Abstract

B lymphocytes committed to the production of antibodies binding to antigens on pathogenic bacteria and viruses (natural antibodies) are common components of the normal human B cell repertoire. A major proportion of natural antibodies Is capable of binding multiple antigens (polyreactive antibodies). Using B cells from three HIV-1 seronegative healthy subjects, and purified HIV-1 and β-galactosldase from Escherichia coll as selecting antigen, we generated three natural IgM mAb to HIV-1 and a natural IgM mAb to β-galactosldase. The three HIV-1-selected antibodies (mAb102, mAb103, and mAb 104) were polyreactive. They bound with different affinities (Kd = 10−6 to 10−8 M) to the HIV-1 envelope gp160, the p24 core protein, and the p66 reverse transcriptase, but not to the 120 glycosilated env protein. They also bound to β-galactosidase (Kd ~ 10−7 M), tetanus toxold, and various self antigens. In contrast, the natural mAb selected for binding to β-galactosldase (mAb207.F1) was monoreactive, In that It bound with a high affinity (Kd < 10−8 M) to this antigen, but to none of the other antigens tested, Including HIV-1. Structural analysis of the VH and VL segments revealed that the natural mAb utilized three segments of the VHIV gene family and one of the VHIII family, in conjunction with VL segments of the VλI, VλII, VλIII, or VχIV subgroups. In addition, the natural mAb VH and VL segments were In unmutated or virtually unmutated (germllne) configuration, Including those of the monoreactive mAb207.F1 to β-galactosldase, and were identical or closely related to those utilized by specific autoantibodles or specific antibodies to viral and/or bacterial pathogens. Thus, the present data show that both polyreactive and monoreactive natural antibodies to foreign antigen can be Isolated from the normal human B cell repertoire. They also suggest that the VH and VL segments of not only polyreactive but also monoreactive natural antibodies can be encoded in unmutated or minimally mutated genes, and possibly provide the templates for the specific high affinity antibodies elicited by self or foreign antigens.

Keywords: complimentarity determining region, framework region, Ig VH and VL segments, natural antibodies, polyreactivity

Introduction

The presence in normal animals and humans of a population of circulating molecules reactive with a variety of antigens on viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi, and displaying physicochemical and biological properties similar to those of the antibodies induced by immunization has been recognized for almost a century (reviewed in 1-5). Because they arise independently of known and/or deliberate specific immunization, these Ig have been referred to as ‘natural antibodies’. Natural antibodies also bind to heterotogous plasma and tissue antigens, and include the antibodies responsible for blood group incompatibility and hyperacute rejection of xenografts (1,2,6,7). In fact, their reactivity is not restricted to foreign antigens, but includes a wide spectrum of self antigens, such as hormones, e.g. insulin and thyroglobulin, and cell surface glycoproteins and phospholipids, e.g. surface class II molecules and phosphatidylcholine respectively, or structural cell proteins, e.g. myosin, actin, and tubulin (reviewed in 1-5). mAb with similar antigen-binding properties have been generated by Epstein – Barr virus (EBV)-transformation and/or somatic cell hybridization techniques using B cells from normal humans and mice (reviewed in 3 – 5). Because of their ability to bind microbial antigens and self antigens, natural antibodies may play a major role in the primary line of defense against infections and may contribute, under certain conditions, to the establishment of autoimmune phenomena (reviewed in 3 – 5).

Analysis of natural mAb has shown that these antibodies are in general polyreactive, i.e. a single antibody molecule can bind (with various affinities) multiple antigens, even very different in nature (3–5,8–11). For instance, the natural human mAb we selected for binding to the rabies virus ribonucleoprotein, also bound to ssDNA, human insulin, thyroglobulin, human IgG Fc fragment, bacterial potysaccharides and lipopotysaccharide (LPS) (12). Conversely, natural mAb we selected for binding to ssDNA or insulin also bound to viral and/or bacterial proteins, polysaccharides and LPS (9–11). The polyreactivity of natural antibodies contrasts with the monoreactivity and specificity of ‘antigen-induced’ antibodies (10–14). Whereas monoreactivity and high affinity are ‘acquired’ features of clonotypes and Ig V genes that underwent a process of somatic point-mutation and clonal selection driven by antigen (15–25), polyreactivity is thought to be a function, as we and others have suggested, of unmutated Ig V genes (3–5,16,26–30).

In the present studies, using B cells from healthy subjects and HIV-1 or β-galactosidase from Escherichia coli as selecting antigen, we generated four natural IgM mAb. We found that the three HIV-1 -selected natural mAb were polyreactive while the β-galactosidase-selected mAb was monoreactive and displayed a relatively high affinity for antigen. In addition, we found that not only the polyreactive but also the monoreactive mAb VH and VL segments were encoded in genes in the unmutated or virtually unmutated configuration.

Methods

Generation of human mAb-secreting cell lines

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained from three different healthy (28 – 35 years old) subjects. B lymphocytes were purified, infected with EBV, and cultured in 96-microwell Falcon 3077 plates (Becton-Dickinson, Lincoln Park, NJ) containing irradiated feeder cells (9 – 13,25,29,31,32). After 2 weeks, culture fluids were tested for content of antibodies binding to HIV-1 or E.coli β-galactosidase using specific ELISA (see below). EBV-transformed B cells producing antibodies binding to HIV-1 (mAb102, mAb103, and mAb104) and those producing antibody binding to β-galactosidase (mAb2O7.F1) were selected by sequential subculturing and eventually stabilized by fusion with F3B6 human–mouse hybrid cells (9–13,25,29,31,32). The resulting EBV-transformed B cell hybrids were doned three times and then amplified to produce amounts of mAb suitable for immunochemical analysis.

Analysis of mAb binding to whole HIV-1, HIV-1 components, β-galactosidase, and other antigens

HIV-1 was purified using zonal ultracentrifugation with ribonuclease-free sucrose gradients (33) and heat-inactivated (56°C, 30 min) (MicroGeneSys, Meriden, CT). The HIV-1 gp120 external grycosilated env protein, the gp160 external glycoprotein, the p24 gag polyprotein (derived from a HIV-1 gene fragment which codes for a gag polyprotein that includes all p24 plus 12 amino acids of the C-terminus of p17 and 57 amino acids of the N-terminus of p15), and the p66 reverse transcriptase (derived from an HIV-1 pol gene fragment which codes for all the reverse transcriptase plus 13 amino acids of the C-terminus of protease and 34 amino acids of the N-terminus of the endonuclease) were produced in insect cells using the baculovirus expression system and purified under conditions designed to preserve its biological activity and tertiary structure (MicroGeneSys). β-Galactosidase from E. coli, purified tetanus toxoid, ssDNA, recombinant human insulin, purified thyroglobulin, Fc fragment of human IgG, and BSA were as reported (9–13). HIV-1 and HIV-1 components were used to coat ELISA plates at a protein concentration of 3 – 1 0 μg/ml in 0.05 M carbonate buffer, pH 9.6. The ELISA plate coating conditions for all other antigens were as reported (9–13). Antigen-bound antibodies were detected using affinity-purified horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat antibodies to human IgM (9–13). Competitive inhibition studies involving solid-phase and soluble antigen were performed to calculate the dissociation constant (Kd) values (9–13).

