Abstract

Corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis is the most common form of secondary osteoporosis and the first cause in young people. Bone loss and increased rate of fractures occur early after the initiation of corticosteroid therapy, and are then related to dosage and treatment duration. The increase in fracture risk is not fully assessed by bone mineral density measurements, as it is also related to alteration of bone quality and increased risk of falls. In patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a treat-to-target strategy focusing on low disease activity including through the use of low dose of prednisone, is a key determinant of bone loss prevention. Bone loss magnitude is variable and there is no clearly identified predictor of the individual risk of fracture. Prevention or treatment of osteoporosis should be considered in all patients who receive prednisone. Bisphosphonates and the anabolic agent parathyroid hormone (1–34) have shown their efficacy in the treatment of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis. Recent international guidelines are available and should guide management of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis, which remains under-diagnosed and under-treated. Duration of antiosteoporotic treatment should be discussed at the individual level, depending on the subject's characteristics and on the underlying inflammation evolution.

Keywords: Cytokines, Inflammation, Osteoporosis, Rheumatoid Arthritis

Key messages.

Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (GIOP) is the most common cause of secondary osteoporosis, the most common cause before 50 years of age, and the most common iatrogenic cause of the disease.

Previous and current exposure to glucocorticoids (GCs) increases the risk of fracture and bone loss.

The increase in fracture risk is not fully assessed by bone mineral density measurements, as it is also related to alteration in bone quality and increased risk of falls.

Prevention or treatment of osteoporosis should be considered in all patients who receive GCs.

Recent international guidelines are available and should guide management of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis, which remains under-diagnosed and under-treated.

Introduction

Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (GIOP) is the most common cause of secondary osteoporosis, the first cause before 50 years and the first iatrogenic cause of the disease.1 Prior and current exposure to glucocorticoids (GCs) increases the risk of fracture and bone loss. A key point is that the underlying inflammation for which GCs are used also has a role in bone fragility, as there is a strong relationship between inflammatory cells and bone cells.2 This is one of the determinants of rapid bone loss occurring at the initiation of GCs.

The prevalence of use of oral GCs in the community population is between 0.5 and 0.9% (65% women), rising to 2.7% in women aged ≥50 years.3–5 In the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW), conducted in 10 countries, 4.6% of 60 393 postmenopausal women were receiving GCs at baseline visit.6 7 The main causes of GC use are inflammatory rheumatic disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatic…) and lung disorders (asthma and chronic obstructive lung diseases). Apart from bone and ocular side effects, lipodystrophy and neuropsychiatric disorders are also common adverse events of long-term GC therapy.4

A number of guidelines for GIOP are now available, but the proportion of GC-treated patients receiving preventatives for bone complications remains low. Paradoxically, the numbers of underlying comorbidities and concomitant treatments are strong determinants of the absence of prevention of GIOP, although they are themselves added risk factors for osteoporosis.8–11 There has been greater awareness of this condition in recent years, with improvement in the number of patients receiving bisphosphonates.12 However, even interventions by pharmacist do not significantly improve these numbers,13 and recent studies confirm the neglecting of osteoporosis prophylaxis in patients exposed to GCs.

Pathogenesis

Bone fragility in GIOP is characterised by rapidity of bone loss at the introduction of GCs, and the discrepancy between bone mineral density (BMD) and risk of fractures. These two points can be explained by the pathogenesis of GIOP.

Role of underlying inflammation

In the general population, even small elevations of C reactive protein within the normal range increase non-traumatic fracture risk.14 In some studies, variations within the low levels of inflammatory markers and cytokines predict bone loss and elevated inflammatory markers are prognostic for fractures.15 16

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) doubles the risk of hip and vertebral fractures, regardless of the use of GCs,17 and disease activity is consistently associated with low BMD. In a prospective study of patients with early RA conducted at a time when biotherapies were not available, high bone loss was observed, mainly in patients with persistent inflammation during follow-up (ie, persistent high CRP).18 In ankylosing spondylitis, an inflammatory disease in which GCs are not used, there is bone loss and an increased risk of vertebral fractures, driven by inflammation.19 20

There is a strong biological rationale for these clinical observations. Osteoclastogenesis is under the control of RANK-ligand, which is produced by osteocytes in normal bone remodelling, but also by lymphocytes and fibroblasts in other situations, such as oestrogen deficiency21 and inflammation. Osteoclastogenesis can be enhanced by a number of cytokines, the main pathway being driven by Th 17 cells subpopulation (ie, interleukin (IL) 6 and IL23).22–26 Tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) transgenic mice are models of osteoporosis with dramatic decrease in bone mass and deterioration of bone microarchitecture. Moreover, an over expression of sclerostin has been observed in these models, with a consequence of inflammation-related decrease in bone formation.27 Finally autoimmunity has a role in bone remodelling, as antibodies against citrullinated proteins (ACPAs) can increase osteoclast numbers and activity through citrullinated vimentin located at the surface of precursors and cells (through a TNF-α local effect).28

All these clinical observations and biological studies show that inflammation has a deleterious effect on bone remodelling, inducing an increase in resorption and a decrease in formation, before any effect of GCs themselves.

