Abstract

Background

Young people who engage in substance use are at risk for becoming infected with HIV and diseases with similar transmission dynamics. Effective disease prevention programs delivered by prevention specialists exist but are rarely provided in systems of care due to staffing/resource constraints and operational barriers - and are thus of limited reach. Web-based prevention interventions could possibly offer an effective alternative to prevention specialist-delivered interventions and may enable widespread, cost-effective access to evidence-based prevention programming. Previous research has shown the HIV/disease prevention program within the web-based Therapeutic Education System (TES) to be an effective adjunct to a prevention specialist-delivered intervention. The present study was the first randomized, clinical trial to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of this web-based intervention as a standalone intervention relative to a traditional, prevention specialist-delivered intervention.

Methods

Adolescents entering outpatient treatment for substance use participated in this multi-site trial. Participants were randomly assigned to either a traditional intervention delivered by a prevention specialist (n = 72) or the web-delivered TES intervention (n = 69). Intervention effectiveness was assessed by evaluating changes in participants’ knowledge about HIV, hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections, intentions to engage in safer sex, sex-related risk behavior, self-efficacy to use condoms, and condom use skills.

Findings

Participants in the TES intervention achieved significant and comparable increases in HIV/disease-related knowledge, condom use self-efficacy, and condom use skills and comparable decreases in HIV risk behavior relative to participants who received the intervention delivered by a prevention specialist. Participants rated TES as easier to understand.

Conclusion

This study indicates that TES is as effective as HIV/disease prevention delivered by a prevention specialist. Because technology-based interventions such as TES have high fidelity, are inexpensive and scalable, and can be implemented in a wide variety of settings, they have the potential to greatly increase access to effective prevention programming.

Although the current HIV epidemic differs greatly in various parts of the world, young people are frequently at the center of the epidemic, and HIV has been referred to as a “youth-driven disease”1. HIV/AIDS has become the second leading cause of death worldwide in adolescents, largely driven by the epidemic in Africa2. The majority of HIV infections among American youth are due to sexual transmission (92%), with this age group (13 – 24 years old) constituting 25% of new infections in the U.S.3.

Recent data on HIV infection rates in New York City (the geographical location in which the present study was conducted) suggest recent shifts in demographic trends in infection4. Infection risk now differentially affects younger people belonging to less privileged socioeconomic groups, especially in minority communities. In 2013, the highest percentage (36.3%) of new HIV diagnoses in New York City was for those between 20 and 29 years of age. Those <10% below the federal poverty level (FPL) accounted for only 9.7% of new infections, a rate that jumps to an average of 27.13% across those who are in medium (10% to 20% below the FPL), high (20% to 30% below the FPL), and very high (greater than 30% below the FPL) poverty groups. Blacks (42.8%) and Hispanics (34.4%) accounted for a majority of new infections, with those identifying as white only making up 17.7% of new diagnoses. Young drug-using minorities, especially males who have sex with males (MSM), are the highest risk group in the U.S.

The period of adolescence and young adulthood is often a time of experimentation with alcohol and drugs, which may make youth at particularly high risk for infection with HIV. Indeed, substance use impairs decision-making and is linked with risk for HIV infection more often for youth than for adults. Additionally, some drugs, such as cocaine and amphetamines, heighten sexual arousal and can promote high-risk sexual activity5.

Substance-using youth report having sex at an earlier age, having higher numbers of sexual partners, using condoms less frequently and engaging in different types of risk behavior (e.g., exchanging sex for drugs, money, or shelter) compared to their non-drug-using peers. Additionally, youth who use drugs have been shown to have less HIV-related knowledge, lower perceived susceptibility to HIV, higher levels of impulsivity, and less self-efficacy to engage in preventive behavior. They are also at greater risk of other infectious diseases with similar transmission dynamics, including hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections (STIs)6

These trends underscore the importance of providing youth, and particularly youth involved in substance use, with effective HIV and other infectious disease prevention interventions, and highlight the potential for youth to have a large impact in changing the trajectory of the HIV epidemic. Given that new infections are concentrated among young adults, it is critical for prevention efforts to reach individuals earlier in their life course before they become infected. A number of effective HIV prevention interventions for young people exist, and typically target HIV-related sexual and drug-use behaviors7. Such primary prevention programs are typically designed to increase accurate knowledge about HIV and preventive actions that provide effective deterrents against infection, increase youth’s intentions to reduce risk behavior and communicate about condom use with sex partners, improve attitudes toward condom use and safer sex, increase self-efficacy and ability to effectively use condoms, and reduce perceived invulnerability to HIV, as these variables are strongly predictive of progression to consistent condom use and safer sex as youth get older. Such prevention initiatives can also have positive long-term effects as evidenced by increased condom use and reductions in numbers of sexual partners8–9.

However, few evidence-based interventions are actually provided to youth, even in formal systems, and are thus of limited reach. Accurate HIV prevention knowledge and skills education are also rarely provided to youth who engage in substance use. Only 10% of adolescents who need substance abuse treatment have access to it, and only a minority of adolescent treatment programs integrate effective HIV education10. Additionally, although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have created program materials and training resources to help promote greater adoption of evidence-based prevention interventions in youth community agencies (e.g., Replicating Effective Programs and Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions projects), the majority of teens in community-based substance abuse treatment do not receive evidence-based HIV prevention interventions, and virtually none receive evidence-based interventions targeting Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) or hepatitis11. Among the minority of community-based adolescent substance abuse treatment programs that do provide some prevention programming, the types of programs they offer are often “homegrown” and of unknown effectiveness rather than interventions that have been validated empirically12.

