Abstract

tRNA modifications are crucial for efficient and accurate protein synthesis, and modification defects are frequently associated with disease. Yeast trm7Δ mutants grow poorly due to lack of 2'-O-methylated C32 (Cm32) and Gm34 on tRNAPhe, catalyzed by Trm7-Trm732 and Trm7-Trm734 respectively, which in turn results in loss of wybutosine at G37. Mutations in human FTSJ1, the likely TRM7 homolog, cause non-syndromic X-linked intellectual disability (NSXLID), but the role of FTSJ1 in tRNA modification is unknown. Here we report that tRNAPhe from two genetically independent cell lines of NSXLID patients with loss of function FTSJ1 mutations nearly completely lacks Cm32 and Gm34, and has reduced peroxywybutosine (o2yW37). Additionally, tRNAPhe from an NSXLID patient with a novel FTSJ1-p.A26P missense allele specifically lacks Gm34, but has normal levels of Cm32 and o2yW37. tRNAPhe from the corresponding Saccharomyces cerevisiae trm7-A26P mutant also specifically lacks Gm34, and the reduced Gm34 is not due to weaker Trm734 binding. These results directly link defective 2'-O-methylation of the tRNA anticodon loop to FTSJ1 mutations, suggest that the modification defects cause NSXLID, and may implicate Gm34 of tRNAPhe as the critical modification. These results also underscore the widespread conservation of the circuitry for Trm7-dependent anticodon loop modification of eukaryotic tRNAPhe.

Keywords: FTSJ1, intellectual disability, NSXLID, tRNA, 2'-O-methylation, TRM7

Introduction

The numerous post-transcriptional modifications of tRNA are crucial for accurate and efficient translation of the genetic code. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, mutations affecting 16 of the 25 tRNA modifications lead to distinct phenotypes, including lethality for three mutants, and poor growth or temperature sensitivity for six other mutants (Hopper, 2013). Modifications in and around the tRNA anticodon loop (residues 31–39) are particularly important in all organisms (de Crecy-Lagard, et al., 2012), often affecting decoding (Agris, et al., 2007; Murphy, et al., 2004), charging by the cognate tRNA aminoacyl synthetase (Muramatsu, et al., 1988; Putz, et al., 1994), and/or frame maintenance (Bekaert and Rousset, 2005; Urbonavicius, et al., 2001; Waas, et al., 2007), whereas modifications in the body of the tRNA often contribute to folding or stability (Hall, et al., 1989; Helm, et al., 1999; Whipple, et al., 2011; Yue, et al., 1994) and are required to avoid decay by two known degradation pathways (Alexandrov, et al., 2006; Chernyakov, et al., 2008; Kadaba, et al., 2004; Kadaba, et al., 2006; LaCava, et al., 2005; Schneider, et al., 2007; Vanacova, et al., 2005).

Emerging evidence shows that tRNA modifications have important roles in human health. Mutations in nine predicted human homologs of tRNA modification genes have been strongly linked to specific diseases, seven of which are linked to neurological disorders, including six linked to intellectual disability (ID) (Abbasi-Moheb, et al., 2012; Alazami, et al., 2013; Anderson, et al., 2001; Cuajungco, et al., 2003; Fahiminiya, et al., 2013; Freude, et al., 2004; Froyen, et al., 2007; Gillis, et al., 2014; Igoillo-Esteve, et al., 2013; Khan, et al., 2012; Martinez, et al., 2012; Najmabadi, et al., 2011; Ramser, et al., 2004; Slaugenhaupt, et al., 2001; Takano, et al., 2008; Yarham, et al., 2014; Zeharia, et al., 2009). However, the molecular basis of the link between the neurological disorders and mutations in predicted tRNA modification genes is not clear. Indeed, decreased levels of tRNA modifications have only been demonstrated in cells derived from patients with two neurological disorders. First, bulk tRNA from brain tissue and cell lines derived from familial dysautonomia (FD) patients, which is due to mutations in IKBKAP in numerous cases (Anderson, et al., 2001; Cuajungco, et al., 2003; Dong, et al., 2002; Slaugenhaupt, et al., 2001), had reduced levels of the mcm5s2U34 modification and the IKAP protein (Karlsborn, et al., 2014). This result is consistent with the homology between IKAP and the Elp1 subunit of the S. cerevisiae elongator complex (Hawkes, et al., 2002), which is required for cm5U formation (Huang, et al., 2005). Second, tRNA from cells derived from patients with a Dubowitz-like syndrome (characterized by phenotypes including microcephaly and mental and speech delays) linked to an NSUN2 splice-site mutation lacked m5C at residues 34, 48, 49, and 50 (Blanco, et al., 2014; Martinez, et al., 2012), consistent with the activity of the yeast and mammalian homologs (Blanco, et al., 2011; Brzezicha, et al., 2006; Motorin and Grosjean, 1999; Tuorto, et al., 2012). NSUN2 mutations are also linked to other neurological disorders including a Noonan-like syndrome similar to the NSUN2-linked Dubowitz-like syndrome (Fahiminiya, et al., 2013) and autosomal recessive ID (ARID) in four independent families (Abbasi-Moheb, et al., 2012; Khan, et al., 2012).

One of the strongest links between ID and a putative tRNA modification gene is that linking non-syndromic X-linked ID (NSXLID) to mutations in FTSJ1(MIM# 300499), a homolog of yeast Trm7, which catalyzes formation of Cm32 and Nm34 on substrate tRNAs (Pintard, et al., 2002) and is critical for normal function of tRNAPhe (Guy, et al., 2012). Distinct alleles of FTSJ1 from five independent families are linked to NSXLID and each allele results in reduced levels of mRNA or reduced predicted protein function (Freude, et al., 2004; Ramser, et al., 2004; Takano, et al., 2008). In addition, NSXLID is linked to a microdeletion that removes FTSJ1 and SLC38A5 (Froyen, et al., 2007) (Table 1; Supp. Table S1). Moreover, FTSJ1 is the likely human ortholog of the yeast TRM7 gene, since expression of human FTSJ1 under control of the strong PGAL promoter (PGAL-FTSJ1) in a high copy (2µ) plasmid suppresses the severe growth defect of S. cerevisiae trm7Δ mutants (Guy and Phizicky, 2015).

Table 1.

FTSJ1 mutations associated with NSXLID analyzed for tRNA modifications in this study

| FTSJ1 allele | Family | Mutation | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTSJ1Δ | 6 | Deletion of FTSJ1 and SLC38A5 | Loss of FTSJ1 | (Froyen, et al., 2007) |

| FTSJ1 splice site (FTSJ1-ss) | 3 | c.121+1delG | Significant reduction of FTSJ1 mRNA levels | (Freude, et al., 2004) |

| p.A26P | 7 | c.76G>C; p.A26P | Altered FTSJ1 protein function | This study, (Hu, et al., 2015) |

In S. cerevisiae, Trm7 is the central component of a complex modification circuitry required for anticodon loop modification of target tRNAs, wherein Trm7 separately interacts with Trm732 and Trm734 to form Cm32, and Nm34 respectively, both of which are required on tRNAPhe for efficient formation of wybutosine (yW) at m1G37 by other proteins (Fig. 1A)(Guy, et al., 2012; Noma, et al., 2006). Moreover, the same circuitry appears to be conserved in the phylogenetically distant yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, since the nearly lethal phenotype of trm7Δ mutants is suppressed by overproduction of tRNAPhe, since tRNAPhe of trm7Δ mutants likewise lack Cm32, Gm34, and yW37, and since the homologous S. pombe Trm732 and Trm734 proteins are required for the respective Cm32 and Gm34 modifications (Guy and Phizicky, 2015). Indeed, this conserved circuitry might be further extended in eukaryotes since suppression of the growth defect of S. cerevisiae trm7Δ mutants by FTSJ1 expression requires the function of Trm732 or its human homolog THADA to form Cm32 on tRNAPhe (Guy and Phizicky, 2015).

Figure 1.

FTSJ1 mutations associated with NSXLID are defective for 2'-O-methylation on tRNAPhe.

(A) Schematic of the circuitry for tRNAPhe anticodon loop modification in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe. Trm7 acts with Trm732 to form Cm32 and separately with Trm734 to form Gm34, and these modifications in turn drive yW formation at m1G37 on tRNAPhe. Wider arrow from Gm34 indicates that yW formation is more dependent on this modification than on Cm32. Predicted human homologs of Trm7, Trm732, and Trm734 are in brackets.

(B) HPLC traces of nucleosides of tRNAPhe purified from human LCLs derived from FTSJ1-associated NSXLID patients. tRNAPhe isolated from LCLs derived from NSXLID patients with the indicated FTSJ1 alleles, and from control LCLs, was digested to nucleosides and analyzed by HPLC as described in Materials and Methods. (ss), splice site mutation; (wt) wild type.

(C) Quantification of tRNAPhe nucleoside analysis from panel B. (*), levels below threshold of detection.

(D) Analysis of o2yW levels on tRNAPhe purified from LCLs of FTSJ1-associated NSXLID patients. Nucleosides of tRNAPhe from indicated LCLs were analyzed as in panel B under conditions optimized for evaluating o2yW modification.

