Abstract

INTRODUCTION

We recently showed that tagging-SNPs across the SNCA locus were significantly associated with increased risk for LB pathology in AD cases. However, the actual genetic variant(s) that underlie the observed associations remain elusive.

METHODS

We used a bioinformatics algorithm to catalogue Structural-Variants in a region of SNCA-intron4, followed by phased-sequencing. We performed a genetic-association analysis in autopsy series of LBV/AD cases compared with AD-only controls. We investigated the biological functions by expression analysis using temporal-cortex samples.

RESULTS

We identified four distinct haplotypes within a highly-polymorphic-low-complexity CT-rich region. We showed that a specific haplotype conferred risk to develop LBV/AD. We demonstrated that the CT-rich site acts as an enhancer element, where the risk haplotype was significantly associated with elevated levels of SNCA-mRNA.

DISCUSSION

We have discovered a novel haplotype in a CT-rich region in SNCA that contributes to LB pathology in AD patients, possibly via cis-regulation of the gene expression.

Keywords: LBV/AD, structural variants, phased sequencing, SNCA, Lewy body, gene expression

1. Introduction

Genetic associations of the SNCA gene have been reported with several neurodegenerative disorders that share the common pathology of Lewy bodies (LB), including Parkinson’s disease (PD) [1–14], multiple system atrophy (MSA) [15, 16], dementia with LB (DLB) [17] and LB variant of Alzheimer’s disease (LBV/AD) [18]. However, the actual genetic variant(s) that underlie the observed associations remain largely elusive.

The ENCODE project has suggested that a large amount of non-coding genomic DNA is actively involved in gene regulation [19–22]. DNA polymorphisms in these active non-coding regions, particularly structural variants (SVs; variants other than SNPs) are likely to affect gene regulation and may alter biological function. It has been suggested that SVs have regulatory functions in gene transcription [23–28] and splicing [29] that underscore their possible role in the etiology of human diseases including complex disorders. However, genetic investigations of SVs in relation to complex human diseases have been underrepresented mainly as a consequence of the lack of high-throughput platforms for assay of SVs comparable to high density SNP genotyping platforms for genome wide associations studies (GWAS).

Rep1, a highly polymorphic, complex microsatellite repeat, which is located ~10Kb upstream of the SNCA gene, exemplified the important role of structural variants in a complex neurodegenerative disease. Rep1 was associated repeatedly with increased risk to develop late-onset PD [11, 30–33]. We further investigated the genetic association of Rep1 with biological functions and demonstrated that Rep1 acts as a transcription regulator of the gene, with the risk allele associated with elevated levels of SNCA-mRNA [24, 34–37]. With the exception of Rep1, no other structural variant has been firmly implicated in the etiology of sporadic PD and related complex diseases.

About 15–20% of demented patients with AD also have cortical and subcortical LBs [38] [39].It has been suggested that AD subjects with LB comprise a distinct subset referred to as LBV/AD [40]. We have recently shown that SNCA SNPs tagging both the 5’ and the 3’ linkage disequilibrium (LD) blocks were significantly associated with increased risk for LB pathology in AD cases, and demonstrated the genetic contribution of the SNCA locus to LBV/AD [18]. Herein we extend these findings to identify SVs within the SNCA locus that contribute to the risk of development of LBV/AD.

In this study, we focused on a defined region within the large intron 4 of SNCA as a model to design a stepwise strategy for cataloguing and dissecting candidate functional/causal SVs. With respect to the various terms used to describe SVs, Box 1 presents a glossary of the key terms used herein. Using a bioinformatics algorithm to catalogue and score SVs in this region, followed by deep sequencing analysis, we identified a highly polymorphic CT-rich region. We then performed a case-control genetic association analysis in an autopsy series of cases with LBV/AD compared with controls with AD only. We also completed an association analysis of the haplotypes of the CT-rich regions with SNCA mRNA expression to evaluate the functional and regulatory effects of this novel LB-risk structural variant.

Box 1 Glossary.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Structural variant | As broadly defined by Frazer et al.[49], these are all variants that are not single nucleotide variants. They include insertion–deletions, block substitutions, inversions of DNA sequences and copy number differences. |

| Low complexity | As defined by RepeatMasker.org, this is a genomic sequence consisting mainly of just two types of nucleotides. The ~160 bp region of low complexity discussed in this paper contains only deoxycytidine and thymidine residues when read on the sense strand of SNCA. |

| Haplotypes of the CT-rich region | The four haplotypes of this polymorphic region are illustrated in Fig. 2 and described in Table 4. |

| Phased sequencing | This is DNA sequencing of cloned regions that permits the determination of the haplotype phase of the alleles present. |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study samples

The study cohort consisted of individuals with two autopsy-confirmed neuropathological diagnoses: (1) LB variant of AD cases, i.e. LB co-occurred with AD pathology (LBV/AD, N=120); and (2) LB-free AD (AD, N=361) as controls for the genetic association analyses. All brain tissues were obtained through the Kathleen Price Bryan Brain Bank (KPBBB) at Duke University. Demographics and Neuropathology for these samples are shown in Table 1. Neuropathology phenotypes were determined in postmortem examination following widely-used and well-established methods. Two rating systems were used as a quantitative phenotype to confirm AD: (i) The severity degree of the intraneuronal neurofibrillary-tau pathology was scored using Braak[41] stage I–VI; (ii) Neuritic plaques were scored according to Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Criteria[42, 43]. The extent of plaque pathology was recorded postmortem and received scores of absent, mild, moderate, and severe. Neuropathology of LB was identified following the method and clinical practice recommendations of McKeith and colleagues [44, 45]. The overall severity degree of the LB pathology (based on examination of several affected brain regions) received scores of mild, moderate, severe and very severe.

