Abstract

This article highlights the new racial and ethnic diversity in rural America, which may be the most important but least anticipated population shift in recent demographic history. Ethnoracial change is central to virtually every aspect of rural America over the foreseeable future: agro-food systems, community life, labor force change, economic development, schools and schooling, demographic change, intergroup relations, and politics. The goal here is to plainly illustrate how America’s racial and ethnic transformation has emerged as an important dimension of ongoing U.S. urbanization and urbanism, growing cultural and economic heterogeneity, and a putative “decline in community” in rural America. Rural communities provide a natural laboratory for better understanding the implications of uneven settlement and racial diversity, acculturation, and economic and political incorporation among Hispanic newcomers. This article raises the prospect of a new racial balkanization and outlines key impediments to full incorporation of Hispanics into rural and small town community life. Immigration and the new ethnoracial diversity will be at the leading edge of major changes in rural community life as the nation moves toward becoming a majority-minority society by 2042.

Introduction

The conventional view today—usually reinforced by pundits and politicians—is that rural America is made of up mostly of white people of European ancestry. To be sure, the ancestral roots of the peoples populating many parts of the agricultural Midwest today are tied historically to European immigrants from Northern Europe—Germany and the Scandinavian countries. They arrived in the mid-nineteenth century, bypassing congested cities in the East to homestead in the upper Midwest (i.e., Minnesota, Wisconsin, and the Dakotas), where farmland was plentiful and still available for the taking. Other white ethnic groups (e.g., ScotsIrish) settled in smaller towns and rural areas in Appalachia to work in the coal mines, in the timber industry, or on the railroads. Even today, rural people are sometimes considered the “real Americans.”1 They are hardworking, patriotic, self-sufficient, religious, and, of course, white. Others—those living in cities—are somehow different and presumably less American. They also are much less likely to self-identify as white or to be considered white by others.

The demographic reality, of course, is that rural America has been home throughout its history to large numbers of racial and ethnic minorities (Brown and Schafft 2011; Saenz 2012; Summers 1991). America’s rural racial minorities, however, are often geographically and socially isolated from mainstream America and easily forgotten or ignored. They live on remote Indian reservations (Snipp 1989), in southern rural areas and small towns in the so-called black belt (Lichter et al. 2007b; Wimberly and Morris 1997), and in the colonias along the lower Rio Grande valley (Saenz and Torres 2003). Unlike that of rural America’s white ethnic groups, the growth of rural minority populations historically has not always been rooted in voluntary immigration or resettlement. Current racial residential patterns instead are a legacy of slavery, conquest, and racial subjugation (and genocide). Rural minority populations are spatially segregated and invisible in ways not usually found in America’s metropolitan areas with large and densely settled inner-city minority populations. Indeed, many big cities today have “majority-minority” populations (e.g., Detroit, Baltimore, Atlanta, San Antonio), reflecting minority in-migration (from rural areas) along with the centrifugal drift of whites to the suburbs and beyond (Frey 2011; Johnson and Lichter 2010). What is new today is the large-scale movement of Hispanics—America’s largest minority, immigrant, and urban population—into many parts of rural and small town America (Jensen 2006; Kandel and Cromartie 2004; Lichter and Johnson 2006). Growing racial and ethnic diversity has a demographic and economic grip on rural America, now and into the foreseeable future.

My overriding aim is to highlight the new racial and ethnic diversity in rural America over the past decade or two, which is one of the most important and least anticipated demographic changes in recent U.S. history. I have several goals. First, I highlight new patterns of Hispanic in-migration and growth, which have provided economic hope for dying small towns in the Midwest and elsewhere, but have also raised new community challenges. Rural America provides a natural laboratory for better understanding the implications of racial change and diversity. Second, I argue that the uneven growth of rural minorities has contributed to a new urbanization and urbanism of rural America, born of growing cultural and economic heterogeneity, and contributing to a possible “decline in community.” Third, I highlight the unique impediments to full incorporation of rural Hispanics into rural and small town community life. I also raise the prospect of a new racial balkanization and uneven impacts across rural America. Growing ethnoracial diversity in rural areas will be at the leading edge of social and cultural change as the United States moves toward becoming a majority-minority society by 2042 (U.S. Census Bureau 2008).

Racial Diversity and Change: The National Picture

Perhaps the major demographic story from early data releases of the 2010 decennial census has been the rapid change in America’s racial and ethnic populations. The 2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94–171) Summary File provides population data for the purpose of redrawing the boundaries of state legislative districts (Humes, Jones, and Ramirez 2011). Between 2000 and 2010, the Hispanic population increased from 35.3 million to 50.5 million, or 43 percent. Hispanic population growth accounted for more than half of the 27.3 million increase in the total U.S. population (Humes et al. 2011). Hispanics now form the largest ethnoracial minority population in the United States, representing 16 percent of the total population. The white population, by contrast, grew by only 1 percent over the past decade.

Interestingly enough, media attention so far has focused almost entirely on big-city populations, especially the rise in majority-minority states and cities (Morello and Keating 2011) and the “changing face” of childhood, that is, the growth in numbers of minority children (Tavernise 2011). For example, Texas joined California, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, and New Mexico between 2000 and 2010 as a “majorityminority” state having more ethnoracial minorities than non-Hispanic whites (Humes et al. 2011). Of the nation’s 3,143 counties, 348 are at least one-half minority. Most of the 100 largest primary cities (of metropolitan areas) now have majority-minority populations, increasing from 43 in 2000 to 58 in 2010 (Frey 2011). In most cases this resulted from both minority population gains and white population declines. Increases in America’s suburban black population, accompanied by the influx of new immigrant populations (Singer 2004), also have been offset by the accelerated movement—exurbanization—of whites into the opencountryside or unincorporated housing developments at the metropolitan fringe.

Rural and small town America have been largely excluded from these discussions, despite the disproportionate potential influences of new minority populations—especially Hispanics—on small communities. By definition, the addition of each new minority person represents a larger proportionate share of small-town populations than those of heavily populated cities or suburbs. The social, economic, and political implications for rural communities are therefore potentially large, but are typically ignored or downplayed in current public policy debates about immigration reform and the incorporation of new immigrants (Hirschman and Massey 2008; Okamoto and Ebert 2010).

Ethnoracial Diversity and Rural Urbanization

The Chicago School of sociology of the 1920s and 1930s, and Louis Wirth (1938) in particular, focused on the “urban way of life” and the loss of community. The eclipse of community presumably was rooted in new social pathologies, born of population density, occupational heterogeneity, ethnic and ancestral diversity, and fragmenting values and behaviors (Lichter and Brown 2011). Chicago at the time provided a scientific laboratory for uncovering empirically the putative negative effects (e.g., anonymity, anomie, impersonal relationships) of rapid urbanization spawned by in-migration of foreign-born white ethnic groups from agrarian countries (in Europe) and the massive influx of blacks from the agricultural South, which was then being transformed by the mechanization of agricultural production and a political climate of widespread racial subjugation and intolerance (e.g., Jim Crow). In the past, rural “boom town” growth has usually been associated with new energy development in the West (Brown, Dorius, and Krannich 2005), not immigrant influxes. With its conceptual roots located in the Chicago school, most previous rural research of this genre has focused on the economic consequences and community disorganization (e.g., crime and other social pathologies) of rapid population growth (Smith, Krannich, and Hunter 2001).

New immigration and changing racial and ethnic composition in rural America (i.e., Hispanic “boom towns”) now provides evidence of rural urbanization and urbanism, as well as a new interpenetration of rural and urban life in America (Castle, Wu, and Weber 2011; Lichter and Brown 2011). Culturally diverse big cities are often viewed as noisy and congested, politically and economically fragmented, and crimeridden and dangerous. Today’s rural towns in the hinterland representmuch smaller versions of Chicago, 100 years removed. Racial and cultural homogeneity is rapidly giving way to ethnoracial change and diversity and to new concerns about the loss of community.

