Elevational changes in temperature and carbon dioxide can be used to predict the likely responses of plants to climate change. However, plant species often exhibit contrasting photosynthetic and morphological responses to altitude. We investigated the photosynthetic responses of plants with different leaf morphologies and growth habits to increased elevation. At high elevations, plants with schlerophyllous leaves that represent a large structural investment are more likely to be positively affected by rising carbon dioxide than species with a lower investment in foliage.

Keywords: Elevation, mesophyll conductance, partial pressure of CO2, photosynthesis, Quercus spinosa, Rumex dentatus, Salix atopantha, stomatal conductance

Abstract

Plant growth at high elevations necessitates physiological and morphological plasticity to enable photosynthesis (A) under conditions of reduced temperature, increased radiation and the lower partial pressure of atmospheric gases, in particular carbon dioxide (pCO2). Previous studies have observed a wide range of responses to elevation in plant species depending on their adaptation to temperature, elevational range and growth habit. Here, we investigated the effect of an increase in elevation from 2500 to 3500 m above sea level (a.s.l.) on three montane species with contrasting growth habits and leaf economic strategies. While all of the species showed identical increases in foliar δ13C, dark respiration and nitrogen concentration with elevation, contrasting leaf gas exchange and photosynthetic responses were observed between species with different leaf economic strategies. The deciduous shrub Salix atopantha and annual herb Rumex dentatus exhibited increased stomatal (Gs) and mesophyll (Gm) conductance and enhanced photosynthetic capacity at the higher elevation. However, evergreen Quercus spinosa displayed reduced conductance to CO2 that coincided with lower levels of photosynthetic carbon fixation at 3500 m a.s.l. The lower Gs and Gm values of evergreen species at higher elevations currently constrains their rates of A. Future rises in the atmospheric concentration of CO2 ([CO2]) will likely predominantly affect evergreen species with lower specific leaf areas (SLAs) and levels of Gm rather than deciduous species with higher SLA and Gm values. We argue that climate change may affect plant species that compose high-elevation ecosystems differently depending on phenotypic plasticity and adaptive traits affecting leaf economics, as rising [CO2] is likely to benefit evergreen species with thick sclerophyllous leaves.

Introduction

The adaptational responses of plants to alterations in temperature and the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) along elevational gradients have been used to infer the likely responses of vegetation to climatic changes in the past and future (e.g. Körner 2007; Kouwenberg et al. 2007; Bai et al. 2015). The partial pressure of all atmospheric gases declines with elevation, reducing the availability of CO2 for photosynthesis and oxygen for respiration, while lower temperatures and higher levels of radiation may decrease the activity of photosynthetic and metabolic enzymes (Gale 1972a; Miroslavov and Kravkina 1991; Allen and Ort 2001). Growth at high elevation, therefore, necessitates physiological and morphological adaptations to enable photosynthesis (e.g. Woodward 1986; Williams and Black 1993; Terashima et al. 1995; Cordell et al. 1998; Körner 2007; Feng et al. 2013). High-elevation ecosystems are often more sensitive to climatic change than those at sea level, as the influence of rising atmospheric temperature and carbon dioxide concentration ([CO2]) on photosynthesis becomes more pronounced with elevation (Gale 1972a, b, 1973; Terashima et al. 1995). Nonetheless, not all plant species respond in the same manner along elevational gradients, and comparatively little is known regarding the physiological and morphological adaptation of plants growing at high elevations >2500 m above sea level (a.s.l.). An understanding of the physiological and morphological processes that underpin photosynthesis and leaf gas exchange at high elevations may assist in our understanding of the likely impacts of future climate change on these high-elevation ecosystems.

In addition to physical changes to pCO2 and temperature, an increase in elevation may also be associated with fluctuations in soil type, wind speed, water availability and the quality/quantity of incident radiation (Körner 2007). These factors will all influence plant growth and photosynthesis (e.g. Körner and Cochrane 1985; Woodward 1986). The photosynthetic performance of a plant is determined by its capacity for the uptake and assimilation of CO2 (Farquhar et al. 1980); this is controlled by stomatal (Gs) and mesophyll conductance (Gm) to CO2, the carboxylation capacity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO) (Vcmax) and the maximum rate of electron transport for RuBP regeneration (Jmax) (e.g. Shi et al. 2006; Centritto et al. 2009; Haworth et al. 2011; Feng et al. 2013). Stomatal conductance frequently increases with elevation, possibly as a result of the lower availability of CO2 in the atmosphere necessitating increased rates of conductance to sustain adequate CO2 uptake (Körner et al. 1986; Woodward 1986). This enhanced Gs with elevation is often accompanied by increased stomatal density values and higher rates of transpirative water loss (Körner and Cochrane 1985; Woodward and Bazzaz 1988; Kouwenberg et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2014). The lower partial pressures of gases at high elevations will not only result in more rapid diffusion through the stomatal pore of CO2 but also water vapour, which when combined with the generally higher irradiances and drier atmosphere at high elevations will enhance the transpirative costs of growth at high elevation (Gale 1972a, b, 1973). However, these patterns of increased Gs are not universal, with species such as Quercus aquifolioides (Li et al. 2006; Feng et al. 2013), Q. guyavifolia (Hu et al. 2015) and Typha orientalis (Bai et al. 2015) exhibiting reduced Gs and stomatal density with elevation. Species with reduced Gs at high elevation may exploit the more rapid diffusion of CO2 at low partial pressures (Gale 1972a) by increasing rates of carboxylation of CO2 to maintain the diffusion gradient between the internal leaf and external atmosphere (Cordell et al. 1998; Shi et al. 2006) without incurring the additional transpirative costs associated with increased Gs and stomatal density (Haworth et al. 2015). However, lower temperatures at high elevation may also minimize the effect of increased diffusion of CO2 at lower partial pressures during the gaseous phase of CO2 transport (Körner 2007).

The concentration of CO2 inside the chloroplast envelope is directly related to stomatal and mesophyll conductance to the transport of CO2 (Loreto et al. 2009; Flexas et al. 2013). As a result, Gs and Gm often operate synchronously to determine photosynthesis (A) as a function of the total conductance to CO2 (Gtot) (Centritto et al. 2003; Hu et al. 2010; Lauteri et al. 2014). More rapid diffusion of CO2 at lower partial pressures may counteract the effect of reduced availability on gaseous transport of CO2 through the stomata to the spongy mesophyll (Gale 1972a), but this will not influence the transport of CO2 through the aqueous phase to the chloroplast (Loreto et al. 1994; Flexas et al. 2013). As such, the lower partial pressure of CO2 will have a significant impact on A, and Gm will play a significant role in determining the response of a plant species to growth at high elevation. It may be expected that an increase in elevation would induce a rise in Gm to ensure CO2 uptake at lower partial pressures; however, Gm is determined by a number of physical and biochemical factors (Warren 2007; Niinemets et al. 2009) that are also affected by elevation (Körner et al. 1979, 1986; Kogami et al. 2001; Feng et al. 2013). The specific leaf area (SLA) of temperate species tends to decrease with elevation, resulting in leaves with more closely packed cells (Friend and Pomeroy 1970; Friend et al. 1989; Li et al. 2013; Pan et al. 2013; Haworth and Raschi 2014) and lower Gm values (Kogami et al. 2001; Niinemets et al. 2009; Feng et al. 2013). For example, Polygonum cuspidatum exhibited a reduction in SLA and Gm over an elevation range of 10–2500 m (Kogami et al. 2001). This reduction in SLA with elevation is likely a result of increased incident radiation inducing a more compact leaf morphology (Niinemets 2001; Poorter et al. 2009). Increased elevation also resulted in a decrease of SLA and Gm values, but no change in Gs, in the tropical Hawaiian tree species Meterosideros polymorpha (Cordell et al. 1998). In contrast, the highland species Buddleja davidii that grows from 1200 to 3500 m a.s.l. exhibited no alteration of SLA, but a reduction in Gs alongside an increase in Gm with elevation that corresponded to enhanced Vcmax (Shi et al. 2006). This indicates the importance of the temperature to which a species is adapted and leaf economic strategy in determining the response to elevation (Hovenden and Vander Schoor 2004).

