Abstract

Introduction

TV viewing is the most prevalent sedentary behavior and is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality, but the association with other leading causes of death is unknown. This study examined the association between TV viewing and leading causes of death in the U.S.

Methods

A prospective cohort of 221,426 individuals (57% male) aged 50–71 years who were free of chronic disease at baseline (1995–1996), 93% white, with an average BMI of 26.7 (SD=4.4) kg/m2 were included. Participants self-reported TV viewing at baseline and were followed until death or December 31, 2011. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for TV viewing and cause-specific mortality were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression. Analyses were conducted in 2014–2015.

Results

After an average follow-up of 14.1 years, adjusted mortality risk for a 2-hour/day increase in TV viewing was significantly higher for the following causes of death (HR [95% CI]): cancer (1.07 [1.03, 1.11); heart disease (1.23 [1.17, 1.29]); chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (1.28 [1.14, 1.43]); diabetes (1.56 [1.33, 1.83]); influenza/pneumonia (1.24 [1.02, 1.50]); Parkinson disease (1.35 [1.11, 1.65]); liver disease (1.33 [1.05, 1.67]); and suicide (1.43 [1.10, 1.85]. Mortality associations persisted in stratified analyses with important potential confounders, reducing causation concerns.

Conclusions

This study shows the breadth of mortality outcomes associated with prolonged TV viewing, and identifies novel associations for several leading causes of death. TV viewing is a prevalent discretionary behavior that may be a more important target for public health intervention than previously recognized.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00340015

Introduction

TV viewing is the most prevalent leisure-time behavior in the U.S. and an estimated 289 million Americans (92%) have a TV at home.1 On a given day, 80% of American adults watch TV for an average of 3.5 hours per day, which is more than half (55%) of their available leisure time.2 In the past 10 years, a growing body of evidence has linked prolonged TV viewing to poor health. A 2011 meta-analysis showed that each 2-hour increase in TV viewing was associated with a 13% increased risk of all-cause mortality.3

To date, TV viewing and mortality studies have focused on the two leading causes of death, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer, which account for only half of all deaths in the U.S.4,5 TV viewing has consistently been linked with increased risk of CVD mortality,4–8 even among individuals exceeding current recommendations for moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA).5 Associations with cancer mortality have been less consistent.4–7 Whether TV viewing is associated with causes of death other than CVD and cancer is not yet established. The displacement of physical activity by prolonged TV viewing has been hypothesized to explain the positive association between TV and diabetes and cardiometabolic biomarkers.9–11 TV viewing has also been prospectively associated with poor mental health12 and depression.13,14 Quite plausibly, TV viewing may be linked to other leading causes of death, though this has not, to our knowledge, been examined.

The present study examined the association between TV viewing and the leading causes of death in the U.S. A better understanding of the causes of death associated with prolonged TV viewing may suggest new hypotheses related to the deleterious health effects of sedentary behavior and may help inform future public health recommendations.

Methods

The NIH-AARP Health Study (ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00340015) has been described previously.15 In 1995–1996, 3.5 million AARP members aged 50–71 years who lived in one of six states (California, Florida, Louisiana, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania) or two metropolitan areas (Atlanta, Georgia and Detroit, Michigan) were mailed a questionnaire asking about their medical history, diet, and demographic characteristics. Of the 566,401 participants who initially responded, those who did not report colon, breast, or prostate cancer were asked to complete a second questionnaire 6 months later that asked about TV viewing and other health behaviors. Completion of the questionnaires was considered to imply informed consent. The Special Studies IRB of the U.S. National Cancer Institute approved the study.

Eligible participants were those who responded to both questionnaires, were alive, and had not moved from the study area before returning the second questionnaire (N=334,921). Those who indicated they were proxies for the intended respondents (n=10,383); a prior history of cancer (n=18,863), heart disease or stroke (n=45,752), or emphysema (n=5,709); missing or extreme BMI values (≤18.5 or ≥60 kg/m2; n=7,874); missing TV viewing or MVPA (n=4,103); or had extreme log-transformed energy intake values (n=1,844) were excluded. To further address reverse causation concerns we eliminated those who reported “poor” or “fair” health (n=18,951), resulting in a final analytic cohort of 221,426.

Exposure Assessment

TV viewing was assessed using a questionnaire that asked: During a typical 24-hour period over the past 12 months, how much time did you spend watching television or videos? Responses were categorized as 0–1, 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, and ≥7 hours/day. Validity of this question has not been evaluated, but it is similar to questions that have acceptable validity compared to behavioral logs (r =0.61)16 and an electronic TV monitor (r =0.51).17

Mortality Outcomes

Follow-up of participants was completed via annual linkage to the U.S. Postal Service’s National Change of Address database, through processing undeliverable mail, using address change services, as well as participant notifications. Vital status ascertainment was performed by annual linkage of the cohort to the Social Security Administration Death Master File. Verification of vital status and cause of death were obtained by searches of the National Death Index (NDI) Plus and was available for >95% of the cohort.

