Abstract

In preclinical tumor xenograft experiments, the antitumor activity of the tested agents is often assessed by endpoints such as tumor doubling time, tumor growth delay (TGD), and log10 cell kill (LCK). In tumor xenograft literature, the values of these endpoints are presented without any statistical inference, which ignores the noise in the experimental data. However, using exponential growth models, these endpoints can be quantified by their growth curve parameters, thus allowing parametric inference, such as an interval estimate, to be used to assess the antitumor activity of the treatment.

Keywords: Exponential growth curve, log10 cell kill, Tumor doubling time, Tumor growth delay, Xenografts

1. INTRODUCTION

The assessment of antitumor activity of the tested agents in preclinical tumor xenograft experiments is important for finding promising new compounds for human cancer treatment. Several endpoints may be chosen to characterize the effectiveness of the treatment, such as tumor doubling time, tumor growth delay (TGD), and log10 cell kill (LCK) (Demidenko, 2004, 2010). In tumor xenograft literature, the values of these endpoints are presented without any statistical inference, which ignores the noise in the experimental data (Corbett et al., 2003; Houghton et al., 2007). Recently, Wu and Houghton (2009) developed a bootstrap interval of the LCK to assess the antitumor activity. The proposed interval estimation is purely nonparametric without tumor growth modeling. However, in short-term animal experiments, tumor growth often can be fitted by a growth curve. For example, an untreated tumor growth is usually well approximated by an exponential curve

| (1) |

where V(t) is the tumor volume at time t, V0 is the initial volume, and b is a parameter characterizing the rate of tumor growth. The growth of a treated tumor is more complicated and difficult to model through its entire growth curve. However, the regrowth curve of a treated tumor often follows an exponential curve, too. To quantify the antitumor activity of a treatment based on these endpoints, it is only necessary to model the exponential regrowth curve for the treated tumor.

Tumor growth curve theory is well established, with a long history in biomathematics and biostatistics. One of the pioneer investigations in tumor growth kinetics was made by Skipper et al. (1964), who described the first model of tumor growth kinetics—an exponential growth. The Gompertz growth curve was introduced by Gompertz (1825) and has proven to be well suited to describe the growth of an unperturbed tumor (Lloyd, 1975; Norton, 1988). However, both exponential and Gompertz curves often do not fit the growth curve of the treated tumor. Norton and Simon (1977) and Hanfelt (1991) proposed some generalized Gompertz curves to describe treated tumor growth. Demidenko (2004) and Liang and Sha (2004) applied a biexponential curve to treated tumor growth. Demidenko (2006) proposed a linear-exponential regrowth curve analysis. Liang (2005) proposed a spline growth curve model and applied it to tumor xenograft data analysis. However, these proposed models are only applied to a certain of specific tumor growth curves.

In general, the treated tumor growth curve is difficult to model. Therefore, in our approach, only tumor regrowth is modeled by an exponential curve. The tumor doubling time, TGD, and LCK then can be formulated by curve parameters. Therefore, point estimates and confidence intervals of these endpoints can be derived from the growth curve analysis.

2. TUMOR DOUBLING TIME

A useful measure of tumor growth rate is tumor doubling time tD, which is defined as the time it takes for a tumor to double its starting volume. For an exponential growth curve as in Eq. (1), the doubling time tD starting volume at time t0 is determined by the following equation:

The doubling time tD is then solved as

| (2) |

which is independent of the starting time t0 and inversely proportional to the tumor growth rate b. Therefore, measuring the tumor doubling time is equivalent to measuring the tumor growth rate for an exponential growth curve. Since tumor volumes are measured at certain time points during the study period, the exact tumor doubling time tD of an individual tumor is often not observed. However, one can fit the following linear regression line:

| (3) |

where yj = ln{V(tj)} is the natural logarithm tumor volume at time tj for the jth time point and {ej} are the independent N(0, σ2) variates of measurement errors. The model slope parameter b can be estimated by b̂ with standard error from the well-known regression theorem (Weisberg, 2005). Therefore, the tumor doubling time tD can be estimated by

and its standard error is derived by the delta method,

Since t̂D is the inverse of normal variate b̂, the distribution of t̂D is skewed. To construct the interval estimate, taking a logarithm transformation of the t̂D, the standard error of ln(t̂D) can be derived by the delta method,

