Abstract

Background

Oxidative stress is manifested in embryos exposed to maternal diabetes, yet specific mechanisms for diabetes-induced heart defects are not defined. Gene deletion of intermediates of Wingless-related integration (Wnt) signaling causes heart defects similar to those observed in embryos from diabetic pregnancies. We tested the hypothesis that diabetes-induced oxidative stress impairs Wnt signaling thereby causing heart defects, and that these defects can be rescued by transgenic overexpression of the reactive oxygen species scavenger SOD1.

Methods and Results

Wild-type (WT) and superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) overexpressing embryos from nondiabetic WT control dams and nondiabetic/diabetic WT female mice mated with SOD1 transgenic male mice were analyzed. No heart defects were observed in WT and SOD1 embryos under nondiabetic conditions. WT embryos of diabetic dams had a 26% incidence of cardiac outlet defects that were suppressed by SOD1 overexpression. Insulin treatment reduced blood glucose levels and heart defects. Diabetes increased superoxide production, canonical Wnt antagonist expression, caspase activation, and apoptosis, and suppressed cell proliferation. Diabetes suppressed Wnt signaling intermediates and Wnt target gene expression in the embryonic heart, each of which were reversed by SOD1 overexpression. Hydrogen peroxide and peroxynitrite mimicked the inhibitory effect of high glucose on Wnt signaling, which was abolished by the SOD1 mimetic, tempol.

Conclusions

The oxidative stress of diabetes impairs Wnt signaling and causes cardiac outlet defects that are rescued by SOD1 overexpression. This suggests that targeting of components of the Wnt5a signaling pathway may be a viable strategy for suppression of CHDs in fetuses of diabetic pregnancies.

Keywords: heart defects, congenital, heart development, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, maternal diabetes, oxidative stress, Wnt signaling

Congenital heart defects (CHD) are the most prevalent birth defects occurring in approximately 4–10 per 1000 live births1. To date, there are major breakthroughs in understanding the genetic basis of CHD. However, ample epidemiological evidences suggest a significant contribution of environmental factors to the induction of CHD2–4. Unfortunately, there is relatively less mechanistic information about the non-genetic factors that adversely affect heart development. Pregestational maternal diabetes is a non-genetic factor that is associated with a five-fold increase in CHD risk3, 4. The CHD commonly seen in diabetic pregnancies are ventricular septal defects (VSD)3, 5 and outflow tract defects3, 4. The same types of CHD also are observed in diabetic animal models6, 7. Studies of animal models have suggested that apoptosis8–10 and gene dysregulation6, 10, 11 are involved in diabetes-induced CHD. However, the mechanism underlying defective heart formation under diabetic conditions is not clearly defined.

Wnt signaling is essential for normal heart development12. Targeted gene deletion of key Wnt intermediates results in heart defects similar to those observed in human diabetic pregnancies13, 14. Altered Wnt signaling has been implicated in diabetes-induced birth defects15. However, the role of the Wnt pathway in diabetes-induced heart maldevelopment has not been clarified. Wnt signaling has traditionally been classified into the canonical and the non-canonical pathways12. In the canonical pathway, Wnt ligands bind to the membrane-spanning receptor proteins, Frizzleds, and subsequently trigger the phosphorylation of Dishvelled protein (Dvl). Dvl activates a signaling cascade that results in the stabilization and nuclear localization of β-catenin, which interacts with the T cell-specific factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (TCF/LEF) transcription factor to induce the transcription of canonical Wnt signaling target genes. In the absence of Wnt proteins, β-catenin is phosphorylated by glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK3β) and degraded through the ubiquitin-proteosome pathway. The non-canonical Wnt ligand, Wnt5a, activates the Ca2+/calcineurin signaling pathway, which is critically involved in cardiogenesis16. Wnt5a activates calcineurin and its downstream transcriptional effector, the nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT)16. In the nucleus, NFAT is associated with transcription factors such as activator protein 1 (AP-1) and myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) to induce gene transcription17. The Ca2+/calcineurin/NFAT signaling pathway is essential for outflow track development, normal cardiac valve and septum morphogenesis16–18.

Maternal diabetes increases the production of reactive oxygen species and impairs endogenous antioxidant activities leading to oxidative stress during embryonic organogenesis19, 20. Antioxidant treatments elicit some beneficial effects against hyperglycemia-induced CHD9, 21. In addition, inducing oxidative stress by an inhibitor of the mitochondrial respiratory chain replicates the effect of maternal diabetes on CHD formation9. These studies implicate a critical role of oxidative stress in maternal diabetes-induced CHD. To unravel the molecular pathway downstream of oxidative stress leading to CHD in diabetic pregnancies is an essential step towards the development of effective interventions, which directly target identified molecular intermediates downstream of oxidative stress. Our previous studies showed that superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) overexpression in SOD1 transgenic (SOD1-Tg) mice abrogates maternal diabetes-induced oxidative stress22–24. Using the SOD1-Tg mouse model, we aimed to determine whether oxidative stress is responsible for CHD formation under maternal diabetic conditions and whether maternal diabetes alters Wnt signaling in the developing heart.

Methods

Mouse models of diabetic embryopathy

Mouse models of maternal diabetes-induced embryonic malformations were described previously25, 26. The procedures for animal use were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Statistical analyses

Data on heart defect rates were analyzed by Fisher’s Exact test or Chi square test. Data on protein and mRNA expression are presented as means ± standard errors (SE). The non-parametric Mann Whitney test was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics software to estimate significance. Statistical significance was accepted when P < 0.05 in multiple comparisons.

Results

SOD1 overexpression suppresses maternal diabetes-induced oxidative stress in the developing heart

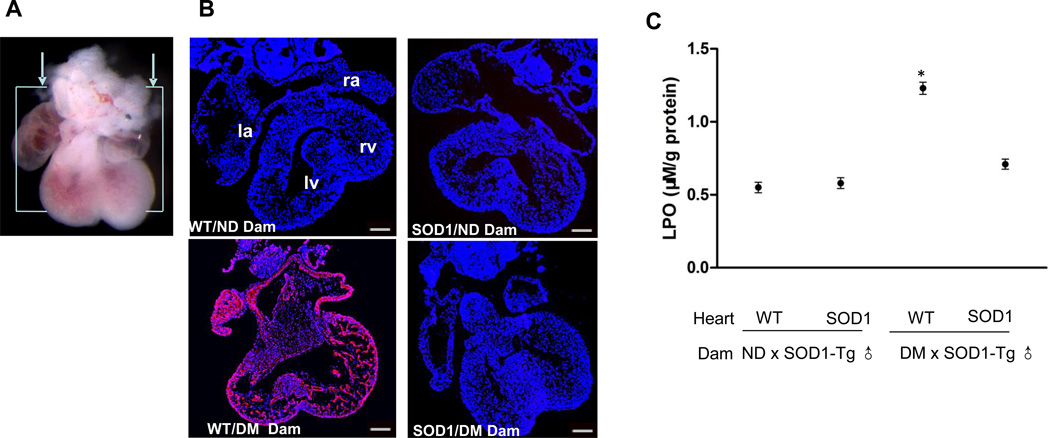

Staining with DHE of sections in a frontal plane with respect to the heart as shown in Fig. 1A was used to detect superoxide in the embryonic heart. E12.5 hearts from nondiabetic dams showed minimal fluorescent signal whereas embryonic hearts from diabetic mice exhibited robust DHE staining (Figure 1B). Maternal diabetes also significantly increased the abundance of lipid hydroperoxide, an index of lipidperoxidation, in the developing heart (Figure 1C). SOD1 overexpression suppressed maternal diabetes-increased DHE staining (Figure 1B) and lipidperoxidation (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

SOD1 overexpression abrogates maternal diabetes-induced oxidative stress in the developing heart. A. E12.5 hearts were sectioned in a frontal plane as shown. B, representative images of DHE staining in E12.5 heart sections. DHE reacts with cellular superoxide producing red fluorescence product 2-hydroxyethidium. All cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (Blue). Three hearts from embryos of three different dams (n = 3) per group were used and similar results were obtained. Bars = 150 µm. C, levels of lipid hydroperoxide (LPO) in E12.5 hearts, expressed as µM per gram of protein. Hearts from embryos of five different dams (n = 5) per group were analyzed. * indicates significant differences compared to the other three groups. ND: nondiabetic; DM: diabetic mellitus; WT: wild-type hearts; SOD1: SOD1 overexpressing hearts.

