Abstract

Alcohol is a risk factor for communicable and noncommunicable diseases, and alcohol consumption is rising steadily in India. The growth of multinational alcohol corporations, such as Diageo, contributes to India’s changing alcohol environment.

We provide a brief history of India’s alcohol regulation for context and examine Diageo’s strategies for expansion in India in 2013 and 2014. Diageo is attracted to India’s younger generation, women, and emerging middle class for growth opportunities.

Components of Diageo’s responsibility strategy conflict with evidence-based public health recommendations for reducing harmful alcohol consumption. Diageo’s strategies for achieving market dominance in India are at odds with public health evidence. We conclude with recommendations for protecting public health in emerging markets.

In India, average adult per capita alcohol consumption increased by 19% from 2005 to 2010.1 In 2010, alcohol consumption ranked among the country’s top 10 leading risk factors for causes of death (350 000 deaths), disability-adjusted life years (n = 14.2 million), and years of life lost (n = 11 million).2 In a population of 1.2 billion,3 approximately 15% of Indians drink alcohol; however, per capita consumption among Indian drinkers is approximately 1.5 times greater than the average among drinkers worldwide.1

Alcohol consumption in India is an immediate public health concern, given the national burden of communicable diseases and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). Each year, one quarter of the world’s incident cases of tuberculosis are in India,4 and because of shifting demographic and socioeconomic factors, NCDs now contribute to half of the country’s deaths.5 Indian studies have documented that alcohol consumption is associated with both communicable diseases and NCDs, including HIV,6–8 tuberculosis,9,10 and cancers,11 as well as violence12,13 and injuries.14,15

With this imminent public health crisis and links between industry tactics and public health problems,16–18 there is a need to better understand the role of the global alcohol industry in India’s changing alcohol environment. We provide a brief history of India’s alcohol regulations to contextualize the current alcohol environment. Diageo, the world’s largest spirits marketer, made significant investments in India’s alcohol market between May 2013 and July 2014, and we examine its growth as a case study. We assess how the principal elements of Diageo’s “responsibility strategy” compare with evidence-based public health recommendations for reducing harmful alcohol consumption. We conclude with recommendations for promoting and protecting public health.

Opportunities to obtain internal alcohol industry documents or firsthand accounts of its practices are rare, making it challenging to understand its intentions; therefore, we relied on a comprehensive review of sources such as media articles or annual reports over a defined time period. To monitor Diageo’s activities in India, the first author read online media articles for 18 months (July 2013–December 2014), compiled with Google News Alerts related to the following keywords: “alcohol in India,” “alcohol consumption in India,” “Diageo in India,” and “spirits in India.” The News Alerts generated approximately 1500 articles from various regions of the world (e.g., India, the United Kingdom, and the United States), some of which covered similar ground. The same author also monitored alcohol industry–oriented market research such as just-drinks.com.19 We collected additional information from Diageo’s Web site and its 2014 fiscal year annual report.20 We also searched other alcohol industry Web sites, including the International Center for Alcohol Policies (ICAP) main site21 as well as other ICAP sites.22,23 We drew on reviews of the alcohol policy research literature to identify evidence-based policies to compare with Diageo’s responsibility strategy.24–30

OVERVIEW OF ALCOHOL CONTROL IN INDIA

A detailed account of India’s history of alcohol consumption and the drinking culture has been written elsewhere.31 In brief, historically, the prevalence of alcohol consumption in India was relatively low32 and there were restrictions on who could drink and when drinking was permitted.33 During the early 19th century, India became more industrially developed, and, like the upper class, members of the growing middle class abstained from alcohol to distinguish themselves from the lower classes.31 Alcohol consumption in India became more popular during the British colonial period,33 and 1862 saw the establishment of India’s first alcohol manufacturing distillery.34 Alcohol became an important source of revenue for the colonial government with the implementation of the Bombay Abkari Act of 1878 and the Mhowra Act of 1892, which taxed the production of toddy, a locally produced alcoholic beverage, and prohibited other locally produced alcoholic drinks.35

In 1937, several Indian states enacted policies prohibiting alcohol, although the bans were abolished during World War II and alcohol excise taxes became the country’s largest source of government revenue.36 Influenced by Mohandas Gandhi’s temperance movement,37 alcohol control was included in one of the Directive Principles of State Policy under Article 47 of the Constitution of India, giving states control over alcohol policies.38 However, the central (i.e., national) Indian government formulated a plan to achieve national prohibition by 1958, causing several states to temporarily reintroduce alcohol prohibition. With economic and political changes in the mid-1960s, the ruling upper class became less supportive of prohibition policies; thus, by 1971, all states lifted the alcohol bans, except Gujarat.36 By the late 1960s, social stigma against the liquor market had largely diminished.36 In the 1990s, in the context of a general move toward market liberalization, India permitted the global alcohol industry to enter its alcohol market.33

