Abstract

Bacterial proteomic studies frequently use strains cultured in synthetic liquid media over many generations. It is uncertain whether bacterial proteins expressed under these conditions will be the same as the repertoire found in natural environments, or when bacteria are infecting a host organism. Thus, genomic and proteomic characterization of bacteria derived from the host environment in comparison to reference strains grown in the lab, should aid understanding of pathogenesis. Isolates of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis were obtained from the lymph nodes of three naturally infected sheep and compared to a laboratory reference strain using bottom-up proteomics, after whole genome sequencing of each of the field isolates. These comparisons were performed following growth in liquid media that allowed us to reach the required protein amount for proteomic analysis. Over 1350 proteins were identified in the isolated strains, from which unique proteome features were revealed. Several of the identified proteins demonstrated a significant abundance difference in the field isolates compared to the reference strain even though there were no obvious differences in the DNA sequence of the corresponding gene or in nearby non-coding DNA. Higher abundance in the field isolates was observed for proteins related to hypoxia and nutrient deficiency responses as well as to thiopeptide biosynthesis.

Keywords: natural infection, Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, dimethylation labeling, bacterial response to host, lymph nodes, thiopeptide, carbon starvation protein A, lactate utilization

Introduction

Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis caseous lymphadenopathy and wasting in sheep and goats (Dorella et al., 2006) resulting in significant mortality and morbidity as well as economic costs to livestock (Bush et al., 2012). Human cases of C. pseudotuberculosis infection are rare but well documented (Peel et al., 1997; Trost et al., 2010) and have similar clinical features and pathology.

After inoculation through a skin wound C. pseudotuberculosis establishes a chronic caseating infection in the lymph nodes of its animal hosts (Baird and Fontaine, 2007; Fontaine and Baird, 2008). This space is rich in immune cells and necrotic material, which contains degradative enzymes and cellular waste products. C. pseudotuberculosis and related species are known to utilize both carbohydrate and lipid carbon sources for growth (Inui et al., 2004), and have the capacity to switch between these metabolic pathways depending on substrate availability (Woo et al., 2010). Bacterial cells exposed to this hostile environment may counter this by modifying the proteins expressed on their surface (Rees et al., 2015). It is likely that longer term exposure to such conditions will modify the expression of different groups of proteins throughout the whole bacterial proteome, and proteome differences have been noted in direct comparisons between bacteria isolated from the host and media (Weigoldt et al., 2011). However, it is not clear whether this would occur from changes in the genome or the regulation of protein transcription (Güell et al., 2011).

The repertoire of proteins expressed by an organism will differ depending on the cell's growth phase and surrounding environment. The host environment presents specific challenges to a pathogen that includes both targeted attack from the host immune system and general stressors which arise from the physical milieu of the host cells in which the bacteria reside such as hypoxia, acidosis and paucity of nutrients.

We set out to determine if the protein repertoire of bacteria recently isolated from the host after a sustained infection differed from that of cells that had been passaged through a liquid media environment. To do this we compared their genomes and utilized quantitative proteomics to compare abundance of individual protein species when growing in common culture media.

Materials and methods

Collection of bacterial isolates

Three field isolates of C. pseudotuberculosis were obtained and are detailed in Table 1. Specimens of macroscopically infected lymph nodes from three separate randomly selected sheep were obtained from a local abattoir (Herd Abattoir, Geelong). Infected caseous material from the lymph nodes were streaked onto BHI agar plates and an individual colony of bacteria was selected for subculture and sequencing. C. pseudotuberculosis was grown in BHI media aerobically at 37°C, with continuous shaking. Growth of bacteria in liquid media was measured by determining cell mass with optical densitometry (OD 400 nanometers).

Table 1.

Summary of isolates investigated with details of whole genome sequencing approaches used and results, including sequencing approach, and genome assembly.

| Sequencing statistics | Bacterial isolate sequenced | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cptb_RLC_001 | Cptb_RLC_002 | Cptb_RLC003 | Cptb_C231 | |

| Sequencing instrument | Ion torrent | MiSeq | MiSeq | MiSeq |

| Number of contig | 42 | 27 | 57 | |

| Total contig length (bp) | 2231996 | 2323242 | 2317599 | |

| Minimum contig length (bp) | 221 | 321 | 287 | |

| Average contig length (bp) | 53142 | 86046 | 40659 | |

| Maximum Contig Length (bp) | 333978 | 385019 | 152746 | |

| N50 (bp) | 205882 | 235822 | 78603 | |

| Reads | 3507459 | |||

| Mean length (bp) | 183 | |||

| Assembly type | Scaffold | De novo | De novo | De novo |

Contig, Continous set of overlapping DNA; bp, base pairs.

A laboratory reference strain of C. pseudotuberculosis C231 (Cptb_C231; Burrell, 1978; Ruiz et al., 2011) was obtained from Dr Rob Moore, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Geelong, Australia. This strain was isolated more than 30 years ago and had been only passaged in liquid BHI over this time.

Whole genome sequencing

Genomic DNA extraction was performed with the Nucleon Kit (Amersham Biosciences), and this method generally followed the manufacturer's instructions. Specifically, C. pseudotuberculosis grown on BHI Agar plates without antibiotics and were disrupted with acid washed glass beads by bead beater (Fastprep, MP Biomedicals), in the presence of RNase and Proteinase K. Genomic DNA was separated from proteins by suspension in sodium percholate and chloroform prior to precipitation in Nucleon resin. Genomic DNA was secondarily precipitated with 100% ethanol prior to final re-suspension in water.

For the first field isolate Cptb_RLC001 high throughput sequencing was performed on this genomic material using the Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine (Life Technologies, Guilford, CT, USA) with a 316 chip and 200 bp sequencing chemistry. The sequence reads were mapped to the C. pseudotuberculosis C231 reference genome using SHRiMP 2.2 (Rumble et al., 2009). SNPs were identified using Nesoni v0.70, to construct a tally of putative differences at each position that included substitution mutations only (www.vicbioinformatics.com).

Genome sequences for isolates (Cptb_RLC002 and RLC003) were obtained using an Illumina MiSeq with Nextera XP library preparation and 2 × 300 bp sequencing chemistry to approximately 200x read coverage. We also sequenced our version of the C. pseudotuberculosis C231 reference (GenBank reference NC_017301). Resulting DNA sequence reads and existing sequence reads for Cptb_RLC001 were analyzed as previously described (Rees et al., 2015) to define a core genome by aligning reads to the 2,328,208 bp C321 reference chromosome. A genome for each isolate sequenced using Illumina chemistry was partially assembled de novo using Velvet v1.20.10 (PMID:18349386), with the resulting contigs annotated with Prokka v1.10 (PMID:24642063). The accessory genome for each of the isolates was explored using Fripan (http://drpowell.github.io/FriPan/) with ortholog clustering inputs obtained from Proteinortho5 (PMID: 21526987) with the following match parameters, expect score = 1e-09, identity = 80%, coverage = 30%. The translated protein coding DNA sequences predicted by Prokka were used as inputs to Proteinortho5.

Whole proteome extraction

Cultures of C. pseudotuberculosis (both reference strain Cptb_C231 and three field isolates Cptb_RLC001, Cptb_RLC002, Cptb_RLC003) were grown in BHI liquid media with shaking until late exponential phase (OD = 15) then washed three times with PBS and pelleted, resulting in a final volume of packed cells of 100 μl, these were then frozen at −80°C until required.

Whole Proteome Extracts were Prepared by Two Methods.

Firstly, unlabeled samples were prepared for label free quantitative analysis using the FASP method adapted from Wisniewski (Wiśniewski et al., 2009) with some modifications. Specifically 100 μl of washed and packed bacterial cells were freeze thawed then suspended in three times volume lysis buffer (4% SDS with 100 mM Tris plus 100 mM DTT) and heated to 95°C for 5 min. Samples were sonicated for 5 min and cellular debris was precipitated. Proteins were quantified by Bradford assay (Bradform Ultra, Expedion). Then 100 μg of bacterial lysate were combined with 8 M Urea in 100 mM Tris-HCl, (total volume 200 μL) loaded on 30 kD ultrafiltration device (Millipore) and centrifuged at 14,000xg for 15 min, a further 200 μL of 8 M Urea in 100 mM Tris-HCl was added and centrifuged at 14,000xg and this was repeated. Then 100 μL of 0.05 M iodoacetamide in 8 M Urea in 100 mM Tris-HCl was added and incubated for 20 min prior to centrifugation and washing with 8 M Urea in 100 mM Tris-HCl. The sample then underwent overnight digestion with trypsin and the digests were collected in 75 μL of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate by centrifugation and the filter device rinsed with 50 μL 0.5 M NaCl and centrifuged. The filtrate now contains the digested peptides and this solution was acidified to pH 2 with formic acid.

Desalting and concentration of peptides in solution was performed with bench-top columns [TopTip™ Reversed Phase (C-18), Glygen] prior to loading for HPLC-MSMS analysis. The columns were used according to manufacturer's instructions; specifically solvents used included a binding solution of 0.1% formic acid in MilliQ water and a releasing solution of 0.1% formic acid in 60% acetonitrile. A 100 μL aliquot of sample was then added to the column with flow through sample recaptured. The column was then washed three times with 50 μL aliquot of binding solution then peptides for analysis were released with two 50 μL aliquots of releasing solution. The solvent was then evaporated and peptides resuspended in 20 μL 2% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid and sonicated prior to mass spectrometry analysis.

