A study of the visualization of proton relay in cellulase by neutron crystallography.

Keywords: Cellulase, Carbohydrate Active enZymes, Proton relay, Neutron crystallography, biomass, Tautomerization, Phanerochaete chrysosporium

Abstract

Hydrolysis of carbohydrates is a major bioreaction in nature, catalyzed by glycoside hydrolases (GHs). We used neutron diffraction and high-resolution x-ray diffraction analyses to investigate the hydrogen bond network in inverting cellulase PcCel45A, which is an endoglucanase belonging to subfamily C of GH family 45, isolated from the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Examination of the enzyme and enzyme-ligand structures indicates a key role of multiple tautomerizations of asparagine residues and peptide bonds, which are finally connected to the other catalytic residue via typical side-chain hydrogen bonds, in forming the “Newton’s cradle”–like proton relay pathway of the catalytic cycle. Amide–imidic acid tautomerization of asparagine has not been taken into account in recent molecular dynamics simulations of not only cellulases but also general enzyme catalysis, and it may be necessary to reconsider our interpretation of many enzymatic reactions.

INTRODUCTION

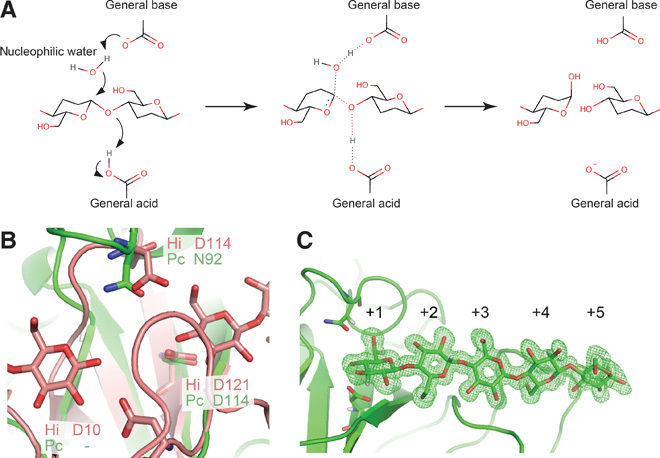

Hydrolase (Enzyme Commission no. 3) is the largest category of enzymes; they mediate chemical bond cleavage via the addition of a water molecule, and the catalytic residues serve to assist nucleophilic attacks of the oxygen atom of water through donating and accepting protons. Hydrolases acting on carbohydrates are called glycoside hydrolases (GHs), and they play central roles in metabolism and utilization of carbohydrates in nature. They are divided into two major groups with different hydrolytic mechanisms: retaining hydrolases afford a product with the same anomeric configuration as the substrate, whereas inverting hydrolases afford a product with the opposite anomeric configuration to the substrate (1). Both types of enzymes commonly use two acidic amino acids, typically aspartic and/or glutamic acids, at the catalytic center. Retaining glycosidases exhibit a two-step mechanism, with one of the two key catalytic residues acting as a nucleophile and the other as an acid/base; in the first step, the nucleophile attacks the anomeric center with the aid of the acidic residue to afford a glycosyl enzyme intermediate, and then the deprotonated residue serves as a base to hydrolyze the intermediate. On the other hand, in inverting enzymes, one residue serves as a general acid that protonates the glycosyl oxygen atom and the other acts as a general base that activates water to directly hydrolyze the glucosidic bond (Fig. 1A). Currently, 127 GH families are registered in the Carbohydrate Active enZymes (CAZy) database (2), and 43 of them are reported to exhibit an inverting mechanism, although the catalytic residues and mechanisms of some remain unclear (3–5).

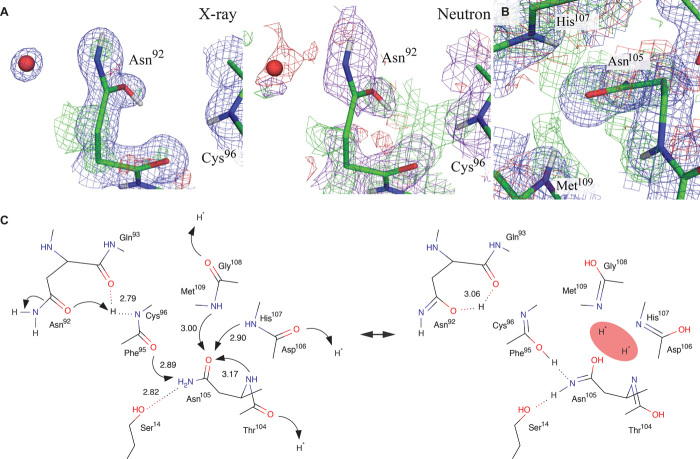

Fig. 1. Proposed reaction mechanism of inverting cellulase and the close-up views of catalytic site of PcCel45A.