Bone effects of GCs

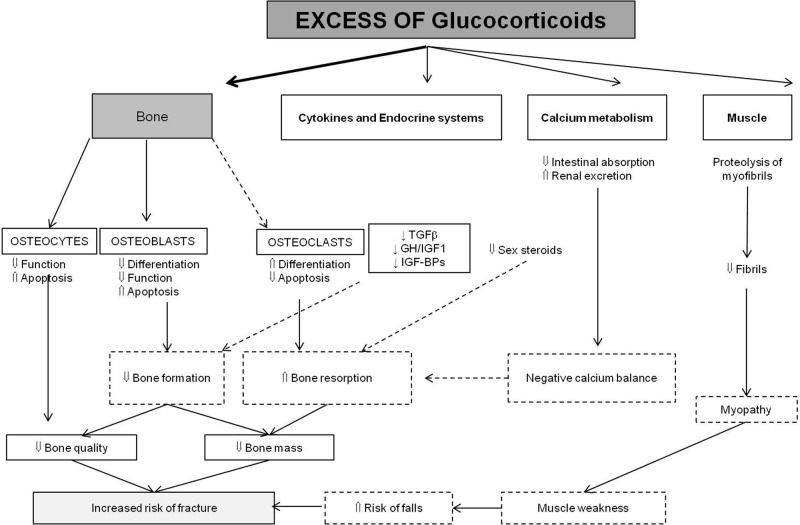

The predominant effect of GCs on bone is the impairment in bone formation (figure 1).29 The evidence that this is a direct effect, independent of the inflammation effect, comes from studies conducted in healthy volunteers: prednisone 5 mg daily is enough to rapidly and significantly decrease serum P1NP and osteocalcin, which are specific markers of bone formation; the changes are reversed after discontinuation of the prednisone.30

Figure 1.

Pathophysiology of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (adapted from ref 29).

GCs at high concentrations dramatically decrease bone formation rate, osteoblast numbers, and osteocyte numbers and activity.31–33 The decrease in osteoblast differentiation includes induction of adipogenetic transcription factors (PPARγ) and suppression of Wnt protein signalling;34–37 the increase of osteoblast and osteocyte apoptosis is associated with caspase 3 activation.38 Moreover, the osteoblast function is decreased through the antianabolic effects of GCs, such as decrease in GH, IGF1 and IGFBP3-4-5. In contrast, GCs increase IGFBP6 transcription thus decreasing IGF2, another local regulator of osteoblast function. GCs are associated with a decrease in osteocyte viability, including changes in matrix properties surrounding the osteocyte lacunae.31

GCs increase the expression of RANK-ligand and decrease the expression of osteoprotegerin in stromal and osteoblastic cells.39 As a consequence, a prolonged lifespan of osteoclasts is observed (contrasting with the decrease in the lifespan of osteoblasts). Although this increased resorption has been demonstrated, much of the GC-related bone loss is caused by the reduced bone formation, which persists throughout GC administration.

Indirect effects of GCs

Earlier, emphasis had been placed on the effects of GCs on calcium metabolism, because of decrease of gastrointestinal absorption of calcium and induction of renal calcium loss. A secondary hyperparathyroidism has been suggested as a determinant of bone effects. Actually, there is no evidence for elevated endogenous levels of PTH in these patients and histological features are not those related to an increased PTH secretion.40

GCs reduce production of sex steroid hormones, and hypogonadism can by itself induce increased bone resorption.29

Glucocorticoid-induced myopathy is related to a direct effect on muscle mass and muscle force; muscle weakness is one of the determinants of the risk of falls and fractures in these patients.29

Differential sensitivity to GCs

There is great variability of side effects of GCs among individuals, including bone loss, for largely unknown reasons. Attention has been paid to the 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (11β-HSD) system, which is a prereceptor modulator of GC action. This system catalyses the interconversion of active/inactive cortisone, and the 11β-HSD1 enzyme amplifies GC signalling in osteoblasts. Interestingly, β11-HSD, widely expressed in GC target tissues including bone, can be modulated and amplified by proinflammatory cytokines,41 42 age and GC administration itself, suggesting that the mechanism could be a key regulator of the effects of GCs on bone. Individual GC sensitivity can also be regulated by polymorphisms in the GC receptor gene.43

Epidemiology

The risk of fractures is increased by twofold in patients with GCs, and the risk of vertebral fractures is even higher. In a study comparing 244 235 oral GC users and 244 235 controls, the risk of hip fracture is 1.6, and that of vertebral fracture is 2.6; these numbers have been reproduced in many studies.44–46 The global prevalence of fractures in patients receiving long-term GCs has been reported to be 30–50%. In 551 patients receiving long-term GCs, the prevalence of vertebral fractures was 37%, with 14% of patients having 2 or more asymptomatic vertebral fractures; 48% of patients aged ≥70 years and 30% of those aged <60 years had at least one VF.47 The prevalence increases with age, a key point for preventive strategies.