Sequences of the mAb VH and VL genes

Cellular mRNA was isolated from EBV-transformed B cell hybrids using the Fast Track kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). cDNA libraries were constructed from 5 μg of poly(A+) mRNA using the λgt11 phage vector (12,23,24,29). Each cDNA library was screened by filter hybridization using the previously reported VH, CH, Cλ, and Cχ, probes labeled with deoxycytidine 5′-[α-32P]-triphosphate (dCTP) (spec, act., 3000 Ci/mmol, Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) by random priming or γ-32P-end labeled (Cλ oligonucleotJde) (12,23,24,29). After doning of the recombinant phages, the VH and VL gene segments were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the isolated phages using the forward and reverse λgt11 primers. cDNA inserts were digested with EcoRI, purified, and ligated into EcoRI-digested, dephosphorylated pUC18 vector. Recombinant pUC18 plasmids were amplified in DH5α competent E.coli cells and purified (12,23,29). The cloned VH and VL genes were sequenced by the Sanger's dideoxy chain termination method, using the Taq polymerase (12,23–25,29).

Analysis of the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences

DNA sequences were analyzed using the software package of the Genetic Computer Group of the University of Wisconsin, Release 6, and a Model 6000-410 VAX computer (Digital Equipment Corp., Marlboro, MA). Ig VH and VL gene sequence identity searches were performed using the GenBank Database and the FASTA program (34).

Results

Generation and analysis of the human natural mAb

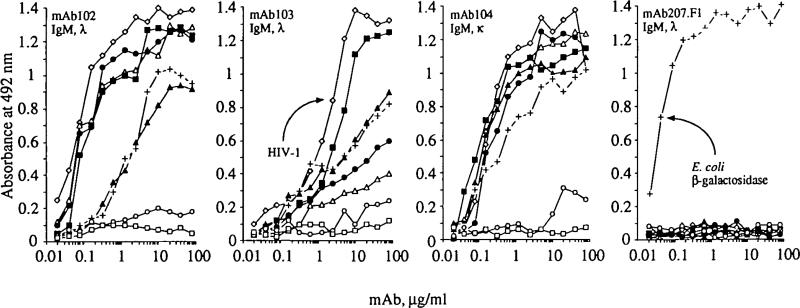

Using B lymphocytes from three different healthy subjects and purified HIV-1 or E. coli β-galactosidase as selecting antigen, we generated three HIV-binding IgM mAb (mAb 102,103, and 104) and one β-galactosidase-binding IgM mAb (mAb207.F1) (Table 1). Three mAb utilized λ and one χL chains. The HIV-1-binding mAb were polyreactive. mAb 102, mAb104, and, at much lower degree, mAb 103 bound with different affinities to different HIV-1 components, including the p66 reverse transcriptase, the p24 gag polyprotein, and the full-length gp160 external env glyco-protein (Table 1). The three mAb bound with very low affinity to the external gp120 env gtycoprotein and failed to neutralize HIV-1 in vitro (data not shown). However, they all bound in a dosesaturable fashion to other foreign antigens, including tetanus toxoid and E. coli β-galactosidase, and self antigens, including human insulin, thyroglobulin, ssDNA, and, much less efficiently, to human IgG Fc fragment (Fig. 1A–C). BothmAb102and 104 bound β-galactosidase with a moderate affinity (Kd = 10−7 M) (Table 1). In contrast to the polyreactivity of the HIV-1-selected mAb, the β-galactosidase-selected mAb207.F1 bound with a high affinity to this antigen (Kd < 10−8 M), but to none of the other antigens tested, including HIV-1 (Fig. 1D and Table 1).

Table 1.

Nucleotide and amino acid differences in VH and VL regions of natural human mAb

| Clone | Donor | mAb chains |

Binding |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 components |

β-galactosidase | ||||||

| H,L | gp160 | gp120 | p66 | p24 | |||

| mAb102 | 267 | μ,λ | ND | >10−4 | 4.7 × 10−7 | >10−4 | 3.0 × 10−7 |

| mAb103 | 267 | μ,λ | ND | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | ND |

| mAb104 | 259 | μ,χ | 1.0 × 10−7 | >10−4 | 1.0 × 10−8 | 6.3 × 10−7 | 2.0 × 10−7 |

| mAb207.F1 | 307 | μ,λ | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | >10−4 | < 10 × 10−8 |

| VH gene |

Df gene | JH gene | VL gene |

JL gene | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Closest segment [family] | Identity (%) | Framework region | Complimentarity determining region | Closest segment [subgroup] | Identity (%) | Framework region | Complimentarity determining region | |||

| 4.33a [VHIV] |

99.0 (99.0) |

3 (1) |

0 (0) |

D21/10 | JH4 | DSC VλIIg [VλII] |

99.3 (98.0) |

0 (0) |

2 (1) |

Jλ1 |

| VH26cb [VHIII] |

1000 (100.00) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

DN2 | JH4 | VλIII.1H [VλIII] |

100.0 (100.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

Jλ2 |

| VH4.21c [VHIV] |

98.7 (99.0) |

3 (1) |

1 (0) |

DXP’1 | JH1 | VχIVj [VχIV] |

97.7 (96.1) |

3 (2) |

4 (2) |

Jχ4 |

| 3d279dd [VHIV] |

99.7 (99.0) |

1 (1) |

(0) (0) |

DK4 | JH2 | T2:C5i [VλI] |

100.0 (100.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

Jλ2 |

Genomic germline VH gene sequences as reported by.

Chen et al (39)

Sanz et al. (37); and

van der Maarel et al. (38). The only nucleotide difference, a G instead of an A in position 213 (resulting in a substitution of an I with an M at position 71 of the deduced amino acid sequence), displayed by the mAb207.F1 sequence when compared with that of the germline 3d279d gene is shared by at least 10 members and/or alleles of the VHIV family, including 4.35 (see Fig. 2).

The expressed D gene sequences displayed only partial identity with those of the reported germline genes (see Results).

Genomic germlme VL gene sequences as reported by. h Cambriato and Kobeck (48)

Klobeck et al. (44). Expressed (possibly unmutated) VL genes as reported by

Paul et al. (46) and

Berinstein et al. (50). The DSC VλII sequence displays 18 nucleotide differences compared with the (only available VλII) genomic germlme VλII 2.1 sequence reported by Brockly et al (47) The mAb207 F1 and T2:C5 Vλ1 gene sequences are identical and displayed only two nucleotide differences with the sequence of the germline Hum1v117 gene (28) (see Fig. 2).

Percentages and number of substitutions in parentheses refer to deduced amino acid sequences.

Fig. 1.

Binding of natural human mAb to HIV-1 (◇), tetanus toxod (■), β-galactosidase from E. coli (+), ssDNA (△), insulin (●), thyroglobulin (▲), Fc fragment of human IgG (○), and BSA (□).