(A) Reaction scheme of inverting cellulase. The general acid should be protonated and the general base should be deprotonated for the reaction. (B) Comparison of residues around the catalytic centers of HiCel45A (pink) and PcCel45A (green). (C) X-ray omit map of cellopentaose at subsites +1 to +5 of PcCel45A WT at room temperature (2σ level).

Among GHs, cellulases hydrolyze β-1,4-glucosidic bonds of cellulose, the most abundant biopolymer on earth, and they are therefore of commercial interest for biomass utilization to obtain bioethanol and other chemical compounds. In particular, the inverting cellulases of family 45 are diverse, being found in microorganisms such as bacteria, yeasts, molds, and mushrooms, as well as insects and shellfish. For example, endoglucanase (EG) from the mold Humicola insolens (HiCel45A) is widely used as an industrial cellulase in detergents and in the textile industry. We recently discovered a similar EG (PcCel45A), which has been classified into subfamily C of GH family 45, in the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium (6). PcCel45A hydrolyzes cellulose to afford α-cellooligosaccharides via an inverting mechanism (fig. S1), even though it lacks one of the two catalytically important acidic residues found in HiCel45A (7). To understand the proton transfer network in PcCel45A, we used a combination of high-resolution x-ray crystallography (8) and neutron crystallography, which can visualize hydrogen atoms (9).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structural determination and catalytic residues of PcCel45A

We initially obtained crystals of PcCel45A fortuitously during storage of this enzyme in a refrigerator, and the phase was determined by the multiple isomorphous replacement method (Pt and Au labels; table S1). However, crystallization under these conditions was not reproducible. Finally, after detailed investigation, we were able to obtain large-volume crystals (>6 mm3) suitable for neutron crystallography by crystallization in the presence of 3-methyl-1,5-pentanediol (3MPD) as a precipitant. In addition, high-quality crystal of unliganded PcCel45A suitable for ultrahigh-resolution x-ray crystallography was prepared under microgravity conditions at the Protein Crystallization Research Facility of “Kibo,” the Japanese Experiment Module (JEM) of the International Space Station (ISS). We determined seven high-resolution x-ray structures for wild-type PcCel45A (WT) and mutants of PcCel45A under cryogenic conditions (tables S2 to S4 and S7) and two high-resolution x-ray/neutron structures with and without cellopentaose as a ligand at room temperature (tables S5 and S6). The structure of WT with cellopentaose was determined at 0.64-Å resolution, which is the highest-resolution structure of a catalytic enzyme currently available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). As shown in fig. S2, PcCel45A has a six-stranded β barrel structure with a third strand and five disulfide bonds, sharing a similar core structure to HiCel45A, although the presence and conformation of loops are somewhat different. Comparing the residues around the catalytic centers in PcCel45A and HiCel45A (Fig. 1B), Asp114 of PcCel45A is located at a similar position to the general acid residue (Asp121) of HiCel45A, whereas no acidic amino acid corresponding to the general base residue (Asp10) or assisting residue (Asp114) in HiCel45A was found in PcCel45A. Asparagine (Asn92), but not aspartic acid, was found in PcCel45A at the position of the assisting residue of HiCel45A. To determine the function of the catalytic residues of PcCel45A, we compared the activities of two mutants (Asp114 to asparagine, D114N, and Asn92 to aspartate, N92D) toward amorphous cellulose with that of WT over the pH range of 3 to 8.5 (fig. S3). D114N mutant, which lacks the putative general acid, was inactive (less than 0.002 min−1), indicating the importance of this residue for cellulose hydrolysis. The activity of the N92D mutant was also markedly decreased, and only small amounts of products were detected at around pH 5.5. These results imply that Asn92 acts as a catalytic residue, and asparagine is more effective than aspartic acid for hydrolysis by PcCel45A.

Comparison of structures at room temperature and cryo-temperature

The structures of unliganded WT and cellopentaose-liganded WT were determined at 1.0-Å resolution by x-ray diffraction analysis and at 1.5-Å resolution by neutron diffraction analysis at room temperature. Although the resolution was lower than that obtained at cryogenic temperature, the structure obtained at room temperature is clearly different from that at cryogenic temperature. For example, the number of water molecules observed in the structure at room temperature was almost half of the number at cryogenic temperature (fig. S4A), suggesting that firmly and loosely bound water molecules can be discriminated from a comparison of the two conditions. Moreover, in the unliganded structure at cryogenic temperature, clear density of tris molecule was observed at subsite +1 (fig. S4B), and the conformation of Asn92 was flipped from that in room temperature. We examined the inhibition of the catalytic reaction by tris (fig. S3C) because the conformation of Asn92 with the tris molecule is close to that in the cellopentaose-liganded structure, in which interactions occur with O6 of the reducing and nonreducing end of cellopentaose (Fig. 1C and figs. S5 and S6). However, a high concentration of tris (1.0 M) did not inhibit the enzyme at all, suggesting that the observation at cryogenic temperature is an artifact.

