Abstract

Reward-processing involves two temporal stages characterized by two distinct neural processes: reward-anticipation and reward-outcome. Intriguingly, very little research has examined the relationship between neural processes involved in reward-anticipation and reward-outcome. To investigate this, one needs to consider the heterogeneity of reward-processing within each stage. To identify different stages of reward processing, we adapted a reward time-estimation task. While EEG data were recorded, participants were instructed to button-press 3.5 s after the onset of an Anticipation-Cue and received monetary reward for good time-estimation on the Reward trials, but not on No-Reward trials. We first separated reward-anticipation into event related potentials (ERPs) occurring at three sub-stages: reward/no-reward cue-evaluation, motor-preparation and feedback-anticipation. During reward/no-reward cue-evaluation, the Reward-Anticipation Cue led to a smaller N2 and larger P3. During motor-preparation, we report, for the first time, that the Reward-Anticipation Cue enhanced the Readiness Potential (RP), starting approximately 1 s before movement. At the subsequent feedback-anticipation stage, the Reward-Anticipation Cue elevated the Stimulus-Preceding Negativity (SPN). We also separated reward-outcome ERPs into different components occurring at different time-windows: the Feedback-Related Negativity (FRN), Feedback-P3 (FB-P3) and Late-Positive Potentials (LPP). Lastly, we examined the relationship between reward-anticipation and reward-outcome ERPs. We report that individual-differences in specific reward-anticipation ERPs uniquely predicted specific reward-outcome ERPs. In particular, the reward-anticipation Early-RP (1 to .8 s before movement) predicted early reward-outcome ERPs (FRN and FB-P3), whereas, the reward-anticipation SPN most strongly predicted a later reward-outcome ERP (LPP). Results have important implications for understanding the nature of the relationship between reward-anticipation and reward-outcome neural-processes.

Keywords: reward anticipation, reward outcome, Readiness Potential, Stimulus Preceding Negativity, Late-Positive Potential, Feedback-Related Negativity

1. Introduction

Prior animal-model and human research suggests that reward-processing can be separated into two temporal stages: reward-anticipation and reward-outcome (Berridge & Robinson, 2003; Knutson, Fong, Adams, Varner, & Hommer, 2001; Liu, Hairston, Schrier, & Fan, 2011; Salamone & Correa, 2012). These stages are thought to be different from each other neuro-chemically, neuro-anatomically, and neuro-physiologically. What remains unclear, however, is the extent to which neural-activity during reward-anticipation is related to individual-differences in neural-activity during reward-outcome. A challenge in investigating this question is that there are several distinct psychological processes embedded within both reward-anticipation and reward-outcome. To investigate the relationship between reward-anticipation and reward-outcome neural activity, it is important to determine which specific components of reward processing are related to each other. The strong temporal resolution of event-related potentials (ERP; Luck, 2005) makes it an ideal method for unpacking the distinct psychological processes within reward processing, and for examining the relationship between reward-anticipation and reward-outcome neural activity.

Several ERP studies have investigated different aspects of reward-anticipation (Brunia, Hackley, van Boxtel, Kotani, & Ohgami, 2011; Goldstein et al., 2006; McAdam & Seales, 1969). From this work it is clear that reward-anticipation is not a homogenous construct, but comprised of at least three sub-stages: (i) reward/no-reward cue-evaluation, (ii) motor-preparation and (iii) feedback-anticipation. Similarly, the reward-outcome stage has also been associated with different ERP components along the temporal scale, each of which is sensitive to different types of outcome evaluation (San Martín, 2012). Nonetheless, how reward-cues modulate ERPs within each of these sub-stages is not well-understood. During motor-preparation, for instance, it is unknown at which time-point reward-related stimuli start to modulate neural-activity to prepare for action. More importantly, the majority of studies to date have focused only on one sub-stage of reward-processing. Few, if any, studies have directly examined the relationship between reward-anticipation and reward-outcome ERPs. Accordingly, we first aimed to isolate ERP components corresponding to different aspects of reward-anticipation and reward-outcome within the same task. By doing so, we clarify the role that reward-related stimuli play at different time points during the anticipation and outcome of reward, as indexed by ERPs. Our second and primary aim was to assess whether (and if so how) ERPs during sub-stages of reward-anticipation relate to individual-differences in reward-outcome ERPs. Examining the relationship between reward-anticipation and reward-outcome neural activity has important implications for understanding the temporal dynamics of reward processing in the brain as well as individual differences in reward-related neural activity.

1.1 Reward-Anticipation ERPs

The reward/no-reward cue-evaluation stage occurs when individuals first evaluate whether their actions can lead to reward. Reward-anticipation cues that signal the possibility of receiving reward lead to more a positive P3 ERP component (Cue-P3; Cue-locked P3) (Broyd et al., 2012; Goldstein et al., 2006; Ramsey & Finn, 1997; Santesso et al., 2012). The P3 is a positive, centro-parietal component that appears around 300 to 500 ms post-cue onset. An elevated Cue-P3 to reward-anticipation cues is consistent with the association between the P3 and stimulus-categorization (Johnson & Donchin, 1980). That is, a stimulus categorized as a response “target” usually elicits a more positive P3, and thus, in the case of reward processing, the rewarding features of a cue may act as a criterion for categorization. In addition to the Cue-P3, recent studies have documented the involvement of the N2, an earlier (around 200-400 ms post-cue onset), more anterior (fronto-central sites), negative-going ERP component at the cue-evaluation stage (Potts, 2011; Santesso et al., 2012). Potts (2011), for instance, assigned reward and punishment conditions to stimuli of a response-selection task. He found reward stimuli elicited a less negative N2 than punishment stimuli, which signaled the possibility of losing money if performance failed to meet accuracy standards. Yet, the mechanism underlying the influence of reward-anticipation cues on the N2 is not clear, given that there are two, relatively independent, known roles of the N2: cognitive-control and template mismatch (Folstein & Van Petten, 2008). Interpreting the N2 as reflecting cognitive-control, Potts (2011) construed variation in N2 amplitude as signaling enhanced cognitive-control devoted to avoiding loss on punishment-anticipation cues. Alternatively, reward-anticipation cues may affect the N2 via a template mismatch mechanism (Folstein & Van Petten, 2008). Specifically, participants may have a positive bias to expect the reward-anticipation cue over the punishment-anticipation cue, making a reward-anticipation cue a “template.” Enhanced N2 to the punishment-anticipation cue may in turn reflect a mismatch with this reward expectation template (Donkers, Nieuwenhuis, & van Boxtel, 2005; Gehring, Gratton, Coles, & Donchin, 1992). To help resolve this issue, the current study will compare the N2 to both reward-anticipation and no-reward-anticipation cues (as opposed to punishment-anticipation cues). Results in line with the cognitive-control account would likely involve a more negative N2 to reward-anticipation cues, given that reward-anticipation cues should elicit stronger cognitive-control relative to no-reward-anticipation cues. Alternatively, results in line with the mismatch account would likely involve a more negative N2 to a no-reward-anticipation cue, given that the presence of a no-reward-anticipation cue indicates a mismatch with one's reward expectation template. Importantly, if either the N2 or the Cue-P3 is modulated by the reward-anticipation cue in the present study, we next will examine the relationships between the N2 and/or Cue-P3 during the reward/no-reward cue-evaluation stage with reward-outcome ERPs.

The second sub-stage of reward-anticipation, motor-preparation, involves preparing to initiate an action required to pursue or obtain reward. Neural-activity during motor-preparation can be measured by the Readiness Potential (RP), a negative, pre-movement ERP component at central sites contralateral to the side of movement (Kornhuber & Deecke, 1965). Compared to other anticipatory ERPs, the influence of reward on the RP has not been frequently studied.1 A classic ERP study showed a heightened RP when monetary reward was distributed randomly following a self-paced movement (McAdam & Seales, 1969). A recent study demonstrated that a goal-directed movement (e.g., moving after 3 seconds as opposed to a self-paced movement) elicited a more negative RP (Baker, Piriyapunyaporn, & Cunnington, 2012). However, whether (and if so, how early before the movement) a reward-anticipation cue leads to a more negative RP preceding a goal-directed movement remains unknown. Understanding the timing of when reward starts to modulate the RP is important, given that the RP has two main temporally-distinct subcomponents: the Early-RP (i.e., earlier than 600 ms before movement) and the Late-RP (Bortoletto, Lemonis, & Cunnington, 2011; Kutas & Donchin, 1980; Shibasaki, Barrett, Halliday, & Halliday, 1980). The Early-RP and Late-RP are thought to be different not only in neural-substrates, but also in their functional-processes (for review, see Shibasaki & Hallett, 2006). Neuroanatomically, the Early-RP corresponds to the supplementary motor area (SMA) and pre-SMA, whereas the Late-RP corresponds to the primary motor cortex (M1) and lateral premotor cortex (Cunnington, Windischberger, Deecke, & Moser, 2002; Shibasaki & Hallett, 2006). Functionally, the Early-RP is associated with abstract representation of motor-preparation, whereas the Late-RP is related to concrete representation of motor-preparation and execution. The current study aimed to examine whether both the Early-RP and Late-RP were modulated by reward, and if so, whether were related to reward-outcome ERPs.

The third sub-stage of reward-anticipation, feedback-anticipation, occurs after an individual has engaged in the goal-directed action and is now waiting for feedback as to whether their action was successful in obtaining the reward. This process can be quantified through the Stimulus Preceding Negativity (SPN), a negative, pre-Feedback, ERP component at fronto-central sites (Brunia, Hackley, et al., 2011). The SPN is thought to index activity in the insula cortex and to underlie the unresolved expectation preceding feedback of one's action (Böcker, Brunia, & Berg-Lenssen, 1994; Kotani et al., 2009). A number of recent studies have determined that the SPN is more negative when individuals await reward-related feedback (Donkers et al., 2005; Foti & Hajcak, 2012; Fuentemilla et al., 2013; Kotani et al., 2003; Masaki, Takeuchi, Gehring, Takasawa, & Yamazaki, 2006; Moris, Luque, & Rodriguez-Fornells, 2013; Ohgami, Kotani, Hiraku, Aihara, & Ishii, 2004). Nonetheless, similar to the other anticipatory ERPs, it is unknown whether the SPN during reward-anticipation is related to reward-outcome ERPs.

1.2 Reward-Outcome ERPs

We focus on two types of outcome evaluation: reward-evaluation and performance-evaluation. For reward-evaluation, individuals are more motivated to learn the outcome of their behavior on reward trials when their behavioral performance can lead to reward (Van den Berg, Shaul, Van der Veen, & Franken, 2012). As for performance-evaluation, individuals assess whether their prior action was good or bad in meeting their goal of obtaining reward (Miltner, Braun, & Coles, 1997). Different reward-outcome ERPs are more or less sensitive to reward versus performance evaluation. There are at least three reward-outcome ERPs, each occurring at different time windows: the Feedback-Related Negativity (FRN), the P3 locked to the Feedback (FB-P3; Feedback-locked P3), and the Late-Positive Potential (LPP).