Significant barriers to the widespread adoption of science-based HIV and infectious disease prevention interventions exist. Evidence-based prevention interventions are expensive to implement and strain available resources, given the limited staffing and high caseloads at the average treatment program. Delivering evidence-based HIV prevention interventions requires considerable staff training and ongoing supervision. Even if staff in community treatment programs initiate evidence-based HIV prevention interventions, it may be difficult to ensure their fidelity5, 13. Further, many program staff may feel uncomfortable or unprepared to discuss behavior that may place youth at risk for HIV and other infectious diseases and to customize prevention efforts based on the needs of a given adolescent13. Additionally, even though many youth report struggling with their lack of knowledge about sexual health14 and despite the fact they are more willing to discuss health after sexual experience (3.8 OR for females 1.9 OR for males compared to those without sexual experience15), they are often reluctant to discuss their health behavior with clinicians or educators due to the personal and sensitive nature of the topic. These factors make the translation of empirically supported interventions to real-world settings difficult.

There is a need to employ innovative approaches to address these challenges and enable rapid and widespread diffusion of evidence-based HIV and infectious disease prevention interventions to adolescents with substance use disorders in community-based settings. Technology-mediated prevention interventions, such as those delivered via the Internet, have the potential to address these challenges by enabling complex interventions to be delivered with high fidelity and at low cost, without increasing demands on staff time or training needs14. Also, computerized programs may be less threatening to patients and provide greater anonymity than face-to-face modalities, which may be of particular relevance when the sensitive issues of sexual behavior and drug-taking are addressed. Such programs may also appeal to individuals who normally resist other forms of learning. Further, those who are currently adolescents and have grown up in an age of exponentially-progressing technology often have high technological literacy and are generally receptive to new devices and applications15. Computer-based interventions, when delivered via the web, can also be quickly and centrally updated to accommodate new information as it becomes available. Moreover, they are readily customizable, capable of delivering interventions that are tailored to a given individual’s risk factors, knowledge, and skills training needs, and flexible, allowing users to access the intervention at convenient times16. Thus, web-based tools offer strong potential for widespread dissemination of evidence-based HIV and infectious disease prevention.

A web-delivered infectious disease prevention intervention offered as part of substance abuse treatment may be particularly attractive to adolescents. Prior work has shown that existing models of care offered to youth in substance abuse treatment may have limited acceptability. For example, among the most significant barriers to participation in substance abuse treatment by adolescents are reports of dislike for their therapist, feeling uncomfortable talking about personal problems with another person, and feeling like counselor-provided interventions were not helpful17. Computer-based interventions may thus be appealing to youth because of the anonymous and non-judgmental environment they afford. Indeed, one study found that youth indicated they would prefer Internet-delivered interventions as part of substance abuse treatment instead of more traditional interventions18. Additionally, many youth report that they find interactive computer learning environments to be preferable to traditional learning environments in that computer-based learning provides the opportunity for active and independent problem solving and individualized feedback19. These technological solutions are highly scalable and may be cost-effective, making it possible to deliver effective interventions to a much larger portion of those who are in need.

The Therapeutic Education System (TES) is an interactive, customizable, web-based program, which (as part of a larger suite of tools for persons with substance use disorders) includes content and functionality focused on the prevention of HIV, STIs and hepatitis. TES has been used for both substance abuse treatment20–22 and HIV prevention23. TES incorporates effective components of both prevention science and educational technologies that promote mastery and long-term retention of key information and skills, and is based in the community reinforcement approach to behavior therapy20. The version of TES used in this study contains 26 total modules. Modules provide information about HIV, hepatitis and STIs, teach how alcohol and other substance use may increase one’s risk for contracting various infections/diseases, provide information on risk reduction (e.g., correct condom use, identification and management of triggers for risky sexual behavior or drug use), and teach relevant skills (e.g., decision-making skills, negotiation skills). Additionally, several modules are geared specifically for individuals who may be infected with hepatitis or with HIV.

A previous randomized, controlled trial demonstrated the efficacy of this HIV, hepatitis and STI prevention program when offered to adolescents in outpatient substance abuse treatment as an adjunct to a traditional HIV prevention intervention delivered by a trained HIV educator in a small group setting. Specifically, the combination of the web-based and traditionally-delivered prevention interventions promoted significantly increased HIV/disease prevention knowledge and intentions to engage in safer sex practices, and was also perceived as more useful, relative to an educator-delivered intervention alone23. The present study evaluated the comparative effectiveness of this web-based intervention vs. a traditional, educator-delivered intervention when offered to youth in outpatient, community-based substance abuse treatment. To our knowledge, this study is the first randomized clinical trial to directly compare a web-based HIV prevention intervention to traditionally delivered prevention in community-based adolescent substance abuse treatment. Such a comparison is particularly important, given that so few adolescent substance abuse treatment programs have the capacity or resources to offer traditional, evidence-based infectious disease prevention interventions to youth.