A number of observations from epidemiological studies are relevant for clinical practice, as they could help to identify a high-risk group of patients.

Time effect

The increase in fracture risk is immediate, as early as 3 months after the initiation of therapy and reverses sharply after discontinuation of GCs.45 This cannot be explained by BMD changes, but can be related to the added effects of GCs on bone remodelling previously uncoupled by the inflammation itself, and the dramatic effect on bone strength through induced apoptosis of osteocytes. Data also suggest a rapid increase in rate of falls after start of oral GCs.45 Thus primary prevention, after careful assessment of the fracture risk, is recommended in high-risk patients.

Dose effect

In epidemiological studies, the increased risk of fractures is observed even at low doses of prednisone, that is, 2.5–5 mg per day. The appropriate care of patients receiving such low doses is not well defined. There is a dose-dependent increase in fracture incidence. Interestingly, the fracture risk is related to the current daily dose, more than to the cumulative dose;48 this may be related to the difficulty of an accurate calculation of this cumulative dose.

Prior versus current GCs use

Ever use of GCs is associated with an increased risk of hip fracture, and this justifies the assessment of osteoporosis and fracture risk in all patients. However, the risk is mainly associated with recent and prolonged GC use, more than to remote or short courses.49

BMD loss

BMD loss is an immediate consequence of the introduction of GCs and affects the trabecular bone (ie, spine) more than it does the cortical bone (ie, femur). According to a meta-analysis of 56 cross-sectional studies and 10 longitudinal studies, bone loss assessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, can be 5–15% during the first year of treatment.44 The main determinant of BMD at any time is the cumulative dose. The increased rate of bone loss persists in chronic GC users, but more slowly.

Assessment of fracture risk

Role of BMD

There is a mismatch between BMD data and fracture data in patients receiving GCs because of the disparity related to the alteration of bone quality. At similar levels of BMD, postmenopausal women taking GCs have considerably higher risk of fracture than controls not using GCs. There is a debate on the appropriate T score threshold to be considered a risk and as an indication for treatment in patients with GCs: the same diagnostic criterion as in postmenopausal women has been suggested (T≤−2.5),50 but a higher threshold (ie, T≤−1.5) has been proposed for intervention,46 because bone loss can be 10% or more in some individuals over the first year of GC use. There is no means to provide an evidence-based threshold for treatment decisions. A practical approach is to recommend a BMD measurement in GC users (optimally at the initiation of treatment) and to consider that patients with T ≤−2.5 as those who should receive the highest priority for treatment.51 However, beyond the BMD, a more comprehensive approach of the risk and clinical judgement is needed.

Role of FRAX

The WHO fracture risk assessment tool (FRAX) algorithm has been developed to estimate the 10-year risk of hip and other major fractures (clinical spine, humerus or wrist fracture) based on clinical risk factors, with or without BMD.52 The risk factors included in FRAX are: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), personal history of fracture, parental history of hip fracture, current smoking, alcohol intake, glucocorticoid use, rheumatoid arthritis, other causes of secondary osteoporosis and femoral neck (not spine) BMD. These clinical risk factors are largely independent of BMD and can thus improve the fracture risk assessment. FRAX cannot be used in premenopausal women, men aged <40 years and in subjects previously treated with antiosteoporotic drugs.

One of the limitations of FRAX is that use of oral GCs is entered as a dichotomous risk factor and does not take into account the dose of GCs and the duration of use. Moreover, FRAX does not take into account the difference in risk between prior and current use.49 FRAX assumes an average dose of prednisolone (2.5–7.5 mg/day or its equivalent) and may underestimate fracture risk in patients taking higher doses and may overestimate risk in those taking lower doses. Moreover the predictive value of FRAX has been mainly validated for non-vertebral fractures although the principal risk in GCs users is for vertebral fractures. Adjustment of FRAX has been proposed for postmenopausal women and men aged ≥50 years with lower or higher doses than 2.5–7.5 mg/day: a factor of 0.8 for low-dose exposure and 1.15 for high-dose exposure for major osteoporotic fractures, and 0.65 and 1.20 for hip fracture probability.53 For very high doses of glucocorticoids, greater upward adjustment of fracture probability may be required.