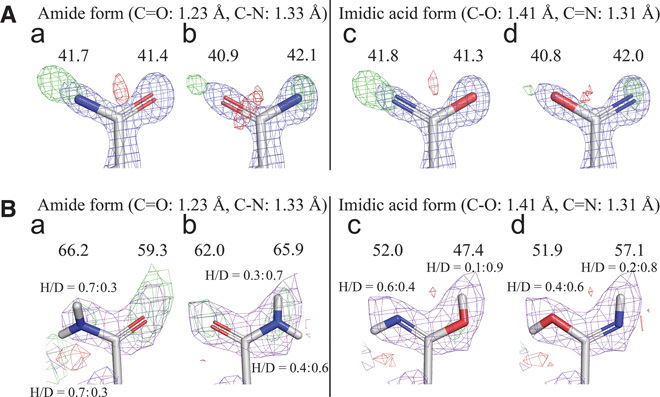

Determination of imidic acid form of Asn92

The orientation and protonation/deuteration state of Asn92 were next examined by x-ray (Fig. 2A, a to d) and neutron (Fig. 2B, a to d) crystallography. When the oxygen atom was facing the catalytic center, a strongly positive Fobs − Fcalc map was observed around the nitrogen atom in the x-ray analysis (Fig. 2A, a). In contrast, positive and negative Fobs − Fcalc maps were observed at the top and bottom of the oxygen atom, respectively, when the nitrogen atom was facing the catalytic center (Fig. 2A, b). The imidic acid form of Asn92, where the nitrogen atom faces the catalytic center, showed the weakest Fobs − Fcalc map in the x-ray analysis (Fig. 2A, d). In the neutron structure, strongly positive Fobs − Fcalc maps, which reflect deuteration/protonation of oxygen, were observed around the oxygen atom in the amide form of Asn92 (Fig. 2B, a and b). The hydrogen/deuterium (H/D) ratio was 0.3:0.7 under the crystallization conditions because of the difficulty of preparing fully deuterated 3MPD, and the H/D ratio of the imidic acid form of Asn92 is consistent with that value (Fig. 2B, d). The combined x-ray and neutron crystallography results indicate that the side chain of the asparagine residue takes the imidic acid form (HO–CX=NH), but not the typical amide form (O=CX–NH2), providing the first direct evidence that the imidic acid plays a key role in the hydrolysis.

Fig. 2. Detailed analysis of protonation state of Asn92 by x-ray and neutron crystallographies.

(A) Determination of orientation and form of Asn92 at room temperature by x-ray diffraction. B-factor values (Å2) are shown above atoms (2Fobs − Fcalc map: 1.5σ in blue, Fobs − Fcalc map: 3.0σ in green and red for positive and negative). (B) Determination of orientation and protonation/deuteration of Asn92 at room temperature by neutron diffraction. B-factor values (Å2) of oxygen and nitrogen atoms are shown above atoms. Ratios of H/D are also shown (2Fobs − Fcalc map: 1.0σ in purple, Fobs − Fcalc map: 2.0σ in green and red for positive and negative).

Formation and stabilizing mechanism of imidic acid form of asparagine residue

The pKa value for protonation of carbonyl oxygen of the imidic acid form was estimated as around 0 (10), and that of protonation/deprotonation of nitrogen was estimated as 4.5 to 7.5 (11, 12). Thus, the nitrogen atom of the imidic acid form of asparagine can act as a base in PcCel45A, although it is not yet clear how the oxygen atom of asparagine is protonated. The x-ray and neutron H/D omit maps around the imidic acid of Asn92 are shown in Fig. 3A. The positive Fobs − Fcalc map in the neutron analysis connects the nitrogen atoms of neighboring amides of Cys96 and oxygen atoms of side and main chains of Asn92, although nothing was observed in the x-ray structure. Considering that x-rays are scattered by electrons, whereas neutrons are scattered by the nucleus, protons/deuterons only show up in the neutron diffraction analysis. For example, the positions of protons in zeolite were determined by neutron powder diffraction analysis (13), and the proton dynamics in N-methylacetamide was studied by inelastic neutron scattering (14). Intramolecular proton transfer at hydrogen bonds between carbonyl and amide of small molecules often occurs if the positions of nitrogen and oxygen are suitable (15). In addition, the possibility of proton transfer between protonated carbonyl of the main chain and carbonyl of the side chain of Asn92 was indicated by a theoretical study of analogs of malonaldehyde (16). These results all support the idea that proton/deuteron transfer from the amide of Cys96 to the carbonyl of the side chain of Asn92 can occur, and this would be consistent with stabilization of the imidic acid form of Asn92 by multiple tautomerizations at the surface of the enzyme, that is, the side-chain carbonyl group of Asn105 is highly protonated/deuterated by a “proton sink” consisting of amides of His107, Met109, and the main chain of Asn105 (Fig. 3B), and thus, the side-chain amide group of Asn105 can transfer a proton/deuteron to carbonyl of Phe95 via the imidic acid form, such as Asn92, and the amide of Cys96 passes the proton/deuteron to carbonyl of Asn92 (Fig. 3C). The proton network originating from the proton sink was not seen at all in subatomic x-ray structures PcCel45A (~0.64 Å), emphasizing the importance of neutron crystallography for visualizing the localization of protons.