Therefore, a 100(1 − α)% confidence interval of tD is given by

| (4) |

where z1−α/2 is the 100(1 − α/2) percentile of the standard normal distribution. An alternative 100(1 − α)% confidence interval of tD can be obtained by constructing the confidence interval of b and taking the inverse of it (Hanfelt, 1997):

| (5) |

where tn−2,1−α/2 is the 100(1 − α/2) percentile of the t-distribution with degrees of freedom of n − 2.

To assess the treatment effect, the ratio doubling times of treated versus untreated may be of interest:

where tD(T), bT and tD(C), bC represent the tumor doubling times and growth rates of the treated and untreated tumors, respectively. The growth rates bT and bC can be estimated by fitting the following regression model:

| (6) |

where yij = ln{V(tij)}, xi takes value of 0 and 1 for i = T and C, respectively, and {eij} are the independent N(0, σ2) variates of measurement errors. By noting the independence between b̂C and b̂T, the interval estimate of γ can be obtained by the delta method and Fieller’s theorem (Fieller, 1954). The standard error of γ̂ = b̂C/b̂T can be derived by the delta method:

where and . Therefore, a 100(1 − α)% delta interval of the ratio γ is given by

| (7) |

Since γ is expressed as a ratio, applying Fieller’s theorem, the Fieller’s interval can be obtained by solving the following equation for γ:

where tdf,1−α/2 is the percentile of the t-distribution with degrees of freedom df = nT + nC − 4. A 100(1 − α/2)% Fieller’s interval is then given by

| (8) |

where

3. LOG10 CELL KILL

The effectiveness of a tested agent is often assessed by the number of cells killed by the treatment. Lloyd (1975) provided a formal definition of log10 cell kill (LCK), which is defined as the negative log10 fraction of tumor cells surviving treatment (F), that is,

| (9) |

The quantification of the LCK for a tumor growth model is based on the following assumptions: (a) Growth of the untreated tumor follows an exponential growth curve, (b) mass (and corresponding volume) of a tumor is directly proportional to the number of malignant cells in the mass, and (c) the treated tumor regrowth curve is the same as that of an untreated control tumor. Under these assumptions, the regrowth curve of the treated tumor is identical to that of the untreated tumor, separated in time by amount τ:

Let t* represent the treatment starting time; then the fraction of the tumor cells surviving after treatment may be formulated as

Therefore, the LCK defined by Eq. (9) is given by

| (10) |

where T–C is the difference in times to the predetermined size between treated and untreated tumors and 3.32 is an approximate value of log2(10). The final expression of Eq. (10) of the LCK has been widely used in the tumor xenograft literatures (Corbett et al., 2003).

To express the LCK by the regrowth curve parameter θ defined next, let yt = ln{V(t)} be the logarithm tumor volume, and suppose the untreated tumor grows according to yt = a + bt and the treated tumor regrows according to yt = a − θ + bt = a + b(t − τ), where θ is the difference of the intercepts between untreated curve, and treated regrowth curve which quantifies the number of cells killed by the treatment. Then θ = bτ, and the LCK of Eq. (10) is expressed as

The parameter θ can be estimated by fitting the following regression model:

| (11) |

where yij = ln{V(tij)}, xi takes a value of 0 and 1 for i = T and C, respectively, and {eij} are the independent N(0, σ2) variates of measurement errors. An estimate of LCK is then given by

| (12) |

and its standard error is

A 100(1 − α)% confidence interval of LCK is given by

| (13) |

4. TUMOR GROWTH DELAY

Tumor response to treatment is also often assessed by TGD, which is defined as the difference in times from initial treatment to the predetermined size between treated and untreated tumors. To make parametric inference for the TGD, two scenarios are next discussed.

