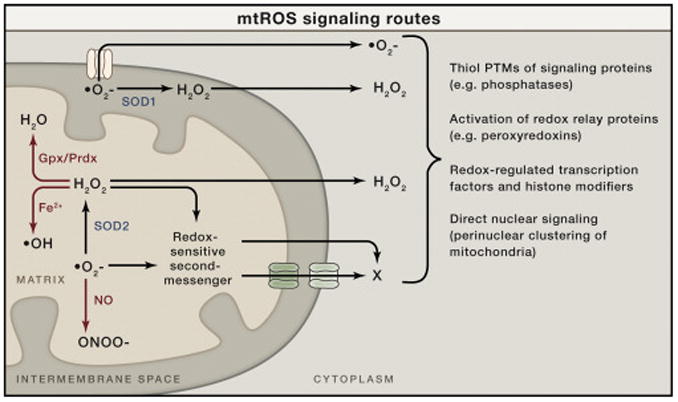

Figure 1. Mitochondrial ROS Signaling Basics.

Superoxide (O2–) is generated on both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane and hence arises in the matrix or the intermembrane space (IMS). Superoxide can be converted to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by superoxide dismutase enzymes (SOD1 in the IMS or SOD2 in the matrix). The resulting hydrogen peroxide can cross membranes and enter the cytoplasm to promote redox signaling. Superoxide is not readily membrane permeable but may be released into the cytoplasm through specific outer membrane channels, as shown (see main text). In addition to signaling in the cytoplasm directly, both superoxide and hydrogen peroxide could, in principle, oxidize or modify other molecules in mitochondria that can be released into the cytoplasm to signal (redox-sensitive second messenger; X). These mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) can generate signaling responses and changes in nuclear gene expression in multiple ways (shown to the right). There are other fates of mtROS that would prevent signaling (or potentially enact other signaling and damage responses). For example, superoxide can react with nitric oxide (NO) to form peroxinitrite (ONOO–). This would prevent its conversion to hydrogen peroxide, could cause damage by the highly reactive peroxynitrite, and could potentially limit NO availability for its own type of signaling. Hydrogen peroxide can be eliminated enzymatically by glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) in the matrix or peroxiredoxins (Prdx) in the matrix and elsewhere in the cell. Peroxyredoxins can also promote redox signaling by promoting disulfide bond formation in target proteins. Finally, in the presence of transition metals, hydrogen peroxide can generate damaging hydroxyl radicals (OH).