Abstract

Background:

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and AmpC enzymes have been observed in virtually all species of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The β-lactamase producing bacteria cause many serious infections, including urinary tract infections. These enzymes are predominantly plasmid mediated. There are no recommended guidelines for detection of this resistance mechanism and there is a need to address this issue as much as the detection of ESBLs. This study was undertaken to characterize ESBL and AmpC producers among Escherichia coli by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which were initially screened by phenotypic method.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 90 isolates of E. coli were recovered from the urinary tract during a 7-month period, and were screened for ESBLs and AmpC production by disk diffusion test using cefoxitin (30 μg) disks and confirmed by combined disk diffusion test using phenyl boronic acid. The presence of genes encoding CIT, FOX, and TEM was detected by PCR.

Results:

On disk diffusion test, 59 of 90 isolates were resistant to third generation of cephalosporins; of these 37 (62.7%) and 3 (5%) were ESBL and AmpC producers, respectively. PCR showed that 29 (49.1%) and 3 (5%) were positive for blaTEM and blaCMY-2, respectively.

Conclusion:

ESBL- and AmpC-producing E. coli isolates cause significant resistance to cephalosporin. There is a need for a correct and reliable phenotypic test to identify AmpC β-lactamases and to discriminate between AmpC and ESBL producers. This work showed that boronic acid can differentiate ESBL enzymes from AmpC enzymes.

Keywords: AmpC, antibiotics, Escherichia coli, extended spectrum β-lactamase

INTRODUCTION

Nosocomial infections caused by drug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria expressing extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) pose a serious therapeutic challenge to clinicians due to limited therapeutic options.[1] Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the second most common type of infection in the body.[2] The most common cause of UTI is Gram-negative bacteria that belong to the family Enterobacteriaceae. Members of this family include Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, and Proteus.[3] During recent years, infections caused by ESBL-producing organisms have been increasingly diagnosed in outpatients.[4] ESBLs were first identified in 1983 and often located on plasmids that are transferable from strain to strain and between bacterial species; most of the enzymes are members of TEM families, which have been described in many countries.[5,6,7] It is worth mentioning that ESBLs are enzymes capable of hydrolyzing and inactivating a wide variety of β-lactams, including third-generation cephalosporin, penicillin, and aztreonam, but are susceptible to β-lacatamase inhibitors such as clavulanate, sulbactam, and tazobactam.[8] The TEM was first reported in E. coli isolated from a patient named Temoniera in Greece.[9] Since that time, these have been identified worldwide and have been found in a number of different organisms, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, E. coli, Proteus mirabilis, Enterobacter cloacae, Morganella morganii, Serratia marcescens, Shigella dysenteriae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Burkholderia cepacia, Capnocytophaga ochracea, Citrobacter, and Salmonella species.[10,11] Resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins can also be associated in E. coli with the production of plasmid class C β-lactamases, such as CMY-2 enzymes.[12] Plasmid-mediated AmpC β-lactamases represent a new threat since they confer resistance to cephamycins and are not affected by β-lactamase inhibitors. This resistance mechanism has been found around the world, can cause nosocomial outbreaks, and appears to be increasing in prevalence.[13] This study was undertaken to characterize ESBL and AmpC producers among E. coli by PCR, which were initially screened by phenotypic method.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All 90 strains of E. coli were isolated from the urine culture of hospitalized patients (in three major hospitals in Zahedan, south-eastern Iran) who suffered from UTIs during the period 2011-2012. Each sample was streaked on the blood and MacConkey agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) media and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. After incubation, E. coli isolates were detected by standard biochemical tests such as indole, methyl red, Voges-Proskauer, and citrate.

Antibiogram

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed by the Kirby Bauer method on Mueller-Hinton agar according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) protocol.[14] In this method the bacteria were cultured on Muller-Hinton Agar plate then amoxicillin (25), tetracycline (30), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1.25 + 23.15), ceftazidime (30), ceftriaxone (10), gentamicin (10), nalidixin acid (30), difloxcacin (25), and cefotaxime (30) disks (Himedia, Mumbai, India) were placed on the media in 20-30 mm with other disks. The plates were incubated for 18-24 h at 37°C.

ESBL screening

A 0.5 McFarland of test isolates was swabbed on Mueller-Hinton agar plates and ceftazidime (30 μg) and ceftazidime-clavulanic acid (30/10 μg) disks (Heimedia, India) were placed on the medium at a distance of 30 mm. Inoculated plates were incubated overnight at 35°C. An organism exhibiting zone size increase of 5 mm or greater around the ceftazidime-clavulanic acid disk compared to the ceftazidime disk was considered indicative of ESBL production.[15] E. coli ATTCC 25922 and K. pneumoniae ATTCC 700603 were used as control strains. In accordance with the CLSI criteria, isolates with resistance to cefoxitin were selected for further study.

