference genes for qRT-PCR data normalization.

Stability analysis of reference genes by normfinder

The NormFinder approach was used to determine the stability of reference genes based on inter- and intra-group variance in expression. As shown in Table 2, similar results were generated by NormFinder, which predicted ACT7 and RAN to be the two most stably expressed normalization factors in both biotic and total subsets. For the NaCl and PEG treated samples, ACT7 and RAN performed as the best reference genes by the NormFinder analysis, while ACT7 was ranked the second in NaCl subset, and ACT7 and RAN the fifth and third in PEG subset by the geNorm analysis. For the tissue subset, the four most stable genes, TUBβ, EF1α, RAN, and UBI determined by NormFinder were ranked the first, second, third and first by geNorm algorithm, respectively (Table 2; Figure 2).

Table 2.

Expression stability of candidate reference genes as calculated by Normfinder.

| Rank | Biotic | Tissue | NaCl | PEG | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Stability | Gene | Stability | Gene | Stability | Gene | Stability | Gene | Stability | |

| 1 | RAN | 0.142 | TUBβ | 0.112 | ACT7 | 0.040 | RAN | 0.053 | RAN | 0.116 |

| 2 | ACT7 | 0.357 | EF1α | 0.126 | RAN | 0.167 | ACT7 | 0.173 | ACT7 | 0.262 |

| 3 | EF1α | 0.499 | RAN | 0.136 | UBQ | 0.190 | DnaJ | 0.206 | EF1α | 0.349 |

| 4 | DnaJ | 0.545 | UBI | 0.320 | EF1α | 0.236 | UBC | 0.262 | DnaJ | 0.410 |

| 5 | UBQ | 0.583 | ACT7 | 0.383 | TUBα | 0.325 | EF1α | 0.264 | UBQ | 0.487 |

| 6 | UBI | 0.650 | DnaJ | 0.603 | UBC | 0.366 | UBI | 0.292 | UBI | 0.492 |

| 7 | 18S rRNA | 0.734 | UBQ | 0.673 | DnaJ | 0.366 | TUBβ | 0.376 | TUBβ | 0.616 |

| 8 | TUBβ | 0.869 | UBC | 0.846 | TUBβ | 0.472 | UBQ | 0.404 | UBC | 0.660 |

| 9 | UBC | 0.882 | TUBα | 0.992 | UBI | 0.490 | TUBα | 0.543 | TUBα | 0.749 |

| 10 | TUBα | 1.079 | 18S rRNA | 1.882 | 18S rRNA | 0.744 | 18S rRNA | 0.557 | 18S rRNA | 0.830 |

| 11 | ACT | 1.257 | ACT | 2.409 | ACT | 1.288 | ACT | 0.702 | ACT | 1.262 |

Stability analysis of reference genes by bestkeeper

The BestKeeper program was used to evaluate the stabilities of reference genes based on the coefficient of variance (CV) and the standard deviation (SD) of the average Ct values. The most stable genes were identified as those that exhibit the lowest CV and SD (CV ± SD), and genes with SD greater than 1 were considered unacceptable and should be excluded (Chang et al., 2012; Xiao et al., 2014). In the biotic stress subset, 18S rRNA (2.96 ± 0.51) and UBI (2.39 ± 0.52) had lowest CV ± SD values, and showed remarkably stable expression. In the NaCl- and PEG-treated subset, TUBα had the lowest CV ± SD values of 0.79 ± 0.24 and 0.96 ± 0.29, respectively, and showed the most stable expression. In the total samples subset, UBI (2.32 ± 0.50) and 18S rRNA (3.76 ± 0.63) were identified as the two best reference genes for normalization. These results are inconsistent with those acquired from the geNorm and NormFinder methods (Figure 2; Tables 2, 3). In the tissue samples subset, the most stable reference genes identified by BestKeeper were UBI (1.98 ± 0.42) and TUBβ (2.03 ± 0.43). This result is consistent with the results obtained from geNorm and NormFinder analyses (Figure 2; Tables 2, 3).

Table 3.

Expression stability of candidate reference genes as calculated by BestKeeper.

| Rank | Biotic | Tissue | NaCl | PEG | Total | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | SD | CV | Gene | SD | CV | Gene | SD | CV | Gene | SD | CV | Gene | SD | CV | |

| 1 | 18S rRNA | 0.51 | 2.96 | UBI | 0.42 | 1.98 | TUBα | 0.24 | 0.79 | TUBα | 0.29 | 0.96 | UBI | 0.50 | 2.32 |

| 2 | UBI | 0.52 | 2.39 | TUBβ | 0.43 | 2.03 | UBC | 0.27 | 1.30 | DnaJ | 0.31 | 1.44 | 18S rRNA | 0.63 | 3.76 |

| 3 | ACT7 | 0.56 | 2.47 | DnaJ | 0.59 | 2.60 | UBI | 0.33 | 1.58 | UBC | 0.35 | 1.71 | DnaJ | 0.64 | 2.89 |