The second method involved labeling samples with dimethylation for quantitative analysis. Bacterial samples were brought to room temperature and added to 400 μl of a lysis buffer consisting of 1% Sodium Deoxycholate (SDC; Sigma) 10 mM Tris (2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP; Sigma), 40 mM 2Chloroacetomide (CAA; Sigma Aldrich) in 100 mM HEPES at pH 8.1. Cells were vortexed in lysis buffer then were heated to 95°C for 5 min.

Cells were disrupted with 10 um amplitude probe sonication for three rounds of 30 s, with cooling between cycles. Samples were diluted with 500 μL milliQ water to a final volume of 1 ml. Protein concentration was then determined with BCA kit (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Scientific). Trypsin (Promega) was added to a final enzyme-to-protein ratio of 1:100 and the samples were digested overnight at 37°C.

Samples were then labeled by dimethylation with the reference strain C231 labeled with light (12CH2) formaldehyde and the field isolates labeled with heavy (13CD2) formaldehyde (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). Prior to labeling the pH of each sample was adjusted to seven using formic acid, then either 2 M of light or heavy formaldehyde was added to the respective samples to reach final concentration of 40 mM followed by addition of 1 M NaBH3CN to final concentration of 20 mM. Samples were vortexed and left shaking at room temperature overnight to complete the labeling process. The reaction was quenched with the addition of 1 M glycine to each tube (final 100 mM). An aliquot of each sample (500 μL) was diluted further with 1.5 ml milliQ water, each field isolate was mixed with the same volume of reference strain, following which samples were acidified with formic acid to pH ~2.8. SDC was removed using phase transfer (Masuda et al., 2008). The resulting peptide mixture was fractionated using strong cation exchange cartridge (Bond Elut Plexa PCX, Aglient) with serial elutions of solutions of increasing concentrations of ammonium acetate. The strong cation exchange cartridge was activated with 1 ml of methanol then washed with 1 mL of washing buffer containing 50% (w/v) ethyl acetate, 0.5% (v/v) formic acid, and 50% milliQ water. Samples containing peptides were then loaded onto the cartridge and washed with the same washing buffer three times. Cartridges were then washed with a solution of 0.1% (v/v) formic acid three times. Then samples were eluted sequentially with solutions containing 20% acetronitrile (v/v) and 0.5% formic acid and a variable amount of ammonium acetate (100, 150, 200, 250, 300 mM). The final elution was performed with 80% (v/v) acetonitrile and 5% (v/v) ammonium hydroxide. The solvent was then evaporated with a centrifugal evaporator and then peptides were resuspended in 20 μL 2% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid and sonicated in a water bath sonicator for 10–15 min prior to mass spectrometry analysis.

Mass spectrometry

Samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS using a Q Exactive™ Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) coupled online with a RSLC nano-HPLC (Ultimate 3000, Thermo Scientific) to derive mass spectra of individual peptides and peptide fragment ions were identified with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). Samples were injected onto a Thermo RSLC pepmap100, 75 um id, 100 Å pore size, 50 cm reversed phase nano column with 95% buffer A (0.1% formic acid) at a flow rate of 300 nL/min. The peptides were eluted over a 60-min gradient to 40% buffer B (80% Acetonitrile 0.1% formic acid). The eluate was nebulised and ionized using the Thermo nano electrospray source coated silica emitter with a capillary voltage of 1700 V. Peptides were selected for MS/MS analysis using Xcalibur software (Thermo Finnigan) in Full MS/dd-MS2 (TopN) mode with the following parameter settings: TopN 10, MSMS AGC target 5e4, 120 ms Max IT, NCE 27 and 2 m/z isolation window. Dynamic exclusion was set to 30 s. Generally a single injection was performed for each experimental preparation replicate and two blank injections between each experimental sample.

Analysis of mass spectral data

The quantitative studies described below were included comparison of three biological repeats of the reference strain Cptb_C231 to each of the field isolates. MS label-free and dimethylation data were analyzed with the MaxQuant software (Cox and Mann, 2008) Version 1.5.2.8. Search parameters included specific digestion with Trypsin with up to two missed cleavages: Protein N terminal acetylation (protein) and methionine oxidation were set as variable modifications while cysteine alkylation was set as fixed modfication. The searches were performed against a combined database (Supplementary File, CombinedProteomeDatabase_CptbMerge) generated from all sequenced and annotated genomes of C. pseudotuberculosis Cptb_C231 and the field isolates C. pseudotuberculosis Cptb_RLC001, RLC002 and RLC003, and Cptb C231 sequences downloaded from UniProt (March 2015 version). For label-free analysis the MaxQuant search include the “LFQ” option. Search and quantification using dimethylation were using two labels option using light and heavy dimethylation modification on peptide N-termini and lysine residues. Statistics and further analysis were performed with Perseus framework (version 1.5.1.6). Significant label-free changes were determined using two-sample T-test, while dimethylation significant changes were determined using “Significant A” test (Cox and Mann, 2008).

Likely protein functions were assigned by the COG database (Tatusov et al., 2001), proteins sequence data was searched against the COG target HMM database/bio/db/hmmer3/COG.hmm a database of hidden Markov Models using the hmmpfam program from the HMMER software suite (http://selab.janelia.org/software.html) with predicted orthologous functional group from COG and NCBI. The Inparanoid program (Remm et al., 2001; O'Brien et al., 2005), which is based on reciprocal BLAST, was used for prediction of homology with M. tuberculosis.

Results

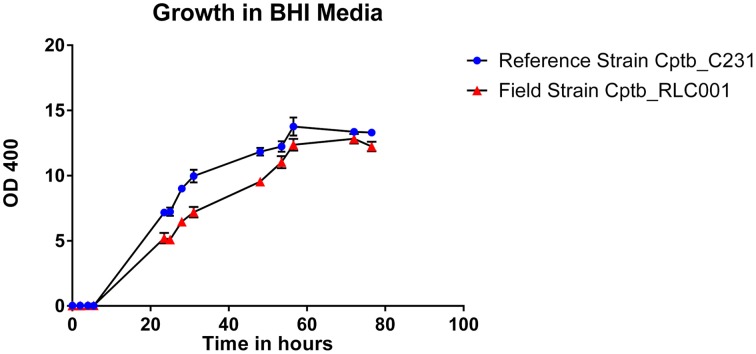

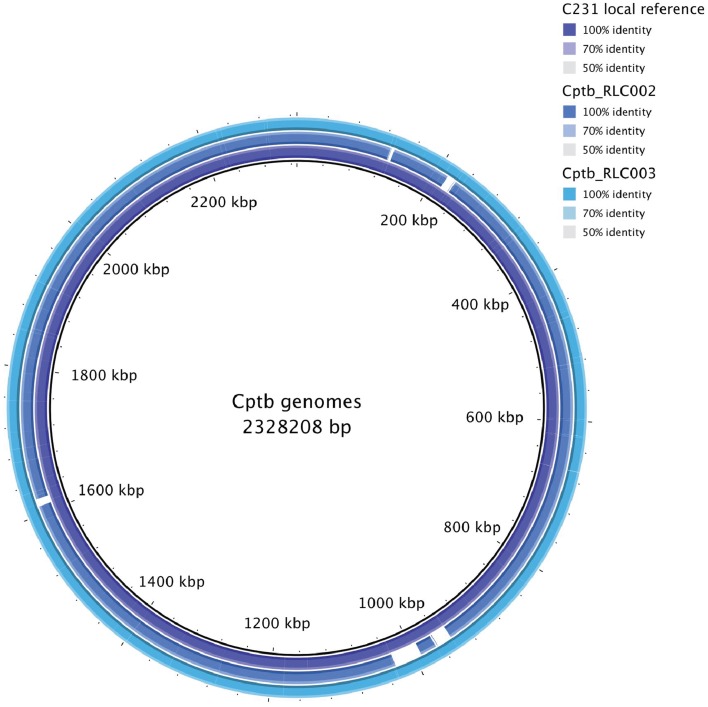

The growth of bacteria in liquid BHI media as measured by optical density was slightly reduced in the field isolate Cptb_RLC001 compared to the reference strain Cptb_C231; this is shown in Figure 1. A summary of genome sequencing results for each strain is listed in Table 1. The whole genome of this isolate was determined (Rees et al., 2015), and comparison of Cptb_RLC001 to the reference genome of C. pseudotuberculosis Cptb_C231 identified a total of 62 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), of which 44 were in coding regions of 38 proteins. Complete genome sequencing of the reference strain Cptb_C231 and the field isolates Cptb_RLC002 and Cptb_RLC_003 demonstrated a high level of similarity between each of the isolates with very few coding sequences absent from the field isolates. This is shown in Figure 2. The vast majority of genes sequenced were found in all four isolates with 1878 genes encoding predicted proteins present in all four isolates (88% of all genes identified), 227 genes present in three of the four isolates and a further 19 genes present in only two isolates.

Figure 1.

Graph demonstrating growth rates in BHI liquid media of a reference strain of C. pseudotuberculosis Cptb_C231 (blue circles) compared to that of the field isolate C. pseudotuberculosis Cptb_RLC001 (red triangles). The chart plots relative cell density in liquid media, as measured by optical density (OD 400), against time in hours. Mean values plotted with error bars representing standard error of the mean. This is a representative growth curve with identical features seen in other field strains.

Figure 2.

Map of whole genome sequencing results demonstrating similarity or identity between the reference strain Cptb_C231 and the field isolates Cptb_RLC002 and Cptb_RLC003.

