Abstract

Galactocerebroside (GalC) and its sulfated derivative sulfatide (SUL) are galactosphingolipids abundantly expressed in oligodendrocytes (OLs). Despite their biological importance in OL development and function, attempts to visualize GalC/SUL in tissue sections have met with limited success. This is at least in part because permeabilization of tissue sections with detergents such as Triton X-100 results in significant degradation of GalC/SUL immunoreactivity. Here we establish a novel method that enables visualization of endogenous GalC/SUL in OLs and myelin throughout the entire depth of brain sections. We show that treating brain sections with the cholesterol-specific detergent digitonin instead of Triton X-100 or methanol leads to efficient antibody penetration into tissue sections without disrupting GalC/SUL immunoreactivity. We also determine the optimal concentrations of digitonin using confocal microscopy. With our method, the morphology and the number of GalC/SUL-expressing OLs can be visualized three-dimensionally. Furthermore, our method is applicable to double immunostaining with anti-GalC/SUL antibody and other antibodies which recognize intracellular antigens. Our simple method using digitonin should prove to be useful in enabling detailed examination of GalC/SUL expression in the brain in both physiological and pathological conditions.

Keywords: Galactocerebroside, Galactosphingolipid, Digitonin, Cholesterol-specific detergent, Oligodendrocyte, Immunohistochemistry

1. Introduction

Oligodendrocytes (OLs) are responsible for myelination in the central nervous system. The differentiation of OL lineage cells, including OL progenitor cells (OPCs), premyelinating and myelinating OLs, is characterized by sequentially expressed OL lineage-specific glycolipids and proteins (Raff, 1989; Pfeiffer et al., 1993; Stoffel and Bosio, 1997; Marcus and Popko, 2002; Miller, 2002). Immunohistochemical detection of these antigens allows the identification of defined phenotypes of the OL lineage during development. Among the most abundant OL-specific lipids are galactocerebroside (GalC) and its sulfated derivative sulfatide (SUL), which together constitute ~27% of the myelin lipid (Norton and Autilio, 1966). Their abundance and cellular specificity have made GalC/SUL particularly useful as one of the earliest markers of postmitotic OLs (Raff et al., 1978). Moreover, because GalC/SUL immunoreactivity is distributed almost entirely throughout OL membranes (Mirsky et al., 1980; Knapp et al., 1988), GalC/SUL can be used to visualize morphological changes of OLs during development. In addition, in mice lacking UDP-galactose ceramide galactosyltransferase (CGT), the key enzyme of GalC/SUL biosynthesis, OL processes are not properly positioned along the axon, resulting in conduction deficits and abnormal formation of nodes of Ranvier (Bosio et al., 1996; Coetzee et al., 1996; Dupree et al., 1998). Because of the importance of Gal/SUL, the analyses of GalC/SUL expression in vivo are crucial for understanding OL differentiation and myelin function.

Although the expression of GalC/SUL in cultured OLs has been extensively investigated (Raff et al., 1978; Mirsky et al., 1980; Ranscht et al., 1982), in vivo this has been relatively difficult to examine. This is, at least partially, because immunohistochemical localization of GalC/SUL in tissue sections is not very easy to perform (Monge et al., 1986; Ghandour and Skoff, 1988; Reynolds and Wilkin, 1988). GalC/SUL immunoreactivity is severely degraded by Triton X-100, a detergent commonly used to enhance antibody penetration into tissue sections, as in the cases of other lipid molecules and lipophilic tracers (Reynolds and Wilkin, 1988; Schwarz and Futerman, 2000; Matsubayashi et al., 2008). Presumably, this is because GalC/SUL are eluted from the OL membrane by Triton X-100. One possible solution to this problem is to omit permeabilization steps with Triton X-100 during immunostaining protocols. Indeed, the distribution patterns of GalC in fixed brain sections have been examined without permeabilization (Curtis et al., 1988; Ghandour and Skoff, 1988; Reynolds and Wilkin, 1988; Hardy and Reynolds, 1991). However, without permeabilization, only the antigens located at the surface of sections are labeled, and those buried in the middle of sections remain unstained (Matsubayashi et al., 2008). Accordingly, without using detergents, it is difficult to examine the three-dimensional distribution of GalC/SUL, the morphological differentiation and the number of OLs in sections comprehensively. Previously, Warrington and Pfeiffer employed unfixed tissue sections and visualized the distribution patterns of glycolipids (Warrington and Pfeiffer, 1992). However, because anti-glycolipid antibodies often have biological effects on cultured OLs such as disruption of cytoskeletons and calcium influx into OLs (Dyer and Benjamins, 1989, 1990), the incubation of unfixed tissues with anti-glycolipid antibodies could have unexpected effects on OLs during immunohistochemical procedures. It is therefore desirable to establish a new immunohistochemical method that enhances antibody penetration into tissue sections without disturbing GalC/SUL immunoreactivity.

We decided to fabricate a new immunohistochemical procedure to visualize GalC/SUL using fixed tissue sections. Recently, we developed an immunohistochemical method for tissue sections labeled with DiI, a lipophilic neuronal tracer that is also incompatible with staining protocols using Triton X-100 (Matsubayashi et al., 2008). Instead of Triton X-100, which solubilizes lipid molecules almost indiscriminately (Schuck et al., 2003), we permeabilized DiI-labeled sections with digitonin, a cholesterol-specific detergent (Gogelein and Huby, 1984). We found that treatment of DiI-labeled brain sections with digitonin led to efficient antibody penetration into the sections without disrupting DiI labels in neurons (Matsubayashi et al., 2008).

Similarly, we reasoned that digitonin would also preserve the distribution patterns of an endogenous glycolipid GalC/SUL. Consistent with this hypothesis, we here show that digitonin treatment leads to efficient antibody penetration into tissue sections without disrupting GalC/SUL immunoreactivity. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first application of digitonin for immunofluorescent staining of endogenous glycolipid antigens in brain sections, even though digitonin has often been used for cell biological and biochemical assays such as membrane permeabilization and protein extraction (Bittner and Holz, 1988; Adam et al., 1990; Matsubayashi et al., 2001; Geelen, 2005; Ohsaki et al., 2005; Krause, 2006). The ability to visualize GalC/SUL distribution in fixed brain sections should prove useful in enabling detailed examination of GalC/SUL expression in both physiological and pathological conditions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

ICR and C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Japan SLC (Hamamatsu, Japan). Olig1-deficient mice (Xin et al., 2005) were maintained on a 129 and C57BL/6 hybrid background, and genotypes of Olig1-deficient mice were determined as described (Toda et al., 2008).All mice were reared on a normal 12 h light/dark schedule. All procedures were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the animal experiment committee at the University of Tokyo.

2.2. Antibodies and reagents

Anti-GalC/SUL antibody (“R-mAb”) was a kind gift from Dr. Barbara Ranscht (The Burnham Institute, La Jolla, CA) (Ranscht et al., 1982). O4, anti-NeuN, Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse IgM antibodies were from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). Anti-myelin basic protein (MBP) antibody and CC1 antibody were from Covance (Berkeley, CA) and Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA), respectively. Alexa488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG3 and Alexa568-conjugated anti-mouse IgG1 antibodies were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse IgG2 antibody was from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). Digitonin was purchased from Calbiochem (catalog no. 300411) and stocked in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, purchased from Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a concentration of 50 mg/ml at −20°C. When used, the stock solution was diluted at least 100 folds.