Human natural mAb VH segments

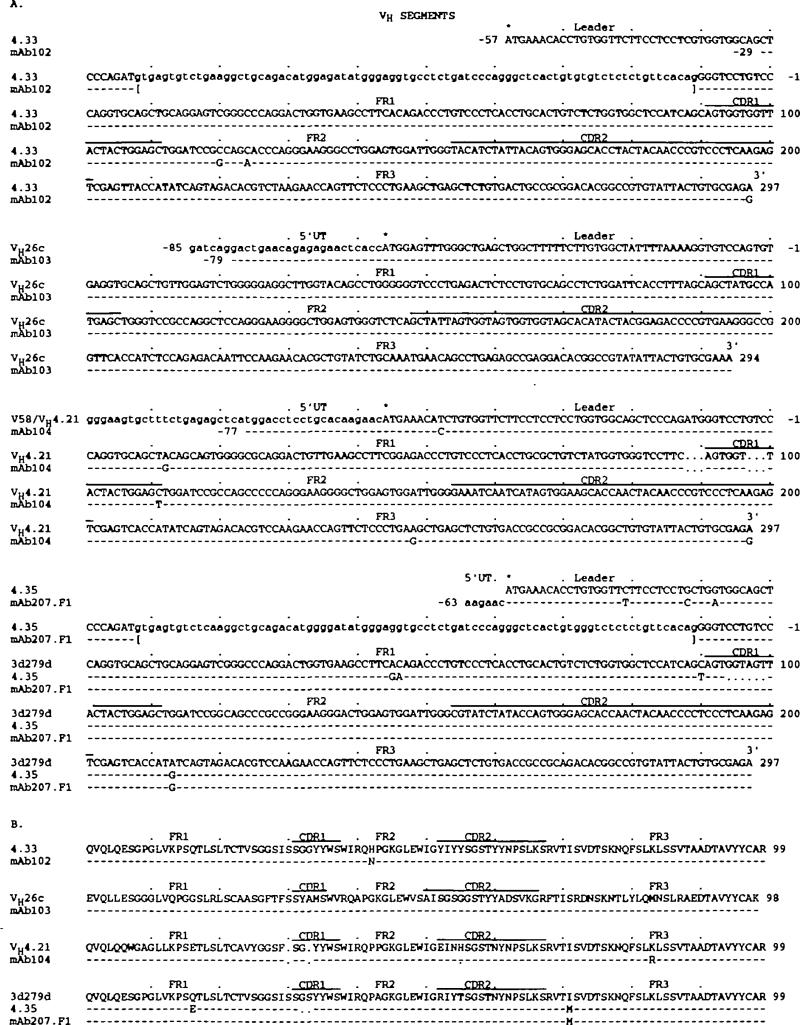

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the VH segments of the four natural mAb are depicted in Fig. 2(A and B respectively). Their differences compared with those of the closest known germline genes are summarized in Table 1. The criterion used for assignment to a given VH gene family was 80% sequence identity. mAb102 VH nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences were virtually identical with those of the 4.33 (35) and related H10 genes (36), members of the VHIV family. Of the three nucleotide differences, only one (in FR2) resulted in a deduced amino acid difference. When compared with that of the germline VH4-21 gene, another member of the VHIV family (37, 38), the mAb104 vH nucleotide sequence displayed only three differences throughout the coding area. These resulted in a single difference in the (FR3) deduced amino acid sequence. Thus, it is conceivable that both mAb102 and mAb104 VH genes represented the expression of minimally polymorphic alleles of the 4.33 VH and VH4-21 genes respectively, although the possibility that they consisted of slightly mutated forms of the above germline genes could not be ruled out. The mAb103 VH gene sequence was identical with that of the germline VH26c gene, a member of the VHIII family (38). Finally, the monoreactive anti-β-galactosidase mAb207.F1 VH gene sequence was identical to that of the germline 3d279d gene, also a member of the VHIV family (39), except for a G instead of an A in position 213, resulting in a substitution of an I with an M at position 71 of the deduced amino acid sequence. Such a unique difference is in fact shared by at least 10 members and/or alleles of the VHIV family, including 4.35 (Fig. 2A and B) (35 – 37,39). This is highly consistent with the hypothesis that the mAb207.F1 VH segment was encoded in a yet unidentified minimally polymorphic allele of the 3d279d gene.

Fig. 2.

Nucteotide (A) and deduced amino acid (B) sequences of the VH genes utilized by the natural human mAb. In each duster, the top sequence is given for comparison and represents the germline VH gene displaying the highest degree of identity to the expressed VH genes of the cluster The 4.33, VH4.2 1 , and 3d279d genes belong to the VHIV family. The leader region sequence of the VH4.21 is not available, that of the V58 gene leader region is provided instead. The VH26c gene is a member of the VHIII family. Dashes indicate identities. Solid lines on the top of each duster depict CDR. Small letters denote untranslated sequences Asterisks indicate translation initiation codons. The present sequences are available form EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession numbers L25291, L25292, L25293, and L25294.

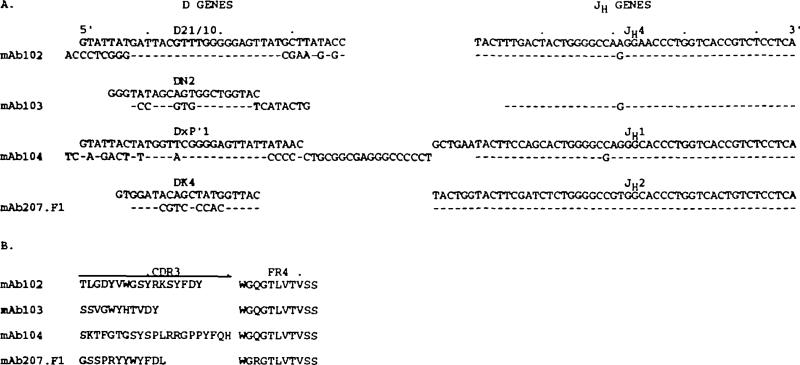

Human natural mAb D and JH genes and configuration of the CDR3

The D segments utilized by the natural mAb were heterogeneous and very different in length (18–51 nucleotides) (Fig. 3A). The mAb102 and mAb104 D segment sequences displayed a high degree of similarity to portions of those of the D21/10 and DxP'1 germline D genes (40,41) respectively. The mAb103 and mAb207.F1 D segment sequences displayed stretches of similarity to those of the germline DN2 (42) and Dk4 (41) genes respectively. All mAb D gene sequences with the exception of that of mAb207.F1 were flanked by unencoded (N) nucleotide additions.

Fig. 3.

Nudeotide (A) and deduced amino acid (B) sequences of the natural mAb D and JH segments. Germline D genes are given for comparison. Dashes indicate identities. The present sequences are available from EMBUGenBank/DDBJ under accession numbers L25291, L25292, L25293, and L25294.

mAb102 and mAb103 utilized intact and truncated forms respectively of the JH4 gene (Fig. 3A). The two expressed JH4 sequences were in germline configuration and displayed an identical nucleotide variation from the germline JH4 gene sequence originally reported by Ravetch et al. (43). This variation has been previously reported in other expressed Ig genes (24,25,29) and is consistent with the prototypic sequence reported by Yamada et al. (44). mAb104 utilized a truncated form of JH1 gene, displaying only one nucleotide difference when compared with the original sequence reported by Ravetch et al. (43). Finally, mAb207.F1 utilized an intact germline JH2 gene.

Figure 3 (B) depicts the deduced amino acid sequences of the joined D – J genes. The first portion of each sequence encodes the CDR3 segment, as defined by Kabat et al. (45). The CDR3-encoding sequence encompasses the whole D gene and the first ‘non-conserved’ portion of the JH gene, up to the invariant W codon (TCG). The remaining ‘conserved’ sequence of the JH gene encodes the FR4. Using these criteria, the expressed CDR3 varied in length from 11 (mAb103) to 23 (mAb104) amino acids. The expressed FR4 sequences were conserved and invariable in length.