Photosynthesis rates decline with elevation due to lower partial pressures reducing the availability of CO2 (Gale 1972a; Körner and Diemer 1987) and diminished temperatures resulting in lower activity of photosynthetic enzymes (Fryer et al. 1998). The selective pressures exerted by lower temperatures and pCO2 may induce increased photosynthetic capacity (i.e. enhanced Vcmax and Jmax) at high elevation to enable sufficient CO2 uptake (Cordell et al. 1998; Shi et al. 2006; Feng et al. 2013). At higher elevations, greater Vcmax and Jmax are associated with increased leaf nitrogen and chlorophyll concentrations, but lower photosynthetic nitrogen use efficiency (PNUE) (Cordell et al. 1998; Kogami et al. 2001; Feng et al. 2013). Increased leaf nitrogen levels at higher elevations also commonly correspond to reduced SLA (Feng et al. 2013); conversely at sea level, SLA is often positively related to nitrogen concentration (Poorter et al. 1990). At high elevations, many species exhibit a reduction in leaf area (Kouwenberg et al. 2007), possibly as a response to increased levels of incident radiation that would increase leaf temperatures and transpiration rates through increased leaf to air vapour pressure deficit (Körner and Cochrane 1985). This shift in leaf area would affect the calculation of SLA (Poorter et al. 2009), and suggests that the temperature lapse rate and decline in pCO2 with elevation, and the selective pressures they exert induce differential adaptational responses to those observed at low elevation, and may therefore have different effects on plants with contrasting growth habits and leaf economic strategies.

Plants growing at high elevations of 2500–3500 m a.s.l. experience relatively low pCO2 in the range of 27.7–24.6 Pa in comparison with pCO2 of 38 Pa at sea level. The temperature lapse rate equates to an average decline in temperature of 5.5 °C with every 1000 m gained in elevation (Barry 2013). In this study, we aimed to characterize the physiological and morphological adaptations of three plant species with different growth habits: an evergreen tree (Q. spinosa), a deciduous shrub (Salix atopantha) and a herbaceous annual (Rumex dentatus). The responses to growth at high elevation of the three study species were also compared with those of Q. aquifolioides from the same habitat in an earlier investigation by Feng et al. (2013). To assess the adaptational responses of these plants to high elevations in the range of 2500–3500 m a.s.l., we conducted leaf gas exchange measurements and sampled leaves in the field to (i) analyse photosynthetic physiology at high elevations, (ii) characterize leaf gas exchange through quantification of stomatal and mesophyll conductance responses to CO2 and any diffusional limitation to photosynthesis, (iii) gauge the effect of reduced pCO2 and temperature on leaf economics and nitrogen concentration and (iv) evaluate the likely effect of future climate change in terms of rising pCO2 and temperature on mountainous species and ecosystems.

Methods

Plant material and study area

Three plant species with contrasting growth habits that grow at high elevations in north-western China were chosen for analysis. Quercus spinosa is a 6–10 m tall evergreen tree occurring in mountain regions of South East Asia over an elevation range of 1000–3500 m and over a range of 2000–3500 m in south-western China (Wu et al. 2011). Salix atopantha is a deciduous shrub 1–2 m in size, specific to western and south-western China occurring in mountainous regions at elevations of 2300–3500 m (Chen-Fu and Skvortsov 1998). Rumex dentatus is a 0.3–0.7 m tall annual herb that grows on moist slopes from sea level to high elevations (>3500 m a.s.l.) in Asia, North Africa and Europe (Kumar et al. 2005). It grows in mountainous regions at elevations of 1200–3600 m in south-western China (Shi and Ming 1987).

Populations of Q. spinosa, S. atopantha and R. dentatus at elevations of 2400 and 3500 m a.s.l. in the Wolong Reserve (south-eastern Tibetan-Qinghai area, Sichuan Province, China) (32°25′–32°53′N, 104°20′–104°41′E) were studied. The populations from the higher and lower elevations did not experience water stress and received full illumination with no shading. The leaves used for gas exchange measurements and collected for leaf economic traits, carbon isotope and nitrogen concentration analysis were at identical developmental stages (i.e. the youngest fully expanded leaf at the end of a branch). Field work was conducted from July to August 2010.

Gas exchange and fluorescence measurements

Leaf gas exchange and fluorescence parameters of the central leaf section were simultaneously measured using a LI-6400-40 leaf chamber fluorometer (LI-COR, Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) equipped with a 2-cm2 cuvette. One leaf was analysed from six plants for each species at each elevation. The concentration of atmospheric gases is constant with elevation; rather, it is the partial pressure of those gases that declines as elevation increases. All measurements were conducted at the same concentration of [CO2] but at the respective partial pressures of 2500 and 3500 m a.s.l. The LiCor Li6400 contains a barometric pressure sensor that allows for compensation of the effects of changes in partial pressure on measurements over a range of 65–115 kPa with an accuracy of and resolution of 0.002 kPa. Standard atmospheric pressure at sea level is 101.325 kPa, and at 3500 m a.s.l., atmospheric pressure is ∼70 kPa, indicating that our measurements were conducted within the operating range of the instrument. The measurements were made in situ between 9:00 and 15:00 at a saturating photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 1200 μmol m−2 s−1 for Q. spinosa, 1400 μmol m−2 s−1 for S. atopantha and 2000 μmol m−2 s−1 for R. dentatus at a CO2 concentration of 380 μmol mol−1. The saturating PPFD was determined by response curves of A to increasing PAR (Ögren and Sundin 1996). Leaf temperature was set at 25 °C, and the relative humidity in the leaf cuvette ranged between 46 and 50 %. The chlorophyll fluorescence yield (i.e. the quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII) in the light, ) was measured using a saturating pulse of white light (10 000 μmol m−2 s−1) (Genty et al. 1989). Mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion was calculated using the variable J method (Harley et al. 1992). As this work was conducted in the field, it was not possible to calibrate electron transport rate under non-photorespiratory conditions; therefore, a standard calibration where α = 0.85 and β = 0.5 was used in the calculation of Gm (Gilbert et al. 2012; Walker and Cousins 2013). The variable J method is sensitive to the estimation of the CO2 compensation point to photorespiration (Γ*) and leaf respiration (Gilbert et al. 2012). While measurements of dark respiration (Rn) were also made at ambient CO2 concentration in the dark on the same leaves, Γ* used in the gas exchange algorithm was calculated from the Rubisco-specific factors of Galmes et al. (2005) using the photosynthetic constants of Von Caemmerer (2000) and formulae of Brooks and Farquhar (1985) (Q. spinosa: Γ* = 52.513 μmol−1 mol; S. atopantha: Γ* = 54.145 μmol−1 mol and R. dentatus: Γ* = 52.512 μmol−1 mol). As Γ* is a relatively conservative parameter (Harley et al. 1992), we assumed that the Γ* value used in the gas exchange algorithm did not affect the estimation of Gm. To reduce diffusion leaks through the chamber gasket (Flexas et al. 2007), a supplementary external chamber gasket composed of the same polymer foam was added to create an interspace between the two gaskets (i.e. a double-gasket design with a 5-mm space separating the internal and external gaskets). Then the CO2 and H2O gradients between the in-chamber air and pre-chamber air were minimized by feeding the infra-red gas analyse exhaust air into the interspace between the chamber and the pre-chamber gaskets (Rodeghiero et al. 2007). Total conductance to CO2 (Gtot) was calculated from mesophyll and stomatal conductance to CO2 following Loreto et al. (1994) as:

| (1) |

Light saturated A/Pi response curves were measured at a leaf temperature of 25 °C and a relative humidity in the leaf cuvette of ∼50 % over a range of [CO2] values on a minimum of five plants per species at each elevation. To remove the effect of stomatal limitation on A, the leaves were first pre-conditioned at a [CO2] of 50 µmol mol−1 for ∼60 min to force stomatal opening as described by Centritto et al. (2003). The concentration of [CO2] within the cuvette was then progressively increased to 2000 µmol mol−1. The photosynthetic parameters Amax (net CO2 assimilation rate under conditions of PPFD and CO2 saturation), Vcmax (RuBP-saturated rate of Rubisco: estimate of the carboxylation efficiency of Rubisco determined from the slope of the A/Pi curve at a [CO2] of 40–200 µmol mol−1) and Jmax (maximum rate of electron transport) were estimated by fitting the mechanistic model of Farquhar et al. (1980).

Leaf sampling, carbon isotope discrimination and leaf nitrogen analysis

Immediately after the gas exchange measurements, two leaves per plant from six plants per species at each elevation were detached and stored in sealed plastic bags for the measurement of leaf area, leaf weight, leaf nitrogen concentration and foliar δ13C. Leaf area was measured with a Li-3000 leaf area metre (LI-COR, Inc.). The leaves were then dried at 80 °C for 48 h, the dry mass recorded and then ground into a fine powder using a ceramic grinding container. Specific leaf area (cm2 g−1) was determined as the leaf area to leaf dry mass ratio. Nitrogen concentration (Nmass, mg g−1) was measured on 0.1 g of dried, ground tissue by using standard Kjeldahl technique and assayed for ammonium with an ultraviolet visible spectrophotometer (Tu1221, Beijing Purkinje General Instrument Company, Beijing, China). Narea (nitrogen concentration on a leaf area basis, g m−2) and PNUE (µmol mol−1 s−1) (Hikosaka et al. 2002) were calculated using the following formulae:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where 14 is the atomic mass of nitrogen.