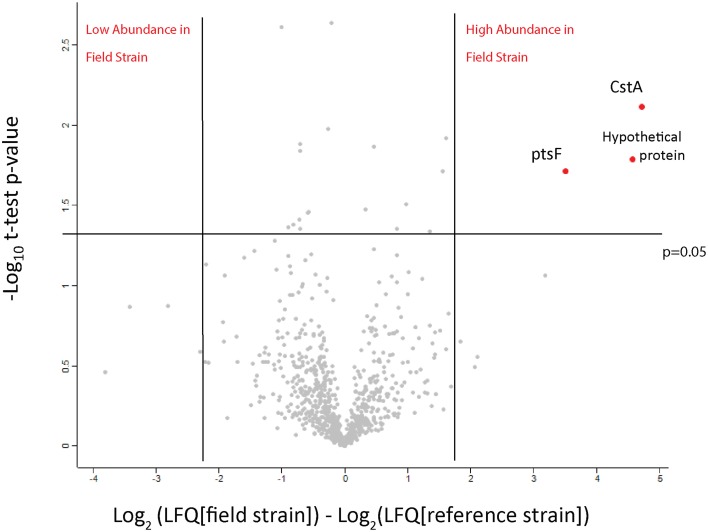

The paucity of substantial genomic variation and the different growth rates of the field strains prompted a comparison of these isolates' proteomes. Initially, we tested the possibility of using quantitative proteomics to detect differences in protein abundance between the isolates. We performed a small scale comparison based on label-free quantification in order to compare the two out of the three field isolates to Cptb_C231 after growth in BHI media. All together over 1250 protein groups were identified and for about 830 of them we were able to obtain a quantitative comparison (Figure 3, and details in Supplementary Table 1, ReesLFQalldb.xlsx) by utilizing label-free quantification based on comparison of peptide numbers and intensity (Cox et al., 2014). Three proteins were found to be significantly more abundant in the field isolates in comparison to the Cptb_C231 (Figure 3, marked in red). These proteins included carbon starvation protein A (pcsA), and PTS system fructose-specific EIIABC component (pstF) and a 42 amino acid long uncharacterized protein GI:503006038 (marked as Cptb_C231_00414, Cptb_RLC_001 _02057, Cptb_RLC_002_01413, and Cptb_RLC_003_00551 in the sequencing data–Supplementary Table 3, CombinedProteomeDatabase_CptbMerge). Blast search of this sequence against NCBI NR database reveal that the latter protein is unique to several strains of C. pseudotuberculosis and C. ulcerans (data not shown). As indicated by the MS/MS search results GI:503006038 is not listed in UniProt database for Cptb_C231 but this gene appeared in all the four sequences we obtained.

Figure 3.

Volcano plot of the observed protein abundance changes by label-free quantification. The protein expression ratio of protein in the field isolates to the reference strains in label-free quantification were plotted against the −log10 of the probability calculated by t-test. Outliers of p = 0.05 and expression fold different (in log2 scale) marked by blue lines.

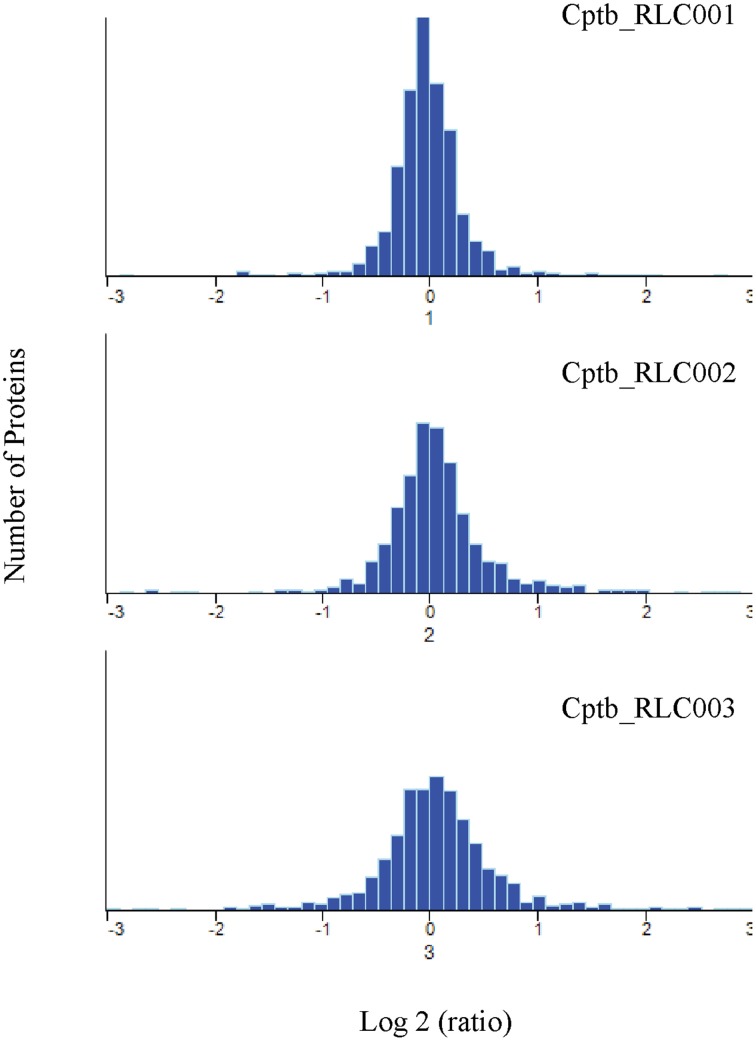

Encouraged by these results we set out to perform a more comprehensive comparison of Cptb_C231 and the field isolate. We utilized dimethylation labeling which allows for simultaneous MS analysis and direct and accurate quantification of the compared proteomes. A total of 1358 C. pseudotuberculosis proteins were identified in these samples, of which it was possible to reliably determine the ratio between Cptb_C231 and at least one field isolate for 1354 proteins (Supplementary Table 2, ReesDiMet.xlsx). This represents good proteome coverage, with 65% of the 2091 proteins predicted from the encoding genome detected. Transcriptional profiling of M. tuberculosis during chronic infection in a mouse model found that 50% of the genome was actively transcribed (Talaat et al., 2007). Therefore, the proteome profiling and quantitative information obtained here most probably capture most of the proteins expressed by the organism at a specific point in time.

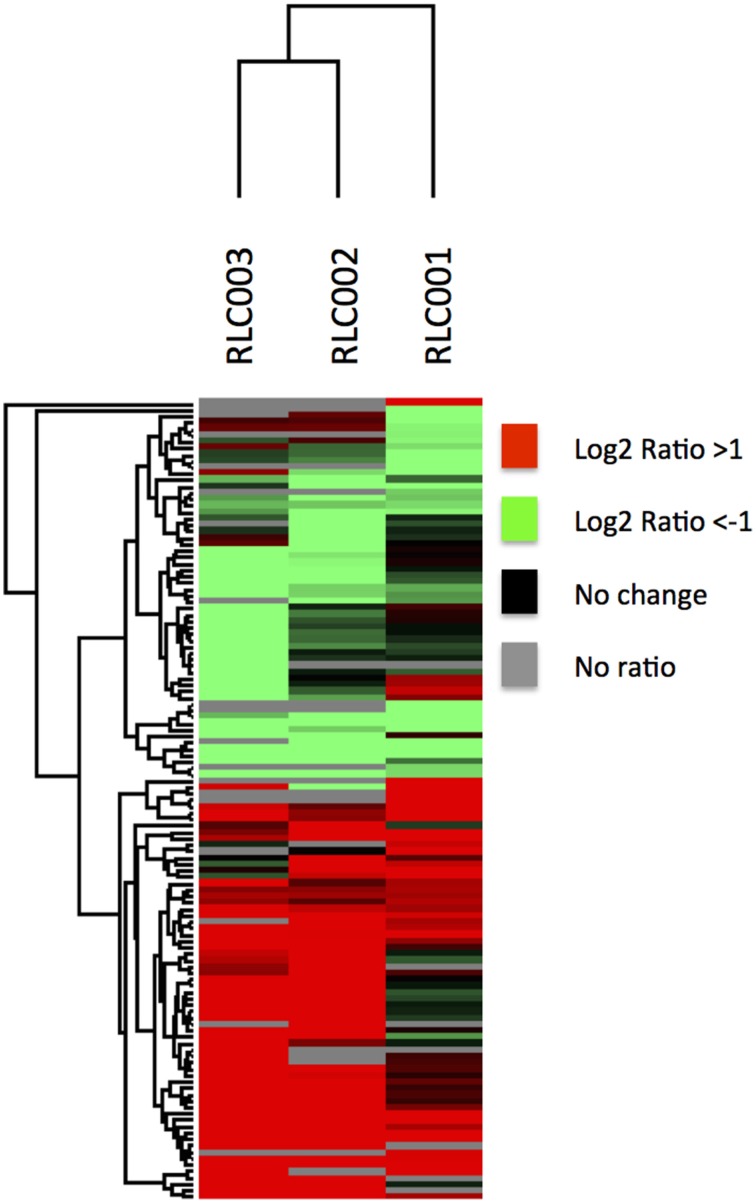

When comparing the relative expression levels of proteins in the field isolates to the reference strain, the vast majority of proteins were at similar abundance spanning from log 2 of −0.5 to 0.5 (Figure 3). The overall distributions of the protein ratios for the three different strains are similar but not identical, which might reflect that these isolates originate from infections of different animals. A similar distribution of protein abundance was seen between each of the three field strains compared to the laboratory reference strain as shown in Figure 4. Small but distinct number of proteins showed significant expression differences between the isolates and the reference strains were selected following statistical analysis. Hierarchical clustering of these proteins (Figure 5) indicates that they can be placed into several groups. Some of these groups show consistent expression profiles across the three different field isolates as indicated by similar color in all three columns. Interestingly, the field isolates were randomly selected from separate animals, and would not be expected to be identical strains, although all share recent exposure to the host environment. We posit that in fact the similar profiles detected here are a result of the demands of the host environment, inducing change in the expression of proteins that assist survival in the host.