Suppression of oxidative stress reduces the frequency of maternal diabetes-induced heart defects

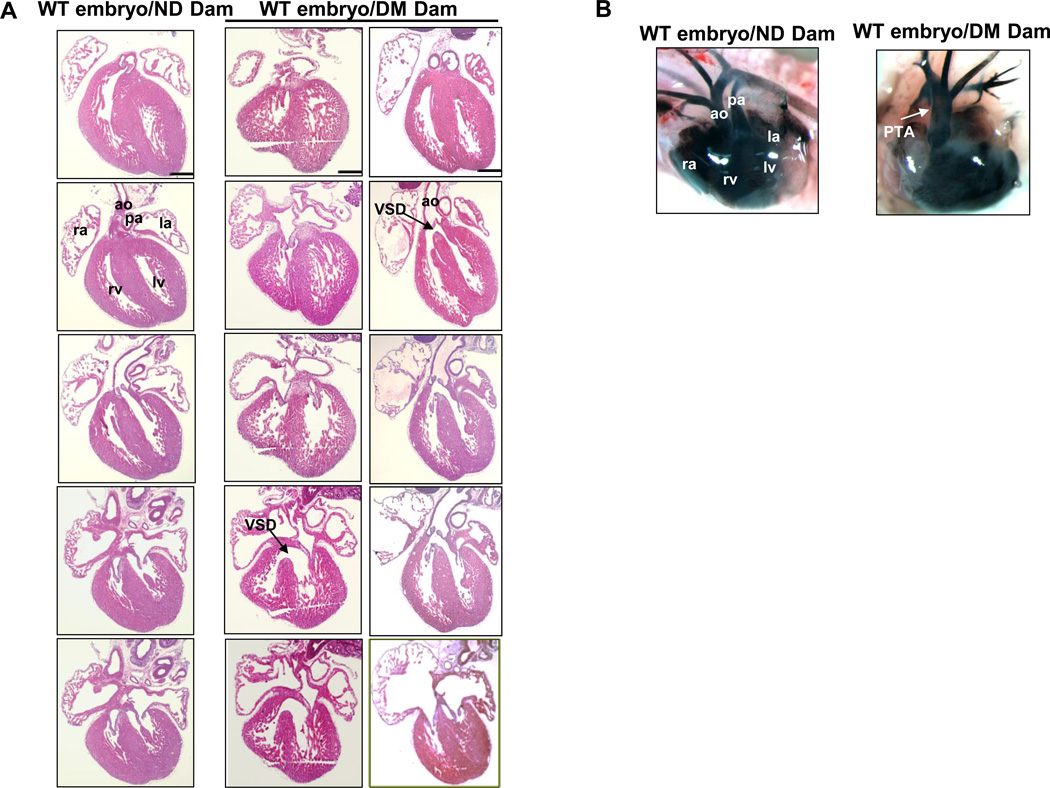

Maternal diabetes significantly induced heart defects. Embryos from diabetic dams did not appear to be growth retarded as determined by somite numbers. Serial cross sections of E17.5 hearts in embryos exposed to diabetes revealed large VSDs in 18% of hearts (Table 1 and Figure 2A). The VSDs in anterior positions (Figure 2A) were in the cardiac outlet and associated with an over-riding aorta (Figure 2A). More posterior VSDs were large and in the muscular septum. Indian ink injections indentified PTA in four of 50 embryos exposed to diabetes (Table 1, Figure 2B). We next examined the incidence of heart defects in wild-type and SOD1 overexpressing embryos from wild-type dams mated with wild-type or SOD1 transgenic males. Under nondiabetic conditions, SOD1 overexpression did not affect heart development (Table 1). The incidence of heart defects in wild-type embryos (n=50) from diabetic wild-type dams mated with wild-type males was 26% (Table 1). The types of heart defects were VSDs with or without aorta over-riding (Figure 2A) and PTAs (Figure 2B). Likewise, a similar high incidence of heart defects was also present in wild-type embryos from diabetic wild-type dams mated with SOD1-Tg male mice (Table 1, Figure 2B). In contrast, there were no heart defects in SOD1 overexpressing embryos from diabetic wild-type dams mated with SOD1-Tg male mice (Table 1). To reveal whether reduced hyperglycemia by insulin treatment ameliorates diabetes-induced heart defects, insulin pellets remained in diabetic dams throughout the course of the experiments. Insulin treatment effectively reduced blood glucose levels in diabetic dams and significantly reduced the incidence of heart defects (Table 1). These results support our hypothesis that hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress mediates the teratogenic effect of maternal diabetes on the developing heart.

Table 1.

Heart Defect Rates in E17.5 embryos of nondiabetic and diabetic dams

| Experimental | group | Glucose level(mg/dl) |

Embryo Genotype |

Total embryos |

Total heart defect embryos |

Embryos with specific heart defects |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSD | VSD with AO | PTA | ||||||

| ND | WT ♂ × WT ♀ (8 litters) | 140.8±9.3 | WT | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| SOD1-Tg ♂ × WT ♀ (14 litters) | 124.8±12.6 | WT | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SOD1 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| DM | WT ♂ × WT ♀ (9 litters) | 433.8±20.6 | WT | 50 | 13 (26%)* | 6 | 3 | 4 |

| SOD1-Tg ♂ × WT ♀ (14 litters) | 443.6±14.7 | WT | 40 | 10 (25%)* | 5 | 2 | 3 | |

| SOD1 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| DM+Insulin | SOD1-Tg ♂ × WT ♀ (9 litters) | 250.9±26.9 | WT | 31 | 2 (6.0%)† | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| SOD1 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

ND: nondiabetic; DM: diabetes Mellitus; DM+Insulin: insulin pellets were maintained throughout the course of experiments. WT: wild-type; Tg: Transgenic; ♂: male and ♀: female (dams); VSD: ventricular septal defects; AO: aorta over-riding; PTA: persistent truncus arteriosus.

indicate significant difference compared with SOD1 overexpressing embryos and embryos in the ND group.

depict significant difference compared with WT embryos from WT males and WT DM dams.

Figure 2.

Maternal diabetes induces outflow tract and ventricular septal defects (VSDs). A), H&E stained of E17.5 hearts from anterior to posterior: normal heart (left column) from WT embryos of nondiabetic (ND) dam, heart with an isolated VSD (middle column) representative images of hematoxylin and eoxin-stained sections whereas B were representative images of india ink dye injections in E17.5 embryonic hearts. A represented morphologically normal heart (left column) from WT embryos of nondiabetic (ND) dam, a typical VSD heart (middle column) and aorta-overriding VSD heart (right column) from WT embryos of diabetic (DM) dam; B, E17.5 heart and blood vessels imaged in whole mount after injection of India Ink: a normal heart from WT embryos of nondiabetic dam and a heart with PTA from WT embryos of diabetic dam. Scale bars = 300 µm. AO: Aorta; PA: Pulmonary Artery; LA: Left Atrium; RA: Right Atrium; LV: left ventricle; RV: right ventricle; VSD: Ventricular septum defect; PTA: Persistent truncus arterious.