FRAX assessment has already been included in some guidelines at different steps of the treatment decision. American College of Rheumatology guidelines recommend treatment in postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years or older starting oral glucocorticoids with a FRAX-derived 10-year probability of major osteoporotic fracture of over 10%, and in those with a probability of less than 10% if the daily dose of prednisolone or its equivalent is ≥7.5 mg/day.54 According to the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF)–European Calcified Tissue Society55 recommendations, a treatment decision for postmenopausal women and for men aged ≥50 years exposed to oral glucocorticoids for ≥3 months should be based on fracture risk assessment with FRAX adjusted for glucocorticoid use (with or without BMD testing). Treatment can be considered directly (without FRAX assessment) if patients are at high risk defined by one of the following criteria: prevalent fracture, age ≥70 years, exposure to a glucocorticoid dose ≥7.5 mg per day or low BMD (T≤−2.5).55

Role of underlying disease

Persistent inflammation is associated with bone loss as shown in longitudinal studies in patients with active RA or ankylosing spondylitis (SpA). In contrast, prospective open studies show that complete control of inflammation (in parallel with clinical improvement and thus increased mobility) is accompanied by the absence of bone loss.56 This is expected in SpA in the absence of GCs, but is also observed in RA of the hand, spine and hip, in patients receiving low doses of GCs.56–58 In the BeSt study, conducted in patients with recent-onset active RA, bone loss was limited in all treated groups, including in the group initially treated with high-dose prednisone.59 Thus, the concept that a high level of inflammation is more deleterious for bone than a low dose of GCs, controlling this inflammation is relevant as far as surrogate markers (BMD, biological parameters) are concerned. However, there is no evidence for a reduction in fracture risk with such a strategy,60 and new epidemiological studies are mandatory in this matter.

Role of patient characteristics

Age, female gender, low BMI, history of falls and previous fractures, duration of menopause and smoking are associated with fracture risk in patients with GCs, similarly to how they are in primary osteoporosis. We have shown that prevalence of non-vertebral fractures is a strong determinant of the risk of having vertebral fractures in patients with RA,61 implying that the individual's skeleton is already of inadequate strength to withstand the trauma of daily living. Beyond GC use, these risk factors must be assessed in all patients, and all causes of secondary osteoporosis are added risk factors of fractures in patients with GCs.

Treatment

General measures

At the initiation of GC treatment, the patient's height must be measured, as height loss in the follow-up could be related to asymptomatic vertebral fractures. Biological tests are performed to screen for other causes of bone diseases. There is no indication for assessment of biochemical markers of bone remodelling either at baseline or during follow-up, as bone turnover is consistently low in GC users.

As the daily dose of GCs is a determinant of fracture risk, it must be constantly reviewed by considering both the reduction of the dose to the minimally active and alternative administration such as intra-articular injections.

The risk of falling should be assessed in particular in elderly patients, patients with painful joints of the lower limbs and patients with massive doses of GCs. Physical activity or mobilisation should be considered, adapted to the underlying condition.

Attention to nutrition must be paid to prevent protein and calcium intake deficiencies. Calcium and vitamin D have been used for decades in GIOP, although there are controversies about their effect on BMD. In 66 patients with RA receiving prednisone, 1000 mg/day of calcium carbonate and 500 IU/day of vitamin D3 induced a positive change of 0.63% per year at the lumbar spine, versus a decrease of 1.31% per year in the placebo group; there was no effect at the femoral neck.62 No benefit was observed in another study with a 3-year follow-up.63 However, it is reasonable to consider that any deficiency in calcium and vitamin D could be deleterious in patients beginning or receiving GCs. For calcium, the recommendation is to have an intake of 1000–1500 mg/day, and supplementation should be prescribed only to patients whose dietary intake does not provide this adequate quantity. GC-treated patients may seldom be outdoors, and thus exposed more than the general population to vitamin D deficiency. Supplementation is adequate between 800 and 2000 IU per day. There is no evidence of an advantage using calcitriol or alcalcidol, as there is a large variability of outcomes with these vitamin D metabolites over plain vitamin D.

Pharmacological treatment

Bisphosphonates and teriparatide have been assessed in prevention and treatment of GIOP. There are a number of issues regarding their efficacy. Fracture incidence has not been a primary end point of any study (the end point being BMD), the duration of the studies is low (1 year on average) and the number of men and premenopausal women in these studies is low. Thus the efficacy on fractures is mainly based on bridging data between the short-term change in BMD in patients with GCs, and the long-term change in BMD and reduction of fracture risk in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Bisphosphonates are the more popular antiosteoporotic drugs. Alendronate (oral 5 or 10 mg once daily, or 70 mg once weekly), risedronate (oral 5 mg daily or 35 mg one weekly) and zoledronate (intravenous infusion 5 mg once yearly) prevent bone loss at the spine and hip in patients initiating GCs, and increase BMD in patients on long-term GCs. Alendronate was assessed in a placebo controlled study in 477 men and women over 48 weeks. There was a 2.1 and 2.9% increase at the lumbar spine in the 5 and 10 mg alendronate groups, respectively and a 0.4% decrease in the placebo group. At the femoral neck the changes were +1, +1.2 and −1.2%, respectively. Interestingly the decrease of BMD in the placebo group (receiving calcium and vitamin D) was driven by the duration of GCs: −2.9, −1.4, +0.8 in patients receiving GCs for less than 4 months, 4–12 months and more than 12 months, respectively.64 In a follow-up study in a second year, performed in 208 out of the 477 patients, there were fewer patients with new vertebral fractures in the treated group (0.7%) than in the placebo group (6.8%).65 Two 1-year studies were performed with risedronate, one for prevention in patients beginning GCs, and one in treatment of GIOP in patients chronically treated with GCs. Data from pooling these two studies suggest a reduction of fractures in the first year of therapy: 16% of placebo patients and 5% of those on risedronate 5 mg/day.66–68 In a comparative double blind randomised study, zoledronic acid (1 injection) induced a higher BMD increase than risedronate (daily) in treatment (+4.06 vs +2.71%) and prevention (+2.6 vs 0.6%) subgroups over 1 year at the lumbar spine.69

