Abstract

Context

Family caregivers (FCGs) are often at the frontline of symptom management for patients with advanced illness in home hospice. FCGs’ cognitive, social and technical skills in complex medication management have been well studied in the literature; however, few studies have tested existing frameworks in clinical cases in home hospice.

Objectives

This study sought to assess the applicability of Lau et al.’s caregiver medication management skills framework in the context of family caregiving in home hospice in order to further the understanding of FCGs’ essential medication management skills.

Methods

This was a secondary data analysis of 18 audio recorded home hospice visits transcribed verbatim; deductive content analysis of caregiver-nurse interactions was conducted. The target sample included FCGs of hospice patients who had cancer diagnoses in hospices located in the greater urban area of the Rocky Mountain West. Caregiver medication management skills were identified and categorized into the five domains of caregiver expertise. Exemplars of each domain were identified.

Results

An average of four medications (SD 3.5) was discussed at each home hospice visit. Medication knowledge skills were observed in the majority of home hospice visits (15 of 18). Teamwork skills were observed in 11 of 18 cases, followed by organizational and personhood skills (10 of 18). Symptom management skills occurred in 12 of 18 cases. An additional two subconstructs of the Personhood domain –1) advocacy for the caregiver and 2) skills in discontinuing medications – were proposed.

Conclusion

These findings support Lau et al.’s framework for caregiver medication management skills and expands upon the existing domains proposed. Future interventions to assess FCGs’ skills are recommended.

Keywords: Hospice, caregiver skills, medication management, symptom management, framework

Introduction

Family caregivers (FCGs) are integral to providing hospice care to patients electing to die at home.1, 2 Prior studies show that the responsibilities for managing patient symptoms and medications in home hospice contribute to FCG stress.3,4 With minimal or no preparation, training, or support, FCGs are expected to assume health management roles and tasks traditionally performed by professional health care providers.5 Prior studies suggest that FCGs lack confidence 6–8 and feel inadequately prepared and supported9–11 to manage medications at home. This inadequate preparation and support for FCGs contributes to poor symptom management and pain control.12 Further, FCGs report being haunted by memories of relatives’ suffering as a result of inadequately treated pain because of mismanaged medication regimens.12

Hospice providers agree that ensuring proper medication management is very important.13 As such, hospice teams employ a variety of strategies to facilitate medication management for caregivers. These include teaching to increase knowledge, providing support for managing the medication regimen, and counseling to overcome attitudinal barriers.13 In addition, establishing trust with the patient and caregiver, promoting self-confidence, and offering relief by providing support and assistance are critically important.14 However, many hospice providers reported difficulty providing teaching and support to caregivers, and indicated that they would greatly benefit from additional resources to help caregivers.13

To address the issue, Lau et al. took the important step of establishing a comprehensive set of interrelated yet distinct domains of skills for effective medication management for home hospice patients.15 Based on interviews with hospice providers and FCGs, Lau et al. identified five domains of FCG skill assessment and support: 1) teamwork; 2) organization; 3) symptom knowledge; 4) medication knowledge; and 5) personhood. These domains establish a multidimensional construct that encompasses a complex set of cognitive, problem-solving, and interpersonal skills and processes directly related to FCG medication management. As such, this construct establishes a foundation for creating standardized tools for FCG skills assessment, and for guiding an appropriate FCG support intervention.

Despite an increasing body of work surrounding the support of FCG skills in medication management,4, 15 little is known about what really transpires during actual home hospice visits. Therefore, we sought to build on Lau et al.’s multidimensional construct by mapping medication-related discussions from actual home hospice visits to their framework. Our overall goal was to apply the framework to learn more about FCG needs, with the purpose of informing pain and symptom management education by hospice nurses. We first describe the occurrence and frequency of specific conversations and challenges mapping to each of the five domains of FCG medication management skills.2 Second, we describe specific examples and strategies nurses used from actual home hospice visits that could inform the development of an intervention to support FCG medication management. These findings can be used to address the needs of FCGs, and to ultimately improve the experiences and outcomes for both FCGs and hospice patients.

Methods

This study involved the secondary analysis of digitally recorded home hospice visits. Approval was provided by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Utah.

Study Design, Data Source, and Participants

We conducted a qualitative content analysis using a deductive approach to explore the feasibility of applying an existing conceptual model to a unique sample.16 The home hospice visits selected for this secondary analysis were drawn from a large parent study addressing hospice cancer caregiving (P01-CA138317).17 Briefly, we recruited cancer patients and their spousal FCGs into the parent study upon enrollment in hospice care from seven hospice agencies in the greater urban area of the Rocky Mountain West. Home hospice visits were audio-recorded to capture interactions. Nurse participants wore a small digital recorder around their necks to audio-record hospice visits of consented families. The current analysis focuses on spousal FCG medication management at end of life.