SOD1 overexpression inhibits caspase activation and apoptosis, and restores cell proliferation in the developing heart exposed to diabetes

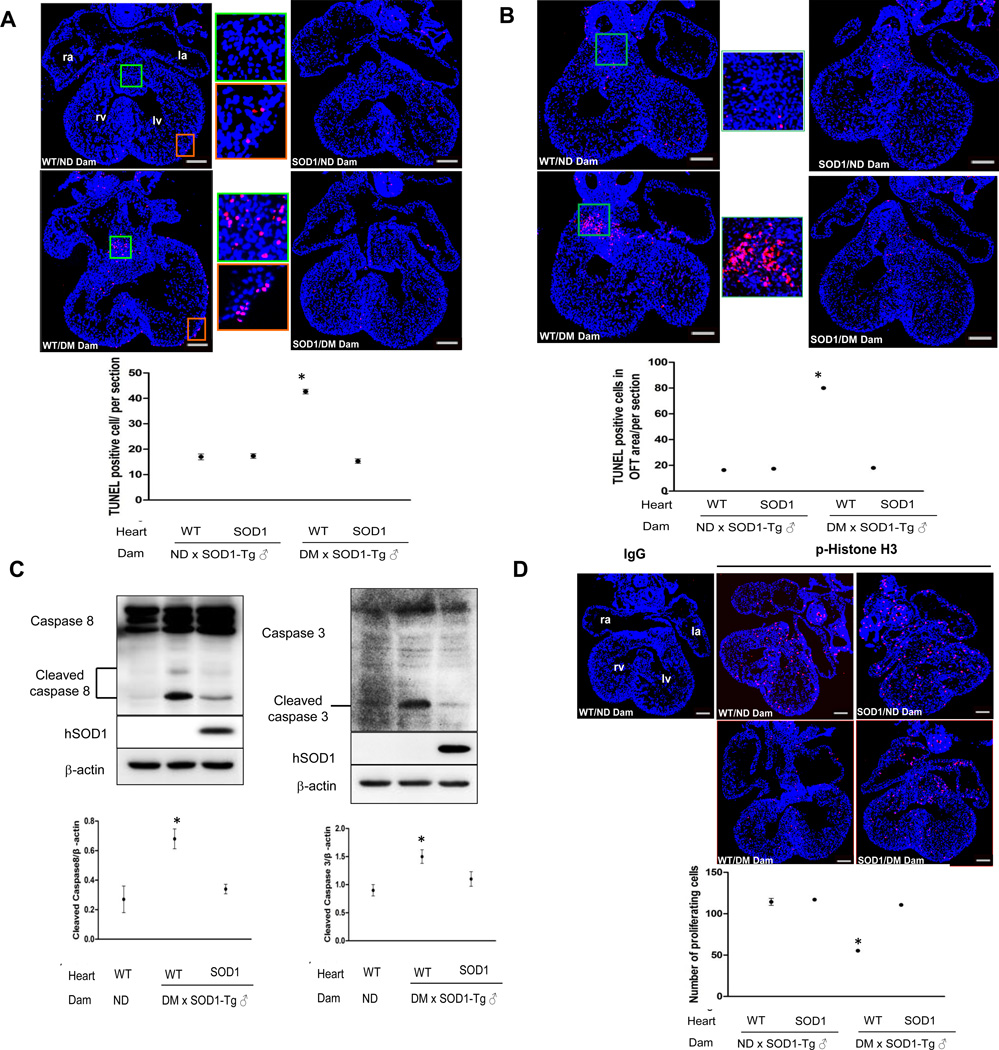

Previous studies have reported that maternal diabetes induces apoptosis in cells of the developing heart8–10. We sought to determine whether oxidative stress is responsible for diabetes-induced apoptosis. By TUNEL assay, apoptotic cells were present with increased frequency in the endocardial cushions of the OFT and AV canal and the epicardial lining of the ventricles of E12.5 wild-type embryos from diabetic dams (Figure 3A, B). Under diabetic conditions, SOD1 overexpressing hearts had significantly fewer apoptotic cells compared to wild-type hearts (Figure 3A, B). Maternal diabetes induces apoptosis in a caspase dependent manner in neurulation stage embryos24, 25. To determine whether maternal diabetes induces caspase activation in the heart, cleaved caspase 3 and caspase 8 were assessed. Maternal diabetes induced caspase 3 and caspase 8 cleavage in wild-type embryos but cleaved caspase products were significantly reduced in SOD1 overexpressing embryos (Figure 3C). We used p-Histone H3 staining to evaluate cell proliferation. Maternal diabetes significantly reduced the number of cells with p-Histone H3 staining and SOD1 overexpression blunted the reduction in the number of p-Histone H3 positive cells (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

SOD1 overexpression suppresses maternal diabetes-induced cell apoptosis and caspase activation and normalizes cell proliferation in the developing heart. A and B, representative images of the TUNEL assay showing apoptotic cells (Red signal) and quantified as TUNEL positive cells per section (3 sections from 3 different hearts of each group). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (Blue). TUNEL positive cells in the A-V and outflow tract endocardial cushion are shown in A and B, respectively. In A, TUNEL positive cells are also seen in the epicardium lining the ventricle. Bars = 150 µm. C, representative western blot for detection of cleaved caspase 3, 8 and the quantification normalized to β-actin. Human SOD1 (hSOD1), the transgene product, was detected by a specific human SOD1 antibody. Experiments were repeated three times using hearts from embryos of three different dams (n = 3) per group. D, representative images of p-Histone H3 immunostaining, which labels proliferating cells. p-Histone H3 positive cells are labeled by red signal and cell nuclei are stained by DAPI (Blue). In the dot graph, p-Histone H3 positive cells were quantified by the NIH Image J software and expressed as number of cells per section. Three hearts from embryos of three dams (n = 3) per group, and three serial sections per heart were analyzed. Bars = 150 µm. IgG: normal rabbit IgG controls; WT: Wild-type; ND: nondiabetic; DM: diabetic mellitus. * indicates significant difference compared to other groups.

SOD1 overexpression blocks the inhibitory effect of maternal diabetes on canonical Wnt signaling in the developing heart

We analyzed the mRNA expression of five canonical Wnt ligands--Wnt1, Wnt2a, Wnt3a, Wnt7b and Wnt8a--and observed no significant changes in hearts from wild-type embryos or SOD1 overexpressing embryos under both nondiabetic and diabetic conditions (data not shown). Because SOD1 overexpression under nondiabetic conditions does not affect heart development, cell apoptosis and proliferation, subsequent analyses will not include this group.