America’s burgeoning rural Hispanic population is leading the way. Hispanics have been America’s most urbanized ethnic or racial group historically (Fussell 2003). The recent geographic dispersion of urbanorigin Hispanics thus has a potentially large urbanizing effect on rural America, if measured by growing ethnoracial and cultural heterogeneity. Significantly, the growth of new rural immigrant populations reflects the economic decisions of big multinational corporations that link rural communities to the national and global economy. This is relevant to old notions of “mass society” and the replacement of horizontal ties with vertical ties that bind the community to the outside world (Warren 1987). Rural foreign-born in-migrants arguably are cultural carriers who bridge America’s urban and rural populations. The rapid growth of rural minority populations reflects the globalism of labor and a new rural cosmopolitanism (Popke 2011).

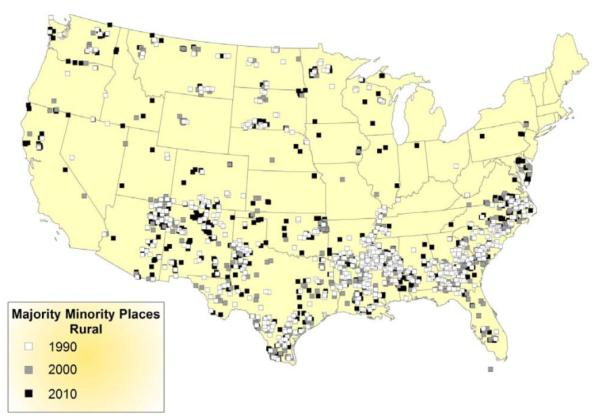

Early results from the recently released 2010 U.S. decennial census indicate that the post-2000 period was one of accelerating rural racial and ethnic diversity. The nonmetropolitan population of racial and ethnic minorities—populations other than non-Hispanic whites— increased from 8.6 to 10.3 million between 2000 and 2010, or by 19.8 percent. Whites hardly grew at all (see Table 1). The rural Hispanic population grew by 44.6 percent during the 2000 to 2010 period, faster than any other racial or ethnic minority (data not shown). In 2010, the size of the nonmetropolitan Hispanic population was 3.8 million, which was nearly identical to the size of the rural black population (4.2 million). Between 2000 and 2010, Hispanics accounted for 56 percent of all nonmetropolitan population growth, yet represented only about 7 percent of its total population in 2010 (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Rural White and Minority Population Distribution, by Metro Status, 2000 and 2010.

| 2000 |

2010 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonmetro | Population | Percent | Population | Percent |

| Non-Hispanic white | 39,765,577 | 82.2 | 40,142,918 | 79.6 |

| Minority | 8,586,502 | 17.8 | 10,284,857 | 20.4 |

| Metro | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 154,787,197 | 66.4 | 156,674,634 | 60.7 |

| Minority | 78,282,630 | 33.6 | 101,643,129 | 39.3 |

Source: 2000 and 2010 U.S. censuses: Summary File 1.

Figure 1.

Minority Shares of Nonmetro Growth, 2000–2010.

The New Racial Mosaic: Geographic Diversity in Hispanic Growth

A recent study of the racial diversity in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan counties (both micropolitan and noncore) showed that the mean percentage of Hispanics in noncore counties increased from 3.9 to 7.0 percent over the 1980 to 2009 period (Lee, Iceland, and Sharp 2011). The least urbanized nonmetropolitan areas (i.e., noncore counties) remained overwhelmingly white—85 percent, on average. Indeed, using the entropy index,2 Lee et al. (2011) reported that metro areas (46.2), on average, were considerably more diverse than micropolitan (33.6) or noncore (25.2) counties. This study also revealed rather similar upward trajectories in racial diversity between 1980 and 2009 in metropolitan, micropolitan, and noncore counties. Between 1980 and 2005–2009, for example, rural diversity (as measured by the entropy index) increased by nearly 40 percent, nearly equaling increases in metropolitan areas. Significantly, ethnoracial diversity has increased slightly more rapidly in the most rural counties than elsewhere since 2000.

Of course, the national demographic picture, viewed through the prism of highly aggregated statistics, risks masking substantial spatial heterogeneity in patterns of Hispanic growth and its social and economic impact. Growing racial and ethnic diversity in the aggregate— even when limited to rural areas—does not necessarily imply that majority and minority populations share the same social or physical space (Johnson and Lichter 2010). In fact, the rural Hispanic population is distributed unevenly and minority populations in general often remain highly segregated in small towns (Lichter et al. 2007a). The new growth of the rural Hispanic population may just as easily reflect a new kind of racial and ethnic balkanization over geographic space, a demographic development suggesting uneven geographic impact, and perhaps growing social distance and greater intolerance between minority and majority populations in some fast-growing rural places (Parisi, Lichter, and Taquino 2011a).

What kind of evidence would suggest the formation of new rural Hispanic enclaves or ghettos? Is there a new balkanization racially across rural communities?

Uneven Distribution of Rural Hispanic Growth

Until recently, the Hispanic population has been heavily concentrated in the Southwest, California, and Texas, as well in a few other major metropolitan gateways, such as New York City, Chicago, and Miami (Massey and Capoferro 2008). Immigration was a regional rather than a national issue for debate; in fact, just three states—California, Texas, and New York—were home to more than one-half the U.S. Hispanic population. Immigrant-receiving gateway communities have developed elaborate support networks—a set of local accommodations and understandings— that provide new immigrants with the institutional resources (e.g., legal aid services) they need to adjust to their new environments and succeed (Waters and Jiménez 2005). Residents in gateway communities—both from minority and majority populations—were accustomed to interacting on an everyday basis with newcomers who may have different languages or unfamiliar customs.

This has all changed with the geographic spread of Hispanics to other parts of the United States. The national debate has heated up as Hispanics in new destinations upset the status quo in many states and localities, while raising the specter of new ethnic antagonisms, potential job displacement of longtime workers (especially with low skills), and new political alliances and cleavages (Crowley and Lichter 2009; Fennelly 2008; Pfeffer and Parra 2009). Yet the spatial redistribution of America’s Hispanics can best be described as one of interregional population diffusion and local population concentration. The spatially uneven redistribution of Hispanic growth in rural areas is easily demonstrated with data from the 2000 and 2010 decennial censuses. In the nonmetro Midwest, for example, just 8 percent of counties accounted for 50 percent of the Hispanic population growth (see Table 2). In the South, just 10 percent accounted for 50 percent of the 2000–2010 Hispanic population increase. The new Hispanic population growth is highly concentrated spatially in rural areas.

Table 2.

Distribution of Nonmetropolitan Hispanic Growth, 2000–2010.

| Region | 2000–2010 Hispanic Growth |

Number of Nonmetro Counties |

Number of Nonmetro Counties Accounting for 50 Percent of Growth |

Percent of Nonmetro Counties Accounting for 50 Percent of Growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1,162,834 | 2,043 | 160 | 7.8 |

| Northeast | 66,196 | 94 | 7 | 7.4 |

| Midwest | 223,701 | 762 | 60 | 7.9 |

| South | 588,277 | 871 | 86 | 9.9 |

| West | 284,660 | 316 | 26 | 8.2 |

Many of the least racially diverse nonmetropolitan counties and rural towns in America are located in the Midwest (Johnson and Lichter 2010; Lee et al. 2011). In South Dakota, for example, are three of the least diverse micropolitan places in the nation: Watertown (3), Mitchell (13), and Aberdeen (23) (Lee et al. 2011). Only 2.7 percent of the population of Watertown self-identified themselves as Hispanic in the 2010 census. Hispanic growth and diversity instead have occurred in places where employment is linked to a few clearly defined industries (Broadway 2007; Kandel and Parrado 2005; Parrado and Kandel 2008). For example, some communities in the Midwest and Southeast with meat processing or meatpacking plants represent geographic “hot spots” for Hispanic growth (Gouveia, Carranza, and Cogua 2005; Griffith 2005). Hispanics are willing to do the “dirty work” that native workers apparently eschew. Hispanic growth is linked directly to rural industrial restructuring (especially in nondurable manufacturing, which includes food processing) and, more generally, to a rapidly globalizing agro-food system.

