Abstract

Background

The potential of expression profiling using microarray analysis as a tool to predict the prognosis for different types of cancer has been realized. This study aimed to identify a novel biomarker for colorectal cancer (CRC).

Methods

The expression profiles of cancer cells in 152 patients with stage I-III CRC were examined using microarray analysis. High expression in CRC cells, especially in patients with distant recurrences, was a prerequisite to select candidate genes. Thus, we identified seventeen candidate genes, and selected Traf2- and Nck-interacting kinase (TNIK), which was known to be associated with progression in CRC through Wnt signaling pathways. We analyzed the protein expression of TNIK using immunohistochemistry (IHC) and investigated the relationship between protein expression and patient characteristics in 220 stage I-III CRC patients.

Results

Relapse-free survival was significantly worse in the TNIK high expression group than in the TNIK low expression group in stage II (p = 0.028) and stage III (p = 0.006) patients. In multivariate analysis, high TNIK expression was identified as a significant independent risk factor of distant recurrence in stage III patients.

Conclusion

This study is the first to demonstrate the prognostic significance of intratumoral TNIK protein expression in clinical tissue samples of CRC, in that high expression of TNIK protein in primary tumors was associated with distant recurrence in stage II and III CRC patients. This TNIK IHC study might contribute to practical decision-making in the treatment of these patients.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12885-015-1783-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Biomarker, Microarray analysis, Traf2- and Nck- interacting kinase (TNIK), Prognostic factor

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide, and the third leading cause of cancer death in Japan [1]. Although curative surgery is performed, approximately 30 % of CRC patients develop recurrences [2]. In particular, recurrences in distant organs or distant lymph nodes (distant recurrences) have a critical impact on the prognosis of CRC.

The TNM classification system of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) has been used as a standard tool for prognostic stratification and has provided valuable information for therapeutic decision-making, such as the selection of suitable candidates for adjuvant chemotherapy. However, TNM classification is limited in its ability to predict the exact prognosis of individual CRC patients. For further improvement in the prognosis for CRC patients and individualization of cancer therapy, molecular biological approaches have been intensely studied recently.

Expression profiling using microarray analysis allows the exploration of several thousand cancer-related or cancer-specific genes in the search for candidate genes amenable to prognosis prediction and classification of human malignancies [3–5]. A number of genes that were poor prognostic markers have been identified in CRC patients (e.g., NUCKS1, BNIP3, PDGFC, OPG) using microarray analysis; their prognostic significance was subsequently assessed in surgically resected CRC subjects by mRNA and/or immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses [6–9].

In this study, we identified Traf2- and Nck-interacting kinase (TNIK) using microarray analysis as a candidate gene that was related to distant recurrence of CRC. TNIK is a member of the germinal center kinase family, and is reported to be essential for Wnt signaling and CRC proliferation and progression [10, 11]. However, the correlation between intratumoral TNIK expression and the prognosis of CRC patients has not yet been reported. This study aimed to confirm the prognostic significance of TNIK in CRC through investigation of the relationship between intratumoral TNIK protein expression and the prognosis of CRC patients.

Methods

Patients

Primary tumors from 1210 consecutive patients who underwent surgical resection for CRC between 2002 and 2009 at Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital were included in this study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Study published by the Japanese government. The Ethical Committee of Tokyo Medical and Dental University Hospital approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

A total of 152 patients were assigned to the microarray analysis, including 27 patients with stage I, 69 patients with stage II, 56 patients with stage III disease. Distant recurrences (not including local recurrences) occurred in 26 patients. Patient characteristics of these subjects for microarray analysis were shown in Additional file 1. The median follow-up time at the analysis was 60 months (range 15–76 months).

For the protein expression analysis using immunohistochemistry (IHC), the different 220 patients were studied; 48, 87, and 85 patients with stage I, II, and III CRC, respectively. Distant recurrences occurred in 53 patients. The median follow-up time at the analysis was 61 months (range 1–141 months).

RNA extraction

Cancer tissues were immediately embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek Japan, Tokyo, Japan) after surgical resection. Serial frozen sections of 9-μm thickness were mounted onto a foil-coated glass slide, 90 FOIL-SL25 (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), and laser capture microdissection (LCM) was carried out using the Application Solutions Laser Capture Microdissection System (Leica Microsystems). Total RNA from LCM of cancer tissues and normal colorectal epithelia were extracted using the RNeasy mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The integrity of the obtained total RNA was assessed using an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA), and samples with an RNA integrity number greater than 5.0 were used for microarray analysis.

Oligonucleotide microarray analysis

cRNA was prepared from 100 ng total RNA using two-cycle target labeling and a control reagents kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Hybridization and signal detection of the Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix) were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The gene expression data was deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession ID GSE71222 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=izcnsaygjjkpped&acc=GSE71222).