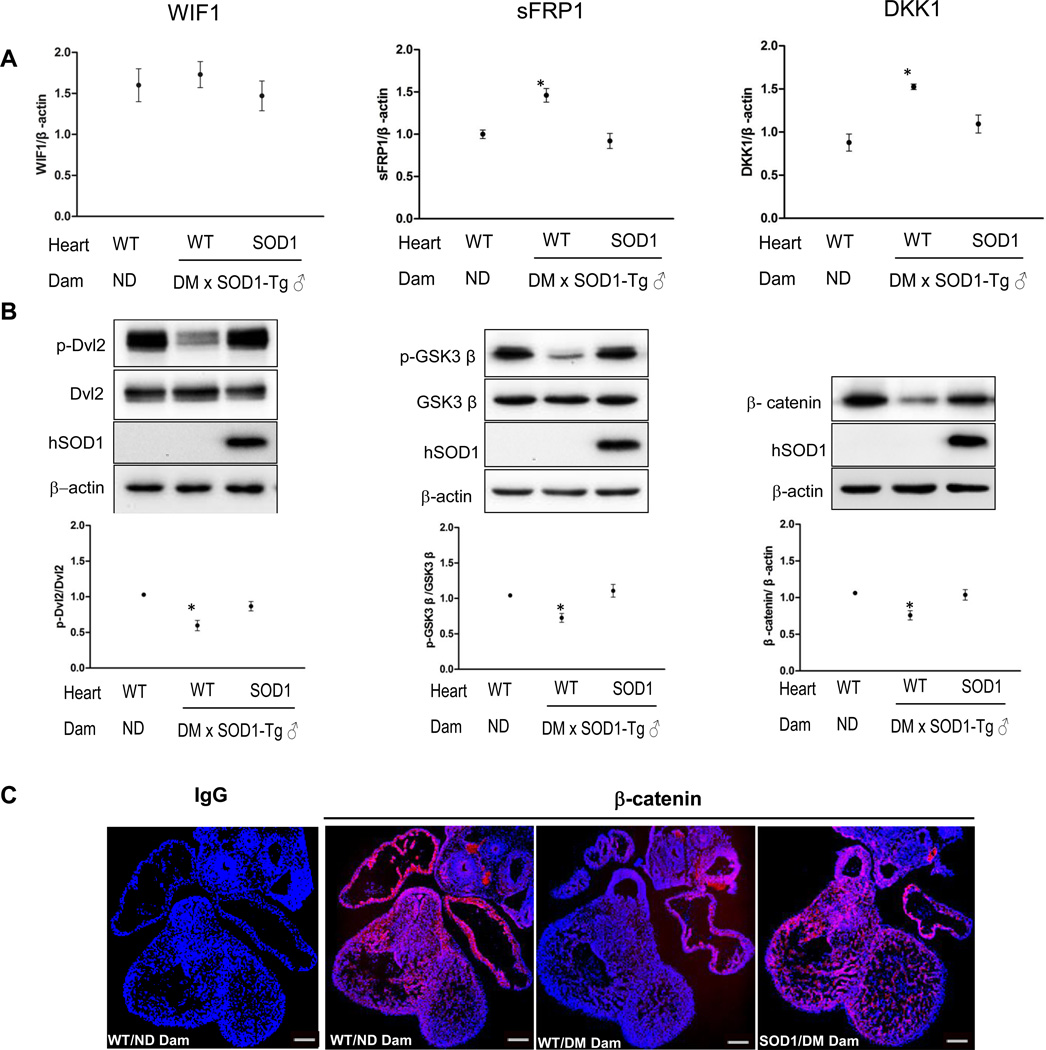

Because Wnt expression at the mRNA level is not changed, we turned our attention to factors that may block Wnt protein binding. The availability of Wnt ligands for their receptors is regulated by secreted Wnt antagonists. The mRNA expression of three major Wnt antagonists was assessed. The mRNA expression of the Wnt antagonist, WIF1, was not affected by maternal diabetes (Figure 4A). However, the mRNA expression of the other two Wnt antagonists, sFRP1 and DKK1, was significantly increased in hearts of wild-type embryos from diabetic dams compared to those in hearts of wild-type embryos of nondiabetic dams and SOD1 overexpressing embryos of diabetic dams (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

SOD1 overexpression rescues diabetes-increased canonical Wnt antagonists and restores the expression of key canonical Wnt intermediates. A, mRNA abundance of the three canonical Wnt antagonists. B, representative western blots of phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated Dvl2, p-GSK3β and β-catenin. The dot graphs showed the quantification of the immunoblotting. In A and B, three hearts from embryos of three dams (n = 3) per group were analyzed. C, images of β-catenin immunostaining. Rabbit normal IgG served as controls. Red signal was β-catenin and cell nuclei were stained by DAPI (Blue). Three E12.5 hearts from embryos of three dams (n = 3) per group, and three serial sections per heart were analyzed, and similar results were obtained. Bars = 150 µm. * in A, B indicate significant difference compared to other groups. ND: nondiabetic; DM: diabetic mellitus; WT: wild-type hearts; SOD1: SOD1 overexpressing hearts.

To determine whether diabetes-induced increases in sFRP1 and DKK1 expression impact canonical Wnt signaling, we analyzed the phosphorylation status of key canonical Wnt signaling intermediates. Consistent with the increase of Wnt antagonists, maternal diabetes significantly decreased Dvl2 phosphorylation, a positive canonical Wnt signaling transducer, and increased GSK3β activity by reducing the levels of phosphorylated GSK3β (an inactive form of GSK3β), a negative canonical Wnt signaling regulator (Figure 4B). SOD1 overepxression blunted maternal diabetes-induced Dvl2 dephosphorylation and GSK3β phosphorylation (Figure 4B). All the above upstream Wnt signaling components eventually converge on β-catenin, the central mediator of the canonical Wnt pathway. Total β-catenin protein abundance was decreased by diabetes and SOD1 overexpression blocked this effect (Figure 4B). Under nondiabetic conditions, β-catenin was robustly present in the ventricular myocardium, the endocardial cushion and outflow tract (Figure 4C). Maternal diabetes suppressed β-catenin protein staining in the ventricular myocardium, the endocardial cushion, and the outflow tract area (Figure 4C). These results suggest that maternal diabetes blocked the canonical Wnt signaling in the developing heart. Under diabetic conditions, SOD1 overexpression restored β-catenin expression in the heart (Figure 4C).

SOD1 overexpression restores maternal diabetes-impaired non-canonical Wnt signaling in the developing heart