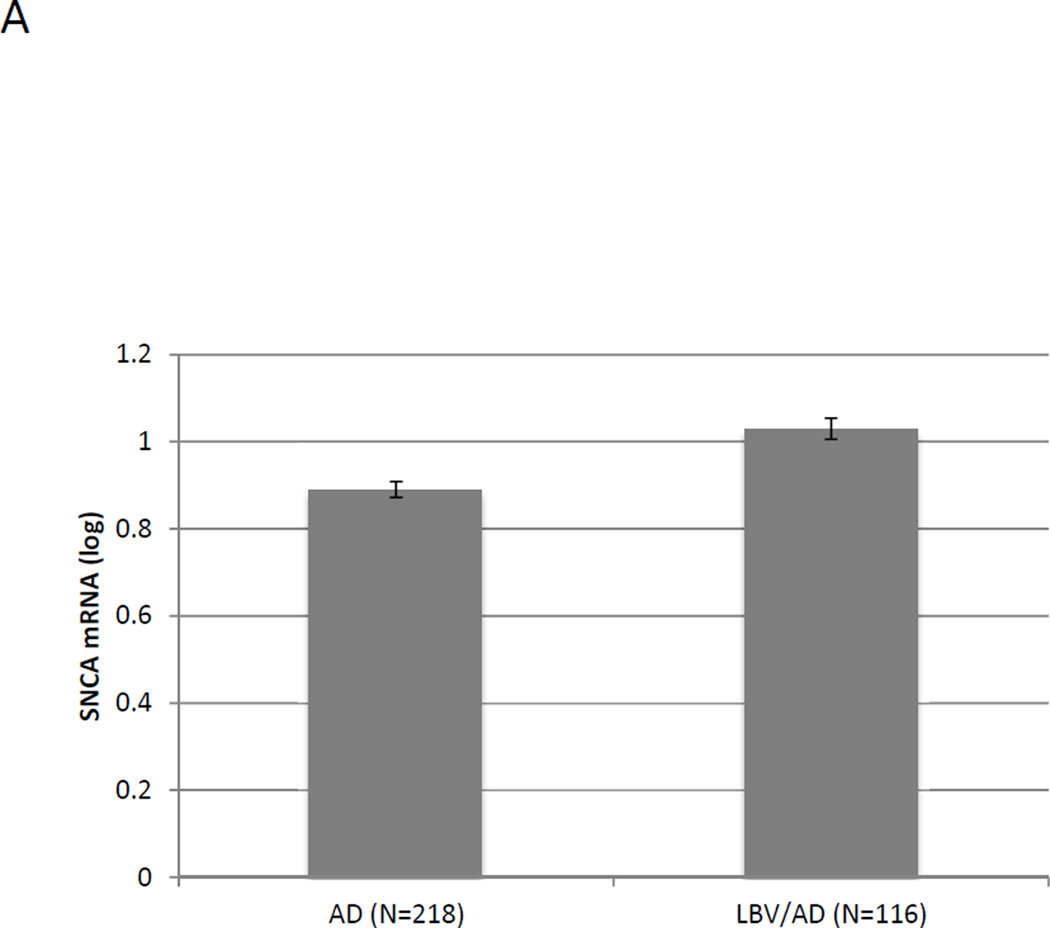

A sub-group was used for the expression analysis that includes temporal (TC) cortexes, from neuropathologies of LB variant of AD (LBV/AD: n=116) and LB-free AD (AD: n=218). All postmortem interval (PMI) were <24 hours.

2.2. Identification of structural variants with high probability for polymorphism

A searchable database of human structural genetic variation and a bioinformatics algorithm to empirically score variants for likelihood of exhibiting multiple alleles in the human genome were used to identify variants to test for association between SNCA genotypes and the LB phenotype. The structural variant database (dbSV, a proprietary database developed by Polymorphic DNA Technologies, Inc.) contains a complete list of the location of all insertions and deletions found in the public database dbSNP and also contains approximately 2 million simple sequence repeats (SSRs) including poly-T, poly-A, dinucleotide, trinucleotide and complex repeats that are derived by analysis of the human genome reference sequence. Each record of the database gives information on the chromosome location, associated gene, position within gene transcript, number of variant alleles, and size range of alleles. For each genetic variant, an impact score is calculated that corresponds to an empirical likelihood that a variant will exhibit multiple allelic forms in the human genome. The score is based on an equation that includes genomic context (intronic, exonic, promoter region), number of reported forms of variant alleles, size range of variants (for copy number variants and simple sequence repeats) as variables that are assigned empirical weights based on likelihood to have multiple polymorphic alleles (Supplemental Methods). For a genomic region, the distribution of scores is used to identify extreme values that have a higher likelihood of being polymorphic. Variants with high scores relative to the overall distribution were localized to small genomic regions (6 – 10Kb) that were further assessed for likelihood to affect gene regulation by examining whether there is an enrichment for ENCODE signals, relative to other regions of the SNCA gene. Regulatory/functional signals used included DNase I hypersensitivity sites, H3K4Me1 and H3K 27Ac marks, and evolutionary conservation.

2.3. SNP genotyping

Genotype determination of each single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was performed by allelic discrimination using TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Each genomic DNA sample (20 ng) was amplified using TaqMan Universal PCR master mix reagent (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) combined with the specific TaqMan SNP genotyping assay mix corresponding to the genotyped SNP. The assays were carried out using the ABI ViiA7 and the following conditions: 2 min at 50 °C 10 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles: 15 sec at 95 °C, and 1 min at 60 °C. Genotype determination was performed automatically using the SDS version 2.2 Enterprise Edition Software Suite (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). All genotypes were tested for Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium.

2.4. Phased sequencing: PCR, cloning and Sanger sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from brain tissues by the standard Qiagen protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). DNA samples from a subset of 95 subjects (51 LBV/AD and 44 age and sex matched AD cases) were plated on 96-well plates for PCR, cloning and DNA sequencing at Polymorphic DNA Technologies (Alameda, CA, USA). Briefly, the 521bp sequence around the highly-polymorphic low-complexity CT-rich region (chr4:90,742,300–90,742,820; GRCh37/hg19) was amplified by PCR using the Takara Taq Polymerase (Takara Mirus Bio, Inc., Madison, WI, USA) and the forward ‘AGAGACTTAAAATACATACCAACCAGAGATATAGTTTTG’ and the reverse ‘TGCCTACATTCTAGAAGGGAGAAATAAAATAAAAATCATACA’ primers. The PCR products were subsequently cloned into the pCR-TOPO-TA vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Next, 12 clones from each cloning-plate were picked and cultured in a 96-well format and the plasmid DNA templates were prepared using the TempliPhi DNA Sequencing Template Amplification kit (GE Healthcare/Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Sequence determination was performed by the standard Sanger sequencing method using the Big Dye, version 3.1 sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and four primers (the vector primers: M13F and M13R; and 2 internal primers: forward ‘GCCCTGACACGTTCT’ and reverse ‘GGAAAAAAAGTAGGGAGAC’), following the manufacture’s protocol. The sequencing reaction products were run on an ABI 3730XL DNA sequencer with a 50-cm capillary array using standard run mode. The sequence data was analyzed in two steps, first using the proprietary software Agent (Celera) to align the four sequencing reads for each clone and subsequently determining the two haplotypes set for each sample by the haplotype analysis software (Polymorphic DNA Technologies).

2.5. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from brain samples (100 mg) using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) followed by purification with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 260nm, while the quality of the purification was determined by 260nm/280nm ratio that showed values between 1.9 and 2.1, indicating high RNA quality. Additionally, quality of sample and lack of significant degradation products was confirmed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer. The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) measurements were greater than 7 validating the RNA quality control. Next, cDNA was synthesized using MultiScribe RT enzyme (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) under the following conditions: 10 min at 25 °C and 120 min at 37 °C.