We categorized the leading causes of death in the U.S. using the same classification approach employed by the National Center for Health Statistics for vital status reporting18 based on the causes of death provided by the NDI. The specific ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes used to classify each outcome are provided in Appendix Table 1: malignant neoplasms (cancer); diseases of the heart (CHD); chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and allied conditions (COPD); cerebrovascular disease (stroke); accidents and adverse effects (accidents); Alzheimer disease; diabetes mellitus (diabetes); nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrosis (kidney disease); influenza and pneumonia; intentional self-harm (suicide); septicemia (sepsis); chronic liver disease and cirrhosis (liver disease); essential hypertension and hypertensive renal disease (hypertension); and Parkinson disease.

Covariates

Numerous self-reported covariates were evaluated as potential confounders and are listed and defined in Table 1. Diet was assessed using a 124-item food frequency questionnaire,19 and the Healthy Eating Index 2005 (HEI-2005) was used as a measure of overall diet quality.20

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics according to TV viewing category: among 221,426 participants at baseline: NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study

| TV viewing category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 h/d | 1–2h/d | 3–4h/d | 5–6h/d | ≥7 h/d | |

| N | 16,798 | 67,657 | 97,255 | 30,791 | 8,925 |

| Age (yrs) | 60.8 ± 5.4 | 61.9 ± 5.4 | 62.8 ± 5.3 | 63.5 ± 5.1 | 63.2 ± 5.2 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.3 ± 4.0 | 26.2 ± 4.1 | 26.9 ± 4.4 | 27.6 ± 4.8 | 28.2 ± 5.3 |

| Female (%) | 47 | 41 | 42 | 46 | 52 |

| White (%) | 95 | 94 | 93 | 92 | 88 |

| Black (%) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 |

| Some college or college graduate (%) | 84 | 75 | 64 | 55 | 47 |

| Married or living as married (%) | 66 | 71 | 70 | 65 | 58 |

| Obesity, BMI >30, (%) | 11 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 |

| Current smoker (%) | 6 | 8 | 11 | 14 | 18 |

| Dietary intake | |||||

| Calories (kcal/day) | 1739.8 ± 702 | 1779 ± 737 | 1820 ± 761 | 1875 ± 817 | 1931 ± 900 |

| Alcohol intake (g/day) | 11.0 ± 24.2 | 12.3 ± 28.5 | 12.8 ± 30.6 | 13.3 ± 34.2 | 13.6 ± 38.9 |

| HEI-2005 total score | 69.7 ± 10.4 | 68.3 ± 10.8 | 66.9 ± 11.2 | 65.3 ± 11.7 | 64.1 ± 12.2 |

| Physical activity and sleep (%) | |||||

| MVPA >7h/wk | 30 | 32 | 27 | 26 | 24 |

| Sleep <7 h/day | 30 | 32 | 33 | 36 | 41 |

| Health status at baseline (%) | |||||

| Excellent | 38 | 27 | 20 | 16 | 14 |

| Hypertension | 25 | 31 | 35 | 39 | 42 |

| High cholesterol | 56 | 51 | 47 | 44 | 43 |

| Diabetes | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 |

| Bone fracture after 45y | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Osteoporosis | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

Statistical Analysis

Covariates that changed the magnitude of associations by at least 10% with all-cause mortality were retained in the fully adjusted models.

Model 1 adjusted for age (years), sex (male or female), race (white, black, other, or missing), education (<12 years, high school graduate, some college, college graduate, or missing), smoking history (never; quit, ≤20 cigarettes/day; quit, >20 cigarettes/day; current, ≤20 cigarettes/day; current, >20 cigarettes/day; or missing), and diet quality (HEI-2005 score quintiles) and MVPA (never or rarely, 1, 1–3, 4–7, or ≥7 hours/week).

Model 2 included covariates from Model 1 plus two variables that may could be considered confounders or potential causal intermediaries between TV viewing and morality: BMI (18.5–<25, 25–<30, 30–35, or >35 kg/m2) and self-reported health status (good, very good, or excellent).

For each of the mortality outcomes, Cox proportional hazards regression was used to obtain the adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for each of the five categories of TV viewing using the lowest category as the referent. Given the higher proportion of the population in the 1–2 hour/day category, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with that group as the referent. To test for linear trend, we translated the categorical responses to hours/day using the midpoints of the duration interval indicated for each response option. We then divided these values by two and employed this version of the response as a continuous variable in our models. The regression coefficients were then in units that are interpreted as a 2-hour/day increase in risk. The underlying time variable was calculated from the scan date on the second questionnaire until death from any cause or the end of the follow-up on December 31, 2011. The proportional hazards assumption was tested by examining the interaction between follow-up time and TV viewing.

Additional analyses examined effect modification of TV viewing by strata of sex, age quartiles, BMI, education, MVPA, diet quality, smoking, marital status, diabetes, hypertension, cholesterol, and health status for the 11 other causes of death (excluding CVD and cancer). To assess whether the associations for TV and mortality persisted in physically active individuals, multiplicative interactions for MVPA (active ≥4 hours/week and inactive <4 hours/week) and TV viewing (low, <2 hours/day; medium, 3–4 hours/day, and high, >5 hours/day) and joint effects by setting a common referent group (i.e., low TV and active) were performed. Statistical significance of the interactions for subgroups and activity status were assessed using likelihood ratio tests comparing Cox proportional hazards models with and without cross-product terms for each level of the baseline stratifying variable, with TV viewing as a continuous variable. Sensitivity analyses were completed excluding deaths in the first 3 years of follow-up and among never smokers. SAS, version 9.3 was used for all analyses and statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Analyses were conducted in 2014–2015.

