Abstract

Orbital sclerosing inflammation is a distinct group of pathologies characterized by indolent growth with minimal or no signs of inflammation. However, contrary to earlier classifications, it should not be considered a chronic stage of acute inflammation. Although rare, orbital IgG4-related disease has been associated with systemic sclerosing pseudotumor-like lesions. Possible mechanisms include autoimmune and IgG4 related defective clonal proliferation. Currently, there is no specific treatment protocol for IgG4-related disease although the response to low dose steroid provides a good response as compared to non-IgG4 sclerosing pseudotumor. Specific sclerosing inflammations (e.g. Wegener's disease, sarcoidosis, Sjogren's syndrome) and neoplasms (lymphoma, metastatic breast carcinoma) should be ruled out before considering idiopathic sclerosing inflammation as a diagnosis.

Keywords: IgG4, Inflammation, Neoplasm, Orbit, Sclerosing

INTRODUCTION

Sclerosis is a Greek word meaning hardening of a structure or tissue. This hardening is due to an increase in the fibrous component of the tissues and is always pathological. In the orbit, sclerosing pathology is rare, and therefore, has a limited differential diagnosis.

The narrow spectrum of orbital sclerosing lesions can be etiologically classified, as follows:

Inflammatory - Idiopathic includes IgG4 orbitopathy; auto-immune includes Wegener's granulomatosis, Sarcoidosis, and Sjogren's syndrome (SS)

Neoplastic - Primary includes sclerosing lymphoma, and secondary causes mainly include metastatic sclerosing carcinoma of breast or sclerosing lymphoma

Others - Thyroid orbitopathy (long standing).

There is no clear demarcation among clinical presentations and they can overlap. A detailed clinical history is important to predict the nature of the lesion. Imaging is often inconclusive for a definitive diagnosis. Histopathological features may be non-specific or inconclusive but are currently considered the gold standard for diagnosing sclerosing lesions.