Rural America’s new immigrant destinations—which can only be identified because they represent exceptional rather than spatially diffused Hispanic growth—have spurred a burgeoning literature on issues of immigrant assimilation and native accommodation (for reviews, see Massey 2008a; Zúñiga and Hernández-León 2005). Hispanic population growth has been truly extraordinary in some small communities. As one example, Worthington, Minnesota, is typical rather than the exception. Its Hispanic population increased from 392 in 1990 to 4,521 in 2010, based on the 2010 decennial census. Hispanics now make up 35 percent of Worthington’s population (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). In 1990, Hispanics accounted for only about 4 percent of the population (U.S. Census Bureau 1993). Worthington is home to JBS USA (formerly Swift & Company, one of the world’s largest beef and pork processors).

Majority-Minority Nonmetropolitan Communities

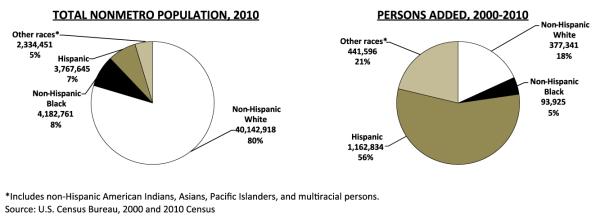

Another indicator of spatially uneven rural minority population growth is the rise in so-called majority-minority communities—places with populations that contain more ethnoracial minorities than non-Hispanic whites. New results from the U.S. decennial census show remarkable increases—more than a doubling—in the number of majority-minority rural communities, from 757 in 1990 to 1,760 in 2010 (see Table 3). In nonmetropolitan areas, the percentage of majority-minority communities increased from 7 to nearly 13 percent of the total. The rate of growth of majority-minority rural communities since 1990 nearly equaled the growth in the number of majority-minority central cities and suburban communities.

Table 3.

Majority-Minority Communities, 1990–2010.

| 1990 |

2000 |

2010 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Principal city | 89 | 13.5 | 155 | 23.3 | 214 | 31.7 |

| Suburb | 733 | 6.9 | 1,282 | 11.1 | 2,061 | 14.7 |

| Nonmetro area | 757 | 7.0 | 1,119 | 9.7 | 1,760 | 12.6 |

| Total | 1,579 | 7.2 | 2,556 | 10.7 | 4,035 | 14.0 |

Note: Computations provided courtesy of Domenico Parisi and the National Strategic Planning and Analysis Research Center, Mississippi State University.

The percentage with majority-minority populations nevertheless remains much higher in central cities (32 percent) than in small towns (13 percent), but the latter is nearly identical to percentages found in suburban places (15 percent). The recent emergence and growth of “ethnoburbs” at the fringe of metropolitan central cities has attracted most of the scholarly attention (Wen, Lauderdale, and Kandula 2009). The emergence of majority-minority rural communities is neither widely known nor often studied.

Until recently, rural majority-minority places were located overwhelmingly in the southern “black belt” (Wimberly and Morris 1997). While rural majority-minority places remain concentrated in the black belt, recent data also indicate that the regional distribution of majorityminorities places has become considerably more dispersed. Figure 2 identifies the census year when nonmetropolitan places reached majority-minority status. Newly emerging majority-minority rural places—those having minority populations of 50 percent or more only after 2000—are concentrated on the West Coast and along the Eastern Seaboard. They also are newly scattered throughout the midwestern states, a pattern that is consistent with the concentration of Hispanics working in small towns with large meat processing plants. They also suggest the emergence of new ethnic enclaves (or, worse, ghettos) in rural America that both accommodate newcomers and reinforce cultural expressions of Hispanicity (e.g., language), which slow the process of incorporation. Unfortunately, we know surprisingly little about the local institutions—businesses, churches, civic organizations, and the like—that serve rural Hispanics.

Figure 2.

Number and Percentage of Majority-Minority Places, 1990–2010. Note: Figure provided courtesy of staff at the National Strategic Planning and Analysis Research Center at Mississippi State University.

Migration and Immigration

During the 1965–1990 period, new immigration flowed largely to these five states: California, New York, Texas, Florida, and Illinois (Massey and Capoferro 2008). Among immigrants who arrived during the five years before the 1990 census, over two-thirds settled in these states. Among Mexican-origin immigrants, the figure was even higher—77 percent. Since then, however, Mexican and other Hispanic populations have spread to virtually every region and state in the nation, including its rural parts. The conventional view is that the rapid but uneven growth of the Hispanic population in rural areas reflects new in-migration of Hispanicsfrom traditional metropolitan gateways and Mexico and other parts of Latin America (Lichter and Johnson 2009).

Aggregate Hispanic migration flows between metro and nonmetro counties, however, are not what they seem; net migration flows favor metro areas at the expense of nonmetro areas. In fact, results from the annual March demographic supplements of the Current Population Survey show that 432,000 Hispanics moved from metro to nonmetro areas between 2000 and 2003, well below the 764,000 Hispanics moving from nonmetro to metro areas (see Table 4).3 The period marking the “Great Recession” (2007–10) clearly has dampened Hispanic migration flows, although the basic pattern of net domestic nonmetro out-migration of Hispanics persists. The implication is clear: the growth of urbanorigin Hispanic in-migrants in nonmetropolitan areas is highly concentrated in a comparatively small percentage of counties. The other implication—less well appreciated—is that Hispanics in other parts of rural America must, by definition, be increasingly moving to metropolitan areas. Some rural areas are becoming increasingly Hispanic in ethnoracial composition, while others are apparently moving in the opposite direction racially.4 Concentrated settlement patterns in rural America suggest a new kind of ethnoracial balkanization or spatial fragmentation.

Table 4.

Nonmetro Migration Patterns among Hispanics, 2000–2003 and 2007–10 (Numbers in 1000s).

| 2000–2003 | 2007–10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic net migration | −332 | −106 |

| Nonmetro-to-metro | 764 | 337 |

| Metro-to-nonmetro | 432 | 231 |

| In-migration from abroad | 139 | 65 |

| Net migration | −193 | −41 |

Source: Current Population Survey, U.S. Census Bureau.

Massey and Capoferro (2008) show that only 10 percent of recently arrived immigrants from Mexico settled in new destinations (defined at the state level) between 1985 and 1990. A decade later, during the1995– 2000 period, however, this percentage increased substantially, rising to 30 percent of the Mexican population. Hispanic immigrants also are increasingly moving directly into nonmetropolitan areas, having bypassed traditional metropolitan gateways that in the past have served as staging areas for subsequent out-migration (i.e., secondary migration to rural areas). The exchange of Hispanic domestic migrants resulted in a net migration loss of nearly 332,000 Hispanics in nonmetropolitan America during the early 2000s (Table 4). But, significantly, this rural loss from Hispanic nonmetro-to-metro out-migration was partly offset by the addition of roughly 139,000 Hispanic immigrants from abroad during this period. This means that some rural communities are attracting newcomers with little previous exposure to American society and fewer interpersonal and community resources to easily adapt to their new environment. They are disproportionately poor, noncitizens, and unauthorized.

In the aforementioned case of Worthington, Minnesota, over one-half of the Hispanic population in 2000 census was foreign-born. Language difficulties represent an obvious barrier to economic incorporation and upward mobility. In Worthington, 78 percent of the Hispanic population spoke a language other than English at home (and this figure does not include the population under age five in the numerator). New immigrants from Mexico and Latin America may face other hardships, including discrimination and exploitation in the workforce. This may be especially true if they are here illegally and lacking legal recourse or a welfare safety net.

Ethnoracial Diversity from the Bottom Up

In previous work with Kenneth Johnson (Johnson and Lichter 2008, 2010), we showed that fertility has played a large and unappreciated role in the rapid growth of the U.S. Hispanic population. The United States is moving inexorably toward a majority-minority society. But for children and youth, the future is now. Hispanic natural increase accounted for over one-half (53.4 percent) of all nonmetropolitan population growth between 2000 and 2005 (Johnson and Lichter 2008). Most work on “new destinations” has focused on Hispanic in-migration (of both natives and the foreign-born). But as we have observed, rural communities in the aggregate are losing Hispanic residents to metropolitan areas. In-migration is spatially uneven, and so is Hispanic fertility.