Today, alcohol policies and alcohol markets vary across India’s 29 states.39 There is a national blood alcohol concentration limit of 0.03 grams per deciliter for drivers; however, the level of enforcement of drink-driving policies is perceived to be low.40 As of 2014, 4 states and 1 Union Territory had total bans on alcohol and several others had partial prohibition (e.g., bans on the production or consumption—or both—of specific types of alcohol),39 although alcohol policies in Indian states change frequently over time.41 Most recently, in 2014, the southern state of Kerala considered taking steps to achieve total alcohol prohibition but weakened the proposed policy regulations at the end of the year.42 Prohibition policies appear to have greater effects on female than male consumption,43 but precise measurement of alcohol use in India is difficult because 44% to 50% of alcohol consumption is unrecorded, with even greater proportions in rural areas.1,44,45 Unrecorded alcohol generally refers to alcohol produced at home or informally, alcohol legally imported for personal use, and alcohol illicitly imported.46 Such beverages are usually cheaper than recorded alcohol, as they evade taxes.47

INDIA’S CHANGING ALCOHOL MARKET

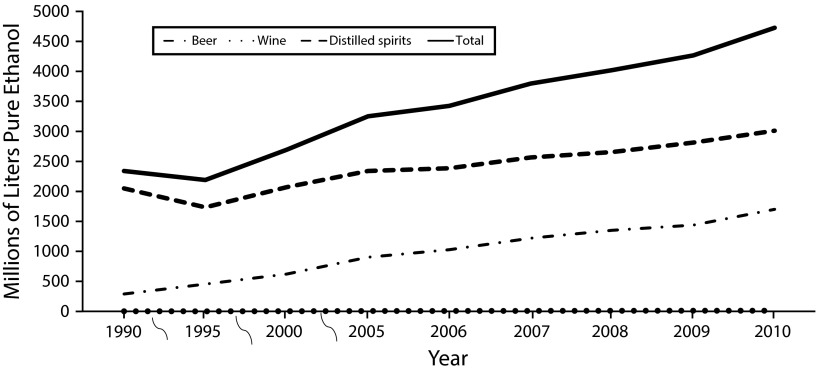

Despite the large proportion of unrecorded alcohol in India,44,47 the global alcohol industry is gaining prominence in the recorded, or formal, alcohol market.31,39 Data from a leading global market research firm serving the alcohol industry indicate that India is now among the top 10 countries worldwide for alcohol sales, after experiencing consistent increases in the past decade (Figure 1).48 From 1990 to 2010, the liters of pure ethanol sold in the form of spirits increased by 147% and in the form of beer by 587%. By 2011, spirits accounted for nearly two thirds of the country’s alcohol consumption.48 International Wine and Spirits Research data suggest that between 2009 and 2013, the compound annual growth rate increased for imported alcoholic beverages but decreased for domestic alcoholic beverages.49

FIGURE 1—

Trends in alcohol consumption, by beverage type and total consumed: India, 1990–2010.

Source. Impact Databank.48

DIAGEO AND INDIA

Diageo, a London-based multinational alcohol corporation, describes itself as “the leading premium spirits business in the world.”50 In 2010, the company had net revenue of $15 billion and a ratio of profit to revenue of 25%.48 Diageo has taken numerous steps to speed its growth in emerging markets. An online industry news article stated that in 2008, emerging markets accounted for approximately 25% of Diageo’s sales by volume; by June 2014, that figure was roughly 65%.51 However, some of its growth has involved illegal activities: in July 2011, the US Securities and Exchange Commission charged Diageo with major violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.52 According to the US government media release, for 6 years, starting in 2003, Diageo illicitly paid more than US $1.7 million to hundreds of Indian government officials. The Indian officials

were responsible for purchasing or authorizing the sale of its beverages in India, and increased sales from these payments yielded more than $11 million in profit for the company.52

There were also similar charges for violations in Thailand and South Korea. Diageo paid more than US $16 million in fines to the US government to settle the investigation.52

In 2010, India's United Spirits Limited (USL) sold 12.7% of the world’s top 100 brands of spirits (by volume). Globally, Diageo ranked second, selling 10.8%; however, Diageo was the largest global marketer of spirits when all spirits brands are considered.48 Diageo has expanded its involvement in the production, marketing, and distribution of alcoholic beverages in India through a series of transactions to increase its shareholding in USL, starting with a purchase of 10.04% of its shares in May 2013 (Table 1).20 In July 2013, Diageo acquired another 14.98%. These acquisitions of slightly more than one quarter of the USL shares made Diageo the largest USL shareholder,53 at a combined cost of 52.3 billion Indian rupees (Rs) (approximately US $859 million).20 According to the company’s Asia-Pacific president, starting in October 2013, Diageo hoped that through the USL network it would bring in 5 billion Rs (approximately US $82.5 million) per year.54 With additional acquisitions of 1.35% of the shares in November 2013 and 2.41% of the shares in January 2014, Diageo closed the 2014 fiscal year with 28.78% of shareholdings in USL, after investing a combined total of 65.7 billion Rs (nearly US $1.1 billion; Table 1).20

TABLE 1—

Diageo’s Investments in United Spirits Limited (USL): India, May 2013–June 2014

| Cost |

|||||

| Date of Finalized Transaction | % of Shares in USL | No. of Shares (Millions) | Price per Share (Indian Rupees) | Billions of Indian Rupees | Approximate Equivalent in US $ |

| May 13 and 27, 2013 | 10.04 | 14.59 | 1440 | 21.0 | 344.5 million |

| July 4, 2013 | 14.98 | 21.77 | 1440 | 31.3 | 513.7 million |

| November 26, 2013 | 1.35 | 1.97 | 2400 | 4.7 | 77.2 million |

| January 31, 2014 | 2.41 | 3.50 | 2474 | 8.7 | 142.7 million |

| Total at close of 2014 fiscal year (June 30, 2014) | 28.78 | 41.83 | 65.7 | 1.1 billion | |

