Abstract

The aim of the study was to establish the extended high frequency thresholds (EHF) of school-age children with no hearing complaints. The study was conducted on 50 children aged 8 to 12 years with pure tone thresholds (0.5, 1 and 2 kHz) of 15 dB HL or less, with normal speech discrimination and tympanometry and with the presence of contralateral acoustic reflexes of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz. The children were tested for EHF at frequencies of 9, 10, 11.2, 12.5, 14 and 16 kHz. No significant differences were found between the right and left ear for female and male groups. The results allowed us to group the children into a single sample with mean thresholds (dB) of 8.6 (9 kHz), 6.2 (10 kHz), 8.2 (11.2 kHz), 7.1 (12.5 kHz), 0.4 (14 kHz), and -3.6 (16 kHz). We conclude that, for school-age children, the extended EHF below 15 dBHL could be used as an indication of normal hearing sensitivity.

Key words: hearing, high-frequency audiometry, audiometry, threshold, age, child.

Introduction

Auditory sensitivity can be routinely measured at frequencies between 0.25 and 8 kHz. However, over the last few years, the assessment of hearing in the frequency range of 9 to 20 kHz, a procedure known as Extended High Frequency Audiometry (EHFA) or High Frequency Audiometry (HFA), has proved to be a promising tool for the early diagnosis of many hearing disorders.

Several studies have pointed out the importance of EHFA for an early diagnosis of hearing disorders of different etiology, such as aging, exposure to ototoxic drugs and to occupational noise, sequels of otitis media, monitoring of hearing in persons with renal failure, assessment of disorders of hearing processing, and investigation of hearing impairment among the relatives of patients with hearing loss of genetic origin.1–3

Hearing loss in childhood may impair or delay the full acquisition and development of language in any modality. For adequate acoustic perception, it is of primordial importance for an individual to be able to detect sounds in the range of 5 to 9 kHz since these sounds guarantee a good part of speech intelligibility by favoring consonant discrimination and speech recognition. In the presence of hearing loss in this frequency band, people may have difficulty in distinguishing the noise signal, with a consequent impairment of speech intelligibility in noisy environments.4–6

Speech intelligibility is very important for the acquisition and development of language, and studies on children with normal hearing have shown evidence of excellent hearing sensitivity for high frequency sounds.7

A number of studies have investigated the extended high frequency hearing threshold increase in children with a history of recurrent otitis and alterations in auditory processing. The results of these studies have suggested that the extended high frequency hearing loss in children may be due to a significant history of otitis media, since the prolongation of this infection can lead to the diffusion of toxins through the oval window membrane in the base of the cochlea.8–10 Also, there is an increase in sensitivity to extended high frequency sounds in school-age children with altered hearing processing compared to children with normal hearing processing.4

Although these studies have also investigated the extended high frequency threshold in normative control groups of children, the age range of the subjects varies widely in the various reports, thus compromising a comparison of the parameters proposed as reference.

It is known that a good hearing sensitivity for frequencies in the range of 5 to 9 kHz is important for the understanding of speech, and sensory deprivation during the phase of acquisition of this system may have negative consequences. The study of the relationahip between extended high frequency hearing threshold among children exposed to ototoxic medications with a history of recurrent otitis, and with altered hearing processing, among other variables, is of fundamental importance as a tool to be used for an early diagnosis of alterations in hearing threshold. However, in order to propose some reference standard, more research is needed to establish the extended high frequency hearing threshold for children with no hearing complaints. The objective of the present study was to establish the hearing thresholds of extended high frequency of school-age children with no hearing complaints.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospital, Faculty of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Brazil (n. 3082/2007). Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects responsible for the children participating in the study.

The study sample consisted of 50 children, 31 girls and 19 boys aged 8–12 years (mean=10.1 years) who fulfilled the inclusion criteria presented below. The study was conducted at the Audiology Clinic of the Speech Therapy Course, School of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Brazil, from February to July 2008.

Inclusion criteria

Subjects were included in the study if they presented no hearing complications and the following characteristics in both ears: i) mean hearing threshold up to 15 dB HL for frequencies of 0.5, 1 and 2 kHz;11 and ii) type A tympanometric curve with the presence of contralateral acoustic reflexes at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz.12 Twenty-three subjects were excluded from the sample.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were: clinically overt hearing loss and/or prolonged exposure to noise and/or a history of ototoxic medications.