Methods

New patients (ages 12–18 years) entering outpatient adolescent substance abuse treatment at three collaborating sites within the same treatment system in New York City (located in Brooklyn, the Bronx and Queens) were eligible to participate in this randomized, controlled, comparative effectiveness trial. Participants had to be within the first 30 days of substance abuse treatment and must not have been exposed to a formal HIV prevention intervention during their current treatment episode. Adolescents were excluded if they planned to move out of the area within the period of evaluation in this trial, had insufficient ability to understand and provide informed consent/assent to participate, or lacked sufficient fluency in English to participate in the consent process, the interventions or assessments.

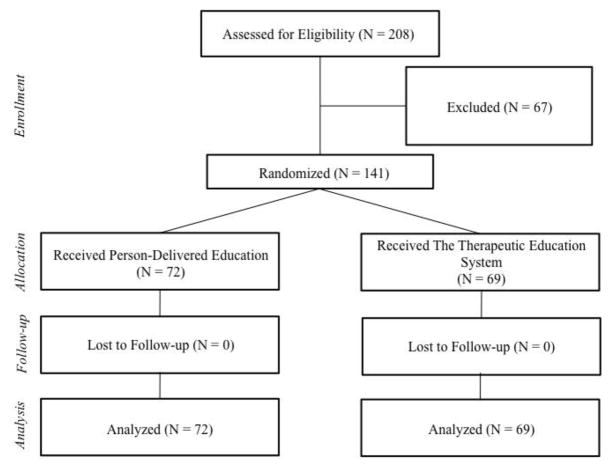

As reflected in the CONSORT diagram in Figure 1, 208 individuals were screened for study eligibility and 141 of these individuals were randomly assigned to one of two study conditions in an intent-to-treat design (N = 67 excluded): (1) a small group intervention delivered by an educator trained as a specialist in HIV, hepatitis and STI prevention (N = 72) or (2) an interactive, web-delivered intervention focused on HIV, hepatitis and STI prevention (N = 69). Three characteristics were used to stratify patients to study conditions: (1) study site; (2) gender (as differential HIV risk behavior has been observed across genders24); and (3) whether a participant did/did not meet dependence criteria (vs. abuse criteria) on any substance (except nicotine) as measured via the DSM-IV checklist (as level of severity of substance use has been shown to influence risk behavior among adolescents25). Randomization occurred immediately after an individual was determined to be eligible for the trial and appropriate informed consent/assent procedures and baseline assessments had been completed.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram of the TES Randomized Controlled Trial

Participants assigned to TES condition were required to complete all modules assigned to them in order to be considered to have completed the intervention. If a participant indicated in their initial computerized risk behavior assessment in TES that they were HIV or HCV positive, they would be assigned an additional set of optional modules (this did not apply to any participants in the current study). All participants who were assigned to the TES condition and finished the intervention completed the same set of core modules. Each participant had to go through each module once (i.e., read the text or listen to the voiceover and then correctly complete the questions at the end of each module). Module length varied by each participant’s reading speed. The time for completing each module ranged between 10 – 30 minutes.

Educator-Delivered Intervention Condition

Participants who were randomly assigned to the educator-delivered intervention condition were asked to participate in two meetings, each of which lasted approximately one hour. A trained HIV and infectious disease prevention specialist experienced in working with youth conducted these sessions. To best reflect traditional approaches to delivering HIV prevention to adolescents in substance abuse treatment, these sessions were typically conducted in small groups of two to four participants but were sometimes offered individually. In these sessions, the prevention specialist provided (using bullet-pointed visual aids): descriptions of HIV/AIDS, hepatitis A, B and C, and STIs; basic transmission dynamics for each; strategies to reduce the risk of becoming infected with these diseases from sexual activity (including a demonstration, on a penis model, of how to correctly use a condom); strategies to reduce drug-related risk; and information on getting tested for HIV, hepatitis and STIs. The content of these sessions was based on the Principles of HIV Prevention in Drug Using Populations published by NIDA26. Additionally, as part of these sessions, participants viewed the 20-minute youth-centered HIV prevention video, “HIV: Hey, It’s Viral!”27.

Web-Delivered Intervention Condition

Participants who were randomly assigned to this study condition were offered access to a self-directed, interactive web-based HIV, hepatitis, and STI prevention program instead of the educator-delivered prevention intervention. The web-based intervention evaluated in this study is part of TES, and is composed of 26 modules (described above and detailed in Table 1), 19 of which address important drug- and sex-related factors that may place youth involved in substance use at risk for HIV, STIs and/or hepatitis, and 7 of which are geared towards youth living with HIV or hepatitis C and address skills for coping with the disease, managing stigma, disclosing one’s serostatus, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. The system also includes a customization program that was used to tailor the intervention to meet the individual prevention needs of each adolescent. In this automated customization scheme, each user completes a computerized risk behavior assessment and then receives a tailored, ordered selection of TES modules to complete. The program uses informational technologies to ensure mastery of content (fluency) via individually paced presentation of content and testing to check for mastery of the material. Participants were asked to complete their customized plan in 60-minute sessions using a dedicated computer at their treatment program. Participants completed the web-based intervention in an average of about three sessions (M = 3.02, SD = 1.36).