FCGs were eligible for the parent study if they provided care to a patient diagnosed with cancer who was admitted to a participating home-care hospice program; had the ability to speak/write English; had daily telephone access; received care from a participating hospice nurse; and had the cognitive and physical ability to participate. For the current project, we included initial visits to all hospice enrollees aged 65 or older at the time we conducted this analysis. The first recorded visit was chosen for inclusion in our sample as we hoped earlier visits would include more medication management discussions. Eighteen individuals met these criteria at the time we began analyzing recordings. Prior research has shown that thematic saturation can be reached with as few as 10 interviews in qualitative studies.18

Data Analysis

The audio-records were transcribed to capture conversations related to medications, health interventions requiring a prescription, or interventions that involved administration by another person. These specifically included prescription and over-the-counter medications, topical ointments, oxygen, and medications to relieve symptoms, such as saline eye drops. Prior to transcribing all visits for analysis, we selectively transcribed two transcripts so that three investigators (J.T., L.E., M.R.) could confirm accurate identification of medication-related content. Next, two team members independently content-coded each transcription (J.T., C.L.) using a directed content analytic approach19 to map visit dialogue to the Lau et al. framework, using pre-specified definitions (see Results section for descriptions of each domain). Two team members (J.T., C.L.) developed codes to document examples of specific FCG skill domains that emerged from the data. Codes were assigned to dialogue segments about FCG skills that were raised by the hospice nurse, the FCG, or identified by the study investigators as relevant to FCG medication management during the content analysis. Investigators also noted specific medications, symptoms, and frequently occurring themes. We also looked for medication-related dialogue that did not clearly fit with the five a priori domains. After coding three transcripts, we met to reconcile the coding schema and applied the reconciled codes to all the transcripts. We resolved discrepancies by developing consensus about which domain was exemplified, and then the entire investigator team reviewed decisions.

Results

Home hospice visits averaged 37.3 minutes (SD=14.5). The time from hospice admission and study enrollment to first recorded visit averaged 29 days (SD=48.9), and was, on average, the sixth (SD= 5.7) nurse visit to the home. Average length of stay in hospice was 12 weeks (median=8 weeks, range 2 weeks to one year).

Study Sample

Patient and FCG Characteristics

The study included 18 patients and their FCGs. FCGs were generally younger than patients, and female (Table 1). Of the patients and FCGs who reported race, all were Caucasian; seven individuals did not provide information on race). It was common for additional FCGs to be present and interact with the nurse during visits. The most common cancer diagnosis was prostate cancer. Both patients and FCGs reported multiple comorbidities.

Table 1.

Summary of Patient and Caregiver Demographics (n=18)

| Demographic Characteristic | Patient (n) | Caregiver (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 10 | 14 |

| Male | 8 | 4 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 11 | 18 |

| Did not respond | 7 | 0 |

| Age in yrs | ||

| Less than 50 | 0 | 4 |

| 51–60 | 0 | 5 |

| 61–70 | 7 | 5 |

| 71–79 | 5 | 4 |

| 80 yrs or older | 6 | 0 |

| Cancer diagnosis | ||

| Breast cancer | 2 | 0 |

| Carcinoma | 1 | 0 |

| Prostate cancer | 5 | 0 |

| Brain cancer | 2 | 0 |

| Lung cancer | 3 | 0 |

| Cervical/ovarian | 2 | 0 |

| Lymphoma | 1 | 0 |

| GI (esophageal/ gallbladder) | 2 | 0 |

| Self-Reported Comorbidities | ||

| Heart disease | 1 | 0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 | 0 |

| Lung disease | 1 | 0 |

| Arthritis | 4 | 6 |

| Hypertension | 6 | 0 |

| Other a | 12 | 1 |

Dementia (2), depression (2), seizures, asthma, GERD, mechanical valve, hyperthyroid, renal insufficiency, hypercholesterolemia, hypothyroidism, diverticulitis.

Hospice Nurse Characteristics

Fourteen unique nurses made 18 visits, including four nurses who visited two different FCG-patient dyads. All nurses were female and Caucasian (three nurses indicated mixed race ethnicity); average age of nurses was 45.3 (SD=11.6) years. Thirty-three percent had a Bachelor’s level education, while 66% had an Associate’s degree. Nurses averaged 15.2 years of nursing experience (SD=14.6), and 4.6 years hospice experience (SD=4.4).

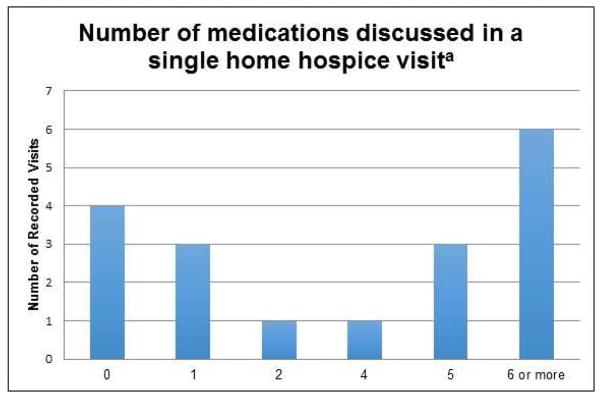

Number and Type of Medications Discussed

The average number of medication names discussed during each home hospice visit was 4.0 (SD 3.5), with a range of 0 to 11 (Fig. 1). The most frequent type of medications discussed were analgesics, followed by laxative/bowel medications and anxiolytics (Table 2).

Fig 1.

Number of Medications Discussed During a Single Home Hospice Visita.

aNote: Generic and brand names of medications were considered as separate medications even if they referred to the same medication.

