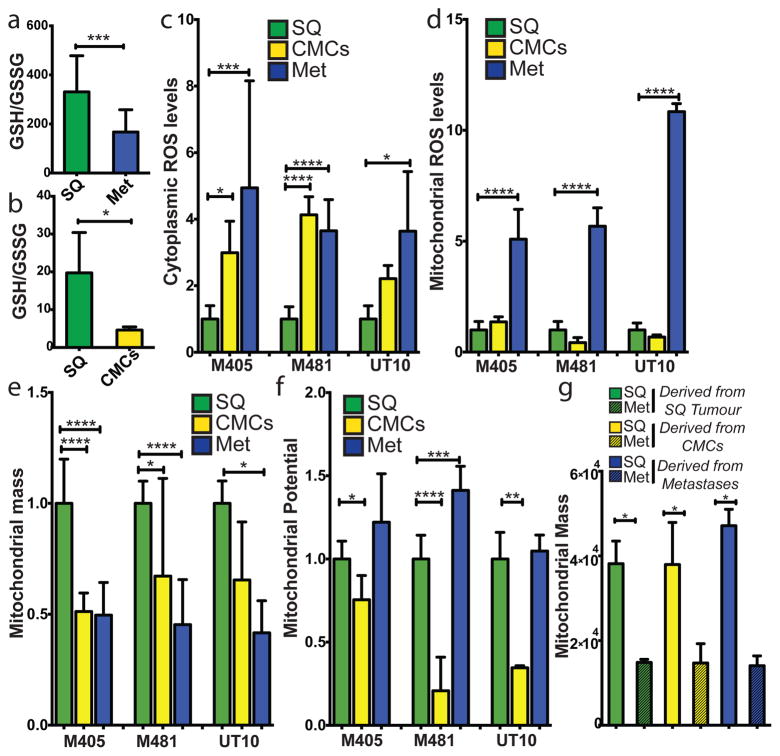

Figure 1. Metastasizing melanoma cells experience high levels of oxidative stress.

a) GSH/GSSG ratio in subcutaneous tumours as compared to metastatic nodules (n=15 mice from 2 independent experiment with 3 melanomas, M481, M405, UT10; note that extractions were performed with 0.1% formic acid to prevent spontaneous oxidation47). Total amounts of GSH and GSSG are shown in Extended data Figure 5h and 5i. b) GSH/GSSG ratio in subcutaneous tumours as compared to circulating melanoma cells (n=7 mice from 3 independent experiments with 2 melanomas, M405 and UT10; these were different experiments than those in panel a, performed under different technical conditions). c, d) cytoplasmic (c) and mitochondrial (d) ROS levels in dissociated melanoma cells from subcutaneous tumours, the blood, and metastatic nodules obtained from the same mice (n=9 mice from 3 independent experiments using 3 different melanomas). e, f) Mitochondrial mass (e) and mitochondrial membrane potential (f) in dissociated melanoma cells from subcutaneous tumours, the blood, and metastatic nodules obtained from the same mice (n=6 mice from 2 independent experiments using 3 different melanomas). g) Melanoma cells underwent reversible changes in mitochondrial mass during metastasis: mitochondrial mass in dissociated melanoma cells from subcutaneous tumours versus metastatic nodules obtained from the same mice transplanted with subcutaneous, circulating, or metastatic melanoma cells. All data represent mean±sd. Statistical significance was assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests (a and b) and one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) followed by Dunnett’s tests for multiple comparisons (c–g; *, p<0.05; ***, p< 0.0005; ****, p<0.00005).