The gene expression data were then analyzed to identify the candidate genes related to distant recurrence. We defined the patients with distant recurrence as the recurrence group, and the patients without any distant recurrences as the non-recurrence group. The criteria to select candidate genes were as follows; (i) a higher expression level in cancer tissues than in non-cancerous mucosa, (ii) a significantly higher expression level in cancer cells of the recurrence group than in the non-recurrence group. A higher expression was defined as a numerical value 1.5 times greater than those in another group.

Immunohistochemistry

A streptavidin-biotin method was used for TNIK immunostaining. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks from each patient were cut at 4-μm thickness. After deparaffinization in xylene and rehydration through a series of incubations in decreasing concentrations of ethanol, antigens were retrieved from the tissues by autoclaving them at 121 °C for 2 min in pH 8.0 citrate buffer. The sections were then incubated in a solution of 3 % hydrogen peroxide in 100 % methanol for 15 min at room temperature in order to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Nonspecific binding was blocked by treating the tissues with 10 % normal goat serum (Nichirei Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan) for 15 min. Thereafter, the slides were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against TNIK at a 1:400 dilution (HPA012128; Sigma-Aldrich, Co. LLC., St Louis, MO) for 30 min at room temperature and for overnight at 4 °C. Next, sections were incubated with labeled polymer [Histofine® Simple Stain MAX PO (MULTI); Nichirei Bioscience] for 30 min at room temperature. Color development was carried out with DAB (0.02 % 3, 30-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride; Nichirei Bioscience) for 7 min at room temperature. The slides were counterstained with 1 % Mayer’s hematoxylin, after which they were dehydrated using a series of increasing alcohol concentrations, immersed in xylene, and finally coverslipped.

All sections were scored by two investigators. The staining intensity was scored as 0 (negative), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), or 3 (strong). The staining extensity was scored as 1 (0–10 % of the tumor cells stained), 2 (11–40 %), 3 (41–70 %), or 4 (71–100 %). The sum of the intensity and extensity scores, potentially ranging from 1 to 7, was calculated, and the average of three fields (magnification 100×) that were strongly stained at the tumor front were used to determine the TNIK IHC-staining score for each patient.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 17.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). To estimate the significance of differences between the groups, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Mann–Whitney U test, and χ2 test were used where appropriate. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time from the date of surgery to distant recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of surgery to death from any cause. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and curves were compared using the log-rank test. Factors affecting RFS and OS were examined with univariate and multivariate analyses using the Cox proportional hazards model. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Microarray analysis

In the microarray analysis, 69 genes were identified that fulfilled the above-mentioned criteria. The heat map of 69 genes is shown in Additional file 2. Among 69 genes, 17 genes were reported to be associated with human malignancies. The list of selected 17 genes is shown in Additional file 3. Among 17 candidate genes, we focused on 5 genes (S100A2, TNIK, TESC, PROX1 and ZBED6) which reported to be associated with colorectal cancer. Another researcher in our laboratory is submitting a paper about S100A2. TESC, PROX1 and ZBED6 are being researched now. We selected TNIK as a target gene for further analysis for the following reasons; (i) TNIK is known to be associated with the progression of CRC through Wnt signaling pathways [10, 11], (ii) TNIK gene amplification was reported to be required for the progression of gastric cancer, and nuclear expression of TNIK in hepatocellular carcinoma was reported to be associated with poor prognosis [12, 13], (iii) the correlation between the expression levels of TNIK in CRC patients and their clinical outcomes have not been revealed. Co-expression analysis of 69 genes was performed using STRING DATA BASE (http://string-db.org/). The co-expression networks are shown in Additional file 4. Although some co-expression networks were observed, TNIK was not involved in those networks.