2.3. Preparation of brain sections

Mice were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). The brains were dissected out and post-fixed overnight at 4°C with 4% PFA/PBS. Then the brains were sectioned with a vibratome (30 µm thickness) and stored in PBS containing 0.03% sodium azide.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously with modifications (Kawasaki et al., 2000; Matsubayashi et al., 2008). Brain sections were pretreated with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/PBS containing DMSO (0.24–1%), digitonin (60–500 µg/ml) or 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature (RT) and incubated with primary antibodies in each pretreatment solution for 12 h at 4°C. For methanol permeabilization, the sections were incubated in methanol for 30 min at −20 °C, washed with PBS, and then incubated with primary antibodies in 3% BSA/PBS for 12 h at4°C. After incubation with primary antibodies, the sections were washed with PBS, incubated with secondary antibodies and Hoechst 33342 (final 1 µg/ml, purchased from Calbiochem) in 3% BSA/PBS for 3 h at RT and washed with PBS. Then the sections were attached to microscope slides and coverslipped using Mowiol (Calbiochem). The antibody dilutions were as follows: anti-GalC/SUL, 1:100; CC1, 1:1000; anti-MBP, 1:1000; O4, 1:500; anti-NeuN, 1:1000; Cy3-conjugated anti-mouse IgG2, 1:1000; all other secondary antibodies, 1:500.

2.5. Microscopy

Microscopic analyses were performed as described previously (Matsubayashi et al., 2008). Epifluorescence microscopy was carried out with an Axioimager A1 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany). Confocal microscopy was performed using a LSM510 microscope with 40 × /1.3NA objective (Carl Zeiss). Z-stack images (2.1 µm optical thickness) were collected every 1.75 µm and three-dimensionally (3D) reconstructed using ZEN 2007 and ZEN 2007 LE software (Carl Zeiss). The images are shown either as single XY- or XZ-optical sections or as XZ-maximum projection images, in which 3D views of the data were calculated and displayed by only showing pixels with the highest intensity along the projection axis. For quantification of immunofluorescence intensities across the sections (Fig. 6B), rectangular regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn in the XZ-maximum projection images across the entire width (220 µm) and depth (~20–30 µm) of the brain sections. The horizontally averaged pixel intensities were measured and plotted against the depth using ImageJ (public domain software, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Fig. 6.

Digitonin enhances antibody penetration into brain tissues. Fixed cerebral cortices were dissected out from P8 mice. Coronal brain sections were made using a vibratome and stained with anti-GalC/SUL antibody using either 3% BSA/PBS, 1% DMSO or 60–500 µg/ml digitonin. GalC/SUL immunoreactivity in layer VI was examined using confocal microscopy. (A) The Z-stack confocal images were three-dimensionally reconstructed as maximum projection images (see Section 2 for details), and the representative side views of the reconstructed images are displayed. The width of each panel is 50 µm. (B) Relationships between fluorescence intensities and the depth in tissue sections. Fluorescence intensities in the XZ-maximum projection images are plotted against the depth in tissue sections as described in Section 2. The horizontal axis represents the depth in tissue sections, and the vertical axis represents fluorescence intensities at each depth. Note that valleys at the middle of BSA/PBS- and DMSO-treated tissues (dark and light blue circles, respectively) were markedly shallowed in digitonin-treated tissues (light green triangles, dark green triangles, orange squares and red squares), suggesting that antibody penetration into tissue sections is significantly enhanced by digitonin treatment. (C) Single XY-optical sections (i.e., optical sections parallel to the coverslip) at the surface and at the middle of the brain sections are displayed. Note that formation of GalC/SUL blebs was minimal in the middle of the brain sections, while the blebs appeared in a manner dependent on the concentration of digitonin at the surface (arrowheads). Scale bar = 50 µm.

2.6. Data analyses of the subcellular localization of NeuN immunoreactivity

Quantitative analyses of the subcellular localization of NeuN immunoreactivity were performed as described previously with modifications (Matsubayashi et al., 2001). The subcellular localization of NeuN immunoreactivity at the middle of each tissue section was visually inspected and classified into the following two categories: “N ≥ C”, nuclear NeuN immunoreactivity was stronger than or equal to cytoplasmic immunoreactivity; “N < C”, cytoplasmic immunoreactivity was stronger than nuclear immunoreactivity. The number of cells classified into each category was counted and used for further statistical analyses. To assess statistical significance, the absolute numbers of the cells classified in each category were listed in 2 × 2 contingency tables (e.g., DMSO-treated vs. digitonin-treated samples and “N ≥ C” vs. “N < C”), and were analyzed by Mantel–Haenszel procedure using Statcel2 software (OMS Publishing Inc., Saitama, Japan).