Figure 4.

Quantitative comparison by dimethylation. Frequency distribution of Log2 heavy/light ratio for the identified protein groups, indicating similar but not identical protein expression levels for field isolates and reference strain.

Figure 5.

Quantitative comparison by dimethylation. Hierarchical clustering of proteins with significantly altered expression in field isolates relative to the reference strain. The map is color coded to show proteins of increased abundance in the field strain in red, decreased abundance in green, not changed in black and not identified in gray. Some proteins shared very similar expression profiles across all field isolates despite their different origins.

Sixty six proteins demonstrated a significant increase in expression in the field isolates compared to the reference strain (Table 2). Eight of these proteins were significantly increased in all three field isolates. None of the proteins with increased expression was a product of a gene unique to the field isolates. Yet, this approach allowed us to detect differences in protein expression between isolates that were not readily apparent at the genome level. Furthermore, we were able to find evidence for the presence of several protein isoforms reflecting specific SNPs that were identified by genome sequencing. For example, SNP in galactokinase gene in field isolate Cptb_RLC001_001 at position 219 generated a substitution of the original proline to a valine residue (Protein ID: Cptb_RLC_001_00052). The unique peptide containing the valine was identified by MS/MS only in this strain (Supplementary Figure 1, Fragmentation Spectra) while the original proline containing peptide of galactokinase was identified in all other strains (Cptb_C231_01684; Cptb_RLC_003_00699; Cptb_RLC_002_00731; and Uniprot: tr|D9Q9R6|D9Q9R6_CORP2 shown in Supplementary Figure 1, Fragmentation Spectra). The presence of the valine 219 in Cptb_RLC_001_00052 is also reflected in the quantitative analysis that shows that this protein is present only in isolate Cptb_RLC001 and that it is highly overexpressed relative to the reference strain. Closer examination of the results (Supplementary Table 2, ReesDiMetalldb.xlsx–row 1096) show that this is the only unique peptide identified for this protein and the remainder of the peptide repertoire for this protein are shared with the other sequences of galactokinase (Cptb_C231_01684; Cptb_RLC_003_00699; Cptb_RLC_002_00731; and Uniprot: D9Q9R6) and expressed in all strains at similar level (Supplementary Table 2, ReesDiMetalldb.xlsx–row 1204).

Table 2.

Proteins identified with increased abundance in the recently isolated field strains in contrast to the laboratory reference strain.

| Protein ID | Gene | Locus | Protein description | log2 values of increased abundance compared to Cptb_C231 (significant = *) | Predicted function by COG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cptb_RLC001 | Cptb_RLC002 | Cptb_RLC003 | |||||

| D9QD79 | CpC231_0024 | CpC231_0024 | Insertion element protein | 0.314 | 1.687* | Replication and repair | |

| D9QDJ7 | piuB | CpC231_0072 | Uncharacterized iron-regulated membrane protein | 1.509* | 2.303* | Function unknown | |

| D9QDK7 | ulaA | CpC231_0082 | Ascorbate-specific permease IIC component ulaA | −0.319 | 1.199* | 0.835 | Function unknown |

| D9QDP1 | troA | CpC231_0116 | Periplasmic zinc-binding protein troA | 0.799* | 0.648 | 0.614 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| D9QDT5 | deoD | CpC231_0163 | Purine-nucleoside phosphorylase | 1.892* | −0.914 | 0.979 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| D9QDT7 | deoC | CpC231_0165 | Deoxyribose-phosphate aldolase | 1.487* | 0.673 | 2.148* | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| D9QDT8 | pmmB | CpC231_0166 | Phosphoglucosamine mutase | 1.560* | 0.646 | 2.103* | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| D9QE16 | sdhC | CpC231_0245 | Succinate dehydrogenase cytochrome b556 subunit | 2.059* | 2.821* | ||

| D9QE18 | sdhB | CpC231_0247 | Succinate dehydrogenase iron-sulfur subunit | 0.017 | 1.705* | 1.702* | Energy production and conversion |

| D9QE59 | ccdA | CpC231_0288 | Cytochrome c-type biogenesis protein CcdA | 2.695* | Posttranslational modification | ||

| D9QE65 | ccsA | CpC231_0294 | Cytochrome c biogenesis protein CcsA | 0.998* | Posttranslational modification | ||

| D9QE78 | ldh | CpC231_0307 | L-lactate dehydrogenase | −0.209 | 1.437* | 1.364 | Energy production and conversion |

| D9QE89 | CpC231_0319 | CpC231_0319 | Uncharacterized protein | 0.340 | 1.299* | 0.653 | |

| D9QE90 | CpC231_0320 | CpC231_0320 | ABC-type metal ion transport system | −0.250 | 1.354* | 1.615* | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| D9QE94 | CpC231_0324 | CpC231_0324 | Uncharacterized protein | 0.406 | 1.297* | −0.001 | |

| D9QEB4 | CpC231_0345 | CpC231_0345 | Uncharacterized protein | −0.209 | 2.552* | 0.381 | Function unknown |

| D9QED0 | oppDF1 | CpC231_0361 | Oligopeptide transport ATP-binding protein | −0.309 | 1.187* | 1.416* | Posttranslational modification |

| D9QEP1 | pyc | CpC231_0477 | Pyruvate carboxylase | 1.120* | 1.723* | 1.611* | Energy production and conversion |

| D9QEQ2 | rbsR | CpC231_0488 | Ribose operon repressor | 0.751* | 0.892 | 1.014 | Transcription |

| D9QER5 | malE | CpC231_0501 | Maltose/maltodextrin transport system substrate-binding protein | 0.901* | 1.401* | −0.334 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| D9QEV8 | uvrD | CpC231_0544 | DNA helicase | 1.812* | 0.666 | Replication and repair | |

| D9Q9A8 | amtR | CpC231_0651 | TetR family regulatory protein | 0.767* | 0.387 | 1.415* | Transcription |

| D9Q9C3 | CpC231_0666 | CpC231_0666 | 5-formyltetrahydrofolate cyclo-ligase | 1.354* | 1.300* | 1.530* | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| D9Q9D7 | rpfB | CpC231_0680 | Resuscitation-promoting factor RpfB | 0.753* | −0.096 | −1.007 | Function unknown |

| D9Q9E8 | gapA | CpC231_0692 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.843* | 0.394 | 0.669 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| D9Q9J4 | glpX | CpC231_0738 | Fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase | 1.308* | 1.740* | 1.815* | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| D9Q9R3 | CpC231_0807 | CpC231_0807 | Sodium/solute symporter | 2.099* | Posttranslational modification | ||

| D9Q9T2 | CpC231_0827 | CpC231_0827 | Uncharacterized protein | 0.334 | 1.982* | 2.146* | Function unknown |

| D9Q9T3 | lutB | CpC231_0828 | Lactate utilization protein B | 0.234 | 1.888* | 2.065* | Energy production and conversion |

| D9Q9T4 | lutA | CpC231_0829 | Lactate utilization protein A | 0.239 | 1.848* | 2.476* | Energy production and conversion |

| D9Q9Y9 | CpC231_0884 | CpC231_0884 | Uncharacterized protein | 1.794* | |||

| D9QAC0 | cobG | CpC231_1019 | Precorrin-3B synthase | 0.773* | 1.959* | 1.946* | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| D9QAC1 | cobH | CpC231_1020 | Precorrin-8X methyl mutase | −0.111 | 1.440* | 1.324 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| D9QAC2 | cobJ | CpC231_1021 | Precorrin-3B C(17)-methyltransferase | −0.071 | 1.677* | 1.679* | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| D9QAD2 | pafB | CpC231_1031 | Protein pafB | 0.927* | −0.125 | Transcription | |

| D9QAE2 | aspA | CpC231_1041 | Aspartate ammonia-lyase | 0.835* | 1.018 | 1.664* | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| D9QAG6 | CpC231_1066 | CpC231_1066 | SPFH domain, band seven integral membrane protein | −0.075 | 1.213* | 1.581* | Posttranslational modification |

| D9QAH4 | acnA | CpC231_1074 | Aconitate hydratase | 0.665 | 1.274* | 1.321 | Energy production and conversion |

| D9QAQ7 | CpC231_1157 | CpC231_1157 | Citrate lyase subunit beta-like protein | 1.008* | 1.593* | 1.843* | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| D9QAQ8 | CpC231_1158 | CpC231_1158 | MaoC-like dehydratase | 0.746* | 0.737 | 0.789 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| D9QAU4 | rnd | CpC231_1194 | Ribonuclease D | 1.427* | Translation ribosomal structure and biogenesis | ||

| D9QAX8 | ptsF | CpC231_1229 | PTS system fructose-specific EIIABC component | −0.108 | 2.542* | 2.665* | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| D9QBD3 | ftsQ | CpC231_1388 | Cell division protein FtsQ | 1.030* | 0.029 | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis | |

| D9QBF3 | CpC231_1408 | CpC231_1408 | Transcription regulator | 0.978* | 1.194* | 1.055 | |