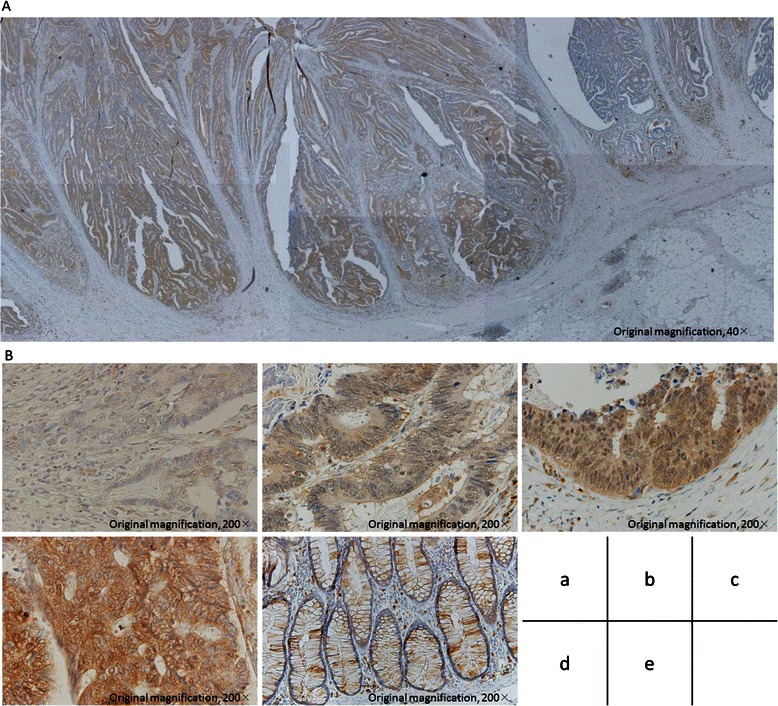

Expression of TNIK protein in CRC

Figure 1 shows the representative results of IHC staining of TNIK in CRC samples. TNIK protein was observed in the cytoplasm of cancer cells, but not in normal epithelial cells. The entire tumor cross-section showed heterogeneous staining; however, the staining tended to be strong at the invasive tumor front. Therefore, we focused on TNIK expression at the invasive tumor front, and used the staining scores at the invasive tumor front in further analysis.

Fig. 1.

TNIK immunostaining in representative CRC and normal colorectal epithelium. a Examining the entire tumor cross-section revealed that TNIK staining was heterogeneous. b (a) 0 no staining; (b) 1+ weak staining; (c) 2+ moderate staining; (d) 3+ strong staining; (e) normal epithelium staining

TNIK expression and patient characteristics

The median of the staining score of the 220 CRC patients studied was 5.3 (range 1-7). The scoring cut-off point was determined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. This was conducted for TNIK staining scores in comparison with CRC distant recurrence. The experimental samples were divided into 2 groups by the cut-off score: the low expression group (staining score < 6, n = 139) and the high expression group (staining score ≥ 6, n = 81).

Relationships between TNIK expression and patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. T4, right-sided colon cancer, lymphatic invasion, and venous invasion were significantly associated with high expression of TNIK. Samples from patients who developed distant recurrences showed higher TNIK expression than those from patients without distant recurrence.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and TNIK expression in stage I-III CRC patients

| Variables | TNIK expression | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 139) | High (n = 81) | |||

| Age | < 70 years | 98 | 53 | 0.435 |

| ≥ 70 years | 41 | 28 | ||

| Gender | male | 88 | 60 | 0.102 |

| female | 51 | 21 | ||

| Histology (TNM 7th) | G1 | 62 | 28 | 0.258 |

| G2 | 70 | 46 | ||

| G3 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Tumor location | right-sided colon | 26 | 28 | 0.016 |

| left-sided colon | 58 | 22 | ||

| rectum | 55 | 31 | ||

| Stage (TNM 7th) | I | 36 | 12 | 0.104 |

| II | 55 | 32 | ||

| III | 48 | 37 | ||

| Depth of tumor invasion (TNM 7th) | T1 | 17 | 6 | T1-3 vs. T4 0.002 |

| T2 | 32 | 11 | ||

| T3 | 58 | 29 | ||

| T4 | 32 | 35 | ||

| Lymphatic invasion | (-) | 50 | 17 | 0.021 |

| (+) | 89 | 64 | ||

| Venous invasion | (-) | 27 | 6 | 0.020 |

| (+) | 112 | 75 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | (-) | 91 | 44 | 0.102 |

| (+) | 48 | 37 | ||

| CEA*1 | < 5 ng/ml | 101 | 52 | 0.189 |

| ≥ 5 ng/ml | 38 | 29 | ||

| Distant recurrence | (-) | 118 | 49 | < 0.001 |

| (+) | 21 | 32 | ||

CEA*1 carcinoembryonic antigen

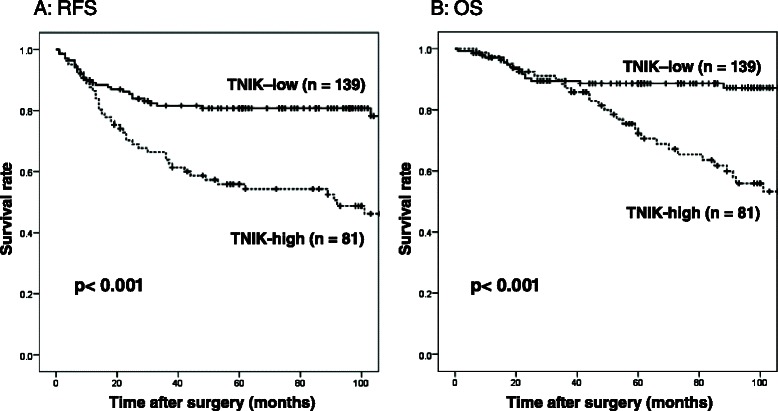

TNIK expression and prognosis of CRC patients

Figure 2a and 2b show RFS and OS curves stratified by TNIK expression group. RFS as well as OS in the TNIK high expression group was significantly worse (p < 0.001 log-rank test) than in those in the TNIK low expression group.