| 4 | DnaJ | 0.59 | 2.58 | RAN | 0.6 | 2.24 | RAN | 0.41 | 1.59 | UBI | 0.40 | 1.87 | ACT7 | 0.72 | 3.22 |

| 5 | RAN | 0.61 | 2.18 | UBQ | 0.65 | 3.23 | UBQ | 0.43 | 2.25 | 18S rRNA | 0.4 | 2.41 | EF1α | 0.72 | 3.92 |

| 6 | UBQ | 0.66 | 2.98 | UBC | 0.95 | 4.66 | EF1α | 0.44 | 2.41 | TUBβ | 0.41 | 1.86 | TUBβ | 0.78 | 3.48 |

| 7 | EF1α | 0.75 | 4.01 | TUBα | 0.97 | 4.11 | TUBβ | 0.47 | 2.09 | UBQ | 0.42 | 2.17 | UBC | 0.81 | 3.81 |

| 8 | ACT | 0.86 | 3.25 | EF1α | 1.00 | 5.70 | DnaJ | 0.48 | 2.18 | ACT | 0.43 | 1.68 | ACT | 0.94 | 3.64 |

| 9 | UBC | 1.06 | 4.79 | 18S rRNA | 1.03 | 6.28 | ACT7 | 0.55 | 2.48 | RAN | 0.48 | 1.87 | RAN | 1.15 | 4.35 |

| 10 | TUBα | 1.13 | 4.32 | ACT7 | 1.13 | 5.27 | 18S rRNA | 0.59 | 3.43 | ACT7 | 0.49 | 2.19 | UBQ | 1.32 | 6.54 |

| 11 | TUBβ | 1.17 | 5.04 | ACT | 1.50 | 6.37 | ACT | 0.81 | 3.15 | EF1α | 0.56 | 3.09 | TUBα | 2.66 | 9.37 |

Comprehensive stability analysis of reference genes

To acquire a consensus result of the best reference genes, three algorithms rankings of the stability were integrated, generating a comprehensive ranking according to the geometric mean of three rankings (Xiao et al., 2014). The comprehensive rankings were shown in Table 4: RAN and ACT7 were ranked as the top two stable reference genes in the biotic stress subset, NaCl stress subset and total samples subset; UBC and DnaJ were the two most stable genes in the PEG stress subset; TUBβ and UBI were the most stable genes, followed by EF1α and RAN in the tissue subset (Table 4). Taken the number of reference genes to use suggested by geNorm and the comprehensive rankings into consideration, the most stable and least stable combination of reference genes in each subset was shown in Table 5.

Table 4.

Expression stability ranking of the 11 candidate reference genes.

| Method | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) RANKING ORDER UNDER BIOTIC STRESS (BETTER-GOOD-AVERAGE) | |||||||||||

| NormFinder | RAN | ACT7 | EF1α | DnaJ | UBQ | UBI | 18S rRNA | TUBβ | UBC | TUBα | ACT |

| geNorm | ACT7/RAN | DnaJ | UBQ | EF1α | UBI | 18S rRNA | UBC | TUBβ | TUBα | ACT | |

| BestKeeper | 18S rRNA | UBI | ACT7 | DnaJ | RAN | UBQ | EF1α | ACT | UBC | TUBα | TUBβ |

| Comprehensive ranking | RAN | ACT7 | DnaJ | 18S rRNA | UBI | EF1α | UBQ | UBC | TUBβ | ACT | TUBα |

| (B) RANKING ORDER UNDER DIFFERENT TISSUES (BETTER-GOOD-AVERAGE) | |||||||||||

| NormFinder | TUBβ | EF1α | RAN | UBI | ACT7 | DnaJ | UBQ | UBC | TUBα | 18S rRNA | ACT |

| geNorm | TUBβ/UBI | EF1α | RAN | ACT7 | UBQ | DnaJ | UBC | TUBα | 18S rRNA | ACT | |

| BestKeeper | UBI | TUBβ | DnaJ | RAN | UBQ | UBC | TUBα | EF1α | 18S rRNA | ACT7 | ACT |

| Comprehensive ranking | TUBβ | UBI | EF1α | RAN | DnaJ | UBQ | ACT7 | UBC | TUBα | 18S rRNA | ACT |

| (C) RANKING ORDER UNDER NACL STRESS (BETTER-GOOD-AVERAGE) | |||||||||||

| NormFinder | ACT7 | RAN | UBQ | EF1α | TUBα | UBC | DnaJ | TUBβ | UBI | 18S rRNA | ACT |

| geNorm | EF1α/RAN | ACT7 | DnaJ | UBC | UBI | UBQ | TUBα | TUBβ | 18S rRNA | ACT | |

| BestKeeper | TUBα | UBC | UBI | RAN | UBQ | EF1α | TUBβ | DnaJ | ACT7 | 18S rRNA | ACT |

| Comprehensive ranking | RAN | ACT7 | EF1α | TUBα | UBC | UBQ | UBI | DnaJ | TUBβ | 18S rRNA | ACT |

| (D) RANKING ORDER UNDER PEG STRESS (BETTER-GOOD-AVERAGE) | |||||||||||

| NormFinder | RAN | ACT7 | DnaJ | UBC | EF1α | UBI | TUBβ | UBQ | TUBα | 18S rRNA | ACT |