Carbon isotope composition (δ13C) was measured on 0.001 g of ground dried tissue by using a continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometer. Samples were quantitatively combusted in an elemental analyser (Flash-EA 1112, Thermo Electron, Milano, Italy). The CO2 obtained was injected into the helium stream of the mass spectrometer (DELTAplus XP, ThermoFinnigan, Bremen, Germany). The ratio of isotopes (R = 13C/12C) was measured and used to calculate δ13C referred to the Pee Dee Belemnite standard according to Farquhar and Richards (1984) as follows:

| (4) |

Statistical analysis

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences in the data collected from the plants growing at 2500 and 3500 m a.s.l. using the software package SPSS 13.5 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), and graphs were prepared using SigmaPlot 11.0 software (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Ethics statement

The field study did not involve endangered or protected species. No specific permissions or permits were required for the analysis and collection of Q. spinosa, S. atopantha and R. dentatus leaves from the Wolong Reserve (32°25′–32°53′N, 104°20′–104°41′E; Tibetan-Qinghai area, Sichuan Province, China). The leaves were collected from public land with the consent of the responsible government agency (the Chinese Academy of Forestry).

Results

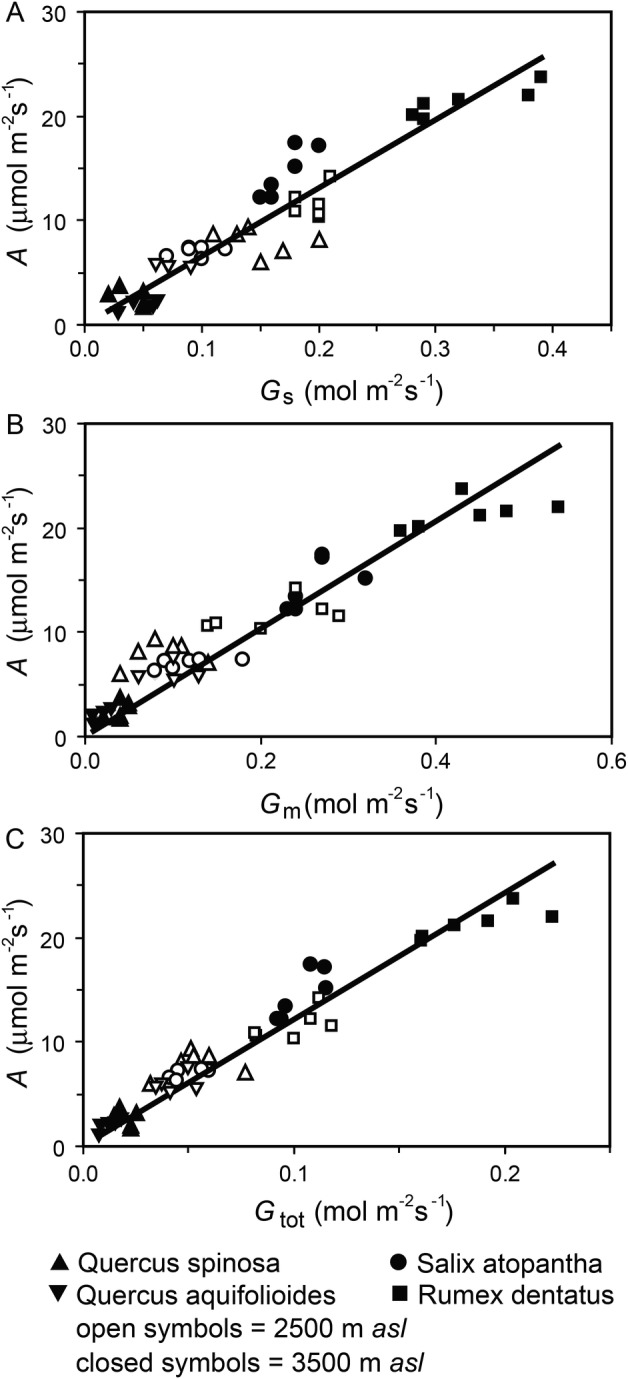

Photosynthesis was closely related to conductance to CO2 in all of the species at high elevations (Fig. 1). Total conductance (Gt) incorporating both Gs and Gm correlated most closely with A (Fig. 1C). However, the species analysed did not display identical responses to increased elevation; Q. spinosa and Q. aquifolioides showed reduced conductance to CO2 with an increase in elevation, while S. atopantha and R. dentatus exhibited higher Gs, Gm and Gtot values at higher elevations (Table 1). The annual herb R. dentatus and deciduous shrub S. atopantha exhibited generally higher values of conductance to CO2 and A than the evergreen Quercus species (Fig. 1). Alterations in Gs and Gm with elevation did not significantly affect Pi/Pa or Pc/Pa ratios in any of the species analysed (Table 1), suggesting modification of the photosynthetic physiology alongside adjustment in conductance to CO2 (Figs 1 and 2). Moreover, the similarity in the ratio of Pi to Pa indicates that any variation in or low values of Ci was unlikely to be responsible for any of the observed patterns in Gm reported in this study (Tholen et al. 2012). Respiration in the dark (Rn) was greater at the higher elevation in all of the species (Table 1). Leaves of Q. spinosa exhibited the lowest Rn values of −1.21 µmol m−2 s−1 at 2500 m a.s.l., but following a 181.8 % increase showed the highest levels of Rn at the greater elevation of 3500 m a.s.l., suggesting that the impact of increased elevation was greatest on the species with sclerophyllous evergreen foliage. The two species with leaf lifespans of <9 months, S. atopantha and R. dentatus, exhibited respective increases of 36.6 and 44.4 % in Rn between 2500 and 3500 m a.s.l.

Figure 1.

Relationship between photosynthesis (A) and stomatal (Gs) (regression R2 = 0.8836, F1,45 = 341.775, P = 1.197 × 10−22), mesophyll (Gm) (regression R2 = 0.916, F1,45 = 502.780, P = 2.107 × 10−26) and total (Gtot) (regression R2 = 0.943, F1,45 = 745.674, P = 1.195 × 10−29) conductance to CO2 at high elevations of 2500 m (open symbols) and 3500 m (filled symbols) a.s.l. of Q. spinosa (upward triangles), S. atopantha (circles) and R. dentatus (squares) from this study and Q. aquifolioides (inverted triangles) from the study of Feng et al. (2013).

Table 1.

Leaf assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance (Gs), mesophyll conductance (Gm), Pi (CO2 intercellular partial pressure)/Pa (CO2 ambient partial pressure), Pc (CO2 chloroplast partial pressure)/Pa and Rd (dark respiration) values of the three plants growing at higher and lower altitudes. Means of a parameter followed by the same letter were not statistically different using a one-way ANOVA (P > 0.05) with least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test.

| Q. spinosa | S. atopantha | R. dentatus | F5,30 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (μmol m−2 s−1) | |||||

| Low elevation | 8.00 ± 0.45 b | 7.02 ± 0.17 b | 11.62 ± 0.54 c | 127.316 | 2.907 × 10−19 |

| High elevation | 2.59 ± 0.30 a | 14.57 ± 0.88 c | 21.33 ± 0.54 d | ||

| Gs (mol m−2 s−1) | |||||

| Low elevation | 0.15 ± 0.01 b | 0.10 ± 0.01 c | 0.19 ± 0.01 d | 79.759 | 2.096 × 10−16 |

| High elevation | 0.04 ± 0.01 a | 0.17 ± 0.01 d | 0.33 ± 0.02 e | ||

| Gm (mol m−2 s−1) | |||||

| Low elevation | 0.09 ± 0.01 a | 0.12 ± 0.01 a | 0.21 ± 0.02 c | 63.573 | 4.712 × 10−15 |

| High elevation | 0.04 ± 0.01 b | 0.26 ± 0.01 c | 0.44 ± 0.02 d | ||

| Rn (μmol m−2 s−1) | |||||

| Low elevation | 1.21 ± 0.04 a | 1.34 ± 0.12 ab | 1.69 ± 0.14 b | 24.353 | 9.959 × 10−10 |

| High elevation | 3.41 ± 0.29 e | 1.83 ± 0.06 c | 2.44 ± 0.12 d | ||

| Pi/Pa | |||||

| Low elevation | 0.56 ± 0.02 a | 0.58 ± 0.01 a | 0.65 ± 0.02 b | 3.549 | 0.0122 |