Table 2.

Summary of Medications Discussed During Home Hospice Visits

| Medication | # of Transcripts |

|---|---|

| Steroids | 4 |

| Pain meds | 20 |

| Anxiolytics | 8 |

| Antipsychotics | 4 |

| Diuretics | 3 |

| Laxatives/Constipation | 10 |

| Appetite/Diet Supplements | 5 |

| Anticoagulants | 2 |

| Antiemetic | 3 |

| Gastric Protection /Digestion | 2 |

| Cardiac | 4 |

| Hypoglycemics | 3 |

| Other endocrine | 3 |

| Antiseizure | 1 |

| Antidepressant | 1 |

| Other symptom management | 2 |

Relationship of Medication Discussions to Lau et al.’s Medication Management Domains

All domains described in Lau et al.’s conceptual framework15 were observed in home hospice visits. We provide definitions and specific exemplars for each domain below (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relationship of Medication Discussions to Lau et al.’s Medication Management Domains15

| Domain | Definition | Subdomain | Exemplar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teamwork Skills | The ability to communicate and coordinate with hospice providers, other family caregivers, and additional hired caregivers. | - | Nurse: Yes, it will ring the hospice main office. So they will answer the phone and I’ll say, < hospice name>, and you will say “My name is G, I need to speak with my nurse please” and they will say, “Okay”. CG: Should we try it? Nurse: No, its okay, that’s the right number. Just know that it won’t be me that answers it. |

| Organizational Skills | The ability to acquire, store, track and discard medications. | - | CG: There is a pharmacy in <city> and they say you have to call in early, so I wondered what you thought about that. Nurse: I think it would be fine, if it is going to save you some money, you know you might as well, what they probably do, they probably send you three month increments, I would have to look at the paperwork to be sure, but that’s probably why you want to do early so they have time for shipping and all that. Pt: So I should have them send me some paperwork. |

| Symptom Knowledge Skills | Ability to recognize and respond to common end-of- life symptoms. | Pain | Nurse: It still hurts? Can you give him just some … Tylenol 3 right? CG: He hasn’t had it but yeah, he had it yesterday. |

| Confusion | Nurse: Because his oxygen is good and I don’t think he is oxygen deprived so it might be a little of dementia just from old age | ||

| Dehydration and dry mouth | |||

| Medication Knowledge Skills | The ability to apply basic pharmacology to medication use. | Understanding medications | CG: She had the long acting and short acting and the Lorazepam because she was so agitated. |

| Educating family caregivers about assessing symptoms and medication | Nurse: That’s good, that medicine I gave you is for your pain but it is going to make your breathing a little bit easier too | ||

| Caregiver worries about medication administration | CG: But I thought I’m either going to give her 2 Ativan or that one but not give her both. (i.e. the Ativan and tramadol)….then I thought ‘Oh my gosh! It is giving her a seizure.’ | ||

| Education and emotional support for administering medications in the final stages of life | Nurse: So that’s how we try to manage those and you can use the atropine at your discretion because it’s really, more so the comfort for the family and anyone is visiting, sometimes it’s really hard to listen to, you can use that again, every hour if needed | ||

| Personhood Skills | The ability to assess the patient’s symptoms and administer medication given the patient’s individual needs, preferences, and ways of communication. | Advocacy for the patient | CG: He had something in the hospital, they told me it was 10 times stronger than morphine – dilaudid. |

| Skills in discontinuing medications | CG: They are 100 mgs, and he takes 4 of them, but I don’t care if they have a 400 mg tab… to give him one… I have 12 of those (to give). Let’s see, I wonder do I continue to do that? | ||

| Advocacy for the family caregiver | PT: That’s what I don’t want, I don’t want for her to get hurt... [that] part is a little frightening…. what would happen if she [the caregiver] falls and couldn’t take care of me, is there a nursing home I would go to? |

Teamwork Skills

The first domain in the framework is teamwork skills, which is defined as the ability to communicate and coordinate with hospice providers, other FCGs, and additional hired caregivers.15 This includes skills such as knowing how and when to contact other team members, and communicating effectively about medication management for pain and symptom control. Teamwork skills and related nurse strategies were observed in 11 of 18 visits. Most frequently, FCGs benefited from nurse facilitation of communication between themselves and other members of the hospice team by providing specific instructions on how, when, and why to call. These included instructions on calling the hospice number at any time with medication- or symptom-related questions and medical emergencies rather than 911. It was also important to establish guidelines and provide concrete instructions about when and how to call. For example, in one instance a nurse had to program the FCG’s cell phone and coach the FCG on how to navigate the on-call coverage system.

We found instances where families were coordinating the administration of medications between different caregivers. In the challenging case of high-risk medications such as insulin, teamwork is critical because of the drug’s narrow therapeutic window and risk for adverse effects such as hypoglycemia. In this circumstance, family members must be able to communicate emergency plans among those sharing responsibility for the patient.

