Figure 3.

Computational and Experimental Validation of the DoS Identified by KINspect

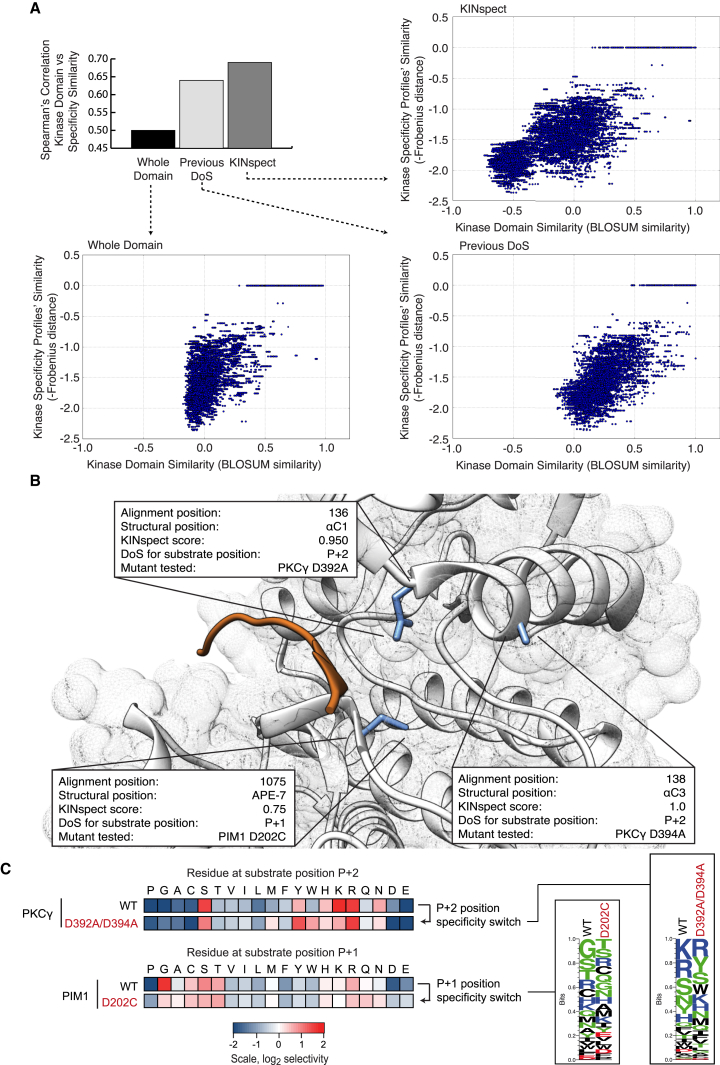

(A) Scatterplots comparing pairwise relationships between kinases’ domain sequences, and their specificity profiles can illustrate the lack or existence of correlation between sequence and specificity. By limiting the comparison to specific sets, one can investigate whether such sets encode for specificity (i.e., maintain or increase the correlation), as measured by Spearman’s correlation coefficients. By comparing the correlations obtained from different sets of residues, the whole domain on the left, previously reported determinants of specificity in the middle and KINspect scores on the right, we confirm that residues with a high KINspect score encode for specificity (e.g., residues scoring above 0.9 lead to very high sequence-to-specificity correlation, with a Spearman’s correlation coefficient of 0.69, despite representing only 5.73% of the residues in the kinase domain alignment). Further comparisons with other sets of residues can be found in Figure S4.

(B) Three new candidate determinants of specificity predicted by KINspect, positioned in the first and third residues of the αC helix and seven residues before the APE motif delimiting the activation segment, are experimentally verified to encode specificity by PSPL as described in Experimental Procedures.

(C) Experimental results for the PKCγ and PIM1 mutants showing a specificity switch for P+2 and P+1 substrate positions, as shown in matrix and logo form (logos generated using Seq2Logo; Thomsen and Nielsen, 2012). Complete PSSMs describing the PSPL results for wild-type and mutant kinases can be found in Figure S4.