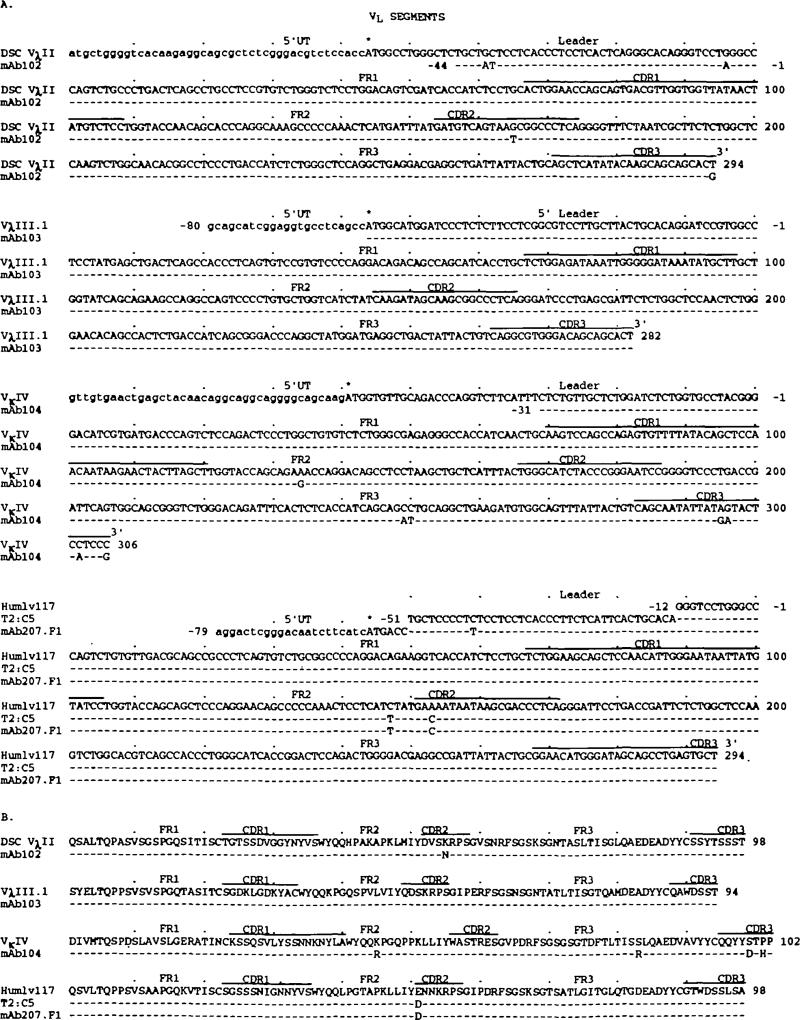

Human natural mAb VL – JL segments

The nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the VL segments of the four natural mAb are depicted in Fig. 4(A and B respectively). Their drfferences when compared with the closest known germline genomic or expressed gene sequences are summarized in Table 1. The mAb102 Vλ nudeotide and deduced amino acid sequences were virtually identical with those of the expressed DSC VλII (VλII subgroup) gene (46), which differs by 18 nudeotide from the only genomic germline VλII gene sequenced, VλII 2.1 (47). The mAb103 Vλ gene sequence was identical with that of the germline VλII.1 gene (VλIII subgroup) (48). The mAb104 Vχ nudeotide and deduced amino acid sequences displayed the highest degrees of identity with those of the germline Vχ4 gene (49). Finally, the mAb207.F1 Vλ gene sequence was identical with that of the expressed and T2:C5 gene (VλI subgroup) (50). The two identical sequences differed by only two nucleotides from that of the germline Hum1v117 Vλ1 gene (28) and likely constituted the expression of a polymorphic allele or a Hum1v117-like gene.

Fig. 4.

Nucleotide (A) and deduced amino add (B) sequences of the VL genes utilized by the natural human mAb. In each duster, the top sequence is given for comparison and represents the published VL gene displaying the highest degree of homotogy to the expressed VL genes of the cluster. VλIII.1 (VλIII subgroup), VλIV, and Hum1v117 (VλI subgroup) are sequences of genomic germline genes. T2:C5 (VλI subgroup) and DSC VλII are sequences rearranged, but possibly unmutated genes. Dashes ridicate identities. Solid lines on the top of each duster depict complimentarily determining regions. Small letters denote untranslated sequences. Asterisks indicate translation initiation codons. The present sequences are available from EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ under accession numbers L25295, L25296, L25297, and L25298.

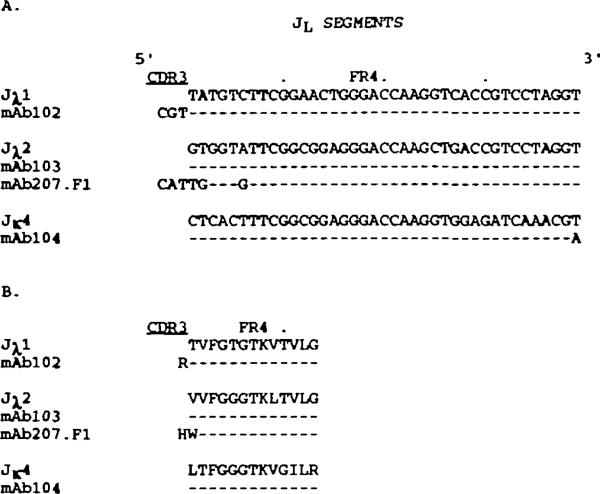

The nudeotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the JL segments of the four natural mAb are depicted in Fig. 5(A and B respectively). The mAb102 utilized an intact and unmutated Jλ1 gene. The mAb103 and mAb207.F1 utilized untruncated forms of the Jλ2 gene incomplete and virtually complete germline configuration respectively. Finally, the mAb104 utilized an untruncated Jχ4 gene with one silent change. Both mAb102 and mAb207.F1 Jλ gene sequences were 5’ flanked by three nucleotides, unencoded in the respective Vλ genes and likely representing N additions. Such unencoded additions might also account for the first two nucleotides of the mAb207.Fi Jλ2 gene sequence.

Fig. 5.

Nucleobde (A) and deduced amino acid (B) sequences of the JL segments of the natural mAb. In each cluster, the top sequence is given for comparison and represents the published germline JL gene displaying the highest degree of homology to the expressed JL genes of the cluster. Dashes indicate identities. The present sequences are available from EMBUGenBank/DDBJ under accession numbers L25295, L25296, L25297, and L25298.

Overall configuration of the natural mAb VH and VL segments

The above structural analysis showed that the mAb 103 VH and Vλ segment sequences were identical with the deduced amino acid sequences of the germline VH26c and VλIII genes respectively; and that the mAb207.F1 VH and Vλ segment sequences were identical with the deduced amino acid sequence of a putative minimally polymorphic allele of the germline 3d279 gene and that of the putative T2:C4 variant of the Hum1v117 VλI gene respectively. The mAb102 VH and Vλ segment sequences displayed each only one difference compared with the deduced amino acid sequences of the germline 4.33 and DSC VλII genes respectively, suggesting that they represented the expression of minimally polymorphic and/or mutated germline genes. The mAb104 VH sequence displayed only one difference (in FR3) compared with the deduced amino acid sequence of the germline VH4-21 gene, while the Vχ segment sequence displayed four differences compared with the deduced amino acid sequence of the germline VχIV gene. The well documented polymorphism of the VHIV family genes (35–37,39,51), the unmutated configuration of the VH and Vχ FR4 sequences, and the fact that the R and D amino add variations found at position 83 and 99 respedively of the mAb104 VχIV segment are displayed by other expressed VχIV segments (45) are consistent with the hypothesis that the mAb104 V segments constituted unmutated forms of VH4-21 and VχIV polymorphic alleles. Alternatively, the mAb104 V segments could represent the expression of VH4-21 and VχIV genes that accumulated two to three somatic point-mutations. Such putative somatic point-mutations, however, did not display a nature and a distribution characteristic of those resulting from an antigen-dependent selection process.

