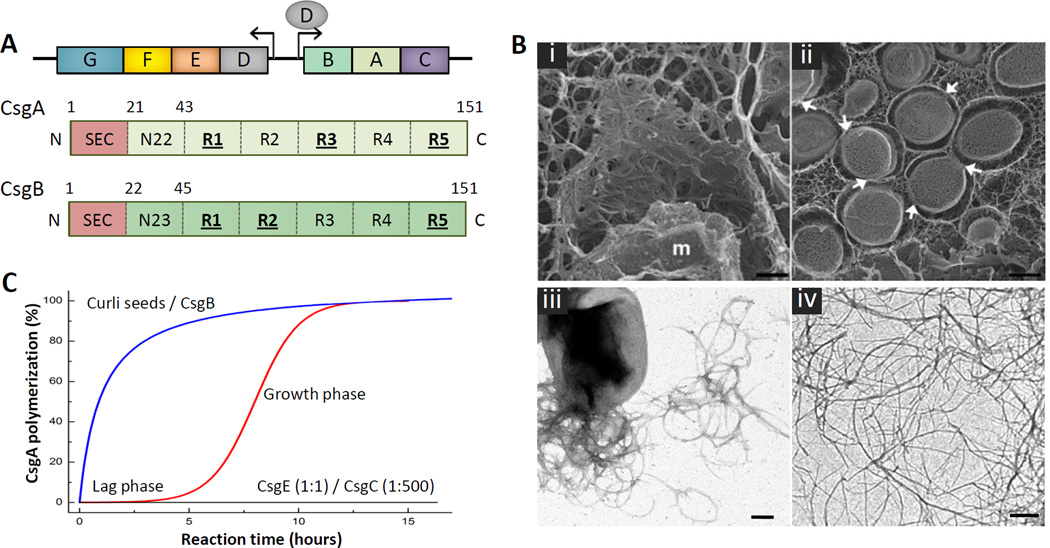

Figure 1. Curli composition and structure.

(A) Organization of the csgBAC and csgDEFG curli operons and architecture of the curli subunits CsgA (light green) and CsgB (dark green). The N-terminal signal sequence (SEC; red) is cleaved after export into the periplasm. The mature subunits contain an N-terminal curli-specific targeting sequence (N22 or N23 in CsgA and CsgB, respectively) that is followed by a pseudo-repeat region (R1 to R5) that forms the amyloidogenic core of the curli subunits (green). Repeats that efficiently self-polymerize in vitro are underscored. (B) Electron microscopy of curli fibers. (i, ii) Freeze-fracture EM of E. coli biofilms shows bacterial cells are encased in a matrix supported by interwoven curli. Bacteria appear to come into contact with the matrix only at discrete locations (white arrows); (m: fractioned bacterial membrane); scale bars 500 nm. (reproduced from [12]). (iii, iv) Transmission EM of individual E. coli cells producing curli fibers (iii), and curli-like fibers grown in vitro from purified CsgA (iv); scale bars: 200 nm. (C) Representation of typical in vitro CsgA polymerization profiles under different conditions. The addition of preformed fibers or the CsgB nucleator removes the lag phase preceding exponential fiber growth (blue curve). In the presence of CsgE (1:1 ratio) or CsgC (1:500 ratio), no CsgA polymerization is observed (black curve) [24].