Scenario 1: Parallel growth and regrowth curves

To estimate the TGD, using the same notations as given in the previous section, suppose the untreated tumor grows (in logarithmic scale) according to yt = a + bt and the treated tumor regrows according to yt = a − θ + bt = a + b(t − τ). Then the TGD is expressed as (also see Demidenko, 2006, 2010) as

The model parameters b and θ can be estimated by fitting regression model (11). The TGD can be estimated by

The standard error of can be estimated by the delta method:

where , and . Therefore, a 100(1 − α)% delta interval of the TGD is given by

| (14) |

Since the TGD is also expressed in a ratio form, Fieller’s interval can be obtained by solving the following equation for τ:

where df = nT + nC − 3. A 100(1 − α/2)% Fieller’s interval is given by

| (15) |

where

Scenario 2: Nonparallel growth and regrowth curves

The growth rate of a tumor regrowing after treatment is usually slower than that of the untreated controls. Although this may not be universally true, it occurs in most experimental tumors due to the “tumor bed effect” (Begg, 1980). In such nonparallel growth cases, the procedure for determining tumor cell kill is questionable; however, the TGD may still provide useful information (Lloyd, 1975).

Suppose an untreated tumor grows (in logarithmic scale) according to the curve yt = aC bCt and a treated tumor regrows according to the curve yt = aT + bTt and bC ≠ bT. An F-test derived from regression analysis can be used to test the equal slopes of two growth curves. Let c be the prespecified tumor size (in logarithm scale) for the TGD endpoint. Then the TGD is τ = t2 – t1, where t1 and t2 are the solutions of the following equations:

Therefore,

The model parameters aC, bC, aT, and bT can be estimated by fitting regression model (6). The TGD can be estimated by

Let

Using the delta method, the variance of f(â, b̂) is given by

The standard error of can be estimated by

Therefore, a 100 (1 – α)% delta interval of the TGD is given by

| (16) |

5. SIMULATION STUDY

Simulations were carried out to study the 95% coverage probabilities of intervals discussed in previous section under various scenarios. The time points of tumor volume measurement were set up to be n = 7 and 11 weeks (in unit days) starting from day 0, and the standard deviation σ of the measurement error ranges from 0.01 to 0.5. The growth rates were set to be b = 0.1 for single growth curve or parallel growth curves and bC = 0.2 and bT = 0.1 for untreated and treated tumor of nonparallel growth curves, respectively. For each parameter configuration, 5,000 independent Monte Carlo samples were used to ensure that the Monte Carlo error for estimating a 95% coverage probability is about 0.003 = (0.05 × 0.95/5000)1/2. The empirical coverage probability of each interval is the frequency of number of intervals including the true parameter of interest. The simulation results are given in Table 1. Since the inverse interval and Fieller’s intervals are exact, the simulated coverage probabilities, of these intervals are closer to the nominal level of 0.95. All delta intervals have lower coverage probabilities, which indicates that the delta intervals are liberal. However, as the number of measurements increases, the coverage probabilities of the delta intervals are improved.

Table 1.

Empirical coverage probabilities of 95% confidence intervals based on 5,000 Monte Carlo samples

| n | Methoda | Standard deviation (σ)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.5 | ||

| 7 | Delta (4) | 0.888 | 0.887 | 0.889 | 0.890 |

| Inverse (5) | 0.948 | 0.948 | 0.948 | 0.948 | |

| Delta (7) | 0.911 | 0.913 | 0.913 | 0.917 | |

| Fieller (8) | 0.945 | 0.946 | 0.946 | 0.946 | |

| Delta (14) | 0.929 | 0.930 | 0.929 | 0.930 | |

| Fieller (15) | 0.950 | 0.950 | 0.950 | 0.954 | |

| Delta (16) | 0.923 | 0.923 | 0.925 | 0.931 | |

| 11 | Delta (4) | 0.920 | 0.921 | 0.920 | 0.920 |

| Inverse (5) | 0.951 | 0.951 | 0.951 | 0.951 | |

| Delta (7) | 0.936 | 0.937 | 0.938 | 0.937 | |

| Fieller (8) | 0.951 | 0.952 | 0.952 | 0.952 | |

| Delta (14) | 0.936 | 0.935 | 0.936 | 0.937 | |

| Fieller (15) | 0.951 | 0.951 | 0.951 | 0.951 | |

| Delta (16) | 0.937 | 0.937 | 0.937 | 0.938 | |

Where delta (×), inverse (×), or Fieller (×) means the delta, inverse, or Fieller interval given by equation number of (×) in the paper.