Although it is well established that human FTSJ1 mutations cause NSXLID, the connection between FTSJ1 and tRNA modifications is not known in human cells, or in any metazoan. Indeed, it is not necessarily true that FTSJ1 modifies human tRNAs based on complementation of a yeast mutant when FTSJ1 is expressed at high levels.

Here we show that cell lines derived from NSXLID patients bearing genetically distinct disease-causing FTSJ1 mutations have pronounced defects in 2'-O-methylation of the anticodon loop of tRNAs, with reduced levels of peroxywybutosine (o2yW37) on tRNAPhe. These findings provide strong evidence that FTSJ1 catalyzes Cm32 and Nm34 modification in humans, and further support the conserved circuitry for tRNAPhe anticodon loop modification. Intriguingly, tRNAPhe from human cell lines with a novel missense FTSJ1-p.A26P mutation (NM_012280.2, c.76G>C, p.A26P; nucleotide numbering is based on cDNA sequence) or from the corresponding yeast trm7-A26P mutant lacks Gm34 but retains Cm32, apparently due to selective loss of substrate recognition and/or catalysis, rather than to reduced expression or protein interactions. These results strongly suggest that FTSJ1-associated NSXLID is due to lack of modifications of the anticodon loop of substrate tRNAs, and suggest the possibility that if tRNAPhe is the important human FTSJ1 target (as is true in two phylogenetically distant model yeast organisms), that lack of only Gm34 of tRNAPhe might be sufficient to trigger NSXLID.

Materials and Methods

Sequencing and identification of the FTSJ1-p.A26P variant

DNA extracted from whole-blood (QIAamp DNA blood maxi kit; Qiagen, Limburg, Netherlands) was part of a large X-chromosome exome sequencing study (Hu, et al., 2015), with one affected individual sequenced from this family (III-2, HiSeq; Illumina, San Diego, USA). Confirmation of the FTSJ1 gene (NM_012280.2, c.76G>C, p.A26P; nucleotide numbering based on cDNA sequence) variant and segregation analysis by Sanger sequencing was carried out using standard methods. FTSJ1 exon 2 DNA was amplified and sequenced using the following primers; F - 5’- GCA GTG GAG CCT GAG AGT TC-3’ and R - 5’- CTA TCT TCC TGC CTG TCT CCC T-3’.

Generation of lymphoblastoid cell lines

LCLs derived from patients bearing a c.121+1delG mutation in FTSJ1(Supp. Table S1; FTSJ1-ss; family 3), and from a patient bearing an FTSJ1 deletion (FTSJ1Δ; family 6) have been described previously (Freude, et al., 2004; Froyen, et al., 2007). Other LCLs were generated using standard methods.

Yeast strains and plasmids

Yeast strains are listed in Supp. Table S2. Plasmids used in this study are listed in Supp. Table S3. See Supp. Methods for detailed information on construction of strains and plasmids.

tRNA purification and northern blot analysis

For a detailed description of cell growth conditions and RNA preparation, see Supp. Methods. Briefly, RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Life Technologies) according to manufacturer's instructions. Extraction of RNA using phenol for northern analysis under acidic conditions to preserve aminoacylation was previously described (Alexandrov, et al., 2006). Low molecular weight RNA was extracted from yeast cells as previously described (Jackman, et al., 2003), and appropriate 5’ biotinylated oligonucleotides were used to purify tRNA from yeast and human RNA preparations as previously described (Jackman, et al., 2003).

HPLC analysis of tRNA

Purified tRNA was digested with P1 nuclease and phosphatase as previously described (Jackman, et al., 2003), and nucleosides were subjected to HPLC analysis essentially as previously described (Jackman, et al., 2003). Nucleosides from tRNAPhe were separated by HPLC at pH 7.0 to maximize separation of Gm and m1G, as previously described (Guy, et al., 2012), and o2yW was separated by HPLC as previously described (Noma, et al., 2006).

Immunoblot analysis

Yeast crude extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). MORF-tagged and PT-tagged constructs were detected with rabbit polyclonal anti-protein A (Sigma, 1:5,000), followed by incubation with goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Bio-Rad, 1:10,000), and visualization with Amersham ECL Plus (GE Healthcare). The 9myc tag was detected with mouse monoclonal anti-[c-myc] (Roche, 1:10,000), followed by incubation with goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Bio-Rad, 1:10,000), and visualization.

Affinity purification of tagged proteins

MORF-tagged and PT-tagged proteins were purified by affinity purification with IgG Sepharose followed by elution with GST-3C protease, and removal of the protease using glutathione Sepharose resin, essentially as previously described (Quartley, et al., 2009).

Clinical description

For a detailed clinical description, see Supp. Methods. This research was approved by the Women's and Children's Health Network Human Research Ethics Committee.

Results

FTSJ1 is required for Cm32 and Gm34 modification of tRNAPhe

To determine if patients with FTSJ1-associated NSXLID have reduced 2'-O-methylation in their tRNAs, we analyzed tRNAPhe purified from lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) derived from a patient with an X chromosome microdeletion of FTSJ1 and SLC38A5 (FTSJ1Δ, family 6, Table 1, Supp. Table S1) (Froyen, et al., 2007) and from two brothers with a splice site mutation in FTSJ1(c.121+1delG, FTSJ1-ss, family 3, Table 1, Supp. Table S1) (Freude, et al., 2004), as well as from two control LCLs derived from healthy individuals. We found that tRNAPhe purified from the FTSJ1Δ LCL had no detectable Cm or Gm modification (<0.03 moles/mole for each vs. 0.72 to 0.74 moles/mole for Cm and 0.69 to 0.74 moles/mole for Gm), and that tRNAPhe from both of the FTSJ1-ss LCLs had undetectable Gm and a small, but detectable, amount of Cm (0.07 and 0.05 moles/mole, respectively), whereas levels of Ψ, m5C, m1A, m7G, and m2G were similar to those from control LCLs (Table 2, Fig. 1B,C). Thus, these data strongly indicate that FTSJ1 is the homolog of yeast TRM7 that is responsible for 2'-O-methylation of tRNAPhe in humans, and link FTSJ1-associated NSXLID with tRNA modification defects.

Table 2.

HPLC analysis of tRNAPhe nucleoside content from human LCLs derived from patients with mutations in FTSJ1

| cell line FTSJ1 |

(control 1) wild type |

(control 2) wild type |

(F6) Δ |

(F3:1) ss |

(F3:2) ss |

(F7) p.A26P |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mod. | mol. exp. |

||||||

| Cm | 1 | 0.74 ± 0.14 | 0.72 ± 0.05 | <0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.002 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.63 ± 0.14 |

| Gm | 1 | 0.74 ± 0.04 | 0.69 ± 0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 | <0.03 |

| m1G | 0 | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.09 | 0.74 ± 0.06 | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.65 ± 0.03 | 0.29 ± 0.08 |

| Ψ | 4 | 3.12 ± 0.29 | 3.21 ± 0.16 | 3.17 ± 0.31 | 3.16 ± 0.27 | 3.31 ± 0.33 | 3.32 ± 0.33 |

| m5C | 1 | 0.68 ± 0.14 | 0.70 ± 0.08 | 0.62 ± 0.13 | 0.72 ± 0.08 | 0.73 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.12 |

| m1A | 2 | 0.84 ± 0.11 | 0.94 ± 0.13 | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 0.83 ± 0.13 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 0.91 ± 0.17 |

| m7G | 1 | 0.48 ± 0.15 | 0.46 ± 0.11 | 0.39 ± 0.11 | 0.48 ± 0.16 | 0.44 ± 0.08 | 0.46 ± 0.12 |

| m2G | 1 | 0.77 ± 0.10 | 0.81 ± 0.10 | 0.78 ± 0.07 | 0.78 ± 0.08 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.80 ± 0.09 |

| o2yW | 1 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 1.00 ± 0.12 | 0.16 ± 0.08 | 0.22 ± 0.06 | 0.23 ± 0.09 | 0.80 ± 0.011 |

Mean and standard deviation based on three individual growths and RNA preparations.o2yW values are relative to control 2. mol. exp.; moles expected.

We also found that FTSJ1Δ and FTSJ1-ss LCLs have reduced levels of the o2yW modification of m1G37 of tRNAPhe. Thus, we observed an increase in m1G on tRNAPhe from LCLs with these FTSJ1 mutations compared to control LCLs (0.65 – 0.74 moles/mole, compared to 0.15 – 0.42 moles/mole, Table 2, Fig. 1B,C), and a corresponding decrease in relative amounts of o2yW (to 0.16 – 0.23 compared to control values of 0.6 and 1.0. Table 2, Fig. 1D). This result implies that, as for yW37 formation in both S. cerevisiae and S. pombe (Guy and Phizicky, 2015; Guy, et al., 2012), o2yW37 formation from m1G is stimulated by Cm32 and/or Gm34 of tRNAPhe.