3. Results

3.1. The effects of digitonin and other permeabilizing reagents on GalC/SUL immunoreactivity in brain sections

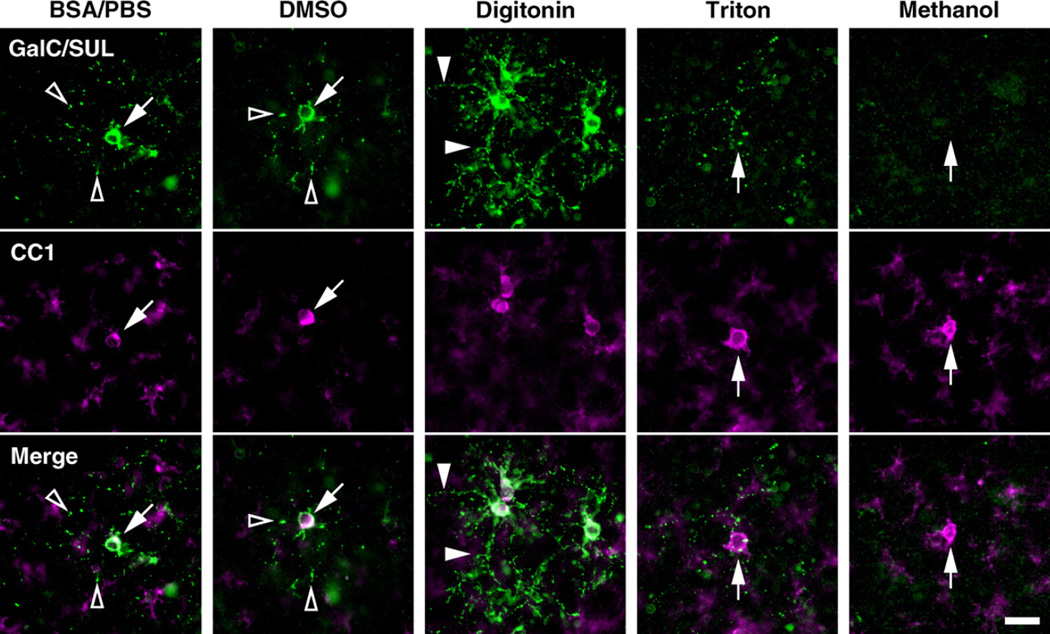

We first compared the effects of various permeabilizing reagents on GalC/SUL immunoreactivity in mouse brain sections. We used the monoclonal antibody R-mAb (Ranscht et al.,1982), which recognizes both GalC and SUL as well as other structurally related minor lipids (Bansal et al., 1989). Hereafter, this antibody is referred to as “anti-GalC/SUL antibody”. The fixed brains of P8 mice were dissected out, and coronal sections were made using a vibratome. The sections were then double-stained with anti-GalC/SUL and CC1 antibodies using either control BSA/PBS, DMSO, digitonin, Triton X-100 or methanol. CC1 antibody recognizes APC, a protein that is prominently expressed in OL cell bodies (Bhat et al., 1996). Because we found that CC1 immunoreactivity was not significantly disrupted by various permeabilizing reagents (Fig. 1), we used CC1 antibody to locate the position of OL cell bodies. When the sections were stained using BSA/PBS only, GalC/SUL and CC1 immunoreactivities were detected only at the surface of the sections (Fig. 1, BSA/PBS, see also Fig. 6). GalC/SUL+CC1 + OL cell bodies (Fig. 1, BSA/PBS, arrow) were often surrounded by GalC/SUL+ puncta (Fig. 1, BSA/PBS, open arrowheads). It is most likely that these puncta represent OL processes extending to the surface of the sections. Treatment of sections with DMSO, the solvent for digitonin, provided essentially similar results (Fig. 1, DMSO). In contrast, in the sections treated with 120 µg/ml digitonin, GalC/SUL+ processes were more clearly and continuously stained than those in the BSA/PBS- or DMSO-treated ones (Fig. 1, Digitonin, closed arrowheads). This result suggests that digitonin treatment enhances antibody penetration into sections, while at the same time preserving GalC/SUL distribution (see also Fig. 6). On the other hand, when sections were treated with Triton X-100, GalC/SUL immunoreactivity was severely disrupted, leaving a lot of bleb-like labels around CC1+ OL cell bodies (Fig. 1, Triton). In addition, GalC/SUL immunoreactivity almost completely disappeared after methanol treatment (Fig. 1, Methanol). These results are consistent with previous reports that Triton X-100 and organic solvents are not compatible with immunostaining for GalC/SUL and other lipid molecules (Reynolds and Wilkin, 1988; Schwarz and Futerman, 2000). Therefore, we decided to use digitonin in the following experiments.

Fig. 1.

The effects of digitonin and other permeabilizing reagents on GalC/SUL immunoreactivity in fixed brain sections. The fixed brains of P8 mice were dissected out, and coronal sections were taken from cerebral cortices using a vibratome. The sections were double-stained with anti-GalC/SUL antibody (green) and CC1 antibody (magenta) using either control 3% BSA/PBS, 0.24% DMSO, 120 µg/ml digitonin, 0.5% Triton X-100 or methanol. For details of the staining protocols, see Section 2. CC1 immunoreactivity indicates the position of OL cell bodies. Note that GalC/SUL immunoreactivity in OLs was obvious using digitonin, whereas the immunoreactivity almost totally disappeared after Triton X-100 or methanol treatment. Arrows, cell bodies of OLs; open arrowheads, GalC/SUL+ puncta around OL cell bodies; closed arrowheads, OL processes that are continuously labeled by anti-GalC/SUL antibody. Scale bar= 10 µm.

3.2. Characterization of GalC/SUL+ cells and structures in digitonin-treated sections

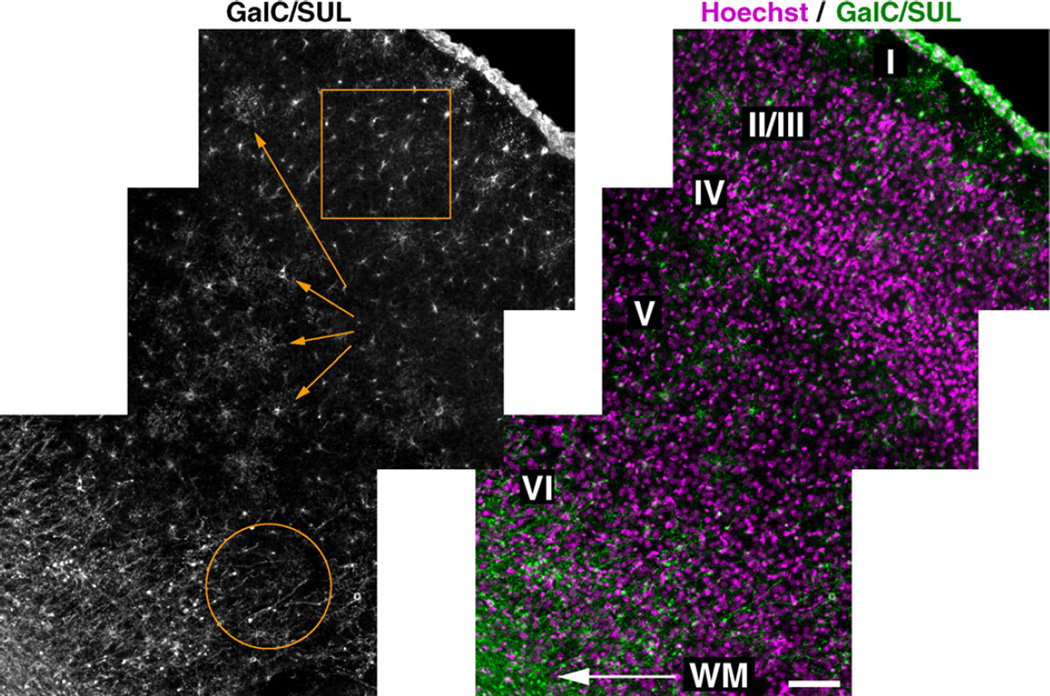

Because our immunostaining method using digitonin enabled us to examine co-localization of GalC/SUL and other OL markers at high spatial resolution, we then characterized GalC/SUL+ cells and structures in the cerebral cortex. In digitonin-treated sections, two morphologically distinct OLs were labeled by anti-GalC/SUL antibody. The first OLs had elaborate, rosette-like processes radially extending from the soma (Fig. 2, arrows). Double immunostaining showed that most of these OLs were positive for both CC1 (Fig. 3B, arrows) and O4 (data not shown) (Hereafter we refer to these cells as O4+CC1+ OLs). The second OLs had a few short simple processes occasionally (Fig. 2, square). Double immunostaining showed that these cells were CC1-negative (Fig. 3B, arrowheads) and O4-positive (Fig. 3C, arrowheads) (Hereafter we refer to these cells as O4+CC1− OLs). Because of their simpler morphology, it is conceivable that O4+CC1− OLs are at an earlier stage of the development than O4+CC1+ OLs. In addition to these cells, relatively linear fibers, most of which were located around the white matter, were labeled with anti-GalC/SUL antibody (Fig. 2, circle). Double immunostaining showed that the GalC/SUL+ fibers were also positive for MBP (Fig. 3A, open arrowheads, see also Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting that these fibers are myelin sheaths.

Fig. 2.

Panoramic view of the cerebral cortex stained with anti-GalC/SUL antibody using digitonin. Coronal vibratome sections of fixed P8 mouse brain were double-stained with anti-GalC/SUL antibody and Hoechst 33342 using 60 µg/ml digitonin. (Left) GalC/SUL immunostaining. The circle, arrows and square indicate myelin, O4+CC1+ OLs and O4+CC1− OLs, respectively. See also Fig. 3 and text for details. (Right) The GalC/SUL immunostaining shown in the left panel is merged with Hoechst staining. The positions of cortical layers and white matter (WM) are also shown. Scale bar= 100 µm.

Fig. 3.

Co-localization of GalC/SUL and other OL markers revealed by double immunostaining using digitonin. The fixed brains of P8 mice were dissected out, and coronal sections were taken from cerebral cortices using a vibratome. The sections were stained with anti-GalC/SUL antibody plus either anti-MBP (A), CC1 (B) or O4 (C) antibody using 60–120 µg/ml of digitonin. Note the colocalization of GalC/SUL and MBP in myelin (A, open arrowheads). GalC/SUL+ OLs with elaborate processes were also labeled with CC1 antibody (B, arrows). GalC/SUL+ OLs with a few simple processes were O4-positive and CC1-negative (B and C, closed arrowheads). Scale bars = 50 µm.