Fig. 2.

a RFS and (b) OS curves of 220 stage I-III CRC patients stratified by TNIK expression

In the univariate analysis, advanced age (≥70 years), poorly differentiated histology, T4, lymphatic invasion, venous invasion, lymph node metastasis, elevated carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level, and high TNIK expression were significantly associated with worse RFS. In the multivariate analysis, high TNIK expression, lymph node metastasis, and advanced age were identified as independent factors associated with worse RFS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of clinicopathologic variables affecting A: RFS and B: OS in patients with stage I-III CRC

| Variables | No. Patients | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | p value | Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | p value | |||

| ≪RFS≫ | ||||||

| Age | < 70 years | 151 | 0.614 (0.377–0.988) | 0.049 | 1.849 (1.115–3.067) | 0.017 |

| ≥ 70 years | 69 | |||||

| Gender | male | 148 | 1.709 (0.974–2.996) | 0.062 | ||

| female | 72 | |||||

| Histology (TNM 7th) | G1 | 90 | 0.485 (0.285–0.826) | 0.008 | 1.555 (0.884–2.737) | 0.125 |

| G2, G3 | 130 | |||||

| Tumor location | colon | 134 | 1.473 (0.911–2.382) | 0.114 | ||

| rectum | 86 | |||||

| Depth of tumor invasion (TNM 7th) | T1-3 | 153 | 2.713 (1.342–3.520) | 0.002 | 1.061 (0.616–1.827) | 0.832 |

| T4 | 67 | |||||

| Lymphatic invasion | (-) | 67 | 2.647 (1.386–5.054) | 0.003 | 1.344 (0.643–2.809) | 0.432 |

| (+) | 153 | |||||

| Venous invasion | (-) | 33 | 3.260 (1.186–8.959) | 0.022 | 1.334 (0.457–3.893) | 0.598 |

| (+) | 187 | |||||

| Lymph node metastasis | (-) | 135 | 3.316 (2.018–5.447) | < 0.001 | 2.326 (1.276–4.243) | 0.006 |

| (+) | 85 | |||||

| CEA | < 5 ng/ml | 153 | 2.239 (1.379–3.634) | 0.001 | 1.498 (0.907–2.473) | 0.114 |

| ≥ 5 ng/ml | 67 | |||||

| TNIK expression | low | 139 | 2.762 (1.694–4.502) | < 0.001 | 2.184 (1.310–3.641) | 0.003 |

| high | 81 | |||||

| Variables | No. Patients | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | p value | Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | p value | |||

| ≪OS≫ | ||||||

| Age | < 70 years | 151 | 2.842 (1.589–5.083) | < 0.001 | 2.887 (1.559–5.343) | 0.001 |

| ≥ 70 years | 69 | |||||

| Gender | male | 148 | 0.451 (0.218–0.936) | 0.032 | 0.598 (0.281–1.272) | 0.182 |

| female | 72 | |||||

| Histology (TNM 7th) | G1 | 90 | 2.046 (1.076–3.889) | 0.029 | 1.572 (0.788–3.137) | 0.199 |

| G2, G3 | 130 | |||||

| Tumor location | colon | 134 | 1.301 (0.726–2.332) | 0.376 | ||

| rectum | 86 | |||||

| Depth of tumor invasion (TNM 7th) | T1-3 | 153 | 3.047 (1.706–5.440) | < 0.001 | 1.693 (0.865–3.314) | 0.124 |

| T4 | 67 | |||||

| Lymphatic invasion | (-) | 67 | 2.368 (1.104–5.077) | 0.027 | 1.226 (0.517–2.909) | 0.643 |

| (+) | 153 | |||||

| Venous invasion | (-) | 33 | 4.483 (1.086–18.500) | 0.038 | 1.709 (0.385–7.591) | 0.481 |

| (+) | 187 | |||||

| Lymph node metastasis | (-) | 135 | 2.582 (1.435–4.648) | 0.002 | 1.505 (0.733–3.093) | 0.266 |

| (+) | 85 | |||||

| CEA | < 5 ng/ml | 153 | 2.608 (1.461–4.657) | 0.001 | 1.692 (0.929–3.082) | 0.086 |

| ≥ 5 ng/ml | 67 | |||||

| TNIK expression | low | 139 | 3.373 (1.838–6.192) | < 0.001 | 2.279 (1.205–4.310) | 0.011 |

| high | 81 | |||||

CI confidence interval

With respect to OS, univariate analysis indicated that advanced age, female gender, poorly differentiated histology, T4, lymphatic invasion, venous invasion, lymph node metastasis, elevated CEA level, and high TNIK expression were significantly associated with worse OS. High expression of TNIK and advanced age were identified as independent factors associated with worse OS by multivariate analysis (Table 2).