The FRN is a negative, frontal deflection ERP peaking around 250 ms post-Feedback onset. The FRN is sensitive to performance-evaluation, such that the FRN is more negative following bad-performance feedback compared to good-performance feedback (Miltner et al., 1997). Thus, the FRN is often viewed as reflecting binary evaluation of positive versus negative performance feedback (Folstein & Van Petten, 2008; Hajcak, Moser, Holroyd, & Simons, 2006; Walsh & Anderson, 2012). A recent study reported an interaction between reward-evaluation and performance-evaluation, such that the magnitude of the FRN difference score between bad-performance versus good-performance feedback was larger for reward trials than no-reward trials (Van den Berg et al., 2012). Unfortunately, because FRN difference-scores were used in this study, it was unclear whether reward-evaluation made the FRN more negative to bad-performance feedback, or made the FRN less negative to good-performance feedback. Recent research supports the latter hypothesis, suggesting that positive (rather than negative) feedback most directly modulates the FRN difference score by making the FRN less negative (Foti, Weinberg, Dien, & Hajcak, 2011; Holroyd, Pakzad-Vaezi, & Krigolson, 2008). Accordingly, we predict that earning money should make the FRN to good-performance feedback less negative (i.e., most positive feedback), while not-earning money should not make the FRN to bad-performance feedback more negative (i.e., most negative feedback). Put differently, we predict that reward-evaluation should make the FRN to good-performance feedback less negative, but should have no effect on the FRN to bad-performance feedback. We further hypothesize that the influence of reward-evaluation on the FRN to good-performance feedback should be related to reward-anticipation ERPs.

The second ERP component present at the reward-outcome stage is the FB-P3 that typically follows the FRN. Similar to the Cue-P3, the FB-P3 is a positive, centro-parietal ERP component peaking around 250-450 ms post-feedback onset. Several studies suggest that the FB-P3 is an indicator of the feedback's motivational saliency (San Martín, 2012), and thus should be primarily influenced by reward-evaluation. For instance, the FB-P3 is sensitive to the magnitude (more vs. less reward) of the feedback (Gu, Wu, Jiang, & Luo, 2011; Sato et al., 2005; Yeung & Sanfey, 2004). Yeung and colleagues (2005) also found a more positive FB-P3 to a feedback of a gambling task when people make a gambling choice themselves compared to when the computer makes a gambling choice for them. Accordingly, we predict that the FB-P3 will be influenced by reward-evaluation, such that reward-trial feedback (i.e., feedback during reward trials, which is the feedback of an action following a reward-anticipation cue) should elicit a more positive FB-P3 than no-reward-trial feedback (i.e., feedback during no-reward-trials, which is the feedback of an action following a no-reward-anticipation cue). We further hypothesize that reward anticipation ERPs will predict the magnitude of the effect that reward-evaluation has on the FB-P3. In contrast to reward-evaluation, the findings are inconsistent as to whether the FB-P3 is sensitive to performance-evaluation (for review see San Martín, 2012). One possible cause of this inconsistency is that the FB-P3 is frequently lumped together with a latter ERP component, the LPP.

Similar to the FB-P3, the LPP is a positive, centro-parietal ERP. However, contrary to the FB-P3, the LPP is more sustained and lasts beyond 450 ms post-stimuli onset (Schupp et al., 2006). Although not typically studied in the context of reward-outcome, the LPP is enhanced by motivationally-salient, high-arousal stimuli in previous studies involving passive-viewing of emotional images (Schupp et al., 2004; Hajcak et al., 2009). The LPP is thought to reflect sustained cognitive-processing or recurring thoughts regarding these stimuli (Dunning & Hajcak, 2009; Hajcak, Dunning, & Foti, 2009). More recently, studies involving reinforcement-learning tasks have investigated a feedback-locked ERP component in similar electrode sites and in a similar time-window (e.g., 400-800 ms) as the LPP (henceforth considered as the LPP) (Borries, Verkes, Bulten, Cools, & Bruijn, 2013; Martin, Appelbaum, Pearson, Huettel, & Woldorff, 2013). In these studies, the LPP predicts behavioral adjustment or a change in behavior in subsequent trials to maximize reward-outcome. Accordingly, we tested whether both reward-evaluation and performance-evaluation influenced the LPP. We predict that the LPP will be influenced by reward-evaluation, such that the reward-trial feedback (i.e., feedback of an action following a reward-anticipation cue) should elicit a more positive LPP than no-reward-trial feedback (i.e., feedback of an action following a no-reward-anticipation cue). We also predict that the LPP will be influenced by performance-evaluation, in that bad-performance feedback (compared to good-performance feedback) should be associated with enhanced LPP positivity, especially if such negative feedback motivates people to improve their performance on subsequent trials to maximize earnings. If the LPP is sensitive to both reward-evaluation and performance-evaluation, and the FB-P3 is sensitive only to reward-evaluation, as predicted above, it would have two important implications. First, this would demonstrate temporal specificity of performance-evaluation between the FB-P3 and LPP time windows. Second this would help resolve inconsistency in the literature regarding the relationship between performance-evaluation and FBP3 (San Martín, 2012), given that the FB-P3 is usually lumped together with the LPP. Finally, as with the FRN and FB-P3, we also investigated whether reward-anticipation ERPs are associated with the reward-outcome LPP.

1.3 Current Study

Modifying the ERP time-estimation paradigm (e.g., Damen & Brunia, 1987; Kotani et al., 2003), participants were instructed to button-press 3.5 s after cue onset and were provided feedback for each trial. On reward trials, participants saw the Reward-Anticipation Cue, and were instructed that they would receive a monetary reward ($ .20) for good-performance (i.e., accurate time-estimation). On no-reward trials participants saw the No-Reward-Anticipation Cue and were instructed that they would receive no monetary reward irrespective of their performance.

The present study has two primary aims. The first aim is to discern ERPs corresponding to different aspects of reward-anticipation (the N2, Cue-P3, RP and SPN) and reward-outcome (the FRN, FB-P3 and LPP) within a single paradigm. Investigating these ERPs within a single paradigm has important implications for clarifying the influence of reward cues on neural activity along the entire temporal scale of reward-processing, from reward-anticipation through reward-outcome. With respect to reward-anticipation ERPs, we examine the precise time-point at which reward-anticipation cues modulate the RP given functional differences between the Early-RP and Late-RP. Additionally, we test the direction by which reward-anticipation cues modulate the N2. If variation in the N2 reflects enhanced cognitive-control in the presence of reward-cues, we predict a more negative N2 for the Reward-Anticipation versus No-Reward-Anticipation Cue. Alternatively, if N2 variation reflects the mismatch from the Reward-Anticipation Cue, we predict a more negative N2 for the No-Reward-Anticipation compared to Reward-Anticipation Cue.

With respect to reward-outcome ERPs, we test whether the interaction between reward-evaluation and performance-evaluation on the FRN is consistent with the account that the FRN is driven by positive, rather than negative, feedback. We predict that reward-trial feedback will make the FRN to good-performance feedback less negative, but have no effect on the FRN to bad-performance feedback. We also examine whether the LPP, but not the FB-P3, is sensitive to performance-evaluation. If true, this would demonstrate temporal-specificity and dissociation in performance-evaluation between the FRN and LPP during reward-outcome.

The second aim of the present study is to examine how ERPs at the three sub-stages of reward-anticipation (reward/no-reward cue-evaluation, motor-preparation and feedback-anticipation) are related to reward-outcome ERPs. We aimed to demonstrate the degree of specificity in the relationship between reward-anticipation and reward-outcome neural activity that is largely ignored in previous research. Examining such relationship would better our understanding of the temporal dynamics of reward-processing in the brain.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Participants

Twenty-three right-handed (< 18, Chapman Handedness Scale; Chapman & Chapman, 1987) native English speakers (10 females, mean age 19.23) at Northwestern University received partial course credit for their participation. Three additional participants were excluded due to excessive artifact. Participants had no neurological history of head injury and were not taking psychotropic medications. After informed consent, participants were informed of the opportunity to earn additional monetary reward based on their performance on the modified time estimation task (see below). The study was approved by the Northwestern Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Time Estimation Task

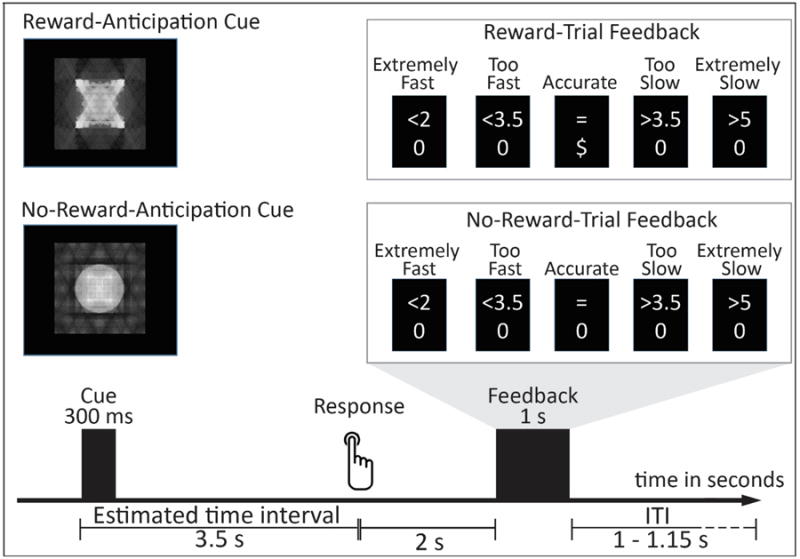

See Figure 1 for a schematic representation of the task. Adapting previous paradigms (e.g., Damen & Brunia, 1987; Kotani et al., 2003), we instructed participants to place their right index figure on a specified button, and press the button with this finger 3.5 s after seeing a Cue. There were two types of Cues: the Reward-Anticipation and No-Reward-Anticipation Cues. Reward trials began with a Reward-Anticipation Cue, and participants were informed they would earn 20 cents for accurate estimates, and receive no monetary reward for inaccurate estimates. The No-Reward trials began with a No-Reward Anticipation Cue, and participants were informed they would, receive no monetary reward irrespective of their performance on these trials. We employed No-Reward-Anticipation trials (as opposed to Punishment-Anticipation trials) for the following reasons. First, No-Reward-Anticipation trials would serve as a control stimulus to estimate non-reward-related factors that may influence ERPs during the time-estimation task (Luck, 2005). Second, comparing the Reward-Anticipation versus No-Reward-Anticipation Cues on the N2 would allow us to directly examine whether a cognitive-control or template-mismatch mechanism underlies the influence of the Reward-Anticipation Cue on the N2. The Reward- and No-Reward-Anticipation Cues were presented on a gray background for 400 ms. These Cues were made from either circle or square shapes (counterbalanced across participants) and were controlled for luminance, contrast, and spatial frequency using the Shine toolbox (Willenbockel et al., 2010).

Figure 1.

Time estimation task. ITI = Inter Trial Interval.

Accurate responses were defined as trials where a button-press occurred within the correct time-window. Following previous studies (e.g., Kotani et al., 2003; Ohgami et al., 2006), the time-window was adapted to control for variance in time-estimation ability among participants. Specifically, the time-window in the following trial would be shortened (or lengthened) by 20 ms if the response in the current trial was (or was not) within the time-window. This method has been found to control accuracy-rate at about 50% (e.g., Kotani et al., 2003; Ohgami et al., 2006). The time-window initially was 500 ms long, centered at 3.5 s in the first practice trial.

