Abstract

Background:

Researchers need to consider the impact and utility of their findings. Film is an accessible medium for qualitative research findings and can facilitate learning through emotional engagement.

Aim:

We aimed to explore the usefulness of a short film presenting findings from a published qualitative synthesis of adults’ experience of chronic musculoskeletal pain for pain education. In particular, we were interested in the impact of the film on clinician’s understanding of patients’ experience of chronic pain and how this knowledge might be used for improved healthcare for people with pain.

Methods:

Focus groups with healthcare professionals enrolled in a pain management foundation course explored healthcare professionals’ experience of watching the film. A constructivist grounded theory approach was adopted by the researchers.

Findings:

This article presents one thematic exemplar from a wider study. Participants reflected upon the pitfalls of judging by appearances and the value of seeing the person beneath his or her performance.

Conclusion:

There is a danger that the impact of qualitative findings is under-valued in clinical education. We present one exemplar from a study exploring knowledge mobilisation, which demonstrates that qualitative research, specifically qualitative films, can make us think about the care that we provide to people with chronic pain.

Keywords: Musculoskeletal pain, chronic pain, qualitative research, knowledge, transfer, patient experience

Background

A recent qualitative systematic review of patients’ experiences of chronic pain demonstrates that patients with chronic pain often feel that they have not been heard by their clinicians.1,2 Although qualitative research can offer insight into patients’ experience for improved care, there are no studies that explore the usefulness of qualitative research findings for pain education. One of the inherent difficulties of evaluating qualitative knowledge mobilisation is that findings are not neatly packaged ‘facts’. There is therefore a real danger that qualitative research is side-lined. The way that we conceptualise knowledge might mean that we underestimate the potential for learning from qualitative research. Therefore, rather than conceptualising knowledge as ‘facts’ to be exchanged, it might be useful to consider knowledge as a process or dialectic.3,4 Central to dialectic theory is the idea that tension and struggle between ideas create new ways of thinking.5 We assimilate knowledge from various sources in order to develop ‘situated judgement’3 or tacit knowledge.6 This resonates with anthropological texts supporting the on-going re-enactment or ‘performance’ of cultural knowledge.7 In short, we can construct knowledge as a verb, rather than as a noun.

To maximise impact, researchers should consider the most effective way to present findings. The use of artistic media, such as film, lends itself to qualitative research. Performative approaches are powerful because they facilitate emotional engagement; they evoke, provoke and stimulate ideas rather than present facts.8 These approaches have been used to facilitate learning and to develop empathetic understanding.9–14 Film can be a succinct, accessible and practical means of disseminating findings.15,16 Existing reviews indicate a need for research to evaluate knowledge mobilised through arts-based research.17,18 Although evidence is scant, examples such as the portrayal of patients’ experience by the Department of Primary Care’s ‘Health Talk Online’ (http://healthtalkonline.org) suggest that film is an acceptable medium for disseminating qualitative findings.

Aims

We aimed to explore the usefulness of a short qualitative film presenting findings from a published qualitative synthesis of adults’ experience of chronic musculoskeletal pain for pain education.1,2 In particular, we were interested in the impact of the film on clinician’s understanding of patients’ experience of chronic pain and how this knowledge might be used for improved healthcare for people with pain. In this article, we focus on one exemplar of findings to illustrate the potential impact of qualitative research on the management of chronic pain.

Method

Research context

The film ‘Struggling to be me’ (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FPpu7dXJFRI) was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research (NIHR HS&DR) Programme as an output from a qualitative synthesis.2 The film has received more than 8200 hits on YouTube since November 2013. As a result of a subsequent collaboration between FT and SJ, the film was delivered as part of an evidence-based ‘bio-psychosocial’ module content, within an MSc Level, e-learning module, ‘Foundation in Primary Care Pain Management’. The module runs over 14 weeks, and the film was released to the student cohort at 6 weeks, in line with the module assessment period.

