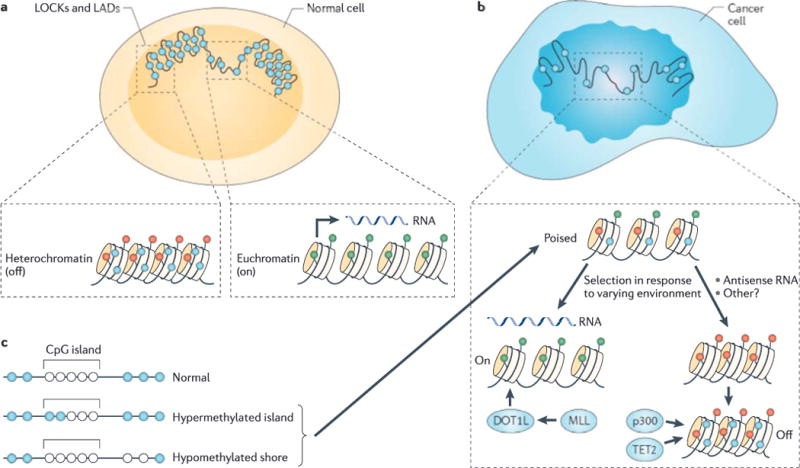

Figure 1. Alterations in the cancer epigenome that can cause epigenetic dysregulation.

a | Large organized chromatin lysine modifications (LOCKs) and lamin-associated domains (LADs) (shown here in large scale) are associated with the nuclear membrane and are generally heterochromatic, with a high level of DNA methylation. Transcriptionally active genes have less compact nucleosomes than silent genes, and active and silent genes are distinguished by differing post-translational modifications of histones (green represents on and red represents off), as well as increased DNA methylation (shown in blue) of silent genes, b | In cancer there is a reduction of LOCKs, as well as general disorganization of the nuclear membrane and hypomethylation of large blocks of DNA corresponding approximately to the LOCKs and LADs. Chromatin is in a more stem cell-like state with the ability to differentiate into euchromatin and hypomethylated genes, or into heterochromatin and hypermethylated genes. Our argument is that epigenetic dysregulation allows for selection in response to the cellular environment for cellular growth advantage at the expense of the host. Mechanisms include mutations in epigenetic regulatory genes (for example, DOT1-like (DOT1L), mixed lineage leukaemia (MLL), EP300 (which encodes p300) and tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2 (TET2)) and primary epigenetic modifications with positive feedback. c | Loss of boundary stability of methylation at CpG islands includes the encroaching of boundaries, leading to CpG island hypermethylation, and the shifting out of boundaries, leading to hypomethylated CpG shores. Both mean shifts in methylation and hypervariability allow for selection.