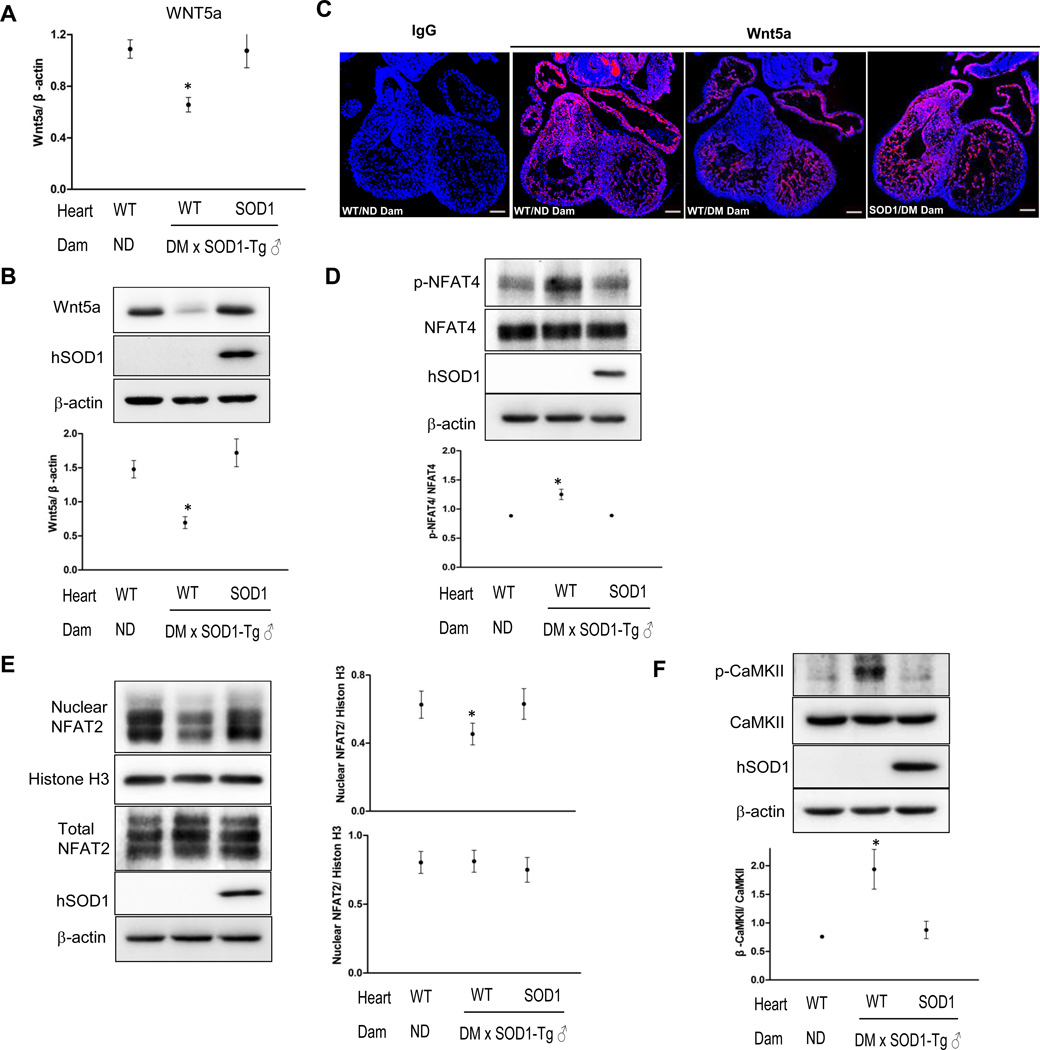

We next investigated whether the non-canonical Wnt signaling also is affected by maternal diabetes. Abundance of the major non-canonical Wnt ligand, Wnt5a mRNA and protein, was significantly decreased in hearts of wild-type embryos of diabetic dams compared with those in hearts of wild-type embryos from nondiabetic dams and SOD1 overexpressing embryos from diabetic dams (Figure 5A). Immunofluorescent staining revealed that Wnt5a was predominately localized in the cardiac outflow tract (Figure 5C). Maternal diabetes suppressed and SOD1 overexpression restored Wnt5a expression in the outflow tract area (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Maternal diabetes impairs the non-canonical Wnt pathway and this impairment is abolished by SOD1 overexpression. A, mRNA levels of Wnt5a in E12.5 hearts. B, Wnt5a protein levels in E12.5 hearts. C, images of Wnt5a immunostaining. Rabbit normal IgG served as controls. Red signal was Wnt5a and cell nuclei were stained by DAPI (Blue). Three hearts from embryos of three dams (n = 3) per group, and three serial sections per heart were analyzed, and similar results were obtained. Bars = 150 µm. D, levels of p-NFAT4. E, levels of nuclear NFAT2. F, levels of p-CaMKII. In B, D, E, and F, quantification of immunoblotting was shown in the dot graph. In A, B, D, E, F, experiments were repeated three times using three E12.5 hearts from embryos of three dams (n = 3) per group. * in A, B, D, E, F indicate significant difference compared to other groups. ND: nondiabetic; DM: diabetic mellitus; WT: wild-type hearts; SOD1: SOD1 overexpressing hearts.

Wnt5a is essential for normal cardiac outflow tract development and deletion of Wnt5a gene induces cardiac outflow tract defects16 similar to those observed in diabetic pregnancies. Wnt5a binds to the receptor tyrosine kinase Ror1/2 leading to activation of the non-canonical Ca2+/ NFAT pathway27. NFAT2 and NFAT4 are two members of the NFAT family that are critical for cardiogenesis17, 18. The level of phosphorylated NFAT4 (inactive form) was significantly upregulated by maternal diabetes (Figure 5D). Maternal diabetes-induced NFAT4 phosphorylation was diminished by SOD1 overexpression. NFAT2 protein abundance in nuclear fractions was significantly decreased by maternal diabetes and SOD1 overexpression restored NFAT2 nuclear accumulation (Figure 5E). On the other hand, levels of the phosphorylated (active) CaMKII, a negative regulator of the non-canonical Ca2+/ NFAT pathway28, were significantly increased by maternal diabetes (Figure 5F) and this increase was blunted by SOD1 overexpression (Figure 5F). These results support that oxidative stress is responsible for maternal diabetes-induced impairment of the non-canonical Wnt5a- Ca2+/ NFAT pathway.

SOD1 overexpression restores maternal diabetes-suppressed Wnt target gene expression in the developing heart

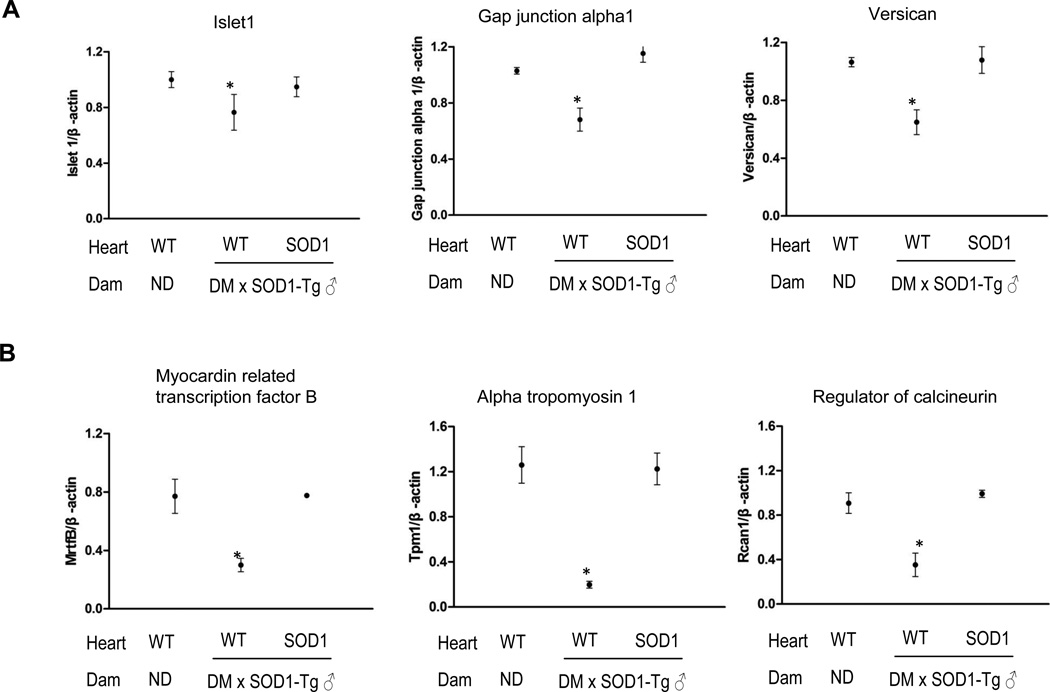

Because maternal diabetes suppresses the canonical Wnt signaling, we tested three target genes of the canonical Wnt signaling, Islet1, GJA1 and Versican. The mRNA levels of these three genes were significantly decreased by maternal diabetes (Figure 6A) and restored by SOD1 overexpression (Figure 6A). Similarly, the mRNA levels of three NFAT target genes (Mrtf-b, Tpm1 and Rcan1) were significantly lower in hearts of wild-type embryos exposed to diabetes that those in hearts of wild-type embryos from nondiabetic dams (Figure 6B). SOD1 overexpression restored the expression of Mrtf-b, Tpm1 and Rcan1 that was suppressed by maternal diabetes (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

SOD1 overexpression rescues maternal diabetes-reduced Wnt target gene expression. A, mRNA levels of canonical Wnt target genes. B, mRNA levels of noncanonical Wnt targe genes. ND: nondiabetic; DM: diabetic mellitus; WT: wild-type hearts; SOD1: SOD1 overexpressing hearts. Five hearts from E12.5 embryos of five dams (n = 5) per group were analyzed. * indicate significant difference compared to other groups.