| High elevation | 0.58 ± 0.02 a | 0.61 ± 0.01 ab | 0.65 ± 0.01 b | ||

| Pc/Pa | |||||

| Low elevation | 0.31 ± 0.02 a | 0.35 ± 0.02 ab | 0.42 ± 0.03 b | 4.444 | 0.00379 |

| High elevation | 0.31 ± 0.03 a | 0.36 ± 0.01 a | 0.44 ± 0.01 b | ||

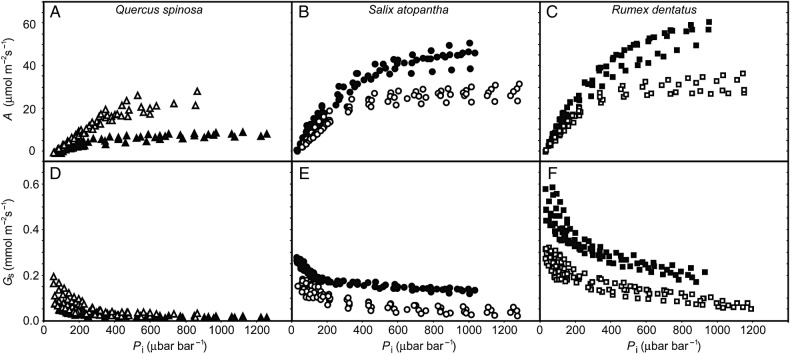

Figure 2.

Photosynthetic response curves to internal [CO2] (A/Pi) and stomatal response to [CO2] of plants growing at high elevations of 2500 m (open symbols) and 3500 m (filled symbols) a.s.l. of Q. spinosa (A and D), S. atopantha (B and E) and R. dentatus (C and F). Symbols as in Fig. 1.

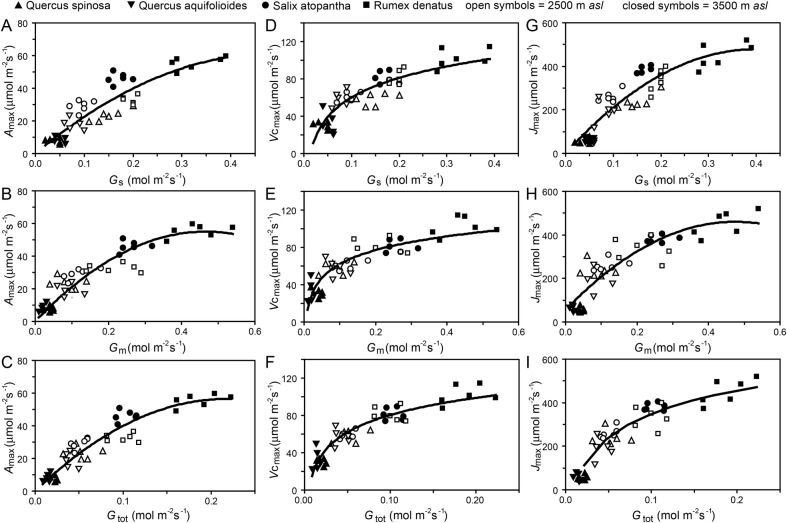

Photosynthetic response curves to increased [CO2] (Fig. 2) performed in situ suggest that modification of the photosynthetic physiology with elevation occurred in concert with shifts in Gtot. Quercus spinosa exhibited 46.5 and 76.1 % reductions in Vcmax and Jmax, respectively, that translated into 56 % reduction in the ratio of Jmax to Vcmax (Table 2). In contrast, both S. atopantha and R. dentatus exhibited increased values of conductance to CO2 (Table 1) and corresponding increases in the physiological capacity to assimilate CO2 (Table 2). Salix atopantha and R.dentatus, respectively, showed 38.1 and 25.4 % increases in Vcmax alongside 52.8 and 34.7 % rises in Jmax that did not significantly alter the Jmax to Vcmax ratio of either species. The maximum rate of photosynthesis (Amax), Vcmax and Jmax all correlated to Gs, Gm and Gtot (Fig. 3). However, at higher Gs, Gm and Gtot values, photosynthetic capacity stabilizes and no longer increases, possibly due to physiological limitations to the rate of photosynthesis. Individuals of the annual herb R. dentatus at the higher elevation displayed the greatest values of Amax, Vcmax and Jmax, while at the higher elevation, Quercus species exhibited the lowest levels of conductance and photosynthetic capacity to assimilate CO2 (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Photosynthetic parameters of the three species growing at lower and higher elevations (detailed in Table 1). Values of Amax, Vcmax and Jmax were obtained by fitting the Farquhar et al. (1980) model of leaf photosynthesis to five A/Pi response curves for each species at each elevation. Means of a parameter followed by the same letter were not statistically different using a one-way ANOVA (P > 0.05) with LSD post hoc test.

| Q. spinosa | S. atopantha | R. dentatus | F5,30 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amax (μmol m−2 s−1) | |||||

| Low elevation | 23.31 ± 1.33 b | 28.52 ± 1.18 c | 32.50 ± 0.95 d | 171.800 | 3.934 × 10−21 |

| High elevation | 7.75 ± 0.55 a | 46.02 ± 1.23 d | 55.45 ± 1.47 e | ||

| Vcmax (μmol m−2 s−1) | |||||

| Low elevation | 58.26 ± 2.42 b | 58.56 ± 2.22 b | 81.25 ± 2.87 c | 72.301 | 8.123 × 10−6 |

| High elevation | 31.73 ± 1.66 a | 80.85 ± 2.49 c | 101.90 ± 3.86 c | ||

| Jmax (μmol m−2 s−1) | |||||

| Low elevation | 236.70 ± 13.06 b | 249.49 ± 13.40 b | 334.37 ± 19.66 c | 79.564 | 2.168 × 10−16 |

| High elevation | 56.65 ± 4.36 a | 381.31 ± 6.49 c | 450.36 ± 21.61 d | ||

| Jmax/Vcmax | |||||

| Low elevation | 4.09 ± 0.24 b | 4.25 ± 0.10 b | 4.10 ± 0.15 b | 41.107 | 1.533 × 10−12 |

| High elevation | 1.80 ± 0.13 a | 4.73 ± 0.09 b | 4.42 ± 0.16 b | ||

Figure 3.

Relationship between photosynthetic physiological capacity to assimilate CO2 (Amax, Vcmax and Jmax) and conductance to CO2 (Gs, Gm and Gtot) at high elevations of 2500 m (open symbols) and 3500 m (filled symbols) a.s.l. of Q. spinosa (upward triangles), S. atopantha (circles) and R. dentatus (squares) from this study and Q. aquifolioides (inverted triangles) from the study of Feng et al. (2013). (A) Amax versus Gs (regression R2 = 0.791, F1,45 = 147.009, P = 1.272 × 10−15); (B) Amax versus Gm (regression R2 = 0.847, F1,45 = 227.498, P = 3.250 × 10−19); (C) Amax versus Gtot (regression R2 = 0.872, F1,45 = 223.520, P = 7.399 × 10−19); (D) Vcmax versus Gs (regression R2 = 0.788, F1,45 = 156.650, P = 4.277 × 10−16); (E) Vcmax versus Gm (regression R2 = 0.794, F1,45 = 141.911, P = 1.642 × 10−15); (F) Vcmax versus Gtot (regression R2 = 0.859, F1,45 = 181.645, P = 3.186 × 10−17); (G) Jmax versus Gs (regression R2 = 0.834, F1,45 = 149.711, P = 9.323 × 10−16); (H) Jmax versus Gm (regression R2 = 0.818, F1,45 = 136.184, P = 3.323 × 10−15); (I) Jmax versus Gtot (regression R2 = 0.883, F1,45 = 161.692, P = 2.470 × 10−16).