Table 1.

Module Topics in the Therapeutic Education System.

| Module Topics |

|---|

|

We assessed the comparative effectiveness of these interventions by examining changes from pre- to post-intervention in accurate HIV/disease prevention knowledge, intentions to engage in safer sex, self-efficacy to use condoms and sex-related HIV risk behavior. Additionally, we examined the extent to which the interventions impacted relevant skills acquisition (i.e., condom use skills) and participants’ willingness to receive risk reduction materials (e.g., condoms). Participants were provided with modest compensation, in the form of $40 gift cards redeemable at local stores, for completing scheduled assessments. The National Development and Research Institutes’ (NDRI) Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Measures

At baseline, all participants were asked to provide key demographic information (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, age), as well as information about the type and extent of any previous HIV, STI and hepatitis C prevention training they had received prior to their participation in the present study.

Within two weeks of completing their assigned intervention, participants completed a post-intervention assessment. The following outcome measures were administered at both baseline and post-intervention time points: the HIV, Hepatitis and STI Knowledge Test; the Behavioral Intentions Scale (BIS); the sexual activity scale of the Risk Behavior Survey (RBS); a measure of Condom Use Skills; the Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale (CUSES); and questions on participant acceptance of risk reduction materials.

The HIV, Hepatitis and STI Knowledge Test28 is a 25-item, true-false test assessing participants’ knowledge of high-risk sexual behaviors and drug practices, risk-reduction steps, and misconceptions regarding HIV/AIDS, hepatitis and STIs. The 7-item BIS29 uses a 6-point Likert scale anchored by “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree” to assess participants’ intentions to take future action to reduce their sex-related HIV risk behavior. The sexual activity component of the RBS30 assesses number and gender of sex partners, frequency of oral, vaginal and anal sex and use of condoms or other barriers (e.g., dental dams) during the past 7 days. Condom Use Skills29 were evaluated by asking participants to enact nine steps involved in using a condom (demonstrated on a penis model). The 28-item CUSES30 uses a 5-point Likert scale anchored by “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree” to assess HIV-specific constructs predictive of risk behavior including skills for negotiating safer sex, condom use self-efficacy, and attitudes toward condoms.

At the post-intervention time point only, participants completed an intervention Feedback Survey consisting of 6 visual analog scale items (with values ranging 0–100) asking participants to rate how 1) interesting, 2) easy to understand, and 3) useful their assigned prevention intervention was, and the extent to which the intervention 4) promoted new learning, 5) provided new skills development, and 6) helped them change their behavior. Scale items were anchored with binary phrases ranging from, for example, “not interesting” to “very interesting”

Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used for all pre-post analyses because of this analytical approach’s ability to accommodate longitudinal, correlated, and incomplete data, and to model categorical and continuous outcome variables within the same framework. Like mixed modeling, GEE makes adjustments to estimates based on clustering, accounting for nested data. A Welches t-test was used to analyze non-longitudinal patient feedback data instead of a traditional t-test in order to accommodate the unequal variances across conditions.

Findings

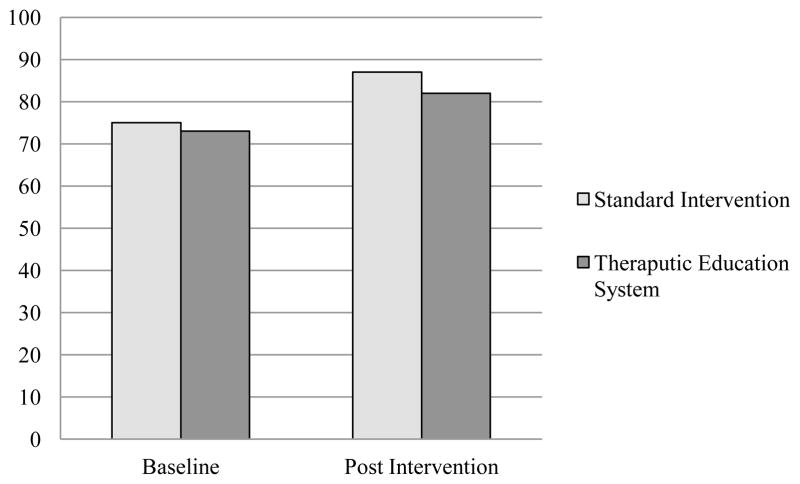

Participants’ baseline sociodemographic characteristics are reported in Table 2. Participants in the two study conditions did not differ significantly on any characteristics measured at baseline, including age, gender, last grade completed, race, ethnicity, history of prior substance abuse treatment and prior receipt of education regarding HIV, hepatitis C or STIs. Pre-post comparisons with group interactions are reported in Table 3 along with outcome descriptives in Table 4. Participants in both conditions achieved comparable increases in accurate knowledge about HIV and hepatitis, as measured via the HIV and Hepatitis Knowledge Test. Intervention groups did not differ in the size of this increase (see Figure 2). An examination of individual items on this assessment indicated that eleven items largely contributed to this pre-post time effect. These items on which participants showed significant increases in accurate knowledge centered on themes involving misconceptions about cleaning needles, preventive behaviors, hepatitis-specific misconceptions, and HIV transmission misconceptions (e.g. “A person cannot get HIV from pre-ejaculatory fluids”, “Cleaning needles with water will kill HIV and hepatitis.”).