Hearing evaluation

All procedures for hearing evaluation were conducted in a sound-treated room according to ISO 8253-1.50 standards. A clinical audiometer (Unity; Siemens) was used for the study with Sennheiser HDA 200 headphones (ISO 389-5; ISO 389-8 and IEC 60645-1). The headphone calibration was carried out using the automated procedure of the audiometer. Conventional audiometry was determined for octave frequencies of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8 kHz, and HFA was determined for frequencies of 9, 10, 11, 12, 14 and 16 kHz. Tympanometry and acoustic reflex measures were determined using an Interacoustics AZ-7 instrument with TDH 39P headphones. For conventional and extended high frequency audiometry, the headphones were positioned by the examiner and the child was instructed to raise an arm whenever he heard the auditory stimulus.

The pure tone air-conduction threshold was determined using the descending technique at 10 dB intervals until the point where the child no longer responded to the sound. Starting at that intensity, the ascending technique was used at 5 dB intervals until the child started to hear again. The hearing threshold was established for 50% of the responses obtained at the different frequencies studied.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed statistically using the Graph Pad Instat software, version 3.0 for Windows 95. Repeated Measures ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni multiple comparisons post-test test, and the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn multiple comparisons post-test were used to compare the EHFA thresholds. The Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn multiple comparisons post-test was used to analyze threshold variation along the frequencies. P<0.05 was considered significant and significant values are marked with an asterisk.

Results

Tables 1 and 2 present the values of the statistical tests applied to compare extended high frequency hearing thresholds according to ear (right and left) and gender variables. No significant differences were found between the right and left ear for the female and male groups.

Table 1. Descriptive analysis of the comparison of extended high frequency hearing thresholds according to ear (right and left) in females (n=31) for frequencies of 9, 10, 11.2, 12.5, 14 and 16 kHz.

| Frequency (ear) | Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum | CI <95% | CI >95% | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 kHz (RE) | 8.71 | 5.47 | 10 | 0 | 20 | 6.7 | 10.72 | >0.05 |

| 9 kHz (LE) | 7.1 | 6.55 | 10 | −5 | 15 | 4.7 | 9.5 | |

| 10 kHz (RE) | 6.13 | 8.54 | 5 | −5 | 30 | 3 | 9.26 | >0.05 |

| 10 kHz (LE) | 3.39 | 8 | 0 | −10 | 25 | 0.45 | 6.32 | |

| 11.2 kHz (RE) | 6.94 | 6.67 | 5 | −5 | 20 | 4.5 | 9.38 | >0.05 |

| 11.2 kHz (LE) | 6.45 | 7.77 | 5 | −5 | 25 | 3.6 | 9.3 | |

| 12.5 kHz (RE) | 6.45 | 6.73 | 5 | −5 | 20 | 3.98 | 8.92 | >0.05 |

| 12.5 kHz (LE) | 6.29 | 7.1 | 5 | −5 | 20 | 3.7 | 8.88 | |

| 14 kHz (RE) | −0.48 | 7.68 | 0 | -10 | 20 | -3.3 | 2.33 | >0.05 |

| 14 kHz (LE) | −1.77 | 6.78 | −5 | −10 | 10 | −4.26 | 0.71 | |

| 16 kHz (RE) | −6.13 | 4.78 | −10 | −10 | 5 | −7.88 | −4.38 | >0.05 |

| 16 kHz (LE) | −6.94 | 6.15 | −10 | −10 | 15 | −9.19 | −4.68 |

RE, right ear; LE, left ear; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

Table 2. Descriptive analysis of the comparison of extended high frequency hearing thresholds according to ear (right and left) in males (n=19) for frequencies of 9, 10, 11.2, 12.5, 14 and 16 kHz.

