Highlights

-

•

A relatively rare case of the cutaneous sinus tract in the submental region, derived from the lower second molar, was misdiagnosed as inverted follicular keratosis and thyroglossal duct cyst.

-

•

The patient previously underwent punch resection under local anesthesia, resulting in a histopathological diagnosis of inverted follicular keratosis.

-

•

Computed tomography (CT) and fistulography indicated that the cutaneous lesion was linked to the periapex of the left mandibular second molar.

-

•

Diagnostic imaging is essential in ensuring accurate assessment of the cause of cutaneous sinus tract.

Keywords: Cutaneous dental sinus tract, Misdiagnosis, Dental etiology, Dental pulp necrosis, Inverted follicular keratosis, Thyroglossal duct cyst, Root canal treatment, Surgical extractions

Abstract

Introduction

Odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract is a relatively rare occurrence that can be complicated to diagnose. The presence of a cutaneous lesion is often not even partly associated with a dental etiology because of the less frequency of occurrence in the case of dental symptoms. Consequently, the underlying dental cause is often missed leading to inappropriate diagnosis and treatment.

Case presentation

Here, we report the case of a 45-year-old man who presented with a persistent lesion of the cervical region. At the time of presentation, the lesion had been present for approximately one year with a gradual increase in size but no specific symptoms. The patient had previously undergone punch resection under local anesthesia, which resulted in a histopathological diagnosis of inverted follicular keratosis. A diagnosis was made of an odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract secondary to chronic apical periodontitis of the left mandibular second molar.

Discussion

Cutaneous sinus tract in the face and neck is most likely to develop intraorally. Root canal treatment or surgical extractions are the common treatment choices. A previously reported review of 137 cases found that 106 (77%) were treated by extraction and 27 (20%) were treated by surgical or conservative nonsurgical endodontic therapy.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis of cutaneous sinus tract using proper aid is responsible for shortening the treatment duration and avoiding unnecessary treatment.

1. Introduction

Odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract in the facial and cervical skin is known to occur because of dental pulp necrosis and chronic periapical periodontitis [1]. It continues to be a diagnostic dilemma as its definite diagnosis frequently takes prolonged periods and involves multiple investigations [2]. This major delay in diagnosis occurs because the cutaneous lesion is not always closely aligned to the underlying infection [3] and only about half of the affected patients reported a toothache [4]. In general, patients are unaware that there is an underlying dental etiology as their first presentation to physicians is most commonly for seeking treatment of the cutaneous lesion [5]. Due to the incorrect diagnosis and treatment of the infectious dental source, approximately half of the patients face multiple unsuccessful attempts at incision, drainage, and long-term use of antibiotics [5], even radiotherapy [6], electrodesiccation [7] or cancer-directed therapy [8]. The subsequent failure of these inappropriate treatments leads to the recurrence of the underlying problem. Odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract most commonly originates from the mandibular molars, often arising in the submandibular region or the cheek with occasional presentation in the submental region [20]. Here, we report a relatively rare case of the cutaneous sinus tract in the submental region derived from the lower second molar, which was misdiagnosed as inverted follicular keratosis and thyroglossal duct cyst.