SPECTRUM

(1) Inflammatory sclerosing lesions of the orbit

(i) Idiopathic sclerosing inflammation of the orbit

A small subset of orbital inflammation (about 5% of nonthyroid orbital inflammation) belongs to this group.1 This is considered a separate clinical entity which is distinguished from other orbital inflammatory lesions by the presence of indolent and chronic (over 4 weeks) pauci-cellular lymphocytic inflammation and dense fibrosis.1,2,3 There is no age predilection.2 The presentation may be unilateral or bilateral and usually asymmetrical.1 Lacrimal gland fossa is the most common foci of origin, although it may begin as myositis or retrobulbar apical mass (20%) and this apical lesion can be the sole presentation in 60% of cases.1,3,4 Apical lesion has a tendency to infiltrate the optic nerve initially and therefore, presents with early diminution of vision.3 Other clinical features caused by chronic mild inflammation (e.g., lid edema, dull pain, redness) include, mass effect (proptosis, ptosis, limitation of extraocular movements) and cicatrization (restriction of extraocular movements, ptosis).1,2,3,5 Due to the progressive nature of the lesion it may present as diffuse orbital involvement or with extra-orbital involvement (intracranial, pterigopalatine, or infratemporal fossa).1,5 Although the etiology remains unknown, an underlying immunological mechanism has been suggested.1,6 Elevated levels of IgG4 in serum (>135 mg/dl) and tissue (IgG4/IgG-positive plasma cells ratio >40% and >10 IgG4-positive plasma cells/HPF), have been detected in some patients with sclerosing inflammation of the orbit.7,8,9,10,11 Elevated IgG4, which is normally the least common (3–6% of total serum IgG), may be associated with systemic lesions as discussed earlier. Serum IgG4 level may be elevated (60–70% cases), normal (<40% cases) or low in IgG4 related diseases.8,11,12,13 Recently, prozone phenomenon has been proposed as an explanation for the falsely low IgG4 in some biopsy proven cases of IgG4 related disease.14 This technical error can be minimized by diluting the sample before nephelometry.13 IgG4 related disease (IgG4-RD) is a recently introduced sub-category of sclerosing inflammation which encompasses orbital as well as a wide spectrum of systemic autoimmune or lymphoproliferative diseases.2,8,11,15 Orbital IgG4-RD constitutes about 25% of idiopathic orbital inflammation.16 Systemically, there may be associated type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, Riedel fibrous thyroiditis, sclerosing mediastinitis, interstitial pneumonitis, pericarditis, aortitis or aortic dissection, sclerosing cholangitis, lymphadenitis (non-tender, rubbery nodes), sialadenitis/Mickulicz disease (lacrimal, parotid and/or submandibular gland enlargement)/Kuttner's tumor (unilateral or bilateral submandibular gland enlargement), tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN), meningitis, destructive disease of middle ear/and nose, erythematous/flesh-colored plaques/papules on head and peripheral perineuritis.1,2,5,8,16,17,18 Atopy or allergic manifestations may occur in 50% of patients with IgG4-RD.16 Fever and constitutional symptoms are usually absent.19 The risk of lymphoma (NHL) and carcinoma of the affected organ have been reported.8,19 Autoimmunity and defective immune expression have been described as the underlying mechanism.20 Serum IgG4 level can be used as a rough guide to monitor disease progression (increase in IgG4 level) or response to immunosuppressive therapy (decrease in IgG4 level) during follow-up.8 Flow cytometry blood plasmablasts count (total or IgG4+ plasmablasts) is considered a more useful biomarker for this purpose.8,13 Serum IgE, peripheral eosinophil count, and ESR may be elevated, whereas serum C3 and C4 concentrations are usually low (especially in association with TIN).8 These biomarkers can be used to assess response during follow-up. Histologically, orbital IgG4-RD has a non-glandular origin and there is an absence of oblitrative fibrosis unlike systemic IgG4-related lesions.21 Storiform (swirling) fibrosis or cartwheel arrangement of fibroblasts with tissue eosinophilia is considered an important feature of IgG4 related disease.7,8 The orbit is likely the most common site of involvement in IgG4-RD.16 Orbital IgG4-RD is usually bilateral (48%) and there is no gender predominance unlike systemic IgG4-RD (other than the head-neck site) where middle aged or elderly males are predominantly affected [Figures 1 and 2].7,8,12 Within the orbit, the lacrimal gland is the most commonly affected structure, though it can affect any orbital structure.7,22 Infraorbital nerve involvement and spread of the lesion along the trigeminal nerve has been also described.16,23 The Japanese and Chinese races are genetically predisposed to IgG4-RD.20 Radiologically, all sclerosing inflammation of the orbit appears as a homogenously enhancing mass with irregular margins with typically decreased signal intensity on T2-weighted (T2w) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This is unlike other inflammatory diseases where the signal intensity is generally low on T1w MRI and variable on T2w MRI.1,2,5 Calcification has been reported in one case.6 Comprehensive clinical diagnostic criteria for diagnosing IgG4-RD has been introduced which includes a clinical lesion, serum IgG4 and histologically proven lymphocytes with fibrosis, or IgG4+ plasma cells.11,24 Biopsy is usually required to confirm the diagnosis before starting steroid therapy, as lymphoma or paraneoplastic lesions may also improve after steroid therapy.5,24 18-fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography scan can detect involved foci and disease activity particularly for deep seated lesions where the biopsy is not feasible.15 It can help to determine the most active lesion and therefore, the most productive site for biopsy.25 Due to the indolent nature, the response to the systemic steroid is suboptimal, unlike nonsclerosing pseudotumor.1,6 Early aggressive immunosuppressive chemotherapy (a/c to Kennerdell)6 with or without steroids or radiotherapy results in the clinical improvement, especially mitigating visual loss.2,3,5 There are convincing results of using nonsteroidal immunosuppresants (cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, rituximab) with or without steroids.3,21 In cases, such as IgG4 orbitopathy, where response to systemic steroid is generally good particularly during early stage disease when fibrosis is not excessive, nonsteroidal immunosuppresants (e.g., azathioprine, 2 mg/kg/day or mycophenolate mofetil, 1 g twice a day up to a maximum dose of 2.5 g/day) may be required along with maintenance steroid therapy to prevent recurrence.7,8,21 The relapse rate after discontinuation of steroid is 30–40%.20 There is no standard protocol for an oral steroid in IgG4-RD. Oral prednisolone can be started at an initial dose of 40 mg/day or 0.6 mg/kg/day into three divided doses, with tapering by 10% every 2 weeks up to a final maintenance dose of 5–10 mg per day for at least 2–3 months. Usually, the clinical, radiological, and/or serological response is seen after 2–4 weeks of starting treatment.8,15 If there is no response to therapy, an alternate diagnosis should be considered.24 Response to rituximab (1 g intravenously every 15 days for a total of two doses) is immediate; however, recurrence has been reported after stopping this therapy.8,21 Theoretically, rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) depletes the pool of IgG4-producing B-cells so recurrence should be rare. Its main role is as a steroid sparing agent and steroid tapering agent (in cases where it is difficult to taper the steroid dose below 10 mg/kg/day).8 Due to the apical location or progressive, diffuse and infiltrative nature, surgical resection is not feasible except in rarely localized cases.3,10,26 Spontaneous resolution has been documented in about 30% of IgG-RD.20

Figure 1.