Two seconds following the button-press, two lines of Feedback text appeared in the middle of the screen for 1000 ms. The top-line indicated estimation performance and included the following: “=” for a response within the correct time-window, “<2” for an extremely fast response (less than 2 s), “<3.5” for a response slower than 2 s but not within the time-window, “>5” for an extremely slow response (slower than 5 s), and “>3.5” for a response faster than 5 s but not within the time-window. Thus, “=” indicated good-performance, while others indicated bad-performance. The bottom line indicated whether participants won money for that response and included the following: “$” indicated the participant won money (20 cents) for that trial, and “0” indicated the participant did not win money for that trial. Thus, for Reward trials, participants would see “$”for good-performance, and see “0” for bad-performance. For No-Reward trials, participants would see “0” regardless of their performance. Trials were terminated with a random ITI of 1000-1150 ms. Participants were told to do their best across both Reward and No-Reward trials. To incentivize participants' continued attention on both Reward and No-Reward trials, they were told they would receive no earnings if they saw “<2” or “>5” feedback more than 15 times. This ensured that they avoided extremely fast or slow responses

To estimate movement-related potentials that overlapped with anticipation-related potentials in the SPN waveforms, we included Control blocks with minimal feedback (Damen & Brunia, 1994; Kotani & Aihara, 1999; Kotani et al., 2003). During these blocks, participants were again instructed to button-press 3.5 s after seeing a triangle-shaped cue. Unlike the Reward/No-Reward blocks, there was no Feedback regarding the performance or reward outcome except for the extremely fast (“<2”) or slow (“>5”) Feedback, in which participants were instructed to avoid. Consequently, participants did not receive any feedback for most trials in the Control blocks (M = 96.63%). Waveforms following button-presses in the Control blocks represented movement-related potentials with minimal anticipation-related potentials. We subtracted these Control potentials from the potentials obtained following button-presses in the Reward/No- Reward blocks, resulting in a Subtracted SPN (S-SPN) waveform that represented anticipation-related potentials with minimal influence from movement-related potentials. Note that, data analyses focused on the Reward/No-Reward blocks, given that the Control blocks were only used for estimating movement potentials in calculating the S-SPN.

2.3 Procedure

Following consent, EEG electrodes were applied. To familiarize participants with the span of a 3.5-s duration, participants first had the opportunity to listen to two beep sounds 3.5-s apart as many times as they desired. Participants then initiated the Control blocks with no knowledge of the upcoming Reward/No-Reward blocks. The Control blocks consisted of three blocks of 36 trials. Participants were then given instructions regarding the Reward/No-Reward blocks and corresponding cues and feedbacks. Participants were tested on their comprehension of these cues and feedbacks prior to beginning the 30 practice trials in the Reward/No-Reward blocks. The Reward/No-Reward blocks consisted of six blocks of 36 trials. Each of these blocks involved a randomized distribution of Reward and No-Reward trials with a 50/50 split across trial types (i.e., 18 Reward and 18 No-Reward trials). Blocks were separated by breaks of participant-determined length. During these breaks, participants were informed of their earnings and reminded of the meaning of the Cues.

2.4 Electrophysiological Recording

Continuous EEG data with sampling rate at 500 Hz (DC to 100 Hz on-line, Neuroscan Inc.) was collected from inside an electro-magnetic shielded booth. Twenty-four Ag/AgCl scalp electrodes, including F7/3/z/4/8, FC3/z/4, C3/z/4, T3/4, CP3/z/4, P3/z/4, T5/6, O1/z/2 were used. HEOG and VEOG were recorded with four separate eye electrodes. Recordings were referenced on-line to a left mastoid and re-referenced offline to linked mastoids. Impedance was kept below 5 kΩ and 10 kΩ for scalp and eye electrodes, respectively. During the offline analyses, eye movement artifacts were first corrected with PCA algorithms implemented in NeuroScan EDIT (Neuroscan Inc.). Movement-related artifacts were removed manually. EEG was offline bandpass-filtered at .01-30 Hz. Epochs containing artifacts (±75 μV) were rejected.

2.5 Data Analyses: Behavioral Performance

Behavioral performance for each trial was operationalized as the deviation in time estimation from the goal of 3.5 s (i.e., the absolute value of the difference between reaction-time (RT) and 3.5 s) at each trial. Superior estimation performance for one condition over another (i.e., Reward vs No-Reward) was defined as less deviation from the target reaction-time of 3.5 s.

2.6 Data Analyses for Aim 1: ERP ANOVA Analyses

For ANOVA analyses, the Greenhouse-Geisser (G-G) correction was used whenever the sphericity assumption was violated. The Sidak method was applied to control for multiple comparisons when unpacking significant main effects (pairwise comparisons) and interactions (simple interaction/effect analyses).

Extremely fast (less than 2 s, “<2”) or slow (more than 5 s, “>5”) trials were excluded from the ERP analyses as they may reflect lack of attention. ERPs were locked to three events: the Anticipation Cue, Response, and Feedback. From these events, seven ERP components were identified along the temporal scale of reward processing: the N2 and Cue-P3 to the Anticipation Cue, the RP during a period before the Response, the SPN during a period after the Response and right before the Feedback, and the FRN, FB-P3 and LPP to the Feedback.

Anticipation Cue-locked EEG was epoched from -100 to 1000 ms relative to the Reward/No-Reward Anticipation Cue onset, and was baseline corrected using a pre-stimulus (-100 to 0 ms) time-window. Mean-amplitude was used for both the N2 (between 200 and 350 ms at frontocentral sites: Fz, FCz, Cz) and Cue-P3 (between 350 and 500 ms at centroparietal sites: Cz, CPz and Pz). To examine the effect of Reward versus No-Reward on the Anticipation Cue-locked ERP components, separate 2 (Anticipation-Cue Type: Reward vs. No-Reward) × 3 (Site) repeated measure ANOVAs were conducted on N2 and Cue-P3.

Response-locked EEG was epoched from -2000 to 3000 ms relative to the button-press. Prior to baseline correction (using -2000 to -1700 ms time-window), response-locked epochs were removed from slow-wave artifacts by a linear detrend algorithm on a wider (-3000 to 3500 ms) window (for a similar method, see Baker et al., 2012; Goldstein et al., 2006). Following previous recommendation (Brunia, van Boxtel, & Böcker, 2011), a low-pass filter of 10 Hz was further applied on these epochs, resulting in .01-10 Hz data. For the RP, mean amplitude for eight time windows of 200 ms each from -1600 to 0 (movement onset) ms were calculated. This allowed us to determine the specific time window that the Reward-Anticipation Cue started to modulate the RP. Twelve electrode sites along the midline were included in the RP analyses: F3/z/4, FC3/z/4, C3/z/4 and CP3/z/4. To investigate the effect of Reward versus No-Reward Anticipation Cues on the RP, a 2 (Anticipation-Cue Type: Reward vs. No-Reward) × 8 (Time Window) × 12 (Site) repeated measure ANOVA was employed.

For the SPN, to control aforementioned movement-related potentials, averaged waveforms for the Control blocks (see above) were subtracted from averaged waveforms for both Reward and No-Reward trials, producing a S-SPN waveform. The S-SPN then was scored using the mean amplitude from 1600 to 2000 ms (i.e., 400 ms time-window prior to the Feedback onset). For the SPN analysis, we employed the same twelve electrode sites with the RP analysis in a 2 (Anticipation Cue Type: Reward vs. No-Reward) × 12 (Site) repeated measure ANOVA model.

Similar to Anticipation Cue-locked EEG, Feedback-locked EEG was epoched from -100 to 1000 ms relative to the Feedback onset, and baseline corrected using a pre-stimulus (-100 to 0 ms) window. Feedback stimuli were categorized based on 1) Reward-Evaluation, i.e., whether the response feedback followed the Reward-Anticipation Cue (Reward-Trial Feedback) or the No-Reward-Anticipation Cue (No-Reward-Trial Feedback), and 2) Performance-Evaluation, i.e., whether or not the response occurred during the correct time-window: “=” (Good-Performance Feedback) and “<3.5, >3.5” (Bad-Performance Feedback). To isolate the FRN from coinciding ERPs, a peak-to-peak method was used (Holroyd, Nieuwenhuis, Yeung, & Cohen, 2003). Using this peak-to-peak method (as opposed to difference-scores) allowed us to examine the Reward-Evaluation × Performance-Evaluation interaction. We first identified the local maximum positive peak between 160 and 240 ms. We next identified the local maximum negative peak between the local positive peak and 350 ms. These peaks were confirmed by visual inspection. The FRN was then calculated by subtracting the positive-peak amplitude from the negative-peak amplitude at frontal sites: Fz and FCz. The FB-P3 was defined as the mean amplitude between 250 to 450 ms at centroparietal sites: Cz, CPz and Pz. Finally, the LPP was defined as the mean amplitude between 450 and 900 ms at centroparietal sites: Cz, CPz and Pz. For each Feedback-locked ERP (FRN, FB-P3 and LPP), we used a separate 2 (Reward-Evaluation: Reward-Trial vs. No-Reward-Trial) × 2 (Performance-Evaluation: Good-Performance vs. Bad-Performance) × number of Site repeated measure ANOVA.

2.7 Data Analyses for Aim 2: ERP Correlational Analyses

Our second aim involved correlational analyses to examine the relationship between reward-anticipation ERPs and reward-outcome ERPs (for a similar approach, see Moris et al., 2013; Moser, Moran, Schroder, Donnellan, & Yeung, 2013). First, for every ERP component, we calculated a difference score for reward-modulated ERPs, referred to as ΔERPs. Specifically, for reward-anticipation ΔERPs, we subtracted ERPs in No-Reward trials from ERPs in Reward-trials. Accordingly, five indexes were calculated for reward-anticipation ΔERPs: the ΔN2, ΔCue-P3, ΔEarly-RP, ΔLate-RP and ΔS-SPN. Note that for the RP, two indexes were generated to examine temporal specificity of the component: 1) the ΔEarly-RP occurring during the first 200-ms interval at which the Reward RP started to differentiate from the No-Reward RP and 2) the ΔLate-RP occurring during 200 ms just before the movement onset. Similarly, for reward-outcome ERPs, ΔERPs were calculated by subtracting ERPs in the No-Reward trials from ERPs in the Reward trials, but the calculations were done separately for Bad-Performance feedback and for Good-Performance feedback. As such, a total of six reward-outcome ΔERPs were computed: the ΔBad-Performance FRN, ΔGood-Performance FRN, ΔBad-Performance FB-P3, ΔGood-Performance FB-P3, ΔBad-Performance LPP, and ΔGood-Performance LPP. Using ΔERP difference scores allowed us to partially control for non-specific, non-reward-related factors that may affect ERPs (Luck, 2005) and to focus on the influence of reward-related processes The electrodes site for each ΔERP was selected based on previous studies: Fz for the ΔN2 (Potts, 2011), Pz for the ΔCue-P3 (Broyd et al., 2012), Cz for the ΔRP (Bortoletto et al., 2011), Cz for the ΔS-SPN (Kotani, Hiraku, Suda, & Aihara, 2001), FCz for the ΔFRN, Pz for the ΔFB-P3 (Yeung & Sanfey, 2004), and CPz for the ΔLPP (Schupp et al., 2004). Importantly, the sites used for the ΔERP were also the sites that were most strongly influenced by the Reward-Anticipation Cue (i.e., Reward trials vs. No-Reward trials) based on our ANOVA analyses (see Results).