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics by Study Condition.

| Variable | Educator-delivered HIV Prevention (N = 72) |

Web-based HIV Prevention (TES) (N = 69) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| % Male | 76.39 | 78.26 |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| % Black | 45.83 | 44.93 |

| % White | 8.33 | 7.25 |

| % Multiple Race | 12.5 | 17.39 |

| % Other | 33.33 | 30.43 |

|

| ||

| Age (M/SD) | 15.76 (1.08) | 15.85 (1.10) |

| Last Grade Completed | 8.79 (1.01) | 8.91 (1.07) |

|

| ||

| Ethnicity | ||

| % Hispanic | 50.00 | 52.17 |

|

| ||

| Treatment History | ||

| % Received Previous Substance Abuse Treatment or Counseling | 64.79 | 71.01 |

|

| ||

| Received Previous HIV, Hepatitis and STI Education | ||

| % HIV Education | 78.87 | 82.35 |

| % Hepatitis Education | 25.35 | 14.71 |

| % STI Education | 60.56 | 64.71 |

Table 3.

Pre-post comparison results across Therapeutic Education System (TES) and standard conditions.

| Measure | χ2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| HIV & Hepatitis Knowledge Test | ||

| Pre-Post | 81.72 | p < .001 |

| Condition by Time | 1.54 | p > .05 |

|

| ||

| Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale | ||

| Pre-Post | 4.01 | p < .05 |

| Condition by Time | 0.03 | p < .05 |

|

| ||

| Condom Use Skills Checklist | ||

| Pre-Post | 34.56 | p < .0001 |

| Condition by Time | 0.21 | p > .05 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (Overall) |

||

| Pre-Post | 4.02 | p < .05 |

| Condition by Time | 0.07 | p > .05 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (# of women received oral sex from, both genders) |

||

| Pre-Post | 12.17 | p < .01 |

| Condition by Time | 0.09 | p > .05 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (# of women performed oral sex on, both genders) |

||

| Pre-Post | 14.10 | p < .01 |

| Condition by Time | 4.94 | p < .05 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (# of men received oral sex from, just women) |

||

| Pre-Post | 3.89 | p = .05 |

| Condition by Time | 7.29 | p < .01 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (# of women vaginal sex, just males) |

||

| Pre-Post | 11.75 | p < .01 |

| Condition by Time | 1.63 | p > .05 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (# of men vaginal sex, just females) |

||

| Pre-Post | 5.39 | p < .05 |

| Condition by Time | 0.78 | p > .05 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (Unprotected sex) |

||

| Pre-Post | 0.25 | p > .05 |

| Condition by Time | 0.71 | p > .05 |

|

| ||

| Behavioral Intentions Scale | ||

| Pre-Post | 0.71 | p > .05 |

| Condition by Time | 0.41 | p > .05 |

Table 4.

Outcome variable descriptive statistics split by intervention group (TES and Standard) for pre- and post-test.

| Measure | Standard M/SD Pre N = 72 Post N = 30 |

TES M/SD Pre N = 69 Post N =44 |

|---|---|---|

| HIV & Hepatitis Knowledge Test | ||

| Pre-test | 0.75/0.09 | 0.73/0.11 |

| Post-test | 0.87/0.08 | 0.82/0.11 |

|

| ||

| Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale | ||

| Pre-test | 3.26/0.57 | 3.35/0.51 |

| Post-test | 3.38/0.51 | 3.44/0.44 |

|

| ||

| Condom Use Skills Checklist | ||

| Pre-test | 6.09/1.16 | 6.08/1.06 |

| Post-test | 6.74/0.90 | 6.84/1.15 |

|

| ||

| Risk Behavior Survey (Overall) | ||

| Pre-test | 1.20/1.41 | 1.36/1.79 |

| Post-test | 0.81/0.98 | 1.07/1.08 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (# of women received oral sex from, both genders) |

||

| Pre-test | 1.58/2.07 | 1.53/1.80 |

| Post-test | 0.82/0.75 | 0.63/0.72 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (# of women performed oral sex on, both genders) |

||

| Pre-test | 0.48/0.78 | 0.18/0.61 |

| Post-test | 0.00/0.00 | 0.06/0.25 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (# of men received oral sex from, just women) |

||

| Pre-test | 2.71/1.60 | 2.83/1.47 |

| Post-test | 3.00/0.00 | 1.00/0.00 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (# of women vaginal sex, just males) |

||

| Pre-test | 1.83/1.56 | 2.03/2.05 |

| Post-test | 0.82/0.60 | 1.56/1.03 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (# of men vaginal sex, just females) |

||

| Pre-test | 1.33/1.00 | 1.10/0.32 |

| Post-test | 2.00/0.00 | 1.40/0.89 |

|

| ||

|

Risk Behavior Survey (Unprotected sex) |

||

| Pre-test | 4.31/10.16 | 2.33/5.44 |

| Post-test | 2.25/4.95 | 2.76/6.46 |

|

| ||

| Behavioral Intentions Scale | ||

| Pre-test | 4.82/1.04 | 5.10/0.93 |

| Post-test | 4.96/0.91 | 5.12/0.75 |

Figure 2.