Discussion

We analyzed the VH and VL segment structure and reactivity of three natural IgM mAb we generated by selection for binding to HIV-1, a foreign viral mosaic antigen, and those of a natural IgM mAb we generated by selection for binding to β-galactosidase from E. coli, a foreign bacterial antigen, using B cells from three healthy HIV-1 negative subjects. We found that: (i) consistent with the polyreactive nature of a major proportion of natural antibodies was the reactivity with multiple foreign and self antigen displayed by the three HIV-1-selected mAb; (ii) in spite of the β-galactosidase-binding activity displayed by a large proportion of natural polyreactive antibodies (4,11), including mAb102, mAb103, and mAb104, selection for binding to β-galactosidase led to the generation of the ‘specific’ IgM mAb207.F1; and, finally, (iii) not only the three polyreactive mAb, but also the monoreactive mAb207.F1 displayed unmutated or virtually unmutated VH and V L segments.

This is one of the first reports providing the complete structure of the VH and VL segments of human polyreactive and mono-reactive natural antibodies selected for binding to biologically relevant foreign (viral and bacterial) antigens, and showing that these V segments are unmutated or virtually unmutated. The putatively unmutated configuration of the V segments of the three polyreactive natural IgM is consistent with: (i) the germline configuration of both VH and VL chains of another human polyreactive natural IgM mAb, Kim 4.6, with well characterized antigen-binding activity (52). This mAb was generated in a healthy subject by selection for binding to ssDNA, and also reacts with cardiolipin, synthetic polynucleotides, and RNA, and utilizes a germline VHIII gene, 1.9111, in conjunction with a germline Vλ I gene, designated Hum1v117(28); and (ii) the nearly unmutated configuration of the VH and VL segments of two natural polyreactive mAb binding xenoantigen, self antigen, and chemical haptens, generated from spleen cells of a normal, non-immune BALB/c mouse (26). Thus, utilization of germline genes is associated with potyreactivity of the encoded Ig VH and VL segments in both human and murine natural antibodies. Application of antjgenic pressure to polyreactive natural antibody-producing cell precursors may lead through somatic hypermutation and sequential selection to affinity maturation (3–5).

For instance, in A/J mice, sequential selection by p-azophenyl arsonate of polyreactive natural antibody-producing cells displaying the dominant VH-ldCR (or CRI-A) idiotype results eventually in the generation of high affinity anti-arsonate IgG (16). Early stages of a similar antigen driven selection process may underlie the high proportion of somatically mutated IgM-producing cell precursors found in the human peripheral blood (53–55). Somatic hypermutation and antigen-driven clonal selection of polyreactive antibody-producing cell precursors can lead to an increased antibody affinity for the selecting antigen, but not necessarily to loss of polyreactivity, as suggested by our recent demonstration of antigen-selected point-mutations in polyreactive human IgG mAb (56). As shown in one of the present natural antibodies (mAb207.F1), monoreactivity and relatively high affinity for an exogerious antigen can be encoded in unmutated VH and VL segments. This contention is further supported by the unmutated configuration of the VH and VL segments of the monoreactive mAb to self antigen, particularly DNA, we recently generated in healthy subjects (11 and Chai et al., in preparation). The unmutated or minimally mutated configuration of the present not only polyreactive but also monoreactive mAb VH and VL segments would be consistent with the definition, proposed here, of natural antibodies as Ig binding to foreign antigens, including those on bacteria and viruses, and/or self antigen and produced by clones emerging in an antigen-independent fashion.

Findings in humans and mice have suggested that the antigen-binding properties of individual polyreactive antibodies are distinctive (reviewed in 3 – 5). Accordingly, the present three polyreactive IgM mAb display discrete antigen-binding activities for different self and foreign antigens. The functional ‘uniqueness’ of each IgM likely reflects the structural heterogeneity of the antigen-binding sites of these mAb, which display different assortments of VH, D, and JH segments, as well as VL and JL segments, and different junctional VH – D – JH and VL – JL sequences. Although some unmutated V segments display an inherent affinity for certain antigens in mice, e.g. VHOx1 for 2-phenyl-5-oxazolone (18), S107 VH1 for phosphorylcholine (19), VH11 and VH12 for phosphatidylcholine (reviewed in 57), and S107 VH11 for DNA (58), or in humans, e.g. VH4-21 and VχIIb for the red cell i/l antigen and IgG Fc fragment respectively (59–61), the somatically generated H chain CDR3 appears to be the major contributor to the overall function of the antigen-binding site, at least in the case of relatively large proteinic antigens (62,63). The primary structures of the three polyreactive IgM mAb H chain CDR3 were highly divergent in composition and length, and did not allow for the identification of obvious common motifs possibly responsible for polyreactivity. Thus, if, consistent with what has been suggested by the in vitro expression of human IgM rheumatoid factor (RF) H and L chain genes (64), and by a census of 84 natural polyreactive and antigen-induced monoreactive murine mAb (65), the H chain CDR3 provides the correlate for polyreactivity, it does so by virtue of a discrete primary structure in each of the polyreactive mAb reported here.

The present findings further substantiate the hypothesis that the spectra of natural reactivities with foreign and self antigens vastly overlap as a result of the polyreactivity of a major proportion of the natural antibody clonotypes. They also further suggest that natural antibodies provide the templates for the generation of disease-related autoantibodies as well as specific high affinity antibodies induced by foreign antigens, particularly viruses and bacteria (reviewed in 66–70). For instance, while a completely unmutated copy of the VH26c gene, utilized by the mAb103 and the polyreactive naturaJ IgM mAb18 we reported elsewhere (27), was originally identified as encoding the VH segment of an anti-DNA autoantibody from a SLE patient (71), mutated copies of the VH26c gene are utilized by other anti-DNA (21,88) and RF (22,72,73) IgG and IgM autoantibodies from with SLE and rheumatoid arthritis patients respectively. In the case of foreign antigens, mutated VH26c segments are utilized by high affinity specific antibodies to pathogenic viruses, including IgG mAb elicited through affinity maturation in healthy subjects by rabies virus (12,24) or herpes simplex virus (74), and by specific antibodies to pathogenic bacteria, including IgG and IgM mAb induced in healthy subjects by Haemophilus influenzas type b polysaccharide (75). Analogously, unmutated and mutated forms of the VH4-21 gene are utilized by a variety of RF autoantibodies generated in healthy subjects, rheumatoid patients, as well as patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (reviewed in 67 – 69). Also, mostly unmutated copies of the VH4-21 gene are utilized by the vast majority of anti-i and anti-l red blood cell IgM auto-antibodies (cold agglutinins) generated in patients with idiopathic cold agglutinin disease (CAD) or CAD associated with B cell lymphomas (59,60). A gene consisting of a somatically mutated form of 4.33, utilized by the polyreactive anti-HIV-1 natural mAb102 or closely related to 4.33, encodes the VH segment of the high affinity lgG2 mAb 12-116 (74), which is specific for a segment of the HIV-1 gp41 mapping amino acids 644 – 663 (V3 loop), and was generated using B cells from a HIV-1 seropositive subject. Finally somatically mutated forms of the V71-2 (VHIV) segment, a gene highly related to 3d279d (38,51), utilized by the mAb207.F1, are utilized by some RF and other autoantibodies (reviewed in 66–70).