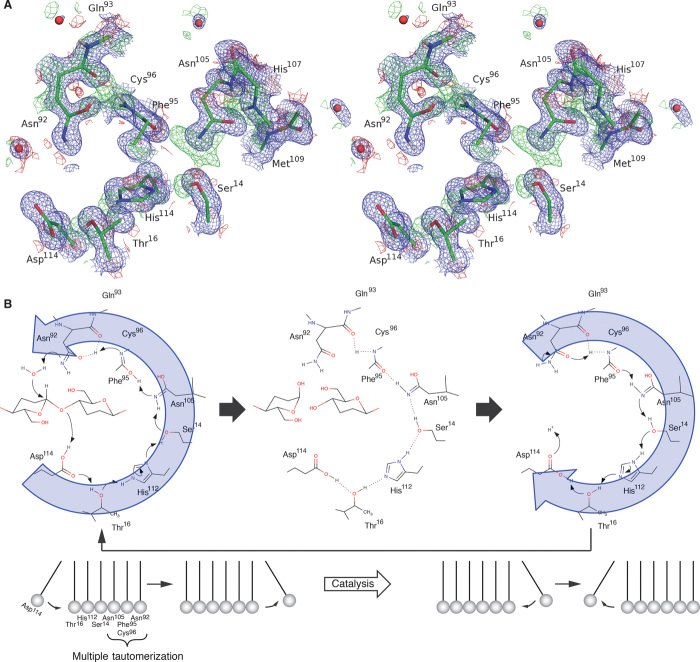

Fig. 3. Proton relay stabilizing the imidic acid state of Asn92.

(A) Difference maps calculated without H/D atoms around carbonyl oxygen atoms of Asn92 and the amide of Cys96. The 2Fobs − Fcalc (blue) and Fobs − Fcalc (red and green) maps of the x-ray analysis are shown at the 1.0σ and 3.0σ levels, respectively, and 2Fobs − Fcalc (purple) and Fobs − Fcalc (red and green) maps of the neutron analysis are shown at the 1.0σ and 2.0σ levels, respectively. (B) Difference maps calculated without H/D atoms around carbonyl oxygen atoms of Asn105 and amide of Asn105, His107, and Met109. The 2Fobs − Fcalc map of the x-ray analysis is shown at the 1.0σ level, and the Fobs − Fcalc map of the neutron analysis is shown at the 2.0σ level. (C) Proposed mechanism of formation of the imidic acid form of Asn92.

Catalytic mechanism of PcCel45A with proton relay between catalytic residues

Furthermore, when hydrogens/deuteriums of Ser14, His112, and Thr16 are omitted (Fig. 4A), another proton/deuteron network appears from Asn92 (imidic acid form) to Asp114, which serve as a general base and a general acid, respectively, via Asn105, indicating that the catalytic acid and base residues act as a proton relay during the hydrolysis. After the oxygen atom of the imidic acid form of Asn92 passes the proton back to the amide of Cys96, the nitrogen atom of the Asn92 will be activated, accepting a proton from nucleophilic water. At the same time, the oxygen atom of Phe95 returns a proton to the side chain of Asn105, and a proton is further transferred to the hydroxyl group of Ser14 because of the stabilization of the imidic acid form of Asn105 by the multiple tautomerizations (Fig. 3B). The proton relay is further connected sequentially to the side chains of His112 and Thr16, and the side-chain carbonyl group of Asp114 finally accepts a proton and donates a proton to the oxygen atom of glycosidic bond (Fig. 4B and fig. S7). After the hydrolytic reaction, protonation of Asp114 promotes the regeneration of the imidic acid form of Asp92 by reverse relay (movie S1). In inverting GHs, the catalytic mechanism always lacks the process of return to the resting state of the enzyme with protonation of acid and deprotonation of base. Thus, the combined x-ray and neutron analysis has finally allowed us to visualize the complete catalytic cycle of the inverting GH, including the “Newton’s cradle”–like proton relay pathway based on multiple back-and-forth Grotthuss mechanisms during the catalysis. The proposed mechanism is consistent with the pH dependence of PcCel45A WT, which shows the highest activity at lower pH, and is also consistent with the lower activity of N92D than WT (fig. S3), because the general base is unable to work well in carboxylic acid form with protonation by the amide of Cys96. The loop region including Asn92 in the N105D mutant at pH 8.0 was disordered, and Ser14 showed double conformers (fig. S8A), whereas N105D retained 74% of the activity of WT at pH 3.0 (fig. S8B). These results support the idea that the protonation of Asn105, which is located in the middle of the proton pathway, is important for the catalytic cycle of PcCel45A.