Fertility clearly represents a large but often unappreciated demographic component of Hispanic growth in rural areas. Hispanic natural increase reflects both high fertility rates (Johnson and Lichter 2010) and the effects of low death rates by virtue of its comparatively youthful age structure (i.e., a low percentage of Hispanics in older, high-mortality,age groups). At the same time, white out-migration has resulted in absolute declines in the population of women of reproductive age (Johnson and Lichter 2010). Current Hispanic fertility rates exceed the national average; for example, Hispanic total fertility is roughly one child higher than the rate for whites (2.9 versus 1.8) (for review, see Parrado 2011). Diversity is increasing from the bottom up in Hispanic boom towns. Clearly, the prospect for rapid ethnoracial change over the next decade or two is extraordinary.

Analyses show that high fertility among Hispanics has been driven in part by the Mexican-origin population and the new immigrant population (e.g., noncitizens, those with poor English language skills). But high fertility rates among Hispanics—and Mexican-origin Hispanics in particular—cannot be explained entirely by sociodemographic characteristics that place them at higher likelihood of fertility. For 2005–8, Hispanic fertility rates were roughly 30 percent higher than fertility among whites, even after controlling for Hispanic–non-Hispanic white differences in social characteristics (Lichter et al. forthcoming). And contrary to most previous findings on spatial assimilation, fertility rates among Hispanics in new destinations exceeded fertility in established gateways. This seemingly reinforces the view that Hispanic boom towns represent new ethnic enclaves that exhibit traditional cultural patterns and, perhaps, dissimilation rather than assimilation or incorporation into the white majority population (Jiménez 2009).

In Nobles County, Minnesota—home of Worthington—there were 286 births between April 1, 2000, and March 31, 2001. Hispanics accounted for only 70 of them. By 2007, however, Hispanic births exceeded non-Hispanic births—165 to 154.5

Uneven Immigration Impacts

Hispanic and other minority growth has dispersed nationally but also is highly concentrated locally. This means that the impact—positive and negative—of Hispanic growth is also highly uneven. The theory of cumulative causation suggests that specific origin-to-destination migration streams have built-in momentum (via migration networks) that can occur quite independently from the growth of job opportunities (Fussell and Massey 2004; Light and von Scheven 2008). The uneven rural growth of Hispanics may accelerate over time, even as local economic conditions change (Marrow 2011).

The emergence of rural ethnic enclaves implies uneven impacts, both on in-migrants and destination communities. As Waters and Jiménez (2005:107) state the case:

The shift in settlement patterns among immigrants to new destinations and the continuing replenishment of new immigrants through ongoing migration streams mean that the emerging literature on immigration will have to take a new empirical and theoretical focus. Empirically, it is time to move away from city-based studies in traditional gateways and look at the transformation of the South, the Midwest, and small cities, towns and rural areas, and suburban areas as sites of first settlement.

Waters and Jiménez (121) further assert that the “United States continues to show remarkable progress in absorbing new immigrants.” Indeed, recent summaries of the history of American immigrant incorporation generally tell a positive story (Bean and Stevens 2003). But is this true now in rural areas?

Here, I revisit conventional theoretical notions about the putative link between social and geographic mobility, interrelated patterns of white and Hispanic migration (e.g., white flight), and politics and generational conflict. How has rural America been transformed by new Hispanic in-migration? What do rural enclaves suggest about the spatial patterning of assimilation, community impacts, and shifting ethnoracial boundaries?

Migration and Upward Mobility

The so-called spatial assimilation model suggests that immigrants become integrated residentially with natives as they become economically assimilated.6 Economic incorporation expands housing and neighborhood options, while in turn promoting additional opportunities for upward mobility. In the Hispanic case, however, the work available in rural labor markets typically comprises low-wage, low-skill jobs. The urban enclave economy has moved to the hinterland. These jobs have attracted recent Hispanic immigrants who are the least educated, have the most language and cultural barriers, and are most likely to be unauthorized among immigrants (Donato et al. 2007; Farmer and Moon 2009; Kochhar, Suro, and Tafoya 2005). The work is often hard, dirty, and dangerous—jobs in agriculture, meatpacking plants, and construction—which white native-born workers find unattractive (Gouveia et al. 2005; Stull and Broadway 1995). The new rural in-migration of Hispanics also has followed the growth of low-wage jobs in oil, timber, furniture, carpeting, textiles, and other nondurable manufacturing (Hernández-León and Zúñiga 2000; Murphy, Blanchard, and Hill 2001). As a context for immigrant reception, rural labor markets seemingly provide few opportunities for upward intragenerational or intergenerational mobility.

Unfortunately, despite a growing literature on new immigrant destinations, there have been surprisingly few comparative community studies of Hispanic immigrant incorporation in new rural destinations (Kandel et al. 2011; Kritz, Gurak, and Lee 2011). In work with Martha Crowley and Zhenchao Qian, we used data from the 2000 Integrated Public Use Microdata Samples to compare native-born and foreign-born Mexicans living in the Southwest and elsewhere (Crowley, Lichter, and Qian 2006). We found that Mexican workers, especially immigrants, living outside Southwest gateway communities had significantly lower rates of poverty than those who remained in the Southwest. More recently, Kandel et al. (2011) compared Hispanic immigrants in “traditional” immigrant gateways with those in “new” rural immigrant destinations. They also found that Hispanic poverty rates were lower in new rural destinations (24 percent) than in rural gateways (27 percent) but higher than in metropolitan areas (18 percent) in 2006–7.7 Neither Crowley et al. (2006) nor Kandel et al. (2011) actually tracked individual or family changes in poverty before and after moving from gateways to new destinations. Establishing a statistical link between new immigrant boom towns and economic incorporation among Hispanic in-migrants represents an important but seriously understudied topic.

For children of rural Hispanic immigrants, we know even less about their educational achievement, opportunities for upward mobility, and patterns of out-migration in early adulthood. Children of immigrants, even if they are citizens by birth, face obvious challenges by virtue of having parents who may not speak English well, who are poor, and who are often less educated themselves. Young children who enter the country illegally (usually with their parents) face even more difficult circumstances and few obvious pathways to social, political, or economic incorporation. The Dream Act, which currently is being debated in the U.S. Congress, is designed to pave the way to citizenship for undocumented children who came to America illegally but who have “played by the rules” (i.e., stayed out of trouble, graduated from high school or college, or served in the military). In many rural areas, local school districts face a burgeoning Hispanic school-age population that they are unable to accommodate with culturally appropriate instructional or support services (e.g., instruction in English as a second language [ESL]). Not surprisingly, Hispanics face unusually high dropout rates that greatly limit socioeconomic mobility and full participation in American society. The second generation is the linchpin in the assimilation process (Kasinitz et al. 2008; Portes 1996). Now is a propitious time to study the new second generation in rural America and its progress in school, relationships with teachers and peers, and links to other institutions (e.g., social services providers and police).

The disadvantaged circumstances of new immigrants are easily documented in Worthington, Minnesota, where the poverty rate among Hispanics in 2005–9 was 52.9 percent (s.e. = +/−10.7), compared with 27.9 percent (+/−4.9) for Worthington overall and 12.9 percent (+/−3.5) for Worthington’s white population. According to the 2005–9 American Community Survey, the poverty rate nationally among Hispanics is 21.9 percent. Among Hispanics, poverty is 2.4 times higher in Worthington than in the nation. Among Worthington’s white population, poverty rates are only 1.4 times higher than among the nation’s white population.

Social Disorganization and White Flight

Most studies of new destinations have focused much less on the economic plight and social mobility of Hispanic newcomers than on the negative consequences for the community. These community-based studies often focus on poverty and welfare dependence, overcrowded schools, interethnic conflict, and crime, among other negative consequences of rapid Hispanic growth (Crowley and Lichter 2009). Of course, these concerns reflect the putative social disorganization of community life (predicted by the Chicago School of sociology), change brought on by rapid growth of culturally different and poor populations. In the end, however, most systematic quantitative studies indicate few large negative effects on local communities overall and, in some cases, Hispanic in-migration has been an economic godsend that has revitalized local economies (for discussion, see Carr, Lichter, and Kefalas forthcoming; Jensen 2006).