| D9QBI3 | lipB | CpC231_1439 | Octanoyltransferase | 1.413* | 2.008* | 0.564 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| D9QBL7 | CpC231_1476 | CpC231_1476 | Uncharacterized protein | 0.777* | 1.050 | ||

| D9QBM2 | glnA2 | CpC231_1482 | Glutamine synthetase II | −0.085 | 1.308* | 0.912 | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| D9QBQ8 | CpC231_1518 | CpC231_1518 | HTH-type transcriptional regulator | 0.451 | 1.193* | 2.490* | Transcription |

| D9QC05 | ycaO | CpC231_1619 | Uncharacterized protein ycaO | 1.034* | 1.378* | 2.095* | Function unknown |

| D9QC06 | CpC231_1620 | CpC231_1620 | Nitroreductase | 2.692* | 2.402* | Energy production and conversion | |

| D9QC07 | CpC231_1621 | CpC231_1621 | Lantibiotic dehydratase | 0.549 | 1.898* | 2.185* | |

| D9QC08 | CpC231_1622 | CpC231_1622 | Uncharacterized protein | 0.295 | 1.403* | 1.160 | |

| D9QC16 | pcsA | CpC231_1630 | Carbon starvation protein A | 2.049* | 0.451 | 0.952 | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| D9QC24 | ykuD | CpC231_1638 | L,D-transpeptidase YkuD | 1.515* | Function unknown | ||

| D9QC80 | cydA | CpC231_1695 | Cytochrome d ubiquinol oxidase subunit 1 | 0.268 | 1.523* | Energy production and conversion | |

| D9QCD7 | CpC231_1756 | CpC231_1756 | Uncharacterized protein | 1.445* | 0.921 | −0.298 | |

| D9QCK3 | pknG | CpC231_1823 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase PknG | −0.091 | 0.562 | 1.541* | Signal transduction mechanisms |

| D9QCL1 | dsbB | CpC231_1831 | Disulfide bond formation protein, DsbB family | 1.614* | 1.971* | Posttranslational modification | |

| D9QCN8 | glpD | CpC231_1859 | Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.097 | 1.358* | 1.393* | Energy production and conversion |

| D9QCR2 | CpC231_1885 | CpC231_1885 | Membrane protein | 1.172* | 1.026 | 0.107 | |

| D9QCY5 | glpT1 | CpC231_1960 | Glycerol-3-phosphate transporter | 0.360 | 1.026 | 1.592* | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| D9QCY9 | yvrC | CpC231_1964 | ABC transporter substrate-binding lipoprotein yvrC | 0.775* | 2.659* | 2.942* | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| D9QD08 | deoA | CpC231_1984 | Thymidine phosphorylase | −0.547 | 1.714* | 1.673* | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| D9QD98 | CpC231_2034 | CpC231_2034 | UPF0176 protein | 1.064* | 1.016 | 1.411* | Posttranslational modification |

| D9QDB6 | CpC231_2052 | CpC231_2052 | Uncharacterized protein | 1.998* | 1.661* | 0.803 | |

| Cptb_C231_00414 | GI503006038 | Hypothetical protein | 1.126* | 2.302* | 1.222* | ||

All three proteins that were found to be more abundant in the label-free experiment (Figure 3) were also found to be highly expressed in the field isolates when using dimethylation labeling. The hypothetical protein GI: 503006038 showed higher abundance in all three isolates and pstF was highly expressed only in Cptb_RLC_002 and Cptb_RLC_003, pcsA was shown to have increased abundance (~two fold) in Cptb_RLC_001 and Cptb_RLC_003.

Several groups of proteins which have coding genes located adjacent to each other in the bacterial chromosome appeared to be more abundant in the field isolates (Table 2). Many of these were associated with metabolism. This includes three lactate utilization proteins encoded by genes CpC231_0827 to CpC231_0829, which demonstrated increased abundance in all three field isolates in contrast to the reference strain. CpC231_0829 is lactate utilization protein A (LutA), CpC231_0828 is lactate utilization protein B (LutB) while CpC231_0827 is an uncharacterized protein. BLAST and homolog search for CpC231_0827 show that this protein includes a 5-formyltetrahydrofolate cyclo-ligase domain found in enzymes involved in folate metabolism and also Lactate utilization protein C (LutC) and LutB. This indicated that this operon is probably the lutABC identified in other species (Hwang et al., 2013). This operon has been observed to be activated, and the expression of these proteins elevated, in response to altered nutrient availability in the host (Gerstmeir et al., 2003). The availability of altered carbon sources in host tissue may similarly explain the increased abundance of carbon starvation protein (pcsA).

Another cluster of proteins with increased expression in the field isolate is encoded in the gene region from CpC231_1019 to CpC231_1021. All of these have been predicted to reside in a shared operon (http://www.coryneregnet.de) and are involved with Precorrin. These genes have homologs in the cob gene products of M. tuberculosis (genes Rv2064 to Rv2066) and contribute to biochemical pathways involved in cobalamin and vitamin B12 synthesis (Raux et al., 2000). The PTS system fructose-specific EIIABC component (pstF) was found to be increased in abundance by both quantitative proteomic methods in our study. This system has been described to be carbohydrate regulated in the closely related C. glutamicum, in which it both responds to alternate carbon sources and facilitates up take of alternate carbohydrates (Ikeda, 2012).

Another group of proteins that share the same operon control and show increased abundance in the field isolates are those coded by the genes CpC231_1619 to 1622. These proteins are annotated as ycaO, the ribosomal protein S12 methylthiotransferase accessory factor (CpC231_1619), Nitroreductase (CpC231_1620) member of the Lantibiotic dehydratase family (CpC231_1621) and uncharacterized protein (CpC231_1622). BLAST and homolog searches reveal that the later contains a thiopeptide-type bacteriocin biosynthesis domain, consistent with a lantibiotic dehydratase domain. These four proteins and domains are involved in thiopeptide biosynthesis (Li et al., 2012) Indicating that this operon and the synthesis of thiopeptide are activated in the field isolate at much higher level than in the reference strain.

Fifty-six proteins were less abundant in the field isolates (Table 3) in comparison to the reference strain of which four were decreased in all three field isolates. Many of these proteins are involved in metabolic processes including two glutamate binding proteins (GluA and B), and an iron binding protein (fhuD) and a phosphate binding protein (pstS), suggesting that the field isolates have been primed to select for different nutrients. Similar to the clusters of proteins with elevated abundance, there were also proteins which are encoded by the same operon which were decreased in abundance. This includes the operon between CpC231_1833 and CpC231_1835, although the specific function of these proteins is unknown all three of them were reported to be exported proteins (Silva et al., 2013).

Table 3.

Proteins identified with significantly decreased abundance in the recently isolated field strains in contrast to the laboratory reference strain.

| Protein ID | Gene | Locus | Protein description | log2 values of decreased abundance | Predicted function by COG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compared to Cptb_C231 (significant = *) | |||||||

| Cptb_RLC001 | Cptb_RLC002 | Cptb_RLC003 | |||||

| Cptb_C231_00778 | Cp31_0599 | Cp31_0599 | hypothetical protein | −1.205* | −2.560* | ||

| D9QDJ0 | CpC231_0064 | CpC231_0064 | Lysozyme M1 | −0.099 | −0.173 | −1.368* | Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis |

| D9QDQ0 | CpC231_0126 | CpC231_0126 | Glyoxalase/Dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase | −0.281 | −0.943* | −1.297* | General function prediction only |

| D9QDQ6 | pdxT | CpC231_0132 | Pyridoxal 5′-phosphate synthase subunit PdxT | −1.452* | −0.796 | 0.654 | Coenzyme transport and metabolism |

| D9QDR1 | mmpL11 | CpC231_0137 | Uncharacterized protein | −2.842* | General function prediction only | ||

| D9QDU5 | CpC231_0173 | CpC231_0173 | Surface antigen | −1.217* | |||

| D9QDW8 | CpC231_0196 | CpC231_0196 | Uncharacterized protein | −0.537 | −0.765 | −1.913* | |

| D9QDZ8 | cspA | CpC231_0227 | Cold-shock protein | −0.223 | −0.090 | −1.352* | Transcription |

| D9QE05 | CpC231_0234 | CpC231_0234 | Secreted hydrolase | 0.139 | −0.448 | −1.603* | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| D9QE11 | slpA | CpC231_0240 | Surface layer protein A | −0.052 | −0.399 | −1.462* | General function prediction only |

| D9QE86 | nemA | CpC231_0316 | N-ethylmaleimide reductase | −0.269 | −0.514 | −1.300* | Energy production and conversion |

| D9QEF8 | CpC231_0391 | CpC231_0391 | L,D-transpeptidase catalytic domain, region YkuD | 0.604 | −0.590 | −1.639* | Function unknown |

| D9QEL9 | htaA | CpC231_0454 | Cell−surface hemin receptor | −0.567 | −0.942* | ||

| D9QEM3 | htaC | CpC231_0458 | Uncharacterized protein | 0.030 | −0.838 | −1.610* | |

| D9QEQ0 | maf | CpC231_0486 | Maf-like protein CpC231_0486 | −0.886* | 0.324 | −0.300 | Cell cycle control |

| D9QEQ5 | pccB2 | CpC231_0491 | Propionyl-CoA carboxylase beta chain 2 | 0.201 | −2.348* | −2.676* | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| D9QEV7 | CpC231_0543 | CpC231_0543 | Uncharacterized protein | −0.923* | −1.119* | −0.183 | |

