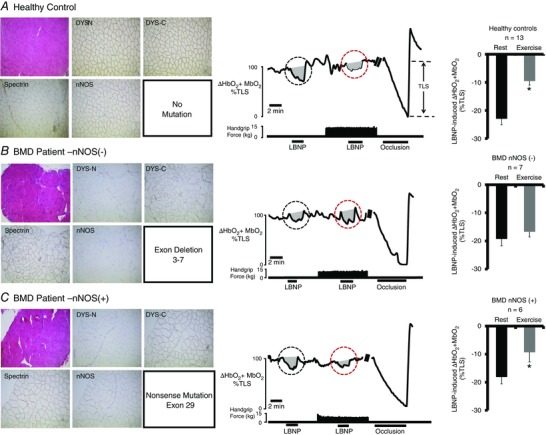

Figure 1. BMD mutations that interrupt sarcolemmal anchoring of nNOS impair functional sympatholysis .

Left: representative immunohistochemistry from muscle biopsies from a healthy control subject (A) and two BMD patients (B and C). Muscle biopsy sections stained with haematoxylin and eosin (upper left) from the two BMD patients show typical dystrophic hallmarks, including variation in muscle fibre size, internal nuclei, fibrosis and an increase in fat tissue. Staining for dystrophin C‐terminus (DYS‐C) is present in both BMD patients, although no staining for dystrophin N‐terminus (DYS‐N) is present (evidence for truncated dystrophin). Sarcolemmal nNOS staining is absent in (B) but present in (C). Middle: representative tracing from a healthy control subject (A), a BMD patient lacking sarcolemmal nNOS (B, P2) and a BMD patient with nNOS retained at the sarcolemma (C, P11). A black circle highlights the LBNP‐induced change in forearm muscle oxygenation at rest, whereas a red circle highlights the LBNP‐induced change in forearm muscle oxygenation during exercise. Note that, in healthy controls, the decrease in forearm muscle oxygenation is greatly attenuated (termed functional sympatholysis). At the end of each experiment, an arm cuff was inflated to suprasystolic pressure to occlude the forearm circulation, producing a maximal decrease in forearm muscle oxygenation to calculate the TLS. Right: summary forearm muscle oxygenation data from 13 healthy subjects (A), seven BMD patients in whom sarcolemmal nNOS was absent (B) and six BMD patients in whom sarcolemmal nNOS was present (C). Data are reported as the mean + SE.