| geNorm | EF1α/UBC | UBI | RAN | DnaJ | ACT7 | TUBβ | UBQ | TUBα | 18S rRNA | ACT | |

| BestKeeper | TUBα | DnaJ | UBC | UBI | 18S rRNA | TUBβ | UBQ | ACT | RAN | ACT7 | EF1α |

| Comprehensive ranking | UBC | DnaJ | RAN | UBI | EF1α | TUBα | ACT7 | TUBβ | UBQ | 18S rRNA | ACT |

| (E) RANKING ORDER UNDER TOTAL SAMPLES (BETTER-GOOD-AVERAGE) | |||||||||||

| NormFinder | RAN | ACT7 | EF1α | DnaJ | UBQ | UBI | TUBβ | UBC | TUBα | 18S rRNA | ACT |

| geNorm | ACT7/RAN | DnaJ | UBQ | EF1α | UBI | UBC | TUBβ | 18S rRNA | TUBα | ACT | |

| BestKeeper | UBI | 18S rRNA | DnaJ | ACT7 | EF1α | TUBβ | UBC | ACT | RAN | UBQ | TUBα |

| Comprehensive ranking | ACT7 | RAN | DnaJ | UBI | EF1α | UBQ | 18S rRNA | TUBβ | UBC | ACT | TUBα |

Table 5.

Best combination of reference genes based on the geNorm and comprehensive rankings in each subset.

| Biotic | Tissue | NaCl | PEG | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most | Least | Most | Least | Most | Least | Most | Least | Most | Least |

| RAN | TUBα | TUBβ | ACT | RAN | ACT | UBC | ACT | ACT7 | TUBα |

| ACT7 | UBI | ACT7 | DnaJ | RAN | |||||

| EF1α | DnaJ | ||||||||

| RAN | |||||||||

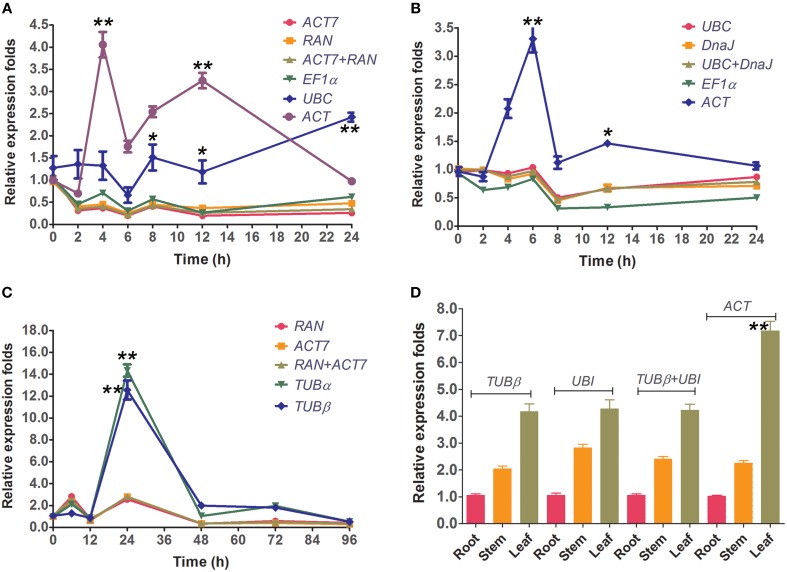

Reference genes validation

To validate the selected reference genes, the relative expression levels of the target gene, CcWRKY15 under different experimental conditions were evaluated using qRT-PCR. CcWRKY15 is a homolog of AtWRKY15, which is known to be a central regulator in the response to oxidative stress and pathogenic infection (Vanderauwera et al., 2012). Thus, it would be expected to have similar expression patterns as AtWRKY15 under abiotic and biotic stress conditions. However, a substantial divergence can occur in its relative transcript abundance when normalized to different kinds of reference genes. We therefore used the most stable reference genes found in each subset (ACT7 and RAN for Biotic stress and NaCl stress; UBC and DnaJ for PEG stress) either singly or in combination, and the least stable reference gene (ACT or TUBα), to perform a qRT-PCR analysis. Results showed that in accordance with the behavior of AtWRKY15 previously described in A. thaliana, the CcWRKY15 functions as a negative regulator and was induced by salt-stress, oxidative-stress, and pathogenic infections (C. siamense) in jute (Figure 4). In addition, we also examined the reference gene (EF1α and UBC for abiotic stress; TUBβ for fungal stress) selected by Ferdou et al. (2015) in NaCl stress, PEG stress, and fungal stress subsets. The results showed that EF1α could sever as a stable reference gene for normalization but UBC unstable under NaCl stress condition (Figure 4A). For the PEG stress subset, the relative expression folds of CcWRKY15 normalized by EF1α were slightly decreased compared to the stable genes UBC and DnaJ (Figure 4B). For the biotic stress subset, reference gene TUBβ was not as stable as that described by Ferdou et al. (2015), conversely, similar to the expression pattern of the worst gene TUBα (Figure 4C). Our tissue type analysis revealed that the transcript abundance of CcWRKY15 was the highest in the leaf, followed by the stem and then the root (p < 0.01) (Figure 4D). Contrastingly, when the least stable reference gene was used as normalization factor, the expression level of CcWRKY15 was significantly overestimated (p < 0.01). For example, the relative expression folds of CcWRKY15 were approximately eight-fold (p < 0.01) higher than that of ACT7, RAN, or their combination at 4 h under NaCl stress, when ACT was used as normalization factor (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Relative quantification of CcWRKY15 expression using the validated reference gene(s). The results are represented as mean fold changes in relative expression when compared to the first sampling stage (0 h). cDNA samples were taken from the same subset used for gene expression stability analysis. (A,B) Leaves were collected from 3-week-old seedlings subjected to salt- and PEG-stress after 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h of treatment. (C) Leaves were collected from 3-week-old seedlings subjected to biotic stress (C. siamense) after 0, 6, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h of treatment. (D) Different tissue types were collected from 3-week-old seedlings. * indicates statistically significant (p < 0.05); ** indicates greatly statistically significant (p < 0.01).