| D9Q935 | CpC231_0574 | CpC231_0574 | Methylmalonyl-CoA carboxyltransferase 1.3S subunit | −1.088* | −0.381 | −0.228 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| D9Q954 | rpfA | CpC231_0595 | Resuscitation-promoting factor | 0.724 | −0.020 | −1.458* | |

| D9Q998 | pcrA | CpC231_0641 | DNA helicase | 0.070 | −1.359* | −1.895* | Replication recombination and repair |

| D9Q9A3 | gluA | CpC231_0646 | Glutamate ABC transporter domain-containing ATP-binding protein | −1.015* | −2.494* | −1.443* | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| D9Q9A4 | gluB | CpC231_0647 | Glutamate-binding protein GluB | −0.990* | −2.238* | −1.513* | Amino acid transport and metabolism |

| D9Q9H2 | gppA2 | CpC231_0716 | Ppx/GppA phosphatase family | −1.726* | −2.633* | −0.665 | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| D9Q9L9 | sprX | CpC231_0763 | Trypsin-like serine protease | 0.088 | −0.902 | −2.282* | Posttranslational modification |

| D9Q9R9 | CpC231_0813 | CpC231_0813 | Glyoxalase/Dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase | −0.710 | −1.072* | −0.552 | Function unknown |

| D9Q9T0 | CpC231_0824 | CpC231_0824 | Uncharacterized protein | −0.893* | −1.360* | −0.543 | |

| D9Q9Y3 | fhuD | CpC231_0878 | Iron(3+)-hydroxamate-binding protein fhuD | −1.756* | −1.569* | −1.711* | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| D9QA16 | gpsA | CpC231_0913 | Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.005 | −1.388* | 0.405 | Energy production and conversion |

| D9QA35 | ptsG | CpC231_0932 | Phosphotransferase system II Component | −0.800* | −0.370 | 0.481 | Carbohydrate transport and metabolism |

| D9QAE1 | fhs | CpC231_1040 | Formate–tetrahydrofolate ligase | −1.007* | 0.355 | 0.293 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| D9QAL4 | ribD | CpC231_1114 | Riboflavin biosynthesis protein ribD | −1.737* | Coenzyme transport and metabolism | ||

| D9QAL9 | priA | CpC231_1119 | Primosomal protein N | −0.786* | Replication recombination and repair | ||

| D9QAN5 | efp | CpC231_1135 | Elongation factor P | −0.110 | −1.051* | −0.304 | Translation ribosomal structure and biogenesis |

| D9QB52 | pyrH | CpC231_1306 | Uridylate kinase | −0.879* | 0.476 | 0.459 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| D9QBH1 | CpC231_1426 | CpC231_1426 | Iron-sulfur cluster insertion protein erpA | −0.371 | −2.254* | −0.648 | Function unknown |

| D9QBL4 | CpC231_1473 | CpC231_1473 | Uncharacterized protein | −0.052 | −0.227 | −1.565* | Function unknown |

| D9QBM5 | CpC231_1485 | CpC231_1485 | Uncharacterized protein | 0.115 | −0.299 | −1.459* | |

| D9QBU6 | CpC231_1558 | CpC231_1558 | Uncharacterized protein | −0.325 | −1.561* | −1.290* | General function prediction only |

| D9QBZ1 | CpC231_1605 | CpC231_1605 | Uncharacterized protein | 0.294 | −0.116 | −1.637* | |

| D9QC41 | CpC231_1655 | CpC231_1655 | Uncharacterized protein | −0.163 | −1.052* | 0.280 | |

| D9QC90 | pstS | CpC231_1706 | Phosphate-binding protein PstS | −0.789* | −2.400* | −2.551* | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| D9QCE7 | iunH2 | CpC231_1766 | Inosine-uridine preferring nucleoside hydrolase | −1.783* | −0.735 | −1.189 | Nucleotide transport and metabolism |

| D9QCH2 | lipY | CpC231_1792 | Secretory lipase | −0.629 | −0.755 | −1.690* | General function prediction only |

| D9QCJ4 | def | CpC231_1814 | Peptide deformylase | −0.287 | −1.257* | Translation ribosomal structure and biogenesis | |

| D9QCL3 | CpC231_1833 | CpC231_1833 | Uncharacterized protein | −0.788* | −0.725 | −0.672 | |

| D9QCL4 | CpC231_1834 | CpC231_1834 | Uncharacterized protein | −1.593* | 0.453 | ||

| D9QCL5 | CpC231_1835 | CpC231_1835 | Uncharacterized protein | −1.309* | −0.473 | −0.251 | |

| D9QCM3 | CpC231_1843 | CpC231_1843 | Uncharacterized protein | −1.305* | |||

| D9QCM5 | CpC231_1845 | CpC231_1845 | Uncharacterized protein | 0.905* | −0.335 | −1.832* | |

| D9QCN2 | CpC231_1852 | CpC231_1852 | Sdr family related adhesin | −1.734* | |||

| D9QCR4 | hspR | CpC231_1887 | Heat shock protein HspR | −0.867* | Transcription | ||

| D9QCX0 | ppsA | CpC231_1945 | Phthiocerol synthesis polyketide synthase type I PpsA | −0.073 | −1.249* | −1.193 | Lipid transport and metabolism |

| D9QCX4 | cmtC | CpC231_1949 | Trehalose corynomycolyl transferase C | −0.139 | −0.382 | −1.470* | General function prediction only |

| D9QCY4 | glpQ | CpC231_1959 | Glycerophosphoryl diester phosphodiesterase | −0.412 | −2.820* | −2.898* | Energy production and conversion |

| D9QD39 | CpC231_2016 | CpC231_2016 | Cation transport protein | −0.331 | −0.089 | −1.344* | Inorganic ion transport and metabolism |

| D9QDE3 | trpC | CpC231_2079 | Bifunctional indole-3-glycerol phosphate synthase | −0.114 | −1.241* | −0.166 | |

C. pseudotuberculosis is an animal pathogen that has not been extensively studied however many of the proteins we identified as differentially abundant in field strains had homologs in M. tuberculosis, a significant human pathogen. These include proteins that are known to be differentially regulated in a hypoxic environment on the basis of transcriptional profiling, such as the increased expression of Nudix hydrolase (nudL; Park et al., 2003), pyruvate carboxylase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (glpX; Rustad et al., 2009) and decreased expression of riboflavin biosynthesis protein RibD (Rustad et al., 2008). There is also a pair of more abundant proteins that are encoded by adjacent genes CpC231_0165 and CpC231_0166 which have homologs deoC and pmmB in M. tuberculosis. The protein product of pmmB has been suggested as contributing to the production of mannose in the mycobacterial cell wall (Mishra et al., 2012), a significant bacterial defense against the host.

A Clusters of Orthologous Groups analysis was performed on these proteins to predict likely function. A functional group could be predicted for 94 of the proteins that had demonstrated significant alterations of abundance in the field isolates. The remaining 30 did not have any predicted function. The majority of these proteins had some sort of metabolic function including utilization of metabolites such as amino acids and lipids (Tables 2, 3). Energy production and conservation was the functional group with the greatest number of proteins allocated, suggesting that the field isolates had needed to alter their metabolism in response to the recent host environment.

Discussion

This aim of this work was to characterize the proteomic differences between C. pseudotuberculosis isolated from naturally infected sheep and a laboratory reference strain. While infection of cultured cell lines is commonly utilized to study bacterial genomic and proteomic changes occurring in the host cell (Shi et al., 2006; Pávková et al., 2013) there are fewer studies of bacteria isolated from infected host (Twine et al., 2006; Schmidt and Volker, 2011; Rees et al., 2015). One of the challenges in such studies is to collect sufficient amount of bacteria to allow thorough proteomics analysis (Schmidt and Volker, 2011).

In this study we used a different approach to address this technical challenge, simply by culturing freshly isolated bacteria in BHI media and compare it to a laboratory reference strain of C. pseudotuberculosis growing under identical conditions. The adaptation of the isolated field strains to their source growth conditions persisted despite brief culturing in liquid media and this allowed us to detect clear and distinguishable changes between the field strains and the laboratory reference strain.

Mass spectrometry based proteomic analyses are currently limited to identification of several thousands of proteins (Richards et al., 2015). This might be a limitation for studies of eukaryotes and mammals but should not affect studies of prokaryotic organisms with relatively small genomes such as C. pseudotuberculosis. Indeed, our results have demonstrated that almost complete proteome coverage can be achieved. We identified and quantified >1350 proteins and >60% of the predicted ORFs which is providing significantly wider coverage of C. pseudotuberculosis genome compared to previous reports (Silva et al., 2014).

In this study the genomic and the proteomic mappings provide similar general conclusions regarding the similarity between the field strains and reference strain. We note that >10% of genes differed between sequences due to the presence of SNPs or the presence or absence of genes. Similarly, about 10% of the protein repertoire differed in abundance between the samples. However, the proteins that differed in abundance were not those predicted to be transcribed by altered genes but were transcribed of genes shared and conserved across all isolates and reference strain. The field isolates were collected from the same geographical area so it is possible that these strains share some genetic changes or epigenetic mechanism that does not present in the reference strain that might lead to the observed proteomic differences. However, the relevant geographic area is rather large (South western Victoria consist of ~60,000 km2) and the field isolates were collected from different animals on different time points, which reduces the feasibility of these options as well as our genetic data indicating very high similarity in between the field isolates and reference strains (Figure 2).