To minimize type-1 error, and to reduce the potential confound of overlapping ERP-components (Luck, 2005), we focused correlational analyses on a priori hypothesized relationships between reward-anticipation ΔERPs (ΔN2, ΔCue-P3, ΔEarly-RP, ΔLate-RP and ΔS-SPN) and reward-outcome ΔERPs (ΔFRN, ΔFB-P3 and ΔLPP, separated by Good-Performance and Bad-Performance Feedback). Specifically, we first conducted zero-order correlations to assess the strength of these relationships. To test whether the correlations varied as a function of Bad-Performance or Good-Performance Feedback, a Williams' (1959) t-test was conducted using SPSS syntax (Weaver & Wuensch, 2013). Additionally, to examine unique and shared effects of reward-anticipation ΔERPs in predicting each reward-outcome ΔERP, multiple-regression analyses were employed. Each reward-outcome ΔERP was utilized as a criterion in separate models. All reward-anticipation ΔERPs that significantly correlated with each reward-outcome ΔERP were simultaneously included as predictors in these models.

3. Results

3.1 Behavioral Results

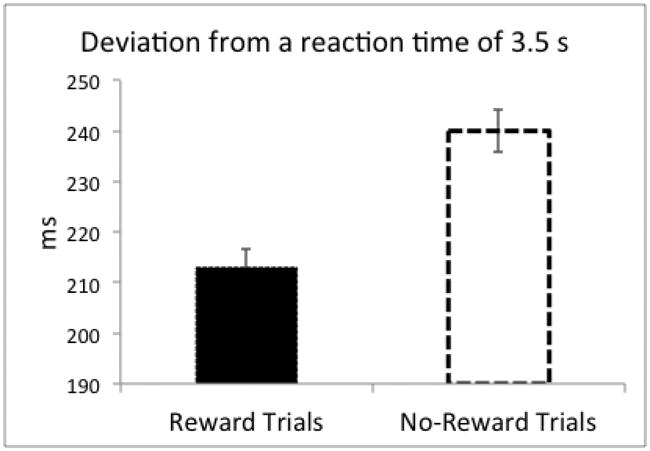

Behavioral data from one subject was lost due to a technical error. Overall, participants estimated 3.5 s quite well (MRT = 3.54 s, SD = .07) and rarely responded outside the 2-5 s time window (M = 0.04%, SD = .20). Given the Accuracy Rate (M = 50.38%, SD = 2.33) closely matched the expected value of 50%, the adaptation of time-window worked effectively. Furthermore, participants' RT deviated from 3.5 s less in Reward trials than No-Reward trials, (t(21) = -3.10, p = .005, Cohen's d = -.32, Figure 2). This suggests that participants' time-estimation performance was better in the Reward trials compared to No-Reward trials.

Figure 2.

Behavioral performance in terms of deviation from a reaction time of 3.5 s (2). Error bars represent ± standard error, corrected for repeated measurement.

3.2 Anticipation Cue-Locked ERP ANOVA Results

On average, 102.43 Anticipation Cue-locked epochs were analyzed for each Anticipation Cue Type condition (Reward-Anticipation Cue versus No-Reward-Anticipation Cue).

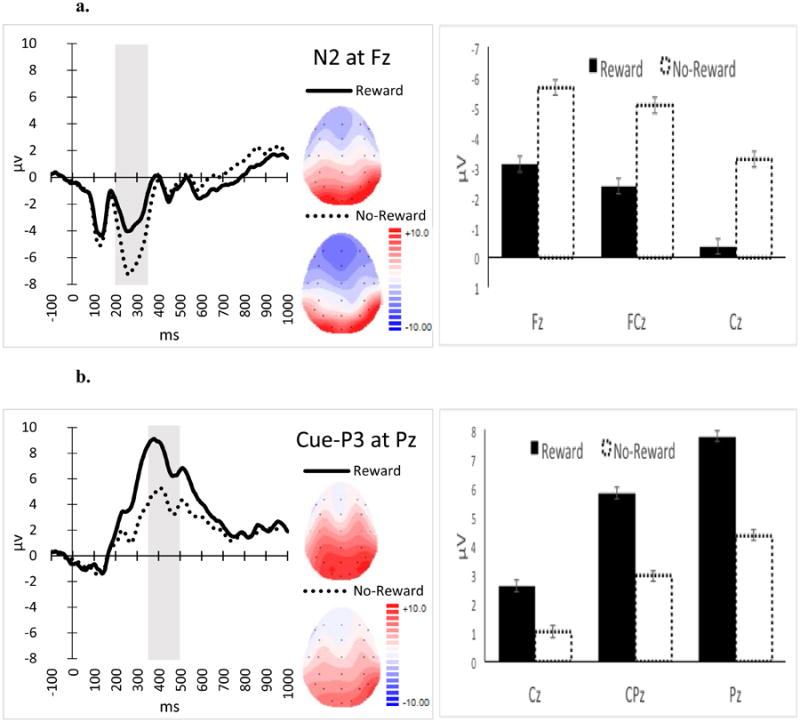

N2 (Figure 3a): There was a significant main effect of Anticipation-Cue Type (F(1, 22) = 27.74, p < .001, ηp2 = .56) and a marginal significant Anticipation-Cue Type × Site (F G-G (1.37, 30.20) = 3.49, p = .059, ηp2 = .14) interaction on the N2. Simple-effect analyses on the interaction indicated that the N2 for the Reward-Anticipation Cue was less negative than for the No-Reward Anticipation Cue across sites (ps < .001), but this effect was more pronounced at Cz, compared to frontal sites (Fz and FCz). The main effect of site was also significant (F G-G (1.15, 25.23) = 43.84, p < .001, ηp2 = .66). Post-hoc pairwise analyses on the main effect of site indicated that the N2 was frontally distributed: most negative at Fz, followed by FCz (p = .005) and then by Cz (p < .001).

Figure 3.

ERP waveforms (left), topographical maps (middle) and average amplitudes (right) for the N2 (3a) and Cue-P3 (3b). The time windows used to measure these components are indicated in gray. Reward = Reward-Anticipation Cue. No-Reward = No-Reward-Anticipation Cue. Error bars represent ± standard error, corrected for repeated measurement.

Cue-P3 (Figure 3b): There was a significant main effect of Anticipation-Cue Type (F(1, 22) = 55.28, p < .001, ηp2 = .72) and a significant Anticipation-Cue Type × Site (F G-G (1.15, 25.32) = 21.07, p < .001, ηp2 = .49) interaction on the Cue-P3 (Figure 2b). Simple effect analyses on the interaction indicated that the Cue-P3 for the Reward-Anticipation Cue was more positive than for the No-Reward-Anticipation Cue across sites (ps < .001), but this effect was more pronounced parietally (i.e., highest at Pz followed by CPz and Cz, respectively). The main effect of Site was also significant (F G-G (1.07, 23.52) = 37.62, p < .001, ηp2 = .63). Post-hoc pairwise analyses on the main effect of site indicated that the Cue-P3 was parietally distributed: most positive at Pz followed by CPz (p < .001) and then by Cz (p < .001).

3.3 Anticipation Response-Locked ERP ANOVA Results

On average, 90.02 Response-locked epochs were analyzed for each Anticipation Cue Type condition (Reward-Anticipation Cue versus No-Reward-Anticipation Cue).

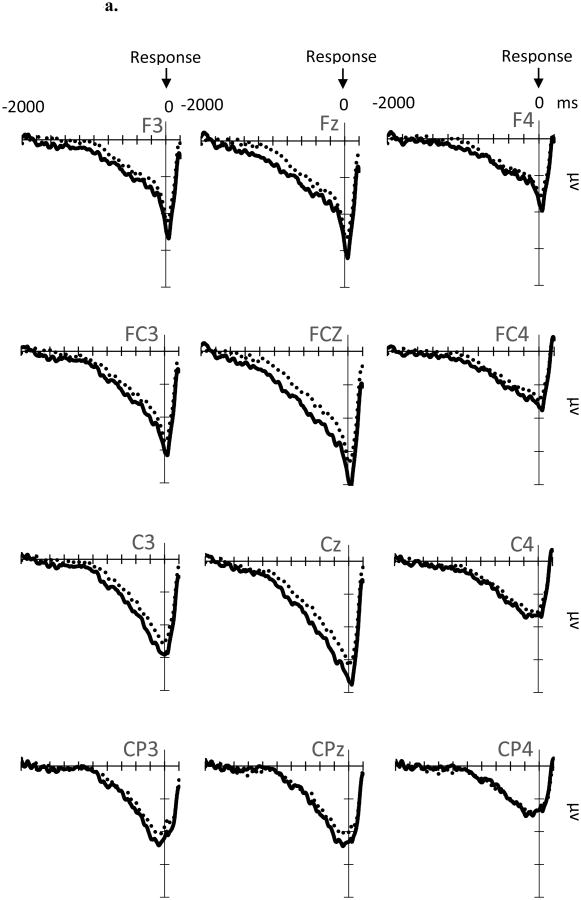

RP (Figure 4a, b): There was a significant main effect of Time Window on RP (F G-G (1.46, 32.14) = 40.86, p < .001, ηp2 = .65). Post-hoc pairwise analyses showed a linear increase in negative activity between each of the two subsequent time windows (Figure 4b), starting from [-1200 to -1000 ms] vs. [-1000 to -800 ms] (p = .03) to [-400 to -200 ms] vs. [-200 to 0 (movement onset) ms] (p's < .001). This suggests an increase in negative activity beginning approximately 1 s prior to the movement onset and peaking just prior to the movement itself. There was also a main effect of Site (F G-G (2.65, 58.24) = 8.64, p < .001, ηp2 = .28). Post-hoc pairwise analyses indicated that the negativity of the RP was distributed more heavily to left frontal-central sites (e.g., FC3, FCz, C3, Cz) compared to right hemispheric sites (e.g., F4, FC4, C4 and CP4, p's < .05). Given that all participants were right handed, this indicates that the RP was more pronounced at electrode sites contralateral to the button press. There was also a significant Time Window × Site interaction (F G-G (4.69, 103.24) = 11.30, p = .046, ηp2 = .11), suggesting that alterations of RP amplitudes were stronger on the left frontal-central sites over time (see topography plots in Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

ERP waveforms (4a), average amplitudes (4b, top) and topographical maps (4b, bottom) for the RP. RP amplitudes and topographical maps are measured at every 200-ms time window. Reward = Reward-Anticipation Cue. No-Reward = No-Reward-Anticipation Cue. Error bars represent ± standard error, corrected for repeated measurement. The time windows at which a simple effect of Anticipation-Cue Type are significant (p ≤ .05) and approaching significant (p ≤ .10) are indicated by asterisks (*) and crosses (†), respectively.