Source. Diageo 2014 Annual Report.20(p102)

Holding more than a quarter of the USL shares, Diageo was not yet done investing in USL: in April 2014, Diageo offered approximately US $1.9 billion for an additional 26% of USL’s shares, in hopes of becoming the majority shareholder.55 This agreement was finalized on July 2, 2014. In Diageo’s annual report, the chief executive, Ivan Menezes, stated,

By acquiring an additional 26% of United Spirits Limited (USL) on 2 July 2014, taking our shareholding to a majority holding of 54.78%, we have taken a leadership position in India which will provide a transformational platform for growth in this very attractive spirits market. We will consolidate USL from the start of fiscal 2015, and with our combined strength, the Indian market will become one of Diageo’s largest markets next year and a major contributor to our growth ambitions.20(p15)

According to Menezes, most countries contribute 3% or less to Diageo’s revenue, but the company anticipates drawing up to 10% of its revenue from India through USL’s 65 000 outlets reaching 90% of the country.56 However, Diageo must confront regulatory factors in India, such as taxation57 and other regulatory systems that differ from state to state, as well as a national ban on broadcast alcohol advertising.39 The managing director of Diageo India, Abanti Sankaranarayanan, acknowledges the unique regulatory alcohol environment, but explains that Diageo is “harnessing the opportunity that India has.”58

INDIA’S DEMOGRAPHIC AND SOCIOECONOMIC FACTORS

India has many characteristics that are appealing to multinational alcohol corporations such as Diageo. Accounting for 17% of the world’s population, India is the world’s second most populous country.3 Social norms regarding alcohol use are changing and alcohol is becoming more culturally accepted.33,59 India’s population is relatively young, with years of potential alcohol consumption ahead of them. One 2003 study found that Indians had started drinking at younger ages; the average age of drinking initiation dropped from 25 years in 1988 to 20 years in 2002.44 A recent study in the Indian state of Goa found a threefold increase in reported alcohol consumption during adolescence among males born in the early 1980s compared with those born in the late 1950s.60

A growing body of global research shows that the alcohol industry uses strategic alcohol marketing and packaging to attract new, young consumers,24,61–63 and Diageo is no exception.18,64 In 2006, USL introduced the sale of alcohol in small sachets, or “tetra-paks,” which rapidly became popular.65 Following on the success of these sachets in India, USL and Diageo are now distributing their brands in mini-bottles (50–90 mL).66 Tetra-paks and mini-bottles are affordable and easy to conceal, and research among African university students has found that they have potential appeal to young consumers.67 Additionally, Diageo India is introducing Smirnoff Black Ice; Diageo India’s marketing director, Bhavesh Somaya, says that “Ice has a much bigger footprint and will focus on recruiting people who are migrating from beer to spirits.”68 Youths have previously been found to be attracted to these ready-to-drink Smirnoff alcoholic beverages.18 Diageo is also reaching younger consumers by selling its alcoholic beverages at community events, such as music festivals. As Diageo’s 2014 annual report states,

Diageo India continued to deliver strong double digit net sales growth as it benefited from having its brands sold through the sales agency agreement with USL. . . . Smirnoff net sales grew high single digit benefiting from its partnership with several music festivals.20(p39)

Diageo also won a spot on the Sahara Force India Formula 1 racing car,69 which is likely to increase exposure of its brands among young fans.

In addition to the younger generations, an increasing proportion of Indian women are consuming alcohol.70 In a media interview, Somaya noted that the rising alcohol consumption among women provides Diageo with growth opportunities and said,

That is a target segment we need to keep in mind and ensure that our brands get more bilingual and speak to both sets of audiences, not just be male-centric.71

With the maturation of many developed markets, global alcohol companies have shifted their efforts to countries with growing economies, where people have increasing amounts of disposable income.24,72 India is one of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), a group of countries with rapidly growing economies. The alcohol industry recognizes the high profit potential in these emerging markets.24,73 In a 2014 media interview, Diageo Chief Executive Menezes said that India’s middle class is expected to consume 42% of the total alcohol consumed by 2015 and 60% by 2025, making an attractive market for Diageo in India.74 Diageo’s 2014 annual report summarizes its vision for growth in Asia:

Our strategy focuses on the highest growth categories and consumer opportunities, driving continued development of super and ultra premium scotch, and leveraging the emerging middle class opportunity through a combination of organic growth and selective acquisitions.20(p38)

DIAGEO’S “RESPONSIBILITY STRATEGY”

The alcohol industry, including Diageo, has in recent years created social aspects and public relations organizations and “responsibility” programs, as they seek to build partnerships with government leaders and public health professionals—and increase their political clout.75,76 Diageo states that it supports public health initiatives being undertaken by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations to reduce harmful drinking; on its Web site it declares,

In May 2013, the UN adopted a Global Monitoring Framework with a target of reducing mortality from NCDs, including heart disease, cancer, chronic respiratory disease and diabetes, by 25% by 2025, with many associated targets, including reducing harmful alcohol consumption by 10%. Diageo shares this goal: every responsible drinking programme we support, every partnership we forge, and every campaign we run is in service of this. We support the balanced and pragmatic approach addressed by the WHO Global Alcohol Strategy and the UN’s NCD framework, and seek to work with member states and other stakeholders to achieve these goals.77

However, in general, alcohol industry responsibility efforts have often focused on less effective interventions to reduce harmful drinking, shifting the focus from more solidly evidence-based public health approaches.75,78–82 Even the familiar “drink responsibly” messages funded by the alcohol industry have been found to be ambiguous and can serve to promote corporate interests.83,84

Diageo has funded 16 social aspect organizations in 15 different countries,77 has developed more than 370 programs in at least 50 countries, and claims that these are designed to address alcohol misuse.85 In searching Diageo20,77,86 and broader alcohol industry sources,21–23 we found limited detailed information on Diageo programs; however, closer examination of the information that is available on these programs raises serious questions about their purpose and effectiveness.