For example, crime is often thought to be associated with Hispanic population increases and the recent influx of immigrants from Mexico and Latin America. The current governor of Arizona has used high crime rates (e.g., from drug cartels along the border) as a rallying cry to gain popular support for tough new anti-immigrant legislation (O’Leary and Romero 2011). Comparative studies—both in rural and urban areas—show that crime rates are in fact lower overall in new destinations than in otherwise similar communities. Crowley and Lichter (2009), for example, a study that controls for unobserved heterogeneity, found that arrest rates for violent crimes were identical in established Hispanic gateways and Hispanic boom towns. Violent crime rates (as reported to the police) declined in new destinations during the 1990s, albeit somewhat less rapidly than in traditional gateways. The empirical evidence for the disorganization thesis in new Hispanic boom towns overall is not compelling.

What is less clear is what happens to communities when job growth ends (e.g., a meat processing plant closes). A recent study (Broadway and Stull 2006) in Garden City, Kansas, suggests that community decline rather than community growth may drive future scholarly interest in social disorganization in today’s Hispanic boom towns.

Most accounts suggest that Hispanic in-migration and population growth have rejuvenated many small towns, especially in the depopulating parts of the rural Midwest (Carr et al. forthcoming). Indeed, in the early 2000s, a total of 221 nonmetropolitan counties would have experienced absolute population decline in the absence of Hispanic growth (Johnson and Lichter 2008). Urban minority transplants now are replacing younger white out-migrants and rapidly aging and dying older people. An obvious question, of course, is whether the new in-migration of Hispanics has replaced or displaced native-born whites. The conventional view—at least so far—is that Hispanics have moved into declining small towns (i.e., replacement). However, a recent study by Crowder, Hall, and Tolnay (2011) now suggests that out-migration of native-born whites and blacks is positively associated with the relative size and growth of the immigrant population. These analyses are based on metropolitan panel data from the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics, linked to neighborhood data from the 1970, 1980, and 1990 censuses.

The emptying of small town America, however, seems much less closely linked to Hispanic in-migration. Many small communities, especially in the Midwest, have lost white population to out-migration for decades (Johnson and Fuguitt 2000). For example, since 1910, Worthington, Minnesota, had not experienced population losses in any decade until the 1980s, when it declined in population size by 2.6percent. In this case, population decline preceded the subsequent rapid in-migration of Hispanics in the 1990s and 2000s, a fact that suggests a process of population replacement rather than displacement (or white flight) in Worthington. Of course, establishing linkages between Hispanic in-migration and white out-migration represents a potentially important demographic dimension of the emergence and rapid growth of Hispanic enclaves in rural America. It also suggests the replacement of a rural-based indigenous population (born and raised) with an urbanbased transient and minority population.

Aging-in-Place and Hispanic Population Growth

Johnson (2011) has recently documented large increases in the number of rural counties that are now experiencing natural decrease—the excess of deaths over births. The number of natural decrease counties (all nonmetro) increased from 483 in 1990 to a record 985 in 2002. Almost one-half of all counties experienced at least one year of natural decrease since 1990. Natural decrease counties are located overwhelmingly in the heartland, from North Dakota to the panhandle of Texas. These counties have experienced out-migration of young adults for decades, along with rapidly declining fertility (largely because of absolute declines in the number of women of reproductive age). Population aging has accelerated rapidly while giving demographic impetus to higher death rates that often exceed birth rates. Natural decrease has been inevitable from a strictly demographic standpoint.8

The new historical coincidence of widespread natural decrease and Hispanic in-migration raises interesting theoretical and substantive issues about intergenerational relationships and local politics in America’s small towns.9 Indeed, the political and economic interests of an aging, white, and longtime resident population seem to be pitted against those of younger Hispanic families and their children, who may have less long-term attachment to place. Rural communities have always had great potential for substantial intergenerational conflict, a situation that may now be exacerbated by changing racial and ethnic composition. Previous work in metropolitan communities, for example, has shown that older whites are less likely to vote for a school bond referendum to raise property taxes if the school-aged population is disproportionately composed of minorities rather than white children (Poterba 1997).

Rural Hispanic boom towns provide a natural setting for studying racial politics as we move toward a majority-minority society. In California, where minorities already exceed the number of whites, Dowell Myers (2007) has argued for a new “social contract” across generations, where ethnoracial differences give way to mutual dependency. His aspirational thesis emphasizes the shared destinies of America’s elderly population and new Hispanic immigrants and their children, who represent a new generation of future workers, taxpayers, and homeowners (and buyers) who serve and support the largely white elderly retired population. For the elderly, it presumably is in their political interest to reciprocate, with their votes, by supporting public education and strengthening the welfare safety net (e.g., childhood nutrition programs, ESL programs). Hispanic upward mobility is directly connected to elderly well-being.

Natural decrease may be slowed by Hispanic in-migration, but elderly retirement migration can also be a major source of growth and aging in some high-amenity rural areas. The elderly have been referred to as the “silver tsunami” or “gray gold” (Brown and Glasgow 2008; Nelson, Lee, and Nelson 2009); they spend pension and Social Security monies, an important source of economic development and job creation. Retirement-related population growth also apparently is an impetus for in-migration of immigrants who provide labor in the service, hospitality, and health sectors (Nelson et al. 2009). White elderly and young Hispanic workers are entering into a new synergetic relationship that is driving economic development and community change.

The potential for a new generational divide in some rural communities clearly can be seen in Worthington. Its elderly population, aged 65 and older, was 97 percent white in the 2000 census. In contrast, the Hispanic share of children (under age 18) was 29 percent. Worthington’s Hispanic population of preschool children under age 5 was even higher—38 percent. The 2010 census revealed that only 48.9 percent of Worthington’s total population are now non-Hispanic white.

Footloose or Putting Down Roots?

John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath in 1939 depicted the plight of California farmworkers who sought relief from the 1930s “dust bowl” and the dislocations caused by the mechanization of agricultural production in Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, and other agricultural states in the heart-land. Since the 1940s, however, America has imported mostly Mexican farmworkers (e.g., via the Bracero Program early on) to pick fruits and vegetables in the hot sun of the San Joaquin Valley in California, along the Rio Grande basin in Texas, and in other places. Many migratory farmworkers followed the harvest in the Midwest or other parts of the country (e.g., picking apples in New York State) or worked in allied food processing (e.g., corn and green bean canning operations in Le Suer, Minnesota, or similar places). For rural communities, exposure to a transient Hispanic population was sporadic, and the impact on community resources and tax dollars less clearly defined.

The plight of Hispanic farmworkers has improved, especially since Cesar Chavez organized the United Farm Workers in 1972. There have been improvements in child labor, housing, working hours, and exposure to hazardous conditions (e.g., farm machinery or herbicides and pesticides). New methods of farming also now permit year-round production, which has had the effect of slowing the growth of migratory workers as they settle permanently in traditional agricultural areas, as well as in other agricultural areas up and down the Eastern and Western Seaboards (Kandel 2008). Interestingly, the geographic distribution of hired farmworkers, who account for one-third of America’s agricultural labor force, has changed little over the past decade. California, Florida, Texas, Washington, Oregon, and North Carolina still account for half of all hired and contracted farm workers (Kandel 2008). The major impact from Hispanic population growth in new destinations has not come from agricultural workers, but from workers in other low-wage industrial sectors. In some parts of the country, agricultural workers “settle out” into other jobs as they gain a foothold in the local economy (Marrow 2011).

The changing mix of farmwork and employment in other rural employment sectors (e.g., nondurable manufacturing and services) suggests a considerably more stable Hispanic population, one that has put down “roots” in the community. This is perhaps reflected best in family patterns. One recent study showed that new Mexican-origin in-migrants to rural areas are more likely now to be accompanied by a spouse (Farmer and Moon 2009). The 2009 American Community Survey also shows that 53 percent of nonmetro Hispanics living outside the Southwest (defined as California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas) owned their own homes, compared with 65.5 percent in the Southwest (my calculations). The militarization of the border and the crackdown on unauthorized workers also has changed the nature of transnational communities and the regular flow back and forth between their new home in the United States and their formerhome in Mexico or other parts of Latin America. Stated simply, it is hard to return to the United States after leaving. Hispanics clearly have a new long-term stake in their communities.