Although the main effect of Anticipation Cue Type (F(1, 22) = 2.62, p = .12, ηp2 = .11) and the Time Window × Anticipation Cue Type interaction on the RP (F G-G(3.03, 66.72) = .89, p = .45, ηp2 = .04) were not significant, there was a significant Site × Anticipation Cue Type two-way interaction (F G-G(3.07, 67.57) = 3.95, p = .03, ηp2 = .15), and a Time Window × Site × Anticipation Cue Type three-way interaction (F G-G(7.37, 162.12) = 2.2, p = .03, ηp2 = .09) on the RP. Simple effect analyses on these interactions revealed that the Site × Anticipation Cue Type interactions were significant at every time window (p's < .03). These Site × Anticipation Cue Type interactions were next investigated further at each Time Window by evaluating the simple main effects of Anticipation Cue Type separately at each Site. We found significantly more negative RPs following the Reward-than No-Reward-Anticipation Cue for most time windows starting from -1000 ms prior to the movement onset at C3, Cz and FCz (for p-values, see Figure 4b). This simple Reward effect also approached significance (p's < .1) in some of these time windows at adjacent electrodes, including FC3 and Fz. Collectively, these results suggest that as early as 1 s prior to the button press, the Reward-Anticipation Cue enhanced the RP at the left fronto-central sites, which was contralateral to the movement.

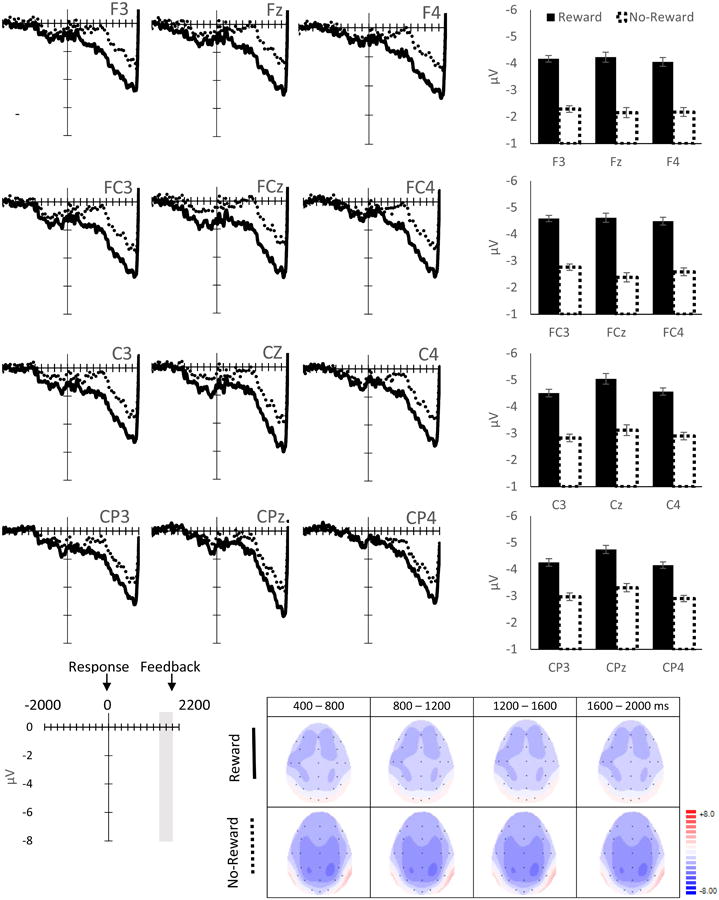

S-SPN (Figure 5): There was a significant main effect of Anticipation Cue Type (F(1, 22) = 40.80, p < .001, ηp2 = .65) and an Anticipation Cue Type × Site interaction (FG-G(3.47, 76.25) = 4.80, p = .003, ηp2 = .18) on the S-SPN. Simple effect analyses on this interaction indicated that the S-SPN for the Reward-Anticipation Cue was more negative than for the No-Reward-Anticipation Cue across sites (ps < .001), but this effect was less pronounced at central-parietal sites (CP3/z/4) compared to other sites. There was no main effect of Site (FG-G (2.61, 57.45) = 1.80, p < .16, ηp2 = .076). In contrast to the RP, we found no laterality difference in the S-SPN between the Reward- and No-Reward-Anticipation Cues. (Note that analyses of the SPN without subtraction of the control waveforms from the control blocks yielded similar results).

Figure 5.

ERP waveforms (top-left), average amplitudes (top-right) and topographical maps (bottom-right) for the S-SPN. S-SPN amplitudes are measured from 400 ms pre-feedback to the feedback onset (1600 to 2000 ms after the movement onset). This time window is indicated in gray. Topographical maps are plotted at every 400-ms time window from 400 ms after the movement onset. Reward = Reward-Anticipation Cue. No-Reward = No-Reward-Anticipation Cue. Error bars represent ± standard error, corrected for repeated measurement.

3.4 Feedback-Locked ERP ANOVA Results

On average, 49.6 Feedback-locked epochs were analyzed for each Reward-Evaluation (Reward-Trial Feedback vs. No-Reward-Trial Feedback) × Performance-Evaluation condition (Good-Performance Feedback vs. Bad-Performance Feedback).

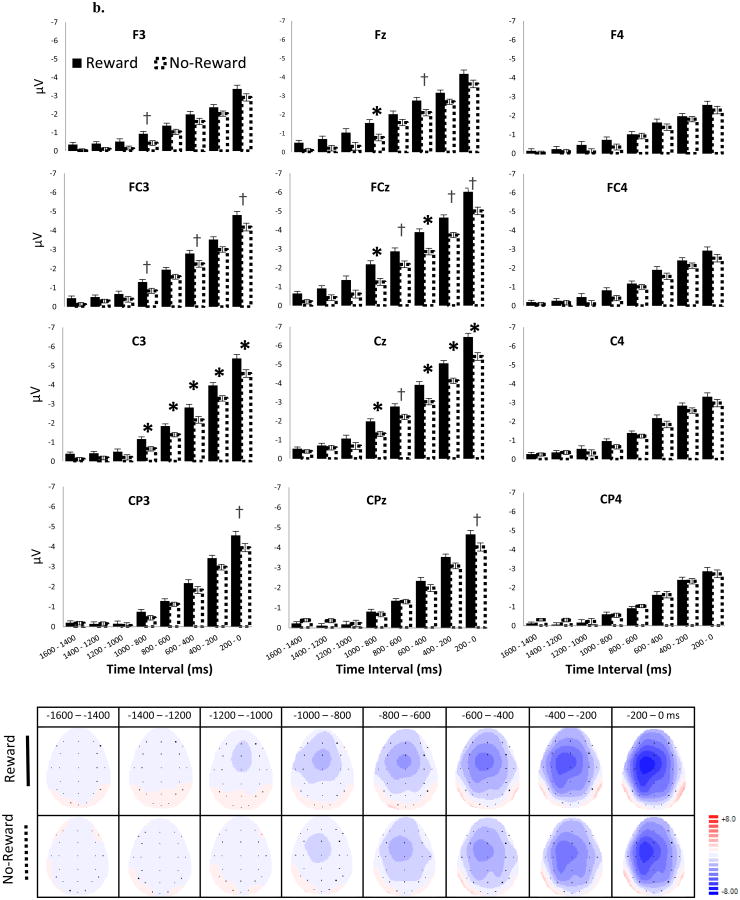

FRN (Figure 6): There was a significant main effect of Reward-Evaluation (F(1, 22) = 4.15, p = .05, ηp2 = .16), indicating that the Reward-Trial Feedback elicited a less negative FRN than the No-Reward-Trial Feedback. Similarly, there was a significant main effect of Performance-Evaluation (F(1, 22) = 10.01, p = .005, ηp2 = .31), indicating that Bad-Performance Feedback led to a more negative FRN than Good-Performance Feedback. There was also a significant main effect of Site (F(1, 22) = 29.80., p < .001, ηp2 = .58), indicating that the FRN was more negative at Fz than at FCz. These main effects were qualified by a significant Reward-Evaluation × Performance-Evaluation × Site three-way interaction (F(1, 22) = 5.09, p = .03, ηp2 = .19). To follow up this three-way interaction, simple interaction analyses were conducted at each of the sites, showing that the Reward-Evaluation × Performance-Evaluation interaction was not significant at Fz (F(1, 22) = 1.85, p = .19, ηp2 = .08), but marginally significant at FCz (F(1, 22) = 4, p = .058, ηp2 = .15). Further simple-effect analyses were used to follow up this two-way interaction at FCz, revealing that Reward-Trial Feedback significantly reduced the negativity of the FRN for Good-Performance Feedback (p = .005), but did not have a significant effect on Bad-Performance Feedback (p = .87).

Figure 6.

ERP average amplitudes (left) and waveforms (right) for the FRN. The time windows used to measure FRN are indicated in gray. Error bars represent ± standard error, corrected for repeated measurement.

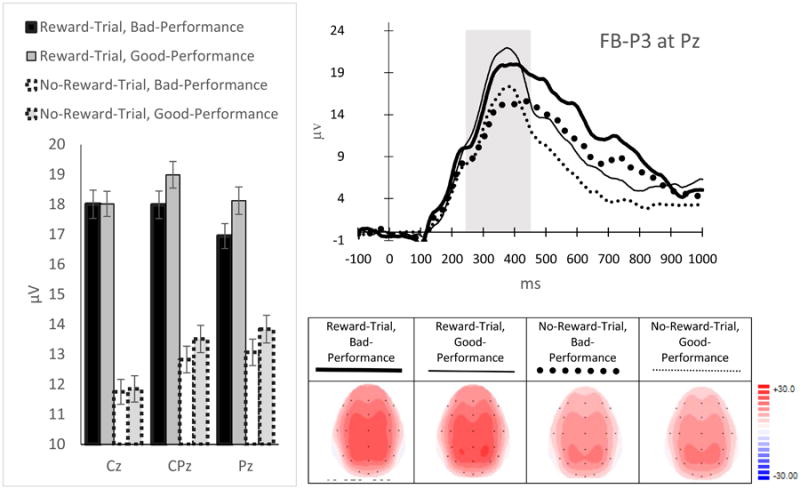

FB-P3 (Figure 7): There was a main effect of Reward-Evaluation on the FB-P3 (F(1, 22) = 57.74, p < .001, ηp2 = .72). Although the main effect of Site was not significant (FG-G (1.09, 23.88) = 1.29, p = .27, ηp2 = .06), the Reward-Evaluation × Site interaction (FG-G(1.12, 24.64) = 39.72., p < .001, ηp2 = .64) was significant. Simple effect analyses indicated that the FB-P3 for Reward-Trial Feedback was more positive than for No-Reward-Trial Feedback across sites (p's < .001), but the effects were more pronounced at Cz, followed by CPz, and Pz, respectively. There was no main effect of Performance-Evaluation (F(1, 22) = .98, p = .33, ηp2 = .04). Although there was a significant Performance-Evaluation × Site interaction (FG-G(1.26, 27.70) = 9.94, p = .002, ηp2 = .31), simple effect analyses on this interaction did not reveal an effect of Performance-Evaluation at any sites: Cz (p = .90), CPz (p = .20) and Pz (p = .13). Other effects, including the Reward-Evaluation × Performance-Evaluation interaction (p = .5) and the three-way interaction (p = .3) were not significant.

Figure 7.

ERP magnitudes (left), waveforms (top-right) and topographical maps (bottom-right) for the FB-P3. The time windows used to measure the FB-P3 are indicated in gray. Error bars represent ± standard error, corrected for repeated measurement.