Diageo’s Programs to Address Alcohol Misuse

An analysis of Diageo’s programs developed to reduce alcohol misuse corroborates the existing evidence from Africa, Latin America, and the United Kingdom, demonstrating that industry-funded organizations and research undermine public health.16,78,80–82,87 Diageo’s programs fall into categories such as preventing excessive drinking and reducing drink driving, although components of these programs seem to be at odds with leading public health recommendations (Table 2). Diageo’s Web site indicates that its approach to preventing excessive drinking

ranges from funding advertising campaigns that raise awareness of the risks of binge drinking, to supporting the medical profession in identifying and helping problem drinkers.85

The most effective public health policies for reducing excessive drinking1,24,88 are entirely missing from its program description.

TABLE 2—

Differences Between Diageo’s Programs in India and Public Health Recommendations

| Components of Selected Diageo Programs | Public Health Recommendations1,24,88 |

| “Preventing excessive drinking: This ranges from funding advertising campaigns that raise awareness of the risks of binge drinking, to supporting the medical profession in identifying and helping problem drinkers.”85 | Implement environmental strategies that: Increase the price of alcohol25,89,90; Reduce alcohol’s availability27,28,91; Reduce exposure to alcohol marketing.24,30,88 |

| “Tackling drink driving: We support many initiatives with public and private partners to reduce drink driving through education initiatives, free rides and enforcement campaigns.”85 | Implement: A national drink-driving law that includes a maximum legal blood alcohol concentration limit (e.g., 0.05 g/dL or lower); Sobriety checkpoints and random breath testing.29,40,92,93 |

| “DRINKiQ: Diageo also promotes responsible drinking through the DRINKiQ website and courses. Available in nine languages, with 22 specific country pages, DRINKiQ.com aims to raise the ‘collective drink IQ’ by increasing public awareness of the effects of alcohol. Courses aim to broaden understanding of alcohol issues and share tips for responsible drinking. More than 15,000 people have trained with DRINKiQ, including hospitality industry trainers, students, traffic police, bus drivers, members of the lifestyle media and professional sports clubs.”85 | Evaluate programs for effectiveness before widely implementing them and implement programs based on evidence of effectiveness.94,95 (No evaluations of DRINKiQ’s effectiveness were found in a comprehensive search of the literature.) Modify the alcohol environment through population-level interventions (as described in the first category of this column: “Implement environmental strategies”) because education-based approaches have been found to be less effective at changing drinking behaviors.24 |

Diageo’s description of its programs to prevent excessive drinking emphasizes individual-level interventions.85 By contrast, there is strong consensus among public health researchers about the effectiveness of population-level strategies, such as raising the price of alcohol by increasing alcohol taxes,25,89,90 decreasing availability by regulating alcohol outlet density and reducing days and hours of alcohol sales,27,28,91 and reducing exposure to alcohol marketing.24,30,88 Developing countries are more vulnerable to accepting alcohol industry offers to partner in tackling harmful alcohol consumption, as they generally have weak enforcement of alcohol control policies.72,96 This is problematic because Diageo’s focus on individual-level behavior change distracts from the implementation of effective public health policies that modify the alcohol environment to reduce harmful drinking.72 Partnering with leaders in developing countries provides Diageo with opportunities to make its brands known in societies and to promote less effective alcohol control policies before stronger policies can be implemented.96

Another Diageo initiative is the implementation of drink-driving prevention programs in developing countries,85 including the recent launch of a 30-city program in India.97 Diageo’s Web site indicates that its drink-driving programs include “education initiatives, free rides, and enforcement campaigns.”85 In an online news article, Managing Director Sankaranarayanan described the project in India as including

training and capacity building of enforcement agencies like the traffic police, distribution of high quality breath alcohol analyzers, training drivers of commercial vehicles and creating awareness among university students.98

On the basis of Diageo’s descriptions of its drink-driving programs,85,98 it appears that the programs include strategies with less evidence of effectiveness for reducing drink driving and fail to include evidence-based effective interventions (Table 2); another study that reviewed 408 alcohol industry initiatives from around the world reached similar conclusions.99 Studies have found limited evidence of effectiveness regarding educational initiatives and designated-driver programs.24,100,101 Moreover, there is no evidence indicating that the distribution of breath alcohol analyzers will reduce drink driving in a country such as India, where there is a high level of perception that corruption exists in the public sector and that most of the population engages in bribery.102 Furthermore, awareness-raising initiatives will most likely be ineffective in reducing drink driving unless they meet several criteria (e.g., adequate audience exposure, implemented in addition to other prevention interventions)26; necessary information is not available to critically evaluate Diageo’s campaigns. Diageo’s drink-driving programs do not seem to promote the public health prevention strategies that have strong evidence of effectiveness, such as countrywide sobriety checkpoints and random breath testing that can result in penalties for those found to have a blood alcohol concentration above India’s legal limit of 0.03 grams per deciliter.29,40,92,93