FCG: My sister said [my mother] had one [blood sugar] really low… I had written out very detailed instructions [for my sister]… but I have been taking care of her for so long that I have it in my head… I would have just held off giving her insulin … but [my sister] interpreted that as like have her eat her breakfast and then give it to her …

Coordinating with other medical providers was also an important teamwork skill, particularly since the FCG was often the lynchpin for communicating medication changes and decisions between medical providers. For example, one FCG was responsible for informing the hospice nurse that a medication was discontinued, saying “They discontinued that because she is hardly drinking enough…” Without the FCG, this medication change would not have been directly communicated between the primary care and hospice team.

Organizational Skills

The second domain in the Lau et al. model is organizational skills, which are defined as the ability to acquire, store, track and discard medications15 and include the ability to track insurance coverage and copayment for medications, delivery, and pickup procedures, and order refills. We observed these skills and related nurse strategies in 10 of 18 visits. The most commonly observed skill in this domain focused on the FCG’s responsibility for tracking the administration and timing of symptom control medications such as pain medications.

Nurse: Are we writing down what times we are giving medications?

FCG: I don’t got it written down.

Nurse: I would really like for us to keep a log… it just makes it easier to know exactly what time things are given especially when we are needing to use those as needed medications,…that way we can take a look at exactly how much was given and at what time…then we can say “Oh gosh, you know that I can see that she had this symptom at this time and this is what was done.”

Such tracking was particularly important when mixing both short- and long-acting versions of similar medications. We also saw evidence of FCGs partnering with nurses to be sure they were tracking medications accurately, such as when one FCG instructed another, “Okay, so write down these medications,” to which the nurse further guided the second FCG, “If we need to, … the lorazepam can be given, it said every 6 hours,” upon which the second FCG replies, “Every 6 hours, yeah.”

Apart from medication administration, the FCG also needed organizational skills to keep track of pharmacies and insurance coverage. Unfortunately, different medications come from different pharmacies and it is confusing for patients and FCGs. The hospice “comfort kit” for end-of-life symptom management typically comes from a pharmacy that is different than the patient’s usual pharmacy. For example, “I have the ones in the [hospice comfort] kit plus the other ones,” said one FCG. Mistakes have economic consequences. FCGs typically have to absorb the cost and nurses spend time reversing mistakes:

FCG: …but I still had to pay $24.

Nurse: Oh, no, no, tell them that it’s [a] hospice [medication].

FCG: Yeah, but they put it on there, so I thought is it tax?

Nurse: No, I am going to call them right now and tell them that they need to give you that money back.

Further, medication costs and insurance coverage is highly complex for FGCs and they seek the advice of their nurse about minimizing medication cost.

FCG: There is a pharmacy in <city> and they say you have to call in early, so I wondered what you thought about that.

Nurse: I think it would be fine, if it is going to save you some money, you might as well, what they probably do is send you three month increments. I would have to look at the paperwork to be sure…

Pt: So I should have them send me some paperwork.

Nurse: Sure … if it is going to be cheaper we can definitely look at that. Some of your prescriptions, hospice is going to cover, any of the ones related to your diagnosis, but as far as your diabetic medicine and all of that, it definitely can’t hurt to at least look at the paperwork.

Tracking where medications are kept was another FCG organizational skill needed, particularly if they are being safely stored away for safety from the patient or young children. In one visit the nurse remarked, “I don’t see her new medications at all,” to which the FCG instructs another family member, “Go down and ask … mom keeps putting them up because she doesn’t want them near the baby”. In another visit, the goal was to safely secure medications from confused patients. This is particularly challenging for patients who are normally in control of their medications or are household heads. Dialogue indicated that nurses can adopt the role of establishing rules in order to support the FCG in taking over the medication management role from the patient.

Nurse: I don’t know that any [of the medications] would profoundly hurt you [i.e., the patient], but just to be sure you are safe, always have <FCG’s name> be in charge of that, okay?

FCG: Yup, I’m the pill keeper. So don’t go through the pills….

Nurse: You might want to move them to a different location as well, the pill boxes. When you fill the pill boxes I would put the bottles somewhere else that, I am sorry [patient’s name], not to deceive you, but for your safety…

Symptom Knowledge Skills

The third domain proposed by Lau et al. is symptom-knowledge skills, defined as the ability to recognize and respond to common end-of-life symptoms.15 These skills were found in 12 of the 18 visits. Many symptoms were discussed in the coded home hospice visits, including pain, constipation, confusion, and dry mouth. Each of these symptoms presented specific challenges for FCGs that nurses addressed.

Pain

Adequately controlling pain was a very common issue for FCGs, and this included addressing misinformation about analgesic use. One FCG expressed the misconception that withholding drugs made the medication more effective when given. For example, she said “Another reason I’ve kind of been holding off, when you’re not used to it and when you really, really need it, then it will really work.”

Constipation management was also important for FCGs to understand in the context of opioid use, particularly since many different types of constipation medications were prescribed at the same time (e.g., a stool softener [i.e., Colace], a promotility agent [i.e., Senna] and a liquid agent [i.e., polyethylene glycol]). One FCG said “I can’t give her all of that, I think I counted up all the stool softeners, it was 8 pills, you know … ”. Explanations to FCGs necessitated a description of the various modes of action of the medications. Further, nurses also described what to expect with regard to bowel movements, with statements such as “Don’t worry about no bowel movement for one or two days…” or “We don’t really worry about putting the suppository in until it’s been 2–3 days”. This type of education may be particularly important since these issues can tap into areas of discomfort for family members, and issues of patient dignity, as demonstrated by one FCG saying “Have you ever had a suppository? I have and it is sure uncomfortable.”