Results

At baseline, those who watched more TV were less likely to have attended college, sleep at least 7 hours/night, or have high cholesterol. Higher TV viewers tended to consume more calories and alcohol, were more likely to be obese (BMI >30 kg/m2), smokers, and have diabetes or hypertension (Table 1). The Spearman correlation between TV viewing (hours/day) and MVPA (hours/week) was 0.06. During a mean of 14.1 (SD=2.2) years of follow-up, there were 36,590 deaths (Table 2). All-cause mortality risk was increased by 14% per 2-hour/day increase in TV viewing (p<0.001). The average age of death for <1 hour/day (73.9 [SD=6.4] years) was similar to the >7 hours/day category (74.8 [SD=6.0] years). There was a modest violation of the proportional hazards assumption, indicating a difference in the association between TV viewing and all-cause mortality at different follow-up times, although risk was significantly elevated at both time points (p<0.001). The deviation occurred at 6 years of follow-up, with risk estimates <6 years of (HR [95% CI]) 1.21 (1.16, 1.28) and for ≥6 years of 1.12 (1.09, 1.15). Additional information is found in the Appendix.

Table 2.

Association of TV viewing and cause-specific mortality: NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study.

| Television viewing (h/day) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 1–2 | 3–4 | 5–6 | >7 | P for trend | |||

| All Participants (N) | 17,035 | 68,281 | 97,993 | 31,003 | 8,990 | |||

| All causes | No. of deaths | 36,590 | 1,851 | 9,368 | 16,722 | 6,452 | 2,197 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 1.06 (1.00, 1.11) | 1.15 (1.09, 1.20) | 1.25 (1.19, 1.32) | 1.47 (1.38, 1.56) | <0.001 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.14) | 1.15 (1.09, 1.21) | 1.33 (1.25, 1.41) | <0.001 | ||

| Cancer | No. of deaths | 15,161 | 854 | 4026 | 6933 | 2555 | 793 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 1.05 (0.98, 1.13) | 1.10 (1.02, 1.19) | 1.17 (1.06, 1.29) | <0.001 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 0.98 (0.91, 1.06) | 1.03 (0.96, 1.10) | 1.06 (0.98, 1.15) | 1.12 (1.02, 1.24) | <0.01 | ||

| CHD | No. of deaths | 7,340 | 319 | 1805 | 3374 | 1328 | 514 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 1.17 (1.04, 1.32) | 1.33 (1.19, 1.50) | 1.50 (1.32, 1.69) | 2.02 (1.75, 2.33) | <0.001 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 1.09 (0.97, 1.23) | 1.19 (1.06, 1.33) | 1.26 (1.11, 1.43) | 1.64 (1.42, 1.90) | <0.001 | ||

| Stroke | No. of deaths | 1,748 | 100 | 461 | 792 | 310 | 85 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.97 (0.78, 1.20) | 1.01 (0.81, 1.24) | 1.10 (0.87, 1.38) | 1.04 (0.78, 1.40) | 0.19 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 0.94 (0.76, 1.17) | 0.96 (0.78, 1.19) | 1.03 (0.82, 1.30) | 0.97 (0.72, 1.30) | 0.54 | ||

| COPD | No. of deaths | 1,522 | 49 | 304 | 706 | 341 | 122 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 1.13 (0.84, 1.53) | 1.35 (1.01, 1.81) | 1.55 (1.15, 2.10) | 1.72 (1.23, 2.41) | <0.001 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 1.08 (0.80, 1.46) | 1.26 (0.94, 1.68) | 1.42 (1.05, 1.92) | 1.54 (1.10, 2.16) | <0.001 | ||

| Accidents | No. of deaths | 919 | 61 | 276 | 390 | 152 | 40 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.97 (0.74, 1.28) | 0.87 (0.66, 1.15) | 1.02 (0.75, 1.38) | 0.98 (0.65, 1.47) | 0.95 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 0.97 (0.71, 1.31) | 0.97 (0.70, 1.36) | 1.12 (0.75, 1.67) | 1.01 (0.62, 1.64) | 0.62 | ||

| Alzheimer disease | No. of deaths | 796 | 36 | 235 | 354 | 136 | 35 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 1.36 (0.96, 1.94) | 1.27 (0.90, 1.80) | 1.43 (0.99, 2.08) | 1.39 (0.87, 2.23) | 0.27 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 1.37 (0.97, 1.95) | 1.29 (0.91, 1.83) | 1.48 (1.01, 2.15) | 1.46 (0.91, 2.34) | 0.17 | ||

| Diabetes | No. of deaths | 767 | 30 | 138 | 365 | 164 | 70 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.98 (0.66, 1.45) | 1.59 (1.09, 2.32) | 2.05 (1.38, 3.04) | 2.95 (1.91, 4.57) | <0.001 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 0.84 (0.57, 1.25) | 1.24 (0.85, 1.80) | 1.41 (0.95, 2.10) | 1.93 (1.24, 2.98) | <0.001 | ||