| Frequency (ear) | Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum | CI <95% | CI >95% | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 kHz (RE) | 10.79 | 9.61 | 10 | −5 | 30 | 6.16 | 15.42 | >0.05 |

| 9 kHz (LE) | 8.68 | 9.41 | 10 | −10 | 25 | 4.15 | 13.22 | |

| 10 kHz (RE) | 10.53 | 8.96 | 10 | −5 | 30 | 6.21 | 14.85 | >0.05 |

| 10 kHz (LE) | 6.58 | 8.17 | 5 | −5 | 25 | 2.64 | 10.52 | |

| 11.2 kHz (RE) | 13.16 | 10.17 | 10 | 0 | 35 | 8.26 | 18.06 | >0.05 |

| 11.2 kHz (LE) | 8.16 | 6.06 | 10 | 0 | 20 | 5.24 | 11.08 | |

| 12.5 kHz (RE) | 10 | 11.3 | 10 | −10 | 30 | 4.55 | 15.45 | >0.05 |

| 12.5 kHz (LE) | 6.32 | 8.14 | 5 | −10 | 25 | 2.39 | 10.24 | |

| 14 kHz (RE) | 4.47 | 11.77 | 5 | −10 | 25 | −1.2 | 10.15 | >0.05 |

| 14 kHz (LE) | 1.32 | 8.64 | 0 | −10 | 20 | −2.85 | 5.48 | |

| 16 kHz (RE) | 1.58 | 14.63 | −5 | −10 | 35 | −5.47 | 8.63 | >0.05 |

| 16 kHz (LE) | 1.05 | 13.29 | 0 | −10 | 30 | −5.35 | 7.46 |

RE, right ear; LE, left ear; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval.

Table 3 presents the values of the statistical tests applied to compare high frequency hearing thresholds between genders for the frequencies of 9, 10, 11.2, 12.5, 14 and 16k Hz. A significant difference was observed at 16 kHz between females and males, with high average thresholds for the boys. No significant differences were seen for the other frequencies.

Table 3. Descriptive analysis of extended high frequency hearing thresholds (dBHL) and results of the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn multiple comparisons post-test for gender comparison (n=31 females and 19 males) for frequencies of 9, 10, 11.2, 12.5, 14 and 16 kHz.

| Frequency (ear) | Mean | SD | Median | Minimum | Maximum | CI <95% | CI >95% | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 kHz (F) | 7.9 | 6.04 | 10 | −5 | 20 | 6.37 | 9.44 | >0.05 |

| 9 kHz (M) | 9.74 | 9.44 | 10 | −10 | 30 | 6.63 | 12.84 | |

| 10 kHz (F) | 4.76 | 8.32 | 5 | −10 | 30 | 2.65 | 6.87 | >0.05 |

| 10 kHz (M) | 8.55 | 8.69 | 5 | −5 | 30 | 5.69 | 11.41 | |

| 11.2 kHz (F) | 6.69 | 7.18 | 5 | −5 | 25 | 4.87 | 8.52 | >0.05 |

| 11.2 kHz (M) | 10.66 | 8.64 | 10 | 0 | 35 | 7.82 | 13.5 | |

| 12.5 kHz (F) | 6.37 | 6.85 | 5 | −5 | 20 | 4.63 | 8.11 | >0.05 |

| 12.5 kHz (M) | 8.16 | 9.89 | 5 | −10 | 30 | 4.9 | 11.41 | |

| 14 kHz (F) | -1.13 | 7.21 | 0 | −10 | 20 | -2.96 | 0.7 | >0.05 |

| 14 kHz (M) | 2.9 | 10.31 | 0 | −10 | 25 | −4.5 | 6.29 | |

| 16 kHz (F) | −6.53 | 5.48 | −10 | −10 | 15 | −7.92 | −5.14 | <0.05* |

| 16 kHz (M) | 1.32 | 13.79 | −5 | −10 | 35 | −3.22 | 5.85 |

F, female; M, male; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval;

significant difference.