Fig. 4. Proton pathway between catalytic residues and expected catalytic mechanism of PcCel45A.

(A) Difference map calculated without H/D atoms in the proton relay pathway in stereo view. The 2Fobs − Fcalc map (blue) of the x-ray analysis is shown at the 1.0σ level, and the Fobs − Fcalc map (red and green) of the neutron analysis is shown at the 2.0σ level. (B) Proposed Newton’s cradle–like reaction mechanism of PcCel45.

CONCLUSION

Although the importance of proton relay has long been discussed in many enzyme reactions (17, 18), we have demonstrated the great diversity of protonation states of side chains of PcCel45A relevant to the catalytic reaction, and in particular, we have established the importance of multiple tautomerizations in the proton relay pathway by means of neutron diffraction analysis. So far, less than 80 protein structures determined by neutron diffraction are available in PDB, in contrast to about 100,000 x-ray structures, possibly because of the difficulty of preparing the huge crystals, typically more than 1 mm3, that are required for neutron diffraction analysis. A recent high-resolution x-ray structural study of a [NiFe] hydrogenase (19) indicated that x-ray crystallography can be highly effective for visualizing hydrogens in a protein molecule. However, considering that our ultrahigh-resolution x-ray structures of PcCel45A failed to show many protons that were visualized by neutron crystallography, we consider that the combination of neutron and x-ray crystallography is still a powerful approach to elucidate the functions of proton networks in proteins and the mechanisms of enzyme reactions. Our findings suggest that multiple tautomerizations may play a key role in the hydrolytic cycle of other inverting GH enzymes, whose complete catalytic mechanisms have not yet been determined. Moreover, amide–imidic acid structural conversion has not been taken into account in molecular dynamics simulations of enzyme catalysis involving asparagine and glutamine as catalytic residues, and therefore, our understanding of many enzymatic reactions may need to be reconsidered.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production and purification of PcCel45A WT and mutants

The genes coding N92D, D114N, and N105D mutants were produced by site-directed mutagenesis. PcCel45A WT and mutants were produced in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris as a host according to a previous report (6). All three enzymes were purified by anion exchange and hydrophobic interaction column chromatographies (20). Purity was checked by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and native-PAGE (fig. S9).

Activity measurement of PcCel45A WT and mutants

The anomeric forms of products generated from phosphoric acid–swollen cellulose (PASC) by PcCel45A were determined by a modification of the method reported previously (21). PcCel45A (50 μM) was incubated with 1.0% PASC in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) at 30°C for 1 min, and the soluble products were separated by means of a 0.22-μm polyvinylidene difluoride filter. An aliquot of the filtrate was immediately subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The products were separated on a TSKgel Amide-80 column (Tosoh Bioscience) at 30°C with a gradient of acetonitrile from 80 to 60% (v/v) and detected with a Corona Charged Aerosol Detector (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K.). The anomer ratio of standard oligosaccharides and products after 120 min of incubation at 30°C was also examined by the same method. The activity of PcCel45A WT and mutants toward PASC at various pH values was measured by HPLC. The buffers were sodium citrate for pH 3.0 and 3.5, sodium acetate for pH 4.0 to 5.5, sodium phosphate for pH 6.0 to 7.0, and tris-HCl for pH 7.5 to 8.5. A 1 μM enzyme solution in buffer was incubated with 0.5% PASC in 50 mM buffer for 1 hour at 30°C, and the supernatant after centrifugation was collected. Soluble products were separated on an NH2P-50 4E column (Showa Denko K.K.) and quantified with a Corona Charged Aerosol Detector using the method reported previously (6). Amounts of soluble products were summed, and the production velocity was calculated. The inhibitory effect of tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane was measured in 50 mM sodium citrate (pH 3.0) at 30°C. The products formed by 1.0 μM PcCel45A WT from 0.5% PASC were measured using the same methods.

Phase determination of PcCel45A

The PcCel45A crystals used for initial structure determination appeared in the purified protein solution containing 20 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0) buffer and 1.0 M ammonium sulphate after being stored at 4°C for several months. For the native data set, the crystal was soaked in 3 M ammonium sulphate solution containing the same buffer and flash-cooled at nitrogen stream. To obtain the heavy atom derivative data sets, PcCel45A crystals were soaked in mother liquor containing 5 mM AuCl3 or K2Pt(CN)4 for 3 hours before data collection. All diffraction data sets used for phasing and initial structure determination were processed and scaled using the HKL2000 program suite (22) available at the beamline. Multiple isomorphous replacement with the anomalous scattering (MIRAS) method was applied for the initial phase determination using AutoSol in the PHENIX program suite (23). DM and ARP/wARP in the CCP4I program suites were used for the density modification and automated model building, respectively (24). Manual model rebuilding and refinement were conducted by using Coot (25) and REFMAC5 (26).