| Influenza/pneumonia | No. of deaths | 550 | 22 | 149 | 244 | 92 | 43 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 1.36 (0.87, 2.12) | 1.33 (0.86, 2.06) | 1.42 (0.89, 2.28) | 2.41 (1.43, 4.06) | 0.01 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 1.30 (0.83, 2.04) | 1.25 (0.80, 1.94) | 1.30 (0.81, 2.10) | 2.18 (1.29, 3.69) | 0.03 | ||

| Parkinson disease | No. of deaths | 513 | 29 | 125 | 252 | 79 | 28 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.91 (0.60, 1.36) | 1.19 (0.81, 1.76) | 1.17 (0.76, 1.80) | 1.70 (1.00, 2.88) | 0.01 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 0.92 (0.61, 1.38) | 1.22 (0.83, 1.81) | 1.21 (0.78, 1.87) | 1.77 (1.04, 3.02) | 0.00 | ||

| Kidney disease | No. of deaths | 429 | 22 | 87 | 210 | 76 | 34 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 0.78 (0.49, 1.25) | 1.08 (0.69, 1.68) | 1.04 (0.64, 1.69) | 1.54 (0.89, 2.66) | 0.01 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 0.72 (0.45, 1.15) | 0.94 (0.60, 1.47) | 0.85 (0.52, 1.38) | 1.22 (0.70, 2.11) | 0.13 | ||

| Sepsis | No. of deaths | 395 | 13 | 86 | 198 | 68 | 30 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 1.33 (0.74, 2.38) | 1.76 (1.00, 3.11) | 1.64 (0.90, 3.00) | 2.40 (1.24, 4.66) | <0.01 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 1.23 (0.68, 2.20) | 1.53 (0.87, 2.70) | 1.32 (0.72, 2.42) | 1.85 (0.95, 3.59) | 0.09 | ||

| Liver disease | No. of deaths | 374 | 19 | 92 | 159 | 75 | 29 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 1.04 (0.63, 1.70) | 1.12 (0.69, 1.81) | 1.52 (0.91, 2.54) | 2.04 (1.13, 3.67) | <0.01 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 0.96 (0.59, 1.58) | 0.99 (0.61, 1.60) | 1.27 (0.76, 2.13) | 1.65 (0.91, 2.99) | 0.02 | ||

| Suicide | No. of deaths | 292 | 14 | 70 | 140 | 55 | 13 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 1.07 (0.60, 1.91) | 1.40 (0.80, 2.44) | 1.70 (0.93, 3.09) | 1.48 (0.69, 3.18) | 0.01 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 1.10 (0.62, 1.96) | 1.46 (0.83, 2.55) | 1.79 (0.98, 3.27) | 1.55 (0.72, 3.36) | 0.01 | ||

| Hypertension | No. of deaths | 267 | 12 | 63 | 121 | 56 | 15 | |

| Model 1 | ref | 1.13 (0.61, 2.09) | 1.31 (0.72, 2.39) | 1.67 (0.89, 3.16) | 1.52 (0.70, 3.29) | 0.03 | ||

| Model 2 | ref | 1.04 (0.56, 1.93) | 1.14 (0.62, 2.08) | 1.38 (0.73, 2.62) | 1.22 (0.56, 2.65) | 0.18 | ||

Note: Values are Hazard Ratio (95% CI). P for trend was determined by entering the midpoint of each category a model as a continuous variable.

Model 1 was adjusted for age (yrs), sex, race (white, black, other, missing), education (<12 yrs, high school graduate, some college, college graduate, missing), smoking history (never; quit, ≤20 cigarettes/day; quit, >20 cigarettes/day; current, ≤20 cigarettes/day; current, >20 cigarettes/day; unknown), MVPA (never or rarely, 1, 1–3, 4–7, ≥7 h/wk) and diet quality (quintiles).

Model 2 was adjusted for the above plus BMI categories (18.5 to <25, 25–<30, 30–35 and >35 kg/m2) and health status (good, very good, excellent)

