Abstract

Background/Aims

We attempted to investigate the prognosis of signet-ring cell carcinoma (SRC) patients who underwent curative surgery by comparing them with age-, sex-, and stage-matched non-mucinous adenocarcinoma (NMAC) patients.

Methods

Between January 2003 and December 2011, 19 patients with primary SRC of the colorectum underwent curative surgery. Four SRC patients under the age of 40 were excluded, and the clinicopathological data of 15 patients (7 men; median age, 56 years) were reviewed and compared with the data of 75 NMAC patients matched by age, sex, and pathologic stage.

Results

The median follow-up duration was 30.1 months for the SRC group and 43.7 months for the NMAC group (P=0.141). Involvement of the left side of the colon (73.3% vs. 26.7%, P=0.003) and infiltrative lesions such as Borrmann types 3 and 4 (85.7% vs. 24.0%, P=0.001) were more common in the SRC group than in the NMAC group. The five-year overall survival rate was significantly lower for patients with SRC than for those with NMAC (46.0% vs. 88.7%, hazard ratio, 6.99; 95% confidence interval, 2.33-20.95, P=0.001).

Conclusions

Patients with even resectable primary colorectal SRC had a poorer prognosis than age-, sex-, and stage-matched colorectal NMAC patients.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasms; Adenocarcinoma; Carcinoma, signet-ring cell; General surgery; Survival

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related death in Western countries.1 As the incidence of and mortality due to CRC are also increasing in Asian countries,2,3 CRC is an important worldwide public health issue. Primary signet-ring cell carcinoma (SRC) of the colon and rectum is a rare and distinctive type of cancer. Because SRC patients tend to have a more advanced and unresectable stage at the time of their diagnosis compared with colorectal, non-mucinous adenocarcinoma (NMAC) patients, the prognosis of SRC is generally poor.4,5,6,7,8 This poor prognosis may be associated with the lower curative resection rate of this cancer type and a higher incidence of an advanced stage at the time of detection, rather than with the actual tumor histology. A comparative analysis confined to SRC and NMAC tumors at the "resectable" stage can provide more accurate information regarding the prognosis of SRC by excluding the influence of possible unresectability. Therefore, we attempted to investigate the prognosis of SRC patients who underwent curative surgery by comparing them with age-, sex-, and stage-matched NMAC patients.

METHODS

1. Patients

The medical records of all patients who were diagnosed with primary SRC of the colorectum at Asan Medical Center between January 2003 and December 2011 were retrospectively reviewed. To accurately define the SRC, all surgical specimens with the possibility of a diagnosis of SRC were additionally reviewed by two pathologists (S.A.K. and Y.S.P.). We excluded patients with only mucinous tumor components. Among the 40 patients identified as meeting our criteria, 19 underwent curative surgery. We excluded 4 SRC patients under the age of 40 as there were very few NMAC cases for comparison. Age- (±3 years), sex-, and stage-matched controls were randomly recruited from NMAC patients whose calendar-year of surgery was similar to SRC patients (±4 years). Patients with tumors with any mucinous component and patients with risk factors including colorectal polyposis syndrome and IBD were excluded from the control group. Finally, the clinicopathological data of 15 patients were reviewed and compared with the data of 75 NMAC patients matched by age, sex, and pathologic stage.