2. Case presentation

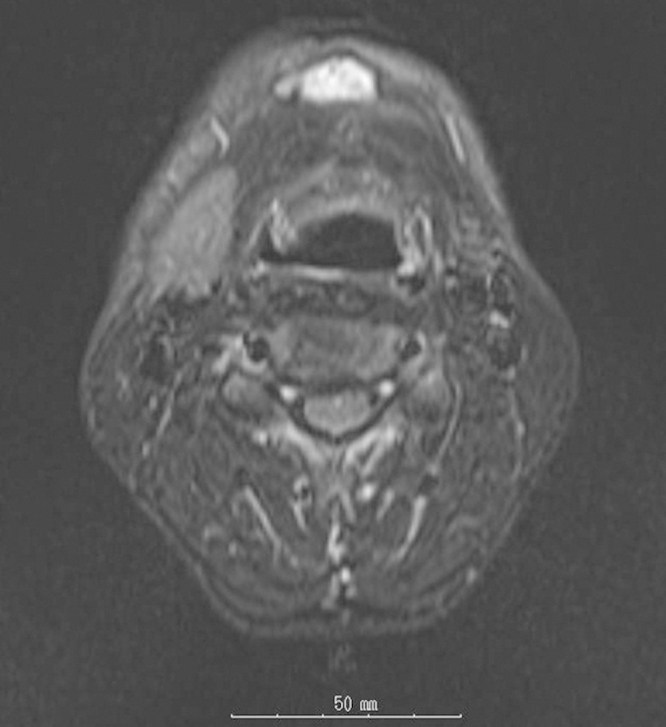

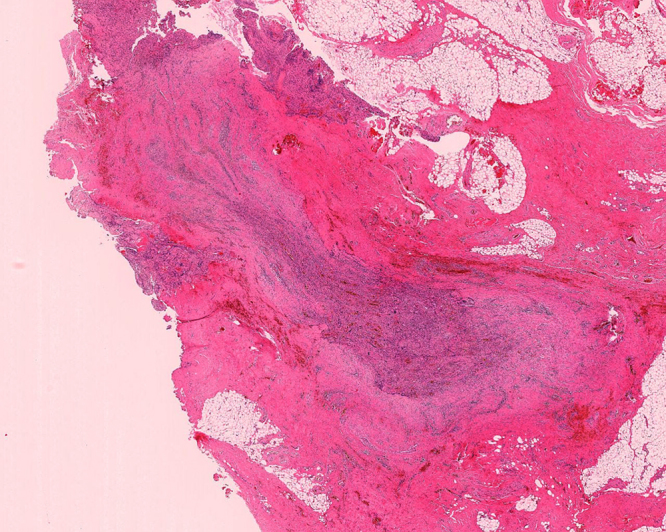

A 45-year-old male patient reported to the Department of Oral-Maxillofacial Surgery, Dentistry and Orthodontics at Tokyo University Hospital, Tokyo, Japan in January 2014 by referral, with the main complaint of a persistent lesion of the cervical region. The patient had first become aware of the lesion in February 2013; however, he had not sought any medical attention as he did not observe any specific symptoms. Since February 2013, the lesion had gradually increased in size, and punch resection was performed under local anesthesia in April 2013. The histopathological diagnosis of the lesion, i.e. inverted follicular keratosis, was performed at another hospital. Although the residual was strongly suspected, he was referred to a plastic reconstructive surgery. Extraoral examination showed approximately 20 mm × 20 mm mass in the submental region. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a well-demarcated cyst located close to the hyoid bone, with high signal intensity present at the partial center in the T1-weighted image and entirely in the T2-weighted image (Fig. 1). Excision of the thyroglossal duct was performed under general anesthesia in July 2013. Histopathological examination did not detect any cystic structure, thyroid gland follicle or mucus component with fibrous scar accounting for the majority of the excised tissue (Fig. 2). The cutaneous wound dehisced in October 2013, following which the patient consulted our department for an intraoral evaluation.

Fig. 1.

Pre-operative MRI revealed a well-demarcated cyst close to the hyoid bone. High signal intensity was found at the partial center in T1-weighted image and entirely at T2-weighted image. This was filmed using short TI inversion recovery imaging.

Fig. 2.

Cystic structure or thyroid gland follicle, mucus component were not histopathologically detected, and inflammatory cells were mostly occupied; the latter resection sample is more scarred than the former. (Hematoxylin and eosin staining, 1.25× original magnification).