Discussion

There has been a surge in interest for environment-friendly materials and jute fiber—used as reinforcement component—has been widely used in the textile, papermaking, automotive, and aerospace industries. Given its popularity, the need for the application of new genomic tools has become increasingly important (Sydenstricker et al., 2003; Corrales et al., 2007). New technologies such as qRT-PCR now make it possible to understand the molecular mechanisms underpinning the commercially important traits of jute. qRT-PCR is an essential tool that can be used in studies of target gene expression patterns. Although past studies have used 18S rRNA as a reference gene for examining the functions of UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase and caffeoyl-CoA 3-O-methyltransferase in jute (C. capsularis) (Zhang et al., 2013, 2014), and in the most recent study were 7 reference genes tested under abiotic and biotic stress in the other jute species Corchorus olitorius (Ferdou et al., 2015), little information is available on the systematic exploration and validation of a set of suitable reference genes in jute (C. capsularis). In addition, it has been reported that ribosomal RNA genes are not adequate reference genes due to their high transcription abundance. Ultimately, this could lead to experimental error when normalizing genes with weak expression (Jain et al., 2006; Niu et al., 2014). Comparing our results to that of Ferdou et al. (2015), the stability values of three out of seven reference genes (EF1α and UBC for abiotic stress; TUBβ for biotic stress) were significantly lower in our experiment. For instance, when UBC was used as reference gene, CcWRKY15 had a 5.0-fold higher expression value at 24 h under NaCl stress condition (Figure 4A); when TUBβ as an internal reference, CcWRKY15 had a 6.0 times higher at 24 h after inoculation (Figure 4C). Additionally, TUBβ was found to be one of the least stable genes in our study. These expression stability differences might be a result of different species/cultivars analyzed in the compared experiment conditions. It is consistent with the previous studies that the stability of reference genes is not only cultivar/species specific but may also be tissue specific and influenced by the different experimental treatments (Nicot et al., 2005; Štajner et al., 2013; Zhuang et al., 2015). This is also the primary reason for validating the stability of reference genes for a specific genotype and/or experimental treatment.

In this study, we used three publicly available programs, geNorm (Vandesompele et al., 2002), NormFinder (Andersen et al., 2004), and BestKeeper (Pfaffl et al., 2004), to evaluate the expression stability of 11 candidate reference genes in a total of 25 jute samples taken from different tissues and experimental treatment groups. We found different rankings for the selected genes after comparison to the ranking of the candidates generated by the three algorithms (Figure 2; Tables 2, 3). This apparent divergence probably reflects the discrepancies in the three statistical algorithms to calculate stability. NormFinder takes the inter- and intra-group variations into account, and combines them into a stability value, and finally ranks the top genes with minimal inter- and intra-group variation. In contrast, geNorm identifies two reference genes with the highest degree of similarity in expression profile and the lowest intra-group variation (Andersen et al., 2004; Jian et al., 2008; Cruz et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2012). As for BestKeeper, this program determines the stability ranking of the reference genes based on the coefficient of variance (CV) and the standard deviation (SD) values. The most stable genes are identified as those that exhibit the lowest CV ± SD values (Chang et al., 2012; Xiao et al., 2014). Similar methods have been used in previous studies of different species, such as Salicornia europaea (Huang et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2014), Populus euphratica (Wang et al., 2014), and Cynodon dactylon (Chen et al., 2014). Thus, referring to the previous studies (Štajner et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2014), the integrated results were obtained from three programs, leading to a more comprehensive ranking and better accuracy for each gene (Table 4).