2. Clinical and Pathological Features

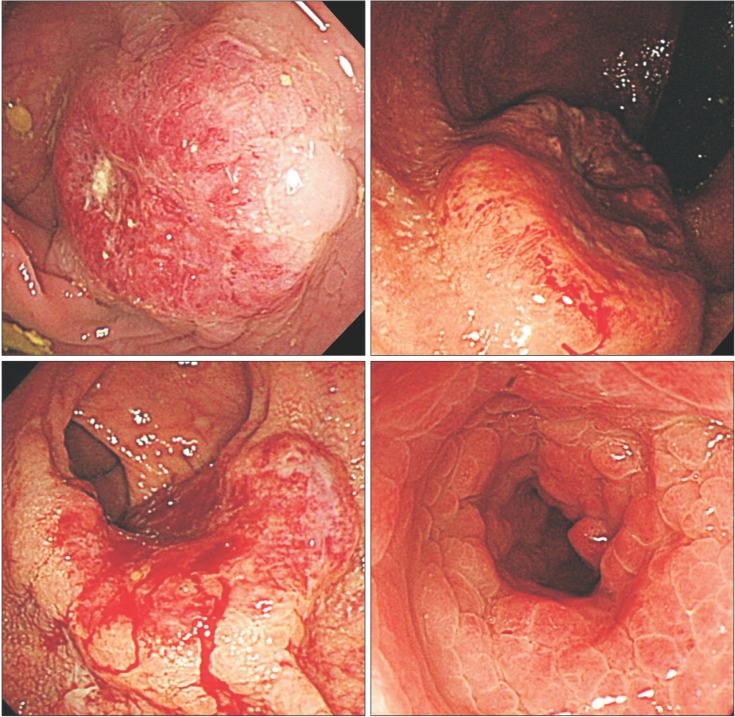

Patients' demographic, tumor, and treatment-related characteristics were then evaluated by comparing their tumor histology and location. Patient-related factors included sex, age, and the year of their diagnosis. Tumor characteristics included gross features (Fig. 1), location, stage (American Joint Committee on Cancer [AJCC] Staging Manual, 7th edition), and grade. The right colon was defined as the splenic flexure and the more proximal portions of the colon. The left colon was defined as the rectum, sigmoid colon, and descending colon up to but not including the splenic flexure. Intraoperative and clinical follow-up data were reviewed. The Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center approved this retrospective study (IRB no.: 2014-0550).

Fig. 1. Borrmann classification of colorectal cancer. (A) A case of Bormann type I (polypoid type) non-mucinous adenocarcinoma; (B) A case of Bormann type II (ulcerofungating type) signet-ring cell carcinoma (SRC); (C) A case of Bormann type III (ulceroinfiltrative type) SRC; and (D) A case of Bormann type IV (infiltrative type) SRC.

3. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as medians with ranges; discrete data are tabulated as numbers and percentages. Univariate analysis was performed using conditional logistic regression modeling in order to account for the clustering of matched pairs. In the matched cohort, the risk of each outcome was compared using the Cox regression model with robust standard errors, which accounted for the clustering of matched pairs. SAS software (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to perform all analyses. In this study, P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. Characteristics of the Study Population

This study included a total of 90 study subjects, 15 in the SRC group and 75 in the NMAC control group. The mean patient age at the time of surgery was 56.0 years (±9.5) and 55.8 years (±9.8) for the study and control groups, respectively. Abdominal pain was the most common presenting symptom in both groups, although it occurred in a higher proportion of the SRC group than in the NMAC group. Twenty-eight percent of the patients in the NMAC group were asymptomatic and were diagnosed during screening colonoscopy, while there were no asymptomatic patients in the SRC group. There were no significant differences between the patient groups regarding sex and the preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen levels (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients and Controls.

| Variable | SRC group (n=15) | NMAC group (n=75) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presenting symptoms | 0.090 | ||

| Abdominal pain | 9 (60.0) | 32 (42.7) | |

| Hematochezia | 5 (33.3) | 13 (17.3) | |

| Obstructive symptoms† | 7 (46.7) | 9 (12.0) | |

| None | 0 (0.0) | 21 (28.0) | |

| CEA (ng/mL), median (range) | 3.2 (1.5-9.4) | 1.9 (1.2-3.2) | 0.086 |

| Location | |||

| Right colon/Left colon | 4 (27.7)/11 (73.3) | 55 (73.3)/20 (26.7) | 0.003 |

| Synchronous adenoma | 3 (20.0) | 37 (49.3) | 0.045 |

| Endoscopic feature | 0.001 | ||

| Early colon cancer | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | |

| Borrmann type 1 | 1 (7.1) | 6 (8.0) | |

| Borrmann type 2 | 1 (7.1) | 50 (66.7) | |

| Borrmann type 3 | 6 (42.9) | 17 (22.7) | |

| Borrmann type 4 | 6 (42.9) | 1 (1.3) |

Values are presented as n (%).

*Conditional logistic regression that accounted for the clustering of matched pairs.

†Obstructive symptoms such as abdominal pain, constipation, and vomiting.

SRC, signet-ring cell carcinoma; NMAC, non-mucinous adenocarcinoma; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

2. Tumor Location and Endoscopic Findings

Involvement of the left colon was significantly more frequent in the SRC group than in the NMAC group (73.3% vs. 26.7%, P=0.003). Synchronous adenoma was more commonly found in the NMAC group (49.3% vs. 20.0%, P=0.045). Infiltrative tumors (Borrmann types 3 and 4) were found significantly more often in the SRC group than in the NMAC group (85.7% vs. 24.0%, P=0.001). Of the 15 SRC patients, 6 (42.9%) had endoscopic stenosis, compared with 36 (48.0%) of the 75 NMAC patients (P=0.690).