The isolated bacteria were cultured for a relative short time in synthetic media prior to genetic and proteomic analyses. It is possible, that under these less-stressed conditions, not all of the proteomic changes that occur in host will appear. Yet, the “stress-relief”-related changes that can be detected during the adaptation of the field isolates to the synthetic media are useful indicators to the mechanisms the bacteria are using in order to survive and thrive within the host. As the field strains were recently isolated from sheep lymph nodes it can be postulated that proteins involved in resistance to the hostile environment of the caseous lymph node may be primed to have an increase in expression. C. pseudotuberculosis residing in caseous lymph nodes will often be consumed by macrophages, but survive this phagocytosis and reside in the lysozyme compartment which is known to be hypoxic (Pacheco et al., 2012) Protein repertoires have been demonstrated to differ between hypoxic and normally growing M. tuberculosis (Wolfe et al., 2013). Therefore, it is not surprising that proteins that are implicated in dealing with a hypoxic environment such as pyc and glpX (listed in Table 2) are present in increased quantities in strains recently isolated from lymph nodes, compared to strains which have been passaged many times in liquid media that has been aerated by continuous shaking.

Bacterial liquid culture media, such as BHI, have readily available carbon sources such as carbohydrates however bacterial growth within the host lymph node may require the utilization of alternate nutrients. This could be done by several proteins derived by the sdhABC operon encoding succinate dehydrogenase (CpC231_0245 to CpC231_0247). It is of interest that succinate dehydrogenase proteins were found to be elevated in the field isolates, as these enzymes have previously been noted to be a significant aspect of the metabolic pathways evoked when bacteria have to adapt to different environments. Specifically, SDH expression is seen to be increased in response to hypoxic conditions (Inui et al., 2004) and during growth on metabolic substrates other than glucose such as lactate and acetate (Gerstmeir et al., 2003; Bussmann et al., 2009). SDH expression is also part of the enzymatic switch from glucose to acetate (Wolfe, 2005). The mechanism by which this occurs is not fully elucidated but was reported to be controlled by several regulatory systems, including that expression induction by RamA and repression by GlxR (Bussmann et al., 2009). Elevated abundance of proteins such as succinate dehydrogenase suggests that these field isolates have adapted to the environment of the host and more readily produce these proteins than laboratory strains. In our analysis no DNA sequence changes were noted in either GlxR (CptbC231_0208) or CpC231_0244 which is a transcriptional regulator that bears homology to RamB. Interestingly, there was one SNP in the coding region of the serine proteases family genes at CpC231_0239 which is considered a response regulator by bioinformatics prediction (Caspi et al., 2014). Further qPCR studies of the genes encoding the differentially expressed proteins would be needed to determine the mechanism.

An intriguing discovery is the increased expression of proteins from the gene cluster encoding thiopeptide biosynthesis (genes CpC231_1619 to 1622–Table 2). These uniquely modified peptides have antibacterial activity as well as anti-tumor activity and other capabilities. The antibacterial activity of thiopeptides suggests these peptides may be used to obtain advantage over other bacterial species and dominate their ecological niche (Ruhe et al., 2013). The increased abundance of thiopepetide synthesis cluster proteins seen in the field isolates may contribute to their dominance in the host. The extent to which competition between bacterial commensals occurs in lymph nodes is unclear. In contrast to mammalian host surfaces such as gut and upper airways, which normally host diverse populations of bacteria, any bacteria transported to the lymph nodes via the lymphatic circulation are quickly attacked by the abundant resident immune cells particularly phagocytes (von Andrian and Mempel, 2003). However, certain pathogens can replicate at this site in disease. There is evidence at the transcriptional level of microbes in apparently healthy lymph nodes which supports their role as concentrators of the commensal, endemic, and potential pathogenic microbial communities of a host species (Wittekindt et al., 2010). Therefore, the capacity of a microorganism to generate an antimicrobial peptide to exert its dominance over a mixed population of bacteria would certainly be an advantage for bacteria such as C. pseudotuberculosis when establishing infection in the inoculating wound (Dorella et al., 2006) and subsequently in the respiratory tract (Bush et al., 2012) and possibly also in the lymph nodes.

It was recently shown that six genes that are involved in the synthesis and secretion of the thiopeptide bacteriocin could modulate the immune response of dendritic cells toward the probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 (Kindrachuk et al., 2013). Furthermore, a different study revealed that nicin Z, one of the best studied thiopeptide, can induce the secretion of different chemokines and modulate the host immune response to bacterial infection (Meijerink et al., 2010). Therefore, it is possible that the increased expression of thiopeptide synthesis proteins is a mechanism that allows the bacteria to modulate the host innate immune responses. This in turn may provide these field isolates selective advantage within the host particularly within immune-reactive lymph nodes.

Decreased abundance in the field isolates compared to the laboratory reference strain was also documented (Table 3). Proteins that were shown to have significantly lower expression in all filed isolates include the phosphate-binding protein pstS also known as Phosphate ABC transporter. In M. tuberculosis inactivation of similar genes was linked to reduced virulence (Peirs et al., 2005) and pstC was shown to act also as adhesion molecule that can bind macrophages and promote phagocytosis (Sanchez et al., 2009). In Corynebacterium glutamicum this gene transcription is controlled by the RamB via phosphate sensitive regulation that involve GlxR and phoRS (Sorger-Herrmann et al., 2015) Phosphate dependency was also documented in Clostridium acetobutylicum where pstC expression is induced only under conditions of organic phosphate limitation (Fischer et al., 2006). It is likely that the reduced abundance of PstC we observed in the field isolates is the results of the relatively high phosphate concentration in the BHI growth media used in our experiments. Similarly, we observed decreased abundance in the field isolates of several proteins involved in metabolic processes such as glutamate utilization, iron uptake which may reflect altered availability of these substrates in the host compared with the culture media. The riboflavin biosynthesis proteins RibD was also less abundant, and this is in agreement with microarray studies in which the M. tuberculosis homolog ribG has been noted to be down regulated in hypoxia (Rustad et al., 2008).

A successful pathogen will need a dynamic repertoire of expressed proteins to counter the hostile environment of the host. This comprehensive quantitative whole proteome analysis comparing different isolates has identified groups of proteins that are likely to work together in response to the host environment, thus providing different and complementary information to that derived from genome sequencing. Identified proteins with increased abundance were consistent with those that could be anticipated to occur in response to the hostile host environment. These included proteins that respond to the hypoxic environment of the host as well as those involved in metabolism of a different set of carbon sources and thiopeptide biosynthesis. Yet, the differential abundance of some sets of proteins in field isolates from infected hosts is currently unexplained, further investigation of these proteins may provide information to begin to unravel the complex interaction between pathogen and host.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of M.C. Herd, Pty Ltd, Geelong, and Dr Rob Moore from Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australian Animal Health Laboratory, Geelong.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fcimb.2015.00071

ReesLFQ.xlsx.

ReesDiMet.xlsx.

Fasta files whole sequence predicted proteomes of all isolates.

MS/MS spectra of galactokinase SNP.