Comparison of Percentage of Correct Answers on the HIV and Hepatitis Knowledge Measure Pre- and Post-Intervention

Participants in both conditions also achieved comparable increases in condom use self-efficacy, and this increase did not differ across groups. Six items on this measure largely contributed to this observed effect and centered on themes of increased confidence in condom application, willingness to use condoms (e.g. to carry them and to use one in the heat of passion), and ability to discuss condom use with sex partners.

A similar pattern was observed on the Condom Use Skills Checklist. Participants in both conditions achieved comparable increases in condom use skills, and this increase was not significantly different between groups. Increases in condom use skills were largely observed on items that covered condom selection (e.g. checking for damage and expiration date) and proper procedures for condom removal.

Results from the Risk Behavior Survey indicated that both groups reported reductions in the number of past-month sex partners, but not in the frequency with which they engaged in unprotected sexual activity, after their prevention intervention as compared to baseline levels. Considering all types of sex acts together (i.e., oral, vaginal and anal), both groups demonstrated significant reductions in number of past month sex partners, and there were no differences between conditions. More specifically, participants in both study conditions reported significant reductions in the number of women from whom they received oral sex in the past month, with no differences across conditions. Participants in both study conditions also reported reductions in the number of women on whom they performed oral sex in the past month, and this reduction was observed to a greater extent in the group that received the web-based intervention. Female participants in both study conditions similarly reported reductions in the number of men from whom they received oral sex in the past month, although this reduction was observed to a greater extent in the group that received the educator-delivered intervention.

Males in both study conditions reported comparable reductions in the number of women with whom they had vaginal sex in the past month, and the groups did not differ significantly on this measure. This same trend was observed among females, such that women in both study conditions reported comparable reductions in the number of males with whom they had vaginal sex in the past month. Again, these decreases did not vary significantly by group. Rates of unprotected sex were somewhat modest at baseline with 33% of the sample reporting any instance of unprotected vaginal sex in the past month. Rates of unprotected sex did not change over time, or differ between groups.

No changes were observed on the Behavioral Intentions Scale over time or between groups.

Finally, participant feedback was compared across the intervention conditions (see Table 5). Participants in both conditions found the interventions to be equally interesting and useful. Both groups reported that they learned a similar amount of new information and a comparable level of new skills. Both groups reported that the interventions helped them change their behavior to a similar degree. However, those in the TES condition reported that the materials in their intervention were much easier to understand (d = -.70).

Table 5.

Participant feedback on intervention content across conditions.

| Measure | M | SEM | t-value | df | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interesting | 1.50 | 74 | p > .05 | ||

| Standard | 73.70 | 3.79 | |||

| Therapeutic Education System | 65.41 | 3.71 | |||

|

| |||||

| Useful | 1.21 | 74 | p > .05 | ||

| Standard | 86.57 | 2.86 | |||

| Therapeutic Education System | 81.87 | 2.53 | |||

|

| |||||

| New Information Learned | 74 | −0.35 | p > .05 | ||

| Standard | 7.70 | 4.35 | |||

| Therapeutic Education System | 72.33 | 2.67 | |||

|

| |||||

| New Skills Learned | 74 | −0.26 | p > .05 | ||

| Standard | 64.73 | 4.15 | |||

| Therapeutic Education System | 66.11 | 3.23 | |||

|

| |||||

| Helped Change Behavior | 73 | 0.50 | p > .05 | ||

| Standard | 64.52 | 5.65 | |||

| Therapeutic Education System | 61.11 | 4.02 | |||

|

| |||||

| Ease of Understanding | 71.19 | −2.95 | p < .01 | ||

| Standard | 10.02 | 2.92 | |||

| Therapeutic Education System | 22.77 | 4.52 | |||

Discussion

This study is the first randomized trial to compare a traditional person-delivered HIV prevention intervention to a technology-delivered prevention intervention among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Overall, results indicate that participants in both intervention conditions achieved gains post-intervention (relative to baseline), demonstrating improvements in sexually transmitted infection knowledge and related skills, as well as reductions in behaviors that place youth at risk for contracting HIV and related infectious diseases. The decrease in these behaviors did not vary across condition. The web-based TES and person-delivered interventions were equally effective, and did not differ in any meaningful way in their ability to impact risk- related knowledge, skills and behavior.

Additionally, although participants did not find either condition more interesting, useful, capable of providing new information or teaching new skills, materials in the TES condition were reported as being much easier to understand. Although this finding needs to be explored in greater detail, the content presented in the TES condition could be easier to understand because it is offered at a pace determined entirely by the participant. This helps to address language barriers and differences in reading ability. If a particular bit of information was unclear, TES users could either linger on that content or revisit it until sufficient understanding was achieved. In contrast - questions, although typically encouraged in educational settings, can be difficult to ask in group contexts, especially considering the sensitive nature of these topics and the social awareness of adolescents.

The finding that TES is just as effective as a traditional, person-delivered intervention is highly promising and underscores the utility of a web-based solution to address the gap between the need for prevention services in substance abuse treatment programs and the currently limited availability of such services. As reviewed above, among the minority of programs that have prevention services, few prevention programs are delivered by trained specialists in accordance with evidence-based practice. A high-fidelity technological solution reduces the demands for training staff and allows treatment programs to offer the same effective intervention to any number of patients. Previous work has shown that TES is an effective adjunct to person-delivered disease prevention. This study builds on that research by demonstrating that technology-based prevention programming can be valuable as a stand-alone intervention. Such approaches could stand in for provider-delivered care in resource poor environments, or allow program staff to focus their efforts elsewhere.