We also analyzed Cm levels on tRNATrp, which has Cm32 and Cm34 in five of six characterized tRNATrp species from eukaryotes (Guy and Phizicky, 2015; Machnicka, et al., 2013), including the mammal Bos taurus (Fournier, et al., 1978) and is modified at both residues by Trm7 in S. cerevisiae (Pintard, et al., 2002). Since tRNATrp purified from the FTSJ1Δ LCL lacked Cm, whereas tRNATrp from a control LCL had substantial amounts of Cm (<0.03 vs. 1.06 moles/mole, Supp. Table S4), we infer that tRNATrp is modified by FTSJ1 in humans.

As in yeast (Guy, et al., 2012), the lack of modification in LCL tRNAs that is due to FTSJ1 mutations does not appear to affect the amounts or the charging levels of substrate tRNAs. Thus, levels of tRNAPhe and tRNATrp from LCLs with FTSJ1-ss or FTSJ1Δ mutations appear to be normal relative to wild type LCLs, as determined by Northern blot analysis (Supp. Fig. S1). Furthermore, lack of these modifications does not appear to affect tRNA charging in these cells, since there is as much or more charged tRNAPhe and tRNATrp relative to uncharged tRNA in the mutant LCLs as in the wild type LCLs (Supp. Fig. S1).

Identification of a novel, missense FTSJ1 variant c.76G>C; p.A26P in a family with NSXLID

By investigation of the X-chromosome exome of a proband (III-2) from a large multigenerational family with NSXLID (Fig. 2A, Table 1, Supp. Table S1, family 7, see Materials and Methods and Hu et al. 2015), we identified a novel FTSJ1 variant c.76G>C, p.A26P (RefSeq NM_012280.2). Subsequent sequencing analysis of six other available family members showed that the c.76G>C; p.A26P allele segregates with ID (Fig. 2A, Supp. Fig. S2). The c.76G>C; p.A26P allele is not currently present in the Exome Variant Server, ExAC Browser, or SNP database from the UCSC genome browser. This variant was submitted to the Leiden Open Variation Database (http://www.lovd.nl/FTSJ1).

Figure 2.

The FTSJ1-p.A26P variant is associated with non-syndromic X-linked intellectual disability (NSXLID).

(A) Pedigree of family 7, with the FTSJ1-p.A26P allele. Filled square, affected male; circle with dot, known or obligate female carrier; open square, normal male; open circle, normal female. X-chromosome exome sequenced proband with the FTSJ1 NM_012280.2, c.76G>C, p.A26P variant is indicated by a red arrow. FTSJ1 genotype is indicated where DNA analysis was carried out. (+), c.76G>C; (−), wt. Nucleotide sequence is based on cDNA numbering.

(B) Amino acid sequence alignment of the N-terminal region of human FTSJ1 with known or predicted Trm7 proteins from diverse eukaryotes. Residue A26 is indicated by magenta arrow, and other residues analyzed in this study are indicated by black arrows.

(C) Predicted location of A26 residue of FTSJ1, based on the Escherichia coli RrmJ crystal structure. Representation of E. coli RrmJ (PDB 1EIZ), with catalytic triad residues in cyan, corresponding human FTSJ1 residues in round brackets, and corresponding S. cerevisiae residues in square brackets. Trp36 of RrmJ (corresponding to FTSJ1 p.A26) is magenta, and the predicted α-helix containing A26 (residues 33–46 of RrmJ) is dark gray.

Based on the fact that the FTSJ1-p.A26P allele was unique, segregated with ID in the pedigree, and is in a highly conserved region of the FTSJ1/Trm7 protein family (Fig. 2B), we predicted that this allele was deleterious to FTSJ1 protein function, thus causing ID in this family, consistent with previous studies linking loss of function FTSJ1 mutations and NSXLID (Freude, et al., 2004; Froyen, et al., 2007; Ramser, et al., 2004; Takano, et al., 2008). Indeed, the FTSJ1-p.A26P variant might also be expected to have impaired methyltransferase activity because p.A26 of FTSJ1 is only two residues from the predicted catalytic residue p.K28 in the same predicted α-helix, based on the structure of the FtsJ protein family member RrmJ (Fig. 2C) (Bugl, et al., 2000; Feder, et al., 2003; Pintard, et al., 2002).

The FTSJ1-p.A26P variant results in tRNAPhe lacking only Gm34

Consistent with a decrease in FTSJ1 activity, tRNAPhe from an LCL derived from the proband III-2 (Fig. 2A) with the FTSJ1-p.A26P allele had undetectable Gm (Table 2, Fig. 1B,C); however, this tRNAPhe had nearly normal Cm levels (0.63 moles/mole vs. 0.72 to 0.74 moles/mole in control LCLs with wild type FTSJ1), and o2yW37 levels (0.80 relative to 1.0 and 0.6 from two control LCLs, Table 2, Fig. 1D). The FTSJ1-p.A26P LCL was also defective for modification of tRNATrp with low, but detectable levels of Cm modification for the sample that was analyzed (0.15 vs 1.06 moles/mole, Supp. Table S4), but comparable levels of the other measured tRNATrp modifications.

S. cerevisiae Trm7-A26P forms Cm32, but not Gm34 on tRNAPhe in yeast cells

To further examine the defect of the FTSJ1-p.A26P variant, we determined if high level expression of FTSJ1-p.A26P could complement the growth defect of an S. cerevisiae trm7Δ mutant, by evaluating growth of a trm7Δ [CEN URA3 PTRM7-TRM7] strain containing a [2µ LEU2 PGAL-FTSJ1-p.A26P] plasmid, after plating on medium containing 5-FOA and galactose to select against the [CEN URA3 PTRM7-TRM7] plasmid. Consistent with our earlier results, expression of wild type FTSJ1 from a strong promoter on a high copy plasmid complemented the slow growth phenotype of the trm7Δ mutant (Guy and Phizicky, 2015); however, no complementation was observed upon expression of the FTSJ1-p.A26P variant, since growth on FOA was similar to that of the trm7Δ mutant bearing the vector or expressing the presumed catalytically dead variants FTSJ1-p.K28A or FTSJ1-p.K158A (Fig. 3A) (Feder, et al., 2003). We note, however, that levels of an affinity tagged FTSJ1-p.A26P-PT variant (for a description of the PT tag, see Supp. Methods) were reduced about 10-fold relative to those of FTSJ1-PT or the FTSJ1-p.K28A-PT variant (Supp. Fig. S3), suggesting that lack of complementation in yeast could be due, in part, to reduced protein levels.

Figure 3.

The S. cerevisiae Trm7-A26P variant is specifically defective for Gm34 modification of tRNAPhe.

(A) trm7-A26P suppresses the slow growth of S. cerevisiae trm7Δ mutants. Wild type and trm7Δ [CEN URA3 PTRM7-TRM7] strains with [LEU2] plasmids expressing FTSJ1 or TRM7 variants as indicated were grown overnight in S -Leu medium containing raffinose and galactose, diluted to OD600 of ~0.5 in H2O, and serially diluted 10-fold in H2O, and then 2 µL was spotted onto S medium containing raffinose, galactose, and 5-FOA, followed by incubation for 3 days at 30°C.

(B) An S. cerevisiae trm7Δ mutant expressing trm7-A26P from a low copy (CEN) plasmid efficiently forms Cm32, but not Gm34 on tRNAPhe. Quantification of nucleosides from tRNAPhe isolated from indicated yeast strains. (*), levels below threshold of detection.

(C) A CEN plasmid expressing trm7-A26P does not fully suppress the slow growth of S. cerevisiae trm7Δ trm732Δ mutants. Wild type, trm7Δ, trm7Δ trm732Δ, and trm7Δ trm734Δ strains with [CEN URA3 PTRM7-TRM7] and [LEU2] plasmids as indicated were grown overnight in SD-Leu, diluted, plated on SD-Leu medium containing 5-FOA, and incubated for 2 days at 30°C to select for loss of the URA3 plasmid (top panel), followed by growth analysis on YPD at the indicated temperatures (bottom panel).

However, we found that expression of S. cerevisiae trm7-A26P complements the growth defect of a trm7Δ mutant, with similar effects on tRNAPhe modification as in the human FTSJ1-p.A26P LCL. Thus, a [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-trm7-A26P] plasmid fully complemented a trm7Δ mutant, whereas no complementation was observed with plasmids expressing the predicted catalytic dead variants trm7-K28A or trm7-K164A (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, tRNAPhe from the trm7Δ [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-trm7-A26P] mutant had nearly normal levels of Cm32 (0.82 moles/mole vs. 1.00 in trm7Δ [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-TRM7] cells, Table 3, Fig. 3B) but barely measurable Gm34 (0.05 moles/mole vs. 0.81 in trm7Δ [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-TRM7] cells), almost exactly as observed for tRNAPhe from the FTSJ1-p.A26P human cell line. As expected of catalytic dead mutants, tRNAPhe from trm7Δ mutants expressing either trm7-K28A or trm7-K164A had no detectable Cm or Gm (Table 3, Fig. 3B); indeed, tRNAPhe from a trm7Δ strain overproducing trm7-K28A on a [2µ PGAL-trm7-K28A] plasmid still had no detectable Cm or Gm modifications. Consistent with the full modification of Cm32 and the partial modification of Gm34 of tRNAPhe by Trm7-A26P, introduction of a [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-trm7-A26P] plasmid fully suppressed the slow growth of a trm7Δ trm734Δ mutant, but only partially suppressed the slow growth of a trm7Δ trm732Δ mutant over a range of temperatures from 18°C to 37°C (Fig. 3C).