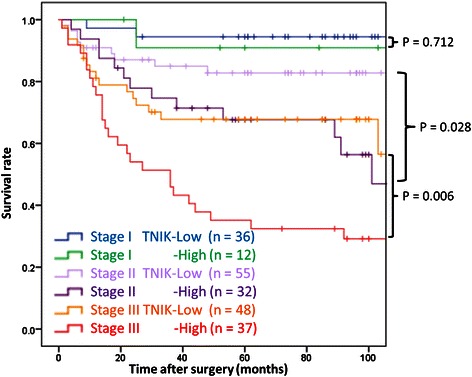

TNIK expression and prognosis of stage II and III patients

Figure 3 shows RFS curves stratified by TNM-7th stage and TNIK expression group.

Fig. 3.

RFS curves stratified by TNM-7th stage and TNIK expression

RFS curves were clearly separated by stage subgroup, and were also significantly separated by TNIK expression group in both stage II and III patients. RFS was significantly worse in the TNIK high expression group than in the TNIK low expression group in stage II (p = 0.028) and stage III (p = 0.006).

In the multivariate analysis, high TNIK expression was identified as a statistically significant and independent risk factor of distant recurrence in stage III patients, but not reached statistical significance in stage II (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of clinicopathologic variables affecting RFS in patients with A: stage II CRC and B: stage III CRC

| Variables | No. Patients | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | p value | Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | p value | |||

| ≪stage II≫ | ||||||

| Age | < 70 years | 53 | 2.984 (1.249–7.130) | 0.014 | 2.798 (1.168–6.702) | 0.021 |

| ≥ 70 years | 34 | |||||

| Gender | male | 53 | 0.506 (0.198–1.294) | 0.155 | ||

| female | 34 | |||||

| Histology (TNM 7th) | G1 | 36 | 1.041 (0.445–2.438) | 0.926 | ||

| G2, G3 | 51 | |||||

| Tumor location | colon | 57 | 1.723 (0.744–3.989) | 0.204 | ||

| rectum | 30 | |||||

| Depth of tumor invasion (TNM 7th) | T1-3 | 62 | 1.269 (0.517–3.115) | 0.603 | ||

| T4 | 25 | |||||

| Lymphatic invasion | (-) | 36 | 1.292 (0.541–3.083) | 0.564 | ||

| (+) | 51 | |||||

| Venous invasion | (-) | 11 | 1.550 (0.362–6.635) | 0.555 | ||

| (+) | 76 | |||||

| Examined lymph nodes | < 12 | 21 | 0.820 (0.321–2.097) | 0.679 | ||

| ≥ 12 | 66 | |||||

| CEA | < 5 ng/ml | 62 | 1.153 (0.450–2.954) | 0.767 | ||

| ≥ 5 ng/ml | 25 | |||||

| TNIK expression | low | 55 | 2.511 (1.073–5.877) | 0.034 | 2.323 (0.990–5.452) | 0.053 |

| high | 32 | |||||

| Variables | No. Patients | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | p value | Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | p value | |||

| ≪stage III≫ | ||||||

| Age | < 70 years | 60 | 1.032 (0.536–1.988) | 0.925 | ||

| ≥ 70 years | 25 | |||||

| Gender | male | 60 | 0.681 (0.334–1.385) | 0.289 | ||

| female | 25 | |||||

| Histology (TNM 7th) | G1 | 24 | 1.838 (0.878–3.846) | 0.106 | ||

| G2, G3 | 61 | |||||

| Tumor location | colon | 48 | 1.540 (0.839–2.824) | 0.163 | ||

| rectum | 37 | |||||

| Depth of tumor invasion (TNM 7th) | T1-3 | 43 | 1.308 | 0.388 | ||

| T4 | 42 | |||||

| Lymphatic invasion | (-) | 4 | 0.706 | |||

| (+) | 81 | |||||

| Venous invasion | (-) | 3 | 0.570 | |||

| (+) | 82 | |||||

| Lymph node metastasis (TNM 7th) | N1 | 48 | 0.194 | |||

| N2 | 37 | |||||

| CEA | < 5 ng/ml | 47 | 1.918 (1.042–3.530) | 0.036 | 1.678 (0.903–3.120) | 0.102 |

| ≥ 5 ng/ml | 38 | |||||

| TNIK expression | low | 48 | 2.345 (1.256–4.378) | 0.007 | 2.141 (1.136–4.038) | 0.019 |

| high | 37 | |||||

Discussion

This study is the first to demonstrate the prognostic significance of intratumoral TNIK protein expression in clinical tissue samples of CRC. Here, we found that there were some significant correlations between intratumoral TNIK protein expression and clinicopathologic features in CRC patients, with high TNIK expression being a significant prognostic factor of distant recurrence after curative surgery for stage II and III CRC.

