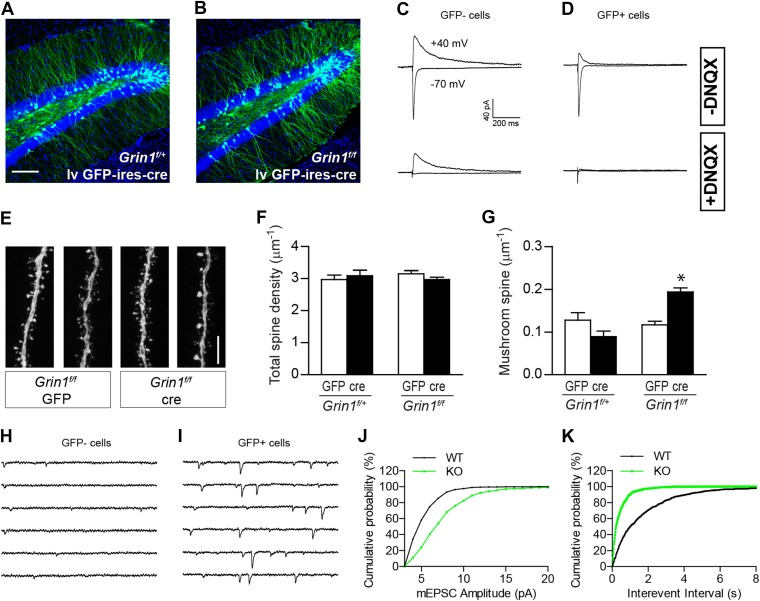

Figure 5. The effect of NR1 KO in mature GCs.

(A, B) Representative images of mature GCs in Grin1f/+ (A) and Grin1f/f (B) mice targeted by lv CAG-GFP-ires-cre. (C, D) Electrophysiological recordings of mature GCs in lv CAG-GFP-ires-cre-targeted mice. GFP− and GFP+ cells represent NR1 WT and KO GCs, respectively. (E) Representative images of dendritic processes in the outer molecular layer of GFP+ cells targeted by lv CAG-GFP and GFP-ires-cre. (F) NR1 KO mature GCs display similar total spine density as wild type GCs. (G) Mushroom spine density was increased in NR1 KO mature GCs (*p < 0.0001). (H, I) Sample traces of AMPAR-mediated mEPSCs in GFP− and GFP+ mature GCs in Grin1f/f mice targeted by lv CAG GFP-ires-cre. (J, K) Cumulative plots of mEPSC amplitude (J) and frequency (K) confirmed that AMPAR-mediated activity was enhanced in NR1 KO mature GCs. Scale bars: 100 µm (A, B) and 5 µm (E).