Table 3.

HPLC analysis of tRNAPhe nucleoside content from an S. cerevisiae trm7∆ strain expressing TRM7 variants

| modification moles expected |

medium | Cm 1 |

Gm 1 |

m1G 0 |

Ψ 2 |

m5C 2 |

m2G 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wild type [CENvec] | SD - Leu | 1.09 ± 0.23 | 0.85 ± 0.07 | <0.03 | 2.08 ± 0.10 | 1.77 ± 0.06 | 0.95 ± 0.09 |

| trm7Δ[CEN PTRM7-TRM7] | SD - Leu | 1.00 ± 0.12 | 0.81 ± 0.09 | <0.03 | 2.04 ± 0.04 | 1.75 ± 0.06 | 0.97 ± 0.06 |

| trm7Δ[CENvec] | SD - Leu | <0.03 | <0.03 | 1.01 ± 0.04 | 1.98 ± 0.10 | 1.78 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.06 |

| trm7Δ[CEN PTRM7-trm7-K28A] | SD - Leu | <0.03 | <0.03 | 1.02 ± 0.07 | 2.1 ± 0.11 | 1.82 ± 0.03 | 0.97 ± 0.08 |

| trm7Δ[CEN PTRM7-trm7- K164A] | SD - Leu | <0.03 | <0.03 | 1.04 ± 0.08 | 2.15 ± 0.08 | 1.83 ± 0.06 | 0.99 ± 0.09 |

| trm7Δ[CEN PTRM7-trm7-A26P] | SD - Leu | 0.82 ± 0.08 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.70 ± 0.12 | 2.01 ± 0.01 | 1.77 ± 0.04 | 0.97 ± 0.10 |

| trm7Δ[2µ PGAL-trm7-K28A] | S-Leu + raff gal | <0.03 | <0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 2.13 ± 0.07 | 1.64 ± 0.07 | 0.83 ± 0.05 |

| trm7Δ[CEN PTRM7-TRM7] | S-Leu + raff gal | 1.13 ± 0.06 | 0.88 ± 0.03 | <0.03 | 2.1 ± 0.08 | 1.83 ± 0.04 | 1.0 ± 0.01 |

| trm7Δ[CEN PTRM7-TRM7-MORF] | S-Leu + raff gal | 0.66 ± 0.13 | 0.50 ± 0.06 | 0.39 ± 0.06 | 2.06 ± 0.04 | 1.79 ± 0.03 | 0.96 ± 0.03 |

| trm7Δ[CEN PTRM7-trm7-A26P] | S-Leu + raff gal | 0.75 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 0.49± 0.07 | 2.11 ± 0.02 | 1.79 ± 0.02 | 0.99 ± 0.02 |

| trm7Δ[CEN PTRM7-trm7-A26P-MORF] | S-Leu + raff gal | 0.53 ± 0.10 | <0.03 | 0.75 ± 0.05 | 2.19 ± 0.08 | 1.79 ± 0.03 | 1.01 ± 0.01 |

| trm7Δ[2µ PGAL-TRM7] | S-Leu + raff gal | 0.98 ± 0.10 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | <0.03 | 2.18 ± 0.02 | 1.85 ± 0.06 | 0.98 ± 0.02 |

| trm7Δ[2µ PGAL-TRM7-PT] | S-Leu + raff gal | 0.89 ± 0.07 | 0.85 ± 0.04 | <0.03 | 2.12 ± 0.05 | 1.86 ± 0.04 | 0.93 ± 0.03 |

| trm7Δ[2µ PGAL-trm7-A26P] | S-Leu + raff gal | 0.93 ± 0.08 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 2.17 ± 0.03 | 1.85 ± 0.02 | 0.99 ± 0.02 |

| trm7Δ[2µ PGAL-trm7-A26P-PT] | S-Leu + raff gal | 0.97 ± 0.12 | <0.03 | 0.48 ± 0.08 | 2.16 ± 0.04 | 1.84 ± 0.02 | 1.01 ± 0.02 |

Mean and standard deviation based on three individual growths and RNA preparations.

To further characterize in vivo activity of the Trm7-A26P variant, we examined modifications of the other S. cerevisiae Trm7 substrates, tRNATrp and tRNALeu(UAA) (Pintard, et al., 2002). Both Cm32 and ncm5Um34 of tRNALeu(UAA) were virtually undetectable in the trm7Δ [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-trm7-A26P] mutant (Supp. Table S5). Similarly, both Cm32 and Cm34 of tRNATrp were severely reduced in the trm7Δ [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-trm7-A26P] mutant (0.09 vs. 1.40 moles/mole in wild type cells, Supp. Table S6), similar to the reduced Cm found on tRNATrp from FTSJ1-p.A26P LCLs (Supp. Table S4).

We note that the residual Cm found on tRNATrp in the trm7Δ [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-trm7-A26P] mutant was likely at C32, since similar Cm levels were found on tRNATrp from trm7Δ trm734Δ mutants, but no detectable Cm was found on tRNATrp from trm7Δ trm732Δ mutants (Supp. Table S6). This finding may suggest that the Trm7-A26P variant has retained some specificity for C32 modification, while losing specificity for N34 modification, regardless of base identity. As expected, the catalytic dead Trm7-K28A variant and the presumed catalytic dead Trm7-K164A variant lacked the ability to 2'-O-methylate tRNALeu(UAA) or tRNATrp (Supp. Tables S5 and S6). Our finding that the Trm7-A26P variant fully suppresses the growth defect of trm7Δ mutants, but only substantially modifies C32 of tRNAPhe (and not other tRNAs) is consistent with our previous findings that only Cm32 or Gm34 modification of tRNAPhe is required for healthy growth in S. cerevisiae (Guy, et al., 2012).

Overexpression of S. cerevisiae Trm7-A26P does not restore full Gm34 modification levels on tRNAPhe

Although expression of Trm7-A26P on a [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-trm7-A26P] plasmid fully complemented the growth defect of a trm7Δ mutant, expression levels of the corresponding C-terminally affinity-tagged Trm7-A26P-MORF variant (for a description of the MORF tag, see Materials and Methods) were reduced to ~1/3 the levels observed from corresponding strains expressing wild type Trm7-MORF or the Trm7-K28A-MORF variant (Supp. Fig. S4). Thus, it was possible that the selective loss of Gm34 on tRNAPhe in the trm7Δ [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-trm7-A26P] mutant was due to reduced Trm7-A26P. Alternatively, it might be due to reduced interaction of Trm7-A26P with Trm734, since Trm7 forms a distinct complex with Trm734, and both proteins are required for Nm34 formation in S. cerevisiae (Guy, et al., 2012).

To test if there was a reduced interaction between Trm7-A26P and Trm734, we transformed CEN plasmids expressing TRM7-MORF or trm7-A26P-MORF into TRM732-9myc or TRM734-9myc yeast strains, and then purified the Trm7 using the tag. Both Trm732-9myc and Trm734-9myc co-purified with Trm7-MORF and with Trm7-A26P-MORF with comparable efficiency, after taking into account the reduced expression of Trm7-A26P (Fig. 4A,B).

Figure 4.

The defect in S. cerevisiae Trm7-A26P function is not due to reduced expression or reduced Trm734 binding.

(A) Trm7-A26P-MORF expressed from a CEN plasmid efficiently forms a complex with chromosomally expressed Trm732-9myc. Crude extracts were prepared from the indicated strains grown in SD-Leu medium, and proteins were purified with IgG-Sepharose beads (which binds the ZZ domain of the MORF tag), followed by treatment with 3C protease, as described in Materials and Methods, and then samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analysis as indicated.

(B) Trm7-A26P-MORF expressed from a CEN plasmid forms a complex with chromosomally expressed Trm734-9myc. Samples were analyzed as in panel A.

(C) Trm7-A26P-PT expressed from a high copy (2µ) plasmid forms more Trm7-A26P:Trm734-9myc complex than the corresponding Trm7:Trm734-9myc complex in wild type cells. Indicated samples grown in S-Leu medium containing raffinose and galactose were analyzed as in panel A.

(D) Overexpressed TRM7-A26P does not fully suppress the slow growth of S. cerevisiae trm7Δ trm732Δ mutants. Wild type and trm7Δ trm732Δ strains with plasmids as indicated were grown overnight in S -Leu medium containing raffinose and galactose as in Figure 3A, and spotted to the indicated media.

