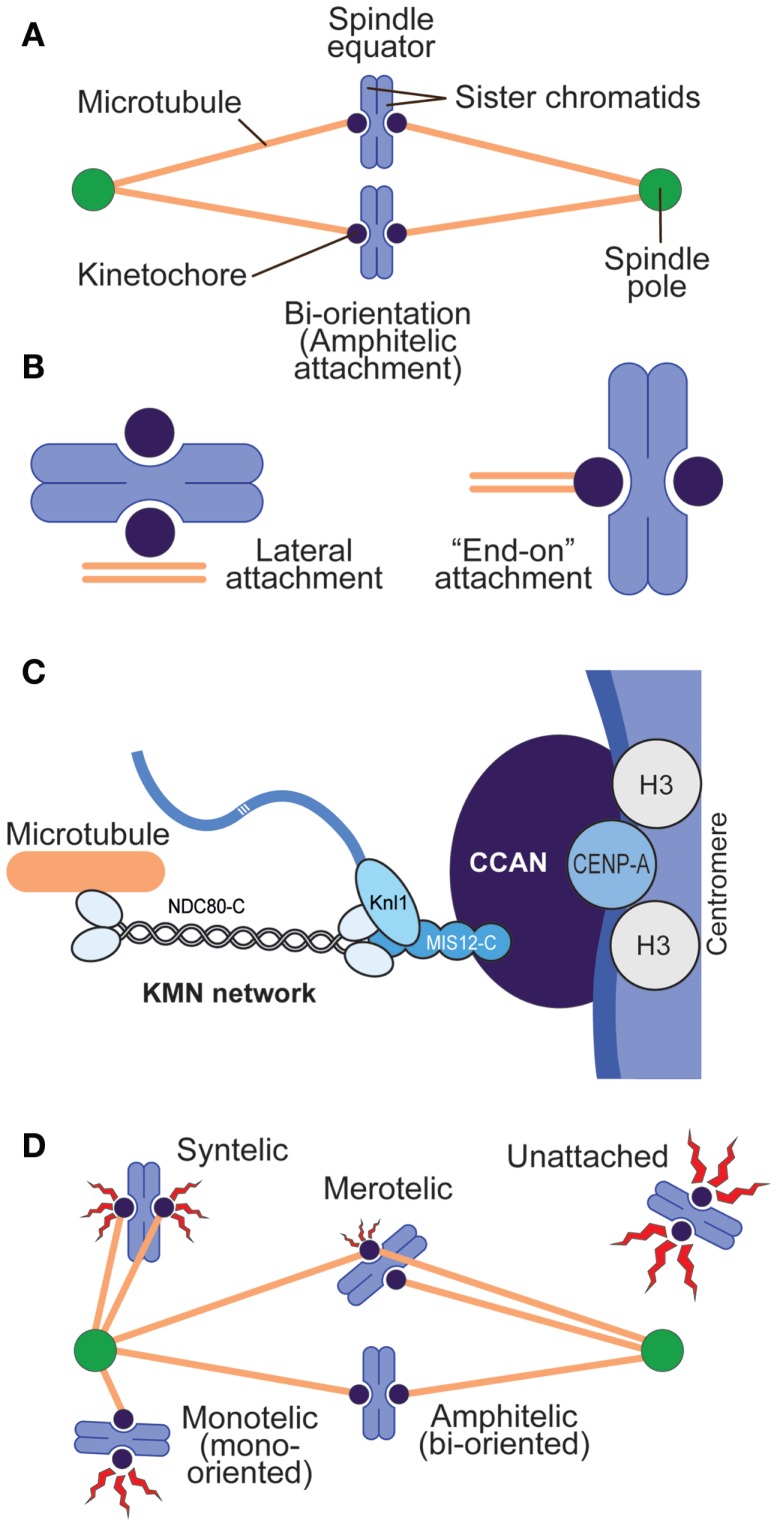

Figure 1.

Chromosome–spindle interactions. (A) A simple spindle with two chromosomes at metaphase. When chromosomes are bi-oriented, the sister chromatids are attached to microtubules, and the microtubules point to opposite spindle poles. (B) Two main modes of kinetochore–microtubule attachment predominate in mitosis. Lateral attachment (left) to the microtubule lattice (as opposed to the microtubule end) is typical of early phases of chromosome congression to the equatorial plane of the mitotic spindle and may not fully engage the core kinetochore machinery devoted to microtubule binding but rather molecular motors (7). “End-on” attachment (right) is typical of the final stages of attachment and involves core kinetochore machinery. (C) Schematic depiction of centromeres and kinetochores. Centromeres host CENP-A, the histone H3 variant, at much higher levels than other segments of the chromosome. CENP-A binds to a subset of 16 or 17 CCAN subunits, collectively represented as a blue oval. The KMN network binds directly to microtubules. (D) Various types of kinetochore–microtubule attachment modes, including erroneous attachments that require correction and that will engage the spindle assembly checkpoint (red flashes). Different “offenses” may provide a graded checkpoint response (variable size of the red flash), with lack of attachment providing a more robust response and merotelic attachment a weak one.