Crystallization and data collection for x-ray crystallography

For the unliganded structure of PcCel45A N92D, D114N, or N105D, the enzyme (40 mg/ml) was crystallized in 50 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.5, 8.5, or 8.0, respectively) and 65% 3MPD by the sitting-drop method at 20°C. The crystals were trapped on nylon loops, and diffraction data were collected after flash cooling. Unliganded crystals of PcCel45A WT were made by the counter diffusion method. Protein solution (40 mg/ml) was filled in a glass capillary and connected to precipitant solution containing 60% 3MPD and 50 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0) by 1% agarose gel. The crystallization instrument was incubated at 20°C for about 3 months in the ISS. The crystals were mounted in the capillaries because they could not be easily removed. Crystals with cellopentaose were made by cocrystallization as follows. Enzyme (40 mg/ml) was mixed with 5 mM cellopentaose (enzyme/cellopentaose = 1:2 in mol/mol) and incubated in 20°C for one night. The complex was crystallized by the sitting-drop method with 60% 3MPD at 20°C. To avoid saturation of the diffraction spots, diffraction data in three or two resolution ranges (high, mid and low, or high and low) were collected and merged into one data set. All of the data were processed by HKL2000 virus mode or XDS (27) and refined by PHENIX and Coot.

Crystallization and data collection for neutron and x-ray crystallography at room temperature

Large (6 mm3) crystals of PcCel45A WT with and without 2.5 mM cellopentaose were made by the sitting-drop method in D2O with control of nucleation and crystal growth according to a previous report (20). The crystals were encapsulated in quartz capillaries (ϕ = 3.5 mm and thickness 0.01 mm) with reservoir solution containing enzyme (5 mg/ml) or enzyme-cellopentaose complex. Neutron diffraction data were collected at 25°C by iBIX in J-PARC (28, 29). Subsequently, x-ray diffraction data of the same crystals were collected at 25°C. Neutron diffraction data were processed using STARGazer (30), and x-ray diffraction data were processed using HKL2000. Refinement of x-ray data and joint refinement of neutron and x-ray data were done by PHENIX (31) and Coot. The restrained file of the imidic acid form of asparagine acid was made with the default setting of eLBOW in the PHENIX suite (32). A 1-mm3 crystal of N92D was prepared by the same method, and x-ray diffraction data were collected at 25°C. Diffraction data were processed by using XDS and refined by using PHENIX and Coot.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The x-ray data were collected in the Photon Factory (2013G194, 2013G191) and Spring-8 BL44XU (2013A6802, 2013B6802). The neutron data were collected at iBIX in J-PARC (2012PX0008, 2013PX0006, and 2014PX0003) operated by Ibaraki prefecture. Funding: This research was supported in part by Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) “High-Quality Protein Crystal Growth Experiment on JEM” and JAXA Open-Laboratory program. A Russian spacecraft provided by the Russian Federal Space Agency was used for space transportation. The European Space Agency (ESA) and the University of Granada developed a part of the space crystallization technology. This research was also supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Innovative Areas from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, and Technology (MEXT) to K. Igarashi (nos. 24114001 and 24114008); a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) to K. Igarashi (B: no. 24380089); a Coordination Funds for Promoting AeroSpace Utilization (no. A3D26195) from MEXT to K. Igarashi; and a Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows to A.N. (25•7574) from JSPS. Author contributions: A.N. and K. Igarashi designed the research and wrote the paper. A.N. mainly performed the experiments and analyzed data. T.I., S.F., K. Inaka, and Y.H. took and analyzed x-ray diffraction data. K.K., T.Y., I.T., and N.N. took and supported neutron diffraction experiments. K.O., H.T., and K. Inaka managed protein crystallization research under microgravity condition. S.K. and M.S. contributed to the discussion of this research. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/7/e1500263/DC1

Table S1. Data collection, phasing, and refinement statistics for first structural determination of PcCel45A.

Table S2. Statistics of data collection and refinement of the x-ray structure of PcCel45A WT with and without 5 mM cellopentaose at cryogenic temperature.

Table S3. Statistics of data collection and refinement of the x-ray structure of PcCel45A N92D with and without cellopentaose at cryogenic temperature and PcCel45A N92D unliganded structure at room temperature.

Table S4. Statistics of data collection and refinement of the x-ray structure of PcCel45A D114N with and without 5 mM cellopentaose at cryogenic temperature.

Table S5. Statistics of data collection and refinement of the neutron and x-ray structure of PcCel45A WT unliganded.

Table S6. Statistics of data collection and refinement of the neutron and x-ray structure of PcCel45A WT with 2.5 mM cellopentaose.