Bilateral proptosis with frozen globe (complete restriction of ocular movements) in a middle aged female with IgG4-related orbitopathy

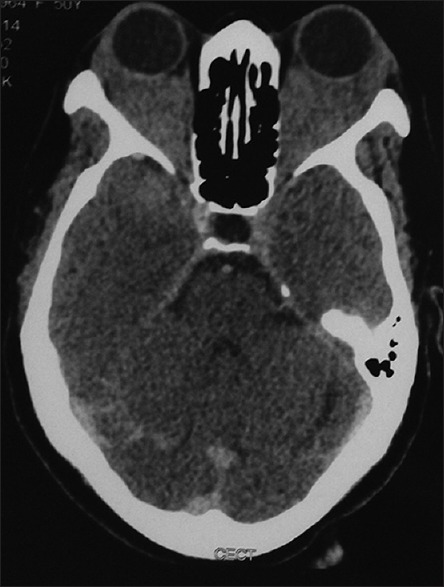

Figure 2.

Computed tomography (axial section) of the same patient in Figure 1 showing bilateral diffuse infiltrating lesion of the orbits, sparing bone

(ii) Autoimmune inflammation of the orbit

(a) Wegener granulomatosis

Clinically, patients with Wegener disease may present as an isolated ophthalmic presentation or with sinus involvement and systemic disease.27 c-ANCA is a serum marker which is elevated in systemic disease (90% cases) more so than limited disease (32% cases).5 Ophthalmic involvement occurs in about 50% of Wegener's cases which may present as uveitis, scleritis (15% of all scleritis cases), or orbital cellulitis (18–22% Wegener's cases).5,27 Orbital cellulitis may mimic either nonspecific inflammatory lesions or IgG4 orbitopathy. Abundant IgG4 plasma cells may mislead pathologists evaluating cases of Wegener disease.21

(b) Sarcoidosis

Ophthalmic involvement (up to 50%) may occur as conjunctivitis, uveitis, optic neuritis, or orbital cellulitis. Noncaseating granulomas on biopsy raised serum ACE level, and the presence of hilar lymphadenopathy or interstitial lung disease (up to 90%) are salient features for differentiation from other forms of orbital cellulitis.5

(c) Sjogrens syndrome

The presence of dryness (dry eye/dry mouth) and preferential involvement of parotid gland differentiates SS from the two similar diseases, Mickulicz disease and Kuttner's tumor, where gland (lacrimal/salivary) function usually remains normal and submandibular glands are typically involved.16,19 The absence of other associated features of IgG4-RD (e.g. increased the incidence of allergic rhinitis, bronchial asthma, AIP, TIN, dramatic response to steroid) also favors the diagnosis of SS while considering differentials of dacryoadenitis.8,15 Unlike IgG4+ Mikulize disease, male SS patients are rare. High titers of ANA (antinuclear antibody), RF (rheumatoid factor), anti-SSA (Ro), and anti-SSB (La) antibodies without increased serum IgG4 or tissue IgG4+ plasma cells rules out IgG4-RD.15

(2) Sclerosing neoplasms of orbit

These lesions are usually metastatic, mostly unilateral, rapidly growing, and occur in the elderly.28 The presentation can mimic idiopathic sclerosing orbital inflammation or IgG4-RD, a mass lesion, an infiltrative lesion, inflammatory lesion, or functional deficit due to cranial nerve/orbital apex involvement.1 In cases of occult/unknown primary, an open biopsy with IHC is required to establish tissue diagnosis and plan chemotherapy/radiotherapy unlike steroid treatment for IgG4-RD.1,28

(i) Sclerosing lymphoma

Metastatic lymphoma is more aggressive (i.e., high grade) as compared to primary orbital lymphoma, and usually B-cell NHL type and mostly unilateral.1,3,28 Unlike other orbital metastases, the presentation of metastatic lymphoma may be slow, painless proptosis.28 Marginal zone lymphomas contain IgG4+ plasma cells similar to IgG4-RD. Fluorescence in situ hybridization for light chain (FISH) and Southern blot technique (for heavy chain) can differentiate the two entities.21 Chronic nodular sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma has been reported from the orbit. The presence of Reed Sternberg cells (RS-cells) easily establishes the diagnosis.29