Ethics

We obtained ethical permission from the University ethics board. We have chosen not to identify narratives by professional grouping to protect participants’ anonymity.

Sample

All 19 healthcare professionals consented to be involved. These included mostly general practitioners alongside nurses, pharmacists, a physiotherapist and a psychiatrist. All worked in the United Kingdom within primary care or in partnership with it. All had an interest in the management of patients with chronic pain.

Data collection

Six interviews including 19 participants took place on ‘ooVoo’, a video chat and instant messaging application that allows verbatim recording. Interviews took place at convenient times between January 2014 and February 2014. In all, 17 participants were interviewed in focus groups (three groups of four and one group of five). The remaining two participants were interviewed individually as we were unable to schedule a suitable time or had difficulties with the online connection.

Although there are limitations to online interviews (e.g. impact on non-verbal communication), there are some advantages. Importantly, it allows you to access geographically disparate participants. Students were asked to (a) watch the film ‘Struggling to be me’, (b) think about relevant themes, for example, how you felt when watching the film? or any changes that you might make to your clinical practice? and (c) attend an online focus group to explore their experience of watching the film. Focus groups were facilitated by SJ. One other researcher attended the groups to record observations or to assist in the event of technical hitches. Focus group time was limited to approximately 1 hour. Recordings were transcribed verbatim and transcripts loaded onto NVivo 9 software19 for qualitative analysis.

Analysis

This study was set within a constructivist grounded theory framework,20 taking the stance that knowledge is not ‘discovered’ but co-constructed by researcher and participants. An iterative process of comparing data, codes and categories enables the researcher to move from an initial tentative category towards progressively abstracted theoretical categories that are grounded in the data. FT and SJ challenged each other’s emerging interpretation to ensure interpretive rigour.21

Findings – struggling to perform pain

We found several themes that illustrate the learning potential of qualitative research films for clinical practice. Participants discussed (a) a growing identification of a person beneath his or her performance of pain, (b) feeling bombarded by despair as a clinician and the need to balance empathy with ‘not getting too involved’, (c) recognising the pitfalls of the medical model that aims to ‘fix’ illness and (d) the need to reconstruct the clinical encounter as a shared journey towards healing.

This report focuses on one thematic exemplar – ‘Struggling to perform pain’ to demonstrate the potential usefulness of film as a succinct knowledge mobilisation medium for qualitative findings. This theme was derived from the original qualitative synthesis and was performed in the film.1,2 It describes a cultural etiquette, or ‘right way’, of being in pain which attempts to strike a balance between appearing credible and holding onto a sense of self. Participants discuss the pitfalls of judging by appearances and the value of seeing the person beneath his or her performance.

The pitfalls of judging pain by appearance

Participants discuss how appearance does not necessarily represent the true impact of pain and the value of recognising this in the clinical encounter:

One of the things that struck me and it’s very, very true to life … [pain] isn’t immediately obvious to other people … you can present a normal external appearance and yet be suffering dreadfully inside.

It’s very easy to take people on face value … especially in a very short consultation, but you know we are doing them [patients] a dis-service by doing that aren’t we?

We need to make everybody aware that even though some people look fine, they may be beautifully made up, they may be very well-dressed, but they may be suffering underneath.

However, at the same time, participants discussed how the actor’s appearance did not match her description of pain. This mismatch threatened her credibility and represents a tension in the narratives: that is, although recognising that appearances are misleading, we are influenced by what we see:

If I could just make a cold clinical observation … there really was an incongruity between the symptoms … portrayed verbally and what she was actually doing … She was able to walk on the promenade she was able to go to the coffee shop, she was able to … travel on a bus.

Participants expressed the challenge of reconciling the tension between (a) being aware of the pitfalls of judging by appearances and (b) being aware that we do judge by appearances:

I think there were a lot of times with the language and the behaviour that were slightly out of sync … [I am] trying to justify myself because I feel a bit uncomfortable I have to say in myself saying that it seemed odd that she was loading the car.