The problem is that most rural Hispanics are not U.S. citizens (Massey 2008b). Many are undocumented (Farmer and Moon 2011). They cannot vote or actively participate in civic life; they are part of a new underworld of rural community life that is invisible to longtime community residents. Immigrants do their shopping in Walmart late at night or in the early morning hours so as not to draw the attention of other shoppers. Thus, the kinds of attachments that anchor people to place are easily unhinged. The migrant rural farmworker arguably has given way to the migrant industrial or service worker. Nonmetropolitan Hispanics have exceptionally high rates of geographic mobility. During 2009, for example, 4 percent of nonmetro Hispanics had moved to their current location from outside the state over the past year.10 This compares with 2.3 percent among rural non-Hispanic whites. Of course, some of this difference reflects age disparities between Hispanics and other residents. But even among young adults (25–39), rural Hispanics (5.7 percent) have considerably higher geographic mobility rates than non-Hispanic whites (3.4 percent).

There have been few empirical analyses of secondary migration of rural immigrant populations. A recent study by Kritz et al. (2011), however, tracked the subsequent migration patterns of the foreign-born populations (of all nationalities) in new immigrant destinations. They found that immigrants in new destinations in 1995 were 2.5 times more likely than their counterparts in traditional settlement areas to move to another labor market area by 2000. Over 20 percent left new destinations over this five-year period. Although employment growth and wage rates were negatively associated with out-migration from local labor markets, they did not account for the higher out-migration rates from new destinations. High out-migration rates are intrinsic to new destinations, independent of local economic conditions.11 Moreover, Mexican-origin immigrants in new destinations were nearly twice as likely to out-migrate as those living in traditional gateways, but this migration differential disappeared when other local (e.g., group size) and individual (e.g., citizenship, years in the United States) characteristics were controlled. Other Hispanic-origin populations (e.g., from El Salvador, Dominican Republic, and Guatemala) displayed similar patterns.

Putting down roots is a prerequisite for creating the “good community.” In the urban neighborhood literature (Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls 1997), a transient community is usually regarded as one that is low in collective efficacy, which undermines social ties, informal social control, and the ability to solve local problems. Community attachment also is low, if measured by involvement in fraternal clubs or service organizations. And crime and delinquency rates are sometimes higher (although this depends on whether the community overall is growing or declining). Transient communities do not effectively self-police.

The 2009 strategic plan of Worthington listed various impediments to achieving its “vision and success.” Included in this list of impediments is—using the plan’s words—the “integration ‘elephant,’ ” which blocks a “sense of community” (Fursman and Fursman 2009).

Ethnoracial Boundaries and Race Relations

In the final analysis, changing race relations lie at the heart of the assimilation process and economic incorporation in rural America (Hernández-León and Zúñiga 2005; Hirschman and Massey 2008; Marrow 2009). The current vitriolic national dialogue about immigration—and about race more generally (especially with the election of the first African American president)—has raised obvious questions about changing group boundaries, community solidarity, and America’s future. Are we fragmenting as a society?12

If the past is prologue, the social and cultural boundaries that separate different ethnoracial groups in America, including rural America, are expected to subside with time or with generational replacement. Most national polls suggest long-term declines in racial prejudice and reductions in overt discrimination (in housing or the workplace) on the basis of race or ethnicity. Interracial friendship networks (especially among the young) have grown, as have U.S. interracial marriage rates (Qian and Lichter 2011). Hispanics have among the highest rates of intermarriage with non-Hispanic whites. Moreover, as an indicator of group boundaries, rates of racial residential segregation in the nation’s largest metropolitan cities also have declined over the last 50 years or more (Iceland 2009). And Hispanics have segregation rates from whites that are much lower than those of blacks. With incorporation, residential segregation also has declined between first-generation Hispanics and later generations (Iceland and Nelson 2008).

Other observers are less sanguine, suggesting that America is dividing into “two peoples, two cultures, and two languages,” that assimilation is increasingly segmented, or that Hispanics (unlike white ethnic groups from an earlier period) are hard to assimilate (Huntington 2004:30). Whether national or historical patterns that commonly define group boundaries are played out in rural communities, including new rural immigration destinations, is unclear. In rural areas, growing ethnoracial diversity, if measured by changing racial and ethnic composition or the new influx of Hispanics, does not mean that we have moved to a postracial society if everyday or routine interactions between majority and minority populations are hostile or, maybe worse, limited or nonexistent (Johnson and Lichter 2010).

In her study of Devereux, Minnesota, Fennelly (2008:172) notes that “language barriers and socioeconomic class differences relegate many immigrants to a permanent category of outsiders,” even if they had lived in the community for many years. Interactions between immigrants and U.S.-born whites are instead relegated to formal role relationships, such as teacher-student or manager-worker. New immigrants represented a “symbolic threat” to cultural or national identity, as well as to traditional or nostalgic ways of rural life (152). As outsiders, immigrants often are viewed as eroding the “sense of community” and shared values (that come from similar cultural experiences and backgrounds), something that is usually associated with big city living (Crowley and Lichter 2009). A recent study found that anti-immigrant sentiment in two meatpacking communities in Iowa (Perry and Storm Lake) was strongest among adolescents from affluent families that were deeply rooted in the community (Gimpel and Lay 2008). The greater contact between workingclass teenagers and immigrants in their neighborhoods and schools helped to reduce ethnic tensions.

Hostile attitudes toward new immigrants are also linked to economic threats or to public concerns about welfare dependence or new taxes (e.g., to build schools or hire more teachers) (Massey 2008a). Too often politicians play on people’s fears, especially during economic downturns. In fact, the past few years have brought a rash of new local anti-immigrant ordinances designed to discourage unauthorized workers from settling in the community. Anti-immigrant ordinances come in many forms. Some may impose additional regulations on dayworker agencies, penalize employers who hire unauthorized immigrants, or require that all municipal business be conducted in English only. Other local ordinances restrict landlords from knowingly (or even unknowingly) renting to unauthorized immigrants, which can lead to racial profiling and housing discrimination on the basis of race or ethnicity (Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund 2011). For a recent review of local anti-immigration ordinances and other legal aspects of the new rural immigration, see O’Neil (2010) and Pruitt (2009).

In urban sociology, empirical clues about persistent racial boundaries are often measured indirectly by changing racial residence patterns (Parisi et al. 2011a). Segregation in big cities literally means social isolation from the mainstream: minority neighborhoods are cordoned off from white neighborhoods. Minorities have their own schools, shopping centers, parks, and recreational areas. In small towns, including new immigrant destinations, the opportunities for up-close social interactions presumably are much greater. Hispanics attend the same public schools, patronize the same local merchants, and enjoy the same municipal swimming pools or public parks. Close contact in rural communities creates new opportunities for mutual understanding, as well as for conflict and hostility.

Recent work with Domenico Parisi (i.e., Lichter et al. 2010; Parisi et al. 2011a) suggests that residential segregation in small towns—and new Hispanic destinations in particular—is high between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites. In 2000, overall Hispanic-white segregation, regardless of community size or metropolitan status, was higher in new destinations (58.6) than in established Hispanic places (53.8).13 More importantly, the largest difference between new destinations and traditional settlements (about 12 points on the segregation index) was in nonmetro places rather than in central cities or suburbs. Average segregation rates also were higher in new nonmetro (63.0) and central city destinations (65.2) than they were in new suburban places (50.7).

Clearly, residing in the same communities as non-Hispanic whites does not mean that rural Hispanics share the same neighborhoods. In the case of Worthington, the segregation index was 54.9 in 2000. The social distance between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites in new destinations, including Worthington, is large if measured by residential segregation patterns (Parisi, Lichter, and Taquino 2011b). Segregation is not simply an urban issue or restricted to blacks and whites in rural areas of the South.