Association of TV Viewing With Leading Causes of Death

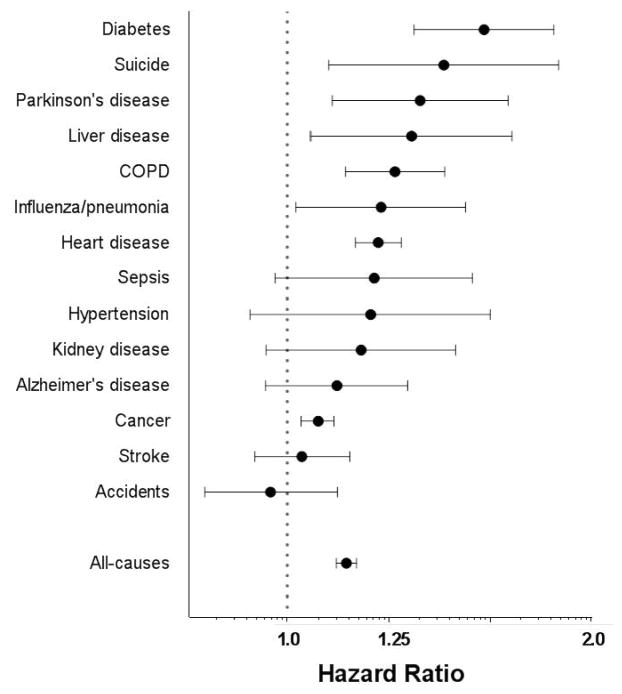

When examined on a continuous basis, each 2-hour/day increase in TV viewing was significantly associated with an increased risk of mortality for eight causes of death after adjusting for covariates in Model 2: cancer (1.07 [1.03, 1.11]); CHD (1.23 [1.17, 1.29]); COPD (1.28 [1.14, 1.43]); diabetes (1.56 [1.33, 1.83]); influenza/pneumonia (1.24 [1.02, 1.50]); Parkinson disease 1.35 [1.11, 1.65]); liver disease (1.33 [1.05, 1.67]); and suicide (1.43 [1.10, 1.85]) (Figure 1). Results for five causes of death were non-significant: sepsis (1.22 [0.97, 1.52]); kidney disease (1.18 [0.95, 1.47]); hypertension (1.21 [0.92, 1.59]); Alzheimer disease (1.12 [0.95, 1.31]); accidents (0.96 [0.83, 1.12]); and stroke (1.03 [0.93, 1.15]). There was no cause of death where TV viewing was protective. In the model without potential causal intermediaries (health status and BMI, Model 1), mortality risk was significantly increased for three additional causes of death (kidney, hypertension, and sepsis, Table 2), and the associations tended to be stronger. Influenza/pneumonia was the only cause of death where the mortality risk from TV viewing differed by sex (pint= 0.03), with stronger associations in women (Appendix Figure 1). In the categorical analyses, elevation in risk was initially observed for most outcomes at 3–4 hours/day of TV viewing (Table 2), compared with those watching <1 hour/day. When the 1–2 hours/day category was set as referent, the results were similar, though the precision of the estimates was improved (Appendix Table 2). Age- and sex-adjusted models are shown in Appendix Table 3.

Figure 1.

Association for a 2 h/day increase in TV viewing and the leading causes of death in the U.S.: NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study.

Note: Values are HRs and 95% CI, fully adjusted for covariates in Model 2.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

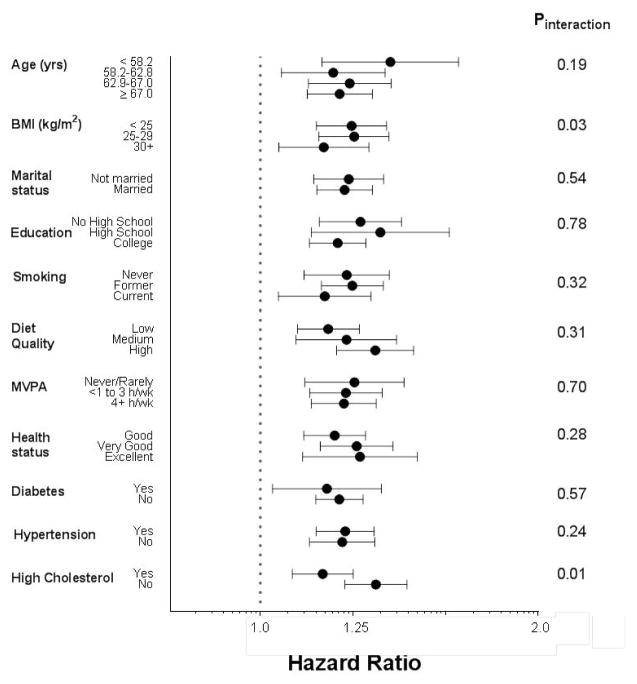

To investigate potential confounding and reverse causation, stratified analyses were conducted for the combined mortality outcome for other causes of death (i.e., excluding CVD and cancer), which included 6,824 (18.5%) deaths. The positive association between TV viewing and the combined causes of death were consistent across relevant subgroups (Figure 2). There was no interaction between TV viewing and age, MVPA, education, diet quality, marital, health, smoking, hypertension, or diabetes status. Risk estimates for TV viewing were higher in leaner individuals (p=0.03) and those without high cholesterol (p=0.01). Excluding the first 3 years of follow-up and limiting the sample to never smokers resulted in similar risk estimates (Appendix Table 4).

Figure 2.

Associations for a 2 h/day increase in TV viewing for other causes of death by baseline characteristics: NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study.

Note: Values are HRs and 95% CIs. Other causes of death included deaths due to COPD, diabetes, sepsis, hypertension, pneumonia and influenza, liver disease, kidney disease, suicide, accidents, Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease. Models were fully adjusted for covariates in Model 2, unless they were the comparator of interest. Diet quality is based on HEI-2005, “low” included bottom two quintiles and “high” included top two quintiles.