To exclude the possibility that digitonin treatment might alter the properties of molecules other than GalC/SUL and that they might happen to be recognized by anti-GalC/SUL antibody, we examined if GalC/SUL immunoreactivity disappears in the absence of OLs using Olig1-deficient mice. Olig1 is a basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor that is essential for OL differentiation (Lu et al., 2002; Zhou and Anderson, 2002), and OLs are markedly reduced in Olig1-deficient mice (Xin et al., 2005). When brain sections from Olig1-deficient mice were stained with anti-GalC/SUL antibody using digitonin, GalC/SUL immunoreactivity was markedly reduced(Fig.4). Collectively, the results in Figs. 2–4 strongly suggest that GalC/SUL can be reliably detected with anti-GalC/SUL antibody using digitonin treatment.

Fig. 4.

GalC/SUL expression in Olig1-deficient mice was examined using digitonin. Fixed brains of P8 wild-type (+/+) or Olig1-deficient (−/−) mice were dissected out, and coronal vibratome sections were taken from cerebral cortices. The sections were stained with anti-GalC/SUL antibody and Hoechst 33342 using 120 µg/ml digitonin. (Left panels) Low magnification images of Hoechst staining. (Middle and right panels) High magnification images of GalC/SUL immunostaining in the boxed areas 1–4 in the left panels. Note that GalC/SUL immunoreactivity was markedly reduced in Olig1-deficient mice. Scale bars = 500 µm (left); 50 µm (right).

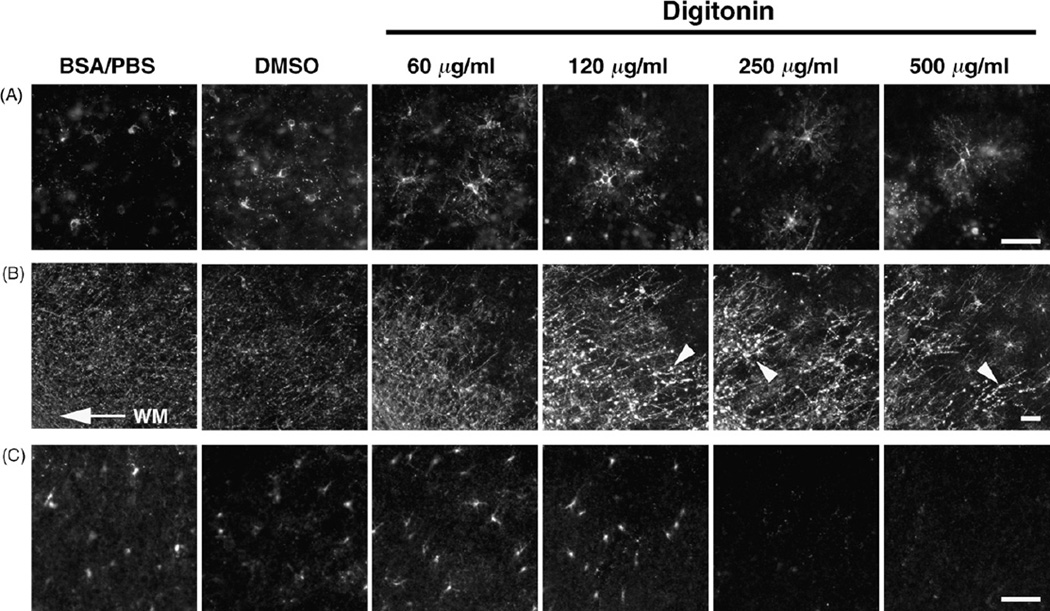

3.3. Concentration-dependent effect of digitonin on GalC/SUL immunoreactivity

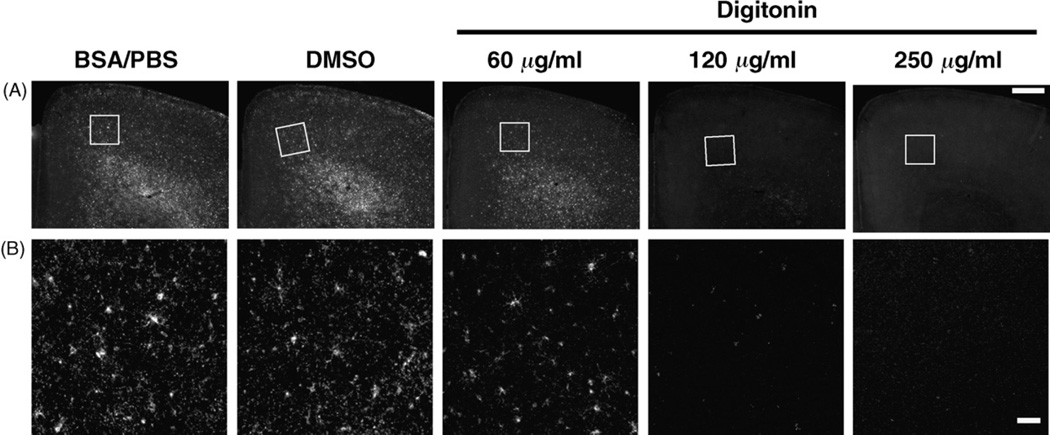

To determine the concentration of digitonin optimal for both enhancing antibody penetration into sections and preserving GalC/SUL distribution, we examined the effects of various concentrations (60–500 µg/ml) of digitonin on GalC/SUL immunoreactivity. P8 mouse brain sections were stained with anti-GalC/SUL antibody using various concentrations of digitonin. In the sections treated with 60 µg/ml digitonin, OL processes (Fig. 5A) and myelin (Fig. 5B) were more clearly and more continuously labeled than those in control BSA/PBS- or DMSO-treated sections. OLs and myelin were also clearly detected in the sections treated with higher concentrations (120–500 µg/ml) of digitonin (Fig. 5A and B). However, bleb-like structures of GalC/SUL labels appeared in a manner dependent on the concentration of digitonin, presumably due to partial degradation of GalC/SUL immunoreactivity (Fig. 5B, arrowheads, see also Fig. 6C). On the other hand, GalC/SUL immunoreactivity in O4+CC1− OLs disappeared in a manner dependent on the concentration of digitonin, and was undetectable if the sections were treated with digitonin at a concentration of 250 µg/ml or above (Fig. 5C, lower magnification images are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1). These results suggest that the optimal concentration of digitonin is about 60–120 µg/ml.

Fig. 5.

The concentration-dependent effect of digitonin on GalC/SUL immunoreactivity. Fixed brains of P8 mice were dissected out, and coronal sections of cerebral cortices were made using a vibratome. The sections were stained with anti-GalC/SUL antibody using either 3% BSA/PBS, 1% DMSO or 60–500 µg/ml digitonin. The representative images of O4+CC1+ OLs (A), myelin (B) and O4+CC1− OLs (C) are shown. Arrow, the position of the white matter (WM); arrowheads, bleb-like structures of GalC/SUL labels caused by digitonin treatment. Scale bars = 50 µm.