(ii) Sclerosing carcinoma of breast

Breast cancer constitutes more than 50% cases of orbital metastasis.28 Approximately 75% of the cases have known primary and non-orbital metastasis before or at the time of orbital presentation.3 The usual presentation is an infiltrative orbital mass with the restriction of extraocular movements mimicking IgG4-RD. Differentiating clinical features in favor of metastasis includes positive history, breast lump, progressive enophthalmos (25% cases), response to hormone therapy, and a diffuse lesion that tends to proliferate along the rectus muscles.28

OTHER DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

(1) Mesenchymal lesions of soft tissue or boney

-

(i)

Fibrohistiocytic neoplasm

-

(ii)

Nodular fasciitis

-

(iii)

Fibromatosis

-

(iv)

Fibrosarcoma

-

(v)

Giant cell angiofibroma

-

(vi)

Rhabdomyosarcoma

-

(vii)

Leiomyosarcoma

-

(viii)

Leiomyosarcoma

-

(ix)

Alveolar soft part sarcoma.

(2) Vascular tumor

-

(i)

Hemangiopericytoma.

(3) Neurogenic tumors

-

(i)

Diffuse neurofibroma

-

(ii)

Granular cell tumor.

(4) Granulomatous inflammations

-

(i)

Infections

-

(a)Fungal

-

(b)Tubercular.

-

(a)

-

(ii)

Histiocytosis-X

-

(iii)

Erdheim–Chester disease

A systemic nonLangerhans histiocytic xanthogranulomatous inflammation with foamy cells, Touton giant cells, fibrosis with CD 68 positivity on IHC.5

-

(iv)

Autoimmune-Churg–Strauss syndrome

The disease presents as a systemic necrotizing vasculitis with eosinophilia (blood and tissue), raised serum IgE and asthma. The presence of p-ANCA antibody in serum strongly supports diagnosis.5

-

(v)

Tolosa-Hunt syndrome

This is characterized by unilateral (mostly) painful ophthalmoplegia due to granulomatous lesion at or near the orbital apex that responds dramatically to high dose steroid therapy.5

(5) Kimura's disease

(6) Orbital myositis

Orbital myositis is the most common form of idiopathic orbital inflammatory disease which usually responds to high dose oral steroid. However, some cases may be unresponsive and require non-steroidal immunosuppressive agents or even radiotherapy.3 The pathology is possibly autoimmune and auto-antibodies against eye muscle membrane protein have been identified.30 Biopsy is rarely required to rule out other differentials (e.g., fungal, metastasis), especially in cases where the response to steroid is poor.5 The disease is mostly unilateral and females are more commonly affected.3,5 The signs of inflammation (pain, erythema, swelling, tenderness) are significantly correlated to the severity of proptosis, unlike sclerosing orbital inflammation discussed earlier.1

(7) Thyroid orbitopathy related fibrosis

(8) Congenital

-

(i)

Congenital fibrosis of extraocular muscles

(9) Trauma

(10) Rare sclerosing lesions

-

(i)

Sclerosing lacrimal gland tumors.

SPA resembles low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma/adenocarcinoma. The lesion is usually well-defined and partly encapsulated with preserved lobular architecture. Estrogen and progesterone receptors have been identified on the tumor to distinguish SPA from other lacrimal gland carcinomas.

-

(a)

Sclerosing polycystic adenosis (SPA)31

-

(b)

Sclerosing variety of adenoid cystic carcinoma.

This lesion may be idiopathic or secondary to subtenon steroid injection, infection, trauma, or sinonasal surgery (due to ointment/gauze).

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rootman J. 2nd ed. Vol. 156. USA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2003. Diseases of the Orbit: A Multidisciplinary Approach; pp. 455–506. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorne JE, Volpe NJ, Wulc AE, Galetta SL. Caught by a masquerade: Sclerosing orbital inflammation. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:50–4. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu CH, Ma L, Ku WJ, Kao LY, Tsai YJ. Bilateral idiopathic sclerosing inflammation of the orbit: Report of three cases. Chang Gung Med J. 2004;27:758–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abramovitz JN, Kasdon DL, Sutula F, Post KD, Chong FK. Sclerosing orbital pseudotumor. Neurosurgery. 1983;12:463–8. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198304000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon LK. Orbital inflammatory disease: A diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Eye (Lond) 2006;20:1196–206. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zakir R, Manners RM, Ellison D, Barker S, Crick M. Idiopathic sclerosing inflammation of the orbit: A new finding of calcification. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1322–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.11.1318f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stone JH, Zen Y, Deshpande V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:539–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1104650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haralampos MM, Fragoulis GE, Sone JH. Overview of IgG4-Related Disease. Up To Date. 2013. Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-igg4-related-disease .