Of the top three reference genes defined by three algorithms in the total samples subset, ACT7 and RAN were found to be the best candidates for the biotic stress and NaCl stress subsets. The strong performance of ACT7 in jute (C. capsularis) was consistent with the results obtained in the developmental stage series of G. max (Jian et al., 2008), during grape berry development of V. vinifera (Reid et al., 2006), and across different tissues and cold-treated samples of Platycladus orientalis (Chang et al., 2012). However, this gene performed poorly in studies of O. sativa (Jain et al., 2006), S. officinarum (Ling et al., 2014), and S. tuberosum (Nicot et al., 2005), suggesting that the expression levels of reference genes are variable among different species. RAN was the other most stable reference gene found in the present study. It has also been shown to be the best performer across different tissue and hormone treatment samples of M. acuminata (Chen et al., 2011) as well as in the leaf or plant growth regulator treatment samples of C. melo (Kong et al., 2014). DnaJ showed relatively stable expression and ranked third across all samples (Figure 2; Tables 3, 4). This gene has also been recommended as the best reference gene in different tissues and NaCl-treated samples of P. orientalis (Chang et al., 2012).

However, the data presented show that the candidate reference genes EF1α, UBC, UBI, UBQ, and TUBβ were moderately expressed and had variable rankings in this study. For example, EF1α was ranked first by geNorm analysis and was stably expressed in NaCl- and PEG-treated samples, but was shown to be the fourth in NaCl stress subset analyzed by NormFinder; the fifth in PEG stress subset by NormFinder and Comprehensive ranking. Previously, EF1α showed stable expression during abiotic and biotic stress in O. sativa (Jain et al., 2006), L. chinensis (Zhong et al., 2011), S. tuberosum (Nicot et al., 2005), and C. sativus (Wan et al., 2010), but was shown as an unsatisfactory reference gene in T. aestivum (Paolacci et al., 2009), G. max (Jian et al., 2008), N. benthamiana (Liu et al., 2012), and P. orientalis (Chang et al., 2012). UBC, an ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme gene, was ranked first in the PEG stress subset, which was also the optimal reference gene under NaCl- and PEG-treated conditions in P. orientalis (Chang et al., 2012) and C. olitorius (Ferdou et al., 2015); however, it was not the best choice for normalization in the different tissues of bamboo (Fan et al., 2013). UBQ were relatively weakly expressed across all the experimental samples according to the three programs and comprehensive analyses, but were the optimal reference genes for developmental stages and under NaCl- and PEG-treated conditions in P. orientalis (Chang et al., 2012). As previously noted, TUBβ was the most stable reference gene across various developmental stages of G. max (Jian et al., 2008), leaf senescence system of H. annuus (Fernandez et al., 2011), and among different tissues and PEG-treated samples of P. orientalis (Chang et al., 2012). In this study, similarly, all of the algorithms ranked TUBβ in the first position, indicating that TUBβ was the optimal choice as an internal control gene for different tissues investigated in jute (C. capsularis). UBI, another stable reference gene, showed relatively small variation in tissues subset, which was also the most stable reference gene in different tissues of C. sativus (Wan et al., 2010). In different tissues subset, in addition to expression of TUBβ and UBI, the expression of EF1α and RAN was also stable and therefore they were considered as the suitable reference genes (Figure 2; Table 4).

Interestingly, the commonly used reference genes TUBα, 18S rRNA, and ACT performed poorly and were not suitable for most of the experimental conditions. Several studies have shown similar results. For example, TUBα was found to be unstable as reference gene in the developmental stage in tomato (Expósito-Rodríguez et al., 2008) and in different flax tissue (Huis et al., 2010). 18S rRNA was considered as the least reliable reference gene in viral-infected N. benthamiana (Liu et al., 2012) and under different conditions in C. sativus (Wan et al., 2010). ACT was proved unsuitable for normalization in different flax tissues (Huis et al., 2010), during abiotic and biotic stress in S. tuberosum (Nicot et al., 2005), and in viral-infected N. benthamiana (Liu et al., 2012). Taken together, these findings indicate that large numbers of experimental data on gene expression should be acquired to investigate the transcript stability of commonly used reference genes under different experimental conditions.

To further validate the feasibility of the reference genes screened in this study, we analyzed the transcription profiles of the WRKY domain gene CcWRKY15, a homolog AtWRKY15 of A. thaliana. AtWRKY15 has been shown to be a key regulator of plant growth and salt/osmotic stress responses in A. thaliana (Vanderauwera et al., 2012). In this study, the expression of CcWRKY15 was normalized using the most stable reference genes in each subset both singly and combined as well as a least stable gene as an internal control (Figure 4). Our results showed that expression of CcWRKY15 was negatively induced by NaCl- and PEG-treated stress (Figures 4A,B) and was significantly increased after 24 h of inoculation treatment (Figure 4C) (p < 0.01). By comparing the expression pattern of CcWRKY15 with that reported in A. thaliana (Vanderauwera et al., 2012), a supported result was found. Therefore, the results obtained from this study are credible. Moreover, we compared the results from the jute species C. olitorius selected by Ferdou et al. (2015) under the same conditions, the results showed great differences between them. These results underscore the fact that inappropriate utilization of reference genes without validation may generate bias in the analysis and lead to misinterpretation of qRT-PCR data.