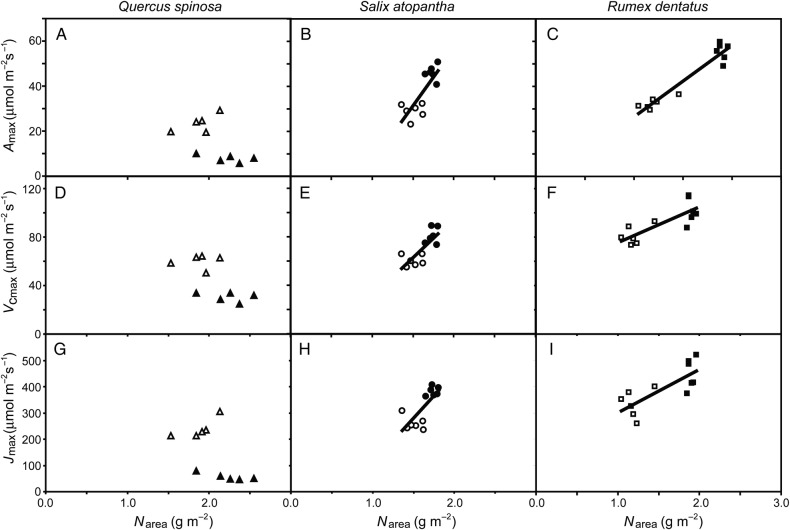

The photosynthetic capacity of a leaf is generally related to the concentration of nitrogen within the foliage (Evans 1989). Both S. atopantha and R. dentatus showed increases in leaf nitrogen alongside Amax, Vcmax and Jmax with elevation (Fig. 4). Despite exhibiting reduced photosynthetic capacity and a 57 % increase in nitrogen concentration at higher elevations, Q. spinosa showed no significant relationship between leaf nitrogen and Amax, Vcmax and Jmax. The PNUE values of S. atopantha and R. dentatus increased by 79.4 and 16.7 % at the higher elevation, while Q. spinosa showed a 69.2 % reduction of PNUE at 3500 m a.s.l. All three species showed increased foliar nitrogen concentration at the higher elevation, but this did not correspond to an increase in SLA (Table 3). While the evergreen Q. spinosa and annual herb R. dentatus showed respective reductions of 13.0 and 31.5 % in SLA at higher elevation, the SLA of S. atopantha was relatively unchanged. Growth at the higher elevation of 3500 m resulted in significant increases of 5.3–10.2 % in the foliar δ13C of all three species. The δ13C values of the plants from 2500 m a.s.l. were significantly enriched in the heavier 13C isotope relative to C3 plants growing at sea level (approximately +1–2‰) (Körner et al. 1988), and this enrichment in 13C became more pronounced at 3500 m a.s.l. (approximately +3–4‰).

Figure 4.

Relationship between foliar nitrogen concentration (Narea) and parameters of physiological photosynthetic capacity (Amax, Vcmax and Jmax) of Q. spinosa (upward triangles), S. atopantha (circles) and R. dentatus (squares) grown at high elevations of 2500 m (open symbols) and 3500 m (filled symbols) a.s.l. Quercus spinosa: (A) Amax versus Narea (regression R2 = 0.285, F1,45 = 3.195, P = 0.112); (D) Vcmax versus Narea (regression R2 = 0.394, F1,45 = 5.197, P = 0.0521) and (G) Jmax versus Narea (regression R2 = 0.310, F1,45 = 3.589, P = 0.0948). Salix atopantha: (B) Amax versus Narea (regression R2 = 0.633, F1,45 = 17.216, P = 0.00198); (E) Vcmax versus Narea (regression R2 = 0.604, F1,45 = 15.260, P = 0.00293) and (H) Jmax versus Narea (regression R2 = 0.550, F1,45 = 12.236, P = 0.00575). Rumex dentatus: (C) Amax versus Narea (regression R2 = 0.919, F1,45 = 113.380, P = 8.914 × 10−07); (F) Vcmax versus Narea (regression R2 = 0.639, F1,45 = 17.7124, P = 0.00180) and (I) Jmax versus Narea (regression R2 = 0.596, F1,45 = 14.733, P = 0.00327).

Table 3.

Leaf carbon isotopic composition (δ13C), SLA, leaf nitrogen concentration per unit mass (Nmass), leaf nitrogen concentration per unit area (Narea) and leaf PNUE of the three plants growing at lower and higher elevations (elevations detailed in Table 1). Means of a parameter followed by the same letter were not statistically different using a one-way ANOVA (P > 0.05) with LSD post hoc test.

| Q. spinosa | S. atopantha | R. dentatus | F5,30 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ13C (‰) | |||||

| Low elevation | −28.04 ± 0.03 c | −29.28 ± 0.19 b | −30.63 ± 0.09 a | 35.525 | 9.894 × 10−12 |

| High elevation | −26.23 ± 0.34 d | −27.74 ± 0.06 c | −27.52 ± 0.18 c | ||

| SLA (cm2 g−1) | |||||

| Low elevation | 92.82 ± 2.01 b | 145.95 ± 5.68 c | 288.31 ± 11.34 d | 29.869 | 2.109 × 10−10 |

| High elevation | 80.71 ± 3.22 a | 145.68 ± 2.68 c | 197.59 ± 2.24 e | ||

| Narea (g m−2) | |||||

| Low elevation | 1.87 ± 0.09 c | 1.51 ± 0.04 b | 1.21 ± 0.05 a | 147.774 | 3.182 × 10−19 |

| High elevation | 2.23 ± 0.11 d | 1.74 ± 0.02 c | 1.90 ± 0.02 cd | ||

| PNUE (μmol mol−1 s−1) | |||||

| Low elevation | 63.65 ± 4.64 b | 65.56 ± 2.44 b | 134.82 ± 1.71 d | 210.276 | 2.101 × 10−22 |

| High elevation | 19.61 ± 1.65 a | 117.64 ± 8.36 c | 157.38 ± 4.25 d | ||

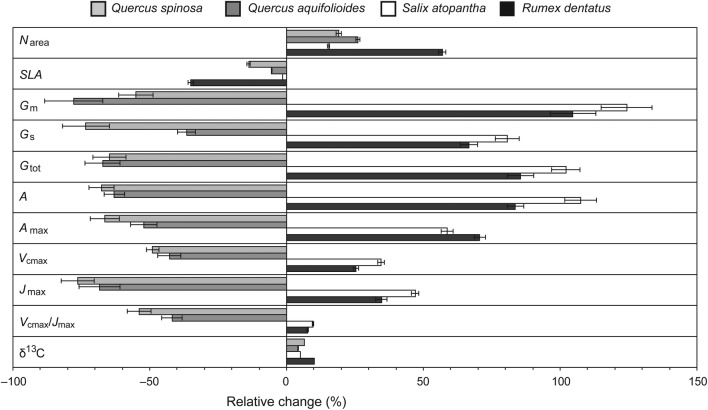

The results of this study have indicated the coordination of photosynthetic, gas exchange and morphological foliar responses to growth at high elevations of 2500 and 3500 m a.s.l. Nonetheless, two generally divergent responses to increased elevation become apparent from the study between the evergreen Quercus species with leaf lifespans of 1–3 years, and S. atopantha and R. dentatus that possess foliage with a leaf lifespan of <9 months. To illustrate these contrasting leaf responses to increased elevation, the relative changes of the physiological, morphological and compositional responses were plotted in Fig. 5. These suggest that the sclerophyllous Quercus species generally reduce conductance to CO2 and photosynthetic capacity with an increase in elevation from 2500 to 3500 m a.s.l., while the shorter-lived foliage of S. atopantha and R. dentatus showed the opposite response.

Figure 5.

Relative effect of an increase in elevation from 2500 to 3500 m a.s.l. on photosynthetic, morphological and compositional characteristics of Q. spinosa, S. atopantha and R. dentatus from this study and Q. aquifolioides from the study of Feng et al. (2013). Error bars indicate 1 SE.

Discussion

The results of our study have demonstrated contrasting physiological and morphological plasticity responses to an increase in elevation from 2500 to 3500 m a.s.l. in three Chinese montane species. Quercus spinosa and Q. aquifolioides possess robust sclerophyllous evergreen foliage with an average leaf lifespan >1 year. These Quercus species generally showed reductions in leaf gas exchange and photosynthetic capacity at the higher elevation. In contrast, the shorter-lived mesophytic foliage of S. atopantha and R. dentatus exhibited increases in conductance to CO2 and the capacity of photosynthetic physiology at the higher elevation (Fig. 5). This may suggest that the response of the plant species analysed to increased elevation was associated with growth habit and leaf economic traits (Milla and Reich 2011).

A rise in elevation confers a number of challenges to photosynthesis such as reduced pCO2 and temperature (Körner 2007). Despite the contrasting responses in terms of conductance to CO2 and photosynthetic physiology observed among different species in this study, increased elevation did result in more positive foliar δ13C, greater nitrogen concentration, enhanced Rn and reduced SLA in all species. At the same latitude, the δ13C of CO2 within the atmosphere is generally lower at high elevations (Trolier et al. 1996). The increased δ13C observed in all four species growing at 3500 m reflects the lower availability of CO2 reducing discrimination against 13C (Farquhar et al. 1989), despite the heavier isotope forming a reduced proportion of CO2 at the higher elevation (Trolier et al. 1996). The δ13C of a leaf is frequently affected by Gs and is indicative of the water use efficiency of a plant (Farquhar and Richards 1984; Farquhar et al. 1989). However, δ13C increases in all three species, despite S. atopantha and R. dentatus exhibiting increased Gs at the higher elevation (Fig. 1), suggest that at elevations >2500 m, factors other than Gs may influence carbon isotope discrimination. The increase in δ13C values of plants with elevation is commonly considered to reflect reduced Pi/Pa ratios. However, due to modification of Gtot, Vcmax and Jmax with elevation, none of the species analysed in this study exhibited reduced Pi/Pa ratios at the higher elevation (Table 1). Nonetheless, increased foliar δ13C observed in this study may indicate longer-term reductions in the Pi/Pa ratio of the three species that was not apparent during the comparatively short duration of the gas exchange measurements. However, the δ13C values of the species analysed in this study are at the lower end of the range of values exhibited by plant species adapted to growth at high elevations (i.e. >2500 m) (Körner et al. 1988), possibly indicating that the combination of reduced Pi/Pa ratios alongside the decreased availability of CO2 may induce lower δ13C values in other species.