In light of current demographic trends, changing rural ethnoracial boundaries and race relations continues to be an understudied topic, especially those in new Hispanic destinations. The ongoing experiences of Hispanic children and young adults will be especially telling. Have Hispanic and white children formed friendships? Will they enter intimate relationships during adolescence? And will propinquity inherent to living in small towns, perhaps unlike big cities, provide greater opportunities for social interaction, intimacy, and marriage? Marital assimilation is in fact often viewed as the final step in the assimilation process (Gordon 1964), one that indicates that persons of majority and minority status are interacting in the marriage market as equals (i.e., in socioeconomic status and education). Of course, informal social control (i.e., stigma and ostracism) in small towns can be a very powerful mechanism that discourages interracial fraternization, unlike the anonymity and greater tolerance found in most large cities.

Looking Forward

The recent immigrant influx and rapid change in the ethnoracial composition of rural America is central to virtually every aspect of the rural sociological enterprise and rural social science. The new growth of rural immigrant minorities, in particular, is linked in fundamental ways to a much larger set of theoretical and substantive issues: the globalization of labor; structure of agriculture; agro-food systems; loss of community; economic development and cultural change; environment and “green jobs”; growth and decline in the rural labor force; demographic change (including fertility); educational attainment and the structure of rural schools; rural children’s healthy development; crime and deviance; racial stratification and rural poverty; and racial relations, among other topics. Racial and ethnic diversity is at the leading edge of major changes in rural community life—and the nation. These are issues that clearly link the urban economy with rural America, and have contributed to the new blurring of rural-urban boundaries (Lichter and Brown 2011; Woods 2009).

In New Faces in New Places, Massey (2008b) suggests that the route to Americanization among Hispanics everywhere may be more difficult than the path traveled a century ago by white ethnic groups from Europe. He lists five primary reasons. First, the opportunities for upward mobility may be more limited with economic globalization, stagnation inwages (especially at the bottom of the earnings distribution among the least educated), and growing income inequality. Second, a good education is more important than ever in America’s new and rapidly restructuring economy, but access to good schools and educational attainment (even by the third generation) remains low among Hispanics. Third, the continuing influx of first-generation immigrants from Mexico and elsewhere has often reinforced cultural and linguistic isolation in the Hispanic immigrant community, while dampening real prospects for intragenerational and intergenerational upward mobility. Fourth, large and unprecedented shares of Hispanic immigrants are undocumented, joining a permanent underclass that may prevent their children from moving ahead in American society. Fifth, Hispanics today face a “remarkable revival of immigrant baiting and ethnic demonization” by “demagogues in politics, the media, and even academia” (346).

These barriers to integration and incorporation would seem to be especially high for rural Hispanics. For example, rural America has perhaps been most affected over the past 40 or 50 years by industrial and economic restructuring (Brown and Schafft 2011). The rural economy has faced unprecedented competition from cheap labor globally, and opportunities for upward mobility and economic incorporation seem limited. Rural schools may be especially ill equipped to promote integration if they lack the resources, experienced teachers, or a cultural sensitivity to new immigrant populations of children that are exposed to a voting older population that often views them as a problem rather than a resource for the future. Unlike in big cities, the geographic isolation of rural Hispanics, along with a continuing stream of new in-migrants, also has the potential to reinforce cultural isolation and block upward mobility. Undocumented workers are overrepresented in the rural labor force, a fact that makes economic, political, and cultural incorporation almost impossible. And, lastly, rural Hispanic immigrants may face extraordinary prejudice or job discrimination (outside the niche occupations) among longtime rural residents who have never before been exposed to minority populations who speak a different language or who do not embrace American culture in their daily lives (e.g., they dress differently, eat different foods, and listen to different music from native whites). Most attitude surveys continue to show substantial rural-urban differences in racial and anti-immigrant prejudice (Fennelly and Federico 2008), although local community and business elites often view immigration positively because it brings business and tax dollars (Hirschman and Massey 2008).

Looking forward 10 or 20 years, it is easy to imagine an acceleration of current demographic changes in today’s Hispanic boom towns, even ifimmigration laws are made more restrictive. Common sense tells us that America’s 12 million undocumented immigrants are unlikely to voluntarily leave the country or, alternatively, to be easily rounded up and returned to their native countries. Interdiction is not the solution (Carr et al. forthcoming). An aging-in-place rural white population (i.e., the large baby-boom generation) will be dying off, leaving behind a population increasingly made up of minority young people whose poor parents often worked at menial and low-paying jobs with little opportunity to move forward economically. Today’s children also will be entering the labor force, getting married, and having children. Will they stay in their communities (reinforcing the ethnic enclave and reproducing the lives of their parents) or will they move elsewhere? This will depend, of course, on the quality of local schools, on the job opportunities available to them locally, and on the reception of the native-born white population. The situation also will depend on whether Hispanic growth today is occurring in the context of white growth or white decline, that is, whether Hispanics represent an ethnic or cultural threat born of local demographic or economic conditions.

Some scholars provide a more optimistic demographic scenario. Richard Alba (2009), in Blurring the Color Line, suggests that the aging and retirement of America’s (mostly white) baby-boom generation will open unprecedented new (good) job opportunities for minorities and immigrants. White retirees from middle-class and professional jobs will be replaced disproportionately by new minorities. Increasing education and job equality presumably will hasten the blurring of the “bright boundaries” that have historically separated the races in the United States. The opportunities for immigrant incorporation associated with generational succession in the rural labor force, however, seem distinctly different from employment opportunities nationally or in large and dynamic big-city labor markets. The new job openings created by rural retirement over the foreseeable future are unlikely to provide sufficient good jobs or ensure upward mobility among Hispanics. And if the recent past is any indication, any new jobs added to the rural labor force are likely to be filled disproportionately by low-skilled workers. The lesson, of course, is that rural children—Hispanic children—will reshape the future of many towns with recent large influxes of Hispanics from Mexico or other parts of Latin America.

The future of today’s rural Hispanic boom towns will also depend on economic conditions in Mexico and Latin America and on the decisions of U.S. urban-based or other multinational corporations. Previous studies show that labor mobility from Mexico and Latin America to the United States is negatively selected. It is the least educated and skilledwho are entering the United States. Changing economic circumstances in origin countries can profoundly affect flows to the United States and their characteristics. Immigrant laws (here and abroad) also matter. In the 1920s, the spigot of immigration from Asia and southern and eastern Europe was cut off by highly restrictive immigration laws. The limited replenishment of immigrant labor—and culture—had profound effects on assimilation and the blurring of boundaries between white ethnic groups from different countries. Generational succession leads inevitably to a breakdown of ethnic identity, along with the declining influences of ethnic neighborhoods, religion, and extended kin (Alba and Nee 2003). Different national origin groups intermarried and had children, which only served to hasten the “whitening” process or Americanization process. If the spigot of immigration from Latin America is turned off—either because of new immigration legislation or because the economic climate changes current incentives to move to the United States—then a similar process of incorporation and boundary blurring may occur among today’s diverse Hispanic population. A U.S. minority population comprising mostly secondand third-generation Hispanics will be much different from a population made up of first-generation immigrants.

Conclusion

In the final analysis, it is difficult to foretell the long-term future of new Hispanic destinations, especially in rural areas. If past is prologue, perhaps there are reasons to be optimistic. A look back to the nineteenth century and early twentieth century reveals considerable anti-immigrant sentiment against Irish and Italian Catholics, the Chinese from Asia, and Jews from Russia and eastern Europe that eventually gave way to greater tolerance and a blurring of the color line (Hirschman and Massey 2008). For Hispanics in contemporary rural America, the current situation is highly fluid; indeed, studies of rural social and economic change in Hispanic boom towns often seem out-of-date by the time they are published. Immigration flows are in flux, as is the secondary migration of immigrants in the United States. The “Great Recession,” slow job and earnings growth, and a depressed construction industry clearly have also disrupted recent patterns of immigration and internal secondary migration. Flows to and from Mexico have shifted and many workers seem frozen in place by depressed economic conditions (everywhere) and by the bust in the housing market (Rendall, Brownell, and Kups 2011).

One thing is clear, however. The uneven growth of the Hispanic population in rural America—the development of rural Hispanicenclaves—provides unusually rich opportunities for better understanding the causes and consequences of rural racial and ethnic change, racial relations, segmented cultural and economic assimilation, and the spatial patterning of social, economic, and cultural incorporation among a historically disadvantaged population that will reshape America’s future (Tienda and Mitchell 2006). It is time to work on these issues.