6. EXAMPLES

Three data sets were selected from a published Pediatric Preclinical Testing Program (PPTP) study (Houghton et al., 2007). The first data set listed the volumes of an untreated tumor from a Wilms tumor line KT-11 xenograft experiment. The data show that the tumor followed an exponential growth curve (Figure 1). Fitting the linear regression model (3) on the logarithm tumor volume, the rate of growth and its standard error are b̂ = 0.0466 (day−1) and , respectively, with residual standard error σ̂ = 0.037 and model R2 = 0.998. Then the tumor doubling time is t̂D = ln(2)/0.0466 = 14.87 (days), and its standard error is . Therefore, the 95% confidence intervals of tD are [14.26, 15.51] and [14.19, 15.63] for delta method (4) and inverse method (5), respectively.

Figure 1.

Exponential growth curve of an untreated tumor from a Wilms tumor line KT-11 xenograft model.

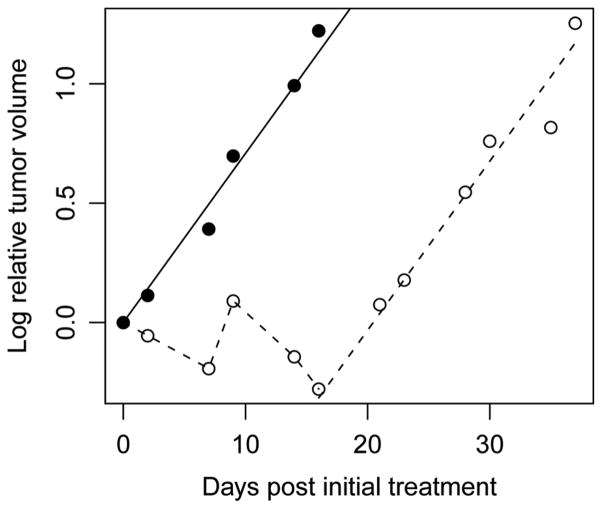

The other two data sets describe the osteosarcoma tumor line OS-2 xenografts. Each data set describes an untreated tumor and a treated tumor. The treated mouse was given cyclophosphamide at 150mg/kg intraperitoneally every 7 days for 6 weeks. Tumor volumes were measured every 2 or 5 days. The growth curves are plotted in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Parallel growth curves for an untreated tumor and a treated tumor from a osterosacoma tumor line OS-2 xenograft model. The dots/solid line and circles/broken line represent the observed log relative tumor volumes and fitted regression line for the untreated tumor and treated tumor, respectively.

Figure 3.

Nonparallel growth curves for an untreated tumor and a treated tumor from a osterosacoma tumor line OS-2 xenograft model. The dots/solid line and circles/broken line represent the observed log relative tumor volumes and fitted regression line for the untreated tumor and treated tumor, respectively.

For the parallel group data (Figure 2), since initial volumes of the two tumors are not equal, relative tumor volume (tumor volume divided by initial volume) was used. Let yt be the logarithm of the relative tumor volume. After fitting the regression model (11), the untreated tumor grows according to yt = b̂t with growth rate (standard error) b̂ = 0.071(0.003) and the treated tumor regrows starting on day 16 according to yt = −θ̂ b̂t with θ̂ = 1.44(0.086) and .

Therefore, the estimate of LCK (standard error) is

The 95% confidence interval of the LCK is [0.57, 0.69], which shows that cyclophosphamide does not have high antitumor activity against the tumor line OS-2 based on the cutoff point of LCK > 0.7 (Corbett et al., 2003). The estimate of TGD (standard error) is

The 95% confidence intervals of the TGD are [18.81, 22.10] and [18.64, 22.40] for delta method (14) and Fieller’s method (15), respectively.