To further probe the selective loss of Gm34 on tRNAPhe in the trm7Δ strain expressing trm7-A26P, we overexpressed Trm7-A26P and examined the interaction with Trm734 and Gm levels of tRNAPhe. Immunoblot analysis against the ZZ domain of protein A demonstrated that expression of Trm7-A26P-PT (the PT tag has identical components as the MORF tag, see Supp. Methods) from a 2µ PGALplasmid ([2µ URA3 PGAL-trm7-A26P-PT]) resulted in more than a 125-fold increase in Trm7-A26P levels, compared to wild type Trm7-MORF expressed from a [CEN URA3 PTRM7-TRM7-MORF] plasmid (Fig. 4C). Furthermore, purification of overexpressed Trm7-A26P-PT resulted in pulldown of ~10-fold more Trm734-9myc than was pulled down during purification of Trm7-MORF expressed from the [CEN URA3 PTRM7-TRM7-MORF] plasmid. However, despite the >125-fold overexpression and the ~10-fold increase in Trm734 pull down, Gm34 formation on tRNAPhe was not fully restored by overexpression of either tagged Trm7-A26P from the [2µ LEU2 PGAL-TRM7-A26P-PT] plasmid or untagged Trm7-A26P from the otherwise identical [2µ LEU2 PGAL-TRM7-A26P] plasmid (Table 3). Indeed, under these conditions, overexpression of untagged Trm7-A26P in the trm7Δ strain resulted in only 0.26 moles/mole Gm on tRNAPhe. Consistent with this finding, overexpression of trm7-A26P also failed to fully suppress the growth defect of a trm7Δ trm732Δ mutant (Fig. 4D).

We note that the C-terminal tag of Trm7-PT or Trm7-MORF appears to interfere with Gm formation, since Gm modification of tRNAPhe was reduced from 0.88 to 0.50 moles/mole in a trm7Δ [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-TRM7-MORF] strain relative to a trm7Δ [CEN PTRM7-LEU2 TRM7] strain (Table 3), and similar results were observed when TRM7 had a C-terminal c-myc tag (data not shown). This loss of Gm modification is even more extreme in the corresponding strains expressing Trm7-A26P-MORF or Trm7-A26P-PT. Nonetheless, we conclude that the loss of Gm34 modification activity in the Trm7-A26P variant is not due to a Trm734 binding defect, since overexpression of Trm7-A26P-PT results in more pulldown of Trm734 than occurs with wild type Trm7-MORF expressed from a CEN plasmid, whereas overexpression of even untagged Trm7-A26P (presumably resulting in the same or more Trm7 than with tagged Trm7) does not fully rescue Gm34 modification of tRNAPhe (Table 3).

Overexpression of untagged Trm7-A26P also appeared to result in a modest but limited increase in Cm levels on tRNATrp purified from trm7Δ mutants (from 0.13 to 0.31 moles/mole, Supp. Table S7), and modest increases in Cm and ncm5Um levels in tRNALeu(UAA) (Supp. Table S8). Thus, all modification defects associated with normal expression of Trm7-A26P appear to persist even when Trm7-A26P is massively overproduced.

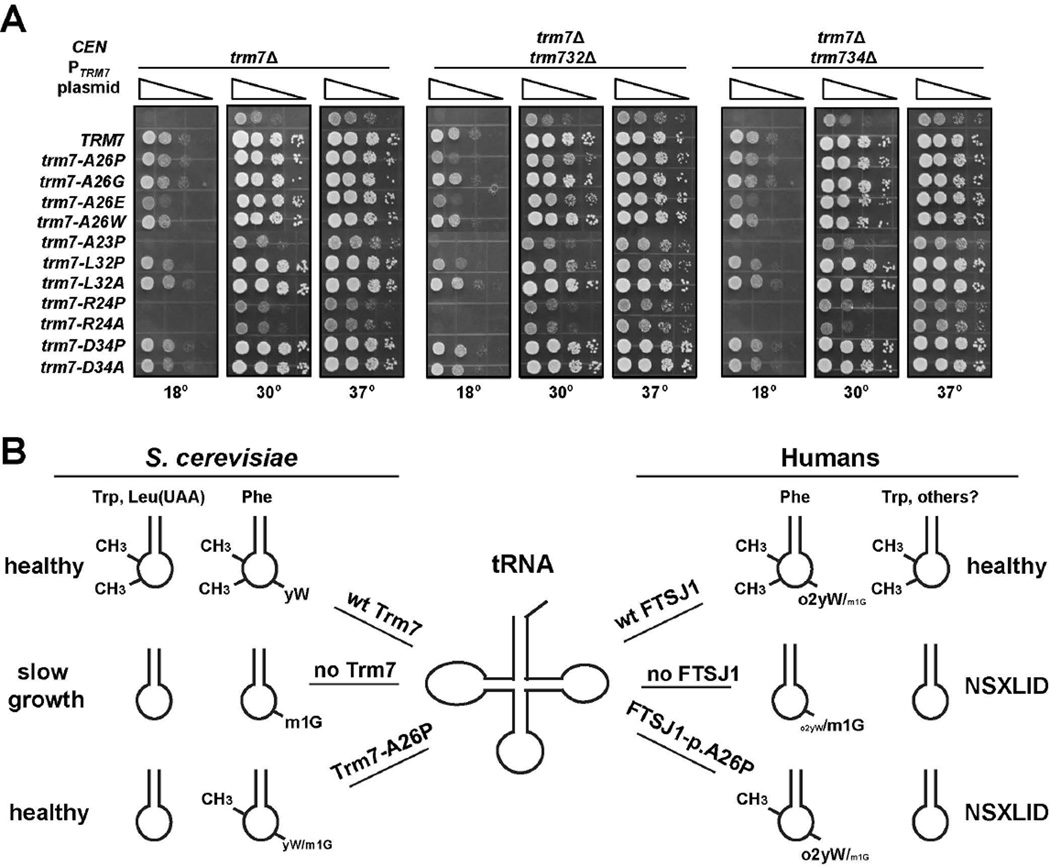

Other mutations in the predicted α-helix bearing A26 of Trm7 result in tRNAPhe specifically lacking Gm34

We investigated the roles of other Trm7 residues in the region near residue A26 because of its proximity to the catalytic residue K28 and because of the intriguing observation that Trm7-A26P efficiently forms Cm32, but not Gm34, on tRNAPhe. We constructed [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-TRM7] plasmids expressing Trm7 variants bearing other amino acid substitutions at A26, and substitutions in the predicted α-helix bearing A26 (which encompasses residues 23–36, based on E. coli RrmJ (Bugl, et al., 2000)), and then tested their ability to suppress the growth defects of trm7Δ, trm7Δ trm732Δ, and trm7Δ trm734Δ mutants.

We found that expression of the trm7-A26W or trm7-A26G variant resulted in complete complementation of the growth defect in all three strain backgrounds, whereas expression of trm7-A26E resulted in a distinct growth defect only in the trm7Δ trm732Δ strain at 30°C (Fig. 5A), similar to the phenotype resulting from the trm7-A26P variant, although there was also a minor growth defect in the trm7Δ and trm7Δ trm734Δ backgrounds that was more obvious at 18°C. Consistent with this result, we found that tRNAPhe from the trm7Δ [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-trm7-A26E] strain had undetectable Gm levels and about 50% of the normal Cm levels (0.54 vs 1.00 moles/mole), whereas Cm and Gm of tRNAPhe were at near normal levels in the trm7Δ [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-trm7A26W] strain (1.03 and 0.54 moles/mole respectively, compared to 1.0 and 0.81 moles/mole in wild type; Supp. Table S9).

Figure 5.

Genetic analysis of Trm7 variant function in S. cerevisiae.

(A) Growth assay for Trm7 variant function. τρµ7Δ, trm7Δ trm732Δ, and trm7Δ trm734Δ strains expressing CEN trm7 variants as indicated were grown overnight in SD-Leu, diluted, spotted on YPD medium, and incubated at the indicated temperatures.

(B) Schematic of phenotypes associated with loss of FTSJ1/Trm7 activity in humans and yeast. Relative size of yW/o2yW/m1G corresponds to levels of these modifications on residue 37 of tRNAPhe.

Similar to our observations with the trm7-A26P and trm7-A26E variants, we found that expression of a trm7-L32P variant resulted in a growth defect specifically in the trm7Δ trm732Δ strain, and not in the trm7Δ or trm7Δ trm734Δ strains (Fig. 5A), and that tRNAPhe from the trm7Δ [CEN LEU2 PTRM7-trm7-L32P] strain had barely detectable Gm (0.03 moles/mole) but nearly normal levels of Cm (0.90 moles/mole) (Supp. Table S9). By contrast, expression of the trm7-L32A variant complemented the growth defect of all three strains and yielded normal tRNAPhe modifications (Fig. 5A; Supp. Table S9), while expression of trm7-A23P, trm7-R24A, or trm7-R24P variants resulted in no complementation in any strain background, suggesting lack of function for these variants.

Thus, these results demonstrate that Trm7 variants with other mutations at A26 or elsewhere in the helix specifically lose the ability to form Gm34 on tRNAPhe while retaining Cm32 modification ability.