FB-P3 (Figure 7): There was a main effect of Reward-Evaluation (F(1, 22) = 57.74, p < .001, ηp2 = .72 Although the main effect of Site was not significant (FG-G (1.09, 23.88) = 1.29, p = .27, ηp2 = .06), the Reward-Evaluation × Site interaction (FG-G(1.12, 24.64) = 39.72., p < .001, ηp2 = .64) was significant. Simple effect analyses indicated that the FB-P3 for Reward-Trial Feedback was more positive than for No-Reward-Trial Feedback across sites (p's < .001), but the effects were more pronounced at Cz, followed by CPz, and Pz, respectively. There was no main effect of Performance-Evaluation (F(1, 22) = .98, p = .33, ηp2 = .04). Although there was a significant Performance-Evaluation × Site interaction (FG-G(1.26, 27.70) = 9.94, p = .002, ηp2 = .31), simple effect analyses on this interaction did not reveal an effect of Performance-Evaluation at any sites: Cz (p = .90), CPz (p = .20) and Pz (p = .13). Other effects, including the Reward-Evaluation × Performance-Evaluation interaction (p = .5) and the three-way interaction (p = .3) were not significant.

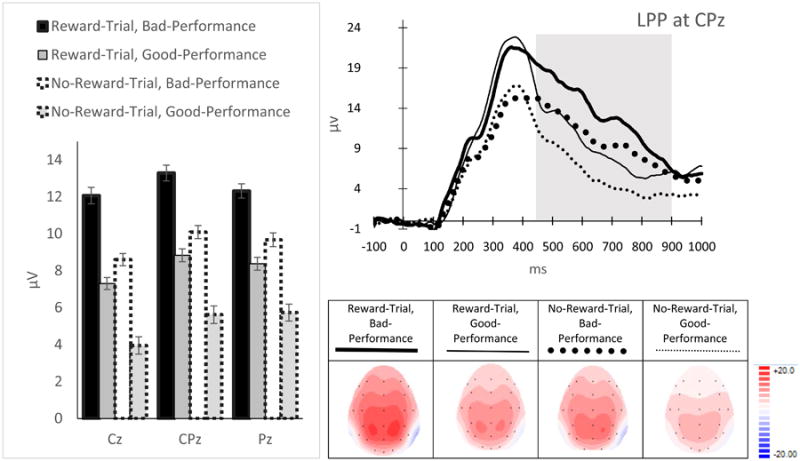

LPP (Figure 8): There was a main effect of Reward-Evaluation (F(1, 22) = 37.28, p < .001, ηp2 = .63) and a Reward-Evaluation × Site interaction (FG-G(1.29, 28.36) = 9.50., p = .003, ηp2 = .3) on the LPP. Simple effect analyses on this interaction indicated that the LPP was more positive for Reward-Trial Feedback than No-Reward-Trial Feedback across sites (p's < .001), but that the effect was more pronounced at Cz and CPz relative to Pz. There was also a main effect of Performance-Evaluation (F(1, 22) = 65.28, p < .001, ηp2 = .75) and a Performance-Evaluation × Site interaction (FG-G(1.28, 28.18) = 5.78., p = .017, ηp2 = .21) on the LPP. Simple effect analyses indicated that the LPP for Bad-Performance Feedback was larger than for Good-Performance Feedback across sites (p's < .001), but the effects were more pronounced at Cz and CPz relative to Pz. There was also a significant main effect of Site (FG-G(1.16, 25.57) = 6.13., p = .017, ηp2 = .22). Post-hoc pairwise analyses on the main effect of site indicated that the LPP was largest at CPz, which was significantly more positive than the LPP at Cz (p < .002). Similar to the FB-P3, the Reward-Evaluation × Performance-Evaluation interaction (p = .8) and the three-way interaction (p = .9) on the LPP were not significant.

Figure 8.

ERP magnitudes (left), waveforms (top-right) and topographical maps (bottom-right) for the LPP. The time windows used to measure the LPP are indicated in gray. Error bars represent ± standard error, corrected for repeated measurement.

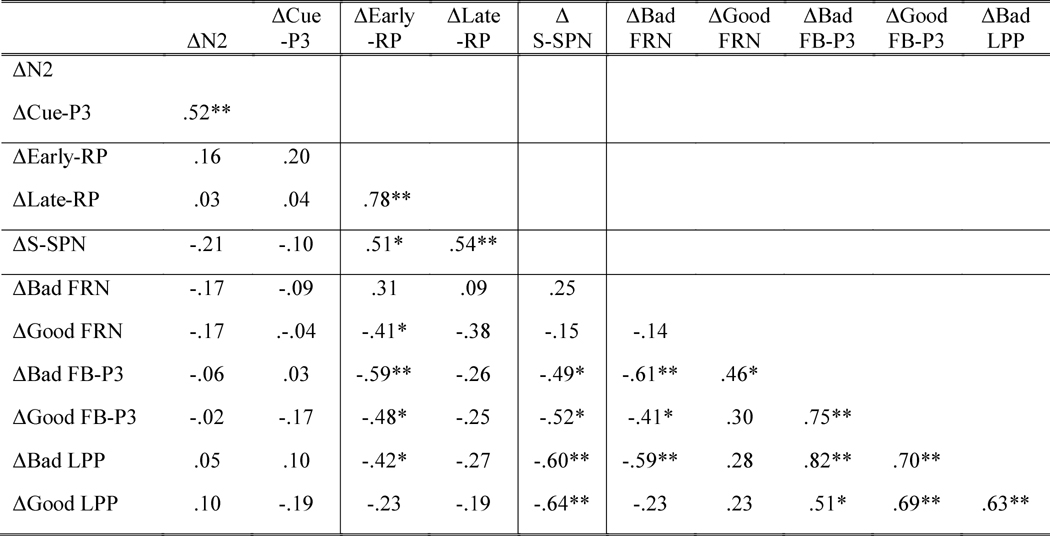

3.5 Results for Correlations between Reward-Anticipation and Reward-Outcome ERPs

See Table 1 for a complete listing of the correlations between ΔERP. The ΔEarly-RP was calculated using the RP during -1000 to -800 ms prior to movement onset, the time window at which the RP in Reward trials started to differentiate from the RP in No-Reward trials. The ΔLate-RP, on the other hand, was calculated using the RP during -200 ms to movement onset.

Table 1. Zero-Order Correlations between ΔERPs.

Note. ΔERPs were calculated by subtracting No-Reward ERPs from Reward ERPs. Table borders were used to separate ERPs that occurred at different reward-anticipation and reward-outcome stages. More negative scores for the N2, RP, SPN and FRN indicate greater ERP amplitudes since these components represent negative-going waveforms. Time windows used for calculating ΔEarly-RP and ΔLate-RP were -1000 to -800 ms and -200 to movement onset ms, respectively. Bad = Bad-Performance; Good = Good-Performance;

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01.

Note also that both ΔEarly-RP and ΔLate-RP had positive correlations with feedback anticipation ΔERP, ΔS-SPN (Supplementary Figure 1). Because the two correlations (ΔEarly-RP & ΔS-SPN and ΔLate-RP & ΔS-SPN) were not different from each other (t(20) = -.28, p = .78), this suggests that enhancement of motor preparation by reward (ΔRP) was related to the enhancement of feedback anticipation (ΔS-SPN), irrespective of RP time windows.

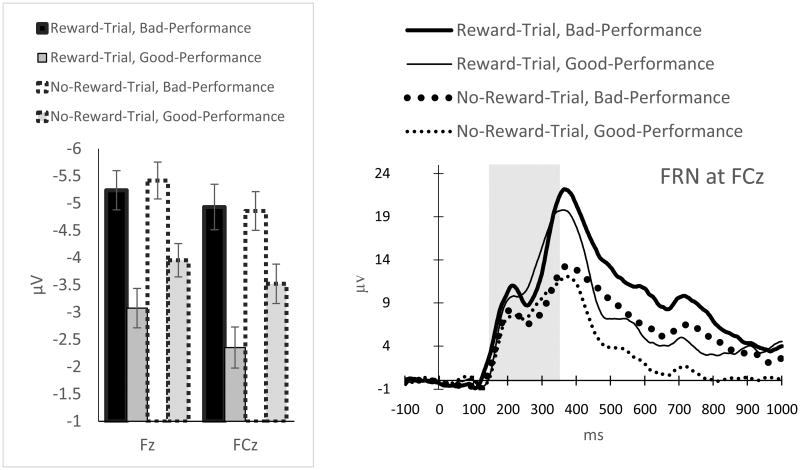

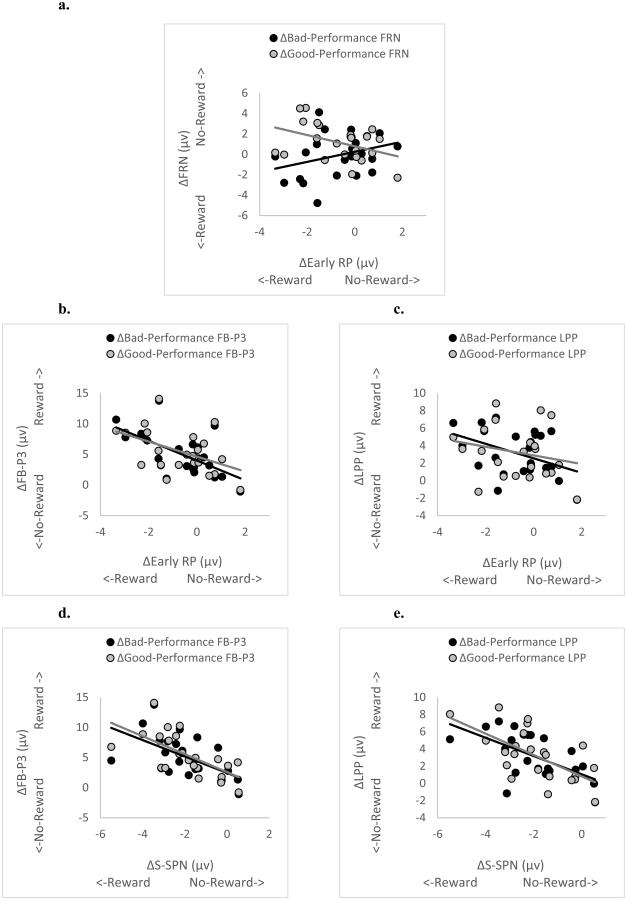

Anticipation Cue ΔERPs (including the ΔN2 and ΔCue-P3) were not correlated with any reward-outcome ΔERPs (p's > .33). Relationships between motor-preparation ΔERPs and reward-outcome ΔERPs (including the ΔFRN, ΔFB-P3, and ΔLPP) were specific to the Early-RP time-window. The correlations between the ΔLate-RP and reward-outcome ΔERPs were small and non-significant (p's > .21) except for the correlation with the ΔGood-Performance FRN which approached significance (r(21) = -.38, p = .08). The ΔEarly-RP, by contrast, was correlated with many reward-outcome ΔERPs. First, there was a significant negative relationship between the ΔEarly-RP and the ΔGood-Performance FRN, and a non-significant positive relationship between the ΔEarly-RP and the ΔBad-Performance FRN (Figure 9a). Because these two correlations were significantly different from each other (t(20) = -2.43, p = .03), this indicates that the enhancement of early motor-preparation by the Reward-Anticipation Cue (ΔEarly-RP) was uniquely associated with the ΔFRN during Good-Performance feedback, but not during Bad-Performance Feedback. Specifically, during Good-Performance Feedback, individuals with a more negative ΔEarly-RP had a less-negative FRN to the Reward-Trial (compared to the No-Reward-Trial) Feedback.