Despite the smaller number of reported VH gene sequences compared with that of VH gene sequences, it was possible to establish that VH segments identical or similar to those utilized by the present four natural mAb are utilized also by different RF and/or anti-DNA autoantibodies derived from autoimmune patients, as well as by specific high affinity antibodies to microbial pathogens. For instance, a virtually identical copy of the VλII gene, utilized by mAb102, is utilized by an anti-DNA IgM auto-antibody bearing the characteristic 18.2 idiotype (46), and minimal variants of the mAb102 VλII gene as well as other VλII genes are utilized by specific IgG and IgA antibodies elicited by H. influenzae type b polysaccharide (77). Segments consisting of genes related to or, more likely, mutated copies of the VλIII and VλI genes utilized by mAb103 and mAb207.F1 respectively, are utilized by different IgM, IgG, and IgA RF (22,25,29,72). Finally, mutated copies of the single VχIV gene (mAb104) are utilized by an IgA RF (78) and an anti-DNA IgG autoantibody (21), as well as by specific IgM mAb to Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A (79) and to Streptococcus group A carbohydrate N-acetylgucosammine (80,81).

Although limited in number, the assortment of the VH genes utilized by the present natural antibodies is consistent with the hypothesis postulated by Walter et al. (82) and van Djik et al. (83), on the basis of DNA deletional mapping in a large panel of EBV-transformed B cells, that the elements located within 800–1000 kb 5’ of the JH locus account for the majority of the ‘functional’ human VH genes. Two of the natural mAb VHIV genes, VH4-21 and 3d279d, have been mapped to <650 and 850 kb respectively of the JH locus (38,73). The third natural mAb VHIV gene, 4.33, has not been located by the most recent analyses of the chromosome 14 long arm 14q32.3 region, but what it is likely an allelic form of it, the 4.34 gene, has been mapped to <500 kb 5’ of the JH locus (38). Finally, the fourth natural mAb VH gene, VH26c, has been mapped to ~350 kb 5’ of the JH locus (84). The high frequency of expression in the normal and autoimmune B cell repertoires of at least two of these ‘JH-proximal’ VH genes, i.e. VH4.21 and VH26c, has been documented (66–69, 85–87). If confirmed, the notion that a significant fraction of the expressed human Ig VH gene repertoire arises from a preimmune repertoire that is dominated by relatively few VH genes would suggest a significant evolutionary advantage for the expression of polyreactive B clonotypes which are encoded in germlme Ig V genes. A limited number of polyreactive (natural) clonotypes could provide the precursors form which a diverse repertoire arises by clonal selection.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by US Public Health Service grants AR-40908 and CA-16087 (15S1). This is publication no. 21 from the Jeanette Greenspan Laboratory for Cancer Research.