Joint Effects With Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity

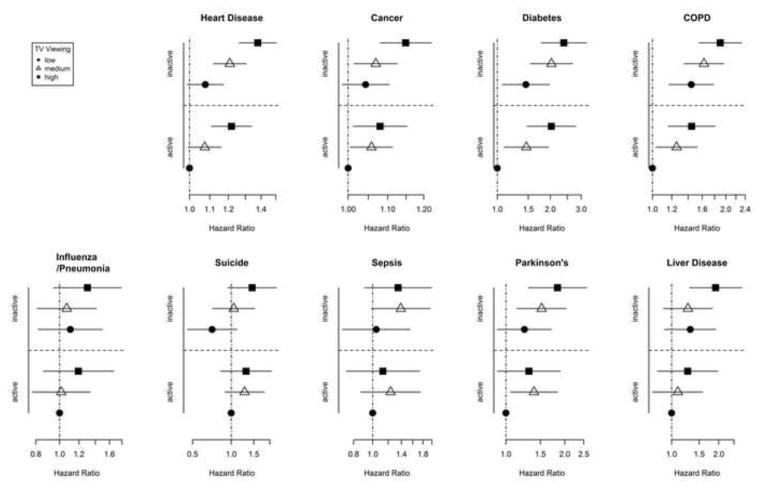

There was no significant interaction between MVPA and TV viewing (all p>0.05), indicating the detrimental effects of TV viewing were similar in active and inactive individuals. The joint effects of TV viewing and MVPA are shown Figure 3 for nine causes of death where a significant main effect of TV viewing was found. For the four leading causes (cancer, CHD, diabetes, and COPD), the estimates in the active/high TV group were equivalent to the inactive/low TV group. For example, for CHD the active/high TV HR was 1.21 (1.11, 1.34) and inactive/low TV HR was 1.08 (0.99, 1.17) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Joint effects of MVPA and TV viewing on selected Mortality outcomes NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study.

Note: Values are HRs and 95% CI. MVPA was categorized as active (≥4h/wk) or inactive is (<4h/wk). TV viewing was categorized as low (<2h/day), medium (3–4h/day), or high (≥5h/day). High active and low TV was set as referent group. Models were fully adjusted for covariates in Model 2.

Discussion

In this large prospective study of adults aged 50–71 years who were free of major chronic illness and reported good health, prolonged TV viewing was significantly associated with greater risk for eight of 14 leading causes of death in the U.S., including CHD, cancer, COPD, diabetes, influenza/pneumonia, Parkinson disease, liver disease, and suicide. There was evidence for a dose–response relationship for the majority of outcomes and the associations remained significant after adjustment for relevant confounders, including BMI, health status, and MVPA. Although the relations between TV viewing and CHD and cancer have been examined previously,4–7 the finding of elevated risk for other leading causes of death are novel and demonstrate for the first time the breadth of mortality outcomes that may be linked to prolonged TV viewing. Results from this study suggest that interventions targeting reductions in TV viewing, a single health behavior, have the potential to efficiently leverage a variety of health benefits and yield clinical and public health impact that is more expansive than previously known.

There are several plausible explanations for these results, and our central hypothesis is that physical inactivity resulting from prolonged TV viewing is a primary mechanism. On average, TV viewing consumes 55% of leisure time2 and has been associated with lower levels of leisure-time and total physical activity21,22 and lower cardiorespiratory fitness,23,24 an important determinant of which is inactivity. Conversely, a randomized trial that reduced TV viewing by 50% among adults who watched for at least 3 hours/day resulted in an increase of physical activity of 100 kcal/day,17 which is roughly equivalent to a mile of walking. A growing body of research indicates that displacement of physical activity with sedentary behavior, including TV viewing, can have adverse effects on energy balance and metabolic health. Experimental studies have shown that prolonged sitting increases postprandial glucose and insulin levels.25 Observational studies indicate that prolonged TV viewing is associated with weight gain,26 poor metabolic health,3,27 and increased risk for developing diabetes.11 This is the first study to report the association between TV viewing and diabetes mortality. Mortality from liver disease,28 infection,29 and COPD30–32 have also been linked to obesity and poor metabolic health, providing a plausible biological mechanism for these associations.

By contrast, for some of the novel mortality outcomes the explanations are less clear and this study presents intriguing hypothesis-generating results that should stimulate future research. For example, TV viewing has been associated with a prothombotic/inflammatory state (i.e., interleukin 6, C-reactive protein, and endothelial function)12,33,34 which, in turn, has been linked with progression of COPD,35 Parkinson disease,36 and sepsis mortality,29 perhaps due to inactivity associated with prolonged TV viewing. Similarly, TV viewing has been associated with lower cardiorespiratory fitness24 and muscle strength.37 Thus, prolonged TV time may adversely affect functional health and reduce one’s ability to withstand acute health events later in life (e.g., influenza/pneumonia, sepsis). More research is needed to fully understand the relations between TV viewing, inflammation, functional health, and mortality from these outcomes. The finding of a link between TV viewing and suicide was also novel and should be interpreted cautiously. Although there is an established relationship between physical activity and reduced risk of depression,38 and prolonged TV viewing has been prospectively associated with increased risk of depression,12–14,39 depression may also lead to prolonged TV viewing. Future studies are needed to clarify the temporal relation between prolonged TV viewing, depression, and suicide and to elucidate whether depression resides in the causal pathway for the observed TV–suicide mortality association, or simply acts as a confounder.