Conclusion

We present here a systematic attempt to validate a set of candidate reference genes for the normalization of gene expression using qRT-PCR in jute (C. capsularis) under abiotic (salt and drought) and biotic (Colletotrichum siamense) stress conditions as well as across different tissue types. The expression stability of the 11 candidates was analyzed by the three applications (geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper), and their results were furtherly integrated into a comprehensive ranking based on the geometric mean. For gene expression study under biotic stress and NaCl stress, we recommend ACT7 and RAN to normalize the qRT-PCR data. For gene expression study under PEG stress, UBC, and DnaJ are the two most suitable reference genes in C. capsularis. For the study of gene expression in the different tissues, TUBβ, UBI, EF1α, and RAN are recommended as the best reference genes for normalization. In addition, the two least stable reference genes 18S rRNA and ACT should be carefully used for normalization. Furthermore, the feasibility of the reference genes screened was further confirmed by comparing the expression pattern between CcWRKY15 and AtWRKT15, and the selected reference genes can perform significantly better in gene expression normalization. In particular, the reference genes selected in current study will facilitate the future work on gene expression studies in C. capsularis.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the 948 project of the Agricultural Department of China (2013–Z70), the National Bast Fiber Germplasm Resources Project of China (K47NI201A), the National Bast Fiber Research System of China (CARS–19–E06), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31471549).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2015.00848

References

- Alam M. M., Sharmin S., Nabi Z., Mondal S. I., Islam M. S., Bin Nayeem S., et al. (2010). A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase of jute involved in stress response. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 28, 394–402. 10.1007/s11105-009-0166-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen C. L., Jensen J. L., Ørntoft T. F. (2004). Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: a model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 64, 5245–5250. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artico S., Nardeli S. M., Brilhante O., Grossi-de-Sa M. F., Alves-Ferreira M. (2010). Identification and evaluation of new reference genes in Gossypium hirsutum for accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data. BMC Plant Biol. 10:49. 10.1186/1471-2229-10-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A., Ghosh M., Meyer R., Powell W., Basak S. L., Sen S. K. (2004). Analysis of genetic diversity in cultivated jute determined by means of SSR markers and AFLP profiling. Crop Sci. 44, 678–685. 10.2135/cropsci2004.6780 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bustin S. A. (2002). Quantification of mRNA using real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR): trends and problems. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 29, 23–39. 10.1677/jme.0.0290023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E., Shi S., Liu J., Cheng T., Xue L., Yang X., et al. (2012). Selection of reference genes for quantitative gene expression studies in Platycladus orientalis (Cupressaceae) Using real-time PCR. PLoS ONE 7:e33278. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay T., Roy S., Mitra A., Maiti M. K. (2011). Development of a transgenic hairy root system in jute (Corchorus capsularis L.) with gusA reporter gene through Agrobacterium rhizogenes mediated co-transformation. Plant Cell Rep. 30, 485–493. 10.1007/s00299-010-0957-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Zhong H. Y., Kuang J. F., Li J. G., Lu W. J., Chen J. Y. (2011). Validation of reference genes for RT-qPCR studies of gene expression in banana fruit under different experimental conditions. Planta 234, 377–390. 10.1007/s00425-011-1410-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Tan Z., Hu B., Yang Z., Xu B., Zhuang L., et al. (2014). Selection and validation of reference genes for target gene analysis with quantitative RT-PCR in leaves and roots of bermudagrass under four different abiotic stresses. Physiol Plant. 10.1111/ppl.12302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrales F., Vilaseca F., Llop M., Girones J., Méndez J. A., Mutje P. (2007). Chemical modification of jute fibers for the production of green-composites. J. Hazard. Mater. 144, 730–735. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.01.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz F., Kalaoun S., Nobile P., Colombo C., Almeida J., Barros L. M. G., et al. (2009). Evaluation of coffee reference genes for relative expression studies by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Mol. Breed. 23, 607–616. 10.1007/s11032-009-9259-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Czechowski T., Stitt M., Altmann T., Udvardi M. K., Scheible W. R. (2005). Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 139, 5–17. 10.1104/pp.105.063743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defoirdt N., Biswas S., De Vriese L., Tran L. Q. N., van Acker J., Ahsan Q., et al. (2010). Assessment of the tensile properties of coir, bamboo and jute fibre. Comp. A 41, 588–595. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2010.