2.6. Real time PCR

Real-time PCR was used to quantify the levels of human SNCA-mRNA [34, 36, 37, 46]. Briefly, duplicates of each sample were assayed by relative quantitative real-time PCR using the ABI ViiA7 to determine the level of SNCA message in brain tissues relative to mRNAs encoding the human neuronal proteins Enolase 2 (ENO2) and Synaptophysin (SYP). ABI MGB probe and primer set assays were used to amplify SNCA cDNA (ID Hs00240906_m1, 62bp); and the two RNA reference controls, ENO2 (ID Hs00157360_m1, 77bp) and SYP (ID Hs00300531_m1, 63bp) (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Each cDNA (10 ng) was amplified in duplicate in at least two independent runs (overall ≥ 4 repeats), using TaqMan Universal PCR master mix reagent (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and the following conditions: 2 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 95 °C, 40 cycles: 15 sec at 95 °C, and 1 min at 60°C. As a negative control for the specificity of the amplification, we used RNA control samples that were not converted to cDNA (no-RT) and no-cDNA/RNA samples (no-template) in each plate. No amplification product was detected in control reactions. Data were analyzed with a threshold set in the linear range of amplification. The cycle number at which any particular sample crossed that threshold (Ct) was then used to determine fold difference, whereas the geometric mean of the two control genes served as a reference for normalization. Fold difference was calculated as 2−ΔΔCt [47]; ΔCt=[Ct(SNCA)-Ct (reference)]. ΔΔCt =[ΔCt(sample)]-[ΔCt(calibrator)]. The calibrator was a particular brain RNA sample, obtained from a normal subject homozygous for haplotype 1, used repeatedly in each plate for normalization within and across runs. The variation of the ΔCt values among the calibrator replicates was smaller than 10%.

For assay validation we generated standard curves for SNCA and each reference assay, ENO2 and SYP using different amounts of human brain total RNA (0.1–100 ng). In addition, the slope of the relative efficiency plot for SNCA with each internal control (ENO2 or SYP) was determined to validate the assays. The slope in the relative efficiency plot for SNCA and the reference genes were <0.1, showing a standard value required for the validation of the relative quantitative method.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All analyses were carried out using SAS statistical software, Version 9.3 (SAS Institutes, Cary, NC). Statistical analyses were performed to assess association between each genetic variant and LB pathology. SNCA genotypes were coded with 0, 1 or 2 copies of the minor allele. Multivariable logistic regression analysis of the association between SNCA genotypes and LB phenotype was carried out using PROC LOGISTIC controlling for study age and sex.

Expression levels of SNCA mRNA of each sample were measured in replicate and the results were averaged. The mean expression of a group of samples was reported as mean±SE. We assessed the associations of the expression traits (SNCA-mRNA) with: 1) LB pathology, and 2) haplotypes of the CT-rich region, using the Generalized Linear Models procedure (PROC GLM). A log transformation (log2) was performed on all mRNA levels to assure normal distributions [48]. An additive genetic model was used and haplotypes were coded with 0, 1 or 2 copies of the risk haplotype. All models were adjusted for sex, age, PMI, and Braak and Braak stage. Correction for multiple testing employed the Bonferroni method.

3. Results

3.1. Determining the studied genomic region

Intron 4 of the SNCA gene is ~90Kb and spans a large proportion of the overall genomic sequence of the gene (~ 114Kb). To identify intronic genomic regions enriched for variants associated with regulation, we divided intron 4 into sub-regions based on overlap with DNaseI hypersensitivity sites (DHS), H3K4Me1, H3K 27Ac marks and strong RepeatMasker signals. For the present study, we focused on the 5’ end of intron 4, defining the initial region of interest (6,401bp) as 90,737,000–90,743,400 as a consequence of enrichment for strong ENCODE signals implying potential regulatory function. As shown in Figure 1 this non-coding region overlaps with regulatory functional signals including DNase I hypersensitivity sites, H3K4Me1 histone modification marks, and evolutionary conservation.

Fig. 1. Schematic of the investigated sub-region within SNCA intron4.

The region of interest (6,401bp) is positioned along Chr 4: 90,737,000–90,743,400 (GRCh37/hg19). The scheme indicates the relative location of the 521bp fragment (chr4:90,742,300–90,742,820; GRCh37/hg19; red horizontal line) that was selected for deep sequencing analysis. The position of each of the three analyzed SNPs is indicated (light blue vertical line). ENCODE regulatory tracks are annotated and their signals corresponded to their chromosomal location. Depicted functional element tracks include: DNaseI hypersensitivity cluster, H3K4Me1, H3K 27Ac, sequence alignments and conservation in vertebrates, RepeatMasker.

The dbSV search of intron 4 identified 169 potentially polymorphic variants, 9 variants having a high impact score of > 35 (Supplementary Table 1). Of the high scoring variants, 5 of 9 are located in the 5’ region of interest, these are highlighted in Table 2. Based on the location of the high scoring variants, the region of interest was narrowed to 521 bp (chr4:90,742,300–90,742,820; GRCh37/hg19). This region contains a long polypyrimidine repeat (all Cs and Ts on the “-” strand) defined by RepeatMasker as “low_complexity”.

Table 2.

Demographic and Neuropathology description

3.2. Association with LB pathology in AD

We evaluated the role of the highly-scored, structural-variant-rich region (521 bp) in the risk to develop LB pathology in AD patients. Thus for the purpose of this study we defined cases as autopsy confirmed LBs presentation co-occurring with AD pathology, and controls as confirmed AD only upon postmortem examination (i.e. free of LBs). The LBV/AD and AD sample sets consisted of neuropathologically well-characterized Caucasian samples (NAD=361, NLBV/AD=120, Table 1). Three SNPs positioned within the defined 521bp region (Fig. 1) were initially selected to test the association between this region in SNCA and the presence of LB in AD. All models were adjusted for age, sex and Braak stage. SNP rs2298728 was significantly associated with LB pathology in AD brains (p=0.0004, OR=2.6, 95% CI=1.54–4.41). The minor allele T (reverse strand) conferred increased risk to the development of LBs (Table 3). While two homozygotes for the minor allele were identified in the disease group (120 LBV/AD subjects), no homozygotes were found among the control larger group (361 AD subjects). SNPs rs17016251and rs35897584 demonstrated suggestive evidence of association (OR=1.16 and 1.44, respectively, Table 3) although these SNPs did not reach statistical significance (p=0.32 and 0.30, respectively, Table 3). After correction for multiple testing SNP rs2298728 remained highly significant (p=0.0012).