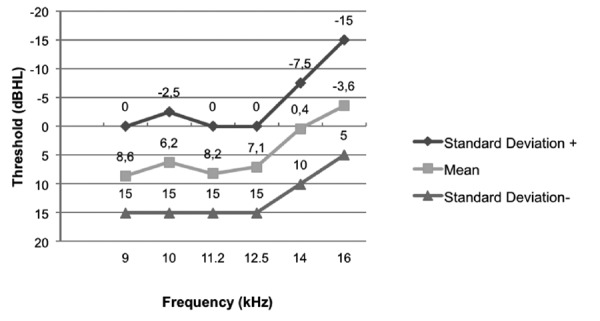

The mean and standard deviation (systematic error of 2.5 dBHL) data of extended high frequency threshold (dBHL) for frequencies of 9,10, 11.2, 12.5, 14 and 16 kHz in school-age children with no hearing complaints (n=50 children) are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean and standard deviation (systematic error of 2.5 dBHL) data of extended high frequency threshold (dBHL) for frequencies of 9, 10, 11.2, 12.5, 14 and 16 kHz in school-age children with no hearing complaints (n=50 children).

Discussion

The normal hearing standard thresholds for children13 and adults14 have been well established for frequencies of 0.25 to 8 kHz. However, in the evaluation of high frequencies, there still is no consensus in the specialized literature about what should be considered normal for children or adults.15–17 Some investigators have adopted the same normal standard as used in conventional audiometry in order to determine alterations of the threshold for frequencies above 8 kHz, whereby the normal value expected would be a threshold of up to 15 dB HL for children and 25 dB HL for adults.3

In children, some obstacles have been encountered in the comparison of the results in the literature, since the frequencies investigated, the age range studied and the criteria for subject inclusion were not always the same.1,7,15–22 Some authors have included in their studies children with tonal thresholds for conventional frequencies up to 15 dB HL,15 others have included thresholds up to 25 dB HL,2,18 and still others have used as an inclusion criterion a threshold of up to 20 dB HL for frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz.4

Another factor that compromised comparison with other studies was that some determine the extended high frequency hearing threshold in dB SPL according to the audiometer used.1,4,16,20,21

There was no significant difference in hearing thresholds between ears in girls and boys, as also reported in previous studies.2,4,18,23 In this study, these findings suggest that the average hearing thresholds were similar for right and left ears for all frequencies investigated in both genders.

The standard deviations were high in the population studied, a fact that may be explained by the methodology used for hearing assessment, since the exam was carried out with variation in intensity using 5 dBHL steps. To reduce the standard deviation, the ideal would be to carry out the frequency procedure using 1 dB steps, but this methodology would be difficult to use in clinical routine due to the time required, with consequent fatigue of the subject evaluated and possible impairment of the reliability of the results.2 One way to avoid this situation would be to use only frequencies of 10kHz, 12.5kHz and 16kHz and a 2 dB attenuator step, since the frequency resolution of 1 kHz is unnecessarily fine. In this study, these data were corrected by 2.5 dB steps.

Comparison of high frequency hearing thresholds between genders for the frequencies of 9, 10, 11.2, 12.5, 14 and 16 kHz revealed a significant difference at 16 kHz, with high average thresholds for the boys. No significant differences were seen for the other frequencies. As the sample size is small, further controlled studies are needed in order to verify that the differences at 16kHZ are significant for the whole population of children. In the literature, female gender presented a better threshold in the adult population1,18,19 and studies conducted on age ranges similar to that of this study did not mention this variable.7–9,15,16

Analysis of the mean values for the population investigated (Figure 1) showed that the thresholds did not exceed 10 dBHL.2,18,23 There was an improvement in hearing thresholds starting at 14 kHz, a common characteristic for this young age range.4,18,23 The best hearing sensitivity is found in infants, children and adolescents. A loss of hearing sensitivity over the frequency range of 15-18kHz starts around 20 years of age.7,16,20

The normal hearing standard thresholds established for children for frequencies of 0.25 to 8 kHz is expected to be up to 15 dB HL. The same normal standard used in conventional audiometry would be used as the limit of normal hearing threshold at standard extended high frequencies. The data of this study can guide the professional during the audiologic follow up of children and youngsters considered to be at risk, such as those exposed to ototoxic medications, with a history of recurrent otitis media, and with learning complaints.

Conclusions

For school-age children, the extended high frequency hearing thresholds below 15 dBHL could be used as an indication of normal hearing sensitivity.