The concentration of nitrogen per unit leaf area of the four species increased on average 29.4 % with a rise in elevation from 2500 to 3500 m a.s.l. (Fig. 5). Foliar nitrogen content and SLA are positively related to A (Poorter et al. 1990; Terashima et al. 2011). Point gas exchange measurements of A were taken under identical conditions of temperature, light and [CO2] at both 2500 and 3500 m a.s.l. This showed increased A at the higher elevation in the two species with short-lived foliage and lower A in the evergreen Quercus leaves. The greater values of A at the higher elevation in the two species where Gs and Gm rose with elevation may suggest that temperature plays a major role in limiting photosynthesis, thus affecting δ13C and determining the response of plants to elevation. In plants adapted to cool climates, leaves developed under low temperatures exhibited higher Vcmax and Jmax values (Bunce 2000). However, despite exhibiting an increase in Narea at the higher elevation, the two Quercus species showed reductions in A, Vcmax and Jmax at the greater elevation; this suggests that the greater Narea observed in Q. spinosa and Q. aquifolioides at the higher elevation was not associated with increased allocation of nitrogen to photosynthetic physiology (cf. Shi et al. 2006), or that diffusive limitations imposed by reduced Gs and Gm constrain any effect of increased allocation of nitrogen to RubisCO on A (e.g. Centritto et al. 2003; Loreto and Centritto 2008). The decrease in the Jmax to Vcmax ratio observed in Q. spinosa is indicative of reduced allocation of nitrogen into light harvesting activities (Wullschleger 1993), possibly due to increased levels of radiation at the higher elevation. The greater values of A evident at higher elevations from the point measurements of leaf gas exchange at identical light and temperature may reflect the enhanced photosynthetic capacity and Gtot of S. atopantha and R. dentatus. This enhancement of A at higher elevations would likely not be evident under ambient growth conditions where temperatures and high incident radiation would not be conducive to photosynthesis (Fujimura et al. 2010). Woody species with thick sclerophyllous leaves generally have lower levels of Gtot than deciduous species that exhibit higher SLA values (Centritto et al. 2011). This lower conductance to CO2 reduces Pc levels and as a result constrains photosynthetic rates (Flexas et al. 2013; Lauteri et al. 2014). Any increase in the availability of CO2 will disproportionately affect evergreen species with low SLA values due to this limitation on transport of CO2 to the chloroplast envelope (Centritto et al. 2011; Niinemets et al. 2011). Future rises in atmospheric [CO2] would, therefore, most likely favour evergreen species growing at high elevations such as Q. spinosa rather than those plants with short leaf lifespans such as S. atopantha that exhibit increased Gtot with elevation (Table 1).

The divergent responses between the species may be due to the selective pressures associated with long- and short-lived foliage (Reich et al. 1991). Higher elevations experience factors such as increased incident radiation, drier air and stronger winds that increase the leaf to air vapour pressure deficit and the transpirative demand per unit leaf area (Körner and Diemer 1987; Körner 2007; Kouwenberg et al. 2007). Evergreen species such as Q. spinosa and Q. aquifolioides maintain leaves during periods that are not conducive to photosynthesis; this may necessitate a reduction in levels of Gs to prevent desiccation. In contrast, at higher elevations, the species with short-lived foliage can more fully exploit episodes where conditions are favourable to photosynthesis through enhanced levels of Gs and Gm at higher elevations before dispensing with leaves when growth conditions deteriorate and excessive transpirative and carbon balance costs are incurred. This behaviour does, however, incur costs in terms of the replacement of foliage each year, accounting for the lower SLA values of S. atopantha and R. dentatus in comparison with the two species of Quercus (Table 3). However, the construction costs per leaf are lower as investment in robust foliage capable of tolerating physical abrasion in a high energy windy environment (Wilson 1984) or physiological protection from high levels of harmful radiation over long periods of time is not required for leaves with a short leaf lifespan (Venema et al. 2000).

The number of mitochondria per unit leaf area increases with elevation (Miroslavov and Kravkina 1991), accounting for the increased Rn values at higher elevations observed in this (Table 2) and other studies (Ledig and Korbobo 1983; Shi et al. 2006; Feng et al. 2013). This increased Rn may be associated with lower partial pressures reducing the availability of oxygen (Crawford 1992), the increased respiratory demand required to support an enhanced photosynthetic physiology (Shi et al. 2006) or reduced ambient growth temperatures that result in higher Rn values when Rn is determined at the same leaf temperature (Atkin and Tjoelker 2003). When grown in a common garden study, 11 plant species collected from high elevations exhibited enhanced respiration at high temperatures relative to individuals of the same species that originated at low elevations. However, when temperature was reduced, Rn values were identical between individuals from low and high elevations (Larigauderie and Körner 1995). This may suggest that respiratory adaptation to growth at high elevations is due to the lower temperatures experienced at elevation. Temperature is likely a major factor in shaping plant photosynthetic responses to growth at high elevations. The reduction in temperature associated with an increase in elevation from 2500 to 3500 m a.s.l. will result in lower photosynthetic activity (Brooks and Farquhar 1985). The two species with short leaf lifespans will be able to shed their foliage during winter, whereas the foliage of the evergreen Quercus species will have to withstand the months with the lowest temperatures. This will necessitate a degree of morphological (Cordell et al. 1998) and physiological (Körner and Diemer 1987) tolerance to low temperatures in the evergreen species (Öquist and Huner 2003) and may account for the generally higher values of Rn observed in the leaves of Q. spinosa at 3500 m a.s.l. Furthermore, the effect of the decline in temperature associated with increased elevation is more apparent in trees that are directly affected by atmospheric circulation than shrub or herb layer plants that are smaller and generally sheltered, and as a result under radiation can maintain a significantly higher temperature than the surrounding trees (Körner 2007). This differential effect of temperature changes at high elevation may contribute to the increase in Gtot and photosynthetic capacity observed in S. atopantha and R. dentatus.

Conclusions

The three plant species analysed in this study exhibited significant physiological and morphological plasticity to enable growth at 2500 and 3500 m a.s.l., an elevational gradient equivalent to a 5.5 °C decline in temperature and 11.2 % reduction in pCO2. The results of this study suggest that the physiological and morphological adaptations required for growth at high elevations may be associated with plant growth habit and leaf economics. Consistent with previous studies, all three species showed increased δ13C, Rn and leaf nitrogen at the higher elevation. However, critical differences in the photosynthetic and leaf gas exchange response to elevation were observed between the plants. The evergreen, Q. spinosa, showed reduced conductance to CO2 and diminished levels of Vcmax and Jmax at the higher elevation. In contrast, S. atopantha and R. dentatus with a leaf lifespan of <9 months exhibited increased Gtot and enhanced photosynthetic capacity to fix CO2 at 3500 m. The selective pressures exerted by an increase in elevation may act differently dependent on the leaf lifespan of a species. Those species with short leaf lifespans can more fully exploit favourable growth conditions through increased conductance to CO2 and A before shedding foliage as conditions become less conducive to photosynthesis. Whereas evergreen species need to invest in physically robust leaves and physiological protective mechanisms to endure unfavourable conditions, this may necessitate a decrease in Gs to reduce water loss associated with the higher transpirative demands at higher elevations due to increased wind and radiation. Climate change may affect the plant species that compose high-elevation ecosystems differently depending on leaf economic traits as increased pCO2 is likely to benefit evergreen species with thick sclerophyllous leaves to a greater extent than deciduous species.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 30771718), Project in the National Science and Technology Pillar Program during the Twelfth Five-year Plan Period (No. 2012BAD22B0102); the Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca of Italy: PRIN 2010–2011 ‘PRO-ROOT’ and Progetto Premiale 2012 ‘Aqua’ and a Marie Curie IEF (2010-275626).