3. Tumor, Nodes, Metastasis (TNM) Classification and Stage

The tumor depth in all patients with SRC was T2 or greater (T2 in 1 patient, T3 in 9 patients, T4a in 1 patient, and T4b in 2 patients). Lymph node involvement occurred in 80% of the patients in both groups. In both groups, 6.7% of the patients were diagnosed at stage I, 13.3% at stage II, and 80.0% at stage III.

4. Pathologic Features

The mean tumor size in the SRC group was significantly larger than that in the NMAC group (7.59±2.90 cm vs. 5.37±2.19 cm, P=0.003). As microsatellite instability (MSI) data were not available for 19 patients, these patients were excluded from this analysis. High-frequency MSI was found in 3 of 11 SRC patients (27.3%) and in 10 of 60 NMAC patients (16.7%). There were no significant differences between patients with SRC and matched NMAC patients regarding lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, and MSI (Table 2).

Table 2. Pathologic Characteristics of Patients and Controls.

| Variable | SRC group (n=15) | NMAC group (n=75) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size (cm) | 7.59±2.90 | 5.37±2.19 | 0.003 |

| Invasion depth | 0.060 | ||

| T1 and T2 | 3 (20.0) | 6 (8.0) | |

| T3 | 9 (60.0) | 63 (84.0) | |

| T4 | 3 (20.0) | 6 (8.0) | |

| Lymph node status | 0.994 | ||

| N0 | 3 (20.0) | 15 (20.0) | |

| N1 | 4 (26.7) | 51 (68.0) | |

| N2 | 8 (53.3) | 9 (12.0) | |

| Involvement of resection margin | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.994 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 7 (46.7) | 25 (33.3) | 0.336 |

| Perineural invasion | 6 (40.0) | 17 (22.7) | 0.143 |

| MSI | 3/11 (27.3) | 10/60 (16.7) | 0.486 |

Values are presented as mean±SD or n (%).

*Conditional logistic regression that accounted for the clustering of matched pairs.

SRC, signet-ring-cell carcinoma; NMAC, non-mucinous adenocarcinoma; MSI, microsatellite instability.

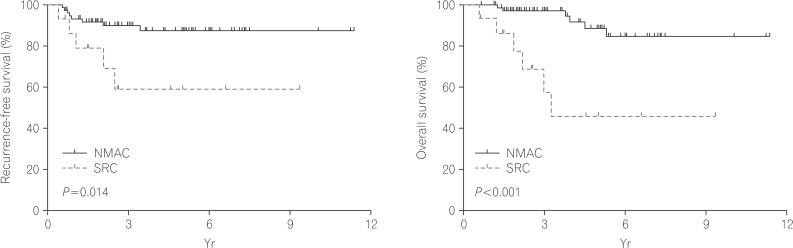

5. Postoperative Survival

The clinical outcomes are described in Table 3. The median follow-up duration was 30.1 months for the SRC group and 43.7 months for the NMAC group (P=0.141). The recurrence-free survival time (Fig. 2) was significantly poorer in the SRC group compared with the NMAC group. The cumulative survival rates for patients with SRC were 93.3%, 57.4%, and 46.0% at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively. In comparison, the cumulative survival rates for patients with NMAC were 100.0%, 97.2%, and 88.7% at 1, 3, and 5 years, respectively. The overall survival rate (Fig. 2) of patients with SRC was less than that for those with NMAC (P<0.001). In univariate analysis, the hazard ratio for death was 6.99 for the SRC group (95% CI, 2.33-20.95; P=0.001) compared with the NMAC group.

Table 3. Clinical Courses and Outcomes.

| Variable | SRC group (n=15) | NMAC group (n=75) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up duration (mo), median (range) | 30.09 (6.74-112.07) | 43.73 (7.75-136.28) | 0.141 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 14 (93.3) | 70 (93.3) | 1.000 |

| Recurrence after resection | 5 (33.3) | 8 (10.7) | 0.038 |

| Mortality | 6 (40.0) | 5 (6.7) | 0.004 |

Values are presented as n (%).

*Conditional logistic regression that accounted for the clustering of matched pairs.

SRC, signet-ring-cell carcinoma; NMAC, non-mucinous adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 2. Kaplan-Meier survival curves comparing the recurrence-free (A) and overall survival (B) of patients with signet-ring-cell carcinoma (SRC) and patients with non-mucinous adenocarcinoma (NMAC) (log-rank test).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective observational study, we found that even in patients with resectable primary colorectal SRC, the prognosis was poorer compared with that of age-, sex-, and stage-matched colorectal NMAC patients.