TNIK is one of the germinal center kinase family members involved in cytoskeleton organization and neural dendrite extension [14–16], and is reported to be associated with the progression of several human cancers [12, 13]. Wnt signaling maintains the undifferentiated state of intestinal crypt cells through the T-cell for factor 4 (TCF4)/β-catenin-activating transcriptional complex. In CRC, activating mutations in Wnt pathway components lead to inappropriate activation of the TCF4/β-catenin transcriptional program and carcinogenesis [10]. Activation of the Wnt signaling cascade leads to disruption of the β-catenin degradation complex, resulting in β-catenin accumulation in the cytoplasm. β-catenin translocates to the nucleus, where it serves as a transcription factor to activate downstream target genes by binding to TCF4 [17–19]. TNIK is activated by β-catenin at the cytoplasm and translocates into the nucleus. Then, activated TNIK directly binds with both TCF4 and β-catenin and phosphorylates TCF4. The kinase activity of TNIK may be essential in TCF/lymphoid enhancer factor (LEF)-driven transcriptional activation of Wnt signaling pathways [11]. In the present study, high expression of TNIK was significantly associated with tumor depth (T4), lymphatic invasion, and venous invasion. This result suggests that elevated expression of TNIK may accelerate tumor progression and invasion.

We found that TNIK staining tended to be stronger at the invasive tumor front than at the tumor marginal site. The balance of pro- and anti-tumor factors at the invasive tumor front is reported to be decisive in determining tumor progression and the clinical outcome of patients with CRC [20, 21]. Our results supported the idea that high expression of TNIK at the invasive tumor front might play an important role in progression and distant metastasis of CRC.

Classification of risk of recurrence is intensively studied in the field of cancer treatment, because of its importance in treatment decision-making. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage III CRC is internationally accepted as a standard care for improving survival. de Gramont et al. indicated that stage III consists of subgroups of patients with various risks of recurrence, and proposed selecting treatment regimens from several options according to risk subgroup-specific survival data [22, 23]. On the basis of our results, stage III CRC patients with high TNIK expression may require strong adjuvant chemotherapy. For stage II disease, major western guidelines recommend adjuvant chemotherapy when patients have risk factors including T4 lesions, less than 12 lymph nodes examined, perforation, poorly differentiated histology, and lymphovascular involvement, even though the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II CRC has not been well-established and remains controversial [24]. Our results proposed that stage II CRC patients with high TNIK expression might be candidates for adjuvant chemotherapy as high-risk patients of distant recurrence.

Furthermore, the development of novel therapies that target critical biological pathways has greatly expanded treatment options for patients with CRC and resulted in substantial improvements in survival in the last decade [25, 26]. The Wnt signaling pathway has arisen as a target, and development of a new drugs targeting TNIK for CRC is in progress both in Japan and western country [27, 28].

Conclusions

High expression of TNIK protein in primary tumors was associated with distant recurrence in stage II and III CRC patients. This TNIK IHC study might contribute to practical decision-making in treatment for these patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Y. Takagi for the excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- TNIK

Traf2- and Nck- interacting kinase

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- IHC

Immunohistochemistry

- LCM

Laser capture microdissection

- GEO

the Gene Expression Omnibus

- RFS

Relapse-free survival

- OS

Overall survival

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- TCF4

T-cell for factor 4

- LEF

Lymphoid enhancer factor

Additional files

Patients’ characteristics for microarray analysis (N = 152). (PDF 260 kb)

Heat map of 69 genes. (PDF 255 kb)

Result of co-expression analysis of 69 genes. (PDF 230 kb)

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HT, TI and MI initiated the study, participated in its design and coordination, carried out the study, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. SO, KM, HK, SI, HM, Hiroshi T, HU and KS provided data, contribute to data interpretation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Hidenori Takahashi, Email: htsrg2@tmd.ac.jp.

Toshiaki Ishikawa, Phone: +81-3-5803-5261, Email: ishi.srg2@tmd.ac.jp.

Megumi Ishiguro, Email: ishiguro.srg2@tmd.ac.jp.

Satoshi Okazaki, Email: okazaki3332@gmail.com.

Kaoru Mogushi, Email: kmogushi@juntendo.ac.jp.

Hirotoshi Kobayashi, Email: h-kobayashi.srg2@tmd.ac.jp.

Satoru Iida, Email: s-iida@ohta-hp.or.jp.

Hiroshi Mizushima, Email: hmizushi@niph.go.jp.