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- del Río J. C., Rencoret J., Marques G., Li J., Gellerstedt G., Jimenez-Barbero J., et al. (2009). Structural characterization of the lignin from jute (Corchorus capsularis) Fibers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 10271–10281. 10.1021/jf900815x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expósito-Rodríguez M., Borges A. A., Borges-Pérez A., Pérez J. A. (2008). Selection of internal control genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR studies during tomato development process. BMC Plant Biol. 8:131. 10.1186/1471-2229-8-131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C., Ma J., Guo Q., Li X., Wang H., Lu M. (2013). Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). PLoS ONE 8:e56573. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdou A. S., Islam M. T., Alam S. S., Khan H. (2015). Identification of stable reference gene for quantitative PCR in jute under different experimental conditions: an essential assessment for gene expression analysis. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 9, 646–655. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez P., Di Rienzo J. A., Moschen S., Dosio G. A., Aguirrezábal L. A., Hopp H. E., et al. (2011). Comparison of predictive methods and biological validation for qPCR reference genes in sunflower leaf senescence transcript analysis. Plant Cell Rep. 30, 63–74. 10.1007/s00299-010-0944-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez L., Mauriat M., Guénin S., Pelloux J., Lefebvre J. F., Louvet R., et al. (2008). The lack of a systematic validation of reference genes: a serious pitfall undervalued in reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis in plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 6, 609–618. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00346.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Yan H., Jiang X., Yin G., Zhang X., Qi X., et al. (2014). Identification of candidate reference genes in perennial ryegrass for quantitative RT-PCR under various abiotic stress conditions. PLoS ONE 9:e93724. 10.1371/journal.pone.0093724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggett J., Dheda K., Bustin S., Zumla A. (2005). Real-time RT-PCR normalisation; strategies and considerations. Genes Immun. 6, 279–284. 10.1038/sj.gene.6364190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huis R., Hawkins S., Neutelings G. (2010). Selection of reference genes for quantitative gene expression normalization in flax (Linum usitatissimum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 10:71. 10.1186/1471-2229-10-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T., Ubi B. E., Saito T., Moriguchi T. (2014). Evaluation of reference genes for accurate normalization of gene expression for real time-quantitative PCR in Pyrus pyrifolia using different tissue samples and seasonal conditions. PLoS ONE 9:e86492. 10.1371/journal.pone.0086492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M., Nijhawan A., Tyagi A. K., Khurana J. P. (2006). Validation of housekeeping genes as internal control for studying gene expression in rice by quantitative real-time PCR. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 345, 646–651. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian B., Liu B., Bi Y., Hou W., Wu C., Han T. (2008). Validation of internal control for gene expression study in soybean by quantitative real-time PCR. BMC Mol. Biol. 9:59. 10.1186/1471-2199-9-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Q., Yuan J., Niu P., Xie J., Jiang W., Huang Y., et al. (2014). Screening suitable reference genes for normalization in reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR analysis in melon. PLoS ONE 9:e87197. 10.1371/journal.pone.0087197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libault M., Thibivilliers S., Bilgin D. D., Radwan O., Benitez M., Clough S. J., et al. (2008). Identification of four soybean reference genes for gene expression normalization. Plant Genome J. 1, 44 10.3835/plantgenome2008.02.0091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Han X., Chen Y., Wu Q., Wang Y. (2013). Identification of appropriate reference genes for normalizing transcript expression by quantitative real-time PCR in Litsea cubeba. Mol. Genet. Genomics 288, 727–737. 10.1007/s00438-013-0785-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H., Wu Q., Guo J., Xu L., Que Y. (2014). Comprehensive selection of reference genes for gene expression normalization in sugarcane by real time quantitative rt-PCR. PLoS ONE 9:e97469. 10.1371/journal.pone.0097469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Shi L., Han C., Yu J., Li D., Zhang Y. (2012). Validation of reference genes for gene expression studies in virus-infected Nicotiana benthamiana using quantitative real-time PCR. PLoS ONE 7:e46451. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long X. Y., Wang J. R., Ouellet T., Rocheleau H., Wei Y. M., Pu Z. E., et al. (2010). Genome-wide identification and evaluation of novel internal control genes for Q-PCR based transcript normalization in wheat. Plant Mol. Biol. 74, 307–311. 10.1007/s11103-010-9666-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B. C., Tang W. L., Ma L. Y., Li L. L., Zhang L. B., Zhu S. J., et al. (2009). The role of chitinase gene expression in the defense of harvested banana against anthracnose disease. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 134, 379–386. [Google Scholar]