Next, we examined the depth of anti-GalC/SUL antibody penetration into digitonin-treated sections of the cerebral cortex. P8 mouse brain sections were stained with anti-GalC/SUL antibody using either 3% BSA/PBS, 1% DMSO or 60–500 µg/ml digitonin, and then GalC/SUL immunoreactivity in layer VI was examined by using confocal microscopy. In control BSA/PBS- and DMSO-treated sections, the immunoreactivity at the middle of the sections was faint (Fig. 6A and C, BSA/PBS and DMSO, see also Supplementary Fig. 2A). Consistently, when immunofluorescence intensities were measured and plotted against the depth in the sections, intensity profiles showed deep valleys at the middle of the sections (Fig. 6B, BSA/PBS and DMSO). In contrast, in digitonin-treated samples, the immunoreactivity at the middle of the sections was markedly enhanced in a manner dependent on the concentration of digitonin (Fig. 6A and C, digitonin, see also Supplementary Fig. 2B). Accordingly, the valleys of the intensity-depth plots were markedly shallower in digitonin-treated sections (Fig. 6B, Digitonin). These results demonstrate that digitonin treatment significantly enhances antibody penetration into tissue sections of the cerebral cortex. Taken together with our previous report that digitonin also enhanced antibody penetration into cerebellar sections (Matsubayashi et al, 2008), these results suggest that digitonin treatment can be applied to various brain regions.

As shown in Fig. 5B (arrowheads), bleb-like structures of GalC/SUL labels appeared in a manner dependent on the concentrations of digitonin, suggesting that digitonin treatment may cause some degradation of GalC/SUL immunoreactivity. Importantly, however, only a few blebs appeared when sections were treated with 60 µg/ml digitonin. Furthermore, even when sections were treated with higher concentrations of digitonin, confocal microscopy demonstrated that these blebs were restricted to the surface of the sections, and digitonin treatment significantly improved GalC/SUL immunoreactivity at the middle of the sections (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these results demonstrate that digitonin treatment significantly enhances GalC/SUL immunoreactivity with minimal degradation, especially when sections were treated with 60–120 µg/ml digitonin. Indeed, by using 120 g/ml digitonin, but not DMSO, OL processes were successfully visualized throughout the entire depth of the sections (Supplementary Movies 1 and 2).

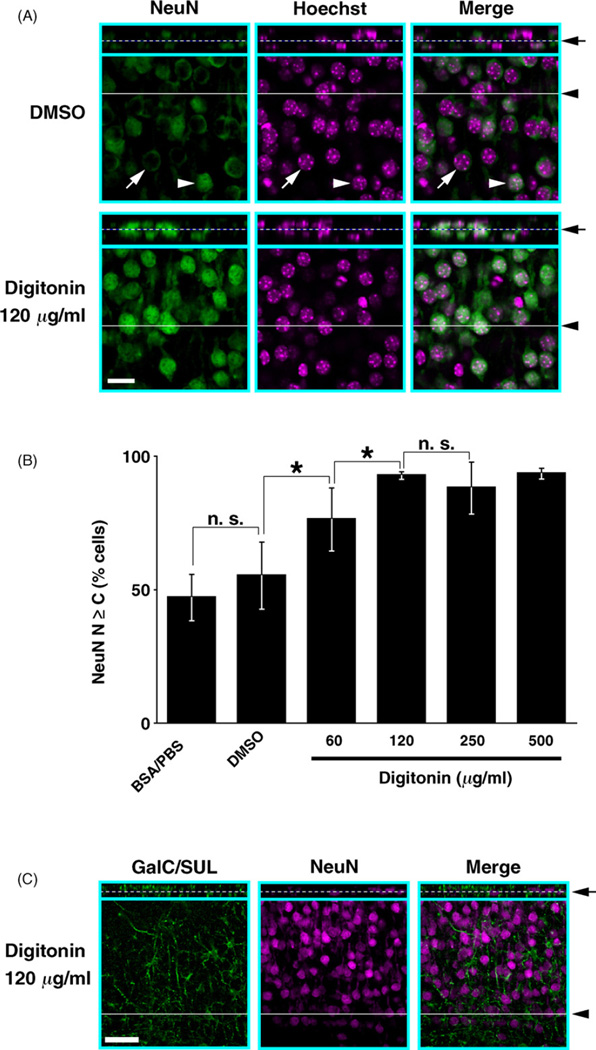

3.4. Nuclear envelopes are also permeabilized with digitonin treatment

One of the cellular membranes supposed to be the most resistant to digitonin is the nuclear envelope, because it contains the least amount of cholesterol, the target of digitonin (Elias et al., 1978; Adam et al., 1990; van Meer et al., 2008). Therefore, it seemed that one possible limitation of our method was that it might not be applicable to immunostaining of nuclear antigens. If so, double staining with anti-GalC/SUL antibody and other antibodies against nuclear antigens would not be possible. However, we previously demonstrated that even nuclear antigens can be successfully detected by using digitonin at a concentration of 1000 µg/ml (Matsubayashi et al., 2008). Here, we examined whether lower concentrations of digitonin are sufficient to permeabilize nuclear envelopes and detect nuclear antigens because 500 µg/ml digitonin degraded GalC/SUL immunoreactivity. Using various concentrations of digitonin, we stained cortical sections with an antibody against NeuN, which is expressed in most neurons of mouse brains and is localized mainly in the cell nucleus as well as in the cytoplasm (Mullen et al., 1992; Lind et al., 2005). NeuN immunoreactivity at the middle of the sections was analyzed using confocal microscopy.

In control DMSO-treated sections, NeuN immunoreactivity was weak at the middle of the sections (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, this weak NeuN immunoreactivity was often predominantly located in the cytoplasm with little immunoreactivity in the nucleus (Fig. 7A, DMSO, white arrows). The percentage of neurons in which NeuN immunoreactivity in the nucleus was equal to or higher than that in the cytoplasm (Fig. 7A, DMSO, white arrowheads. Hereafter, this percentage is referred to as “N ≥ “ value) was about 55% (Fig. 7B, DMSO). It is most likely that in these cells, nuclear NeuN was labeled by the antibody due to incidental physical breakage of the nuclear envelope that occurred during vibratome sectioning. Essentially similar results were obtained with BSA/PBS-treated sections (Fig. 7B, BSA/PBS).

Fig. 7.

Nuclear antigens are detectable using digitonin permeabilization. Fixed brains of P8 mice were dissected out, and coronal sections of cerebral cortices were made using a vibratome. The sections were stained with anti-NeuN and anti-GalC/SUL antibodies using either 3% BSA/PBS, 1% DMSO or 60–500 µg/ml digitonin. The sections were also counterstained with Hoechst 33342. Then the sections were examined using confocal microscopy, and the Z-stack images were three-dimensionally reconstructed. (A) Representative images of the brain sections stained with anti-NeuN antibody using DMSO or 120 µg/ml digitonin. XY-optical sections at the middle of the tissues are shown in squares. Images corresponding to vertical XZ-optical sections reconstructed along white solid lines (black arrowheads) are displayed at the top of eachXY-optical section. White dashed lines (black arrows) indicate the vertical position of the displayed XY-optical sections. White arrows, a neuron with minimal nuclear NeuN immunoreactivity; white arrowheads, a neuron with strong nuclear NeuN immunoreactivity. (B) Quantification of neurons with NeuN+ nuclei. Shown are the percentages of cortical neurons in which nuclear NeuN immunoreactivity was stronger than or equal to cytoplasmic immunoreactivity (means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments, n = 78–131). Asterisks, p < 0.001; n.s., not significant (p>0.05). (C) Representative images of the brain section double-stained with anti-GalC/SUL and anti-NeuN antibodies using 120 µg/ml digitonin. XY-optical sections at the middle of the brain section and XZ-optical sections reconstructed along white solid line (black arrowhead) are displayed as in (A). White dashed line (black arrow) indicates the vertical position of the displayed XY-optical sections. Scale bars = 20 µm (A); 50 µm (C).