Prolonged TV viewing has also been associated with increased mortality from all-causes and cardiovascular disease3–6,40 but less is known about the relation with the individual components of CVD mortality, such as stroke. Seguin et al.7 reported a stronger association between TV viewing and mortality from CHD than for overall CVD in women, consistent with the present finding of a null association for TV viewing and stroke mortality. Previous studies of TV viewing and cancer mortality have been mixed.4,6,7,41,42 The present results, derived from double the number of deaths of the largest previous study, suggest a modest increase in cancer mortality with prolonged TV viewing, even among never smokers. In this study, the adverse effect of TV viewing was evident in both active and inactive individuals. This is consistent with several studies showing that prolonged sedentary behavior displaces primarily light and intermittent MVPA43 and associations between TV and health mortality remain after adjustment for structured MVPA.4,5,44 These results suggest both active and inactive individuals would benefit from interventions that reduce prolonged TV viewing.

Limitations

This study has limitations that should be noted. The cohort was primarily composed of white, educated older adults who were free of major chronic disease at baseline; hence, the generalizability of these results may be limited to similar populations. TV viewing was self-reported and assessed at a single time point, which may not adequately account for within-person variation in TV viewing and introduces measurement error that probably underestimates (attenuates) the strength of the observed associations. Our results for a 2-hour/day increase in risk are only valid throughout the range of the highest response option (9 or more hours/day) on our TV viewing questions. Some of the causes of death associated with TV viewing are also chronic conditions and information derived from death certificates may not always reflect the actual underlying cause of death. In particular, hypertension and diabetes mortality are typically associated with a cardiovascular event.45,46 There is the potential for residual confounding and may be error associated with self-reported covariates. Increased dietary intake may confound or mediate associations with TV viewing owing to increased snacking behavior,47,48 and though adjustment for and stratification by BMI and diet quality had minimal effect on risk estimates, it is possible that residual confounding persists. Depression has been associated with increased risk of suicide and early mortality49 and this analysis was unable to control for mental health status. Similarly, the primary indicator of SES (educational attainment) may not have completely adjusted for all of the socioeconomic determinants of mortality. Strengths of this study include a large sample size and long follow-up, which allowed the investigation of many causes of death that are difficult to evaluate in smaller studies. The large sample also allowed us to exclude individuals with major chronic diseases and poor/fair health at baseline to minimize concerns about reverse causality. Furthermore, stratified analyses revealed that risk associated with prolonged TV viewing persisted among individuals with and without comorbid conditions, excellent self-reported health, and in smokers and non-smokers, suggesting these results are robust.

Conclusions

Older adults watch the most TV of any demographic group in the U.S.2 In this large cohort of older adults, prolonged TV viewing was associated with higher risk for eight of 14 leading causes of death in the U.S. Given the increasing age of the population, the high prevalence TV viewing in leisure time, and the broad range of mortality outcomes for which risk appears to be increased, prolonged TV viewing may be a more important target for public health intervention than previously recognized.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the participants in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study for their outstanding cooperation. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute. The funder did not play any role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Neilson Reports. Households with Televisions. 2013 http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2013/nielsen-estimates-115-6-million-tv-homes-in-the-u-s---up-1-2-.html.

- 2.Bureau of Labor and Statistics. American Time Use Survey. 2012 www.bls.gov/tus/tables/a1_2013.pdf.