References

- Baird G. J., Fontaine M. C. (2007). Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis and its role in ovine caseous lymphadenitis. J. Comp. Pathol. 137, 179–210. 10.1016/j.jcpa.2007.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrell D. H. (1978). Experimental induction of caseous lymphadenitis in sheep by intralymphatic inoculation of Corynebacterium ovis. Res. Vet. Sci. 24, 269–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush R. D., Barnett R., Links I. J., Windsor P. A. (2012). Using abattoir surveillance and producer surveys to investigate the prevalence and current preventative management of Caseous lymphadenitis in Merino flocks in Australia. Anim. Prod. Sci. 52, 675–679. 10.1071/AN11271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann M., Emer D., Hasenbein S., Degraf S., Eikmanns B. J., Bott M. (2009). Transcriptional control of the succinate dehydrogenase operon sdhCAB of Corynebacterium glutamicum by the cAMP-dependent regulator GlxR and the LuxR-type regulator RamA. J. Biotechnol. 143, 173–182. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi R., Altman T., Billington R., Dreher K., Foerster H., Fulcher C. A., et al. (2014). The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of Pathway/Genome Databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D459–D471. 10.1093/nar/gkt1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J., Hein M. Y., Luber C. A., Paron I., Nagaraj N., Mann M. (2014). Accurate proteome-wide label-free quantification by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction, termed MaxLFQ. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 13, 2513–2526. 10.1074/mcp.M113.031591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J., Mann M. (2008). MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372. 10.1038/nbt.1511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorella F. A., Pacheco L. G., Oliveira S. C., Miyoshi A., Azevedo V. (2006). Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis: microbiology, biochemical properties, pathogenesis and molecular studies of virulence. Vet. Res. 37, 201–218. 10.1051/vetres:2005056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer R. J., Oehmcke S., Meyer U., Mix M., Schwarz K., Fiedler T., et al. (2006). Transcription of the pst operon of Clostridium acetobutylicum is dependent on phosphate concentration and pH. J. Bacteriol. 188, 5469–5478. 10.1128/JB.00491-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine M. C., Baird G. J. (2008). Caseous lymphadenitis. Small Rumin. Res. 76, 42–48. 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2007.12.025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstmeir R., Wendisch V. F., Schnicke S., Ruan H., Farwick M., Reinscheid D., et al. (2003). Acetate metabolism and its regulation in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biotechnol. 104, 99–122. 10.1016/S0168-1656(03)00167-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güell M., Yus E., Lluch-Senar M., Serrano L. (2011). Bacterial transcriptomics: what is beyond the RNA horiz-ome? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 658–669. 10.1038/nrmicro2620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W. C., Bakolitsa C., Punta M., Coggill P. C., Bateman A., Axelrod H. L., et al. (2013). LUD, a new protein domain associated with lactate utilization. BMC Bioinformatics 14:341. 10.1186/1471-2105-14-341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M. (2012). Sugar transport systems in Corynebacterium glutamicum: features and applications to strain development. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 96, 1191–1200. 10.1007/s00253-012-4488-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui M., Murakami S., Okino S., Kawaguchi H., Vertès A. A., Yukawa H. (2004). Metabolic analysis of Corynebacterium glutamicum during lactate and succinate productions under oxygen deprivation conditions. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 7, 182–196. 10.1159/000079827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindrachuk J., Jenssen H., Elliott M., Nijnik A., Magrangeas-Janot L., Pasupuleti M., et al. (2013). Manipulation of innate immunity by a bacterial secreted peptide: lantibiotic nisin Z is selectively immunomodulatory. Innate Immun. 19, 315–327. 10.1177/1753425912461456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Qu X., He X., Duan L., Wu G., Bi D., et al. (2012). ThioFinder: a web-based tool for the identification of thiopeptide gene clusters in DNA sequences. PLoS ONE 7:e45878. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda T., Tomita M., Ishihama Y. (2008). Phase transfer surfactant-aided trypsin digestion for membrane proteome analysis. J. Proteome Res. 7, 731–740. 10.1021/pr700658q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijerink M., van Hemert S., Taverne N., Wels M., de Vos P., Bron P. A., et al. (2010). Identification of genetic loci in Lactobacillus plantarum that modulate the immune response of dendritic cells using comparative genome hybridization. PLoS ONE 5:e10632. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A. K., Krumbach K., Rittmann D., Batt S. M., Lee O. Y. C., De S., et al. (2012). Deletion of manC in Corynebacterium glutamicum results in a phospho-myo-inositol mannoside- and lipoglycan-deficient mutant. Microbiology 158, 1908–1917. 10.1099/mic.0.057653-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien K. P., Remm M., Sonnhammer E. L. L. (2005). Inparanoid: a comprehensive database of eukaryotic orthologs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, D476–D480. 10.1093/nar/gki107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco L. G. C., Castro T. L. P., Carvalho R. D., Moraes P. M., Dorella F. A., Carvalho N. B., et al. (2012). A role for sigma factor σE in Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis resistance to nitric oxide/peroxide stress. Front. Microbiol. 3:126. 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H.-D., Guinn K. M., Harrell M. I., Liao R., Voskuil M. I., Tompa M., et al. (2003). Rv3133c/dosR is a transcription factor that mediates the hypoxic response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 833–843. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03474.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pávková I., Brychta M., Strašková A., Schmidt M., Macela A., Stulík J. (2013). Comparative proteome profiling of host-pathogen interactions: insights into the adaptation mechanisms of Francisella tularensis in the host cell environment. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 10103–10115. 10.1007/s00253-013-5321-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel M. M., Palmer G. G., Stacpoole A. M., Kerr T. G. (1997). Human lymphadenitis due to Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis: report of ten cases from Australia and review. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24, 185–191. 10.1093/clinids/24.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirs P., Lefèvre P., Boarbi S., Wang X. M., Denis O., Braibant M., et al. (2005). Mycobacterium tuberculosis with disruption in genes encoding the phosphate binding proteins PstS1 and PstS2 is deficient in phosphate uptake and demonstrates reduced in vivo virulence. Infect. Immun. 73, 1898–1902. 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1898-1902.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raux E., Schubert H. L., Warren M. J. (2000). Biosynthesis of cobalamin (vitamin B12): a bacterial conundrum. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57, 1880–1893. 10.1007/PL00000670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees M. A., Kleifeld O., Crellin P. K., Ho B., Stinear T. P., Smith A. I., et al. (2015). Proteomic characterization of a natural host-pathogen interaction: repertoire of in vivo expressed bacterial and host surface-associated proteins. J. Proteome Res. 14, 120–132. 10.1021/pr5010086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remm M., Storm C. E., Sonnhammer E. L. (2001). Automatic clustering of orthologs and in-paralogs from pairwise species comparisons. J. Mol. Biol. 314, 1041–1052. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.5197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards A. L., Merrill A. E., Coon J. J. (2015). Proteome sequencing goes deep. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 24, 11–17. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhe Z. C., Low D. A., Hayes C. S. (2013). Bacterial contact-dependent growth inhibition. Trends Microbiol. 21, 230–237. 10.1016/j.tim.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz J. C., D'Afonseca V., Silva A., Ali A., Pinto A. C., Santos A. R., et al. (2011). Evidence for reductive genome evolution and lateral acquisition of virulence functions in two Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis strains. PLoS ONE 6:e18551. 10.1371/journal.pone.0018551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumble S. M., Lacroute P., Dalca A. V., Fiume M., Sidow A., Brudno M. (2009). SHRiMP: accurate mapping of short color-space reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 5:e1000386. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustad T. R., Harrell M. I., Liao R., Sherman D. R. (2008). The enduring hypoxic response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 3:e1502. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rustad T. R., Sherrid A. M., Minch K. J., Sherman D. R. (2009). Hypoxia: a window into Mycobacterium tuberculosis latency. Cell. Microbiol. 11, 1151–1159. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01325.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez A., Espinosa P., Esparza M. A., Colon M., Bernal G., Mancilla R. (2009). Mycobacterium tuberculosis 38-kDa lipoprotein is apoptogenic for human monocyte-derived macrophages. Scand. J. Immunol. 69, 20–28. 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt F., Völker U. (2011). Proteome analysis of host-pathogen interactions: investigation of pathogen responses to the host cell environment. Proteomics 11, 3203–3211. 10.1002/pmic.201100158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Adkins J. N., Coleman J. R., Schepmoes A. A., Dohnkova A., Mottaz H. M., et al. (2006). Proteomic analysis of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium isolated from RAW 264.7 macrophages: identification of a novel protein that contributes to the replication of serovar Typhimurium inside macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29131–29140. 10.1074/jbc.M604640200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva W. M., Carvalho R. D., Soares S. C., Bastos I. F. S., Folador E. L., Souza G. H. M. F., et al. (2014). Label-free proteomic analysis to confirm the predicted proteome of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis under nitrosative stress mediated by nitric oxide. BMC Genomics 15:1065. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva W. M., Seyffert N., Ciprandi A., Santos A. V., Castro T. L. P., Pacheco L. G. C., et al. (2013). Differential exoproteome analysis of two Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis biovar ovis strains isolated from goat (1002) and sheep (C231). Curr. Microbiol. 67, 460–465 10.1007/s00284-013-0388-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorger-Herrmann U., Taniguchi H., Wendisch V. (2015). Regulation of the pstSCAB operon in Corynebacterium glutamicum by the regulator of acetate metabolism RamB. BMC Microbiol. 15:113. 10.1186/s12866-015-0437-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talaat A. M., Ward S. K., Wu C. W., Rondon E., Tavano C., Bannantine J. P., et al. (2007). Mycobacterial bacilli are metabolically active during chronic tuberculosis in murine lungs: insights from genome-wide transcriptional profiling. J. Bacteriol. 189, 4265–4274. 10.1128/JB.00011-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusov R. L., Natale D. A., Garkavtsev I. V., Tatusova T. A., Shankavaram U. T., Rao B. S., et al. (2001). The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 22–28. 10.1093/nar/29.1.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost E., Ott L., Schneider J., Schröder J., Jaenicke S., Goesmann A., et al. (2010). The complete genome sequence of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis FRC41 isolated from a 12-year-old girl with necrotizing lymphadenitis reveals insights into gene-regulatory networks contributing to virulence. BMC Genomics 11:728. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twine S. M., Mykytczuk N. C., Petit M. D., Shen H., Sjöstedt A., Wayne Conlan J., et al. (2006). In vivo proteomic analysis of the intracellular bacterial pathogen, Francisella tularensis, isolated from mouse spleen. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 345, 1621–1633. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Andrian U. H., Mempel T. R. (2003). Homing and cellular traffic in lymph nodes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 867–878. 10.1038/nri1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weigoldt M., Meens J., Doll K., Fritsch I., Möbius P., Goethe R., et al. (2011). Differential proteome analysis of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis grown in vitro and isolated from cases of clinical Johne's disease. Microbiology 157(Pt 2), 557–565. 10.1099/mic.0.044859-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiśniewski J. R., Zougman A., Nagaraj N., Mann M. (2009). Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat. Methods 6, 359–362. 10.1038/nmeth.1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittekindt N. E., Padhi A., Schuster S. C., Qi J., Zhao F., Tomsho L. P., et al. (2010). Nodeomics: pathogen detection in vertebrate lymph nodes using meta-transcriptomics. PLoS ONE 5:e13432. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe A. J. (2005). The acetate switch. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69, 12–50. 10.1128/MMBR.69.1.12-50.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe L. M., Veeraraghavan U., Idicula-Thomas S., Schürer S., Wennerberg K., Reynolds R., et al. (2013). A chemical proteomics approach to profiling the ATP-binding proteome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 1644–1660. 10.1074/mcp.M112.025635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo H. M., Noack S., Seibold G. M., Willbold S., Eikmanns B. J., Bott M. (2010). Link between phosphate starvation and glycogen metabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum, revealed by metabolomics. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 6910–6919. 10.1128/AEM.01375-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ReesLFQ.xlsx.

ReesDiMet.xlsx.

Fasta files whole sequence predicted proteomes of all isolates.

MS/MS spectra of galactokinase SNP.