Footnotes

During the 2008 Obama-McCain presidential campaign, on stops in hardscrabble parts of rural Pennsylvania, Appalachia, and elsewhere, vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin sometimes referred to her audience as “real Americans.” Some observers interpreted this reference as code words for “white” that distinguished the McCain campaign from Barack Obama’s. The 423 counties that make up the Appalachia region are nearly 90 percent non-Hispanic white (Pollard 2004).

The entropy index gauges how evenly members of a population are spread across ethnoracial categories (Lee et al. 2011). Values range from 0, which indicates racial homogeneity, to 100, which means that all racial groups are represented in equal percentages in the county.

These dates refer to the survey dates. The 2000 Current Population Survey, for example, identifies migrants during the 12 months preceding the interview.

Results from the 2010 census, for example, indicate declining racial minority percentages in traditional rural minority settlement areas—Indian reservations, the southern black belt, and the lower Rio Grande valley (Humes et al. 2011). This pattern reflects minority out-migration rather than white in-migration.

This information is kindly provided courtesy of Kenneth Johnson and is based on information from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Indeed, there is a large literature in urban sociology devoted to the question of whether new immigrants benefit or not from leaving urban ethnic enclaves (see Portes and Jensen 1989). The ethnic economy presumably provides employment opportunities for upward mobility where none exist elsewhere (where new immigrants face language barriers or discrimination).

Perhaps surprisingly, these authors found that Hispanic immigrants in new rural destinations had much higher rates of homeownership than Hispanics living elsewhere. They suggest that this may indicate a more mature or settled Hispanic population in new destinations. Alternatively, this may simply reflect the low cost of housing in rural areas in general and in some declining new destinations in particular.

In South Dakota, for example, 14.5 percent of its population was 65 or older in 2010, a figure above the national average (12.9 percent) but lower than in Florida (17.2 percent). But whereas Florida’s aging population reflects in-migration of retirees, population aging in South Dakota and other rural areas of the Midwest reflects persistent out-migration of the young and the second-order effect of low fertility and high mortality.

Johnson (2011) reported that 570 counties experienced natural increase between 2000 and 2005, but only because natural decrease among non-Hispanic whites was more than offset by natural increase (mostly because of high fertility) among minority populations.

These estimates are based on analyses of the 2009 American Community Survey for individuals aged one or older at the time of the survey.

These results may reflect that fact that immigrants living in new destinations are less rooted or attached to the community (e.g., friendship or kin networks). They possess other unobserved characteristics (e.g., risk takers) that elevate the likelihood of repeat migration. These variables were not considered by Kritz et al. (2011).

As Fischer and Mattson (2009:443) state the case: “The strongest framing of lifestyle fragmentation is the claim that the great majority of Americans once shared a common set of worldviews and ways of life and that this unity splintered since 1970 so that by 2000 Americans divided into numerous, increasingly distinct and estranged social worlds.” As a general point, these authors argue that there is little evidence of increasing fragmentation by ethnoracial background or even nativity, but also indicate caveats (e.g., unauthorized immigrants) that may suggest a short-term pause in the process of Americanization.

Segregation is measured here with the index of dissimilarity. Its values range from 0 to 100. A value of 58.3 means that 58.3 percent of Hispanics would have to move to other blocks in the community before Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites are distributed in the same percentage across all blocks in the community.

This article is a revised version of the presidential address presented at the annual meetings of the Rural Sociological Society, Boise, ID, on July 28, 2011. I acknowledge the computing assistance of Lisa Cimbaluk and Richard Turner as well as the helpful comments of David Brown, Charlie Hirschman, Ken Johnson, William Kandel, Mimmo Parisi, and Sharon Sassler on early drafts of this article.

References

- Alba Richard. Blurring the Color Line: The New Chance for a More Integrated America. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Alba Richard, Nee Victor. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D., Stevens Gillian. America’s Newcomers and the Dynamics of Diversity. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Broadway Michael J. Meatpacking and the Transformation of Rural Communities: A Comparison of Brooks, Alberta and Garden City, Kansas. Rural Sociology. 2007;72:560–82. [Google Scholar]

- Broadway Michael J., Stull Donald D. Meat Processing and Garden City, KS: Boom and Bust. Journal of Rural Studies. 2006;22:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Brown David L, Glasgow Nina. Rural Retirement Migration. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brown David L., Schafft Kai A. Rural People and Communities in the 21st Century: Resilience and Transformation. Polity Press; Cambridge, England: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Ralph B., Dorius Shawn F., Krannich Richard S. The Boom-BustRecovery Cycle: Dynamics of Change in Community Satisfaction and Social Integration in Delta, Utah. Rural Sociology. 2005;70:28–49. [Google Scholar]

- Carr Patrick J, Lichter Daniel T., Kefalas Maria J. Can Immigration Save Small-Town America? Hispanic Boomtowns and the Uneasy Path to Renewal. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Castle Emery, Wu JunJie, Weber Bruce A. Place Orientation and Rural-Urban Interdependence. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy. 2011;33:179–204. [Google Scholar]

- Crowder Kyle, Hall Matthew, Tolnay Stewart E. Neighborhood Immigration and Native Out-Migration. American Sociological Review. 2011;76:25–47. doi: 10.1177/0003122410396197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley Martha, Lichter Daniel T. Rural Sociology. 2009;74:573–604. [Google Scholar]

- Crowley Martha, Lichter Daniel T., Zenchao Qian. Beyond Gateway Cities: Economic Restructuring and Poverty among Mexican Immigrant Families and Children. Family Relations. 2006;55:345–60. [Google Scholar]

- Donato Katharine M., Tolbert Charles M., II, Nucci Alfred, Kawano Yukio. Recent Immigrant Settlement in the Nonmetropolitan United States: Evidence from Internal Census Data. Rural Sociology. 2007;72:537–59. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer Frank L., Moon Zola K. An Empirical Examination of Characteristics of Mexican Migrants to Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Areas of the United States. Rural Sociology. 2009;74:220–40. [Google Scholar]

- An Empirical Note on the Social and Geographic Corerlates of Mexican Migration to the Southern United States. Journal of Rural Social Sciences. 2011;26:52–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fennelly Katherine. Prejudice toward Immigrants in the Midwest. Massey. 2008. pp. 151–78. 2008a.

- Fennelly Katherine, Federico Christopher. Rural Residence as a Determinant of Attitudes toward U.S. Immigration Policy. International Migration. 2008;46:151–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer Claude S., Mattson G. Is America Fragmenting? Annual Review of Sociology. 2009;35:435–55. [Google Scholar]

- Frey William H. Melting Pot Cities and Suburbs: Racial and Ethnic Change in Metro America in the 2000s. Brookings Institution: Metropolitan Policy Program; State of Metropolitan America. Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fursman Richard, Fursman Irina. [Retrieved July 13, 2011];City of Worthington Strategic Plan 2009. 2009 http://www.ci.worthington.mn.us/sites/default/files/news_release/2011/06/Strategic%20Plan%20Final%20Adopted%20Report%20 2009%20(2).pdf)

- Fussell Elizabeth. Sources of Mexico’s Migration Stream: Rural, Urban, and Border Migrants to the United States. Social Forces. 2003;82:937–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell Elizabeth, Massey Douglas S. The Limits of Cumulative Causation: International Migration from Mexican Urban Areas. Demography. 2004;41:151–71. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimpel James G., Lay J. Celeste. Political Socialization and Reactions to Immigration-Related Diversity in Rural America. Rural Sociology. 2008;73:180–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon Milton M. Assimilation in American Life. Oxford University Press; New York: 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia Lourdes, Carranza Miguel A., Cogua Jasney. The Great Plains Migration: Mexicanos and Latinos in Nebraska. Zúñiga and Hernández-León; 2005. pp. 23–49. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith David C. Rural Industry and Latino Immigration and Settlement in North Carolina. Zúñiga and Hernández-León; 2005. pp. 50–75. 2005. [Google Scholar]