Figure 9.

Scatterplots of the correlations between ΔERPs (ERPs in Reward Trials minus ERPs in No-Reward Trials): ΔEarly-RP and ΔFRN (9a), ΔEarly-RP and ΔFB-P3 (9b), ΔEarly-RP and ΔLPP (9c), ΔS-SPN and ΔFB-P3 (9d), and ΔS-SPN and ΔLPP (9e).

The ΔEarly-RP was also negatively correlated with the ΔFB-P3 and ΔLPP. Because the RP represents negative-going waveforms while the FB-P3 and LPP represent positive-going waveforms, these negative correlations reflect corresponding activity. The ΔEarly-RP was negatively related with both the ΔGood-Performance FB-P3 and ΔBad-Performance FB-P3 (Figure 9b), and these two correlations were not significantly different from each other (t(20) = .87, p = .40). This suggests that the larger the enhancement of the ΔEarly-RP by the Reward-Anticipation Cue, the larger the ΔFB-P3 is irrespective of performance-evaluation (i.e., Good-Performance vs. Bad-Performance feedbacks). The ΔEarly-RP was negatively correlated with the ΔBad-Performance LPP, but not with the ΔGood-Performance LPP (Figure 9c), although these two correlations were in the same negative direction and were not significantly different from each other (t(20) = -1.11, p = .28). Thus, we can only conclude that the enhancement of the ΔEarly-RP by the Reward-Anticipation Cue was associated with a larger increase in the ΔBad-Performance LPP.

In contrast to the ΔEarly-RP, there was no relationship between the feedback-anticipation ΔS-SPN and the ΔFRN and the feedback-anticipation ΔS-SPN was not sensitive to ΔFRN performance evaluation. Specifically, the ΔS-SPN was correlated with the ΔFB-P3 and ΔLPP but neither ΔGood-Performance nor ΔBad-Performance FRNs (p's > .26). Moreover, the ΔS-SPN was negatively correlated with both the ΔGood-Performance and ΔBad-Performance FB-P3s at a similar strength (Figure 9d; t(20) = .21, p = .84). Furthermore, the ΔS-SPN also had a comparable negative relationships to both the ΔGood-Performance and ΔBad-Performance LPPs (Figure 9e; t(20) = .23, p = .82). Similar to the RP, the SPN has a negative-going waveform, thus these negative correlations between the ΔS-SPN and the positive-going ΔFB-P3 and ΔLPP indicate corresponding activity. This suggests that the enhancement of the ΔS-SPN by the Reward-Anticipation Cue was associated with increases in both the ΔFB-P3 and ΔLPP locked to the Feedback, irrespective of Good-Performance or Bad-Performance Feedback.

Because two reward-anticipation ΔERPs (ΔEarly-RP and ΔS-SPN) were both correlated with reward-outcome ΔERPs (ΔFB-P3 and ΔLPP), multiple-regression analyses were used to assess for combined versus unique effects of the ΔEarly-RP and ΔS-SPN in predicting each reward-outcome ΔERP (see Table 2). In these multiple-regression analyses, we calculated the ΔFB-P3 and ΔLPP by subtracting ERPs in No-Reward trials from ERPs in Reward trials collapsing across Bad-Performance and Good-Performance Feedback. This is because 1) we focused on reward modulation (i.e., Reward-Evaluation, not Performance-Evaluation), 2) there were no interactions between Reward-Evaluation and Performance-Evaluation for either FB-P3 or LPP, and 3) the correlations between the two reward-anticipation ΔERPs and the two reward-outcome ΔERPs were similar across Bad-Performance and Good-Performance feedbacks. When using both the ΔEarly-RP (β = -.42, p = .05) and ΔS-SPN (β = -.32, p = .13) to predict the ΔFB-P3, only the ΔEarly-RP remained significant.2 In contrast, when using both the ΔEarly-RP (β = .03, p = .86) and ΔS-SPN (β = -.65, p = .004) to predict the ΔLPP, only the ΔSPN remained significant. Together with the zero-order correlation results, this indicates that the ΔEarly-RP was related more to the early phase of reward-outcome (including, the ΔGood-Performance FRN and ΔFB-P3) while the ΔSPN was related more to the later phase (i.e., the ΔLPP).

Table 2. Multiple Regression Analysis.

| B | SE B | β | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 - ΔFB-P3 as the criterion | ||||

| Constant | 2.21 | .89 | .02 | |

| ΔEarly-RP | -.99 | .48 | -.42 | .05 |

| ΔS-SPN | -.67 | .43 | -.32 | .13 |

|

| ||||

| Model 2- ΔLPP as the criterion | ||||

| Constant | .96 | .71 | .19 | |

| ΔEarly-RP | .07 | .38 | .03 | .86 |

| ΔS-SPN | -1.01 | .34 | -.65 | .004 |

Note. R2 = .41 (p = .006) for Model 1; R2 = .40 for Model 2 (p = .006); Collinearity statistics (Tolerance = .74, VIF = 1.35) indicated that multicollinearity between the predictors was not a concern; The criteria (including, the ΔFB-P3 and ΔLPP) were calculated by subtracting ERPs in No-Reward trials from ERPs in Reward trials, collapsing across Bad-Performance and Good-Performance epochs.

4. Discussion

During Reward Trials (relative to No-Reward Trials), participants' ERPs were altered at each specific sub-stage of reward-anticipation (the N2, Cue-P3, RP and SPN) and reward-outcome (the FRN, FB-P3 and LPP). These alterations in ERPs during Reward Trials were accompanied by greater consistency in time-estimation performance. Accordingly, we were able to examine and isolate unique aspects of reward-anticipation and reward-outcome related neural activity within a single paradigm. This allows us to clarify the role of reward-related stimuli on ERPs along the entire temporal scale of reward-processing. More importantly, isolating reward-related neural activity along the temporal scale allowed us to examine the nature of the relationship between reward-anticipation and reward-outcome ERPs that have largely been ignored in previous research. In brief, we found that reward-anticipation ERPs at the early phase of motor-preparation (ΔEarly-RP) and feedback anticipation (ΔSPN) were associated with reward-outcome ERPs. By contrast, reward/no reward-cue evaluation (ΔN2, ΔCue-P3) and later phase motor preparation (ΔLate-RP) were not associated with reward-outcome ERPs.

4.1 Reward-Anticipation ERPs

At the anticipation cue-evaluation stage, we report that the Reward-Anticipation Cue, relative to the No-Reward-Anticipation Cue, reduced the N2 but enhanced the Cue-P3. This enhanced Cue-P3 to the Reward-Anticipation cue is consistent with previous research (Broyd et al., 2012; Goldstein et al., 2006; Ramsey & Finn, 1997; Santesso et al., 2012), highlighting the role of the Cue P3 in processing motivationally salient stimuli (Carrillo-de-la-Peña & Cadaveira, 2000; Kleih, Nijboer, Halder, & Kübler, 2010). Although the N2 result is consistent with previous studies that found a smaller N2 for reward, than for punishment, cues (Potts, 2011; Santesso et al., 2012), our findings allow for a more nuanced interpretation. Variation in N2 amplitude was previously interpreted as stemming from enhanced cognitive control in order to avoid punishment (Potts, 2011). However, in the current study, punishment was not a possibility. Thus, if the cognitive-control interpretation of the N2 is correct, we would expect increased cognitive-control for the Reward Anticipation, over No-Reward Anticipation, Cue in order to obtain monetary reward. Instead, we argue that the N2 may reflect a mechanism other than cognitive-control, namely template mismatch (Folstein & Van Petten, 2008). Specifically, the Reward-Anticipation Cue is more desired because it indicates an opportunity to win monetary rewards. Accordingly, it may create a bias expectation, rendering it an expected or desired “template” in this task. The elevated N2 to the No-Reward-Anticipation Cue, in turn, may reflect a mismatch to this expectation-based template. Note that another possible explanation is that the Reward-Anticipation Cue generated a more positive N2 in a manner that is similar to when a positive feedback cue leads to a less negative FRN (see below). This possible explanation has previously been proposed as a “reward-related positivity” phenomenon that applies to both cue and feedback stimuli (Holroyd, Krigolson, & Lee, 2011). However, the non-significant correlation between the ΔN2 and ΔFRN (see below) does not support this explanation, as one would expect these two ERPs to correlate with each other if they were modulated by the same reward-related positivity mechanism. Accordingly, we argue that variation in the N2 likely reflects a template-mismatch, as opposed to a reward-related positivity. Future research, however, is needed to more fully test this hypothesis.

At the motor-preparation stage, we report, for the first time, that Reward-Anticipation Cues result in a more negative RP preceding a goal-directed movement. The effect of the Reward-Anticipation Cue on the RP is consistent with a classic experiment in which a heightened RP was observed when monetary reward was randomly given following a voluntary, self-paced movement (McAdam & Seales, 1969). It also concurs with recent RP research showing that movement goals (i.e., moving after a certain duration as opposed to freely moving) elevates the RP (Baker et al., 2012). More importantly, we demonstrate the specific time point at which the Reward-Anticipation Cue enhances motor-preparation processes.4 Judging by the increase of RP following the Reward-Anticipation Cue, the enhancement of motor-preparation by the Reward-Anticipation Cue occurs as early as 1 s before movement onset at the central regions contralateral to the movement. This suggests that reward-enhancement of RP takes place during both what is typically categorized as the early RP (i.e., earlier than 600 ms prior to the movement) and the late RP (Bortoletto et al., 2011; Kutas & Donchin, 1980; Shibasaki et al., 1980). Based on this duration, it is likely that the reward-enhanced RP was generated both by areas associated with the early RP, such as the supplementary motor area (SMA) and the pre-SMA, as well as areas associated with the late RP, including the contralateral M1 and lateral premotor cortex (Cunnington et al., 2002; Shibasaki & Hallett, 2006). Functionally, this means monetary reward enhanced both abstract representation of motor-preparation (Early-RP) and concrete representation of motor-preparation and execution (Late-RP) (Shibasaki & Hallett, 2006).

At the feedback-anticipation stage, we replicate a number of recent studies showing that the SPN is more negative when individuals expect reward-related feedback (Donkers et al., 2005; Foti & Hajcak, 2012; Fuentemilla et al., 2013; Kotani et al., 2003; Masaki et al., 2006; Moris et al., 2013; Ohgami et al., 2004). Contrary to previous research, we found no evidence of right hemisphere dominance in the topographical distribution that traditionally characterizes the SPN (Brunia, Hackley, et al., 2011) for both the Reward and No-Reward trials. Previous studies of the SPN using monetary-reward feedback typically show right hemisphere dominance when the SPN is followed by no-reward-trial feedback, but show no hemispheric differences when SPN is followed by reward-trial feedback (Chwilla & Brunia, 1991; Kotani et al., 2003; Ohgami et al., 2004).3 This discrepancy may be due to differences in experimental designs as these previous studies often employed a block design to separate reward-feedback conditions, whereas in our study, Reward and No-Reward trials were intermixed within the same block. Thus, anticipating No-Reward-Trial feedback in the current study may resemble anticipating reward-trial feedback in previous studies. This is because, in the present study, learning the accuracy of their time estimation in the No-Reward Trials gave participants a sense of the precision of their estimation skill, and potentially allowed them to earn more reward on subsequent reward trials. Future research is needed to examine this logic and assess this hemispheric pattern in event-related versus block designs. Collectively, our findings highlight that the SPN plays a role in anticipating reward-related feedback, and that the neural activity underlying such anticipation is enhanced by the presence of motivationally-salient Reward-Anticipation Cues (Brunia, Hackley, et al., 2011).