Contributions by the Authors

Z.S. and M.C. designed the experiment. Z.S., Q.F. and R.C. conducted the measurements. M.H. and M.C. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

Literature Cited

- Allen DJ, Ort DR. 2001. Impacts of chilling temperatures on photosynthesis in warm-climate plants. Trends in Plant Science 6:36–42. 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01808-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin OK, Tjoelker MG. 2003. Thermal acclimation and the dynamic response of plant respiration to temperature. Trends in Plant Science 8:343–351. 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00136-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y-J, Chen L-Q, Ranhotra PS, Wang Q, Wang Y-F, Li C-S. 2015. Reconstructing atmospheric CO2 during the Plio–Pleistocene transition by fossil Typha. Global Change Biology 21:874–881. 10.1111/gcb.12670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry RG. 2013. Mountain weather and climate. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks A, Farquhar GD. 1985. Effect of temperature on the CO2/O2 specificity of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase and the rate of respiration in the light. Planta 165:397–406. 10.1007/BF00392238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunce JA. 2000. Acclimation of photosynthesis to temperature in eight cool and warm climate herbaceous C3 species: temperature dependence of parameters of a biochemical photosynthesis model. Photosynthesis Research 63:59–67. 10.1023/A:1006325724086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centritto M, Loreto F, Chartzoulakis K. 2003. The use of low [CO2] to estimate diffusional and non-diffusional limitations of photosynthetic capacity of salt-stressed olive saplings. Plant, Cell and Environment 26:585–594. 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.00993.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centritto M, Lauteri M, Monteverdi MC, Serraj R. 2009. Leaf gas exchange, carbon isotope discrimination, and grain yield in contrasting rice genotypes subjected to water deficits during the reproductive stage. Journal of Experimental Botany 60:2325–2339. 10.1093/jxb/erp123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centritto M, Tognetti R, Leitgeb E, Střelcová K, Cohen S. 2011. Above ground processes—anticipating climate change influences. In: Bredemeier M, Cohen S, Godbold DL, Lode E, Pichler V, Schleppi P, eds. Forest management and the water cycle: an ecosystem-based approach. London: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Fu F, Skvortsov AK. 1998. Validation of Hao's new Chinese taxa in Salix (Salicaceae). Novon 8:467–470. 10.2307/3391877 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cordell S, Goldstein G, Mueller-Dombois D, Webb D, Vitousek PM. 1998. Physiological and morphological variation in Metrosideros polymorpha, a dominant Hawaiian tree species, along an altitudinal gradient: the role of phenotypic plasticity. Oecologia 113:188–196. 10.1007/s004420050367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford R. 1992. Oxygen availability as an ecological limit to plant distribution. Advances in Ecological Research 23:93–185. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR. 1989. Photosynthesis and nitrogen relationships in leaves of C3 plants. Oecologia 78:9–19. 10.1007/BF00377192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Richards RA. 1984. Isotopic composition of plant carbon correlates with water-use efficiency of wheat genotypes. Functional Plant Biology 11:539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Caemmerer S, Berry JA. 1980. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149:78–90. 10.1007/BF00386231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT. 1989. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology 40:503–537. 10.1146/annurev.pp.40.060189.002443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Q, Centritto M, Cheng R, Liu S, Shi Z. 2013. Leaf functional trait responses of Quercus aquifolioides to high elevations. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology 15:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Diaz-Espejo A, Galmés J, Kaldenhoff R, Medrano H, Ribas-Carbo M. 2007. Rapid variations of mesophyll conductance in response to changes in CO2 concentration around leaves. Plant, Cell and Environment 30:1284–1298. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01700.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J, Niinemets Ü, Gallé A, Barbour MM, Centritto M, Diaz-Espejo A, Douthe C, Galmés J, Ribas-Carbo M, Rodriguez PL, Rosselló F, Soolanayakanahally R, Tomas M, Wright IJ, Farquhar GD, Medrano H. 2013. Diffusional conductances to CO2 as a target for increasing photosynthesis and photosynthetic water-use efficiency. Photosynthesis Research 117:45–59. 10.1007/s11120-013-9844-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friend AD, Woodward FI, Switsur VR. 1989. Field measurements of photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, leaf nitrogen and δ13C along altitudinal gradients in Scotland. Functional Ecology 3:117–122. 10.2307/2389682 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Friend DJC, Pomeroy ME. 1970. Changes in cell size and number associated with the effects of light intensity and temperature on the leaf morphology of wheat. Canadian Journal of Botany 48:85–90. 10.1139/b70-011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer MJ, Andrews JR, Oxborough K, Blowers DA, Baker NR. 1998. Relationship between CO2 assimilation, photosynthetic electron transport, and active O2 metabolism in leaves of maize in the field during periods of low temperature. Plant Physiology 116:571–580. 10.1104/pp.116.2.571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura S, Shi P, Iwama K, Zhang X, Gopal J, Jitsuyama Y. 2010. Effect of altitude on the response of net photosynthetic rate to carbon dioxide increase by spring wheat. Plant Production Science 13:141–149. 10.1626/pps.13.141 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gale J. 1972a. Availability of carbon dioxide for photosynthesis at high altitudes: theoretical considerations. Ecology 53:494–497. 10.2307/1934239 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gale J. 1972b. Elevation and transpiration: some theoretical considerations with special reference to Mediterranean-type climate. Journal of Applied Ecology 9:691–702. 10.2307/2401898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gale J. 1973. Experimental evidence for the effect of barometric pressure on photosynthesis and transpiration. In: Slatyer RO, ed. Ecology and conservation: plant response to climatic factors. Proceedings of the Uppsala Symposium. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Galmes J, Flexas J, Keys AJ, Cifre J, Mitchell RAC, Madgwick PJ, Haslam RP, Medrano H, Parry MAJ. 2005. Rubisco specificity factor tends to be larger in plant species from drier habitats and in species with persistent leaves. Plant, Cell and Environment 28:571–579. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01300.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Genty B, Briantais J-M, Baker NR. 1989. The relationship between the quantum yield of photosynthetic electron transport and quenching of chlorophyll fluorescence. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 990:87–92. 10.1016/S0304-4165(89)80016-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert ME, Pou A, Zwieniecki MA, Holbrook NM. 2012. On measuring the response of mesophyll conductance to carbon dioxide with the variable J method. Journal of Experimental Botany 63:413–425. 10.1093/jxb/err288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley PC, Loreto F, Di Marco G, Sharkey TD. 1992. Theoretical considerations when estimating the mesophyll conductance to CO2 flux by analysis of the response of photosynthesis to CO2. Plant Physiology 98:1429–1436. 10.1104/pp.98.4.1429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth M, Raschi A. 2014. An assessment of the use of epidermal micro-morphological features to estimate leaf economics of Late Triassic-Early Jurassic fossil Ginkgoales. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 205:1–8. 10.1016/j.revpalbo.2014.02.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth M, Elliott-Kingston C, Mcelwain JC. 2011. Stomatal control as a driver of plant evolution. Journal of Experimental Botany 62:2419–2423. 10.1093/jxb/err086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth M, Killi D, Materassi A, Raschi A. 2015. Coordination of stomatal physiological behavior and morphology with carbon dioxide determines stomatal control. American Journal of Botany 102:677–688. 10.3732/ajb.1400508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka K, Nagamatsu D, Ishii HS, Hirose T. 2002. Photosynthesis-nitrogen relationships in species at different altitudes on Mount Kinabalu, Malaysia. Ecological Research 17:305–313. 10.1046/j.1440-1703.2002.00490.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hovenden MJ, Vander Schoor JK. 2004. Nature vs nurture in the leaf morphology of Southern beech, Nothofagus cunninghamii (Nothofagaceae). New Phytologist 161:585–594. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00931.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J-J, Xing Y-W, Turkington R, Jacques FMB, Su T, Huang Y-J, Zhou Z-K. 2015. A new positive relationship between pCO2 and stomatal frequency in Quercus guyavifolia (Fagaceae): a potential proxy for palaeo-CO2 levels. Annals of Botany 115:777–788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Wang Z, Huang B. 2010. Diffusion limitations and metabolic factors associated with inhibition and recovery of photosynthesis from drought stress in a C3 perennial grass species. Physiologia Plantarum 139:93–106. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2010.01350.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogami H, Hanba YT, Kibe T, Terashima I, Masuzawa T. 2001. CO2 transfer conductance, leaf structure and carbon isotope composition of Polygonum cuspidatum leaves from low and high altitudes. Plant, Cell and Environment 24:529–538. 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00696.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Körner C. 2007. The use of ‘altitude’ in ecological research. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 22:569–574. 10.1016/j.tree.2007.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körner C, Cochrane PM. 1985. Stomatal responses and water relations of Eucalyptus pauciflora in summer along an elevational gradient. Oecologia 66:443–455. 10.1007/BF00378313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körner C, Diemer M. 1987. In situ photosynthetic responses to light, temperature and carbon dioxide in herbaceous plants from low and high altitude. Functional Ecology 1:179–194. 10.2307/2389420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Körner C, Scheel JA, Bauer H. 1979. Maximum leaf diffusive conductance in vascular plants. Photosynthetica 13:45–82. [Google Scholar]