The reported clinicopathological features of SRC or mucinous colorectal adenocarcinomas are variable and remain controversial. Previous studies indicated that survival differences in patients with mucinous components could be associated with differences in the tumor stage rather than with the pathologic factors.8,9 However, SRC has a poor prognosis independent of the tumor stage, as has been observed in a relatively large number of patients.10,11 The present study clarified that patients with SRC did have a poor overall survival rate compared to the matched NMAC patients, and these findings are in accordance with the results of a previously published report.10,11,12,13

Although there were no substantial differences between patients with SRC and the age-, sex-, and stage-matched NMAC patients regarding lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, and MSI, the overall survival rate of the SRC group was significantly worse than that of the NMAC group. The aggressiveness of infiltrating growth may partially explain the poor prognosis. In our study, 85.7% of the SRC patients presented with a diffusely infiltrative endoscopic feature. Borger et al.12 suggested that SRC was associated with an increased depth of invasion and a poor prognosis and that signet-ring cells showed disturbance of the cadherin-catenin complex. Signet-ring cells are usually present as single cells or in loose clusters, and this suggests a disturbance in cell-cell adhesion. The infiltrating cells may be arranged singly or in loose clusters, and they progress diffusely through the colon. The poor prognosis may partially be attributed to this intramural growth without penetration. Therefore, patients with resectable primary colorectal SRC may require more aggressive adjuvant chemotherapy.

In accordance with the results of previous studies,14,15,16 the current study demonstrated a higher incidence of scirrhous carcinoma in the SRC group than in the NMAC group (42.9% vs. 1.3%). These endoscopic findings might lead to symptoms of intestinal obstruction. In addition, the scope could not be passed beyond the scirrhous carcinoma, and this could contribute to the discrepancy in the synchronous adenoma rate between the SRC and NMAC groups in this study (20.0% vs. 49.3%).

Previous studies have reported controversial results regarding the major anatomic site of SRC.10,17,18,19,20 In our study, the most common location for SRCs was the left colon. In contrast to the current results, previous reports have indicated the right colon as the major anatomic site for SRC.10,11,17,19,21 The reason for this disagreement remains unclear, although the difference in the race/ethnicity of the patients or the small sample size might partly explain the discrepancy. In addition, among the control patients in the current study, right colon cancer was more common, which is not in accordance with previous studies.22,23 Therefore, these results need to be interpreted carefully since selection bias and subsequent confounding can be an issue.

A large number of MSI-high SRCs have been reported to share the same clinicopathological features as other MSI-high cancers.24,25,26,27 However, MSI status did not appear to be a significant predictor of survival in colorectal SRC.24 In our study, there were only 3 SRC patients whose tumors had high-frequency MSI (3 of 11), and none of these patients experienced recurrence or died, which precluded a subgroup analysis. These slightly conflicting data require further study, and the clinical significance remains to be evaluated.

Our study has several limitations. First, the numbers of study subjects were not sufficient to permit analysis of various epidemiological features. The small sample size precluded a multivariate analysis. Second, this was a retrospective study, and therefore the treatment strategy, selected according to the physician's preference and choice, was not controlled. The follow-up period after surgery may not have been sufficient. Third, differences, albeit subtle, may exist between patients with SRCs and NMACs regarding the depth of invasion, and these differences might contribute to a poor outcome within the SRC group. Fourth, our control group was randomly selected from subjects who underwent surgery for NMAC. Because of selection bias, control subjects may not perfectly typify the general NMAC patients. We also did not consider data of patients younger than 40 years of age as we could not find age-matched controls. Further investigation will be necessary in order to determine the clinical features of young patients with SRC.