Hiroshi Tanaka, Email: tanaka@cim.tmd.ac.jp.

Hiroyuki Uetake, Email: h-uetake.srg2@tmd.ac.jp.

Kenichi Sugihara, Email: sugi.srg2@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research. Cancer statistics in Japan 2013. http://ganjoho.jp/professional/statistics/backnumber/2013_jp.html

- 2.Kobayashi H, Mochizuki H, Sugihara K, Morita T, Kotake K, Teramoto T, et al. Characteristics of recurrence and surveillance tools after curative resectionfor colorectal cancer, a multicenter study. Surgery. 2007;141:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shih W, Chetty R, Tsao MS. Expression profiling by microarrays in colorectal cancer (Review) Oncol Rep. 2005;13:517–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kihara C, Tsunoda T, Tanaka T, Yamana H, Furukawa Y, Ono K, et al. Prediction of sensitivity of esophageal tumors to adjuvant chemotherapy by cDNA microarray analysis of gene-expression profiles. Cancer Res. 2001;61:6474–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Jatkoe T, Zhang Y, Mutch MG, Talantov D, Jiang J, et al. Gene expression profiles and molecular markers to predict recurrence of Dukes’ B colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1564–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kikuchi A, Ishikawa T, Mogushi K, Ishiguro M, Iida S, Mizushima H, et al. Identification of NUCKS1 as a colorectal cancer prognostic marker through integrated expression and copy number analysis. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2295–302. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu S, Iida S, Ishiguro M, Uetake H, Ishikawa T, Takagi Y, et al. Methylated BNIP3 gene in colorectal cancer prognosis. Oncol Lett. 2010;1:865–72. doi: 10.3892/ol_00000153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamauchi S, Iida S, Ishiguro M, Ishikawa T, Uetake H, Sugihara K. Clinical Significance of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-C Expression in Colorectal Cancer. J Cancer Ther. 2014;5:11–20. doi: 10.4236/jct.2014.51002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsukamoto S, Ishikawa T, Iida S, Ishiguro M, Mogushi K, Mizushima H, et al. Clinical significance of osteoprotegerin expression in human colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(8):2444–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahmoudi T, Li VS, Ng SS, Taouatas N, Vries RGJ, Mohammed S, et al. The kinase TNIK is an essential activator of Wnt target genes. EMBO J. 2009;28:3329–40. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shitashige M, Satow R, Jigami T, Aoki K, Honda K, Shibata T, et al. Traf2- and Nck-interacting kinase is essential for Wnt signaling and colorectal cancer growth. Cancer Res. 2010;70(12):5024–33. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu DH, Zhang X, Wang H, Zhang L, Chen H, Hu M, et al. The essential role of TNIK gene amplification in gastric cancer growth. Oncogenesis. 2014;2:e89. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2014.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin J, Jung HY, Wang Y, Xie J, Yeom YI, Jang JJ, et al. Nuclear expression of phosphorylated TRAF2- and NCK-interacting kinase in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with poor prognosis. Pathol Res Pract. 2014;210(10):621–7. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu CA, Shen M, Huang BC, Lasaga J, Payan DG, Luo Y. TNIK, a novel member of the germinal center kinase family that activates the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway and regulates the cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(43):30729–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taira K, Umikawa M, Takei K, Myagmar BE, Shinzato M, Machida N, et al. The Traf2- and Nck-interacting kinase as a putative effector of Rap2 to regulate actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(47):49488–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawabe H, Neeb A, Dimova K, Young SM, Jr, Takeda M, Katsurabayashi S, et al. Regulation of Rap2A by the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-1 controls neurite development. Neuron. 2010;65(3):358–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behrens J, von Kries JP, Kühl M, Bruhn L, Wedlich D, Grosschedl R, et al. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1996;382(6592):638–42. doi: 10.1038/382638a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huber O, Korn R, McLaughlin J, Ohsugi M, Herrmann BG, Kemler R. Nuclear localization of beta-catenin by interaction with transcription factor LEF-1. Mech Dev. 1996;59(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00597-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Wetering M, Cavallo R, Dooijes D, van Beest M, van Es J, Loureiro J, et al. Armadillo coactivates transcription driven by the product of the Drosophila segment polarity gene dTCF. Cell. 1997;88(6):789–99. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81925-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laghi L, Bianchi P, Miranda E, Balladore E, Pacetti V, Grizzi F, et al. CD3+ cells at the invasive margin of deeply invading (pT3-T4) colorectal cancer and risk of postsurgical metastasis: a longitudinal study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(9):877–84. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70186-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zlobec I, Lugli A, Baker K, Roth S, Minoo P, Hayashi S, et al. Role of APAF-1, E-cadherin and peritumoral lymphocytic infiltration in tumour budding in colorectal cancer. J Pathol. 2007;212(3):260–8. doi: 10.1002/path.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Gramont A, de Gramont A, Chibaudel B, Bachet JB, Larsen AK, Tournigand C, et al. From chemotherapy to targeted therapy in adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer. Semin Oncol. 2011;38(4):521–32. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rousseau B, Chibaudel B, Bachet JB, Larsen AK, Tournigand C, Louvet C, et al. Stage II and stage III colon cancer: treatment advances and future directions. Cancer J. 2010;16(3):202–9. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181ddc5bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology; Colon cancer version 3. 2013. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1408–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Douillard JY, Siena S, Cassidy J, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, et al. Randomized, phase III trial of panitumumab with infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) versus FOLFOX4 alone as first-line treatment in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer: the PRIME study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(31):4697–705. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.4860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada T, Shitashige M, Yokota K, Sawa M, Moriyama H. TNIK Inhibitor and the use. Publication date: 03.06.2010 Patent application number: 20100137386