FCGs also benefited from being taught about how to assess and manage pain in non-verbal patients. One nurse said “I will go over the signs and symptoms of pain when he can’t tell us, we will look for some of that, so you know how much of the pain medication to give and how often.”

Confusion

Confusion was a particularly difficult symptom for FCGs to manage with medications, since it was often difficult for FCGs to distinguish between dreams, anxiety, dementia, hallucinations, pain, or other causes such as constipation. Nurses are often left trying to help FCGs understand the underlying cause of patient confusion and which drug to use to manage confusion. Choosing the appropriate drug is challenging since different options are provided in the “comfort kit” including antipsychotics and benzodiazepines. This can be very challenging for families. While nurses can provide specific instructions on what to give in the moment, such as, “Okay…what I want us to do right now, she is agitated still and we do have the PRN Haldol, so I would like her to have another tablet of that right now,” families also needed support for when the nurse is not there, as when this FCG asserted, “Okay… but it is 20 times worse in the evening…nothing has helped, its still going on and on.”

Dehydration and Dry Mouth

Realizing that dehydration and symptoms such as dry mouth are common issues as death approaches is helpful for FCGs to understand. Analysis of nurse-FCG communication revealed several strategies to address these issues. Some symptoms can be managed non-pharmacologically and with the use of everyday devices. For patients with difficulty drinking or using bottles, one nurse suggested the use of portable hydration systems such as a Camelbak™. For dry mouth, strategies such as frozen grapes were offered. In another case, discontinuing medications that exacerbate the symptoms was suggested.

Medication Knowledge Skills

The fourth domain in the Lau model is medication knowledge skills, defined as the ability to apply basic pharmacology to medication use,15 such as timing medications to maximum effect, knowing the difference in effects between short-acting/fast-release, and long-acting/extended-release drugs, and the dangers of overdosing. We observed this skill domain in 15 of 18 visits.

Understanding Medications

The number of different medication names discussed in a single visit ranged from 1 to 11 (Fig. 1). Names of medications discussed in the visit can be found in Table 2. Names discussed included both generic and brand names, which can be very confusing for FCGs and patients, and highlights the issue of health literacy as a need for further work.

In addition to managing drug names, FCGs struggle to understand how to safely administer multiple drugs with synergistic effects, and how to avoid undesirable drug combinations. FCGs also needed education about medications’ desired and expected effects, as well as undesired and adverse effects. We also found instances of nurses discussing how some medications will make patients feel better, but also noted potential downsides. One nurse said, “The steroids help with just feeling good”, but later added that they may also “cause fluid retention in the legs.” Such mixed messages can be difficult for families to absorb.

Further complicating the issue of medication administration is FCGs’ difficulty in understanding differences between liquid and pill forms. Some medications can be given in either liquid or pill forms (e.g., haloperidol, some opioids), with implications for ease of administration and speed of onset, but this can be confusing.

Nurse: So you can use the liquid oxycodone if you have that pain because the liquid works a lot faster than the tablet so if you need a little extra something you can use the liquid. Okay? And you can use it with the hydrocodone [pills].

FCG: I can?

There is even more confusion when a medication comes in different forms and has similar dosages for each form. Some nurses tried to explain between liquid and pill forms based on the FCG’s comfort.

Nurse: It’s the same dose as the pill…if you give him half of the syringe it’s the same as one pill.

FCG: We haven’t used those at all.

Nurse: Okay, [use] whatever you are more comfortable with.

There is even further confusion when a single medication can address multiple symptoms. The classic example is opioids, for which education is particularly important.20 FCGs learned that opioids help with both pain and shortness of breath: “That’s good, that medicine I gave him is for his pain but it is going to make his breathing a little bit easier too.”

“As needed” medications are particularly challenging, as the pill bottles will have specific instructions that provide a range of times for administration, timing that the nurse can often override. For example, in one visit, the nurse gave specific instructions that differed from the prescription bottle, “I’ve written down every six hours [but] you can actually give it every hour until he is calm.”

FCG Worries about Medication Administration

FCGs worried about harming their family members and showed uncertainty in administering medications. One FCG expressed, “But I thought I’m either going to give her two Ativan or that one but not give her both. (i.e., the Ativan and tramadol)….then I thought ‘Oh my gosh! It is giving her a seizure’.”

Most FCGs are also new to administering liquid medications, including how to measure in a syringe and how to use a dropper, common practices in hospice. FCGs do not want to make mistakes. In the example below, the nurse reassured and educated the family about use of the syringe and the dropper.

Nurse: As far as the bubble goes, don’t worry because it’s not an IV.

FCG: Well, that’s what I was measuring (i.e., the bubble).

Nurse: …and if you go over, it’s not going to hurt him.

FCG: I spend a lot of time trying to get the exact.

Nurse: Don’t worry about that, just get it close and it will be fine.

FCGs are very concerned about timing and dosage. They first tended to adhere to directions on the label, but then learned that some medications can be given early. In admitting a mistake, one FCG was worried because “I gave…both the methadone and oxycodone even though it was 2 hours early,” to which the nurse replied, “That’s okay…. We will increase the frequency until he gets a little more comfortable.”