Table 3.

Catalogue of the high scoring SVs within theSNCAsub-region selected for sequencing analysis (chr4:90,742,300–90,742,820)

| Chromosome Position |

Variant Type |

Alleles | # of Known Variants in dbSNP |

Nucleotide Size Range in dbSNP |

Representative Variant Name |

SSR size |

Location Type |

# of Variants |

Size Range of Variation |

Total Potential Impact Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90,742,351 | LARGE | (LARGEINSERT ION)/- |

1 | 30 | rs67657106 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 60 | 72 |

| 90,742,463 | deletion | - /AGGAAGGAA GGAAGGGAGA AAGGA |

1 | 24 | rs145649402 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 48 | 60 |

| 90,742,474 | deletion | - /AAGGGAGAA AGGAAGGAAG GAAGG |

1 | 24 | rs66487639 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 48 | 60 |

| 90,742,476 | insertion | - /AAAGAAAGAA AGGAAAGAAA GT |

1 | 22 | rs142125351 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 44 | 56 |

| 90,742,495 | insertion | - /AAGTAAAGAA AGAAAGAAAA GA |

1 | 22 | rs67870596 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 44 | 56 |

3.3. Identification of the haplotypes of the CT-rich region

The strong LB-association led us to further investigate the 521 bp region by cloning and phased sequencing, followed by haplotype analysis. Sequencing of this 521bp region in 95 samples revealed a ~160 bp block of CT-rich region and a total 9 distinct variant sites, consisting of four SNPs, two deletions, two insertions, and a MNP. Table 4 shows the names, positions, descriptions, and variant frequencies of these 9 variants.

Table 4.

Association of SNPs in the SNCA 521bp region with LB pathology in AD

| rs Number | *Map position(bp) |

#MAF Case,Control |

Assoc. allele |

LBV/AD (p) | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2298728 | Chr4:90742815 | 0.117, 0.050 |

A |

0.0004 | 2.6 | 1.54–4.41 |

| rs35897584 | Chr4:90742692 | 0.093, 0.066 | G | 0.32 | 1.44 | 0.71–2.91 |

| rs17016251 | Chr4:90742639 | 0.472, 0.435 | C | 0.30 | 1.16 | 0.87–1.55 |

Total no., N=482; LBV/AD-Lewy body variant of Alzheimer’s disease

Map position based on dbSNP b126 build

MAF, the minor allele frequency

We next analyzed the 9 variations for their haplotype phase. Since there were 9 binary variant sites, a maximum of 512 possible haplotype combinations were possible. However, this analysis resulted in the identification of only four different haplotype combinations. The entire makeup of each of the four haplotypes is presented in Supplementary Table 4 and the resulting structures of the ~ 160 bp CT-rich portion of these four haplotypes is shown graphically in Fig. 2. The total size of these CT-rich haplotype sequences, in reference to the entire phased sequenced region, varied in length from 519 bp to 617 bp and their frequencies in the sequenced sample set of 188 chromosomes were 28%, 33%, 8%, and 31%, for haplotypes 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Notably, these haplotypes show a strong association with the presence of LB (p < 0.0001, likelihood ratio test, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2), supporting a genetic association for LB pathology. All of the samples containing at least one copy of haplotype 3 showed LBs; haplotype 3 showed substantial enrichment for the LB pathology followed by haplotype 2, while haplotypes 1 and 4 were most highly represented in the AD cases without LB (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Haplotype 3 is uniquely tagged by the minor allele (T(rev)) of SNP rs2298728 in this set of 95 samples (188 chromosomes) (Supplementary Tables 4), suggesting that it can be used as a proxy for the LB associated haplotype 3.

Fig. 2. Observed haplotypes of the CT-rich region.

The portion of the sequences shown corresponds to chr4:90,742,421–90,742,492 (GRCh37/hg19) on the minus strand. Identical sequences shared among the haplotypes are color coded.

3.4. Association with SNCA-mRNA expression levels

We evaluated the role of the complex CT-microsatellite on SNCA gene regulation. SNCA mRNA fold levels [SNCA/(ENO2, SYP)] were measured in 116 temporal cortex (TC) samples obtained from LBV/AD cases; and in 218 temporal cortex tissues from AD subjects. All brain tissue donors represent a subset group of the entire study samples from whom temporal cortex was available. We examined the cis-regulatory effect of the highly polymorphic CT-rich region on the total level of SNCA transcript (SNCA-mRNA).

We first tested for associations with confounding factors that might affect RNA levels. We did not detect significant associations of SNCA mRNAs levels with age, sex, postmortem interval (PMI), or Braak and Braak AD stage (data not shown), however, all of the subsequent analyses were adjusted for age, sex, PMI and Braak and Braak.

Subsequently, we examined the effect of LB pathology state on the expression of SNCA transcripts. SNCA mRNA levels were significantly increased in TC of LBV/AD-cases compared to AD control (p<0.0001; Fig. 3A), in agreement with our previous report [18].