Discussion

In this report we have provided strong evidence that human FTSJ1 is required for Cm32 and Gm34 modification of tRNAPhe, since these tRNAPhe modifications were undetectable, or drastically reduced, in each of three LCLs derived from NSXLID patients with two distinct FTSJ1 loss of function mutations, whereas tRNAPhe from each of two control cell lines derived from healthy individuals with wild type FTSJ1 had essentially normal Cm and Gm levels. Since we also observed parallel selective loss of Gm in tRNAPhe from the FTSJ1-p.A26P LCLs and from the S. cerevisiae trm7-A26P mutant (Fig. 5B), and since expression of FTSJ1 complements the growth defect of an S. cerevisiae trm7Δ mutant by forming Cm32 on tRNAPhe (Guy and Phizicky, 2015), we conclude that FTSJ1 catalyzes formation of Cm and Gm on tRNAPhe in human cells. Furthermore, since FTSJ1 mutant alleles segregate with NSXLID in each of the previously reported families from which the LCLs were derived (Freude, et al., 2004; Froyen, et al., 2007), in the new family with the p.A26P variant reported here, as well as in four other reported families (Freude, et al., 2004; Ramser, et al., 2004; Takano, et al., 2008) and likely in an additional family (Hu, et al., 2015), we conclude further that defective 2'-O-methylation of N32 and N34 of the anticodon loop of substrate tRNAs is a major contributing factor in FTSJ1-associated NSXLID.

FTSJ1 mutations might contribute to NSXLID through lack of modification of any FTSJ1 tRNA substrate. Indeed, we provided evidence that FTSJ1 modifies tRNATrp in LCLs, and Cm modification of this tRNA was severely reduced in FTSJ1-p.A26P LCLs. Moreover, it is possible that FTSJ1 modifies any of the four other documented human tRNA species with Nm32 and/or Nm34 (Machnicka, et al., 2013), or any of the numerous uncharacterized tRNAs, and hypomodification of any of these tRNAs could contribute to ID. However, we speculate that defective 2'-O-methylation of tRNAPhe may play a major role in ID, for two reasons. First, reduced function of tRNAPhe is the major cause of the slow growth defect of S. cerevisiae and S. pombe trm7Δ mutants (Guy and Phizicky, 2015; Guy, et al., 2012). Second, the tRNAPhe anticodon loop 2'-O-methylations are very highly conserved, since each of the 17 eukaryotic tRNAPhe species that have been characterized has Cm32, and 16 of the 17 also have Gm34 (Machnicka, et al., 2013). If lack of tRNAPhe modification by FTSJ1 is a major contributor to NSXLID, then it would follow that the defective tRNAPhe would primarily be due to lack of Gm34, because levels of both Cm32 and o2yW37 are normal in the FTSJ1-p.A26P LCL. This importance of Gm34 of tRNAPhe would be consistent with the finding in S. pombe that Gm34 of tRNAPhe is much more important for function than Cm32, as measured by growth phenotypes of mutants (Guy and Phizicky, 2015). We note that NSXLID patients with the FTSJ1-p.A26P mutation appear to have ID comparable to that of other FTSJ1-associated NSXLID patients (Supp. Table S1), although there have not been any direct, objective comparisons of the extent of ID for each of the NSXLID patients.

These results also underscore the conservation of the intricate circuitry for anticodon loop modification of tRNAPhe, as tRNAPhe from LCLs of patients with splice site and null alleles of FTSJ1 had significantly reduced levels of o2yW37, compared to control LCLs, accompanied by increased levels of the o2yW precursor m1G. This result suggests that the o2yW37 modification may be dependent on Cm32 and Gm34 modification, as is the yW37 modification in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe (Guy and Phizicky, 2015; Guy, et al., 2012). However, unlike in these yeast species, lack of FTSJ1 in human LCLs did not completely abrogate o2yW modification of tRNAPhe, lack of Gm34 did not appear to affect o2yW37 levels, and control LCLs had variable levels of o2yW, accompanied by correspondingly variable m1G levels. The apparent dependence of o2yW37 on Cm32 and Gm34 is consistent with previous observations that tRNAPhe from neuroblastoma cells and a fraction of tRNAPhe from Ehrlich ascites cell lines lack Cm, Gm, and o2yW (Kuchino, et al., 1982), although it is not clear why tRNAPhe was affected in these cell lines.

It is intriguing that both human FTSJ1-p.A26P and yeast Trm7-A26P are specifically defective in Gm34 modification of tRNAPhe, while retaining normal levels of Cm32 modification. Since our data indicates that overproduction of Trm7 by more than 125-fold can rescue the minor defect in Trm734 binding but not the Gm modification defect, this result suggests that the Trm7-A26P defect is due to some specific aspect of substrate recognition or catalysis for Gm34 modification. This interpretation is consistent with the location of residue 26 near the catalytic residue K28 (Feder, et al., 2003; Pintard, et al., 2002). Alternatively, G34 of tRNAPhe may simply be more difficult to modify than C32, and the p.A26P mutation might cause a general loss in methylation activity. This interpretation is consistent with the observation that tRNAPhe from FTSJ1-ss LCLs have distinct but low levels of Cm and no detectable Gm, perhaps suggesting a low level of correct mRNA splicing (Freude, et al., 2004). Moreover, Cm32 of tRNAPhe appears to be the most efficient Trm7 modification target in yeast since overproduction of the Trm7-A26P variant only results in partial modification of C32 and N34 of tRNATrp and tRNALeu(UAA), whereas C32 of tRNAPhe is normally modified even when Trm7-A26P is expressed at normal levels. The observation that yeast trm7Δ mutants expressing Trm7-A26E or Trm7-L32P at normal levels also selectively modify C32, but not G34, of tRNAPhe emphasizes the sensitivity of the crucial Gm34 modification to perturbations in this helix, but leaves unresolved the mechanism by which this occurs.

Since FTSJ1-associated NSXLID patients have no consistent dysmorphic, metabolic or neuromuscular manifestations of the condition other than intellectual disability, it would follow that the functional levels of substrate tRNAs are insufficient for brain development and/or cognitive function, but are sufficient in other tissues and other aspects of development. Although little is known about the differential expression of the 450 tRNA genes in the human genome, comprising ~270 isodecoders (which share an anticodon but have a different tRNA body) (Chan and Lowe, 2009; Goodenbour and Pan, 2006), there is evidence that an isodecoder can be specifically expressed in the central nervous system (Ishimura, et al., 2014). A role for FTSJ1 in neurological development is consistent with the observation that expression of FTSJ1 mRNA in the fetus is highest in the brain compared to other tissues tested (Freude, et al., 2004).

The linkage between tRNA modifications and NSXLID reported here is part of an emerging theme linking tRNA modifications and neurological function. Previous studies have directly linked defective m5C modification to a Dubowitz-like syndrome (Blanco, et al., 2014; Martinez, et al., 2012), and defective cm5U modification to FD (Anderson, et al., 2001; Karlsborn, et al., 2014), and lesions in four other predicted or likely tRNA modification genes have been linked to neurological function. Thus, lesions in the TRMT10A gene, a homolog of yeast TRM10 (Jackman, et al., 2003), are linked to short stature, microcephaly, and defects in glucose homeostasis and diabetes, and the purified protein corresponding to a missense allele lacks tRNA m1G9 methyltransferase activity (Gillis, et al., 2014; Igoillo-Esteve, et al., 2013). Additionally, a missense allele of human ADAT3, the likely homolog of yeast TAD3, required for deamination of A34 to I34 (Gerber and Keller, 1999), is linked to strabismus and ARID (Alazami, et al., 2013); a frameshift mutation in human TRMT1, the homolog of yeast TRM1, required for m2,2G26 activity (Liu and Straby, 2000), is linked to ARID (Najmabadi, et al., 2011); and two distinct missense alleles of human ELP2, a member of the ELP complex (Hawkes, et al., 2002; Huang, et al., 2005), are linked to ARID (Najmabadi, et al., 2011). In addition, allelic variants in the human ELP3 gene have been linked by genome-wide association studies to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Elp3 mutants were identified in an accompanying screen for defective neuronal function in Drosophila (Simpson, et al., 2009). We note also that tRNA mutations leading to defects in taurine modifications are implicated in MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes) and MERFF (myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibers)(Suzuki, et al., 2002; Yasukawa, et al., 2000a; Yasukawa, et al., 2000b), while a TRIT1 mutation resulting in reduced i6A modification is linked to myoclonic epilepsy associated with encephalopathy (Yarham, et al., 2014).

Since lack of modifications is often overcome by increased dosage of one or more of the unmodified tRNAs (Esberg, et al., 2006; Fernandez-Vazquez, et al., 2013; Guy, et al., 2012; Han, et al., 2015; Phizicky and Alfonzo, 2010), the numerous links between tRNA modifications and neurological defects suggest that the available pool of functional tRNAs may somehow be limited during development and function of the central nervous system, presumably leading to defects in translation or its regulation (Begley, et al., 2007; Chan, et al., 2012). The specific mechanisms by which defects in tRNA biology impact neurological function remain to be determined.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the family studied for their participation, R. Carroll and R. Alhamra for laboratory assistance, and E. Grayhack for helpful discussions and insights.