Acknowledgments:

we gratefully acknowledge the doctors and audiologists of the University Hospital of the Faculty of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Brazil, for their cooperation. This work was supported by FAPESP - Brazil.

References

- 1.Mota Marmede Carvallo R, Koga MC, de Carvalho M, Ishida IM. High frequency thresholds in adults with no auditory complaints. ACTA ORL/Técn Otorrinolaringol. 2007;25:62–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferreira Mde S, de Almeida K, Atherino CC. Audibility threshold for high frequencies in children with medical history of multiple episodes of bilateral secretory otitis media. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;73:231–8. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31071-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crepaldi de Almeida EO, Umeoka WG, Viera RC, de Moraes F. High frequency audiometric study in cancer-cured patients treated with cisplatin. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;74:382–90. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30572-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramos CS, Pereira LD. Auditory processing and high frequency audiometry in students of São Paulo. Pró-Fono R Atual Cient. 2005;17:153–64. doi: 10.1590/s0104-56872005000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boothroyd A, Erickson FN, Medwetsky L. The hearing aid input: a phonemic approach to assessing the spectral distribution of speech. Ear Hear. 1994;15:432–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boothroyd A, Medwetsky L. Spectral distribution of /s/ and the frequency response of hearing aids. Ear Hear. 1992;13:150–7. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199206000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trehub SE, Schneider BA, Morrongiello BA, Thorpe LA. Developmental changes in high frequency sensitivity. Audiology. 1989;28:241–9. doi: 10.3109/00206098909081629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Margolis RH, Hunter LL, Rykken JR, Giebink GS. Effects of otitis media on extended high-frequency hearing in children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102:1–5. doi: 10.1177/000348949310200101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter LL, Margolis RH, Rykken JR, Le CT, Daly KA, Giebink GS. High frequency hearing loss associated with otitis media. Ear Hear. 1996;17:1–11. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199602000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laitila P, Karma P, Sipilä M, Manninen M, Rakho T. Extended high frequency hearing and history of acute otitis media in 14-year-old children in Finland. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1997;529:27–9. doi: 10.3109/00016489709124072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roeser RJ. Rio de Janeiro: Revinter; 2001. Roeser's audiology desk reference. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jerger J. Clinical experience with impedance audiometry. Arch Otolaryngol. 1970;92:311–24. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1970.04310040005002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Northern JL, Downs MP. 4th ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1991. Hearing in children. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davis H, Silverman RS. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston;; 1870. Hearing and deafness. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shechter MA, Fausti SA, Rappaport BZ, Frey RH. Age categorization of high-frequency auditory threshold data. J Acoust Soc Am. 1986;79:767–71. doi: 10.1121/1.393466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stelmachowicz PG, Beauchaine KA, Kalberer A, Jesteadt W. Normative thresholds in the 8- to 20-kHz range as a function of age. J Acoustic Soc Am. 1989;86:1384–91. doi: 10.1121/1.398698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahyeb DR, Costa Filho AO, Alvarenga KF. High-frequency audiometry: study with normal audiological subjects. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;69:93–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedalini ME, Sanchez TG, Dántonio W. Threshold measure at extended high frequency audiometry in normal listeners from 4 to 60 years old. Pró-Fono R Atual Cient. 2000;12:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monteiro de Castro Silva I, Feitosa MA. High-frequency audiometry in young and older adults when conventional audiometry is normal. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;72:665–72. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31024-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reuter W, Schönfeld U, Mansmann U, Fischer R, Gross M. Extended high frequency audiometry in pre-school children. Audiology. 1998;37:285–94. doi: 10.3109/00206099809072982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azevedo LL, Iorio MCM. Study of high-frequency thresholds in normal hearing people between 12 and 15 years old. Acta Awho. 1999;18:78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Sá LC, Lima MA, Tomita S, Frota SM, Santos Gde A, Garcia TR. Analysis of high frequency auditory thresholds in individuals aged between 18 and 29 years with no otological complaints. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;73:215–25. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31069-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groh D, Pelanova J, Jilek M, Popelar J, Kabeka Z, Syka J. Changes in otoacoustic emissions and high-frequency hearing thresholds in children and adolescents. Hear Res. 2006;212:90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]