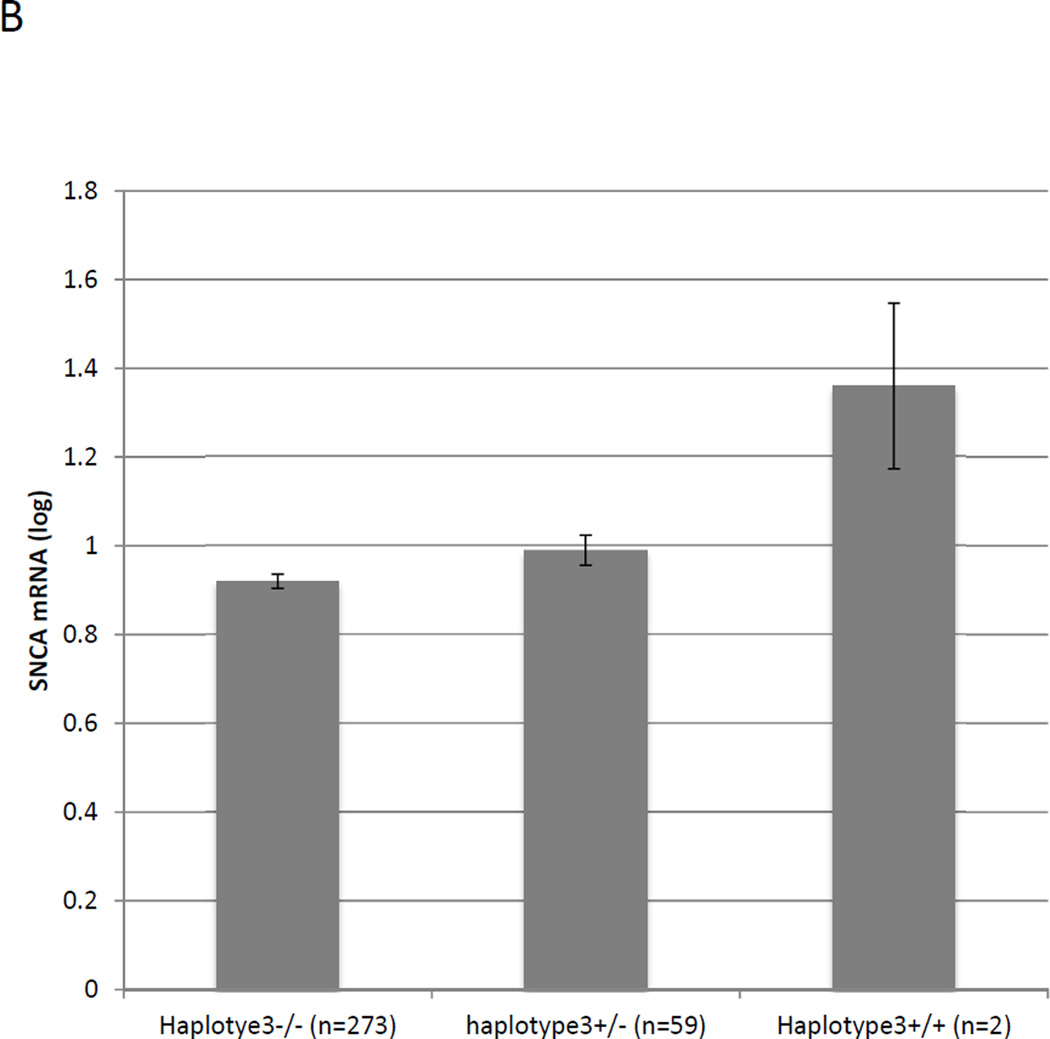

Fig. 3. >The effect of LB pathology and haplotype 3 on SNCA mRNA expression levels in human brain tissues.

The study cohort consisted of LBV/AD and AD temporal cortex (TC) tissues from Caucasian donors. Fold levels of human SNCA-mRNA were assayed by real-time RT-PCR using TaqMan technology, and calculated relative to the geometric mean of SYP- and ENO2- mRNAs reference control using the 2−ΔΔCt method (i.e. results presented are relative to a specific brain RNA sample). The values presented here are means levels±SE adjusted for age, gender, PMI and Braak and Braak stage. (A) General Linear Model (GLM) analysis showed that the diagnosis of co-occurrence of LB pathology is significantly associated with increased levels of SNCA mRNA (p<0.0001). (B) The subjects were genotyped for rs2298728 as proxy for haplotype 3 of the highly-polymorphic CT-rich region. GLM analysis showed that haplotype 3 was significantly associated with SNCA mRNA expression levels (p=0.02).

We next assessed whether haplotypes of the CT-rich region regulates SNCA gene-expression. Since our results indicated strong association between haplotype 3 of the CT-rich region and the presence of LB-pathology, we examined the functional consequences of the LB-risk haplotype 3. For analysis of the effect of haplotype 3 on mRNAs expression, LBV/AD and AD cases were pooled and the models were adjusted for disease status as well. We used SNP rs2298728 as a surrogate for genotyping and determining the number of copies of haplotype 3 in each subject. The highly polymorphic CT-rich region showed an effect on SNCA mRNA expression levels. Haplotype 3 of the CT-rich region was associated with higher levels of SNCA mRNA expression (N=334, p=0.02). Homozygotes for haplotype 3 demonstrated a nearly 50% increase in SNCA transcript levels compared to non-carriers of haplotype 3, although this is based on both of two samples from the only subjects who were homozygotes to haplotype 3. We also observed an additive mode of the association of haplotype 3 with the mean SNCA mRNA levels (Fig. 3B). Homozygous of haplotype 3+/+ genotype (n=2) showed the highest expression levels of SNCA-mRNA, followed by the heterozygotes haplotype 3+/− (n=59), and the homozygote genotype haplotype 3−/− presented the lowest levels (n=273) (Fig. 3B).

4. Discussion

Our study combined in silico and wet bench approaches to identify haplotypes of a polymorphic, intronic CT-rich region of SNCA that increase the risk to develop LB-pathology in AD patients. We also studied the biological relevance of these haplotypes and demonstrated a significant association with SNCA mRNA levels, indicating its plausible role as a regulator of SNCA transcription. Collectively, our results provided support to the concept that SNCA overexpression may be the underling molecular mechanism for the formation of LB, and identified a new intronic polymorphic element that contributes to the up-regulation of SNCA expression.

Genome-wide association studies based on SNPs have identified numerous associations between genomic regions and human disease. However translation of results from these studies to functional, causal variants has been challenging and these studies have not accounted for a substantial fraction of the heritable basis for complex diseases. Consideration of structural variation, in the broadest sense as “non-SNP variation”, has been identified as a critical step to identify causal variants and to understand the genetic architecture of complex traits [49]. This variation includes insertion/deletion variants, copy number variants, inversions, block substitutions and various types of repeating sequence. The false discovery rate and detection power of small indel polymorphisms indels is comparable to that of SNPs [50]. Montgomery et al. presented data showing that high rates of indel mutagenesis are observed in microsatellites and that these represent the extreme end of a spectrum of rate heterogeneity driven by local repeat structure which apply to mononucleotide runs, tandem repetitive tracts and nearly-repetitive regions of all lengths [50]. Short tandem repeat variations contain high information content as a consequence of rapid mutations and presence of multiple alleles and potentially will account for some of the missing heritability observed for complex traits [51]. Single molecule sequencing has enabled sequencing to resolve repeat structures at read lengths of 5–6 kb and results from these experiments have demonstrated a greater complexity in the human genome of longer and more complex repetitive DNA [52]. Moreover, for genetic analysis of many complex diseases, knowledge of individual diplotypes, from phased sequence data is critical to understand phenotypic expression[53]. In the present study, the availability of phased sequence data was essential to identify the specific subset of haplotypes that is associated with the LB disease phenotype. Prior human genetic studies of the LB phenotype were limited to genotypes and therefore did not account for the important aspect of phase-specific characterization of genetic variation reported in our study. Overall, the investigation of complex repetitive structures, microsatellites, insertion/deletion polymorphisms and specific haplotypes determined from phased sequence data is a relevant approach to identify highly informative variants that are associated with complex phenotypes including neurodegenerative diseases.