4.2 Reward-Outcome ERPs

At the reward-outcome stage, we found that different characteristics of Reward-Evaluation and Performance-Evaluation modulated the three examined ERP components: the FRN, FB-P3 and LPP. First, the FRN was sensitive to Performance-Evaluation, such that it was more negative for Bad-Performance (than for Good-Performance) Feedback, consistent with most FRN studies (Miltner et al., 1997; Walsh & Anderson, 2012). Moreover, our FRN results replicate a recent time-estimation study (Van den Berg et al., 2012), showing that the FRN difference-score between Bad-Performance and Good-Performance Feedback was larger during Reward Trials than No-Reward Trials. Because we examined the FRN separately for Bad-Performance and Good-Performance feedback (as opposed to just relying on the difference -score), we were able to further clarify the direction of reward-modulation. In particular, Reward-Evaluation at FCz further diminished FRN negativity to Good-Performance Feedback, but had no influence on FRN amplitude to Bad-Performance Feedback. Collectively, this suggests that (1) having the opportunity to win monetary reward and actually obtaining the reward (i.e., the most positive Feedback) led to a less negative FRN, and (2) having the same opportunity, but ending up not receiving any reward (i.e., the most negative Feedback) did not lead to any increase in FRN negativity. These two FRN accounts are consistent with a recent theory of the FRN. This theory posits that positive feedback evokes a positive deflecting waveform that is superimposed on the negative deflecting waveform of the FRN (therefore reducing its amplitude) and that, consequently, variation in the FRN between positive and negative feedback may be driven by positive (as opposed to negative) feedback cues (Foti et al., 2011; Holroyd et al., 2008).

Second, we found that Reward-Evaluation modulated the FB-P3 such that Reward-Trial Feedback enhanced the FB-P3 relative to the No-Reward-Trial Feedback. However, there was no effect for Performance-Evaluation on the FB-P3. This is consistent with previous findings that the FB-P3 is independently sensitive to the motivational salience of feedback but not performance-feedback (Gu et al., 2011; Sato et al., 2005; Van den Berg, Franken, & Muris, 2011; Yeung & Sanfey, 2004). Thus, our findings support the notion that there are independent neural systems that vary in their sensitivity to different characteristics of feedback information and that operate at different time points in the processing stream. For example, whereas the FRN was modulated by the interaction between Performance-Evaluation and Reward-Evaluation in the present study, the FB-P3 was particularly sensitive to Reward-Evaluation, but not Performance-Evaluation.

Finally, unlike the FRN and FB-P3, we found that Reward-Evaluation and Performance-Evaluation independently influenced the LPP such that both Reward-Feedback and Bad-Performance Feedback enhanced the LPP, and the two did not interact with each other. A more positive LPP following Reward-Trial Feedback is consistent with previous research showing that the LPP is sensitive to motivationally salient, high-arousal stimuli (Cuthbert, Schupp, Bradley, Birbaumer, & Lang, 2000; Schupp et al., 2000; Schupp et al., 2004). We interpret our LPP results as reflecting sustained cognitive-processing following Reward-Trial Feedback (Dunning & Hajcak, 2009; Hajcak et al., 2009). Additionally, a more positive LPP to Bad-Performance Feedback is in line with the documented link between the LPP and behavioral adjustment. For instance, previous studies (Borries et al., 2013; Martin et al., 2013) report a more positive LPP following feedback signaling behavioral switching to maximize earnings. Likewise, in our case Bad-Performance Feedback may have signaled the need for participants to improve their time estimation in order to earn more money, which, in turn, may have elevated the LPP. Collectively, we suggest that participants had sustained cognitive-processing following both Reward-Feedback and Bad-Performance Feedback, and that both these psychological processes enhanced the LPP.

To summarize our reward-outcome findings, we observed that different aspects of outcome evaluation had unique effects on outcome ERPs along the temporal scale: the FRN was modulated by the interaction between Performance-Evaluation and Reward-Evaluation, the FB-P3 was modulated primarily by Reward-Evaluation, and the LPP was independently modulated by both Performance-Evaluation and Reward-Evaluation. It is worth mentioning that previous research typically combined the FB-P3 and LPP into a single P3 component. This approach may have generated inconsistent findings on the role of the FB-P3 in Performance-Evaluation (San Martín, 2012). By separating this ERP component into early (FBP3) and late (LPP) time windows, we argue that we provide a more nuanced view of the P3. Specifically, we demonstrate that Performance-Evaluation uniquely influenced the late, but not early, portion of what typically considered as the P3 time window. Future studies are needed to examine whether our separation of the P3 into the FB-P3 versus the LPP is specific to a situation in which performance-related feedback signals people to improve their subsequent actions as in the present study. That is, it is still unclear whether Performance-Evaluation would influence the LPP if the current-trial action has a weaker relationship with the subsequent-trial action, e.g. when gambling with a slot machine.

4.3 Relationship between Reward-Anticipation and Reward-Outcome ERPs

The second aim of the present study was to examine the relationship between reward-anticipation and reward-outcome ERPs. We demonstrate an important degree of specificity in these relationships. First, the relationship between motor-preparation ΔERPs during reward anticipation and reward-outcome ΔERPs was largely specific to the early phase of motor-preparation. While the ΔEarly-RP was significantly correlated with multiple reward-outcome ΔERPs, the correlations between the ΔLate-RP and reward-outcome ΔERPs were mostly small and non-significant, with the one exception being the correlation with the ΔGood-Performance FRN that approached significance (p = .08). This means that the abstract-representation of motor-preparation (ΔEarly-RP) during reward anticipation, as compared to the concrete representation of motor-preparation and execution (ΔLate-RP), was more strongly related to the intensity of one's reaction to the rewarding outcome of an action.

Furthermore, the enhanced ΔEarly-RP following the Reward-Anticipation Cue was uniquely associated with a reduced ΔFRN only when the feedback revealed Good-Performance. This finding is in line with our main effect showing that Reward-Evaluation reduced the negativity of the FRN to Good-Performance Feedback but did not modulate the negativity of the FRN to Bad-Performance Feedback. Thus, enhanced early motor-preparation during reward-anticipation appears to be uniquely associated with how much Reward-Evaluation reduced the FRN to Good-Performance Feedback.

By contrast, the relationship between the early motor-preparation ΔEarly-RP and reward-outcome ΔFB-P3 did not vary as a function of Bad-or Good-Performance Feedback. This means that elevated early motor-preparation during reward-anticipation was related to elevated Reward-Evaluation during the FB-P3 time-window, regardless of Performance Evaluation. This relationship is consistent with our previously described null main-effect of Performance-Evaluation on the FB-P3.

As for the ΔLPP, the ΔEarly-RP was only correlated with the ΔBad-Performance, but not ΔGood-Performance, LPP. This suggests that the enhancement of early motor-preparation during reward-anticipation was associated with sustained cognitive-processing (heightened LPP) during reward-outcome, especially when the feedback revealed failure performance. Such pattern is partially consistent with our LPP main effect, given that overall the LPP was enhanced by Bad-Performance (relative to Good-Performance) Feedback.

Contrary to early motor-preparation (i.e., RP), there was no relationship between feedback-anticipation (i.e., SPN) and the FRN reward-outcome ERP. Rather, feedback anticipation was related to later reward-outcome ERPs. Specifically, an increase in the feedback-anticipation ΔSPN following the Reward-Anticipation Cue was associated with an elevated ΔFB-P3 and ΔLPP (but not ΔFRN), regardless of Performance-Evaluation. Because both the FB-P3 and LPP are sensitive to the motivational saliency of feedback (Schupp et al., 2000; Yeung & Sanfey, 2004), we argue that the relationship between feedback-anticipation and reward-outcome ΔERPs were driven by the motivational-salience of the feedback (i.e. reward-evaluation as opposed to performance-evaluation).

Nonetheless, the non-significant correlation between the ΔSPN and ΔFRN contradicts one recent study that reported a relationship between the SPN and Good-Performance FRN (Moris et al., 2013). This discrepancy may reflect methodological differences between our study and that of Moris and colleague (2013). For instance, the interval between the movement and the feedback presentation was 2 s in the current study, but it was only 1 s in the study by Moris and colleague (2013). A long interval (at least 2 s) is essential for isolating the RP from the SPN (Damen & Brunia, 1994). Thus, it is possible that Moris and colleague's SPN was contaminated by the RP, and if so, their finding is consistent with our significant relationship between the ΔRP and ΔFRN. Moreover, Moris and colleague's used an average amplitude of the interval between 250 and 350 ms to define the FRN, while we employed a peak-to-peak method to isolate the FRN from coinciding ERPs, such as the P3 (Holroyd et al., 2003). This suggests that Moris and colleague's FRN may have overlapped with our FRN and FB-P3, and this might help explain the similarity between their observed correlation between the SPN and FRN and our observed correlation between the SPN and P3. Future research should systematically investigate these possibilities.

When considering both early motor-preparation and feedback-anticipation ΔERPs together, we demonstrate, for the first time, that the ΔEarly-RP was associated to both the ΔFRN to Good-Performance feedback and the ΔFB-P3, while the ΔSPN was associated to the ΔLPP. This means that reward-modulation of early motor-preparation (ΔEarly-RP) was uniquely related to how individuals initially evaluated (i.e., less than 450 ms) the feedback in terms of performance-evaluation (ΔFRN) and reward-evaluation (ΔFB-P3). By contrast, reward modulation of feedback-anticipation (ΔSPN) was uniquely related to levels of sustained cognitive-processing (i.e., greater than 450 ms) (ΔLPP) after learning reward-outcome.

Overall, this pattern of relationships between reward-anticipation and reward-outcome ΔERPs may reflect functional-connectivity among reward-network regions, previously demonstrated in fMRI studies (e.g., Camara, Rodriguez-Fornells, & Munte, 2008; Cohen, Heller, & Ranganath, 2005; Di Martino et al., 2008; Menon & Levitin, 2005; Plichta et al., 2013). Specifically, activity in the SMA/Pre-SMA and the anterior insula are thought to underlie the Early-RP (Cunnington et al., 2002; Shibasaki & Hallett, 2006), and the SPN (Kotani et al., 2009), respectively. The SMA/Pre-SMA and the anterior insula, in turn, have been functionally connected with neural regions subserving reward-outcome ERPs (ΔFRN, ΔP3 and ΔLPP), such as the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and basal ganglia (for review see San Martín, 2012; Walsh & Anderson, 2012). The current study extends this line of research by demonstrating the temporal specificity of the reward-network connectivity across specific reward-processing stages (as opposed to connectivity among regions). That is, while fMRI studies provide results regarding where reward-network regions are, our ERP results provide preliminary evidence regarding the connectivity between reward-processing sub-stages.