In contrast, in digitonin-treated sections, “N ≥ C” value was significantly increased depending on digitonin concentrations, and reached a plateau value of ~93% when digitonin concentration was increased up to 120 g/ml or greater (Fig. 7B). Thus, in the middle of brain sections treated with 120 µg/ml digitonin, nuclear NeuN immunoreactivity was successfully detected in almost all NeuN+ cells (Fig. 7A, Digitonin 120 µg/ml). Taken together, these results demonstrate that even antigens in the cell nucleus can be successfully detected with our method by using digitonin at a concentration of 120 µg/ml. Indeed, using this concentration of digitonin, double staining with anti-GalC/SUL and anti-NeuN antibodies was also possible throughout the entire depth of tissue sections (Fig. 7C and Supplementary Movie 3).

3.5. The effect of digitonin on GalC/SUL immunoreactivity in tissue sections of adult mouse brains

Our results indicate that the distribution patterns of GalC/SUL in P8 mouse brains can be examined by immunofluorescent staining using digitonin. We also tested whether our method is applicable to GalC/SUL immunostaining of adult mouse cerebral cortices. We stained brain sections of adult mice with anti-GalC/SUL antibody using various concentrations of digitonin and examined the immunoreactivity in superficial (layer II/III) and deep (layers V-VI) cortical layers using confocal microscopy (Fig. 8). In superficial cortical layers, GalC/SUL immunoreactivity at the middle of the sections was almost invisible in control DMSO-treated samples (Fig. 8B, DMSO). When sections were treated with digitonin, we found that GalC/SUL immunoreactivity was augmented by digitonin in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 8B, Digitonin). Consistently, when immunofluorescence intensities were measured and plotted against the depth in the sections as in Fig. 6B, the valleys of the intensity-depth plots at the middle of sections became markedly shallower in a manner dependent on digitonin concentration (Fig. 8D). A digitonin concentration of 250 µg/ml was required for efficient visualization of GalC/SUL immunoreactivity at the middle of sections (Fig. 8B and D). This concentration of digitonin is higher than that optimal for P8 sections. This result is consistent with our previous observations that higher concentrations of digitonin are required for detecting various proteins such as calbindin D, neurofilament M and Islet-1/2 in the sections of adult mouse brains (Matsubayashi et al., 2008).

Fig. 8.

The effect of digitonin on GalC/SUL immunoreactivity in sections from adult mouse brains. Fixed brains of adult mice were dissected out, and coronal sections of cerebral cortices were made using a vibratome. The sections were stained with anti-GalC/SUL antibody using either 1% DMSO or 60–500 µg/ml digitonin. The sections were also counterstained with Hoechst 33342. (A) Low magnification images of Hoechst staining. (B and C) High magnification confocal images of GalC/SUL immunostaining in the boxed areas in (A). Superficial (B) and deep (C) cortical layers were examined. XY-optical sections at the middle of the brain section and XZ-optical sections reconstructed along white solid lines (black arrowheads) are displayed as in Fig. 7A. White dashed lines (black arrows) indicate the vertical position of the displayed XY-optical sections. Note that GalC/SUL immunoreactivity was enhanced by digitonin only in superficial layers of the cerebral cortex (compare B and C). (D and E) Relationships between fluorescence intensities and depth in superficial (D) and deep (E) layers of the cerebral cortex. Fluorescence intensities inXZ-maximum projection images are plotted against the depth in tissue sections and displayed as in Fig. 6B. Note that the valleys at the middle of DMSO-treated tissues (light blue circles) were shallowed by digitonin (light green triangles, dark green triangles, orange squares and red squares) only in superficial layers of the cortex (D). Cc, corpus callosum; St, striatum. Scale bars = 500 µm (A); 50 µm (Band C).

In deep cortical layers, however, it was difficult to visualize GalC/SUL-positive structures, and the valleys of the intensity-depth plots were not improved even using 500 µg/ml digitonin (Fig. 8C and E). Our further efforts, such as extending incubation time or altering concentrations of the primary antibody, did not lead to better GalC/SUL immunoreactivity (data not shown). Currently, we do not know the reason why digitonin did not enhance GalC/SUL immunoreactivity in deep cortical layers of adult brains. These results suggest that although digitonin is able to improve GalC/SUL immunoreactivity in adult brain tissues, its effectiveness varies depending on the type of tissue to be analyzed.

3.6. The effect of digitonin on O4 immunoreactivity

To examine whether our method is applicable for the detection of not only GalC/SUL but also other antigens that are vulnerable to permeabilizing reagents, we then assayed the effect of digitonin on O4 immunoreactivity. O4 antibody recognizes multiple antigens expressed by OLs and OPCs including SUL and a hitherto unidentified molecule(s) POA (Sommer and Schachner, 1981; Bansal et al., 1989; Bansal et al., 1992). Importantly, O4 immunoreactivity is degraded by acetone (Sommer and Schachner, 1981) or Triton X-100 (our unpublished results). We stained P8 mouse brain sections with O4 antibody using BSA/PBS, DMSO or 60–250 µg/ml digitonin. Although O4 immunoreactivity was clearly detected at the surface of BSA/PBS-, DMSO-treated sections, that in digitonin-treated sections was greatly reduced even at a concentration of 60 µg/ml (Fig. 9A and B). The immunoreactivity almost completely disappeared when sections were treated with higher concentrations (120 and 250 µg/ml) of digitonin (Fig. 9A and B). Therefore, O4 immunoreactivity might be more susceptible to digitonin than GalC/SUL immunoreactivity. Even though digitonin at concentrations of less than 60 µg/ml could be compatible with O4 immunostaining, we did not examine this point, because more than 60 µg/ml digitonin is necessary for efficient detection of nuclear NeuN immunoreactivity at the middle of sections. These results suggest that the effect of digitonin can vary according to the lipid antigen, and therefore digitonin treatment may not be an appropriate method for examining some lipids.

Fig. 9.

The effect of digitonin on O4 immunoreactivity. Fixed brains of P8 mice were dissected out, and coronal sections of cerebral cortices were made using a vibratome. The sections were stained with O4 antibody using 60–250 µg/ml digitonin. (A) Low magnification images. (B) High magnification images of the areas indicated by white squares in (A). Note that O4 immunoreactivity was significantly reduced by digitonin treatment. Scale bars = 500 µm (A); 50 µm (B).

4. Discussion

The results presented here demonstrate that by using digitonin as a detergent, endogenous GalC/SUL in fixed brain sections can be successfully visualized by immunofluorescent staining. Our confocal images show that digitonin permeabilization markedly enhances antibody penetration into brain sections without disrupting GalC/SUL immunoreactivity and enables clear visualization of GalC/SUL+ cells and structures buried in the middle of tissue sections. Digitonin treatment is especially effective when brain sections from juvenile mice are used.

4.1. Application of digitonin treatment to immunostaining for other lipid molecules

We have shown that digitonin is useful for visualizing the distribution of endogenous GalC/SUL in fixed brain sections. It will be important to investigate whether digitonin also allows for the visualization of the distribution patterns of other lipid antigens in brain sections. A recent study showed that digitonin treatment preserved the subcellular localization of an endogenous lipid antigen, phosphatidyl inositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2], which was found to be localized at the leading edge of HL-60 cells (Sharma et al., 2008). In addition, previously we showed that digitonin treatment was compatible with the lipophilic neuronal tracer DiI and reported a double-labeling method with fluorescent immunostaining and DiI neuronal tracing using digitonin (Matsubayashi et al., 2008). These results suggest that digitonin treatment should be tested as a possible candidate method for detecting other lipid antigens in tissue sections using immunostaining. On the other hand, in this paper we showed that O4 immunoreactivity was degraded by digitonin treatment, suggesting that some kinds of lipid molecules may not be compatible with digitonin treatment. It would be useful to find out rules to predict whether or not digitonin treatment preserves the localization of certain lipid molecules based on their molecular structures.