This study was conducted at three urban sites within the same metropolitan area (i.e., the outer boroughs of New York City). Recruitment from these sites was a strength of the project, as it enabled a sample of largely minority substance-using youth from an area that has been, and continues to be, a major hub of HIV transmission. Although understanding the utility of a web-based prevention intervention in this vulnerable population is critical, the demographic, geographic and cultural factors of this particular area may potentially limit the generalizability of these findings. The outer boroughs of New York City, which are among the most densely populated and diverse areas of the United States, present different challenges in comparison to other treatment settings, especially those found in rural locales. Understanding the utility of the web-based intervention in diverse samples of youth is an important consideration for future research.

Contamination is another potential limitation. Youth within these treatment settings had frequent access to one another and it is possible that they discussed the content of their interventions across conditions. However, due to the nature of the topics contained within the intervention, it is unlikely that these issues were discussed at all, especially considering the willingness of youth to discuss these issues with peers that they are not particularly close to.

The surveys that were used to collect data relied on retroactive self-report. This could have biased the results for a few reasons. First, the retroactive nature of the questionnaires is vulnerable to recall errors when reporting past behavior. Further, evaluation of any stigmatized behaviors can be biased by social desirability.

The type of treatment center itself has implications for generalizability. This study drew participants from outpatient substance abuse treatment programs – a setting in which patients often present with a history of HIV risk behavior. Future research may also investigate the effectiveness of the web-based prevention program as a standalone treatment in other care settings - including inpatient treatment centers, mental health specialty treatment settings, primary care, harm reduction services (e.g. syringe exchange programs), hospitals (both non-emergency and emergency departments), schools and direct-to-consumer online (e.g., via social media sites). As reviewed above, one of the main benefits of TES, and technological health care solutions at large, is the scalability of these tools. The highest level of this scale would be large-scale web deployment for in-home consumption. Given the ubiquity of the use of social media and other online resources among youth32, widespread deployment of technology-based therapeutic tools in this manner offers great promise to have a marked public health impact.

Evidence-based interventions, including disease prevention interventions, are not routinely integrated in substance abuse treatment programs because of financial constraints or inadequate provider training. Technology is increasingly being harnessed as a low-cost option for teaching behavioral skills to substance users, thereby broadening their availability. This research constitutes the first randomized clinical trial that directly compares a traditional prevention program to a more scalable and potentially more cost-effective technology-based intervention. Such innovations can accelerate the delivery of science-based, HIV, STI, and hepatitis prevention with fidelity to youth in community-based substance abuse treatment and may promote the rapid adoption of effective prevention interventions. TES provides a comprehensive, science-based, prevention intervention, targeting HIV, hepatitis and STIs, from an automated web-based platform with a high potential for dissemination. This web-based tool, and similar technology-based interventions, if found effective and cost-effective, could substantially advance the substance abuse treatment system by improving the availability and quality of HIV prevention interventions delivered to individuals in a variety of treatment settings. Technological interventions can relieve the demands placed on overly burdened care providers, both at the level of the employee and the organization, and can improve the value and availability of behavioral health care to consumers.

Highlights.

A randomized, controlled effectiveness trial with adolescents in treatment.

We compare HIV, STI and hepatitis prevention intervention methods.

Web-based interventions are as effective as those delivered by a professional.

This technology can be tailored to any population.

Effective low cost behavioral health technology can increase quality of care.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse at the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant #s RC1DA028415 and P30DA029926 PI: Lisa A. Marsch) and is a registered clinical trial (registration NCT01142882). Elaine T. Dillingham is no longer affiliated with National Development and Research Institutes, Inc. In addition to her academic affiliation, Dr. Marsch is affiliated with HealthSim, LLC, the health-promotion software development organization that developed the web-based Therapeutic Education System referenced in this manuscript. Dr. Marsch has worked extensively with her institutions to manage any potential conflict of interest. All research data collection, data management, and statistical analyses were conducted by individuals with no affiliation to HealthSim, LLC.

Footnotes

Lisa Marsch wrote the grant application and secured NIH research funding for this study and served as Principal Investigator on this project. She contributed to the study design, data collection, data interpretation, literature search and manuscript preparation. Honoria Guarino served as Project Director on this project and contributed to the study design, data collection, data interpretation, literature search and manuscript preparation. Cassandra Syckes and Elaine Dillingham contributed to data collection. Michael Grabinski developed and oversaw the implementation of the web-based intervention used in this trial and contributed to data collection and analysis (from the computerized intervention). Haiyi Xie contributed to data analysis and data interpretation. Finally, Benjamin Crosier contributed to the literature search, manuscript writing, creation of the figures and tables, and interpretation of data.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Benton T, Ifeagwu J. HIV in adolescents: What we know and need to know. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2008;10:109–115. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Health for the World’s Adolescent’s. 2014 Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112750/1/WHO_FWC_MCA_14.05_eng.pdf?ua=1.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 U.S. dependent areas—2011. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report. 2013;18(5) [Google Scholar]