In this study we developed and employed a novel stepwise strategy to advance the identification of causal/functional variants within a disease-associated locus. We embarked on an effort to explore the role of SVs in neurodegenerative disorders including LB-related diseases and the functional mechanism through which SVs contribute to the risk to develop this group of diseases. Therefore we established a strategy that focuses primarily on structural variants. We developed a bioinformatics algorithm to annotate and catalogue candidate functional/causal SVs based on a scoring system. The output provides guidance for targeting regions for deep sequencing analysis. Deep sequencing is conducted in a human case-control cohort to determine the candidate SVs variability in a human population and to determine whether they are enriched in cases vs. control or vice versa. Next we dissect candidate SVs that meet these criteria to be examined in follow-up studies using biological systems and functional assays. Our stepwise strategy was employed in this study for exploring the role of SNCA in LBV/AD and presented a model for follow-up studies on disease-associated genomic regions identified via GWAS in other human complex diseases.

There are several other examples that have demonstrated the importance of non-coding SVs in the etiology of sporadic neurodegenerative diseases in adulthood. The GGGGCC (G4C2) repeat expansion in C9ORF72 and Rep1 in SNCA have been extensively studied. Most recently, a massive hexanucleotide (GGGGCC) repeat expansion mutation in the C9orf72 gene has been linked to the majority of familial ALS, familial-FTD as well as some sporadic forms of FTD, and mixed ALS-FTD cases [54–56]. The molecular mechanism through which the expanded G4C2 hexanucleotide repeat in the C9orf72 gene exerts its pathogenic effect has been studied substantially and three different prototypes of pathogenic mechanisms have been demonstrated [57]: Loss of function of the gene containing the repeat (haploinsufficiency), toxic gain of property due to the expression of protein containing the repeat expansion (mutant protein), and the gain of RNA toxicity due to the production of RNA containing the G4C2 repeat expansion (mutant RNA)[55, 58, 59]. Another example for the contributory role of structural variants to neurodegenerative disease is SNCA-Rep1. Rep1, a highly polymorphic, complex microsatellite, which is located ~10Kb upstream of the SNCA gene and in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with 5’-SNCA LD block, was associated repeatedly with increased risk to develop late-onset PD [11, 30–33]. Using a luciferase reporter assay, humanized mouse model and human brain tissues, we correlated the genetic association with biological functions and demonstrated that Rep1 acts as a transcriptional regulator of the gene, with the risk allele associated with elevated levels of SNCA-mRNA [24, 34–37]. In addition, using phylogenetic analysis based on phased sequence data, we identified a variable intronic poly-T, rs10524523 (‘523’) in the TOMM40 gene that is associated with risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s Disease (LOAD) and age of onset for LOAD in Caucasian individuals[60, 61]. Analysis of phased sequence data from Africans and African Americans has shown that there are specific APOE-’523 haplotypes, associated with differential risk for LOAD that are common in these ethnicities but rare in Caucasians. These findings have profound implications for estimation of age-dependent risk for LOAD and have clinical implications for the design of LOAD prevention trials for mixed ethnic populations[62]. We also demonstrated using AD-affected and normal brain tissues and a luciferase reporter system that this highly-variable poly-T site regulates the transcripts levels of both TOMM40 and its neighboring gene, APOE [63].

Histones function in the regulation of gene expression, and histone modifications serve as good epigenetic indicators of chromatin state associated with gene activation or repression [64–66]. Histone H3 modifications are studied for epigenome profiling and their signals can guide the identification of gene-transcriptional elements, such as promoter and enhancers elements. In general, transcription start sites of actively transcribed genes are marked by trimethylated H3K4 (H3K4me3) and acetylated H3K27 (H3K27ac), and active enhancers can be identified by enrichments of both mono- methylated H3K4 (H3K4me1) and H3K27ac [64–66]. In this current study, the position of the highly polymorphic CT-rich region overlaps with the signature of an enhancer, i.e. a high H3K4me1 signal and a H3K27ac mark (although the later is relatively low). In addition, it has been suggested that SVs have regulatory functions in gene transcription[23–28]. Here, we showed that haplotype of this highly polymorphic SV affects the steady-state levels of SNCA-mRNA. Our expression results together with the epigenetic data showing that the highly polymorphic CT-rich region resides within the histone modification signal suggest that it acts as an enhancer element of transcription regulation. The molecular mechanism underlying the effect of this highly polymorphic CT-rich region on SNCA-mRNA levels warrants further investigation using biological systems and genome editing approaches that will provide direct evidence of its plausible role as an enhancer element of transcription and will characterize the regulatory effect of haplotype 3.

Bras et al. [17] recently found that the association of SNCA with DLB is distinct from the reported association of SNCA with PD. Comparison of the association region between PD and DLB, showed that the haplotype conferring risk was different in these two diseases and suggested that it may explain the different distribution of the LBs in the brain tissue, while LB are generally localized to brainstem in PD they have a more widespread distribution in DLB cases [17]. Consequently, the relation of the SNCA gene with the different diseases in the broader spectrum of synucleinopathies might represent a case of allelic heterogeneity and pleiotropy. Therefore, the relevance of this newly-identified set of CT-rich haplotypes to other LB-related disorders including PD and DLB is of great interest.

Supplementary Material

Table 5.

Variants found by Phased Sequencing of 521 bp CT-rich Region

| Variant Name |

Position in 521 bp Region |

Position on Chr4 (HG19) |

Variant Type |

Reference Allele | Variant Allele | Number of Variants Found |

Variant Allele Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2298728 | 6 | 90,742,815 | SNP | C | T | 15 | 0.08 |

| rs112597569 | 106 | 90,742,715 | Deletion | TAC | - | 59 | 0.31 |

| rs35897584 | 129 | 90,742,692 | SNP | T | C | 15 | 0.08 |

| rs17016251 | 182 | 90,742,639 | SNP | C | G | 62 | 0.33 |

| rs79624097 | 332 | 90,742,489 | SNP | C | T | 74 | 0.39 |

| rs142125351 | 346 | 90,742,476 | Insertion | - | ACTTTCTTTCCTTTCTTTCTTT | 136 | 0.72 |

| rs145649402 | 359 | 90,742,462 | Deletion | TCCTTTCTCCCTTC CTTCCTTCCT |

- | 62 | 0.33 |

| rs386677149 | 364 | 90,742,457 | MNP | TC | CT | 59 | 0.31 |

| Novel | 382 | 90,742,439 | Insertion | - | CCCTTTCTTTCTTTCTCTTTTTTCTTTCTT GCTTCCTTCCTTCCTTCTTTCCTTTTCTTT CTTTTCCCTTCCTTCCT |

59 | 0.31 |

N=95 samples, 188 fully sequenced haplotypes

Research in Context.