For nonparallel group data (Figure 3), fitting the regression model (6) to the logarithm relative tumor volume data shows that the untreated tumor grows according to yt = âC b̂Ct with âC = 0.224(0.141) and b̂C = 0.103(0.017), and the treated tumor regrows starting at day 16 according to yt = âT b̂Tt with âT = −1.568(0.292) and b̂T = 0.061(0.010). For the presepecified relative tumor size 2, the estimate of TGD is given by , with standard error of 2.2 (day). The 95% confidence interval of the TGD is [27.9, 36.7].

From these examples, we observed that the delta interval is narrower than the Fieller’s interval. The lower coverage probability of the delta interval from simulation study explains its narrow interval compared to the Fieller’s interval.

7. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Using exponential growth and regrowth curve models, tumor doubling time, TGD, and LCK can be expressed by model parameters. Therefore, parametric inference can be made for these endpoints by a simple regression analysis. The confidence intervals obtained using Fieller’s method are exact. Simulation study shows that the interval obtained using delta method is liberal for small sample. Therefore, for small sample data, Fieller’s interval is recommended. Finally, for group data, more comprehensive analysis would involve a mixed model (Demidenko, 2010). If tumor growth follow Gompertz curves, following Lloyd’s derivation (Lloyd, 1975), one can make statistical inference on these endpoints by applying a nonlinear mixed model.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledge two anonymous reviewers and an associate editor for their valuable comments and suggestions that improved the earlier version of this paper. The work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants CA21765 and N01-CM-42216 and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

References

- Begg AC. Analysis of growth delay data: potential pitfalls. British Journal of Cancer. 1980;41(suppl IV):93–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett TH, White K, Polin L, Kushner J, Paluch J, Shih C, Grossman CS. Discovery and preclinical antitumor efficacy evaluations of LY32262 and LY33169. Investigational New Drugs. 2003;21:33–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1022912208877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidenko E. Mixed Model: Theory and Applications. New York: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Demidenko E. The assessment of tumor response to treatment. Applied Statistics. 2006;55:365–377. [Google Scholar]

- Demidenko E. Three endpoints of in vivo tumour radiobiology and their statistical estimation. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2010;86:164–173. doi: 10.3109/09553000903419304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieller EC. Some problems in interval estimation. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society B. 1954;16:175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Gompertz B. On the nature of the function expressive of the law of human mortality, and on a new mode of determining the value of life contingencies. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London. 1825;123:513–585. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanfelt JJ. Statistical approaches to experimental design and data analysis of in vivo studies. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 1997;46:279–302. doi: 10.1023/a:1005946614343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitjan DF. Generalized Norton–Simon models of tumor growth. Statistics in Medicine. 1991;10:1075–1088. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780100708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton PJ, Morton CL, Gorlick R, Kolb EA, Lock R, Reynolds CP, Maris J, Wu J, Liu T, Billups CA, Khan J, Kier ST, Friedman HS, Smith M. The pediatric preclinical testing program: description of models and early testing results. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2007;49:928–940. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H. Modeling antitumor activity in xenograft tumor treatment. Biometrical Journal. 2005;47:1–11. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200310113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Sha NJ. Modeling antitumor activity by using a nonlinear mixed-effects model. Mathematical Biosciences. 2004;189:61–73. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd HH. Estimation of tumor cell kill from Gompertz growth curve. Cancer Chemotherapy Reports. 1975;59:267–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton L. Gompertzian model of human breast cancer growth. Cancer Research. 1988;48:7067–7071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton L, Simon R. The growth curve of an experimental solid tumor following radiotherapy. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1977;58:1735–1741. doi: 10.1093/jnci/58.6.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skipper HE, Schabel FM, Jr, Wilcox WS. Experimental evaluation of potential anti-cancer agents XII: On the criteria and kinetics associated with curability of experimental leukemia. Cancer Chemotherapy Reports. 1964;35:1–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg S. Applied Linear Regression. 3. New York: Wiley; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Houghton PJ. Assessing cytotoxic treatment effects in preclinical tumor xenograft models. Journal of Biopharmaceutical Statistics. 2009;19:755–762. doi: 10.1080/10543400903105158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]