Education and Emotional Support for Administering Medications in the Final Stages of Life

At the very end of life, rapidly changing patient symptoms take a heavy emotional toll on FCGs. During this stage, FCGs often needed detailed information and emotional support. For example, in one visit a FCG asks the nurse which medication the nurse would prefer to administer first to address terminal agitation. The nurse offered “Between the lorazepam and Haldol? Uh you know for just right now, I would give them together, just so that we can get him back comfortable.”

Easing family members’ distress with a patient’s symptoms was also essential. One nurse explained to the FCG the reason for administering atropine for the patient’s airway secretions, “So that’s how we try to manage those, and you can use the atropine at your discretion because it’s really, more so the comfort for the family and anyone [who] is visiting, sometimes it’s really hard to listen to, you can use that again, every hour if needed.”

Personhood Skills

The final domain in the Lau model of medication skills for hospice is personhood skills, defined as the ability to assess the patient’s symptoms and administer medication given the patient’s individual needs, preferences, and ways of communication.13 We observed this in 10 of 18 visits. We mostly observed evidence of advocacy for patients’ desires and distaste for medications.

FCGs commonly advocated for medications that the patient wanted to take, such as medications that have worked for the patient in the past. For example, after trying some oxycodone with inadequate relief, the FCG reported to the nurse that Dilaudid had worked for the patient in the past, and this led to a medication change.

FCGs also advocated for medications that the patient did not want to take and for reductions in overall pill burden. In the example below, the FCG’s concern is met with the concession that the medication is no longer necessary.

FCG: They are 100 mgs, and he takes 4 of them, but I don’t care if they have a 400 mg tab… to give him one… I have 12 of those (to give). Let’s see, I wonder, do I continue to do that?

Nurse: I talked to Dr. <name of physician> and he said that you don’t really need to do this one anymore.

We also found FCGs struggling with whether to share that patients were not adhering to the medication regimen. In this quote, the daughter and nurse have stepped out of the patient’s room and the daughter shares her frustration about her mother refusing to take her medication, “She just does whatever she feels like she is going to do.”

Interestingly, we also observed a need for advocacy for the FCG to take over medication control from the patient, particularly when patients were losing cognitive ability. We observed several cases. In one instance involving chronic anticoagulation therapy that the patient had self-managed for years, the FCG was aware of the medication dosing and blood monitoring requirements, but the patient was not ready to let go of control. The FCG stated to the nurse, “He’s always done that himself and I just wasn’t sure”. In this case, there is a need for skillful inclusion of the patient as a team member in the transition, maintenance of the patient’s autonomy and dignity, but with recognition of the patient’s growing inability to self-manage medications.

Discussion

This study provides an in-depth examination of FCG-nurse communication about medication management in home hospice visits. A key objective was to map previously identified domains of FCG skill needs for medication management15 to actual home hospice visits with nurses. The original domains were developed from stakeholder interviews, rather than from recorded visits, and we found strong evidence of their validity in actual hospice visits. Further, we gained insight into specific examples of FCG needs for pain and symptom management medication skills within each of Lau’s five domains. Our findings highlight the many levels of uncertainty for FCGs, and the many challenges facing nurses regarding pain and symptom management for home hospice. Our unique and rich recordings of home hospice visits provide critical knowledge about the medication skills required by hospice FCGs for successful medication management.

FCG Medication Management Needs

Our findings illustrate the specific ways that FCGs need support in the home hospice setting to use medications to manage pain and symptoms. First, patient and family education about pain and symptom management requires promoting teamwork with hospice, other medical providers, and other informal caregivers. FCGs specifically need to know how to access hospice support and how to share and communicate medication management responsibilities with other team members. Second, FCGs need organizational skills to track correct medication acquisition, payment, and administration. Third, FCGs needed help understanding pain and common symptoms in order to effectively use the appropriate medications. A key skill is learning how to recognize major clinical status changes, including typical disease progression and the type of care expected. While some visits had very little symptom management, just focusing on medication refills and quantity check, other visits focused on pain and at least one or more symptoms, including constipation, confusion, sleep, agitation, edema, and dry mouth. This was critical since the ability of FCGs to provide pain and symptom relief to their ill-family members is recognized as affecting FCG emotions and wellbeing.12, 14

Beyond teamwork, organization, and symptom knowledge skills, FCGs also needed support to gain critical medication knowledge skills beyond the topics of safety and administration. Distinguishing drug names, the difference between liquid and pills forms, and avoiding undesirable drug combinations were complicated and frequent issues. While this is all second nature to clinicians, it is very challenging and complicated for FCGs. Even learning the indications for, and benefits and side effects of drugs can be complicated. Take the case of benzodiazepines that are commonly used in hospice. On the one hand, the drug is used to treat agitation; on the other hand, the undesired effect is increased agitation. It can be confusing trying to explain this to FCGs. Finally, under medication knowledge, we found that it was also important to explain that some medications such as atropine were very helpful to ease family members’ distress such as in terminal secretions.