Participants transferred this from the film setting to their own clinical experience:

When she was … putting make-up on … she was trying to justify … that is just part of how we present ourselves; that doesn’t mean she is not in pain. And that is so important to understand I think, because sometimes we say ‘Oh she came in with back pain but I don’t think she’s really in pain’ … But really even if somebody is in pain and distress, it doesn’t always have to be in how they present themselves and I think that came as a huge surprise to me.

I’ve often been surprised if I get them to score their pain … often their scores are very different to what I think they’re going to be … by looking at them you wouldn’t think that they were in pain … They’re not showing that they are in pain, so when they say that they’ve got an 8/10 score it often still surprises me.

The value of seeing the person beyond the performance

Participants discussed the importance of seeing the person beneath the outward performance of pain and understanding their suffering:

That sense of loss of identity; [she was] disconnected from herself. Powerlessness … and that sense of not knowing who she was anymore, and the identity she’d forged … [had] slipped through fingers somehow … it felt [like] a very, very universal sentiment.

It’s almost like bereavement for the life that she had planned out for herself.

I was very struck how her pain seemed to really affect her identity as a person and I don’t think that I had reflected on that in the past … not quite as much.

They discussed how the film effectively performed embodied human experience:

I kind of connected with how she was speaking about … being more about who and how we survived really a lot of the time … So, it was quite powerful.

We have to change our attitude towards these patients … we can see breathlessness, we can see a tumour … we can’t actually see the pain [in the film] but we can feel a sense of their suffering.

Transferring this knowledge to clinical practice, participants discussed the value of not only investigating the body but also asking questions that explore the impact of pain on a person’s life and identity:

So I think … to be asking more searching questions would perhaps give us a clearer idea of exactly what their quality-of-life is and how much pain they’re actually in.

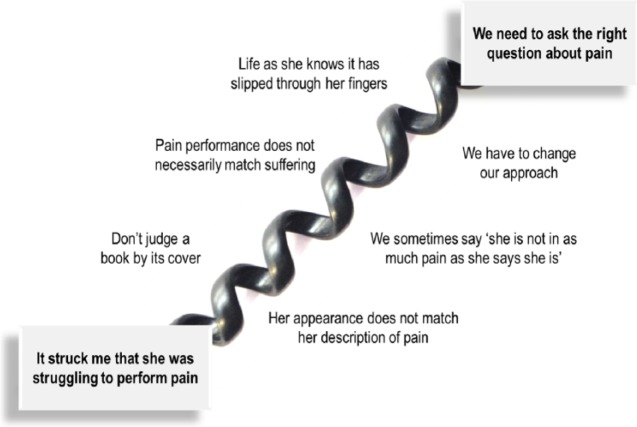

Figure 1 illustrates knowledge mobilisation from the theme ‘Struggling to perform pain’; participants are struck by the performance of pain, they begin to challenge the link between reality and appearance, they question their own clinical practice, they describe a need for change and they contemplate a change of approach which recognises pain as an embodied human experience.

Figure 1.

Illustrating the process of knowledge mobilisation from the theme ‘Struggling to perform pain’.

Participants describe the experience of watching the film as part of a shared dialectic process as opposed to a transfer of facts:

I suppose having a resource that actually makes you think and consider the processing as opposed to more the factual.

This process facilitated change in clinical practice:

I found I probably learnt more, it made me think more about my practice and how I interact with patients than perhaps some of the other resources have.

Discussion

We have described one theme from a systematic qualitative review,2 performed through film, which demonstrates the learning potential of qualitative films in pain education. We aimed to explore the impact of the film ‘Struggling to be me’ on clinician’s understanding of patients’ experience of chronic pain and suggest how this knowledge might be used for improved healthcare for people with pain. All the participants mentioned the potential usefulness of this short film in clinical pain education. Importantly, the film was useful in succinctly demonstrating to clinicians the pitfalls of judging a person’s pain by his or her appearance and allowing them to contemplate the value of seeing the person beyond his or her external appearance of pain.