AmpC screening

The boronic acid disk (Heimedia, Mumbai, India) test was used for AmpC screening by inoculating Mueller-Hinton agar by the standard disk diffusion method and placing a disk containing 30 μg of cefoxitin and another containing 30 μg of cefoxitin and 400 μg of boronic acid onto the agar surface. Inoculated plates were incubated overnight at 35°C. The organism that demonstrated 5 mm or greater zone around the disk containing cefoxitin and boronic acid compared to the disk containing cefoxitin was considered as AmpC producer.[16]

DNA extraction and PCR

DNA was extracted from colonies grown on agar medium using the (MBST, Tehran, Iran) extraction kit, following the manufacturer's instructions.

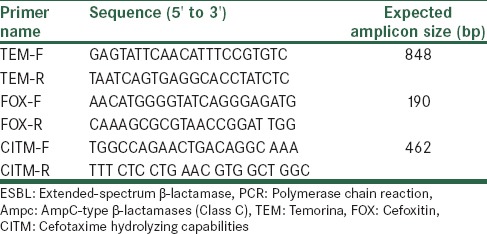

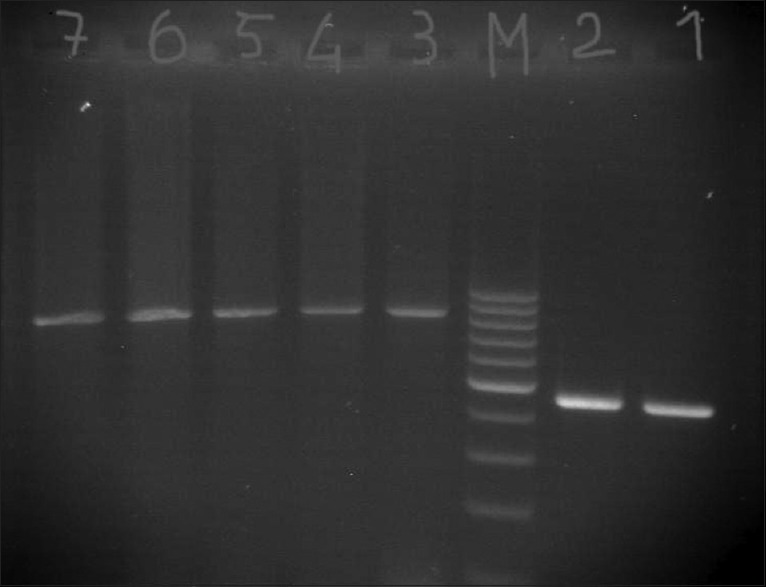

The specific primers and annealing temperatures used for amplifying the blaTEM, blaCITM, and blaFOX genes by PCR are shown in Table 1. In this study, K. pneumoniae ATCC 7881 was taken as the positive control for blaTEM expression, The PCR products were analyzed by agarose gels electrophoresis [Figure 1] and then the PCR product which was equivalent to expected amplification size in each cluster sent to Bioneer, Seoul, Korea for analyzing via sequencing.

Table 1.

The primer sequences of the ESBL and AmpC genes amplified by PCR

Figure 1.

PCR amplification of blaTEM and blaCITM Lane M = 100 bp DNA marker, Lanes 1 and 2 = Clinical isolates expressing blaTEM, Lanes 3–7 = Clinical isolates expressing blaCITM

RESULTS

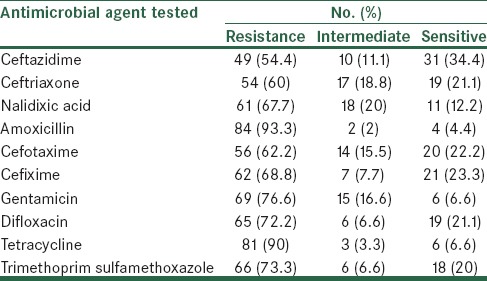

Among the 90 isolates tested, 31 were susceptible to all antibiotics tested, including third-generation cephalosporins. Of the remaining 59 isolates, 22 were resistant to cefoxitin and the remaining 37 were susceptible to it. ESBL phenotype was confirmed among all these 37 (62.7%) isolates by the combined disk diffusion (ceftazidime/ceftazidime-clavulanic acid). AmpC β-lactamase production was confirmed in 3 (13.6%) of 22 cefoxitin-resistant isolates and in the remaining (n = 19), it was not detectable. Antibiotic susceptibility of 90 E. coli isolates was evaluated for 10 antimicrobials. The majority of E. coli isolates were resistant to all 10 agents, including amoxicillin (93.3%), tetracycline (90%), cefixime (87.5%), nalidixic acid (85%), gentamicin (76.6%), trimethoprim (73.3%), difloxacin (72.2%), cefotaxime (62.2%), ceftriaxone (60%), and ceftazidime (54.4%) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of 90 strains of E. coli

PCR was performed on all 59 resistant isolates; the amplification of TEM, CITM, and FOX revealed 29 (49.1%), 3 (5%), and 0 (0%) isolates harbored the gene, respectively, and the rest of them were negative.