- 4.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. HIV Surveillance Mid-Year Report, 2013. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jane Rotheram-Borus Mary, Katherine Desmond, Scott Comulada W, Mayfield Arnold Elizabeth, Mallory Johnson, Mallory Johnson. Reducing risky sexual behavior and substance use among currently and formerly homeless adults living with HIV. American journal of public health. 2009;99(6):1100–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.121186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D’Angelo L, DiClemente RJ. Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection in Adolescents. In: DiClemente RJ, Hansen W, Ponton L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Risk Behavior. New York, NY: Plenum Publishing Cooperation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auerbach JD, Kandathil SM. Overview of effective and promising interventions to prevent HIV infection. World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 2006;938:43–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerressu N, Stephenson JM. Sexual behavior in young people. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2008;21:37–41. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f3d9bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grossman C, Hadley W, Brown LK, Houck CD, Peters A, Tolou-Shams M, et al. Adolescent sexual risk: Factors predicting condom use across the stages of change. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:913–922. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9396-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Committee on Pediatric AIDS. Reducing the Risk of HIV Infection Associated With Illicit Drug Use. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):566–571. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marsch LA, Grabinski MJ, Bickel WK, et al. Computer-Assisted HIV Prevention for Youth With Substance Use Disorders. Substance use & misuse. 2011;46(1):46–56. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins C, Harshbarger C, Sawyer R, Hamdallah M. The diffusion of effective behavioral interventions project: Development, implementation, and lessons learned. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(4) Suppl A:520. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingram BL, Flannery D, Elkavich A, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Common processes in evidence-based adolescent HIV prevention programs. AIDS Behavior. 2008;12:374–383. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9369-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrew G, Patel V, Ramakrishna J. What to integrate in adolescent health services. Reproductive Health Matters. 2003;11:120–129. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burstein GR, Lowry R, Klein JD, Santelli JS. Missed opportunities for sexually transmitted diseases, human immunodeficiency virus, and pregnancy prevention services during adolescent health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 1):996–1001. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.5.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Czaja SJ, Sharit J. Age Differences in Attitudes Toward Computers. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53B(5):P329–P340. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53B.5.P329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bickel WK, Marsch LA. A future for drug abuse prevention and treatment in the 21st century: Applications of computer-based information technologies. In: Henningfield J, Santora PB, Bickel WK, editors. Addiction treatment: Science and policy for the 21st century. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press; 2007. pp. 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marsch L. Leveraging Technology to Enhance Addiction Treatment and Recovery. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2012;31:313–320. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2012.694606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mensinger JL, Diamond GS, Kaminer Y, Wintersteen MB. Adolescent and therapist perception of barriers to outpatient substance abuse treatment. The American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:16–25. doi: 10.1080/10550490601003631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chambers M, Connor SL, McElhinney S. Substance use and young people: The potential of technology. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2005;12:179–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roker D, Coleman J. Education and advice about illegal drugs: What do young people want? Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy. 1997;4:53–64. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bickel WK, Marsch LA, Buchhalter AR, Badger GJ. Computerized behavior therapy for opioid-dependent outpatients: a randomized controlled trial. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;16(2):132–143. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.2.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell ANC, Nunes EV, Matthews AG, Stitzer M, Miele GM, Polsky D, Ghitza UE. Internet-Delivered Treatment for Substance Abuse: A Multisite Randomized Controlled Trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13081055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsch LA, Guarino H, Acosta M, Aponte-Melendez Y, Cleland C, Grabinski M, Edwards J. Web-based behavioral treatment for substance use disorders as a partial replacement of standard methadone maintenance treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014;46(1):43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marsch LA, Grabinski MJ, Bickel WK, Desrosiers A, Guarino H, Muehlbach B, Acosta M. Computer-assisted HIV prevention for youth with substance use disorders. Substance Use & Misuse. 2011;46(1):46–56. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman PA, Zimmerman MA. Gender differences in HIV-related sexual risk behavior among urban African American youth: a multivariate approach. AIDS Education and Prevention: Official Publication of the International Society for AIDS Education. 2000;12(4):308–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leigh BC, Stall R. Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV. Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. The American Psychologist. 1993;48(10):1035–1045. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.10.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of HIV Prevention in Drug Using Populations. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beyondmedia Education. HIV: Hey, It’s Viral. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marsch LA, Bickel WK. The efficacy of computer-based HIV/AIDS education for injection drug users. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004;28:316–27. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malow RM, Dévieux JG, Jennings T, Lucenko BA, Kalichman SC. Substance-abusing adolescents at varying levels of HIV risk: Psychosocial characteristics, drug use, and sexual behavior. 2001. Journal of Substance Abuse. 13:103–117. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Institute on Drug Abuse. Risk Behavior Survey. Developed by National Institute on Drug Abuse, Community Research Branch. 1993 Available online at: http://ctndatashare.org/content/risk-behavior-survey.

- 33.Brafford LJ, Beck KH. Development and validation of a condom use self-efficacy scale for college students. Journal of American College Health. 1991;39(5):219–25. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1991.9936238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pew Research. Internet Project: Teens and Technology. 2013 http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/03/13/teens-and-technology-2013/