- 9.Umehara H, Okazaki K, Masaki Y, Kawano M, Yamamoto M, Saeki T, et al. Comprehensive diagnostic criteria for IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD), 2011. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s10165-011-0571-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fogt F, Wellmann A, Lee V. Immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD) with associated sarcoidosis. J Ocul Biol. 2013;1:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK, Yi EE, Sato Y, Yoshino T, et al. Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1181–92. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du H, Wu Y, Yan L, Wu B, Wan J. IgG4-related disease and the current status of diagnostic approaches. EXCLI J. 2012;11:651–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox RI, Fox CM. IgG4 levels and plasmablasts as a marker for IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1–3. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khosroshahi A, Cheryk LA, Carruthers MN, Edwards JA, Bloch DB, Stone JH. Brief report: Spuriously low serum IgG4 concentrations caused by the prozone phenomenon in patients with IgG4-related disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:213–7. doi: 10.1002/art.38193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masaki Y, Kurose N, Umehara H. IgG4-related disease: A novel lymphoproliferative disorder discovered and established in Japan in the 21st century. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2011;51:13–20. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.51.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone JH. Extra-pancreatic features of autoimmune pancreatitis (IgG4-related disease) Pancreapedia. 2013 DOI: 10.3998/panc.2013.19. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mejico LJ. IgG4-related ophthalmic disease. Saudi J Ophthalmol. 2015;29:53–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohan A, Ravishankar B, Vishwanath S, Vankalakunti M, Kishore B, Ballal HS. IgG4 related renal disease: A wolf in sheep's clothing. Indian J Nephrol. 2014;24:382–6. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.133022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Divatia M, Kim SA, Ro JY. IgG4-related sclerosing disease, an emerging entity: A review of a multi-system disease. Yonsei Med J. 2012;53:15–34. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2012.53.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abud-Mendoza C. IgG4 (IgG4-RD) related diseases, with a horizon not limited to Mikulicz's disease. Reumatol Clin. 2013;9:133–5. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubota T, Moritani S. Orbital IgG4-related disease: Clinical features and diagnosis. ISRN Rheumatol 2012. 2012 doi: 10.5402/2012/412896. 412896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace ZS, Deshpande V, Stone JH. Ophthalmic manifestations of IgG4-related disease: Single-center experience and literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:806–17. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardy TG, McNab AA, Rose GE. Enlargement of the infraorbital nerve: An important sign associated with orbital reactive lymphoid hyperplasia or immunoglobulin g4-related disease. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umehara H, Okazaki K, Stone JH, Kawa S, Kawano M, editors. IgG4-Related Disease. Japan: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma P, Chatterjee P. Contrast-enhanced (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in immunoglobulin G4-related retroperitoneal fibrosis. Indian J Nucl Med. 2015;30:72–4. doi: 10.4103/0972-3919.147551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Su PY, Wu CS, Chang SW. IgG4-related dacryoadenitis. Taiwan J Ophthalmol. 2013;3:116–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abel AD, Carlson JA, Bakri S, Meyer DR. Sclerosing lipogranuloma of the orbit after periocular steroid injection. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1841–5. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00560-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng E, Ilsen PF. Orbital metastases. Optometry. 2010;81:647–57. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2010.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel S, Rootman J. Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin's disease of the orbit. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:1433–6. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34363-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atabay C, Tyutyunikov A, Scalise D, Stolarski C, Hayes MB, Kennerdell JS, et al. Serum antibodies reactive with eye muscle membrane antigens are detected in patients with nonspecific orbital inflammation. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:145–53. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)31066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfeiffer ML, Yin VT, Bell D, Mancini R, Esmaeli B. Sclerosing polycystic adenosis of the lacrimal gland. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:873–873.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall J, Mortimore R, Sullivan T. Sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma of the orbit. Orbit. 2003;22:165–70. doi: 10.1076/orbi.22.3.165.15621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]