Extraorally, approximately 10 mm suture was dehiscent at the submental region, and a gentle pressure on the surrounding tissue produced suppurative drainage from the central punctum (Fig. 3). Gingival swelling and redness were intraorally unclear at the left mandibular molars. The periapical radiographic examination indicated diffused radiolucency measuring 6 mm × 7 mm at the apex of the left mandibular second molar (Fig. 4). Computed tomography (CT) and fistulography indicated that the cutaneous lesion was linked to the periapex of the left mandibular second molar (Fig. 5). An odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract secondary to chronic apical periodontitis of the left mandibular second molar was diagnosed.

Fig. 3.

Extraorally, approximately 10 mm suture was dehiscent at the submental region, and gentle pressure on the surrounding tissue produced suppurative drainage from the central punctum.

Fig. 4.

Periapical radiograph examination indicated 6 mm × 7 mm radiolucency at the apex of the left mandibular second molar.

Fig. 5.

Fistulography confirmed that the cutaneous lesion communicated with the periapex of the left mandibular molars.

Visual inspection revealed evidence of a caries lesions extending subgingivally in the distal aspect of the left mandibular wisdom tooth. The tooth was extracted under local anesthesia in February 2014. It was intraoperatively confirmed that the tract led from the submental lesion to the apex of the left mandibular second molar through a sonde (Fig. 6). Antibiotics were prescribed postoperatively, and the cutaneous lesion closed on the 10th postoperative day.

Fig. 6.

The use of a sonde revealed that the tract was leading from the submental lesion to the apex of the left mandibular second molar.

3. Discussion

Cutaneous sinus tract in the face and neck is most commonly derived from a chronically draining dental infection [9] and is most likely to develop intraorally rather than extraorally. A periapical dental abscess secondary to caries is the major factor behind a large proportion of such cases [10]. It is reported that teeth associated with sinus tracts accounted for 12.7% of those requiring endodontic treatment and having periapical pathosis, with approximately 1% of them being extraoral [11]. Progression is a slow process, with the infection most often passing through the cancellous alveolar bone along the path of least resistance, with an acute presentation after reaching a critical point. The direction of spread of inflammation is defined by the muscles and fascial planes, guiding the pus to a certain area where it can accumulate [12]. The sinus drains cutaneously if the inflammation tracks out of the jaw above the maxillary muscle attachments or below the mandibular muscle attachments. Approximately 80% of cases involve mandibular teeth, half of which were incisors. Eventually, it is formed mostly in the chin or submental region. Drainage sites are usually anatomically close to the causal tooth while the cutaneous sinus tract derived from periapical abscesses of mandibular premolars or molars commonly occurs in the submandibular sites, although it is conspicuously rare in the submental region. In previously reported cases, the causative mandibular second molar had concrescence-like malformation [20]. The inflammation of the apex of the left mandibular molar could penetrate the lingual cortical bone of the mandible, spreading more chronically along the fascial plane of the mylohyoid, with the formation of cutaneous lesion at the submental site.

Odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract has a soft, erythematous, and slightly depressed appearance [3]. Palpation of the surrounding tissue can result in fluid discharge draining through a central opening. The culture of this fluid and sensitivity tests can help establish the diagnosis [5], [13]. The oral dental examination can also include a vitality test and panoramic periapical radiographic examination with gutta-percha cone or a lacrimal probe inserted, which are also important for diagnostic accuracy. These tests can trace the tract from its cutaneous lesion to the point of the origin, which is usually a non-vital tooth [5], [11], [16]. An additional important component for ensuring an accurate diagnosis is careful history-taking, since, previous case reports have suggested that presentation with odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract is more likely to occur in patients with a history of previous dental disease [21]. Careful questioning of the patient about past symptoms, such as oral trauma, periodontal disease, and oral hygiene regimens, may therefore help to establish dental etiology in a newly presenting patient.