Grant Sponsors: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM052347 to E.M.P. and by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia grants APP628952, APP1041920, and APP1008077 to J.G.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abbasi-Moheb L, Mertel S, Gonsior M, Nouri-Vahid L, Kahrizi K, Cirak S, Wieczorek D, Motazacker MM, Esmaeeli-Nieh S, Cremer K, et al. Mutations in NSUN2 cause autosomal-recessive intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(5):847–855. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agris PF, Vendeix FA, Graham WD. tRNA's wobble decoding of the genome: 40 years of modification. J Mol Biol. 2007;366(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alazami AM, Hijazi H, Al-Dosari MS, Shaheen R, Hashem A, Aldahmesh MA, Mohamed JY, Kentab A, Salih MA, Awaji A, et al. Mutation in ADAT3, encoding adenosine deaminase acting on transfer RNA, causes intellectual disability and strabismus. J Med Genet. 2013;50(7):425–430. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov A, Chernyakov I, Gu W, Hiley SL, Hughes TR, Grayhack EJ, Phizicky EM. Rapid tRNA decay can result from lack of nonessential modifications. Mol Cell. 2006;21(1):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SL, Coli R, Daly IW, Kichula EA, Rork MJ, Volpi SA, Ekstein J, Rubin BY. Familial dysautonomia is caused by mutations of the IKAP gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68(3):753–758. doi: 10.1086/318808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley U, Dyavaiah M, Patil A, Rooney JP, DiRenzo D, Young CM, Conklin DS, Zitomer RS, Begley TJ. Trm9-catalyzed tRNA modifications link translation to the DNA damage response. Mol Cell. 2007;28(5):860–870. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekaert M, Rousset JP. An extended signal involved in eukaryotic-1 frameshifting operates through modification of the E site tRNA. Mol Cell. 2005;17(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco S, Dietmann S, Flores JV, Hussain S, Kutter C, Humphreys P, Lukk M, Lombard P, Treps L, Popis M, et al. Aberrant methylation of tRNAs links cellular stress to neuro-developmental disorders. EMBO J. 2014;33(18):2020–2039. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco S, Kurowski A, Nichols J, Watt FM, Benitah SA, Frye M. The RNA-methyltransferase Misu (NSun2) poises epidermal stem cells to differentiate. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(12):e1002403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezicha B, Schmidt M, Makalowska I, Jarmolowski A, Pienkowska J, Szweykowska-Kulinska Z. Identification of human tRNA:m5C methyltransferase catalysing intron-dependent m5C formation in the first position of the anticodon of the pre-tRNA Leu (CAA) Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(20):6034–6043. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugl H, Fauman EB, Staker BL, Zheng F, Kushner SR, Saper MA, Bardwell JC, Jakob U. RNA methylation under heat shock control. Mol Cell. 2000;6(2):349–360. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan CT, Pang YL, Deng W, Babu IR, Dyavaiah M, Begley TJ, Dedon PC. Reprogramming of tRNA modifications controls the oxidative stress response by codon-biased translation of proteins. Nat Commun. 2012;3:937. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan PP, Lowe TM. GtRNAdb: a database of transfer RNA genes detected in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D93–D97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn787. (Database issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyakov I, Whipple JM, Kotelawala L, Grayhack EJ, Phizicky EM. Degradation of several hypomodified mature tRNA species in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is mediated by Met22 and the 5'-3' exonucleases Rat1 and Xrn1. Genes Dev. 2008;22(10):1369–1380. doi: 10.1101/gad.1654308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuajungco MP, Leyne M, Mull J, Gill SP, Lu W, Zagzag D, Axelrod FB, Maayan C, Gusella JF, Slaugenhaupt SA. Tissue-specific reduction in splicing efficiency of IKBKAP due to the major mutation associated with familial dysautonomia. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(3):749–758. doi: 10.1086/368263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Crecy-Lagard V, Marck C, Grosjean H. Decoding in Candidatus Riesia pediculicola, close to a minimal tRNA modification set? Trends Cell Mol Biol. 2012;7:11–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Edelmann L, Bajwa AM, Kornreich R, Desnick RJ. Familial dysautonomia: detection of the IKBKAP IVS20(+6T -->C) and R696P mutations and frequencies among Ashkenazi Jews. Am J Med Genet. 2002;110(3):253–257. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esberg A, Huang B, Johansson MJ, Bystrom AS. Elevated levels of two tRNA species bypass the requirement for elongator complex in transcription and exocytosis. Mol Cell. 2006;24(1):139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahiminiya S, Almuriekhi M, Nawaz Z, Staffa A, Lepage P, Ali R, Hashim L, Schwartzentruber J, Abu Khadija K, Zaineddin S, et al. Whole exome sequencing unravels disease-causing genes in consanguineous families in Qatar. Clin Genet. 2014;86(2):134–141. doi: 10.1111/cge.12280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder M, Pas J, Wyrwicz LS, Bujnicki JM. Molecular phylogenetics of the RrmJ/fibrillarin superfamily of ribose 2'-O-methyltransferases. Gene. 2003;302(1–2):129–138. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Vazquez J, Vargas-Perez I, Sanso M, Buhne K, Carmona M, Paulo E, Hermand D, Rodriguez-Gabriel M, Ayte J, Leidel S, et al. Modification of tRNA(Lys) UUU by elongator is essential for efficient translation of stress mRNAs. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(7):e1003647. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier M, Labouesse J, Dirheimer G, Fix C, Keith G. Primary structure of bovine liver tRNATrp. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;521(1):198–208. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(78)90262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freude K, Hoffmann K, Jensen LR, Delatycki MB, des Portes V, Moser B, Hamel B, van Bokhoven H, Moraine C, Fryns JP, et al. Mutations in the FTSJ1 gene coding for a novel S-adenosylmethionine-binding protein cause nonsyndromic X-linked mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(2):305–309. doi: 10.1086/422507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froyen G, Bauters M, Boyle J, Van Esch H, Govaerts K, van Bokhoven H, Ropers HH, Moraine C, Chelly J, Fryns JP, et al. Loss of SLC38A5 and FTSJ1 at Xp11.23 in three brothers with non-syndromic mental retardation due to a microdeletion in an unstable genomic region. Hum Genet. 2007;121(5):539–547. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0343-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber AP, Keller W. An adenosine deaminase that generates inosine at the wobble position of tRNAs. Science. 1999;286(5442):1146–1149. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis D, Krishnamohan A, Yaacov B, Shaag A, Jackman JE, Elpeleg O. TRMT10A dysfunction is associated with abnormalities in glucose homeostasis, short stature and microcephaly. J Med Genet. 2014;51(9):581–586. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenbour JM, Pan T. Diversity of tRNA genes in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(21):6137–6146. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy MP, Phizicky EM. Conservation of an intricate circuit for crucial modifications of the tRNAPhe anticodon loop in eukaryotes. RNA. 2015;21(1):61–74. doi: 10.1261/rna.047639.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy MP, Podyma BM, Preston MA, Shaheen HH, Krivos KL, Limbach PA, Hopper AK, Phizicky EM. Yeast Trm7 interacts with distinct proteins for critical modifications of the tRNAPhe anticodon loop. RNA. 2012;18(10):1921–1933. doi: 10.1261/rna.035287.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall KB, Sampson JR, Uhlenbeck OC, Redfield AG. Structure of an unmodified tRNA molecule. Biochemistry. 1989;28(14):5794–5801. doi: 10.1021/bi00440a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L, Kon Y, Phizicky EM. Functional importance of Psi38 and Psi39 in distinct tRNAs, amplified for tRNAGln(UUG) by unexpected temperature sensitivity of the s2U modification in yeast. RNA. 2015;21(2):188–201. doi: 10.1261/rna.048173.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes NA, Otero G, Winkler GS, Marshall N, Dahmus ME, Krappmann D, Scheidereit C, Thomas CL, Schiavo G, Erdjument-Bromage H, et al. Purification and characterization of the human elongator complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(4):3047–3052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm M, Giege R, Florentz C. A Watson-Crick base-pair-disrupting methyl group (m1A9) is sufficient for cloverleaf folding of human mitochondrial tRNALys. Biochemistry. 1999;38(40):13338–13346. doi: 10.1021/bi991061g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper AK. Transfer RNA post-transcriptional processing, turnover, and subcellular dynamics in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2013;194(1):43–67. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.147470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Haas SA, Chelly J, Van Esch H, Raynaud M, de Brouwer AP, Weinert S, Froyen G, Frints SG, Laumonnier F, et al. X-exome sequencing of 405 unresolved families identifies seven novel intellectual disability genes. Mol Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Johansson MJ, Bystrom AS. An early step in wobble uridine tRNA modification requires the Elongator complex. RNA. 2005;11(4):424–436. doi: 10.1261/rna.7247705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igoillo-Esteve M, Genin A, Lambert N, Desir J, Pirson I, Abdulkarim B, Simonis N, Drielsma A, Marselli L, Marchetti P, et al. tRNA methyltransferase homolog gene TRMT10A mutation in young onset diabetes and primary microcephaly in humans. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(10):e1003888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimura R, Nagy G, Dotu I, Zhou H, Yang XL, Schimmel P, Senju S, Nishimura Y, Chuang JH, Ackerman SL. Ribosome stalling induced by mutation of a CNS-specific tRNA causes neurodegeneration. Science. 