Diageo also globally promotes its online responsible-drinking program titled DRINKiQ, although the extent to which it is promoted in India is unknown. As described on its Web site, DRINKiQ “aims to raise the ‘collective drink IQ’ by increasing public awareness of the effects of alcohol” (Table 2).85 Programs funded by the alcohol industry, such as DRINKiQ, are not typically evaluated.18 We sought information on DRINKiQ’s effectiveness by searching for “DRINKiQ” or “Diageo” in 9 databases, including the alcohol industry’s own research database (www.drinksresearch.org), but we were unable to find evaluative studies. In public health practice, it is recommended that programs first be evaluated for effectiveness, and receive wide implementation only if there is evidence of effectiveness.94,95

Plan W

Given Diageo’s stated hope of promoting greater alcohol consumption among women,71 and global evidence that as income rises, alcohol consumption increases,103 it is also of interest that in 2012, Diageo launched Plan W, “a community investment programme that aims to empower women through learning.”104 As of March 2014, Diageo had 32 initiatives in a dozen markets in the Asia Pacific region,104 and by June 2014, its Plan W initiatives had reached more than 57 000 women and 19 500 men.86 The corporation implemented 2 Plan W pilot programs in India in 2014, one in Bangalore and the other in New Delhi, to train women in technical and life skills.105 By 2017, Diageo aims to “empower” 2 million women in the Asia Pacific.105

PROMOTING PUBLIC HEALTH

This case study provides insight into the global alcohol industry’s strategies for growth in emerging markets through the documentation of Diageo’s recent activities in India; however, it does not provide causal evidence that Diageo India’s practices will lead to increases in alcohol consumption. Nonetheless, this case study increases awareness of the potential discordance between industry practices and public health evidence and priorities, and sheds light on ways that public health professionals can help to prevent the alcohol industry from leading the public health agenda around the world.

First, as others have advocated,75,78 researchers should monitor and document the alcohol industry’s efforts to involve itself in public health. Cumulatively, the research community can enhance awareness of the conflicted nature of industry-funded programs and research. Second, public health professionals should advocate for health policies based on unbiased evidence of effectiveness and encourage government leaders to be wary of industry-funded initiatives. Third, the WHO and other international organizations should endorse conflict-of-interest standards for alcohol companies similar to those recommended for the tobacco industry106 and provide capacity development training to countries to guide them in deflecting overtures of partnership with the industry, thereby decreasing their vulnerability to the public health threats associated with industry-sponsored assistance; however, this is indisputably challenging unless more resources are made available. Additional research on the globalization of the alcohol industry and the intersection with public health is critical for preventing a rising tide of health and social problems resulting from harmful alcohol consumption.

Acknowledgments

M. B. Esser received funding from the Department of Health, Behavior and Society at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Human Participant Protection

Protocol approval was not necessary because the study did not involve human research participants.

References

- 1.Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD arrow diagram. 2013. Available at: http://www.healthdata.org/data-visualization/gbd-arrow-diagram. Accessed September 26, 2014.

- 3.Government of India. Census Info India. 2011. Available at: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/censusinfodashboard/index.html. Accessed September 15, 2014.

- 4.TB India 2014: Annual Status Report. New Delhi: Central TB Division, Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2014. Available at: www.tbcindia.nic.in/pdfs/TB%20INDIA%202014.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Srinath Reddy K, Shah B, Varghese C, Ramadoss A. Responding to the threat of chronic diseases in India. Lancet. 2005;366(9498):1744–1749. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dandona L, Dandona R, Kumar GA et al. Risk factors associated with HIV in a population-based study in Andhra Pradesh state of India. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37(6):1274–1286. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Go VF, Solomon S, Srikrishnan AK et al. HIV rates and risk behaviors are low in the general population of men in southern India but high in alcohol venues: results from 2 probability surveys. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(4):491–497. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181594c75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverman JG, Raj A, Cheng DM et al. Sex trafficking and initiation-related violence, alcohol use, and HIV risk among HIV-infected female sex workers in Mumbai, India. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(suppl 5):S1229–S1234. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pednekar MS, Sansone G, Gupta PC. Association of alcohol, alcohol and tobacco with mortality: findings from a prospective cohort study in Mumbai (Bombay), India. Alcohol. 2012;46(2):139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajeswari R, Chandrasekaran V, Suhadev M, Sivasubramaniam S, Sudha G, Renu G. Factors associated with patient and health system delays in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in south India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6(9):789–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gajalakshmi V, Hung RJ, Mathew A, Varghese C, Brennan P, Boffetta P. Tobacco smoking and chewing, alcohol drinking and lung cancer risk among men in southern India. Int J Cancer. 2003;107(3):441–447. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babu BV, Kar SK. Domestic violence in eastern India: factors associated with victimization and perpetration. Public Health. 2010;124(3):136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nayak MB, Patel V, Bond JC, Greenfield TK. Partner alcohol use, violence and women’s mental health: population-based survey in India. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(3):192–199. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.068049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Das A, Gjerde H, Gopalan SS, Normann PT. Alcohol, drugs, and road traffic crashes in India: a systematic review. Traffic Inj Prev. 2012;13(6):544–553. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2012.663518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benegal V. Alcohol and injuries: India. In: Cherpitel C, Giesbrecht N, Hungerford D, editors. Alcohol and Injuries: Emergency Department Studies in an International Perspective. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. pp. 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babor TF, Robaina K, Jernigan D. The influence of industry actions on the availability of alcoholic beverages in the African region. Addiction. 2015;110(4):561–571. doi: 10.1111/add.12832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jahiel RI, Babor TF. Industrial epidemics, public health advocacy and the alcohol industry: lessons from other fields. Addiction. 2007;102(9):1335–1339. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mosher JF. Joe Camel in a bottle: Diageo, the Smirnoff brand, and the transformation of the youth alcohol market. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):56–63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Just-Drinks. Aroq Ltd, 2014. Available at: http://www.just-drinks.com. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- 20.Diageo. Diageo Annual Report 2014. 2014. Available at: http://www.diageo.com/en-row/newsmedia/Pages/reports.aspx. Accessed September 11, 2014.