The foremost aim of treatment is to eliminate the source of infection. Treatments of choice are root canal treatment or surgical extraction. A previously reported review of 137 cases found that 106 (77%) were treated by extraction and 27 (20%) were treated by surgical or conservative nonsurgical endodontic therapy [22]. Conservative nonsurgical root canal treatment is suggested as the first choice of treatment if the offending tooth is restorable. In a recent study, a persistent extraoral sinus tract originating from a necrotic pulp was successfully cured by single-visit endodontics rather than the traditional multi-visit [14]. The key to successful treatment is ensuring adequate measures to eliminate intracanal microorganisms. Early studies demonstrated that these sinus tracts were lined with epithelium, suggesting that surgical intervention was necessary to ensure recovery [15]. However, subsequent studies have demonstrated that the sinus tract is lined with granulation tissue, indicating that they can be treated with nonsurgical root canal therapy [13], [16]. Inadvertent excision of a cutaneous lesion inevitably recurs, leading to wound dehiscence if the primary odontogenic disease site cannot be completely removed. Therefore, it would be inadequate to use antibiotic treatment alone without treating the causal tooth. Instead, antibiotics should be used as an adjunct to therapy to ensure complete resolution of infection [3]. It is further suggested that if the primary odontogenic aetiology is properly removed, the lesion would close spontaneously in a few weeks without the need for antibiotics [3], [5], [13]. In case the sinus tract remains after eliminating the infectious source, there are chances of occasional occurrence of actinomycosis [13]. In addition, the healing of the cutaneous lesion can result in dimpling and hyperpigmentation leading to a residual tract, which may need cosmetic surgical intervention [13]. In the case reported herein, the caries of the causative left second mandibular molar progressed subgingivally, thus indicating that conservation of this tooth would be quite difficult.

Within this case report, the initial resection sample showed reactive acanthosis in the epidermis and granulation tissue with intense inflammation under the dermis. The later sample indicated more-scarred subcutaneous and dermal inflammatory tissue. Notably, cyst-like structures have been rarely observed in previous reports and were not observed in this case either.

The clinical differential diagnosis should include trauma, foreign body reaction, pyogenic granuloma, fungal and bacterial infections, actinomycosis, osteomyelitis, tuberculosis, gummata of tertiary syphilis, furuncle, epidermal cyst, thyroglossal duct cyst, squamous cell carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma. Other uncommon entities are salivary gland and duct fistula, dacryocystitis, and suppurative lymphadenitis [5], [13], usually without malignancy. Thyroglossal duct cyst is the most common malformation in the neck, constituting 70–75% of all congenital neck masses [17], [18]. It is derived from an epithelial remnant of an embryological tract, the thyroglossal duct, and is most commonly located in the middle neck, adjacent to the hyoid bone [17], [18]. Its palpation reveals an indolent, soft and mobile mass [17], [19]. Approximately one-third of patients experience an infection, which is characterized by cellulitis or an abscess. Eventually, fistulae to the skin or the foramen cecum can be formed secondary to trauma or previous inadequate surgery [17]. Within this case, inspection, palpation, and pre-operative MRI suggested a diagnosis of a cyst or infection within the thyroglossal duct, with odontogenic infection not considered at this point. However, post-operative CT and fistulography indicated that the infection originated from the left mandibular second molar.

4. Conclusion

This case report, therefore, further supports the importance of diagnostic imaging in ensuring accurate assessment of the cause of cutaneous sinus tract.

An odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract is common and has been previously presented in a number of case reports. It is usually presented asymptomatically, thus making it increasingly difficult for the physicians to diagnose it with precision. In addition, accurate diagnosis requires cooperative referral between physicians and dentists, a comprehensive judgment from imaging findings and clinical appearance, and a consideration of the potential of dental etiology. Therefore, the early diagnosis of this rare occurrence is highly important to remove unnecessary treatment, shorten the treatment duration, and reduce the patients’ burden.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interests.

Funding

The authors have no funding or financial relationships to disclose.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent

A written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Authors contribution

Toshihisa Sato and Masaki Igarashi—drafted the manuscript.