2014;345(6195):455–459. doi: 10.1126/science.1249749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman JE, Montange RK, Malik HS, Phizicky EM. Identification of the yeast gene encoding the tRNA m1G methyltransferase responsible for modification at position 9. RNA. 2003;9(5):574–585. doi: 10.1261/rna.5070303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadaba S, Krueger A, Trice T, Krecic AM, Hinnebusch AG, Anderson J. Nuclear surveillance and degradation of hypomodified initiator tRNAMet in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 2004;18(11):1227–1240. doi: 10.1101/gad.1183804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadaba S, Wang X, Anderson JT. Nuclear RNA surveillance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Trf4p-dependent polyadenylation of nascent hypomethylated tRNA and an aberrant form of 5S rRNA. RNA. 2006;12(3):508–521. doi: 10.1261/rna.2305406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsborn T, Tukenmez H, Chen C, Bystrom AS. Familial dysautonomia (FD) patients have reduced levels of the modified wobble nucleoside mcm5s2U in tRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;454(3):441–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MA, Rafiq MA, Noor A, Hussain S, Flores JV, Rupp V, Vincent AK, Malli R, Ali G, Khan FS, et al. Mutation in NSUN2, which encodes an RNA methyltransferase, causes autosomal-recessive intellectual disability. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(5):856–863. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchino Y, Borek E, Grunberger D, Mushinski JF, Nishimura S. Changes of post-transcriptional modification of wye base in tumor-specific tRNAPhe. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10(20):6421–6432. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.20.6421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCava J, Houseley J, Saveanu C, Petfalski E, Thompson E, Jacquier A, Tollervey D. RNA degradation by the exosome is promoted by a nuclear polyadenylation complex. Cell. 2005;121(5):713–724. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Straby KB. The human tRNA(m(2)(2)G(26))dimethyltransferase: functional expression and characterization of a cloned hTRM1 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(18):3445–3451. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.18.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machnicka MA, Milanowska K, Osman Oglou O, Purta E, Kurkowska M, Olchowik A, Januszewski W, Kalinowski S, Dunin-Horkawicz S, Rother KM, et al. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways--2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D262–D267. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1007. (Database issue) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FJ, Lee JH, Lee JE, Blanco S, Nickerson E, Gabriel S, Frye M, Al-Gazali L, Gleeson JG. Whole exome sequencing identifies a splicing mutation in NSUN2 as a cause of a Dubowitz-like syndrome. J Med Genet. 2012;49(6):380–385. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motorin Y, Grosjean H. Multisite-specific tRNA:m5C-methyltransferase (Trm4) in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: identification of the gene and substrate specificity of the enzyme. RNA. 1999;5(8):1105–1118. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299982201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu T, Nishikawa K, Nemoto F, Kuchino Y, Nishimura S, Miyazawa T, Yokoyama S. Codon and amino-acid specificities of a transfer RNA are both converted by a single post-transcriptional modification. Nature. 1988;336(6195):179–181. doi: 10.1038/336179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy FVt, Ramakrishnan V, Malkiewicz A, Agris PF. The role of modifications in codon discrimination by tRNA(Lys)UUU. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11(12):1186–1191. doi: 10.1038/nsmb861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najmabadi H, Hu H, Garshasbi M, Zemojtel T, Abedini SS, Chen W, Hosseini M, Behjati F, Haas S, Jamali P, et al. Deep sequencing reveals 50 novel genes for recessive cognitive disorders. Nature. 2011;478(7367):57–63. doi: 10.1038/nature10423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noma A, Kirino Y, Ikeuchi Y, Suzuki T. Biosynthesis of wybutosine, a hyper-modified nucleoside in eukaryotic phenylalanine tRNA. EMBO J. 2006;25(10):2142–2154. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phizicky EM, Alfonzo JD. Do all modifications benefit all tRNAs? FEBS Lett. 2010;584(2):265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pintard L, Lecointe F, Bujnicki JM, Bonnerot C, Grosjean H, Lapeyre B. Trm7p catalyses the formation of two 2'-O-methylriboses in yeast tRNA anticodon loop. EMBO J. 2002;21(7):1811–1820. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putz J, Florentz C, Benseler F, Giege R. A single methyl group prevents the mischarging of a tRNA. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1(9):580–582. doi: 10.1038/nsb0994-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quartley E, Alexandrov A, Mikucki M, Buckner FS, Hol WG, DeTitta GT, Phizicky EM, Grayhack EJ. Heterologous expression of L. major proteins in S. cerevisiae: a test of solubility, purity, and gene recoding. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2009;10(3):233–247. doi: 10.1007/s10969-009-9068-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramser J, Winnepenninckx B, Lenski C, Errijgers V, Platzer M, Schwartz CE, Meindl A, Kooy RF. A splice site mutation in the methyltransferase gene FTSJ1 in Xp11.23 is associated with non-syndromic mental retardation in a large Belgian family (MRX9) J Med Genet. 2004;41(9):679–683. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.019000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C, Anderson JT, Tollervey D. The exosome subunit Rrp44 plays a direct role in RNA substrate recognition. Mol Cell. 2007;27(2):324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson CL, Lemmens R, Miskiewicz K, Broom WJ, Hansen VK, van Vught PW, Landers JE, Sapp P, Van Den Bosch L, Knight J, et al. Variants of the elongator protein 3 (ELP3) gene are associated with motor neuron degeneration. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(3):472–481. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaugenhaupt SA, Blumenfeld A, Gill SP, Leyne M, Mull J, Cuajungco MP, Liebert CB, Chadwick B, Idelson M, Reznik L, et al. Tissue-specific expression of a splicing mutation in the IKBKAP gene causes familial dysautonomia. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68(3):598–605. doi: 10.1086/318810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Wada T, Saigo K, Watanabe K. Taurine as a constituent of mitochondrial tRNAs: new insights into the functions of taurine and human mitochondrial diseases. EMBO J. 2002;21(23):6581–6589. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano K, Nakagawa E, Inoue K, Kamada F, Kure S, Goto Y. A loss-of-function mutation in the FTSJ1 gene causes nonsyndromic X-linked mental retardation in a Japanese family. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B(4):479–484. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuorto F, Liebers R, Musch T, Schaefer M, Hofmann S, Kellner S, Frye M, Helm M, Stoecklin G, Lyko F. RNA cytosine methylation by Dnmt2 and NSun2 promotes tRNA stability and protein synthesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(9):900–905. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbonavicius J, Qian Q, Durand JM, Hagervall TG, Bjork GR. Improvement of reading frame maintenance is a common function for several tRNA modifications. EMBO J. 2001;20(17):4863–4873. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanacova S, Wolf J, Martin G, Blank D, Dettwiler S, Friedlein A, Langen H, Keith G, Keller W. A new yeast poly(A) polymerase complex involved in RNA quality control. PLoS Biol. 2005;3(6):e189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waas WF, Druzina Z, Hanan M, Schimmel P. Role of a tRNA base modification and its precursors in frameshifting in eukaryotes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(36):26026–26034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703391200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whipple JM, Lane EA, Chernyakov I, D'Silva S, Phizicky EM. The yeast rapid tRNA decay pathway primarily monitors the structural integrity of the acceptor and T-stems of mature tRNA. Genes Dev. 2011;25(11):1173–1184. doi: 10.1101/gad.2050711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarham JW, Lamichhane TN, Pyle A, Mattijssen S, Baruffini E, Bruni F, Donnini C, Vassilev A, He L, Blakely EL, et al. Defective i6A37 Modification of Mitochondrial and Cytosolic tRNAs Results from Pathogenic Mutations in TRIT1 and Its Substrate tRNA. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(6):e1004424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasukawa T, Suzuki T, Ishii N, Ueda T, Ohta S, Watanabe K. Defect in modification at the anticodon wobble nucleotide of mitochondrial tRNA(Lys) with the MERRF encephalomyopathy pathogenic mutation. FEBS Lett. 2000a;467(2–3):175–178. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasukawa T, Suzuki T, Ueda T, Ohta S, Watanabe K. Modification defect at anticodon wobble nucleotide of mitochondrial tRNAs(Leu)(UUR) with pathogenic mutations of mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes. J Biol Chem. 2000b;275(6):4251–4257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue D, Kintanar A, Horowitz J. Nucleoside modifications stabilize Mg2+ binding in Escherichia coli tRNA(Val): an imino proton NMR investigation. Biochemistry. 1994;33(30):8905–8911. doi: 10.1021/bi00196a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeharia A, Shaag A, Pappo O, Mager-Heckel AM, Saada A, Beinat M, Karicheva O, Mandel H, Ofek N, Segel R, et al. Acute infantile liver failure due to mutations in the TRMU gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(3):401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.