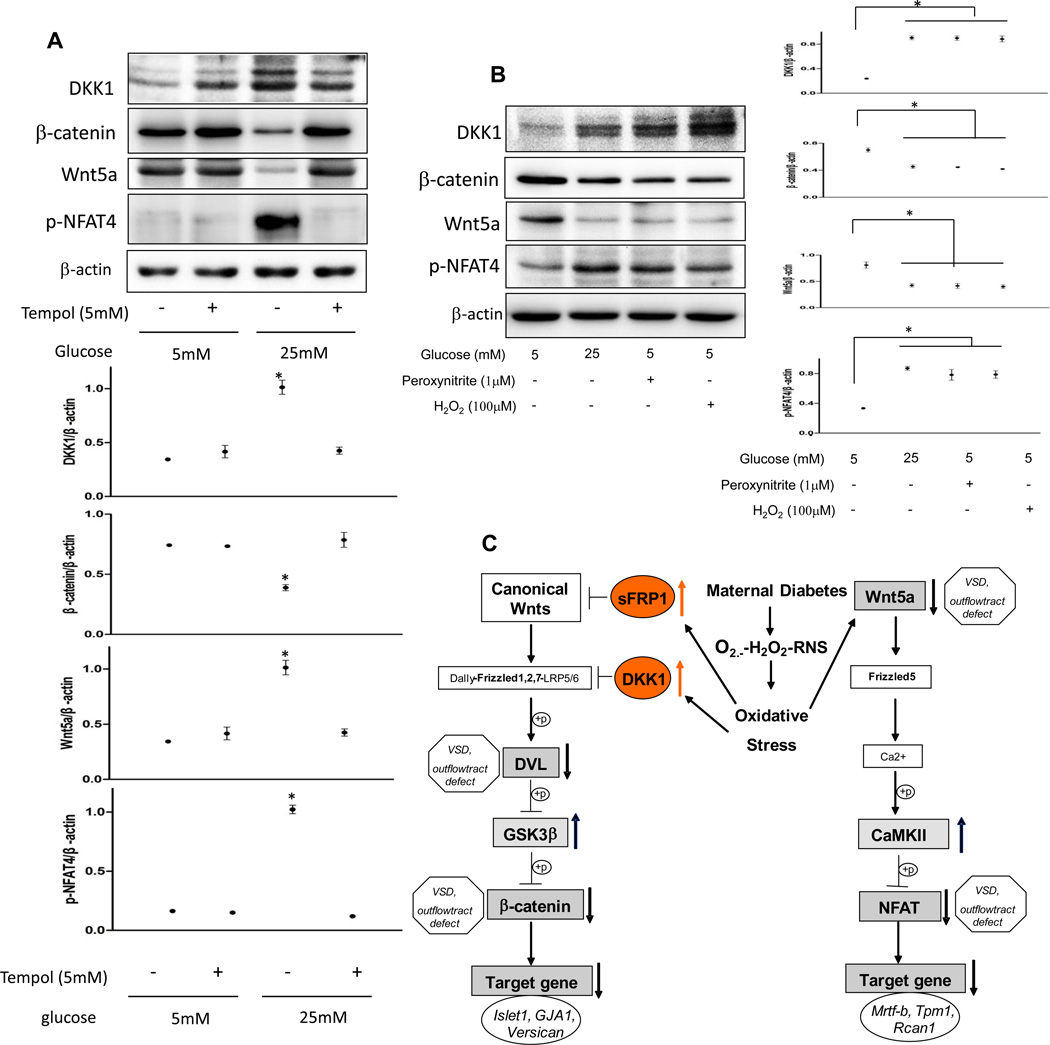

Both hydrogen peroxide and peroxynitrite mimic the inhibitory effect of high glucose on Wnt signaling

Next, we sought to determine if ROS or RNS suppression of Wnt signaling directly mediates the teratogenic effect of maternal diabetes on the developing heart by exposing cultured embryos to these agents in vitro. Treatment with either 100 µM H2O2 or 1 µM peroxynitrite mimicked high glucose-suppression of β-cetenin and Wnt5a expression, increased DKK1 expression, and inactivated the key non-canonical intermediate, NFAT4, through phosphorylation (Fig. 7B). The ROS scavenger (SOD-mimetic) Tempol (5 mM) restored high glucose-inhibited canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling (Fig. 7A). Thus SOD1 overexpression in vivo and tempol treatment in vitro abrogated Wnt signaling inhibition by diabetes or high glucose, supporting ROS inhibition of Wnt signaling playing a causal role in diabetes induced heart defects.

Figure 7.

The SOD1 mimetic, tempol, abolishes high glucose-suppressed Wnt signaling, and both ROS and RNS inhibit Wnt signaling in cultured hearts. A and B, DKK1, β-catenin, Wnt5a and phosphorylated NFAT4 levels in cultured hearts. Experiments were repeated three times. * indicate significant difference compared with other groups.. C. Schematic of oxidative stress-mediated Wnt signaling impairment in the developing heart leading to heart defects under maternal diabetic conditions. Oxidative stress induced by maternal diabetes inhibits both the canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling pathways through two distinct mechanisms. Maternal diabetes suppresses the canonical Wnt signaling by increasing its antagonist expression and the activity of its negative regulator whereas it inhibits the non-canonical Wnt signaling by downregulating Wnt5a.Major types of heart defects associated with gene deletion of key Wnt intermediates are indicated. p means phosphorylation.

SOD1 overexpression is unable to prevent heart defects in Wnt5a null embryos

Because SOD1 overexpression restored the non-canonical Wnt signaling by both preventing Wnt5 down-regulation and inactivating the negative regulator, CaMKII, it is possible that SOD1 may act downstream of Wnt5a. To test whether SOD1 rescues the non-canonical Wnt signaling by directly inhibiting negative regulators downstream of Wnt5a, Wnt5a+/− females were crossed with Wnt5a+/−;SOD1 males to generate Wnt5a null embryos with or without SOD1 overexpression (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 1). As previously reported16, Wnt5a null embryos exhibited heart defects (VSD and PTA) with 100% penetrance similar to those in embryos of diabetic dams (Supplementary Table 1). SOD1 overexpression did not reduce the incidence of heart defects in Wnt5a null embryos (Supplementary Table 1), suggesting that the heart defects in the Wnt5a knock-out model are not ROS-mediated. These findings support the hypothesis that the beneficial effect of SOD1 is due to its direct effect on Wnt5a by preventing Wnt5a down-regulation.

Discussion

In the current study, we demonstrate that a mouse model of maternal diabetes induces a spectrum of heart defects similar to that of human diabetic pregnancies3, 5. In humans, maternal diabetes induces about 5% VSDs and 12% outflow tract defects3. These incidences are comparable to the incidences of our STZ-induced diabetic mouse model. The heart defect incidences also are in agreement with those of other animal studies6, 7. The cause of these heart defects under maternal diabetic conditions is not clear. Although it has been shown that oxidative stress mimics the teratogenicity of maternal diabetes leading to heart defects9, no direct evidence support the hypothesis that oxidative stress causes heart defects in diabetic pregnancies. Our study demonstrates the presence of superoxide and lipidperoxidation in the developing heart exposed to diabetes. Furthermore, we provide direct evidence supporting the oxidative stress hypothesis by showing that SOD1 overexpression, which effectively mitigates maternal diabetes-induced oxidative stress in the developing heart, prevents diabetes-induced heart defects. Additionally, our ex vivo studies demonstrated that superoxide, hydrogen peroxide and peroxynitrite form a hierarchy of oxidants and are all necessary for the suppression of the Wnt signaling. The SOD1 mimetic, tempol, effectively prevents high glucose-induced impairment of Wnt signaling. In agreement with our findings, a recent study demonstrated that the antioxidant, N-acetylcysteine, suppresses diabetes-induced heart defects29. Our findings advance the oxidative stress hypothesis by revealing perturbed Wnt signaling as a mediator of oxidative stress-induced heart defects. Future studies are needed to identify specific cellular superoxide sources mediating impairment of Wnt signaling in the developing heart. NADPH oxidases and mitochondrial dysfunction are potential sources of cellular ROS and subsequent formation of RNS.

Embryonic heart development is an intricate process that requires fine-tuned cell proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation. Excess apoptosis and reduced cell proliferation have been implicated in CHD formation and myocardial hypoplasia30–33. Enhanced apoptosis8–10 and reduced cell proliferation34 are observed in embryonic hearts exposed to diabetes. The apoptotic cells are present in the endocardial cushion and the myocardium, which may contribute to VSD induction30, and in the outflow tract, which may be responsible for PTA formation. The mechanism underlying maternal diabetes-induced embryonic heart cell apoptosis is elusive. In neurulation stage embryos, caspase 3 and 8 activation are critically involved24, 25, 35. Caspase 8 is an initiator caspase whereas caspase 3 is an executive caspase. Both caspase 3 and 8 are activated in the embryonic heart by maternal diabetes and this activation is blocked by SOD1 overexpression. Oxidative stress can induce caspase activation and subsequent apoptosis by either suppressing pro-survival signaling26, or activating pro-apoptotic signaling26 or both. The Wnt pathway triggers pro-survival signaling and promotes cell proliferation by stimulating cell cycle gene expression35,36. Maternal diabetes inhibits heart cell proliferation and SOD1 abrogates this inhibition. Although other signaling pathway may also be involved, based on our results, it appears that impaired Wnt signaling mainly mediates the promoting effect of apoptosis and the inhibitory effect of cell proliferation downstream of oxidative stress in diabetes-induced CHD.