Table S7. Statistics of data collection and refinement of the x-ray structure of PcCel45A N105D.

Fig. S1. Determination of anomeric forms of products.

Fig. S2. Structural comparison of PcCel45A with other GH45 enzymes.

Fig. S3. Activity profile of PcCel45A WT and mutants.

Fig. S4. Temperature effect on PcCel45A structure.

Fig. S5. Substrate recognition of PcCel45A WT and mutants.

Fig. S6. Joint refined structure of PcCel45A WT with 2.5 mM cellopentaose.

Fig. S7. Neighboring pair residues in the proton relay pathway.

Fig. S8. Structural and activity profile of PcCel45A N105D mutant.

Fig. S9. SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE of PcCel45A WT and mutants.

Movie S1. The proposed proton relay pathway between Asp92 (general base) and Asn114 (general acid) residues in PcCel45A.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.McCarter J. D., Stephen Withers G., Mechanisms of enzymatic glycoside hydrolysis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 4, 885–892 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lombard V., Golaconda Ramulu H., Drula E., Coutinho P. M., Henrissat B., The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D490–D495 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsiegla G., Reverbel C., Tardif C., Driguez H., Haser R., Structures of mutants of cellulase Cel48F of Clostridium cellulolyticum in complex with long hemithiocellooligosaccharides give rise to a new view of the substrate pathway during processive action. J. Mol. Biol. 375, 499–510 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koivula A., L. Ruohonen, G. Wohlfahrt, T. Reinikainen, T. T. Teeri, K. Piens, M. Claeyssens, M. Weber, A. Vasella, D. Becker, M. L. Sinnott, J. Zou, G. J. Kleywegt, M. Szardenings, J. Ståhlberg, T. A. Jones, The active site of cellobiohydrolase Cel6A from Trichoderma reesei: The roles of aspartic acids D221 and D175. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 10015–10024 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abbott D. W., Macauley M. S., Vocadlo D. J., Boraston A. B., Streptococcus pneumoniae endohexosaminidase D, structural and mechanistic insight into substrate-assisted catalysis in family 85 glycoside hydrolases. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11676–11689 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Igarashi K., Ishida T., Hori C., Samejima M., Characterization of an endoglucanase belonging to a new subfamily of glycoside hydrolase family 45 of the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5628–5634 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies G. J., Tolley S. P., Henrissat B., Hjort C., Schulein M., Structures of oligosaccharide-bound forms of the endoglucanase V from Humicola insolens at 1.9 Å resolution. Biochemistry 34, 16210–16220 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higashiura A., T. Kurakane, M. Matsuda, M. Suzuki, K. Inaka, M. Sato, T. Kobayashi, T. Tanaka, H. Tanaka, K. Fujiwara, A. Nakagawa, High-resolution X-ray crystal structure of bovine H-protein at 0.88 Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 698–708 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niimura N., Bau R., Neutron protein crystallography: Beyond the folding structure of biological macromolecules. Acta Crystallogr. A Found. Crystallogr. 64, 12–22 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fersht A. R., Jencks W. P., Acetylpyridinium ion intermediate in pyridine-catalyzed hydrolysis and acyl transfer reactions of acetic anhydride. Observation, kinetics, structure–reactivity correlations, and effects of concentrated salt solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 92, 5432–5442 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaturvedi R. K., Schmir G. L., The hydrolysis of N-substituted acetimidate esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 90, 4413–4420 (1968). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pletcher T. C., Koehler S., Cordes E. H., Mechanism of hydrolysis of N-methylacetimidate esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 90, 7072–7076 (1968). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Czjzek M., Jobic H., Fitch A. N., Vogt T., Direct determination of proton positions in D–Y and H–Y zeolite samples by neutron powder diffraction. J. Phys. Chem. 96, 1535–1540 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fillaux F., Fontaine J. P., Baron M. H., Kearley G. J., Tomkinson J., Inelastic neutron-scattering study of the proton dynamics in N-methylacetamide at 20 K. Chem. Phys. 176, 249–278 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilli P., Bertolasi V., Pretto L., Lyčka A., Gilli G., The nature of solid-state N–H⋯O/O–H⋯N tautomeric competition in resonant systems. Intramolecular proton transfer in low-barrier hydrogen bonds formed by the ⋯O=C–C=N–NH⋯ ⇆ ⋯HO–C=C–N=N⋯ ketohydrazone–azoenol system. A variable-temperature X-ray crystallographic and DFT computational study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 13554–13567 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheiner S., Kar T., Čuma M., Excited state intramolecular proton transfer in anionic analogues of malonaldehyde. J. Phys. Chem. A 101, 5901–5909 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimokata K., Katayama Y., Murayama H., Suematsu M., Tsukihara T., Muramoto K., Aoyama H., Yoshikawa S., Shimada H., The proton pumping pathway of bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 4200–4205 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baradaran R., Berrisford J. M., Minhas G. S., Sazanov L. A., Crystal structure of the entire respiratory complex I. Nature 494, 443–448 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogata H., Nishikawa K., Lubitz W., Hydrogens detected by subatomic resolution protein crystallography in a [NiFe] hydrogenase. Nature 520, 571–574 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura A., Ishida T., Fushinobu S., Kusaka K., Tanaka I., Inaka K., Higuchi Y., Masaki M., Ohta K., Kaneko S., Niimura N., Igarashi K., Samajima M., Phase-diagram-guided method for growth of a large crystal of glycoside hydrolase family 45 inverting cellulase suitable for neutron structural analysis. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 20, 859–863 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishida T., Fushinobu S., Kawai R., Kitaoka M., Igarashi K., Samejima M., Crystal structure of glycoside hydrolase family 55 β-1,3-glucanase from the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 10100–10109 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otwinowski Z. and Minor W., Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams P. D., Afonine P. V., Bunkóczi G., Chen V. B., Davis I. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Hung L.-W., Kapral G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Oeffner R., Read R. J., Richardson D. C., Richardson J. S., Terwilliger T. C., Zwart P. H., PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winn M. D., Ballard C. C., Cowtan K. D., Dodson E. J., Emsley P., Evans P. R., Keegan R. M., Krissinel E. B., Leslie A. G. W., McCoy A., McNicholas S. J., Murshudov G. N., Pannu N. S., Potterton E. A., Powell H. R., Read R. J., Vagin A., Wilson K. S., Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. D67, 235–242 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K., Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vagin A. A., Steiner R. A., Lebedev A. A., Potterton L., McNicholas S., Long F., Murshudov G. N., REFMAC5 dictionary: Organization of prior chemical knowledge and guidelines for its use. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2184–2195 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kabsch W., XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka I., Kusaka K., Hosoya T., Niimura N., Ohhara T., Kurihara K., Yamada T., Ohnishi Y., Tomoyori K., Yokoyama T., Neutron structure analysis using the IBARAKI biological crystal diffractometer (iBIX) at J-PARC. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 1194–1197 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kusaka K., Hosoya T., Yamada T., Tomoyori K., Ohhara T., Katagiri M., Kurihara K., Tanaka I., Niimura N., Evaluation of performance for IBARAKI biological crystal diffractometer iBIX with new detectors. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 20, 994–998 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohhara T., Kusaka K., Hosoya T., Kurihara K., Tomoyori K., Niimura N., Tanaka I., Suzuki J., Nakatani T., Otomo T., Matsuoka S., Tomita K., Nishimaki Y., Ajima T., Ryufuku S., Development of data processing software for a new TOF single crystal neutron diffractometer at J-PARC. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 600, 195–197 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams P. D., Mustyakimov M., Afonine P. V., Langan P., Generalized X-ray and neutron crystallographic analysis: More accurate and complete structures for biological macromolecules. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 65, 567–575 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moriarty N. W., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., electronic Ligand Builder and Optimization Workbench (eLBOW): A tool for ligand coordinate and restraint generation. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 65, 1074–1080 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/7/e1500263/DC1