Hideyuki Suenaga, Kazuto Hoshi and Tsuyoshi Takato—involved in collecting imaging and histopathological material, reviewing the literature and critically revising the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final paper.

Guarantor

I hereby agree and affirm that I will, as guarantor.

References

- 1.Bender I.B., Seltzer S. The oral fistula: its diagnosis and treatment. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1961;14:1367–1376. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(61)90270-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewin-Epstein J., Taicher S., Azaz B. Cutaneous sinus tracts of dental origin. Arch. Dermatol. 1978;114:1158–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheehan D.J., Potter B.J., Davis L.S. Cutaneous draining sinus tract of odontogenic origin: unusual presentation of a challenging diagnosis. South. Med. J. 2005;98:250–252. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000129936.08493.E0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Held J.L., Yunakov M.J., Barber R.J., Grossman M.E. Cutaneous sinus of dental origin: a diagnosis requiring clinical and radiologic correlation. Cutis. 1989;43:22–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantatore J.L., Klein P.A., Lieblich L.M. Cutaneous dental sinus tract, a common misdiagnosis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2002;70:264–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorsky M., Kaffe I., Tamse A. A draining sinus tract of the chin: report of a case. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1978;46:583–587. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(78)90389-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spear K.L., Sheridan P.J., Perry H.O. Sinus tracts to the chin and jaw of dental origin. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1983;8:486–492. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montgomery D.W. Fistulas from dead teeth simulating dermal epithelioma. Arch. Dermatol. 1940;41:378. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sammut S., Malden N., Lopes V. Facial cutaneous sinuses of dental origin—a diagnostic challenge. Br. Dent. J. 2013;215:555–558. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaban L.B. Draining skin lesions of dental origin: the path of spread of chronic odontogenic infection. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1980;66:711–717. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang T.J., Roan R.T., Lin H.T. Sinus tracts of dental origin: a clinical study. Part I. Gaoxiong Yi Xue Ke Xue Za Zhi. 1990;6:653–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witherow H., Washan P., Blenkinsopp P. Midline odontogenic infections: a continuing diagnostic problem. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2003;56:173–175. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(03)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tidwell E., Jenkins J.D., Ellis C.D., Hutson B., Cederberg R.A. Cutaneous odontogenic sinus tract to the chin: a case report. Int. Endod. J. 1997;30:352–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1997.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satish Kumar K., Subbiya A., Vivekanandhan P., Prakash V., Tamilselvi R. Management of an endodontic infection with an extra oral sinus tract in a single visit: a case report. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013;7:1247–1249. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/5369.3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison J.W., Larson W.J. The epithelized oral sinus tract. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1976;42:511–517. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura Y., Hirayama K., Hossain M., Matsumoto K. A case of an odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract. Int. Endod. J. 1999;32:328–331. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1999.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mondin V., Ferlito A., Muzzi E., Silver C.E., Fagan J.J., Devaney K.O., Rinaldo A. Thyroglossal duct cyst: personal experience and literature review. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2008;35:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sameer K.S., Mohanty S., Correa M.M., Das K. Lingual thyroglossal duct cysts—a review. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76:165–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou J., Walters A., Hage R., Zurada A., Michalak M., Tubbs R.S., Loukas M. Thyroglossal duct cysts: anatomy, embryology and treatment. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2013;35:875–881. doi: 10.1007/s00276-013-1115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varol A., Gülses A. An unusual odontogenic cutaneous sinus tract to the cervical region: a case report. Oral Health Dent. Manag. Black Sea Countries. 2009;8:43–46. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantatore J.L., Klein P.A., Lieblich L.M. Cutaneous dental sinus tract, a common misdiagnosis: a case report and review of the literature. Cont. Med. Ed. 2002;70:264–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cioffi G.A., Terezhalmy G.T., Parlette H.L. Cutaneous draining sinus tract: an odontogenicetiology. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1986;14:94–100. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]