Finally, under the fifth Lau et al. domain of personhood, FCGs skills and needs also included the need to advocate and consider the patient’s personhood into the medication management strategy. Sometimes this meant advocating for certain medications, other times it meant discontinuing medications, and yet other times it meant taking over control of medication administration and dosing from the patient.

FCG Behaviors

FCG emotion and stress were evident across all visits and impacting all skill domains. Often FCGs showed eagerness “to do it right” while also expressing anxiety about giving too much or too little medication or giving it at the wrong time. Furthermore, consistent with other research about FCGs’ reluctance to voice concerns,21–22 we found they were at times uncertain about what to say and with whom to communicate about medication issues. Previous literature has documented the negative effect FCG uncertainty and stress can have on management of patient symptoms23, 24 and that both patients and FCGs worry about pain.2,25

Our findings also reveal that FCGs are not just passive recipients of information, but were active in trying to understand and anticipate symptoms, and in problem solving. Many FCGs had extensive knowledge about patient responses to medications and spoke up about a patient’s response to a specific medication. There were instances of nurses being able to rely on FCGs’ documentation of medication and symptom response and on information regarding other provider medications. Engaged and activated FCG skills are necessary for effective symptom and medication management as well as general patient care.26 This is especially important in communicating with their hospice nurses. When FCGs talk openly about chief concerns, nurses gain an enhanced understanding and the likelihood of addressing family needs is increased.

Our study used, for the first time, actual home hospice visits to validate stakeholder- identified medication management domains. The recorded conversations showed instances of FCGs exhibiting medication management behaviors and of nurses facilitating FCGs in the numerous complexities of managing medications for a dying patient. However, this study also clearly indicated areas where nurses could provide more specific and useful coaching to overwhelmed and stressed FCGs. To date, most symptom management training for cancer FCGs in homecare has focused on non-pharmacological support.27 Our study, although conducted in a small sample, demonstrates that interventions to increase support for FCG medication management are urgently needed.

Strategies to Support Family Caregivers

A strength of our study was that we were able to identify specific examples of interventions that supported FCG medication management skills.. We also saw multiple opportunities where the hospice team might improve their coaching of FCGs.

Nurses’ discussion of medication management across all of the identified domains occurred at a basic level. They frequently failed to operationalize skills in such a way that busy and overwhelmed FCGs can actively use and problem solve based on their skill acquisition. For example, in the teamwork domain, even though nurses expressed that the hospice team was readily available to answer any questions, rarely were explanations given about how to reach staff, which staff member would be available, and how FCGs could raise their questions and concerns so as to be heard. Additionally, in some cases, nurses encouraged the family to log medications, yet provided little to no instruction on how to record symptoms, dosage, timing and symptom response, let alone alert other FCGs to participate in documentation.

Similar to other studies, we found instances where nurses tried to reassure and present more in-depth information about specific symptoms and the related medication.14, 27 We also found examples of nurses tailoring medication information to family and patient needs, particularly in preparing them for what to expect next. Nurses helped FCGs anticipate the patient’s symptom course as well helped FCGs anticipate their own emotional response to providing medications and subsequent patient response. Finally, we found evidence of nurses accompanying explanations of end-of-life medication provision with emotional support.

Nurse use of reassurance, emotional support, provision of tailored, in-depth information and anticipatory guidance are all likely to be helpful to busy FCGs. However, what was largely missing from the recorded visits was evidence of nurses breaking down information into understandable components, using repetition, asking for understanding, or engaging in teach back.28, 29 These strategies are likely to be effective for individuals in cognitive and emotional overload, a state which most family FCGs face. Lau et al. discuss symptom and medication knowledge (e.g., “understanding time to peak effectiveness”), but our findings indicate that both hospice nurses and families need basic tools to help FCGs assimilate the information so they can gain competency.

Since this study focuses on hospice nurse-caregiver interactions, these interventions were delivered by hospice nurses. However, many of these interventions could be integrated into the responsibilities of the larger hospice interdisciplinary team who may become aware of caregivers’ problems with medication management. Indeed, one prior study documented substantial interdisciplinary involvement in medication management issues for FCGs, including social workers, physicians, and chaplains.13

Limitations

Although the sample size of this study is appropriate for the qualitative analysis we conducted,30 it is relatively small and is derived from one region of the U.S. All patients were diagnosed with cancer and thus the medication issues our study highlights may not be relevant for other conditions. Additionally, we analyzed only one home hospice visit per case. The average number of home hospice visits by a nurse for these cases was 18.4, but the range was one to 93. Since duration of hospice enrollment varied, some of the recorded visits were early in the hospice course, and some were late in the hospice course (including very near death), thus allowing for some inclusion of disease severity variation in the sample case mix. However, ongoing work is examining changes in medication-related visit content over time and is outside the scope of the current study. Since FCG issues may vary over time as the FCG gains confidence, future research is needed to understand how skills can be built from visit to visit. Despite these limitations, our data is in-depth, rich and largely maps onto other findings from others.15, 31