In conclusion, patients with SRC demonstrated both a poorer overall survival rate and a poorer recurrence-free survival rate compared with the matched NMAC patients. Therefore, more vigorous postoperative surveillance and intense adjuvant therapy should be considered in SRC patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to thank Gwi Hong Jeong, Yeosu Jeil Hospital, for contributions to the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung JJ, Lau JY, Goh KL, Leung WK Asia Pacific Working Group on Colorectal Cancer. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in Asia: implications for screening. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:871–876. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byeon JS, Yang SK, Kim TI, et al. Colorectal neoplasm in asymptomatic Asians: a prospective multinational multicenter colonoscopy survey. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:1015–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.12.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Secco GB, Fardelli R, Campora E, et al. Primary mucinous adenocarcinomas and signet-ring cell carcinomas of colon and rectum. Oncology. 1994;51:30–34. doi: 10.1159/000227306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Messerini L, Palomba A, Zampi G. Primary signet-ring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:1189–1192. doi: 10.1007/BF02048335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tung SY, Wu CS, Chen PC. Primary signet ring cell carcinoma of colorectum: an age- and sex-matched controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2195–2199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nozoe T, Anai H, Nasu S, Sugimachi K. Clinicopathological characteristics of mucinous carcinoma of the colon and rectum. J Surg Oncol. 2000;75:103–107. doi: 10.1002/1096-9098(200010)75:2<103::aid-jso6>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JS, Hsieh PS, Hung SY, et al. Clinical significance of signet ring cell rectal carcinoma. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19:102–107. doi: 10.1007/s00384-003-0515-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu CS, Tung SY, Chen PC, Kuo YC. Clinicopathological study of colorectal mucinous carcinoma in Taiwan: a multivariate analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1996.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang H, O'Connell JB, Maggard MA, Sack J, Ko CY. A 10-year outcomes evaluation of mucinous and signet-ring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1161–1168. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0932-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyngstrom JR, Hu CY, Xing Y, et al. Clinicopathology and outcomes for mucinous and signet ring colorectal adenocarcinoma: analysis from the National Cancer Data Base. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2814–2821. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2321-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Börger ME, Gosens MJ, Jeuken JW, et al. Signet ring cell differentiation in mucinous colorectal carcinoma. J Pathol. 2007;212:278–286. doi: 10.1002/path.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen JS, Hsieh PS, Chiang JM, et al. Clinical outcome of signet ring cell carcinoma and mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colon. Chang Gung Med J. 2010;33:51–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizushima T, Nomura M, Fujii M, et al. Primary colorectal signet-ring cell carcinoma: clinicopathological features and postoperative survival. Surg Today. 2010;40:234–238. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-4057-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song W, Wu SJ, He YL, et al. Clinicopathologic features and survival of patients with colorectal mucinous, signet-ring cell or non-mucinous adenocarcinoma: experience at an institution in southern China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:1486–1491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pyo SH, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, et al. Clinical and Colonoscopic Characteristics of Primary Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma in Colorectum. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;33:278–284. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nissan A, Guillem JG, Paty PB, Wong WD, Cohen AM. Signetring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum: a matched control study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:1176–1180. doi: 10.1007/BF02238570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makino T, Tsujinaka T, Mishima H, et al. Primary signet-ring cell carcinoma of the colon and rectum: report of eight cases and review of 154 Japanese cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 2006;53:845–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee WS, Chun HK, Lee WY, et al. Treatment outcomes in patients with signet ring cell carcinoma of the colorectum. Am J Surg. 2007;194:294–298. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sung CO, Seo JW, Kim KM, Do IG, Kim SW, Park CK. Clinical significance of signet-ring cells in colorectal mucinous adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:1533–1541. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ooi BS, Ho YH, Eu KW, Seow Choen F. Primary colorectal signet-ring cell carcinoma in Singapore. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71:703–706. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-1433.2001.02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim KH, Yang SS, Yoon YS, Lim SB, Yu CS, Kim JC. Validation of the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor-node-metastasis (AJCC TNM) staging in patients with stage II and stage III colorectal carcinoma: analysis of 2511 cases from a medical centre in Korea. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:e220–e226. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park HC, Shin A, Kim BW, et al. Data on the characteristics and the survival of korean patients with colorectal cancer from the Korea central cancer registry. Ann Coloproctol. 2013;29:144–149. doi: 10.3393/ac.2013.29.4.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kakar S, Smyrk TC. Signet ring cell carcinoma of the colorectum: correlations between microsatellite instability, clinicopathologic features and survival. Mod pathol. 2005;18:244–249. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kazama Y, Watanabe T, Kanazawa T, Tada T, Tanaka J, Nagawa H. Mucinous carcinomas of the colon and rectum show higher rates of microsatellite instability and lower rates of chromosomal instability: a study matched for T classification and tumor location. Cancer. 2005;103:2023–2029. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leopoldo S, Lorena B, Cinzia A, et al. Two subtypes of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the colorectum: clinicopathological and genetic features. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:1429–1439. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9757-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim ER, Kim YH. Clinical application of genetics in management of colorectal cancer. Intest Res. 2014;12:184–193. doi: 10.5217/ir.2014.12.3.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]