DISCUSSION

Resistance to β-lactam antibiotics of Gram-negative bacteria isolated from clinical samples has been increased worldwide.[17] For example, among 7054 E. coli samples collected between 1994 and 1996 in Barcelona (Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau), the prevalence of ESBL-producing strains was 0.14% (16). In 2001, this prevalence increased to 2.1%.[18] The prevalence of AmpC-producing E. coli isolates in Iran is not known due to limited number of studies and the difficulty that laboratories have in detecting the resistance mechanisms. The results of this study showed the prevalence of ESBL- and AmpC-producing E. coli to be 62.7% and 13.6%, respectively, by disk diffusion test, and 49.1% and 5% of the isolates harbored the genes encoding TEM and CITM with PCR method. The gene encoding FOX was not detected in any sample. In Iran, AmpC prevalence has been reported in Klebsiella spp. (5.95%) and E. coli (5.7%).[19,20] In another Iranian study, 3.3% of E. coli isolates produced AmpC β-lactamases.[13] A study from Canada showed that the annual incidence rates of AmpC were 1.7, 4.3, 11.2, and 15 per 100,000 residents for each year, respectively.[21] Jabeen et al. reported that the prevalence of the ESBL-producing E. coli and K. pneumoniae was 41% in E. coli and 36% in K. pneumoniae isolates.[22] The prevalence of the ESBL-producing organisms in Taiwan was in the range of 8.5-29.8% in K. pneumoniae and 1.5-16.7% in E. coli.[23] Behroozi et al. showed that 21% and 12% of E. coli and K. pneumoniae isolates, respectively, were ESBL producers in Tehran.[24] Feizabadi et al. reported that 72% K. pneumoniae strains isolated from Tehran hospitals were ESBL producing.[25] Tasli and Bahar and Al-Agamy et al. showed the rates of prevalence of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae to be 57.1% and 55%, respectively.[26,27] Based on the criteria of CLSI, cefoxitin resistance is used a marker for detection of AmpC-producing isolates; but in our study, significant numbers of cefoxitin-resistant isolates were not positive for AmpC production, hence other mechanisms of resistance should be considered.[12] CMY-2 is the most prevalent of the plasmid-mediated AmpC enzymes in our hospitals. The rate of CMY-2 (5%) in this study was very similar to that reported in Spain and lower than that reported in Belgian hospitals.[28,29] ESBLs and AmpC β-lactamases were first described in 1983 (Germany) and 1988 (India), respectively.[30,31] Some ESBLs may fail to reach a level to be detectable by disk diffusion tests, but result in treatment failure in the infected patient. There is a need for a correct and reliable phenotypic test to identify AmpC β-lactamases and to discriminate between AmpC and ESBL producers. It seems necessary for clinicians and healthcare systems to be fully aware of ESBLs and AmpC-producing microorganisms. Also, the ESBLs and AmpC production monitoring is recommended to avoid treatment failure and for suitable infection control in Iran.