Systematic review: We used standard sources of biomedical literature, genome browsers, and information learned at scientific meetings and through contacts with colleagues to search, review and evaluate accumulated knowledge regarding genetic associations of the SNCA gene with Lewy-body (LB) related disorders and the role of structural variants (SVs) in human complex-diseases.

Interpretation: Our study represents a significant advancement towards the identification of causal/functional SVs and haplotypes in SNCA locus that underlie the mixed pathologies of LB and AD, and highlights the importance of the individual’s diplotypes in the etiology of complex neurodegenerative phenotypes in general, and in particular on the spectrum of AD and PD.

Future directions: We will next determine the relevance of this CT-rich haplotype to other LB-spectrum disorders, and validate its regulatory effect on SNCA expression and LB formation using biological system and genome-editing approaches.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH/NINDS) [R01 NS085011 to O.C.]. We thank the Kathleen Price Bryan Brain Bank (KPBBB) at Duke University for providing us with the brain tissues.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pankratz N, Wilk JB, Latourelle JC, DeStefano AL, Halter C, Pugh EW, et al. Genomewide association study for susceptibility genes contributing to familial Parkinson disease. Hum Genet. 2009;124:593–605. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0582-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myhre R, Toft M, Kachergus J, Hulihan MM, Aasly JO, Klungland H, et al. Multiple alpha-synuclein gene polymorphisms are associated with Parkinson’s disease in a Norwegian population. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118:320–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross OA, Gosal D, Stone JT, Lincoln SJ, Heckman MG, Irvine GB, et al. Familial genes in sporadic disease: common variants of alpha-synuclein gene associate with Parkinson’s disease. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pals P, Lincoln S, Manning J, Heckman M, Skipper L, Hulihan M, et al. alpha-Synuclein promoter confers susceptibility to Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:591–595. doi: 10.1002/ana.20268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueller JC, Fuchs J, Hofer A, Zimprich A, Lichtner P, Illig T, et al. Multiple regions of alpha-synuclein are associated with Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:535–541. doi: 10.1002/ana.20438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizuta I, Satake W, Nakabayashi Y, Ito C, Suzuki S, Momose Y, et al. Multiple candidate gene analysis identifies alpha-synuclein as a susceptibility gene for sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:1151–1158. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winkler S, Hagenah J, Lincoln S, Heckman M, Haugarvoll K, Lohmann-Hedrich K, et al. {alpha}-Synuclein and Parkinson disease susceptibility. Neurology. 2007 doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000275524.15125.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satake W, Nakabayashi Y, Mizuta I, Hirota Y, Ito C, Kubo M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies common variants at four loci as genetic risk factors for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1303–1307. doi: 10.1038/ng.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon-Sanchez J, Schulte C, Bras JM, Sharma M, Gibbs JR, Berg D, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals genetic risk underlying Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1308–1312. doi: 10.1038/ng.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards TL, Scott WK, Almonte C, Burt A, Powell EH, Beecham GW, et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Confirms SNPs in SNCA and the MAPT Region as Common Risk Factors for Parkinson Disease. Ann Hum Genet. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00560.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maraganore DM, de Andrade M, Elbaz A, Farrer MJ, Ioannidis JP, Kruger R, et al. Collaborative analysis of alpha-synuclein gene promoter variability and Parkinson disease. Jama. 2006;296:661–670. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spencer CC, Plagnol V, Strange A, Gardner M, Paisan-Ruiz C, Band G, et al. Dissection of the genetics of Parkinson’s disease identifies an additional association 5’ of SNCA and multiple associated haplotypes at 17q21. Hum Mol Genet. 20:345–353. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon-Sanchez J, van Hilten JJ, van de Warrenburg B, Post B, Berendse HW, Arepalli S, et al. Genome-wide association study confirms extant PD risk loci among the Dutch. Eur J Hum Genet. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mata IF, Shi M, Agarwal P, Chung KA, Edwards KL, Factor SA, et al. SNCA variant associated with Parkinson disease and plasma alpha-synuclein level. Arch Neurol. 67:1350–1356. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Chalabi A, Durr A, Wood NW, Parkinson MH, Camuzat A, Hulot JS, et al. Genetic variants of the alpha-synuclein gene SNCA are associated with multiple system atrophy. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scholz SW, Houlden H, Schulte C, Sharma M, Li A, Berg D, et al. SNCA variants are associated with increased risk for multiple system atrophy. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:610–614. doi: 10.1002/ana.21685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bras J, Guerreiro R, Darwent L, Parkkinen L, Ansorge O, Escott-Price V, et al. Genetic analysis implicates APOE, SNCA and suggests lysosomal dysfunction in the etiology of dementia with Lewy bodies. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6139–6146. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linnertz C, Lutz MW, Ervin JF, Allen J, Miller NR, Welsh-Bohmer KA, et al. The genetic contributions of SNCA and LRRK2 genes to Lewy Body pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:4814–4821. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Consortium EP. The ENCODE (ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements) Project. Science. 2004;306:636–640. doi: 10.1126/science.1105136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Consortium EP, Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, Guigo R, Gingeras TR, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Souza N. The ENCODE project. Nature methods. 2012;9:1046. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pennisi E. Genomics. ENCODE project writes eulogy for junk DNA. Science. 2012;337:1159, 61. doi: 10.1126/science.337.6099.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akai J, Kimura A, Hata RI. Transcriptional regulation of the human type I collagen alpha2 (COL1A2) gene by the combination of two dinucleotide repeats. Gene. 1999;239:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiba-Falek O, Nussbaum RL. Effect of allelic variation at the NACP-Rep1 repeat upstream of the alpha-synuclein gene (SNCA) on transcription in a cell culture luciferase reporter system. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:3101–3109. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.26.3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okladnova O, Syagailo YV, Tranitz M, Stober G, Riederer P, Mossner R, et al. A promoter-associated polymorphic repeat modulates PAX-6 expression in human brain. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1998;248:402–405. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peters DG, Kassam A, St Jean PL, Yonas H, Ferrell RE. Functional polymorphism in the matrix metalloproteinase-9 promoter as a potential risk factor for intracranial aneurysm. Stroke. 1999;30:2612–2616. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Searle S, Blackwell JM. Evidence for a functional repeat polymorphism in the promoter of the human NRAMP1 gene that correlates with autoimmune versus infectious disease susceptibility. Journal of medical genetics. 1999;36:295–299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimajiri S, Arima N, Tanimoto A, Murata Y, Hamada T, Wang KY, et al. Shortened microsatellite d(CA)21 sequence down-regulates promoter activity of matrix metalloproteinase 9 gene. FEBS Lett. 1999;455:70–74. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00863-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hefferon TW, Groman JD, Yurk CE, Cutting GR. A variable dinucleotide repeat in the CFTR gene contributes to phenotype diversity by forming RNA secondary structures that alter splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3504–3509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400182101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farrer M, Maraganore DM, Lockhart P, Singleton A, Lesnick TG, de Andrade M, et al. alpha-Synuclein gene haplotypes are associated with Parkinson’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1847–1851. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.17.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Izumi Y, Morino H, Oda M, Maruyama H, Udaka F, Kameyama M, et al. Genetic studies in Parkinson’s disease with an alpha-synuclein/NACP gene polymorphism in Japan. Neurosci Lett. 2001;300:125–127. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01557-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kruger R, Vieira-Saecker AM, Kuhn W, Berg D, Muller T, Kuhnl N, et al. Increased susceptibility to sporadic Parkinson’s disease by a certain combined alpha-synuclein/apolipoprotein E genotype. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:611–617. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199905)45:5<611::aid-ana9>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan EK, Matsuura T, Nagamitsu S, Khajavi M, Jankovic J, Ashizawa T. Polymorphism of NACP-Rep1 in Parkinson’s disease: an etiologic link with essential tremor? Neurology. 2000;54:1195–1198. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.5.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiba-Falek O, Kowalak JA, Smulson ME, Nussbaum RL. Regulation of alpha-synuclein expression by poly (ADP ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) binding to the NACP-Rep1 polymorphic site upstream of the SNCA gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:478–492. doi: 10.1086/428655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiba-Falek O, Touchman JW, Nussbaum RL. Functional analysis of intra-allelic variation at NACP-Rep1 in the alpha-synuclein gene. Hum Genet. 2003;113:426–431. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cronin KD, Ge D, Manninger P, Linnertz C, Rossoshek A, Orrison BM, et al. Expansion of the Parkinson disease-associated SNCA-Rep1 allele upregulates human alpha-synuclein in transgenic mouse brain. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:3274–3285. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linnertz C, Saucier L, Ge D, Cronin KD, Burke JR, Browndyke JN, et al. Genetic regulation of alpha-synuclein mRNA expression in various human brain tissues. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hulette C, Mirra S, Wilkinson W, Heyman A, Fillenbaum G, Clark C. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part IX. A prospective cliniconeuropathologic study of Parkinson’s features in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1995;45:1991–1995. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.11.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parkkinen L, Soininen H, Alafuzoff I. Regional distribution of alpha-synuclein pathology in unimpaired aging and Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:363–367. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hansen LA. The Lewy body variant of Alzheimer disease. Journal of neural transmission Supplementum. 1997;51:83–93. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6846-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta neuropathologica. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mirra SS. The CERAD neuropathology protocol and consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a commentary. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:S91–S94. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part IIStandardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–486. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKeith IG, Perry EK, Perry RH. Report of the second dementia with Lewy body international workshop: diagnosis treatment. Consortium on Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Neurology. 1999;53:902–905. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–1872. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiba-Falek O, Lopez GJ, Nussbaum RL. Levels of alpha-synuclein mRNA in sporadic Parkinson disease patients. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1703–1708. doi: 10.1002/mds.21007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods (San Diego, Calif. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bengtsson M, Stahlberg A, Rorsman P, Kubista M. Gene expression profiling in single cells from the pancreatic islets of Langerhans reveals lognormal distribution of mRNA levels. Genome Res. 2005;15:1388–1392. doi: 10.1101/gr.3820805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frazer KA, Murray SS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Human genetic variation and its contribution to complex traits. Nature reviews Genetics. 2009;10:241–251. doi: 10.1038/nrg2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Montgomery SB, Goode DL, Kvikstad E, Albers CA, Zhang ZD, Mu XJ, et al. The origin, evolution, and functional impact of short insertion-deletion variants identified in 179 human genomes. Genome research. 2013;23:749–761. doi: 10.1101/gr.148718.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Willems T, Gymrek M, Highnam G, Genomes Project C, Mittelman D, Erlich Y. The landscape of human STR variation. Genome research. 2014;24:1894–1904. doi: 10.1101/gr.177774.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chaisson MJ, Huddleston J, Dennis MY, Sudmant PH, Malig M, Hormozdiari F, et al. Resolving the complexity of the human genome using single-molecule sequencing. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tewhey R, Bansal V, Torkamani A, Topol EJ, Schork NJ. The importance of phase information for human genomics. Nature reviews Genetics. 2011;12:215–223. doi: 10.1038/nrg2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeJesus-Hernandez M, Mackenzie IR, Boeve BF, Boxer AL, Baker M, Rutherford NJ, et al. Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p–linked FTD and ALS. Neuron. 2011;72:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Haeusler AR, Donnelly CJ, Periz G, Simko EA, Shaw PG, Kim MS, et al. C9orf72 nucleotide repeat structures initiate molecular cascades of disease. Nature. 2014;507:195–200. doi: 10.1038/nature13124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renton AE, Majounie E, Waite A, Simon-Sanchez J, Rollinson S, Gibbs JR, et al. A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron. 2011;72:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Verma A. Tale of two diseases: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology India. 2014;62:347–351. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.141174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Y, Yu JT, Sun FR, Ou JR, Qu SB, Tan L. The clinical and pathological phenotypes of frontotemporal dementia with C9ORF72 mutations. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2013;335:26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ling SC, Polymenidou M, Cleveland DW. Converging mechanisms in ALS and FTD: disrupted RNA and protein homeostasis. Neuron. 2013;79:416–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crenshaw DG, Gottschalk WK, Lutz MW, Grossman I, Saunders AM, Burke JR, et al. Using genetics to enable studies on the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2013;93:177–185. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roses AD, Lutz MW, Amrine-Madsen H, Saunders AM, Crenshaw DG, Sundseth SS, et al. A TOMM40 variable-length polymorphism predicts the age of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. The pharmacogenomics journal. 2010;10:375–384. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roses AD, Lutz MW, Saunders AM, Goldgaber D, Saul R, Sundseth SS, et al. African-American TOMM40’523-APOE haplotypes are admixture of West African and Caucasian alleles. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2014;10:592–601. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Linnertz C, Anderson L, Gottschalk W, Crenshaw D, Lutz MW, Allen J, et al. The cis-regulatory effect of an Alzheimer’s disease-associated poly-T locus on expression of TOMM40 and apolipoprotein E genes. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2014;10:541–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.08.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kimura H. Histone modifications for human epigenome analysis. Journal of human genetics. 2013;58:439–445. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2013.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith E, Shilatifard A. Enhancer biology and enhanceropathies. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2014;21:210–219. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Keating ST, El-Osta A. Transcriptional regulation by the Set7 lysine methyltransferase. Epigenetics : official journal of the DNA Methylation Society. 2013;8:361–372. doi: 10.4161/epi.24234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.