Qualitative research findings can represent alternative, challenging or unheard, perspectives for reflective consideration. However, the proliferation of qualitative research and the complexity of locating qualitative findings on the research databases increase the danger that qualitative findings are under-valued in education. Frank describes Aristotle’s three genres of knowledge: Episteme (rational/scientific), Techne (practical/goal-driven) and Phronesis or practical wisdom.22 Phronesis underpins clinical practice; it is a ‘performed’ or dialectic form of knowledge which shapes, and is shaped by, our experience. Set in this framework, this study demonstrates that qualitative findings can encourage pain clinicians to reflect on their provision of care. More research is needed to explore the impact of this film on different stakeholders. There are also areas for methodological development in performative approaches to qualitative research.17,18

In summary, qualitative research can make pain clinicians usefully think about the care provided to people with chronic pain. This type of researched film can provide an accessible and succinct medium to present qualitative findings for pain clinicians.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the clinicians who participated in the interviews; the research team who undertook the qualitative synthesis on which the film was based; the team at Red Balloon Productions, Media School, Bournemouth for producing the film and the patients whose voices contributed to the original studies on which the film was based.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, et al. Patients’ experiences of chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain – a qualitative systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2013; 63: 545–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, et al. A meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain. Health Serv Deliv Res 2013; 1: 1–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Greenhalgh T, Wieringa S. Is it time to drop the ‘knowledge translation’ metaphor? A critical literature review. J R Soc Med 2011; 104: 501–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Greenhalgh T. What is this knowledge that we seek to ‘exchange’? Milbank Q 2010; 88: 492–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Forster M. Hegels dialectic method. In: Beiser FC. (ed.) The Cambridge companion to Hegel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993, pp. 130–170. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Polanyi M. The tacit dimension. London: Routledge, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Turner V. The anthropology of performance. New York: PAJ Publications, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gergen M, Jones K. Editorial: a conversation about performative social science. Forum Qual Soc Res 2008; 9 Available at: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0802437 [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCullough M. Bringing drama into medical education. Lancet 2012; 379: 512–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosenbaum ME, Ferguson KJ, Herwaldt LA. In their own words: presenting the patient’s perspective using research-based theatre. Med Educ 2005; 39: 622–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saldana J. Dramatizing data: a primer. Qual Inq 2003; 9: 218–236. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lafreniere D, Cox SM. Performing the human subject: arts-based knowledge dissemination in health research. J Appl Arts Health 2012; 3: 243–257. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rossiter K, Kontos P, Colantonio A, et al. Staging data: theatre as a tool for analysis and knowledge transfer in health research. Soc Sci Med 2008; 66: 130–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Colantonio A, Kontos PC, Gilbert JE, et al. After the crash: research-based theater for knowledge transfer. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2008; 28: 180–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pulman A, Galvin K, Hutchings M, et al. Empathy and Dignity through technology: using lifeworld-led multimedia to enhance learning about the head, heart and hand. Electron J e Learn 2012; 10: 349–359. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Keen S, Todres L. Strategies for disseminating qualitative research findings: three exemplars. Forum Qual Soc Res 2007; 8: Article 7. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fraser KD, al Sayah F. Arts-based methods in health research: a systematic review of the literature. Arts Health 2011; 3: 110–145. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boydell KM, Gladstone BM, Volpe T, et al. The production and dissemination of knowledge: a scoping review of arts-based health research. Forum Qual Soc Res 2012; 13: Article 32. [Google Scholar]

- 19. NVivo. NVivo qualitative data analysis and software. In: Software for qualitative data analysis, 9th edn. Melbourne: QSR International Pty Ltd, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, et al. ‘Trying to pin down jelly’ – exploring intuitive processes in quality assessment for meta-ethnography. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013; 13: 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Frank A. Asking the right question about pain: narrative and phronesis. Lit Med 2004; 23: 209–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]