Summary and Conclusions

There are no clinical guidelines to help hospices and the families they serve with medication management.14 Our clinically based findings support the need for further education of hospice providers in teaching medication management skills. Our study advances Lau et al.’s and others’ foundational work by providing clinical validation and expansion of specific skill domains for effective FCG medication management of hospice patient symptoms. We provided actual clinical exemplars, which give insight into the interventions that are needed to help hospice providers and FCGs. Further, our findings suggest that FCGs, patients and providers need to upstream these skills so that families have a schema for medication management prior to transitioning to the stressors of end of life.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (P01-CA138317) from the National Cancer Institute. Drs. Ellington (P01 Project Leader), Clayton and Reblin were supported by this grant. Dr. Tjia was supported by a grant (PEP-11-263-01-PCSM) from the American Cancer Society New England Division – Ellison Foundation.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patients, family caregivers and nurses who participated in this research and the research team who supported this work. We also thank Djin Lai, BSN, RN, for her careful work on this manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no potential personal or financial conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hauser JM, Kramer BJ. Family caregivers in palliative care. Clin Geriatr Med. 2004;20:671–688. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kutner J, Kilbourn KM, Costenaro A, et al. Support needs of informal hospice caregivers: a qualitative study. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:1101–1104. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGuire DB, Grant M, Park J. Palliative care and end of life: the caregiver. Nurs Outlook. 2012;60:351–356. e320. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau DT, Berman R, Halpern L, et al. Exploring factors that influence informal caregiving in medication management for home hospice patients. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:1085–1090. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donelan K, Hill CA, Hoffman C, et al. Challenged to care: informal caregivers in a changing health system. Health Affair. 2002;21:222–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.4.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glajchen M. The emerging role and needs of family caregivers in cancer care. J Support Oncol. 2003;2:145–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang SS, Chang VT, Alejandro Y, et al. Caregiver unmet needs, burden, and satisfaction in symptomatic advanced cancer patients at a Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center. Palliat Support Care. 2003;1:319–329. doi: 10.1017/s1478951503030475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osse BH, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Schadé E, Grol RP. Problems experienced by the informal caregivers of cancer patients and their needs for support. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29:378–388. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200609000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schumacher KL, Stewart BJ, Archbold PG, et al. Effects of caregiving demand, mutuality, and preparedness on family caregiver outcomes during cancer treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:49–56. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.49-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paice JA, Muir JC, Shott S. Palliative care at the end of life: comparing quality in diverse settings. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2004;21:19–27. doi: 10.1177/104990910402100107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joyce BT, Berman R, Lau DT. Formal and informal support of family caregivers managing medications for patients who receive end-of-life care at home: a cross-sectional survey of caregivers. Palliat Med. 2014;28:1146–1155. doi: 10.1177/0269216314535963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliver DP, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Washington K, et al. Hospice caregivers’ experiences with pain management: “I’m not a doctor, and i don’t know if i helped her go faster or slower”. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:846–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joyce BT, Lau DT. Hospice experiences and approaches to support and assess family caregivers in managing medications for home hospice patients: a providers survey. Palliat Med. 2012;27:329–338. doi: 10.1177/0269216312465650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau DT, Joyce B, Clayman ML, et al. Hospice providers’ key approaches to support informal caregivers in managing medications for patients in private residences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:1060–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lau DT, Kasper JD, Hauser JM, et al. Family caregiver skills in medication management for hospice patients: a qualitative study to define a construct. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64:799–807. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellington L, Reblin M, Clayton MF, Berry P, Mooney K. Hospice nurse communication with cancer patients and their family caregivers. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:262–268. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guest G, Bunce A, Jonson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mcmillan SC. Interventions to facilitate family caregiving at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(Suppl 1):s-132–s-139. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.s-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Wever LD, et al. The patient-physician relationship. Patient-physician communication during outpatient palliative treatment visits: an observational study. JAMA. 2001;285:1351–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.10.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1013–1025. doi: 10.1002/pon.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keefe FJ, Lipkus I, Lefebvre JC, et al. The social context of gastrointestinal cancer pain: a preliminary study examining the relation of patient pain catastrophizing to patient perceptions of social support and caregiver stress and negative responses. Pain. 2003;103:151–156. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00447-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Northouse L, Williams A-l, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimberlin C, Brushwood D, Allen W, Radson E, Wilson D. Cancer patient and caregiver experiences: communication and pain management issues. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:566–578. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolff JL, Roter DL, Given B, Gitlin LN. Optimizing patient and family involvement in geriatric home care. J Healthc Qual. 2009;31:24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2009.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hendrix CC, Abernethy A, Sloane R, Misuraca J, Moore J. A pilot study on the influence of an individualized and experiential training on cancer caregiver’s self-efficacy in home care and symptom management. Home Healthc Nurse. 2009;27:271–278. doi: 10.1097/01.nhh.0000356777.70503.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheehy-Skeffington B, McLean S, Bramwell M, O’Leary N, O’Gorman A. Caregivers experiences of managing medications for palliative care patients at the end of life a qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31:148–154. doi: 10.1177/1049909113482514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wittenberg-Lyles E, Oliver DP, Kruse RL, et al. Family caregiver participation in hospice interdisciplinary team meetings: how does it affect the nature and content of communication? Health Commun. 2013;28:110–118. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.652935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18:179–183. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schumacher KL, Plano Clark VL, West CM, et al. Pain medication management processes used by oncology outpatienst and family caregivers, part I: health system contexts. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48:770–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.12.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]