Attention has been paid recently to osteonecrosis of the jaw and atypical femoral fractures such as side effect of long-term administration of antiresorptive drugs in osteoporosis; these events are very rare,70 71 but GC use is one of the identified risk factors. Buccal hygiene procedures should be implemented to prevent any local increased risk of infection. Whether these rare events can change the duration of anti-resorptive treatments in long-term GC users needs further studies. Bisphosphonates should be used cautiously in premenopausal women, as they cross the placenta; appropriate contraception must be used if necessary and preference given to a short bone half-life bisphosphonate.

The use of administrative databases offers the opportunity to assess a huge number of patients, taking into account the methodological issues related to these studies (retrospective design, lack of details in patient characteristics, absence of confirmation of the diagnosis of fractures, etc). Two well-designed studies with such an approach, suggest the efficacy of bisphosphonates in reducing fractures and a better efficacy when the antiosteoporosis medication is initiating within 90 days of chronic GC use, reaching a 48% reduction rate of fracture.72 73 However, not all studies support these conclusions, and there is still a disconnect between GIOP care and improvement of outcomes.74

There is so far no study of denosumab on GIOP. In a subgroup analysis of a 12-month study of patients with RA (still active although they were receiving methotrexate) treated with denosumab, BMD increases were similar in patients with and without GCs.75 Such data are relevant for use of denosumab in patients with contraindications for bisphosphonates, such as renal insufficiency.

GIOP is a condition where the principal cause of bone loss is reduction in bone formation. This is the rationale for using teriparatide, a parathyroid hormone peptide producing anabolic skeletal effects by stimulation of bone formation. In a 18-month randomised trial conducted in patients with GIOP, teriparatide 20 µg daily was compared to alendronate 10 mg daily; as expected, the increase in BMD was higher with the anabolic agent as compared to the antiresorptive one (7.2% vs 3.4% at the lumbar spine). More importantly, a significantly lower number of vertebral fractures was observed: 0.6% and 6.1% in the teriparatide and alendronate groups, respectively.76 77 Data were confirmed over 36 months.

There are a number of guidelines published by different national societies and colleges, on use of pharmacological treatment in GIOP, which vary somewhat.51 78–80 However, all of them stress the early increase in the risk of fracture at the initiation of glucocorticoids, and the importance of recognition of patients at high risk of fracture; for such patients (elderly subjects, already osteoporotic patients, those on high doses of GCs), primary prevention using bisphosphonates is always recommended.

Follow-up

Adherence to antiosteoporotic treatment may be low in some patients who are already taking multiple medications, and should be assessed regularly. Height loss can be related to vertebral fractures, sometimes asymptomatic because of the analgaesic property of GCs. There is no guideline about the use of BMD measurement; in clinical practice it could be useful to check for any bone loss 1 or 2 years after initiation of treatment.