- Mafra V., Kubo K. S., Alves-Ferreira M., Ribeiro-Alves M., Stuart R. M., Boava L. P., et al. (2012). Reference genes for accurate transcript normalization in citrus genotypes under different experimental conditions. PLoS ONE 7:e31263. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mir R. R., Banerjee S., Das M., Gupta V., Tyagi A. K., Sinha M. K., et al. (2009). Development and characterization of large-scale simple sequence repeats in jute. Crop Sci. 49, 1687–1694. 10.2135/cropsci2008.10.0599 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mir R. R., Rustgi S., Sharma S., Singh R., Goyal A., Kumar J., et al. (2008). A preliminary genetic analysis of fibre traits and the use of new genomic SSRs for genetic diversity in jute. Euphytica 161, 413–427. 10.1007/s10681-007-9597-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narsai R., Ivanova A., Ng S., Whelan J. (2010). Defining reference genes in Oryza sativa using organ, development, biotic and abiotic transcriptome datasets. BMC Plant Biol. 10:56. 10.1186/1471-2229-10-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicot N., Hausman J. F., Hoffmann L., Evers D. (2005). Housekeeping gene selection for real-time RT-PCR normalization in potato during biotic and abiotic stress. J. Exp. Bot. 56, 2907–2914. 10.1093/jxb/eri285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu J., Zhu B., Cai J., Li P., Wang L., Dai H., et al. (2014). Selection of reference genes for gene expression studies in Siberian Apricot (Prunus sibirica L.) Germplasm using quantitative real-time PCR. PLoS ONE 9:e103900. 10.1371/journal.pone.0103900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksman K., Skrifvars M., Selin J. F. (2003). Natural fibres as reinforcement in polylactic acid (PLA) composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 63, 1317–1324. 10.1016/S0266-3538(03)00103-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paolacci A. R., Tanzarella O. A., Porceddu E., Ciaffi M. (2009). Identification and validation of reference genes for quantitative RT-PCR normalization in wheat. BMC Mol. Biol. 10:11. 10.1186/1471-2199-10-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W., Tichopad A., Prgomet C., Neuvians T. P. (2004). Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: bestKeeper–Excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol. Lett. 26, 509–515. 10.1023/B:BILE.0000019559.84305.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi J. M., Zhou D. X., Wu W. R., Lin L. H., Fang P. P., Wu J. M. (2003b). The application of RAPD technology in genetic diversity detection of Jute. Yi Chuan Xue Bao 30, 926–932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi J., Zhou D., Wu W., Lin L., Wu J., Fang P. (2003a). Application of ISSR technology in genetic diversity detection of jute. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao 14, 1473–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid K. E., Olsson N., Schlosser J., Peng F., Lund S. T. (2006). An optimized grapevine RNA isolation procedure and statistical determination of reference genes for real-time RT-PCR during berry development. BMC Plant Biol. 6:27. 10.1186/1471-2229-6-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remans T., Smeets K., Opdenakker K., Mathijsen D., Vangronsveld J., Cuypers A. (2008). Normalisation of real-time RT-PCR gene expression measurements in Arabidopsis thaliana exposed to increased metal concentrations. Planta 227, 1343–1349. 10.1007/s00425-008-0706-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy A., Bandyopadhyay A., Mahapatra A. K., Ghosh S. K., Singh N. K., Bansal K. C., et al. (2006). Evaluation of genetic diversity in jute (Corchorus species) using STMS, ISSR and RAPD markers. Plant Breeding 125, 292–297. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2006.01208.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt G. W., Delaney S. K. (2010). Stable internal reference genes for normalization of real-time RT-PCR in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) during development and abiotic stress. Mol. Genet. Genomics 283, 233–241. 10.1007/s00438-010-0511-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Štajner N., Cregeen S., Javornik B. (2013). Evaluation of reference genes for RT-qPCR expression studies in hop (Humulus lupulus L.) during infection with vascular pathogen verticillium albo-atrum. PLoS ONE 8:e68228. 10.1371/journal.pone.0068228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sydenstricker T. H. D., Mochnaz S., Amico S. C. (2003). Pull-out and other evaluations in sisal-reinforced polyester biocomposites. Polym. Test. 22, 375–380. 10.1016/S0142-9418(02)00116-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderauwera S., Vandenbroucke K., Inzé A., van de Cotte B., Mühlenbock P., De Rycke R., et al. (2012). AtWRKY15 perturbation abolishes the mitochondrial stress response that steers osmotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 20113–20118. 10.1073/pnas.1217516109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J., De Preter K., Pattyn F., Poppe B., Van Roy N., De Paepe A., et al. (2002). Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 3:research0034.1–0034.11. 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan H., Zhao Z., Qian C., Sui Y., Malik A. A., Chen J. (2010). Selection of appropriate reference genes for gene expression studies by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction in cucumber. Anal. Biochem. 399, 257–261. 10.1016/j.ab.2009.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. L., Chen J. H., Tian Q., Wang S., Xia X. L., Yin W. L. (2014). Identification and validation of reference genes for Populus euphratica gene expression analysis during abiotic stresses by quantitative real-time PCR. Physiol. Plant. 152, 529–545. 10.1111/ppl.12206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X., Ma J., Wang J., Wu X., Li P., Yao Y. (2014). Validation of suitable reference genes for gene expression analysis in the halophyte Salicornia europaea by real-time quantitative PCR. Front. Plant Sci. 5:788. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Qi J., Xu J., Niu X., Zhang Y., Tao A., et al. (2013). Overexpression of UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase gene could increase cellulose content in Jute (Corchorus capsularis L.). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 442, 153–158. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.11.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Zhang Y., Xu J., Niu X., Qi J., Tao A., et al. (2014). The CCoAOMT1 gene from jute (Corchorus capsularis L.) is involved in lignin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Gene 546, 398–402. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H. Y., Chen J. W., Li C. Q., Chen L., Wu J. Y., Chen J. Y., et al. (2011). Selection of reliable reference genes for expression studies by reverse transcription quantitative real-time PCR in litchi under different experimental conditions. Plant Cell Rep. 30, 641–653. 10.1007/s00299-010-0992-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang H., Fu Y., He W., Wang L., Wei Y. (2015). Selection of appropriate reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in Oxytropis ochrocephala Bunge using transcriptome datasets under abiotic stress treatments. Front. Plant Sci. 6:475. 10.3389/fpls.2015.00475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.