4.2. Concentration-dependent effects of digitonin

The results in Fig. 7 suggest that the nuclear envelope, which is supposed to be one of the most resistant cellular membranes to digitonin (Elias et al., 1978; Adam et al., 1990), is sufficiently permeabilized by 120 µg/ml digitonin in fixed brain sections from juvenile mice. This implies that all cellular membranes should be permeabilized by this concentration of digitonin. Therefore, when GalC/SUL is to be immunostained, increasing the concentration of digitonin over 120 µg/ml would only increase the risk of degradation of GalC/SUL immunoreactivity, with little additive enhancement of tissue permeability.

Our results suggest that the sensitivities to digitonin treatment are different between O4+CC1− cells and O4+CC1+ cells. GalC/SUL immunoreactivity on O4+CC1− cells disappeared after treatment with relatively lower concentrations of digitonin, whereas that on O4+CC1+ cells and MBP+ myelin was more stable even in the presence of higher concentrations (250–500 µg/ml) of digitonin (Fig. 5). Currently, we do not know the reason for their distinct sensitivities to digitonin, but these results suggest that the sensitivities to digitonin are different depending on cell types and structures to be visualized. In addition, we showed that the effectiveness of digitonin could be different depending on the tissues analyzed (Fig. 8). Therefore, when using different tissues or other lipid antigens, it would be recommended to determine an appropriate concentration of digitonin that efficiently permeabilizes tissue sections while at the same time preserving GalC/SUL immunoreactivity.

4.3. Permeabilization of fixed brain tissues using a cholesterol-specific detergent

Currently, Triton X-100 is widely used to enhance antibody penetration into brain sections during immunostaining procedures. Methanol and ethanol are also used occasionally for this purpose. Although these reagents efficiently improve the penetration of antibodies into tissue sections, they solubilize a wide variety of lipids almost indiscriminately (Schuck et al., 2003), and therefore lipid antigens are often difficult to detect when these reagents are used for immunostaining. This problem could be resolved by using detergents which selectively interact with specific lipid molecules. It is conceivable that such selective detergents would preferentially affect specific types of target lipids only, preserving the distribution of most other lipids. Consistently, our results showed that GalC/SUL immunoreactivity was well-preserved even after treatment with digitonin, a cholesterol-specific detergent. Furthermore, we previously showed that the DiI signals were not significantly affected by digitonin treatment (Matsubayashi et al., 2008). It would be extremely useful if various detergents with distinct target specificities were to become available.

4.4. Localization of GalC in vivo

Previously, the expression level and the distribution of GalC have been examined mainly using cultured OLs (Raff et al., 1978; Mirsky et al., 1980; Ranscht et al., 1982). A previous report, however, showed that the expression level of GalC in Schwann cells rapidly changed with time in culture (Mirsky et al., 1980), suggesting that the expression level of GalC in cultured cells could be different from that in vivo. It is therefore desirable to examine the expression level and the distribution pattern of GalC in tissue sections. However, it was not easy to investigate the detailed expression patterns of GalC in fixed tissue sections, probably because detergent treatment resulted in the extraction of GalC from OLs (Reynolds and Wilkin, 1988). We have succeeded in overcoming this problem by utilizing the cholesterol-specific detergent digitonin for tissue permeabilization. Our method should enable investigation of the detailed expression patterns and the subcellular localization of GalC in the brain.

The involvement of GalC and anti-GalC antibody in pathological conditions has been reported. It has been shown that Krabbe disease (also known as globoid cell leukodystrophy) is caused by the impairment of GalC-catalyzing enzyme galactocerebrosidase activity (Suzuki and Suzuki, 1971). In Krabbe disease, GalC was reported to accumulate in vivo. GalC is also involved in demyelinating diseases. Anti-GalC autoantibody was detected in patients with post-infectious encephalitis and Guillain–Barré syndrome (Kusunoki et al., 1995; Nishimura et al., 1996). Furthermore, anti-GalC anti body was reported to trigger experimental allergic neuritis (Saida et al., 1979). In addition, a possible role for GalC in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) entry into neural cells and mucosal epithelium was reported (Harouse et al., 1991; Alfsen and Bomsel, 2002). Our staining method using digitonin should enable to examine the precise localization of GalC in these pathological conditions, especially in the tissues from young patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Barbara Ranscht (The Burnham Institute) for kindly providing anti-GalC/SUL antibody. We thank Kaori Tanno for her excellent technical assistance and Zachary Blalock for reading our manuscript. We are grateful to Drs. Shoji Tsuji (The University of Tokyo), Haruhiko Bito (The University of Tokyo) and Kawasaki lab members for helpful discussion and support. This work was supported by the 21st century COE program “Center for Integrated Brain Medical Sciences” from MEXT, Global COE program “Comprehensive Center of Education and Research for Chemical Biology of the Diseases” from MEXT, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas-Elucidation of neural network function in the brain from MEXT, PRESTO from Japan Science and Technology Agency and Human Frontier Science Program. This work was also supported by Uehara Foundation and Kanae Foundation.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.11.018.