Abbreviations

- CAD

cold agglutinin disease

- EBV

Epstein – Barr virus

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RF

rheumatoid factor

References

- 1.Boyden S. Natural antibodies and the immune response. Adv. Immunol. 1964;5:1. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60271-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michael JG. NaturaJ antibodies Curr. Top. Microbhl. Immunol. 1969;48:43. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-46163-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avrameas S. Natural autoantibodies: from 'horror autotoxicus' to 'gnothi seuton'. Immunol. Today. 1991;12:154. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(05)80045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riboldi P, Kasaian MT, Mantovani L, Ikematsu H, Casali P. Natural antibodies. In: Bona CA, Siminovitch K, Zanetti M, Theofilopoulos AN, editors. The Molecular Pathology of Auto-immune diseases. Gordon and Breach; Philadelphia: 1993. p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casali P. Immunoglobulin M. In: Roitt IM, Delves PJ, editors. Encyclopaedia of Immunology. II. Academic Press; London: 1992. p. 743. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turman MA, Casali P, Notkins AL, Bach FH, Platt JS. Polyreactive antibodies from CD5+ B cells: antigen specificity and relationship to xenoreactve natural antibodies. Transplantation. 1991;52:710. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199110000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geller RL, Bach FH, Turman MA, Casali P, Platt JS. Polyreactive natural antibodies are deposited in rejected discordant xenografts. Transplantation. 1993;55:168. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199301000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casali P, Kasaian MT, Haughton G. B-1 (CD5 B) cells. In: Coutinho A, Kazatchkine MD, editors. Autoimmunity. John Wiley; New York: 1993. p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura M, Burastero SE, Notkins AL, Casali P. Human monoclonal rheumatoid factor-like antibodies from CD5 (Leu-1)+ B cells are polyreactive. J. Immunol. 1988;140:4180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura M, Burastero SE, Ueki Y, Larrick JW, Notkins AL, Casali P. Probing the normal and autoimmune B cell repertoire with EBV. Frequency of B cells producing monoreactive high affinity autoantibodies in patients with Hashimoto's disease and SLE. J. Immunol. 1989;141:4165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasaian MT, Ikematsu H, Casali P. Identification and analysis of a novel human CD5− B lymphocyte subset producing natural antibodies. J Immunol. 1992;148:2690. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueki Y, Goldfarb IS, Harindranath N, Gore M, Koprowski H, Notkins AL, Casali P. Clonal analysis of a human antibody response. Quantitation of antibody-producing cell precursors and generation of monoclonal IgM, IgG, and IgA to rabies virus. J. Exp. Med. 1990;171:19. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casali P, Burastero SE, Nakamura M, Inghirami G, Notkins AL. Human lymphocytes making rheumatoid factor and antibody to ssDNA belong to Leu-1+ B-cell subset. Science. 1987;236:77. doi: 10.1126/science.3105056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams RC, Jr, Malone CC, Casali P. Heteroclitic polyclonal and monoclonal anti-Gm (a) and anti-Gm (g) rheumatoid factors react with eprtopes induced in Gm (a-), Gm (g-) IgG by interaction with antigen or by non-specific aggregation. A possible mechanism for the in vivo generation of rheumatoid factors. J. Immunol. 1992;149:1817. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKean D, Huppi K, Bell M, Staudt L, Gerhard W, Weigert MG. Gmeneration of antibody diversity in the immune response of Balb/c mice to influenza virus hemagglutinin. Proc. NatlAcad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:3180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.10.3180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naparstek Y, Andre-Schwartz J, Manser T, Wysocki LJ, Brettman L, Stollar D, Gefter M, Schwartz RS. A single germline VH gene segment of normal A/J mice encodes auto-antibodies characteristic of systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Exp. Med. 1986;164:614. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.2.614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shlomchik MJ, Marshak-Rothstem A, Wolfowicz CB, Rothstein TL, Weigert MG. The role of clonal selection and somatic mutation in autoimmunity Nature. 1987;328:805. doi: 10.1038/328805a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berek C, Mitetein C. Mutation drift and repertoire shift in the maturation of the immune response. Immunol. Rev. 96.23. 1987 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1987.tb00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy NS, Malipiero UV, Lebecque SG, Gearhart PJ. Early onset of somatic mutation in immunoglobulin VH genes during the primary immune response. J. Exp Med. 1989;169:2007. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.6.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shlomchik M, Mascelli M, Shan H, Radic MZ, Pisetsky D, Marshak-Rothstein A, Weigert MG. Anti-DNA antibodies from autoimmune mice arise by clonal expansion and somatic mutation. J. Exp. Med. 1990;171:265. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manheimer-Lory A, Katz JB, Pillinger M, Ghossein C, Smith A, Diamond B. Molecular characteristics of antibodies bearing an anti-DNA-associated idiotype. J. Exp. Med. 1991;174:1639. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olee T, Liu EW, Huang D-F, Soto-Gil RW, Deftos M, Kozin F, Carson DA, Chen PP. Genetic analysis of self-associating immunoglobulin G rheumatoid factors from two rheumatoid synovia implicates an antigen driven response. J. Exp. Med. 1992;172:831. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.3.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikematsu H, Harindranath N, Casali P. Somatic mutations in the VH genes of high affinity antibodies to self and foreign antigens produced by human CD5+ and CD5− B cells. Ann. NYAcad. Sci. 1992;651:319. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb24631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikematsu H, Harindranath N, Ueki Y, Notkins AL, Casali P. Clonal analysis of a human antibody response. II. Sequences of the VH genes of human monoclonal IgM, IgG and IgA to rabies virus reveal preferential utilization of the VHIII segments and somatic hypermutation. J. Immunol. 1993;150:1325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mantovani L, Wilder RL, Casali P. Human rheumatoid B-1a (CD5+ B) cells make high affinity somaticaHy hypermutated IgM rheumatoid factors. J. Immunol. 1993;151:473. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baccala R, Quang TV, Gilbert M, Ternynck T, Avrameas S. Two murine natural polyreactive autoantibodies are encoded by nonmutated germ-line genes. Proc. NatlAcad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:4624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanz I, Casali P, Thomas JW, Notkins AL, Capra JD. Nucleotide sequences of eight human natural autoantibodies VH region reveals apparent restricted use of VH families. J. Immunol. 1989;142:4054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sminovitch K,A, Misener V, Kwong PC, Song Q-L, Chen PP. A natural autoantibody is encoded by germline heavy and lambda light chain variable region genes without somatic mutation. J. Clin. Invest. 1989;84:1675. doi: 10.1172/JCI114347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harindranath N, Goidfarb IS, Ikematsu H, Burastero SE, Wilder RL, Notkins AL, Casali P. Complete sequences of the genes encoding the VH and VL regions of low and high affinity monoclonal IgM and IgA1 rheumatoid factors produced by CD5+ B cells from a rheumatoid arthritis patient. Int. Immunol. 1991;3:865. doi: 10.1093/intimm/3.9.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardy RR. Variable gene usage, physiology and development of LY-1+ (CD5+) B cells. Cur. Opin. Immunol. 1992;4:181. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(92)90010-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larrick JW, Chiang YL, Shen-Dong R, Senyk G, Casali P. Generation of specific monoclonal antibodies by in vitro expansion of B cells. A novel recombinant DNA approach. In: Borrebaek CAK, editor. In Vitro Immunization of Hybndoma Technology. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1988. p. 231. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura M, Casali P. Generation of human monoclonal antibody-producing cell lines by Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-transformation and somatic cell hybridization techniques. Application to the analysis of the autoimmune B cell repertoire. Immunomethods. 1992;1:159. doi: 10.1016/S1058-6687(05)80012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toplin I, Sottong P. Large-volume purification of tumor viruses by use of zonal centrifugation. Appl. Microbiol. 1972;23:1010. doi: 10.1128/am.23.5.1010-1014.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parson WR. Rapid and sensitive sequence comparison with FASTP and FASTA. Methods Enzymol. 1990;183:63. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)83007-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weng N, Snyder JG, Yu-Lee L, Marcus DM. Polymorphism of human immunoglobulin VH4 germ-line genes. Eur. J. Immunol. 1992;22:1075. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Es JH, Heutinmk M, Aanstoot H, Logtenberg T. Sequence analysis of members of the human Ig VH4 gene family derived from a single VH locus. J. Immunol. 1992;149:492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanz I, Kelly P, Williams C, Schdl S, Tucker P, Capra JD. The smaller human VH gene families display remarkably little polymorphism. EMBO J. 1989;8:3741. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Maarel S, van Dijk KW, Alexander CM, Sasso EH, Bull A, Milner EC. Chromosomal organization of the human VH4 gene family. J. Immunol. 1993;150:2858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen PP, Liu M-F, Sinha S, Carson DA. A 16/6 idiotype-positrve anti-DNA antibody is encoded by a conserved VH gene with no somatic mutation. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:1429. doi: 10.1002/art.1780311113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buluwela L, Albertson DG, Sherrington P, Rabbitts PH, Spurr N, Rabbitts TH. The use of chromosomal translocations to study human immunoglobulin gene organization, mapping DH segments with 35 kb of the Cμ gene and identification of a new DH locus. EMBO J. 1988;7:2003. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03039.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ichihara Y, Matsuoka H, Kurosawa Y. Organization of human immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity gene loci. EMBO J. 1988;7:4141. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mortari F, Newton JA, Wang JY, Schroeder HW. The human cord blood antibody repertoire. Frequent usage of the V H7 gene family. Eur. J. Immunol. 1992;22:241. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ravetch JV, Siebenlist U, Korsmeyer S, Waldmann T, Leder P. Structure of the human immunoglobulin μ locus: characterization of embryonic and rearranged J and D genes. Cell. 1981;27:583. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90400-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamada M, Wasserman R, Reichard BA, Shane S, Caton AJ, Rovera G. Preferential utilization of specific immunoglobulin heavy chain diversity and joining segments in adult human peripheral blood B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:395. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kabat EA, Wu TT, Perry HM, Gottesman KS, Foeller C. Sequences of Proteins of Immunological Interest. 5th edn. US Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC.: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paul E, Livneh A, Manheimer-Lory AJ, Diamond B. Characterization of the human Ig Vxll gene family and analysis of VλII and Cλ polymorphism in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 1991;147:2771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brockly F, Alexender D, Chuchuna P, Huck S, Lefranc G, Lefranc M-P. First nucleotide sequence of a human immunoglobulin variable λ gene belonging to subgroup II. Nucleic Adds Res. 1989;17:3976. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.10.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cambriato G, Klobeck H-G. Vλ and Jλ - Cλ gene segments of the human immunoglobulin λ light chain locus are separated by 14 kb and rearrange by a deletion mechanism. Eur. J. Immunol. 1991;21:1513. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klobeck H-G, Bornkamm GW, Combriato G, Mocikat R, Pohlenz H-O, Zachau HG. Subgroup IV of human immungtobulin χ light chain is encoded by a single germline gene. Nucleic Adds Res. 1985;13:6515. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.18.6515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berinstein N, Levy S, Levy R. Activation of an excluded immunoglobulin allete in human B lymphoma cell line. Science. 1989;244:337. doi: 10.1126/science.2496466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee KH, Matsuda F, Kinashi T, Kodaira M, Honjo T. A novel family of variable region genes of the human immunoglobulin heavy chain. J. Mol. Bhl. 1987;195:761. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90482-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cairns E, Kwong PC, Misener V, Ip P, Bell DA, Sirrrinovitch K. Analysis of the variable region genes encoding a human anti-DNA autoantibody of normal origin. Implications for the molecular basis of human autoimmune responses. J. Immunol. 1989;143:685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Es JH, Gmelig Meyling FHJ, Logtenberg T. High frequency of somatically mutated IgM molecules in the human adult blood B cell repertoire. Eur. J. Immunol. 1992;22:2761. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang C, Stewart AK, Schwartz RS, Stollar BD. Immunoglobulin heavy chain gene expression in peripheral blood lymphocytes. J. Clin. Invest. 89.1331. 1992 doi: 10.1172/JCI115719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cai J, Humphries C, Lutz C, Tucker PW. Analysis of VH251 gene mutation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and normal B cell subsets. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1992;651:384. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb24639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ikematsu H, Kasaian MT, Schettino EW, Casali P. Structural analysts of the VH - D - JH segments of human poly-reactive IgG mAb evidence for somatic selection J. Immunol. 1993;151:3604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arnold LW, Haughton G. Autoantibodies to phosphatidylcholine. The munne antibromelain RBC response. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1992;651:354. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb24635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shefner R, Kleiner G, Turken A, Papazian L, Diamond B. A novel class of anti-DNA antibodies identified in Balb/c mice. J Exp Med. 1991;173:287. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.2.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pasucal V, Victor K, Spellerberg M, Hamblin TJ, Stevenson FK, Capra JD. VH restriction among human cold agglutinins. The VH4-21 gene segment is required to encode anti-I and anti-I specificities. J. Immunol. 1992;149:2337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Silberstein LE, Jeffereis LC, Goldman J, Moore JS, Nowell PC, Roelcke D, Pruzanski W, Roudier J, Silverman GJ. Variable region gene analysis of pathologic human auto-antibodies to the related i and I red blood cell antigens. Stood. 1991;78:2372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hay FC, Soltys AJ, Tribbik G, Geyem HM. Framewark peptides from χIIIb rheumatoid factor light chains with binding activity for aggregated IgG. Eur. J. Immunol. 1991;21:1837. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Amit AG, Mariuzza RA, Phillips SE, Poliak RJ. Three-dimensional structure of an antigen-antibody complex at 2.8 A resolution. Science. 1986;233:747. doi: 10.1126/science.2426778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stanfield RL, Reser TM, Lerner RA, Wilson IA. Crystal structure of an antibody to a peptide and its complex with peptide antigen at 2.8 Å. Science. 1990;248:712. doi: 10.1126/science.2333521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martin T, Duffy SF, Carson DA, Kipps TJ. Evidence for somatic selection of natural antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 1992:175–983. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen C, Stenzel-Poore MP, Rittenberg MB. Natural and polyreactive antibodies differing from antigen-induced antibodies in the H chain CDR3. J. Immunol. 1991;147:2359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dersimonian H, Long A, Rubinstein D, Stoflar DB, Schwartz RS. VH genes of human autoantibodies. Int. Rev. Immunol. 1990;5:253. doi: 10.3109/08830189009056733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pascual V, Capra JD. Human immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region genes: organization, polymorphism, and expression. Adv. Immunol. 1991;49:1. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60774-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pascual V, Capra JD. VH4-21, a human gene segment overrepresented in the autoimmune repertoire. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:11. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pascual V, Victor K, Randen I, Thompson K, Natvig JB, Capra JD. IgM rheumatoid factors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis derive from a diverse array of germline immunoglobulin genes and display little somatic variation. J. Rheumathol. 1992;19(Suppl.):50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stewart AK, Huang C, Stollar DB, Schwartz RS. VH gene representation in autoantibodies reflects the normal human B cell repertoire. Immunol Rev. 1992;128:101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1992.tb00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dersimonian H, Schwartz RS, Barrett KJ, Stollar DB. Relationship of human variable region heavy chain germ-line genes to genes encoding anti-DNA autoantibodies. J. Immunol. 1987;139:2496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pascual V, Victor K, Randen I, Thomson K, Steinitz M, Forre O, Fu S-M, Natvig JB, Capra JD. Nucleotide sequence analysis of rheumatoid factors and polyreactive antibodies derived from patients with rheumatoid arthritis reveals diverse use of VH and VL gene segments and extensive variability in CDR3. Scand. J. Immunol. 1992;36:349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1992.tb03108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pascual V, Randen I, Thompson K, Sioud M, Forre O, Natvig J, Capra JD. The complete nucleotide sequences of the heavy chain variable regions of six monospecific rheumatoid factors derived from EBV-transformed B cells isolated from the synovial tissue of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Further evidence that some autoantibodies are unmutated copies of germline genes. J. CUn. Invest. 1990;86:1320. doi: 10.1172/JCI114841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huang D-F, Olee T, Masuhiko Y, Matsumoto Y, Carson DA, Chen PP. Sequence analyses of three immunoglobulin G ant-virus antibodies reveal their utilization of autoantibody-related immunoglobulin VH genes, but not Vx genes. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;90:2197. doi: 10.1172/JCI116105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adderson EE, Shackelford PG, Quinn A, Caroll WL. Restricted Ig H chain V gene usage in the human antibody response to Haemophilis influenzae type b capsular polysaccharide. J. Immunol. 1991;147:667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Andris JS, Johnson S, Zolla-Paztner S, Capra JD. Molecular characterization of five human anti-human immuno-deficiency virus type 1 antibody heavy chains reveals extensive somatic mutation typical of an antigen-driven immune response. Proc. Natl Acad Sci. USA. 1991;88:7783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Adderson EE, Shackelford PG, Insel RA, Quinn A, Wilson PM, Caroll WL. Immunoglobulin light chain variable region gene sequences for human antibodies to Haemophilus influenzae type b capsular potysaccharide are dominated by a limited number of Vx and Vx segments and VJ combinations. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;89:729. doi: 10.1172/JCI115649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gause A, Kuppers R, Mierau R. A somatically mutated VχIV gene encoding a human rheumatoid factor light chain Clin. Exp Immunol. 1992;88:430. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06467.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nakatani TN, Nomura K, Origome H, Ohtsuka H, Noguchi H. Functional expression of human monoclonal antibody genes directed against Pseudomonas exotoxin A in mouse myeloma cells. Bio/Technology. 1989;7:805. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Marsh P, Mills F, Gould H. Detection of a unique VχIV gene by a cloned cDNA probe. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:6531. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.18.6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Steinitz M, Seppala I, Eichman K, Klein G. Establishment of a human lymphoblastoma cell line with specific antibody production against group A Streptococcal carbohydrate. Immunobiotogy. 1979;156:41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Walter MA, Dosch HM, Cox DW. Adeletional map of the human immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region. J. Exp. Med. 1991;174:335. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.2.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van Djik KW, Milner LA, Milner ECB. Mapping of human H chain V region genes (VH) using detetonal analysts and pulsed field gel electrophoresis. J. Immunol. 1992;148:2923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Matsuda F, Shin EK, Nagaoka H, Matsumura R, Hamo M, FukHa Y, Takaishi S, Imai T, Riley JH, Anand R, Soeda E, Honjo T. Structure and physical map of 64 variable segments in the 3′ 0.8-megabase region of the human immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus. Nature Genetics. 1993;3:88. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schroeder HW, Hillson JL, Perlmutter RM. Earty restriction of the human antibody repertoire. Science. 1987;238:791. doi: 10.1126/science.3118465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schroeder HW, Jr, Wang JY. Preferential utilization of conserved immunoglobulin heavy chain variable gene segments during human fetal life. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:6146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stewart AK, Huang C, Stollar BD, Schwartz RS. High frequency representation of a single VH gene in the expressed human B cell repertoire. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:409. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.2.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kasaian MT, Ikematsu H, Balow JE, Casali P. VH and VL segment structure of monoreactive and polyreactive anti-DNA IgA autoantibodies in patients with SLE. J. Immunol. 1994 in press. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]