- 28.Li VS, Mahmoudi T, Johannes CC. Inhibiting TNIK for treating colon cancer EP2305717A1 Publication date: 06.04.2011, Patent application number: 09170853.7

- 29.Liu C, Zhang Y, Li J, Wang Y, Ren F, Zhou Y, et al. p15RS/RPRD1A (p15INK4b-related sequence/regulation of nuclear pre-mRNA domain-containing protein 1A) interacts with HDAC2 in inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(15):9701–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.620872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang YH, Han SR, Kim JT, Lee SJ, Yeom YI, Min JK, et al. The EF-hand calcium-binding protein tescalcin is a potential oncotarget in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5(8):2149–60. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu X, Xin Z, Zhang W, Zheng S, Wu J, Chen K, et al. A missense polymorphism in ATF6 gene is associated with susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma probably by altering ATF6 level. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(1):61–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akhtar Ali M, Younis S, Wallerman O, Gupta R, Andersson L, Sjöblom T. Transcriptional modulator ZBED6 affects cell cycle and growth of human colorectal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(25):7743–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509193112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiener Z, Högström J, Hyvönen V, Band AM, Kallio P, Holopainen T, et al. Prox1 promotes expansion of the colorectal cancer stem cell population to fuel tumor growth and ischemia resistance. Cell Rep. 2014;8(6):1943–56. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bachet JB, Maréchal R, Demetter P, Bonnetain F, Cros J, Svrcek M, et al. S100A2 is a predictive biomarker of adjuvant therapy benefit in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(12):2643–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng H, Ishida M, Li L, Saito A, Kamiya A, Hamilton JP, et al. Pseudogene INTS6P1 regulates its cognate gene INTS6 through competitive binding of miR-17-5p in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(8):5666–77. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Li J, Wen S, Yang X, Zhang Y, Wang Z, et al. CHRM3 is a novel prognostic factor of poor prognosis in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7(5):902–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu H, Huang J, Peng J, Wu X, Zhang Y, Zhu W, et al. Upregulation of the inwardly rectifying potassium channel Kir2.1 (KCNJ2) modulates multidrug resistance of small-cell lung cancer under the regulation of miR-7 and the Ras/MAPK pathway. Mol Cancer. 2015;14(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0298-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Z, Wu K, Yang Z, Wu A. High-mobility group A2 overexpression is an unfavorable prognostic biomarker for nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015;409:155. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao Y, Slaney CY, Bidwell BN, Parker BS, Johnstone CN, Rautela J, et al. BMP4 inhibits breast cancer metastasis by blocking myeloid-derived suppressor cell activity. Cancer Res. 2014;74(18):5091–102. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson EO, Chang KH, de Pablo Y, Ghosh S, Mehta R, Badve S, et al. PHLDA1 is a crucial negative regulator and effector of Aurora A kinase in breast cancer. J Cell Sci. 2011;124(Pt 16):2711–22. doi: 10.1242/jcs.084970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong Y, Li J, Han F, Chen H, Zhao X, Qin Q, et al. High IGF2 expression is associated with poor clinical outcome in human ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep. 2015;34(2):936–42. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu L, Herman JG, Brock MV, Wu K, Mao G, Yan W, et al. Silencing DACH1 promotes esophageal cancer growth by inhibiting TGF-β signaling. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu YH, Chang TH, Huang YF, Huang HD, Chou CY. COL11A1 promotes tumor progression and predicts poor clinical outcome in ovarian cancer. Oncogene. 2014;33(26):3432–40. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schussel JL, Kalinke LP, Sassi LM, de Oliveira BV, Pedruzzi PA, Olandoski M, et al. Expression and epigenetic regulation of DACT1 and DACT2 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2015;15(1):11–7. doi: 10.3233/CBM-140436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]