References

- Adam SA, Marr RS, Gerace L. Nuclear protein import in permeabilized mammalian cells requires soluble cytoplasmic factors. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:807–816. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.3.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfsen A, Bomsel M. HIV-1 gp41 envelope residues 650–685 exposed on native virus act as a lectin to bind epithelial cell galactosyl ceramide. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25649–25659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal R, Stefansson K, Pfeiffer SE. Proligodendroblast antigen (POA), a developmental antigen expressed by A007/O4-positive oligodendrocyte progenitors prior to the appearance of sulfatide and galactocerebroside. J Neurochem. 1992;58:2221–2229. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal R, Warrington AE, Gard AL, Ranscht B, Pfeiffer SE. Multiple and novel specificities of monoclonal antibodies O1, O4, and R-mAb used in the analysis of oligodendrocyte development. J Neurosci Res. 1989;24:548–557. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490240413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat RV, Axt KJ, Fosnaugh JS, Smith KJ, Johnson KA, Hill DE, et al. Expression of the APC tumor suppressor protein in oligodendroglia. Glia. 1996;17:169–174. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199606)17:2<169::AID-GLIA8>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittner MA, Holz RW. Effects of tetanus toxin on catecholamine release from intact and digitonin-permeabilized chromaffin cells. J Neurochem. 1988;51:451–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosio A, Binczek E, Stoffel W. Functional breakdown of the lipid bilayer of the myelin membrane in central and peripheral nervous system by disrupted galactocerebroside synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13280–13285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee T, Fujita N, Dupree J, Shi R, Blight A, Suzuki K, et al. Myelination in the absence of galactocerebroside and sulfatide: normal structure with abnormal function and regional instability. Cell. 1996;86:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis R, Cohen J, Fok-Seang J, Hanley MR, Gregson NA, Reynolds R, et al. Development of macroglial cells in rat cerebellum I Use of antibodies to follow early in vivo development and migration of oligodendrocytes. J Neurocytol. 1988;17:43–54. doi: 10.1007/BF01735376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupree JL, Coetzee T, Blight A, Suzuki K, Popko B. Myelin galactolipids are essential for proper node of Ranvier formation in the CNS. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1642–1649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-05-01642.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer CA, Benjamins JA. Glycolipids and transmembrane signaling: antibodies to galactocerebroside cause an influx of calcium in oligodendrocytes. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:625–633. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer CA, Benjamins JA. Organization of oligodendroglial membrane sheets: II Galactocerebroside: antibody interactions signal changes in cytoskeleton and myelin basic protein. J Neurosci Res. 1989;24:212–221. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490240212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias PM, Goerke J, Friend DS, Brown BE. Freeze-fracture identification of sterol-digitonin complexes in cell and liposome membranes. J Cell Biol. 1978;78:577–596. doi: 10.1083/jcb.78.2.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geelen MJ. The use of digitonin-permeabilized mammalian cells for measuring enzyme activities in the course of studies on lipid metabolism. Anal Biochem. 2005;347:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour MS, Skoff RP. Expression of galactocerebroside in developing normal and jimpy oligodendrocytes in situ . J Neurocytol. 1988;17:485–498. doi: 10.1007/BF01189804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogelein H, Huby A. Interaction of saponin and digitonin with black lipid membranes and lipid monolayers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;773:32–38. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(84)90547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R, Reynolds R. Proliferation and differentiation potential of rat fore-brain oligodendroglial progenitors both in vitro and in vivo . Development. 1991;111:1061–1080. doi: 10.1242/dev.111.4.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harouse JM, Bhat S, Spitalnik SL, Laughlin M, Stefano K, Silberberg DH, et al. Inhibition of entry of HIV-1 in neural cell lines by antibodies against galactosyl ceramide. Science. 1991;253:320–323. doi: 10.1126/science.1857969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Mizuseki K, Nishikawa S, Kaneko S, Kuwana Y, Nakanishi S, et al. Induction of midbrain dopaminergic neurons from ES cells by stromal cell-derived inducing activity. Neuron. 2000;28:31–40. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp PE, Skoff RP, Sprinkle TJ. Differential expression of galactocerebroside, myelin basic protein, and 2’,3’cyclic nucleotide 3’phosphohydrolase during development of oligodendrocytes in vitro . J Neurosci Res. 1988;21:249–259. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490210217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause F. Detection and analysis of protein-protein interactions in organellar and prokaryotic proteomes by native gel electrophoresis: (Membrane) protein complexes and supercomplexes. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:2759–2781. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusunoki S, Chiba A, Hitoshi S, Takizawa H, Kanazawa I. Anti-Gal-C antibody in autoimmune neuropathies subsequent to mycoplasma infection. Muscle Nerve. 1995;18:409–413. doi: 10.1002/mus.880180407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind D, Franken S, Kappler J, Jankowski J, Schilling K. Characterization of the neuronal marker NeuN as a multiply phosphorylated antigen with discrete subcellular localization. J Neurosci Res. 2005;79:295–302. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu QR, Sun T, Zhu Z, Ma N, Garcia M, Stiles CD, et al. Common developmental requirement for Olig function indicates a motor neuron/oligodendrocyte connection. Cell. 2002;109:75–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus J, Popko B. Galactolipids are molecular determinants of myelin development and axo-glial organization. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1573:406–413. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi Y, Fukuda M, Nishida E. Evidence for existence of a nuclear pore complex-mediated, cytosol-independent pathway of nuclear translocation of ERK MAP kinase in permeabilized cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41755–41760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi Y, Iwai L, Kawasaki H. Fluorescent double-labeling with carbocyanine neuronal tracing and immunohistochemistry using a cholesterol-specific detergent digitonin. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;174:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RH. Regulation of oligodendrocyte development in the vertebrate CNS. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;67:451–467. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirsky R, Winter j, Abney ER, Pruss RM, Gavrilovic J, Raff MC. Myelin-specific proteins and glycolipids in rat Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes in culture. J Cell Biol. 1980;84:483–494. doi: 10.1083/jcb.84.3.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monge M, Kadiiski D, Jacque CM, Zalc B. Oligodendroglial expression deposition of four major myelin constituents in the myelin sheath during development An in vivo study. Dev Neurosci. 1986;8:222–235. doi: 10.1159/000112255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen RJ, Buck CR, Smith AM. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development. 1992;116:201–211. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura M, Saida T, Kuroki S, Kawabata T, Obayashi H, Saida K, et al. Post-infectious encephalitis with anti-galactocerebroside antibody subsequent to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. J Neurol Sci. 1996;140:91–95. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(96)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton WT, Autilio LA. The lipid composition of purified bovine brain myelin. J Neurochem. 1966;13:213–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1966.tb06794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsaki Y, Maeda T, Fujimoto T. Fixation and permeabilization protocol is critical for the immunolabeling of lipid droplet proteins. Histochem Cell Biol. 2005;124:445–452. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer SE, Warrington AE, Bansal R. The oligodendrocyte and its many cellular processes. Trends Cell Biol. 1993;3:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(93)90213-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff MC. Glial cell diversification in the rat optic nerve. Science. 1989;243:1450–1455. doi: 10.1126/science.2648568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff MC, Mirsky R, Fields KL, Lisak RP, Dorfman SH, Silberberg DH, et al. Galactocerebroside is a specific cell-surface antigenic marker for oligodendrocytes in culture. Nature. 1978;274:813–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranscht B, Clapshaw PA, Price J, Noble M, Seifert W. Development of oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells studied with a monoclonal antibody against galactocerebroside. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:2709–2713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.8.2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds R, Wilkin GP. Development of macroglial cells in rat cerebellum II An in situ immunohistochemical study of oligodendroglial lineage from precursor to mature myelinating cell. Development. 1988;102:409–425. doi: 10.1242/dev.102.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saida T, Saida K, Dorfman SH, Silberberg DH, Sumner AJ, Manning MC, et al. Experimental allergic neuritis induced by sensitization with galactocerebroside. Science. 1979;204:1103–1106. doi: 10.1126/science.451555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck S, Honsho M, Ekroos K, Shevchenko A, Simons K. Resistance of cell membranes to different detergents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5795–5800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631579100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz A, Futerman AH. Immunolocalization of gangliosides by light microscopy using anti-ganglioside antibodies. Methods Enzymol. 2000;312:179–187. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)12908-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma VP, Des Marais V, Sumners C, Shaw G, Narang A. Immunostaining evidence for PI(4,5)P2 localization at the leading edge of chemoattractant-stimulated HL-60 cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:440–447. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer I, Schachner M. Monoclonal antibodies (O1 to O4) to oligodendrocyte cell surfaces: an immunocytological study in the central nervous system. Dev Biol. 1981;83:311–327. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffel W, Bosio A. Myelin glycolipids and their functions. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:654–661. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Suzuki K. Krabbe’s globoid cell leukodystrophy: deficiency of galactocerebrosidase in serum, leukocytes, and fibroblasts. Science. 1971;171:73–75. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3966.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda T, Hayakawa I, Matsubayashi Y, Tanaka K, Ikenaka K, Lu QR, et al. Termination of lesion-induced plasticity in the mouse barrel cortex in the absence of oligodendrocytes. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;39:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrington AE, Pfeiffer SE. Proliferation and differentiation of O4+ oligodendrocytes in postnatal rat cerebellum: analysis in unfixed tissue slices using anti-glycolipid antibodies. J Neurosci Res. 1992;33:338–353. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490330218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin M, Yue T, Ma Z, Wu FF, Gow A, Lu QR. Myelinogenesis and axonal recognition by oligodendrocytes in brain are uncoupled in Olig1-null mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1354–1365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3034-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Anderson DJ. The bHLH transcription factors OLIG2 and OLIG1 couple neuronal and glial subtype specification. Cell. 2002;109:61–73. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.