Maternal diabetes alters signaling pathways such as the BMP4 pathway10 that is essential for normal cardiogenesis. Beyond Wnt inhibition, sFRP1 antagonizes the BMP4 signaling37. It is possible that elevated sFRP1 expression is responsible for maternal diabetes-impaired BMP4 signaling. Both the canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling pathways are crucial for heart development37. In the canonical Wnt pathway, Wnts bind to the Frizzled receptors and trigger Dvl2 activation, which results in the inhibition of GSK3β activity and the subsequent stabilization of its target β-catenin, which leads to gene transcription. Gene deletion of key intermediates in the canonical pathways including Dvl2 and β-catenin causes outflow tract defects including plumonary atresia, PTA and VSD14, 38, which are observed in diabetic pregnancies, suggesting a link between impaired canonical Wnt signaling and maternal diabetes-induced heart defects. Maternal diabetes does not affect the expression of traditionally canonical Wnt members but increases the expression of secreted Wnt antagonists DKK1 and sFRP1. The impact of increased Wnt antagonists is translated into decreased Dvl2 phosphorylation, increased GSK3β activation and destabilizing β-catenin. Deletion of β-catenin results in the loss of cardiac neural crest cells38. Because it has been demonstrated that maternal diabetes induces the loss of cardiac neural crest cells9, we reason that decreased β-catenin may contribute to the loss of these cells leading to outflow tract defects. β-catenin null mutations reduce cell proliferation in the myocardium38. Correlated with outflow tract defects and VSDs in diabetic pregnancies, β-catenin is expressed in the outflow tract area and in the myocardium. Therefore, impaired canonical Wnt signaling may contribute to outflow tract defects and VSD formation.

DKK1 and sFRP1 expression is known to be responsive to oxidative stress39, 40. Our data support that maternal diabetes increases the expression of DKK1 and sFRP1 through oxidative stress. Because the stress kinases, c-Jun-N-terminal kinases 1/2 (JNK1/2), is responsible for the induction of DKK1 by oxidative stress in vitro39, maternal diabetes-induced oxidative stress may stimulate Wnt antagonist expression through JNK1/2, which is activated in embryos exposed to maternal diabetes26. Other stress kinase such as the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway is also activated by maternal diabetes and is downstream of oxidative stress22 and could also play a role in impaired Wnt activation in our mouse model. Epigenetic modifications may be also involved in diabetes-induced sFRP1 and DKK1 expression because studies have suggested that epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation and histone modifications mediate the dysregulated expression of these genes41, 42. The mechanism underlying maternal diabetes-induced Wnt antagonist expression warrants further investigation. The major types of VSDs in our diabetic pregnancy models are peri-membranous VSDs, which likely reflect defects in endocardial cushion development. The defective endocardial cushion development is manifested by enhanced ROS production and apoptosis, and diminished β-catenin expression upon exposure to diabetes. Deletion of the central canonical Wnt mediators, Frizzled 213 and β-catenin38, 43, results in VSDs along with outflow tract defects, implicating that impaired canonical Wnt signaling due to diabetes exposure may be responsible for VSD formation. In these Wnt mutants, both increased apoptosis and decreased cell proliferation likely contribute to the failed closure of the ventricular septum38. The affected cell types include the neural crest cells and cardiomyocytes38. In our model, impaired canonical Wnt signaling may enhance apoptosis and reduce proliferation in cells of endocardial cushion leading to VSD formation. The impaired Wnt signaling may also translate to decreased gene expression that is essential for ventricular septum closure44.

Maternal diabetes-induced oxidative stress suppresses Wnt target gene expression, which is critical for normal cardiogenesis. Deletion of the canonical Wnt target gene, Versican, induces exclusively VSDs45, whereas null mutations of the noncanonical Wnt target gene, Mrtf-b, mainly causes outflow tract defects46. These findings support the hypothesis that the canonical Wnt pathway is essential for the development of both ventricular septum and the outflow tract, whereas the noncanonical Wnt pathway is essentially involved in the development of the outflow tract. Human mutations of the GJA1 gene, a canonical Wnt target gene, associating with HLHS (hypoplastic left heart syndrome)47, provide addition evidence that the canonical Wnt pathway support cardiac ventricular development. However, depending on cellular context, the canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling pathways can interact or counteract with each other48. Because deletion of negative regulators of the Wnt pathway such as DKK149 and GSK-3β50 also produces heart defects similar to those in null mutations of Wnt positive regulators, a fine-tuned Wnt signal, not less or not too much, is required for the formation of a structurally normal heart.

SOD1 overexpression did not rescue Wnt5a null-induced heart defects, indicating that heart defects that arise with KO of Wnt5a are not due to oxidative stress. In contrast under conditions of high oxidative stress as in diabetes Wnt5a signaling is suppressed and both its signaling and CHDs are rescued by SOD1 overexpression.