Table S1. Data collection, phasing, and refinement statistics for first structural determination of PcCel45A.

Table S2. Statistics of data collection and refinement of the x-ray structure of PcCel45A WT with and without 5 mM cellopentaose at cryogenic temperature.

Table S3. Statistics of data collection and refinement of the x-ray structure of PcCel45A N92D with and without cellopentaose at cryogenic temperature and PcCel45A N92D unliganded structure at room temperature.

Table S4. Statistics of data collection and refinement of the x-ray structure of PcCel45A D114N with and without 5 mM cellopentaose at cryogenic temperature.

Table S5. Statistics of data collection and refinement of the neutron and x-ray structure of PcCel45A WT unliganded.

Table S6. Statistics of data collection and refinement of the neutron and x-ray structure of PcCel45A WT with 2.5 mM cellopentaose.

Table S7. Statistics of data collection and refinement of the x-ray structure of PcCel45A N105D.

Fig. S1. Determination of anomeric forms of products.

Fig. S2. Structural comparison of PcCel45A with other GH45 enzymes.

Fig. S3. Activity profile of PcCel45A WT and mutants.

Fig. S4. Temperature effect on PcCel45A structure.

Fig. S5. Substrate recognition of PcCel45A WT and mutants.

Fig. S6. Joint refined structure of PcCel45A WT with 2.5 mM cellopentaose.

Fig. S7. Neighboring pair residues in the proton relay pathway.

Fig. S8. Structural and activity profile of PcCel45A N105D mutant.

Fig. S9. SDS-PAGE and Native-PAGE of PcCel45A WT and mutants.

Movie S1. The proposed proton relay pathway between Asp92 (general base) and Asn114 (general acid) residues in PcCel45A.