Conclusion

We should not go on neglecting fracture risk in patients with GCs. This risk must be assessed in all patients at the initiation of prolonged GC therapy. The treat-to-target strategy focusing on low disease activity is effective on bone loss in RA. New epidemiological data are needed to assess the benefit of such a strategy on fracture incidence.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Kok C, Sambrook PN. Secondary osteoporosis in patients with an osteoporotic fracture. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2009;23:769–79. 10.1016/j.berh.2009.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roux C. Osteoporosis in inflammatory joint diseases. Osteoporos Int 2011;22:421–33. 10.1007/s00198-010-1319-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soucy E, Bellamy N, Adachi JD et al. . A Canadian survey on the management of corticosteroid induced osteoporosis by rheumatologists. J Rheumatol 2000;27:1506–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fardet L, Petersen I, Nazareth I. Prevalence of long-term oral glucocorticoid prescriptions in the UK over the past 20 years. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:1982–90. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Overman RA, Yeh JY, Deal CL. Prevalence of oral glucocortidoid usage in the United States: a general population perspective. Arthr Care Res 2013;65:294–8. 10.1002/acr.21796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Díez-Pérez A, Hooven FH, Adachi JD et al. . Regional differences in treatment for osteoporosis. The Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). Bone 2011;49:493–8. 10.1016/j.bone.2011.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silvermann S, Curtis J, Saag K et al. . International management of bone health in glucocorticoid-exposed individuals in the observational GLOW study. Osteoporos Int 2015;26:419–20. 10.1007/s00198-014-2883-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feldstein AC, Elmer PJ, Nichols GA et al. . Practice patterns in patients at risk for glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2005;16:2168–74. 10.1007/s00198-005-2016-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzman-Clark JR, Fang MA, Sehl ME et al. . Barriers in the management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:140–6. 10.1002/art.22462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon DH, Katz JN, Jacobs JP et al. . Management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: rates and predictors of care in an academic rheumatology practice. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:3136–42. 10.1002/art.10613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yood RA, Harrold LR, Fish L et al. . Prevention of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1322–7. 10.1001/archinte.161.10.1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duyvendak M, Naunton M, Atthobari J et al. . Corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis prevention: longitudinal practice patterns in The Netherlands 2001–2005. Osteoporos Int 2007;18:1429–33. 10.1007/s00198-007-0345-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klop C, de Vries F, Vinks T et al. . Increase in prophylaxis of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis by pharmacist feedback: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:385–92. 10.1007/s00198-013-2562-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schett G, Kiechl S, Weger S et al. . High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and risk of non traumatic fractures in the Bruneck study. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:2495–501. 10.1001/archinte.166.22.2495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding C, Parameswaran V, Udayan R et al. . Circulating levels of inflammatory markers predict change in bone mineral density and resorption in older adults: a longitudinal study. J Clinical Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:1952–8. 10.1210/jc.2007-2325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cauley JA, Danielson ME, Boudreau RM et al. , for the Health ABC study. Inflammatory markers and incident fracture risk in older men and women: the Health Aging and Body Composition Study. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22:1088–95. 10.1359/jbmr.070409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Staa TP, Geusens P, Bijlsma JW et al. . Clinical assessment of the long-term risk of fracture in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3104–12. 10.1002/art.22117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gough AK, Lilley J, Eyre S et al. . Generalised bone loss in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 1994;344:23–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91049-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maillefert JF, Aho LS, El Maghraoui A et al. . Changes in bone density in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a two-year follow-up study. Osteoporos Int 2001;12:605–9. 10.1007/s001980170084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Briot K, Durnez A, Paternotte S et al. . Bone oedema on MRI is highly associated with low bone mineral density in patients with early inflammatory back pain: results from the DESIR cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1914–19. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charactcharoenwitthaya N, Khosla S, Atkinson EJ et al. . Effect of blockade of TNF-α and interleukine-1 action on bone resorption in early postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Res 2007;22: 724–9. 10.1359/jbmr.070207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong YY, Feige U, Sarosi I et al. . Activated T cells regulate bone loss and joint destruction in adjuvant arthritis through osteoprotegerin ligand. Nature 1999;402:304–9. 10.1038/46303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaiss MM, Axmann R, Zwerina J et al. . Treg cells suppress osteoclast formation. A new link between the immune system and bone. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:4104–12. 10.1002/art.23138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lam J, Takeshita S, Barker JE et al. . TNFα induces osteoclastogenesis by direct stimulation of macrophages exposed to permissive levels of RANK ligand. J Clin Invest 2000;106: 1481–8. 10.1172/JCI11176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato K, Suematsu A, Okamoto K et al. . Th17 functions as an osteoclastogenic helper T cell subset that links T cell activation and bone destruction. J Exp Med 2006;203:2673–82. 10.1084/jem.20061775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Axmann R, Böhm C, Krönke G et al. . Inhibition of interleukin-6 receptor directly blocks osteoclast formation in vitro and in vivo. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:2747–56. 10.1002/art.24781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen XX, Baum W, Dwyer D et al. . Sclerostin inhibition reverses systemic, periarticular and local bone loss in arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1732–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harre U, Georgess D, Bang H et al. . Induction of osteoclastogenesis and bone loss by human autoantibodies against citrullinated vimentin. J Clin Invest 2012;122:1791–802. 10.1172/JCI60975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canalis E, Mazziotti G, Giustina A et al. . Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: pathophysiology and therapy. Osteoporos Int 2007;18:1319–28. 10.1007/s00198-007-0394-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ton FN, Gunawardene SC, Lee H et al. . Effects of low-dose prednisone on bone metabolism. J Bone Miner Res 2005;20:464–70. 10.1359/JBMR.041125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lane NE, Yao W, Balooch M et al. . Glucocorticoid-treated mice have localized changes in trabecular bone material properties and osteocyte lacunar size that are not observed in placebo-treated or estrogen-deficient mice. J Bone Miner Res 2006;21:466–76. 10.1359/JBMR.051103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, Parfitt AM et al. . Inhibition of osteoblastogenesis and promotion of apoptosis of osteoblasts and osteocytes by glucocorticoids. Potential mechanisms of their deleterious effects on bone. J Clin Invest 1998;102:274–82. 10.1172/JCI2799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira RC, Delany AM, Canalis E. Effects of cortisol and bone morphogenetic protein-2 on stromal cell differentiation: correlation with CCAAT-enhancer binding protein expression. Bone 2002;30:685–91. 10.1016/S8756-3282(02)00687-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ito S, Suzuki N, Kato S et al. . Glucocorticoids induce the differentiation of a mesenchymal progenitor cell line, ROB-C26 into adipocytes and osteoblasts, but fail to induce terminal osteoblast differentiation. Bone 2007;40:84–92. 10.1016/j.bone.2006.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Brien CA, Jia D, Plotkin LI et al. . Glucocorticoids act directly on osteoblasts and osteocytes to induce their apoptosis and reduce bone formation and strength. Endocrinology 2004;145:1835–41. 10.1210/en.2003-0990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohnaka K, Tanabe M, Kawate H et al. . Glucocorticoid suppresses the canocical Wnt signal in cultured human osteoblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005;329:177–81. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang FS, Lin CL, Chen YJ et al. . Secreted frizzled-related protein 1 modulates glucocorticoids attenuation of osteogenic activities and bone mass. Endocrinology 2005;146:2415–23. 10.1210/en.2004-1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Porta A, Peng X et al. . Prevention of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis in osteocytes and osteoblasts by calbindin-D28k. J Bone Miner Res 2004;19:479–90. 10.1359/JBMR.0301242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swanson C, Lorentzon M, Conaway HH et al. . Glucocorticoid regulation of osteoclast differentiation and expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB) ligand, osteoprotegerin, and receptor activator of NF-kappaB in mouse calvarial bones. Endocrinology 2006;147:3613–22. 10.1210/en.2005-0717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubin MR, Bilezikian JP. The role of parathyroid hormone in the pathogenesis of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: a re-examination of the evidence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002;87:4033–41. 10.1210/jc.2002-012101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cooper MS, Blumsohn A, Goddard PE et al. . 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 activity predicts the effects of glucocorticoids on bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:3874–7. 10.1210/jc.2003-022025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper MS, Bujalska I, Rabbitt E et al. . Modulation of 11 beta-hydroxisteroid dehydrogenase isozymes by proinflammatory cytokines in osteoblasts; an autocrine switch form glucocorticoid inactivation to activation. J Bone Miner Res 2001;16:1037–44. 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.6.1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Russcher H, Smit P, van den Akker ELT et al. . Two polymorphisms in the glucocorticoid receptor gene directly affect glucocorticoid-regulated gene expression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:5804–10. 10.1210/jc.2005-0646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. The epidemiology of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 2002;13:777–87. 10.1007/s001980200084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Abenhaim L et al. . Use of oral corticosteroids and risk of fractures. J Bone Miner Res 2000;15:993–1000. 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.6.993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A et al. . A meta-analysis of prior corticosteroid use and fracture risk. J Bone Miner Res 2004;19:893–9. 10.1359/JBMR.040134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Angeli A, Guglielmi G, Dovio A et al. . High prevalence of asymptomatic vertebral fractures in post-menopausal women receiving chronic glucocorticoid therapy: a cross-sectional outpatient study. Bone 2006;39:253–9. 10.1016/j.bone.2006.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Staa TP, Laan RF, Barton IP et al. . Bone density threshold and other predictors of vertebral fracture in patients receiving oral glucocorticoid therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2003;11:3224–9. 10.1002/art.11283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Majumdar SR, Morin SN, Lix LM et al. . Influence of recency and duration of glucocorticoid use on bone mineral density and risk of fractures: population-based cohort study. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:2493–8. 10.1007/s00198-013-2352-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selby PL, Halsey JP, Adams KRH et al. . Corticosteroids do not alter the threshold for vertebral fracture. J Bone Miner Res 2000;15:952–6. 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.5.952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Briot K, Cortet B, Roux C et al. . 2014 update of recommendations on the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Joint Bone Spine 2014;81:493–501. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX.