- Körner C, Bannister P, Mark AF. 1986. Altitudinal variation in stomatal conductance, nitrogen content and leaf anatomy in different plant life forms in New Zealand. Oecologia 69:577–588. 10.1007/BF00410366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körner C, Farquhar GD, Roksandic Z. 1988. A global survey of carbon isotope discrimination in plants from high altitude. Oecologia 74:623–632. 10.1007/BF00380063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouwenberg LLR, Kürschner WM, Mcelwain JC. 2007. Stomatal frequency change over altitudinal gradients: prospects for paleoaltimetry. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 66:215–241. 10.2138/rmg.2007.66.9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N, Kumar S, Ahuja PS. 2005. Photosynthetic characteristics of Hordeum, Triticum, Rumex, and Trifolium species at contrasting altitudes. Photosynthetica 43:195–201. 10.1007/s11099-005-0033-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larigauderie A, Körner C. 1995. Acclimation of leaf dark respiration to temperature in alpine and lowland plant species. Annals of Botany 76:245–252. 10.1006/anbo.1995.1093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lauteri M, Haworth M, Serraj R, Monteverdi MC, Centritto M. 2014. Photosynthetic diffusional constraints affect yield in drought stressed rice cultivars during flowering. PLoS ONE 9:e109054 10.1371/journal.pone.0109054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledig FT, Korbobo DR. 1983. Adaptation of sugar maple populations along altitudinal gradients: photosynthesis, respiration, and specific leaf weight. American Journal of Botany 70:256–265. 10.2307/2443271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Zhang X, Liu X, Luukkanen A, Berninger F. 2006. Leaf morphological and physiological responses of Quercus aquifolioides along an altitudinal gradient. Silva Fennica 40:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Yang D, Xiang S, Li G. 2013. Different responses in leaf pigments and leaf mass per area to altitude between evergreen and deciduous woody species. Australian Journal of Botany 61:424–435. 10.1071/BT13022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F, Centritto M. 2008. Leaf carbon assimilation in a water-limited world. Plant Biosystems 142:154–161. 10.1080/11263500701872937 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F, Di Marco G, Tricoli D, Sharkey TD. 1994. Measurements of mesophyll conductance, photosynthetic electron transport and alternative electron sinks of field grown wheat leaves. Photosynthesis Research 41:397–403. 10.1007/BF02183042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F, Tsonev T, Centritto M. 2009. The impact of blue light on leaf mesophyll conductance. Journal of Experimental Botany 60:2283–2290. 10.1093/jxb/erp112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milla R, Reich PB. 2011. Multi-trait interactions, not phylogeny, fine-tune leaf size reduction with increasing altitude. Annals of Botany 107:455–465. 10.1093/aob/mcq261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miroslavov EA, Kravkina IM. 1991. Comparative analysis of chloroplasts and mitochondria in leaf chlorenchyma from mountain plants grown at different altitudes. Annals of Botany 68:195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü. 2001. Global-scale climatic controls of leaf dry mass per area, density, and thickness in trees and shrubs. Ecology 82:453–469. 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0453:GSCCOL]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü, Díaz-Espejo A, Flexas J, Galmés J, Warren CR. 2009. Role of mesophyll diffusion conductance in constraining potential photosynthetic productivity in the field. Journal of Experimental Botany 60:2249–2270. 10.1093/jxb/erp036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü, Flexas J, Peñuelas J. 2011. Evergreens favored by higher responsiveness to increased CO2. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 26:136–142. 10.1016/j.tree.2010.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ögren E, Sundin U. 1996. Photosynthetic responses to variable light: a comparison of species from contrasting habitats. Oecologia 106:18–27. 10.1007/BF00334403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öquist G, Huner NPA. 2003. Photosynthesis of overwintering evergreen plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 54:329–355. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.54.072402.115741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S, Liu C, Zhang W, Xu S, Wang N, Li Y, Gao J, Wang Y, Wang G. 2013. The scaling relationships between leaf mass and leaf area of vascular plant species change with altitude. PLoS ONE 8:e76872 10.1371/journal.pone.0076872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, Remkes C, Lambers H. 1990. Carbon and nitrogen economy of 24 wild species differing in relative growth rate. Plant Physiology 94:621–627. 10.1104/pp.94.2.621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H, Niinemets Ü, Poorter L, Wright IJ, Villar R. 2009. Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): a meta-analysis. New Phytologist 182:565–588. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02830.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich PB, Uhl C, Walters MB, Ellsworth DS. 1991. Leaf lifespan as a determinant of leaf structure and function among 23 Amazonian tree species. Oecologia 86:16–24. 10.1007/BF00317383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodeghiero M, Niinemets Ü, Cescatti A. 2007. Major diffusion leaks of clamp-on leaf cuvettes still unaccounted: how erroneous are the estimates of Farquhar et al. model parameters? Plant, Cell and Environment 30:1006–1022. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.001689.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi B, Ming Y. 1987. Wolong vegetation and resource plants. Chengdu, China: Sichuan Science and Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z, Liu S, Liu X, Centritto M. 2006. Altitudinal variation in photosynthetic capacity, diffusional conductance and δ13C of butterfly bush (Buddleja davidii) plants growing at high elevations. Physiologia Plantarum 128:722–731. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2006.00805.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Masuzawa T, Ohba H, Yokoi Y. 1995. Is photosynthesis suppressed at higher elevations due to low CO2 pressure? Ecology 76:2663–2668. 10.2307/2265838 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Hanba YT, Tholen D, Niinemets Ü. 2011. Leaf functional anatomy in relation to photosynthesis. Plant Physiology 155:108–116. 10.1104/pp.110.165472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholen D, Ethier G, Genty B, Pepin S, Zhu X-G. 2012. Variable mesophyll conductance revisited: theoretical background and experimental implications. Plant, Cell and Environment 35:2087–2103. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02538.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trolier M, White JWC, Tans PP, Masarie KA, Gemery PA. 1996. Monitoring the isotopic composition of atmospheric CO2: measurements from the NOAA Global Air Sampling Network. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 101:25897–25916. 10.1029/96JD02363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venema JH, Villerius L, Van Hasselt PR. 2000. Effect of acclimation to suboptimal temperature on chilling-induced photodamage: comparison between a domestic and a high-altitude wild Lycopersicon species. Plant Science 152:153–163. 10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00228-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Von Caemmerer S. 2000. Biochemical models of leaf photosynthesis. Collingwood, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Walker BJ, Cousins AB. 2013. Influence of temperature on measurements of the CO2 compensation point: differences between the Laisk and O2-exchange methods. Journal of Experimental Botany 64:1893–1905. 10.1093/jxb/ert058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Yu G, He N, Wang Q, Xia F, Zhao N, Xu Z, Ge J. 2014. Elevation-related variation in leaf stomatal traits as a function of plant functional type: evidence from Changbai Mountain, China. PLoS ONE 9:e115395 10.1371/journal.pone.0115395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren CR. 2007. Stand aside stomata, another actor deserves centre stage: the forgotten role of the internal conductance to CO2 transfer. In: 14th International Congress of Photosynthesis Oxford University Press, Glasgow, Scotland. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DG, Black RA. 1993. Phenotypic variation in contrasting temperature environments: growth and photosynthesis in Pennisetum setaceum from different altitudes on Hawaii. Functional Ecology 7:623–633. 10.2307/2390140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. 1984. Microscopic features of wind damage to leaves of Acer pseudoplatanus L. Annals of Botany 53:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward FI. 1986. Ecophysiological studies on the shrub Vaccinium myrtillus L. taken from a wide altitudinal range. Oecologia 70:580–586. 10.1007/BF00379908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward FI, Bazzaz FA. 1988. The responses of stomatal density to CO2 partial pressure. Journal of Experimental Botany 39:1771–1781. 10.1093/jxb/39.12.1771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZY, Raven PH, Hong DY. 2011. Flora of China Volume 20-21. St. Louis: Beijing Science Press and Missouri Botanical Garden Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger SD. 1993. Biochemical limitations to carbon assimilation in C3 plants—a retrospective analysis of the A/Ci curves from 109 species. Journal of Experimental Botany 44:907–920. 10.1093/jxb/44.5.907 [DOI] [Google Scholar]