The increasing drug resistance of bacteria is the major cause of treatment failure of UTI. This study shows the necessity for a rapid and simple test based on CLSI recommendations and rational antimicrobial therapy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This work was funded by a grant from Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sharma J, Sharma M, Ray P. Detection of TEM and SHV genes in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in a tertiary care hospital from India. Indian J Med Res. 2010;132:332–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moges AF, Genetu A, Mengistu G. Antibiotic sensitivities of common bacterial pathogens in urinary tract infections at Gonder hospital, Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 2002;79:140–2. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v79i3.8893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Souza RM, Olsburgh J. Urinary tract infection in the renal transplant patient. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2008;4:252–64. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez-Baño J, Navarro MD, Romero L, Martínez-Martínez L, Muniain MA, Perea EJ, et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in nonhospitalized patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1089–94. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.3.1089-1094.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernández JR, Martínez-Martínez L, Cantón R, Coque TM, Pascual A Spanish Group for Nosocomial Infections (GEIH) Nationwide study of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Spain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2122–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.5.2122-2125.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YK, Pai H, Lee HJ, Park SE, Choi EH, Kim J, et al. Bloodstream infections by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in children: Epidemiology and clinical outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1481–91. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1481-1491.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalematizadeh E. Mashhad: Mashhad University of Medical Sciences; 2008. Determination of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases bacteria in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford PA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the 21st century: Characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:933–51. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.933-951.2001. table of contents. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramazanzadeh R, Farhadifar F, Mansouri M. Etiology and antibiotic resistance patterns of community-acquired extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing gram negative isolates in Sanandaj. Res J Med Sci. 2010;4:243–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Philippon A, Labia R, Jacoby G. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1131–6. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.8.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goussard S, Courvalin P. Updated sequence information for TEM beta-lactamase genes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:367–70. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacoby GA, Munoz-Price LS. The new beta-lactamases. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:380–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shayan S, Bokaeian M, Shahraki S. Prevalence and molecular characterization of AmpC-producing clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from southeastern Iran. Microb Drug Resist. 2014;20:104–7. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI); 2010. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Twentieth Informational Supplement M100-S20; pp. 32–43. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peter-Getzlaff S, Polsfuss S, Poledica M, Hombach M, Giger J, Böttger EC, et al. Detection of AmpC beta-lactamase in Escherichia coli: Comparison of three phenotypic confirmation assays and genetic analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2924–32. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00091-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coudron PE. Inhibitor-based methods for detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamases in Klebsiella spp., Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:4163–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4163-4167.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goossens H. MYSTIC (Meropenem Yearly Susceptibility Test Information Collection) results from Europe: Comparison of antibiotic susceptibilities between countries and centre types. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46(Suppl B):39–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabaté M, Miró E, Navarro F, Vergés C, Aliaga R, Mirelis B, et al. Beta-lactamases involved in resistance to broad-spectrum cephalosporins in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. clinical isolates collected between 1994 and 1996, in Barcelona (Spain) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49:989–97. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mansouri S, Kalantar D, Asadollahi P, Taherikalani M, Emaneini M. Characterization of klebsiella pneumoniae strains producing extended spectrum beta-lactamases and AMPC type beta-lactamases isolated from hospitalized patients in kerman, Iran. Roum Arch Microbiol Immunol. 2012;71:81–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niakan M, Mohsen C, Metvaei AR. Prevalence of AmpC type extended spectrum beta lactamases genes in clinical, isolates of Klebsiella pneumonia. IJMS. 2008;2:1–8. [Persian] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitout JD, Gregson DB, Church DL, Laupland KB. Population-based laboratory surveillance for AmpC beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli, Calgary. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:443–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1303.060447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jabeen K, Zafar A, Hasan R. Frequency and sensitivity pattern of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing isolates in a tertiary care hospital laboratory of Pakistan. J Pak Med Assoc. 2005;55:436–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu WL, Chuang YC, Walther-Rasmussen J. Extended-spectrum beta -lactamases in Taiwan: Epidemiology, detection, treatment and infection control. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2006;39:264–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Behrouzi A, Rahbar M, Vandyousefi J. Frequency of extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBLS) producing Escherichia coli and Klebseilla pneumonia isolated from urine in an Iranian 1000-bed tertiary care hospital. AJMR. 2010;4:881–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feizabadi MM, Mohamadi-Yeganeh S, Mirsalehian A, Mirafshar SM, Mahboobi M, Nili F, et al. Genetic characterization of ESBL producing strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae from Tehran hospitals. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:609–15. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taşli H, Bahar IH. Molecular characterization of TEM- and SHV-derived extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in hospital-based Enterobacteriaceae in Turkey. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2005;58:162–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Agamy MH, Shibl AM, Zaki SA, Tawfik AF. Antimicrobial resistance pattern and prevalence of metallo-β-lactamases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Saudi Arabia. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5:5528–33. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bogaerts P, Rodriguez-Villalobos H, Laurent C, Deplano A, Struelens MJ, Glupczynski Y. Emergence of extended-spectrum-AmpC-expressing Escherichia coli isolates in Belgian hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:1073–5. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Briñas L, Lantero M, de Diego I, Alvarez M, Zarazaga M, Torres C. Mechanisms of resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins in Escherichia coli isolates recovered in a Spanish hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:1107–10. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmed MO, Clegg PD, Williams NJ, Baptiste KE, Bennett M. Antimicrobial resistance in equine faecal Escherichia coli isolates from North West England. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2010;9:12. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomson KS. Controversies about extended-spectrum and AmpC beta-lactamases. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:333–6. doi: 10.3201/eid0702.010238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]