- 53.Leib ES, Saag KG, Adachi JD et al. , FRAX(®) Position Development Conference Members. Official Positions for FRAX(®) clinical regarding glucocorticoids: the impact of the use of glucocorticoids on the estimate by FRAX(®) of the 10 year risk of fracture from Joint Official Positions Development Conference of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry and International Osteoporosis Foundation on FRAX(®). J Clin Densitom 2011;14:212–19. 10.1016/j.jocd.2011.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grossman JM, Gordon R, Ranganath VK et al. . American College of Rheumatology 2010 recommendations for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:1515–26. 10.1002/acr.20295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lekamwasam S, Adachi JD, Agnusdei D et al. , Joint IOF-ECTS GIO Guidelines Working Group. A framework for the development of guidelines for the management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:2257–76. 10.1007/s00198-012-1958-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wijbrandts CA, Klaasen R, Dijkgraaf MGW et al. . Bone mineral density in rheumatoid arthritis patients 1 year after adalimumab therapy: arrest of bone loss. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:373–6. 10.1136/ard.2008.091611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haugeberg G, Conaghan PG, Quinn M et al. . Bone loss in patients with active early rheumatoid arthritis: infliximab and methotrexate compared with methotrexate treatment alone. Explorative analysis from a 12-month randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1898–901. 10.1136/ard.2008.106484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haugeberg G, Strand A, Kvien TK et al. . Reduced loss of hand bone density with prednisolone in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from a randomized placebo controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1293–7. 10.1001/archinte.165.11.1293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Güler-Yüksel M, Bijsterbosch J, Goekoop-Ruiterman YP et al. . Changes in bone mineral density in patients with recent onset, active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:823–8. 10.1136/ard.2007.073817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kawai VK, Grijalva CG, Arbogast PG et al. . Initiation of tumor necrosis factor α antagonists and risk of fractures in patients with selected rheumatic and autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:1085–94. 10.1002/acr.21937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ghazi M, Kolta S, Briot K et al. . Prevalence of vertebral fractures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: revisiting the role of glucocorticoids. Osteoporos Int 2012;23:581–7. 10.1007/s00198-011-1584-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buckley LM, Leib ES, Cartularo KS et al. . Calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation prevents bone loss in the spine secondary to low-dose corticosteroids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med 1996;125:961–8. 10.7326/0003-4819-125-12-199612150-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adachi J, Bensen WG, Bianchi F et al. . Vitamin D and calcium in the prevention of corticosteroid induced osteoporosis: a 3 year follow-up. J Rheumatol 1996;23:995–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saag KG, Emkey R, Schnitzer TJ et al. . Alendronate for the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 1999;339:292–9. 10.1056/NEJM199807303390502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adachi JD, Saag KG, Delmas PD et al. . Two-year effects of alendronate on bone mineral density and vertebral fracture in patients receiving glucocorticoids: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled extension trial. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44: 202–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cohen S, Levy RM, Keller M et al. . Risedronate therapy prevents corticosteroid-induced bone loss: a twelve-month, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:2309–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reid DM, Hughes RA, Laan RF et al. . Efficacy and safety of daily risedronate in the treatment of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis in men and women: a randomized trial. European Corticosteroid-Induced Osteoporosis Treatment Study. J Bone Miner Res 2000;15:1006–13. 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.6.1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wallach S, Cohen S, Reid DM et al. . Effects of risedronate treatment on bone density and vertebral fracture in patients on corticosteroid therapy. Calcif Tissue Int 2000;67:277–85. 10.1007/s002230001146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reid DM, Devogelaer JP, Saag K et al. . Zoledronic acid and risedronate in the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis (HORIZON): a multicentre, double-blind, double-dummy, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009;373:1253–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60250-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barasch A, Cunha-Cruz J, Curro FA et al. . Risk factors for osteonecrosis of the jaws: a case-control study from the CONDOR dental PRRN. J Dent Res 2011;90:439–44. 10.1177/0022034510397196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Feldstein AC, Black D, Perrin N et al. . Incidence and demography of femur fractures with and without atypical features. J Bone Miner Res 2012;27:977–86. 10.1002/jbmr.1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomas T, Horlait S, Ringe JD et al. . Oral bisphosphonates reduce the risk of clinical fractures in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int 2013;24:263–9. 10.1007/s00198-012-2060-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Overman RA, Gourlay ML, Deal CL et al. . Fracture rate associated with quality metric-based anti-osteoporosis treatment in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2015. Jan 20. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Majumdar SR, Lix LM, Morin SN et al. . The disconnect between better quality of glucocorticoids-induced osteoporosis preventive care and better outcomes: a population-based cohort study. J Rheumatol 2013;40:1736–41. 10.3899/jrheum.130041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dore RK, Cohen SB, Lane NE et al. , on behalf of the Denosumab RA Study Group. Effects of denosumab one bone mineral density and bone turnover in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving concurrent glucocorticoids or bisphosphonates. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:872–5. 10.1136/ard.2009.112920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saag KG, Shane E, Boonen S et al. . Teriparatide or alendronate in glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2028–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa071408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saag KG, Zanchetta JR, Devogelaer JP. Effects of teriparatide versus alendronate for treating glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: thirty-six-month results of a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:3346–55. 10.1002/art.24879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.National osteoporosis foundation's clinician's guide to the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Washington DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bone and Tooth Society of Great Britain. Guidelines on the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. London: Royale College of Physicians, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rizzoli R, Adachi JD, Cooper C et al. . Management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int 2012;91:225–43. 10.1007/s00223-012-9630-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]