- 21.International Center for Alcohol Policies (ICAP) Welcome to ICAP. 2014. Available at: http://www.icap.org. Accessed October 14, 2014.

- 22.International Center for Alcohol Policies. Beer, wine and spirits producers’ commitments to reduce harmful drinking. 2014. Available at: http://www.producerscommitments.org/default.aspx. Accessed May 19, 2015.

- 23.International Center for Alcohol Policies. Global actions on harmful drinking: India. 2014. Available at: http://www.global-actions.org/Countries/India/Overview/tabid/346/Default.aspx. Accessed October 14, 2014.

- 24.Babor TF, Caetano R, Casswell S . Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elder RW, Lawrence B, Ferguson A et al. The effectiveness of tax policy interventions for reducing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(2):217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elder RW, Shults RA, Sleet DA et al. Effectiveness of mass media campaigns for reducing drinking and driving and alcohol-involved crashes: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(1):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hahn RA, Kuzara JL, Elder R et al. Effectiveness of policies restricting hours of alcohol sales in preventing excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(6):590–604. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Middleton JC, Hahn RA, Kuzara JL et al. Effectiveness of policies maintaining or restricting days of alcohol sales on excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(6):575–589. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shults RA, Elder RW, Sleet DA et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce alcohol-impaired driving. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(4 suppl):66–88. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson P, de Bruijn A, Angus K, Gordon R, Hastings G. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44(3):229–243. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benegal V. India: alcohol and public health. Addiction. 2005;100(8):1051–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Room R, Janca A, Bennett LA, Schmidt L, Sartorius N. WHO cross‐cultural applicability research on diagnosis and assessment of substance use disorders: an overview of methods and selected results. Addiction. 1996;91(2):199–220. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.9121993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saxena S. Country profile on alcohol in India. In: Riley L, Marshall M, editors. Alcohol and Public Health in 8 Developing Countries. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999. pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desai N, Nawamongkolwattana B, Ranaweera S, Man Shrestha D, Sobhan MA. Get High on Life Without Alcohol. New Delhi, India: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saldanha IM. On drinking and “drunkenness”: history of liquor in colonial India. Econ Polit Wkly. 1995;30(37):2323–2331. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reddy DN, Patnaik A. Anti-arrack agitation of women in Andhra Pradesh. Econ Polit Wkly. 1993;28(21):1059–1066. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blocker JS, Fahey DM, Tyrrell IR. Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History: A Global Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Constitution of India: Seventh Schedule. New Delhi: Government of India; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alcohol Marketing and Regulatory Policy Environment in India. New Delhi, India: Public Health Foundation of India; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Global Status Report on Road Safety, 2013: Supporting a Decade of Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rahman L. Alcohol Prohibition and Addictive Consumption in India. London: UK: London School of Economics; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42.India’s Kerala state dilutes alcohol ban. BBC News. 2014. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-30544717. Accessed January 9, 2015.

- 43.Subramanian SV, Nandy S, Irving M, Gordon D, Davey Smith G. Role of socioeconomic markers and state prohibition policy in predicting alcohol consumption among men and women in India: a multilevel statistical analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(11):829–836. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benegal V, Gururaj G, Murthy P. WHO Collaborative Project on Unrecorded Consumption of Alcohol: Karnataka, India. Bangalore, India: National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences; 2003. Available at: http://www.nimhans.kar.nic.in/cam/html/publications.html. Accessed September 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chakrabarti A, Rai TK, Sharma B, Rai BB. Culturally prevalent unrecorded alcohol consumption in Sikkim, North East India: cross-sectional situation assessment. J Subst Use. 2015;20(3):162–167. [Google Scholar]

- 46.International Guide for Monitoring Alcohol Consumption and Related Harm. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rehm J, Kailasapillai S, Larsen E et al. A systematic review of the epidemiology of unrecorded alcohol consumption and the chemical composition of unrecorded alcohol. Addiction. 2014;109(6):880–893. doi: 10.1111/add.12498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Impact Databank. The Global Drinks Market: Impact Databank Review and Forecast, 2011 Edition. New York, NY: M. Shanken Communications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitra S. Indians High on Imported Spirits. New Delhi, India: Business Standard; 2014; Available at: http://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/indians-high-on-imported-spirits-114081300885_1.html. Accessed September 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diageo. Spirits. 2014. Available at: http://www.diageo.com/en-row/ourbrands/categories/spirits/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed September 11, 2014.

