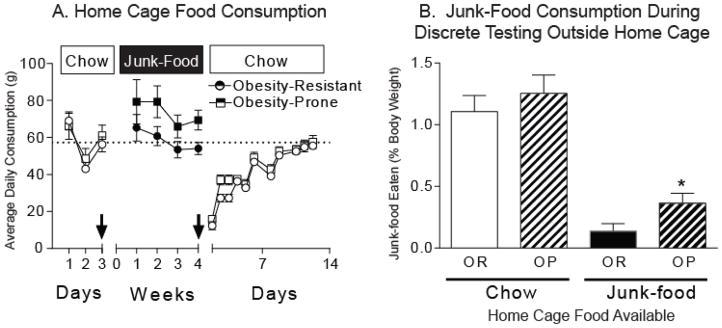

Figure 5. Obesity-prone rats over-consume junk-food, even in the face of over-abundance.

A) Average daily home-cage food consumption (± SEM). Boxes show the type of food available. Arrows indicate discrete junk-food consumption tests conducted outside the home cage (20 min/test). Chow intake was similar between groups, and obesity-prone rats tended to eat more junk-food than obesity-resistant rats. In addition, both obesity-prone and obesity-resistant rats dramatically reduce their home cage food intake when returned to standard lab chow, and took nearly two weeks to resume pre-junk-food diet levels of chow intake. B) Average (± SEM) junk-food consumed relative to total body weight during discrete (20 min) testing outside the home cage. When only standard lab chow was available in the home cage, discrete junk-food consumption was similar between groups (light bars). However, after 4 weeks of free access to junk-food in the home cages, obesity-prone rats still consumed significantly more junk-food puring discrete testing than obesity-resistant rats, even when differences in body weight were taken into account (dark bars, * p < 0.05). Thus, although access to junk-food in the home cage decreased discrete consumption in general, obesity-prone rats over-consumed junk-food, despite having continual free access to the same food in their home cages.