- 3.Grontved A, Hu FB. Television viewing and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305(23):2448–2455. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.812. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wijndaele K, Brage S, Besson H, et al. Television viewing time independently predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: the EPIC Norfolk study. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(1):150–159. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq105. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthews CE, George SM, Moore SC, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors and cause-specific mortality in U.S. adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(2):437–445. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.019620. http://dx.doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.019620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunstan DW, Barr EL, Healy GN, et al. Television viewing time and mortality: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study (AusDiab) Circulation. 2010;121(3):384–391. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894824. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seguin R, Buchner DM, Liu J, et al. Sedentary Behavior and Mortality in Older Women: The Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(2):122–135. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warren TY, Barry V, Hooker SP, Sui X, Church TS, Blair SN. Sedentary behaviors increase risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(5):879–885. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c3aa7e. http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c3aa7e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wijndaele K, Brage S, Besson H, et al. Television viewing and incident cardiovascular disease: prospective associations and mediation analysis in the EPIC Norfolk Study. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020058. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunstan DW, Salmon J, Healy GN, et al. Association of television viewing with fasting and 2-h postchallenge plasma glucose levels in adults without diagnosed diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(3):516–522. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1996. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc06-1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith L, Hamer M. Television viewing time and risk of incident diabetes mellitus: the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Diabet Med. 2014;31(12):1572–1576. doi: 10.1111/dme.12544. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/dme.12544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamer M, Poole L, Messerli-Burgy N. Television viewing, C-reactive protein, and depressive symptoms in older adults. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;33:29–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.05.001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lucas M, Mekary R, Pan A, et al. Relation between clinical depression risk and physical activity and time spent watching television in older women: a 10-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174(9):1017–1027. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwr218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mekary RA, Lucas M, Pan A, et al. Isotemporal substitution analysis for physical activity, television watching, and risk of depression. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(3):474–483. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws590. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schatzkin A, Subar AF, Thompson FE, et al. Design and serendipity in establishing a large cohort with wide dietary intake distributions: the National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(12):1119–1125. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1119. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/154.12.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall AL, Miller YD, Burton NW, Brown WJ. Measuring total and domain-specific sitting: a study of reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(6):1094–1102. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c5ec18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c5ec18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otten JJ, Jones KE, Littenberg B, Harvey-Berino J. Effects of television viewing reduction on energy intake and expenditure in overweight and obese adults: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2109–2115. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.430. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. National vital statistics reports. 4. Vol. 61. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. Deaths: Final data for 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, et al. Performance of a food-frequency questionnaire in the U.S. NIH-AARP (National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons) Diet and Health Study. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(2):183–195. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007000419. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1368980007000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guenther PM, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Development of the Healthy Eating Index-2005. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(11):1896–1901. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.08.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugiyama T, Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, Owen N. Is television viewing time a marker of a broader pattern of sedentary behavior? Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(2):245–250. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9017-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12160-008-9017-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tucker LA, Tucker JM. Television viewing and obesity in 300 women: evaluation of the pathways of energy intake and physical activity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(10):1950–1956. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.184. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/oby.2011.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tucker LA. Television viewing and physical fitness in adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1990;61(4):315–320. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1990.10607493. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1990.10607493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tucker LA, Arens PJ, Lecheminant JD, Bailey BW. Television Viewing Time and Measured Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Adult Women. Am J Health Promot. 2014 doi: 10.4278/ajhp.131107-QUAN-565. Epub ahead of print. http://dx.doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.131107-QUAN-565. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Dunstan DW, Kingwell BA, Larsen R, et al. Breaking up prolonged sitting reduces postprandial glucose and insulin responses. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(5):976–983. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1931. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc11-1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitchell JA, Bottai M, Park Y, Marshall SJ, Moore SC, Matthews CE. A Prospective Study of Sedentary Behavior and Changes in the BMI Distribution. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(12):2244–2452. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thorp AA, Owen N, Neuhaus M, Dunstan DW. Sedentary behaviors and subsequent health outcomes in adults a systematic review of longitudinal studies, 1996–2011. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(2):207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith BW, Adams LA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes mellitus: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(8):456–465. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2011.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertoni AG, Saydah S, Brancati FL. Diabetes and the risk of infection-related mortality in the U.S. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(6):1044–1049. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1044. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diacare.24.6.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agusti A, Calverley PM, Celli B, et al. Characterisation of COPD heterogeneity in the ECLIPSE cohort. Respir Res. 2010;11:122. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decramer M, Janssens W, Miravitlles M. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1341–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60968-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60968-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Seshasai SR, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(9):829–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008862. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1008862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allison MA, Jensky NE, Marshall SJ, Bertoni AG, Cushman M. Sedentary behavior and adiposity-associated inflammation: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.09.023. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Henson J, Yates T, Edwardson CL, et al. Sedentary time and markers of chronic low-grade inflammation in a high risk population. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e78350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fabbri LM, Luppi F, Beghe B, Rabe KF. Complex chronic comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(1):204–212. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114307. http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00114307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pessoa Rocha N, Reis HJ, Vanden Berghe P, Cirillo C. Depression and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: a role for inflammation and immunomodulation? Neuroimmunomodulation. 2014;21(2–3):88–94. doi: 10.1159/000356531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Screen-based sedentary behavior, physical activity, and muscle strength in the English longitudinal study of ageing. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e66222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, O’Neal HA. Physical activity dose-response effects on outcomes of depression and anxiety. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(6 Suppl):S587–S597. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00027. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200106001-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamer M, Stamatakis E, Mishra GD. Television- and screen-based activity and mental well-being in adults. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4):375–380. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ford ES. Combined television viewing and computer use and mortality from all-causes and diseases of the circulatory system among adults in the United States. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.George SM, Smith AW, Alfano CM, et al. The association between television watching time and all-cause mortality after breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(2):247–252. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0265-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0265-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, et al. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):219–229. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW, Winkler EA, Owen N. Sedentary time and cardio-metabolic biomarkers in U.S. adults: NHANES 2003–06. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(5):590–597. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq451. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehq451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matthews CE, Moore SC, Sampson J, et al. Mortality Benefits for Replacing Sitting Time with Different Physical Activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000621. Epub ahead of print. http://dx.doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Cheng TJ, Lin CY, Lu TH, Kawachi I. Reporting of incorrect cause-of-death causal sequence on death certificates in the USA: using hypertension and diabetes as an educational illustration. Postgrad Med J. 2012;88(1046):690–693. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-130912. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-130912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheng TJ, Lu TH, Kawachi I. State differences in the reporting of diabetes-related incorrect cause-of-death causal sequences on death certificates. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(7):1572–1574. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2156. http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc11-2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harris JL, Bargh JA, Brownell KD. Priming effects of television food advertising on eating behavior. Health Psychol. 2009;28(4):404–413. doi: 10.1037/a0014399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thorp AA, McNaughton SA, Owen N, Dunstan DW. Independent and joint associations of TV viewing time and snack food consumption with the metabolic syndrome and its components; a cross-sectional study in Australian adults. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10(1):96. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-96. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cuijpers P, Vogelzangs N, Twisk J, Kleiboer A, Li J, Penninx BW. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis of Excess Mortality in Depression in the General Community Versus Patients With Specific Illnesses. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(4):453–462. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13030325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.