- 51.Hopkins A USL takeover gives Diageo “unassailable” position. The Spirits Business. 2014. Available at: http://www.thespiritsbusiness.com/2014/06/usl-takeover-gives-diageo-unassailable-position. Accessed September 11, 2014.

- 52.US Securities and Exchange Commission. SEC charges liquor giant Diageo with FCPA violations. 2011. Available at: http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2011/2011-158.htm. Accessed September 19, 2014.

- 53.Wehring O. INDIA/UK: Diageo takes control of United Spirits with further stake buy. Aroq Ltd. 2013. Available at: http://www.just-drinks.com/news/diageo-takes-control-of-united-spirits-with-further-stake-buy_id110806.aspx. Accessed September 11, 2014.

- 54.Madonna A. Diageo charts roll-out plans with United Spirits. Business Standard. 2013. Available at: http://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/diageo-charts-roll-out-plans-with-united-spirits-113092400857_1.html. Accessed September 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bray C. Diageo makes new bid for controlling stake in United Spirits of India. New York Times. 2014 Available at: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2014/04/15/diageo-makes-new-bid-for-controlling-stake-in-united-spirits-of-india/?_php=true&_type=blogs&_r=0. Accessed September 11, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Badrinath R, Madonna A. Diageo aims for 10% revenue from India. Business Standard. 2014 Available at: http://www.business-standard.com/article/companies/diageo-aims-for-10-revenue-from-india-114032400997_1.html. Accessed September 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Why Indian alcohol market is not in high spirits. Business World. 2015 Available at: http://cdn.bwbusinessworld.com/co-report/why-indian-alcohol-market-not-high-spirits#sthash.zWUB6HkU.dpbs. Accessed July 14, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agarwal S. About 40% of our luxury growth comes from non-metros: Diageo India MD. Live Mint. 2014. Available at: http://www.livemint.com/Companies/DWjkzNvk3pN9jix11JY36N/About-40-of-our-luxury-growth-comes-from-nonmetros-Diageo.html. Accessed June 9, 2015.

- 59.Prasad R. Alcohol use on the rise in India. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):17–18. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61939-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pillai A, Nayak M, Greenfield T, Bond JC, Hasin DS, Patel V. Adolescent drinking onset and its adult consequences among men: a population based study from India. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(10):922–927. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hastings G. “They’ll Drink Bucket Loads of the Stuff”: An Analysis of Internal Alcohol Industry Advertising Documents. Stirling, UK: Alcohol Education and Research Council; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ross C, Ostroff J, Jernigan D. Evidence of underage targeting of alcohol advertising on television in the United States: lessons from the Lockyer v. Reynolds decisions. J Public Health Policy. 2014;35(1):105–118. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2013.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ross CS, Ostroff J, Siegel MB, DeJong W, Naimi TS, Jernigan DH. Youth alcohol brand consumption and exposure to brand advertising in magazines. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75(4):615–622. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nicholls J. Everyday, everywhere: alcohol marketing and social media—current trends. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;47(4):486–493. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/ags043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dalal M. Tetra Pak emerging as preferred packing for alcohol in Karnataka. Live Mint. 2013. Available at: http://www.livemint.com/Industry/D2HAiol3V8A57JoquKUzwJ/Tetra-Pak-emerging-as-preferred-packing-for-alcohol-in-Karna.html. Accessed October 14, 2014.

- 66.Dhamija A, Sarkar J. Now, booze comes in affordable packs. Times of India. 2013 Available at: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/Now-booze-comes-in-affordable-packs/articleshow/27324427.cms. Accessed September 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mwele JK. Perceived impact of packaging on alcohol consumption: a case of the University of Nairobi students. University of Nairobi. 2009. Available at: http://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/13267. Accessed October 21, 2014.

- 68.Dhamija A. Diageo breezes into RTD battle. Times of India. 2014 Available at: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/Business/India-Business/Diageo-breezes-into-RTD-battle/articleshow/44904642.cms. Accessed October 23, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wehring O. INDIA: Smirnoff joins Johnnie Walker on Diageo’s Formula One podium. Aroq Ltd. 2014. Available at: http://www.just-drinks.com/news/smirnoff-joins-johnnie-walker-on-diageos-formula-one-podium_id113573.aspx. Accessed September 15, 2014.

- 70.Benegal V, Nayak M, Murthy P, Chandra P, Gururaj G. Women and alcohol in India. In: Obot IS, Room R, editors. Alcohol, Gender and Drinking Problems: Perspectives From Low and Middle Income Countries. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. pp. 89–124. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dutta S. Sipping success. IMPACT. 2014. Available at: http://www.impactonnet.com/Sipping-success. Accessed September 15, 2014.