In summary, we provide direct in vivo evidence that oxidative stress mediates the teratogenicity of maternal diabetes leading to heart defects modeling those of diabetic human pregnancies. Maternal diabetes-induced oxidative stress suppresses both the canonical and noncanonical Wnt pathway through different mechanisms (Figure 7C). Whereas the canonical Wnt pathway is impeded because of the upregulation of its antagonists, the noncanonical pathway is blocked through the suppression of noncanonical Wnt5a expression. SOD1 restores the non-canonical Wnt signaling by preventing Wnt5a down-regulation. In the absence of Wnt5a, SOD1 is unable to restore the non-canonical Wnt signaling. Our results support the hypothesis that oxidative stress is the cause of impaired Wnt signaling in the developing heart and subsequent CHD formation in diabetic pregnancies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This study is supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01DK083243, R01DK101972, R01DK103024, R01HL65314 and an American Diabetes Association Basic Science Award (1-13-BS-220).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: None.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenkins KJ, Correa A, Feinstein JA, Botto L, Britt AE, Daniels SR, et al. Noninherited risk factors and congenital cardiovascular defects: current knowledge: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2007;115:2995–3014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loffredo CA, Wilson PD, Ferencz C. Maternal diabetes: an independent risk factor for major cardiovascular malformations with increased mortality of affected infants. Teratology. 2001;64:98–106. doi: 10.1002/tera.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wren C, Birrell G, Hawthorne G. Cardiovascular malformations in infants of diabetic mothers. Heart. 2003;89:1217–1220. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.10.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheffield JS, Butler-Koster EL, Casey BM, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. Maternal diabetes mellitus and infant malformations. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:925–930. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar SD, Dheen ST, Tay SS. Maternal diabetes induces congenital heart defects in mice by altering the expression of genes involved in cardiovascular development. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2007;6:34. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Machado AF, Zimmerman EF, Hovland DN, Jr, Weiss R, Collins MD. Diabetic embryopathy in C57BL/6J mice. Altered fetal sex ratio and impact of the splotch allele. Diabetes. 2001;50:1193–1199. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.5.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molin DG, Roest PA, Nordstrand H, Wisse LJ, Poelmann RE, Eriksson UJ, et al. Disturbed morphogenesis of cardiac outflow tract and increased rate of aortic arch anomalies in the offspring of diabetic rats. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70:927–938. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan SC, Relaix F, Sandell LL, Loeken MR. Oxidative stress during diabetic pregnancy disrupts cardiac neural crest migration and causes outflow tract defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2008;82:453–463. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wentzel P, Gareskog M, Eriksson UJ. Decreased cardiac glutathione peroxidase levels and enhanced mandibular apoptosis in malformed embryos of diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2008;57:3344–3352. doi: 10.2337/db08-0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roest PA, Molin DG, Schalkwijk CG, van Iperen L, Wentzel P, Eriksson UJ, et al. Specific local cardiovascular changes of Nepsilon-(carboxymethyl)lysine, vascular endothelial growth factor, and Smad2 in the developing embryos coincide with maternal diabetes-induced congenital heart defects. Diabetes. 2009;58:1222–1228. doi: 10.2337/db07-1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gessert S, Kuhl M. The multiple phases and faces of wnt signaling during cardiac differentiation and development. Circ Res. 2010;107:186–199. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.221531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu H, Ye X, Guo N, Nathans J. Frizzled 2 and frizzled 7 function redundantly in convergent extension and closure of the ventricular septum and palate: evidence for a network of interacting genes. Development. 2012;139:4383–4394. doi: 10.1242/dev.083352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamblet NS, Lijam N, Ruiz-Lozano P, Wang J, Yang Y, Luo Z, et al. Dishevelled 2 is essential for cardiac outflow tract development, somite segmentation and neural tube closure. Development. 2002;129:5827–5838. doi: 10.1242/dev.00164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavlinkova G, Salbaum JM, Kappen C. Wnt signaling in caudal dysgenesis and diabetic embryopathy. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2008;82:710–719. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schleiffarth JR, Person AD, Martinsen BJ, Sukovich DJ, Neumann A, Baker CV, et al. Wnt5a is required for cardiac outflow tract septation in mice. Pediatr Res. 2007;61:386–391. doi: 10.1203/pdr.0b013e3180323810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de la Pompa JL, Timmerman LA, Takimoto H, Yoshida H, Elia AJ, Samper E, et al. Role of the NF-ATc transcription factor in morphogenesis of cardiac valves and septum. Nature. 1998;392:182–186. doi: 10.1038/32419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bushdid PB, Osinska H, Waclaw RR, Molkentin JD, Yutzey KE. NFATc3 and NFATc4 are required for cardiac development and mitochondrial function. Circ Res. 2003;92:1305–1313. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000077045.84609.9F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sivan E, Lee YC, Wu YK, Reece EA. Free radical scavenging enzymes in fetal dysmorphogenesis among offspring of diabetic rats. Teratology. 1997;56:343–349. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199712)56:6<343::AID-TERA1>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang P, Cao Y, Li H. Hyperglycemia induces inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression and consequent nitrosative stress via c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:185, e185–e111. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roest PA, van Iperen L, Vis S, Wisse LJ, Poelmann RE, Steegers-Theunissen RP, et al. Exposure of neural crest cells to elevated glucose leads to congenital heart defects, an effect that can be prevented by N-acetylcysteine. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79:231–235. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Weng H, Reece EA, Yang P. SOD1 overexpression in vivo blocks hyperglycemia-induced specific PKC isoforms: substrate activation and consequent lipid peroxidation in diabetic embryopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:84, e81–e86. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weng H, Li X, Reece EA, Yang P. SOD1 suppresses maternal hyperglycemia-increased iNOS expression and consequent nitrosative stress in diabetic embryopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:448, e441–e447. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Weng H, Xu C, Reece EA, Yang P. Oxidative stress-induced JNK1/2 activation triggers proapoptotic signaling and apoptosis that leads to diabetic embryopathy. Diabetes. 2012;61:2084–2092. doi: 10.2337/db11-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Xu C, Yang P. c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1/2 and endoplasmic reticulum stress as interdependent and reciprocal causation in diabetic embryopathy. Diabetes. 2013;62:599–608. doi: 10.2337/db12-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang P, Li X, Xu C, Eckert RL, Reece EA, Zielke HR, et al. Maternal hyperglycemia activates an ASK1-FoxO3a-caspase 8 pathway that leads to embryonic neural tube defects. Sci Signal. 2013;6:ra74. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Logan CY, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDonnell SM, Weisser-Thomas J, Kubo H, Hanscome M, Liu Q, Jaleel N, et al. CaMKII negatively regulates calcineurin-NFAT signaling in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2009;105:316–325. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.194035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moazzen H, Lu X, Ma NL, Velenosi TJ, Urquhart BL, Wisse LJ, et al. N-Acetylcysteine prevents congenital heart defects induced by pregestational diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:46. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-13-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher SA, Langille BL, Srivastava D. Apoptosis during cardiovascular development. Circ Res. 2000;87:856–864. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Bartelings MM, Deruiter MC, Poelmann RE. Basics of cardiac development for the understanding of congenital heart malformations. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:169–176. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000148710.69159.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sallee D, Qiu Y, Liu J, Watanabe M, Fisher SA. Fas ligand gene transfer to the embryonic heart induces programmed cell death and outflow tract defects. Dev Biol. 2004;267:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugishita Y, Watanabe M, Fisher SA. Role of myocardial hypoxia in the remodeling of the embryonic avian cardiac outflow tract. Dev Biol. 2004;267:294–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bohuslavova R, Skvorova L, Sedmera D, Semenza GL, Pavlinkova G. Increased susceptibility of HIF-1alpha heterozygous-null mice to cardiovascular malformations associated with maternal diabetes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;60:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu C, Li X, Wang F, Weng H, Yang P. Trehalose prevents neural tube defects by correcting maternal diabetes-suppressed autophagy and neurogenesis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305:E667–E678. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00185.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masckauchan TN, Agalliu D, Vorontchikhina M, Ahn A, Parmalee NL, Li CM, et al. Wnt5a signaling induces proliferation and survival of endothelial cells in vitro and expression of MMP-1 and Tie-2. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:5163–5172. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Misra K, Matise MP. A critical role for sFRP proteins in maintaining caudal neural tube closure in mice via inhibition of BMP signaling. Dev Biol. 2010;337:74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin L, Cui L, Zhou W, Dufort D, Zhang X, Cai CL, et al. Beta-catenin directly regulates Islet1 expression in cardiovascular progenitors and is required for multiple aspects of cardiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:9313–9318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700923104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colla S, Zhan F, Xiong W, Wu X, Xu H, Stephens O, et al. The oxidative stress response regulates DKK1 expression through the JNK signaling cascade in multiple myeloma plasma cells. Blood. 2007;109:4470–4477. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-056747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elzi DJ, Song M, Hakala K, Weintraub ST, Shiio Y. Wnt antagonist SFRP1 functions as a secreted mediator of senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:4388–4399. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06023-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dahl E, Wiesmann F, Woenckhaus M, Stoehr R, Wild PJ, Veeck J, et al. Frequent loss of SFRP1 expression in multiple human solid tumours: association with aberrant promoter methylation in renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2007;26:5680–5691. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vibhakar R, Foltz G, Yoon JG, Field L, Lee H, Ryu GY, et al. Dickkopf-1 is an epigenetically silenced candidate tumor suppressor gene in medulloblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2007;9:135–144. doi: 10.1215/15228517-2006-038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huh SH, Ornitz DM. Beta-catenin deficiency causes DiGeorge syndrome-like phenotypes through regulation of Tbx1. Development. 2010;137:1137–1147. doi: 10.1242/dev.045534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sakata Y, Kamei CN, Nakagami H, Bronson R, Liao JK, Chin MT. Ventricular septal defect and cardiomyopathy in mice lacking the transcription factor CHF1/Hey2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16197–16202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252648999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hatano S, Kimata K, Hiraiwa N, Kusakabe M, Isogai Z, Adachi E, et al. Versican/PG-M is essential for ventricular septal formation subsequent to cardiac atrioventricular cushion development. Glycobiology. 2012;22:1268–1277. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oh J, Richardson JA, Olson EN. Requirement of myocardin-related transcription factor-B for remodeling of branchial arch arteries and smooth muscle differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15122–15127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507346102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dasgupta C, Martinez AM, Zuppan CW, Shah MM, Bailey LL, Fletcher WH. Identification of connexin43 (alpha1) gap junction gene mutations in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) Mutat Res. 2001;479:173–186. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(01)00160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bryja V, Schulte G, Rawal N, Grahn A, Arenas E. Wnt-5a induces Dishevelled phosphorylation and dopaminergic differentiation via a CK1-dependent mechanism. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:586–595. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips MD, Mukhopadhyay M, Poscablo C, Westphal H. Dkk1 and Dkk2 regulate epicardial specification during mouse heart development. Int J Cardiol. 2011;150:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kerkela R, Kockeritz L, Macaulay K, Zhou J, Doble BW, Beahm C, et al. Deletion of GSK-3beta in mice leads to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy secondary to cardiomyoblast hyperproliferation. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3609–3618. doi: 10.1172/JCI36245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.