- 72.Caetano R, Laranjeira R. A “perfect storm” in developing countries: economic growth and the alcohol industry. Addiction. 2006;101(2):149–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jernigan DH. The global alcohol industry: an overview. Addiction. 2009;104(suppl 1):6–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dhamija A, Kurian B. New middle class will form 60% of business: Diageo CEO. Times of India. 2014 Available at: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/Business/India-Business/New-middle-class-will-form-60-of-business-Diageo-CEO/articleshow/40862744.cms. Accessed September 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anderson P. The beverage alcohol industry’s social aspects organizations: a public health warning. Addiction. 2004;99(11):1376–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miller PG, de Groot F, McKenzie S, Droste N. Vested interests in addiction research and policy. Alcohol industry use of social aspect public relations organizations against preventative health measures. Addiction. 2011;106(9):1560–1567. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Diageo. Alcohol policy. 2014. Available at: http://www.diageo.com/en-row/csr/alcoholinsociety/Pages/alcohol-policy.aspx. Accessed September 11, 2014.

- 78.Jernigan DH. Global alcohol producers, science, and policy: the case of the International Center for Alcohol Policies. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):80–89. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Caetano R. About smoke and mirrors: the alcohol industry and the promotion of science. Addiction. 2008;103(2):175–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Babor TF. Alcohol research and the alcoholic beverage industry: issues, concerns and conflicts of interest. Addiction. 2009;104(suppl 1):34–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McCambridge J, Hawkins B, Holden C. Industry use of evidence to influence alcohol policy: a case study of submissions to the 2008 Scottish government consultation. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4):e1001431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hawkins B, McCambridge J. Industry actors, think tanks, and alcohol policy in the United Kingdom. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(8):1363–1369. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smith SW, Atkin CK, Roznowski J. Are “drink responsibly” alcohol campaigns strategically ambiguous? Health Commun. 2006;20(1):1–11. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc2001_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smith KC, Cukier S, Jernigan DH. Defining strategies for promoting product through “drink responsibly” messages in magazine ads for beer, spirits and alcopops. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Diageo. Programmes to address alcohol misuse. 2014. Available at: http://www.diageo.com/en-row/csr/alcoholinsociety/Pages/programmes-to-address-alcohol-misuse.aspx. Accessed September 11, 2014.

- 86.Diageo. Sustainability & responsibility performance addendum 2014. 2014. Available at: http://www.diageo.com/en-row/NewsMedia/Pages/resource.aspx?resourceid=2316. Accessed September 11, 2014.

- 87.Truen S, Ramkolowan Y, Corrigall J, Matzopoulos R. Baseline study of the liquor industry: including the impact of the National Liquor Act 59 of 2003. DNA Economics. 2011 Available at: http://www.thedti.gov.za/business_regulation/docs/nla/other_pdfs/dna_economics_nla_act.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2234–2246. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wagenaar AC, Salois MJ, Komro KA. Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: a meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction. 2009;104(2):179–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wagenaar AC, Tobler AL, Komro KA. Effects of alcohol tax and price policies on morbidity and mortality: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2270–2278. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.186007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Babor TF, Caetano R. Evidence-based alcohol policy in the Americas: strengths, weaknesses, and future challenges. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2005;18(4–5):327–337. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892005000900013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Peden M, Scurfield R, Sleet D, editors. World Report on Road Traffic Injury Prevention. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Elder RW, Shults RA, Sleet DA, Nichols JL, Zaza S, Thompson RS. Effectiveness of sobriety checkpoints for reducing alcohol-involved crashes. Traffic Inj Prev. 2002;3(4):266–274. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(9):1322–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rychetnik L, Frommer M, Hawe P, Shiell A. Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(2):119–127. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Casswell S. Vested interests in addiction research and policy. Why do we not see the corporate interests of the alcohol industry as clearly as we see those of the tobacco industry? Addiction. 2013;108(4):680–685. doi: 10.1111/add.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.TNN. Karisma Kapoor launched Diageo Road to Safety campaign in Mumbai. Times of India. 2014 Available at: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/events/mumbai/Karisma-Kapoor-launched-Diageo-Road-to-Safety-campaign-in-Mumbai/articleshow/44772700.cms. Accessed October 14, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 98.ET Bureau. Diageo launches road safety programme in India. Economic Times. 2014 Available at: http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2014-09-01/news/53441986_1_traffic-police-international-road-federation-road-safety-programme. Accessed September 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Babor TF, Robaina K. Public health, academic medicine, and the alcohol industry’s corporate social responsibility activities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):206–214. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rivara FP, Relyea-Chew A, Wang J, Riley S, Boisvert D, Gomez T. Drinking behaviors in young adults: the potential role of designated driver and safe ride home programs. Inj Prev. 2007;13(3):168–172. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.015032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ditter SM, Elder RW, Shults RA et al. Effectiveness of designated driver programs for reducing alcohol-impaired driving: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(5 suppl):280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Transparency International. Corruption perceptions index 2013. Available at: http://cpi.transparency.org/cpi2013/results. Accessed December 22, 2013.

- 103.Room R, Jernigan D, Carlini Cotrim B . Alcohol in Developing Societies: A Public Health Approach. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies and World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Diageo. Diageo empowers 40,000 women under Asia Pacific Plan W Programme. 2014. Available at: http://www.diageo.com/en-row/newsmedia/Pages/resource.aspx?resourceid=2176. Accessed September 11, 2014.

- 105.Diageo. Empowering urban women in India—Plan W 2014. Available at. http://www.diageo.com/en-row/csr/casestudies/Pages/empowering-urban-women-in-india-plan-w.aspx. Accessed September 11, 2014.

- 106.World Health Organization. Guidelines for implementation of Article 5.3 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. 2008. Available at: www.WHO.int/fctc/guidelines/article_5_3.pdf. Accessed June 15, 2015.