Abstract

Purpose:

We investigated the prognostic utility of visually estimated coronary artery calcification (VECAC) from low dose computed tomography attenuation correction (CTAC) scans obtained during SPECT/CT myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI), and assessed how it compares to coronary artery calcifications (CAC) quantified by calcium score on CTACs (QCAC).

Methods:

From the REFINE SPECT Registry 4,236 patients without prior coronary stenting with SPECT/CT performed at a single center were included (age: 64±12 years, 47% female). VECAC in each coronary artery (left main, left anterior descending, circumflex, and right) were scored separately as 0 (absent), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe), yielding a possible score of 0-12 for each patient (overall VECA grade zero:0, mild: 1-2, moderate: 3-5, severe: >5). CAC scoring of CTACs was performed at the REFINE SPECT core lab with dedicated software. VECAC was correlated with categorized QCAC (zero: 0, mild: 1-99, moderate: 100-399, severe: >400).

Results:

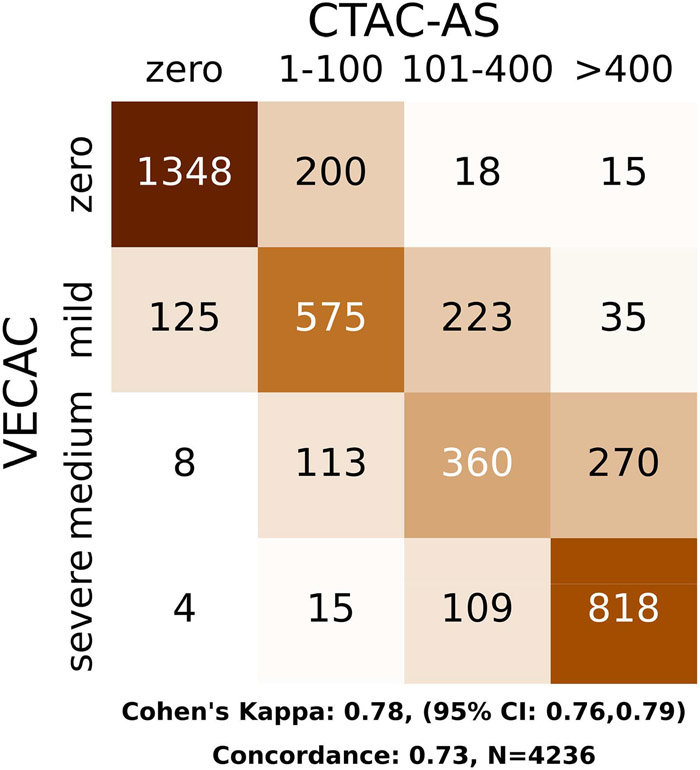

A high degree of correlation was observed between VECAC and QCAC, with 73% of VECACs in the same category as QCAC and 98% within one category. There was substantial agreement between VECAC and QCAC (weighted kappa: 0.78 with 95% confidence interval: 0.76-0.79), p < 0.001). During a median follow-up of 25 months, 372 patients (9%) experienced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). In survival analysis, both VECAC and QCAC were associated with MACE. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for 2-year-MACE was similar for VECAC when compared to QCAC (0.694 versus 0.691, p=0.70).

Conclusion:

Visual assessment of CAC on low-dose CTAC scans provides good estimation of QCAC in patients undergoing SPECT/CT MPI. Visually assessed CAC has similar prognostic value for MACE in comparison to QCAC.

Keywords: coronary calcification, calcium scoring, attenuation CT, SPECT, myocardial perfusion imaging

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a major clinical problem affecting both developed and developing countries. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) remains one of the most frequently utilized testing modalities for establishing the diagnosis of CAD [1]. In the last few decades SPECT MPI has undergone major advances with the advent of cadmium zinc telluride (CZT) solid-state detector technology, specialized collimators, and software-based resolution recovery resulting in improved performance when COMPARED conventional SPECT technology [2]. The Registry of Fast Myocardial Perfusion Imaging with Next Generation SPECT registry (REFINE SPECT) [3] is an international multicenter observational cohort study of patients with known or suspected CAD who underwent SPECT-MPI equipped with CZT technology.

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) score can be derived from ECG-gated low dose non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scans as a quantitative index of CAD. The CAC score has been shown to be a powerful prognosticator [4] with complemental prognostic value when used together with MPI [5]. Non-gated, low dose CT scans are frequently utilized in nuclear cardiology for performing accurate attenuation correction. The relevance and importance of CT attenuation correction is highlighted by the recent guidelines for the use of CT in hybrid nuclear/CT cardiac imaging [6]. Prior studies suggest, the CTs performed for attenuation correction (CTACs) can be used to quantify CAC burden with relatively good correlation between CAC score derived from CTACs and ECG gated dedicated CAC scoring CT.[7-9] Prior studies have also reported good agreement between visual estimation of CAC from low-dose CTACs in hybrid PET/CT and SPECT/CT with standard Agatston score.[8, 9] However, the prognostic utility of visually estimated CAC (VECAC) is unknown, specifically how it compares to CAC quantification by CAC score on CTACs (QCAC). Therefore, we sought to evaluate the predictive value and agreement between VECAC and QCAC by analyzing CTACs in REFINE SPECT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The REFINE SPECT registry [3] is an international multicenter observational cohort study of patients with known or suspected CAD with SPECT-MPI using CZT solid-state detector systems. From the REFINE SPECT Registry, patients without history of prior coronary stenting with CZT SPECT/CT performed at Yale New Haven Hospital were included after exclusion of those patients who did not undergo attenuation correction.

Clinical Data

We collected demographic data about the participants’ age, gender, body mass index, family history of CAD, smoking status and about the presence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, peripheral artery disease, history of previous myocardial infarction (MI) and prior coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. Resting blood pressure and heart rate were acquired prior to exercise or prior to stressor administration.

Image Acquisition and Protocol

All patients underwent stress perfusion and gated SPECT MPI using 99mTc-tetrofosmin with a Discovery NM 530c or Discovery 570c scanner (GE, Healthcare, Haifa, Israel). Stress testing was performed either by symptom-limited exercise treadmill stress testing or by pharmacological stress with regadenoson, adenosine or dobutamine as felt clinically appropriate. Static and gated images were acquired. Static images were reconstructed with and without attenuation correction, whereas gated images were reconstructed without attenuation correction. Baseline characteristics and stress test results including resting and stress heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and electrocardiogram findings along with exercise duration and stress symptoms were recorded by experienced nuclear cardiologists at the time of clinical interpretation.

CT attenuation map acquisition

CTAC scans were performed free breathing without ECG-gating in helical mode acquired with Discovery 570c for nuclear images acquired for both NM530c and Discovery 570c. The acquisition parameters were adjusted by the technologists according to the patient’s body mass index (BMI). In patients with BMI <40 kg/m2, the following parameters were used: tube current: 60 mA, tube voltage: 120 kV, rotation time: 0.4 seconds, pitch: 0.98, number of slices: 89, helical slice thickness: 2.5 mm, slice spacing: 2.5 mm. For patients with BMI ≥40 kg/m2 the tube current was adjusted to 150 mA. Images were reconstructed with 2.5-mm thickness using a full angle reconstruction.

Visual CTAC analysis

At the time of clinical study interpretation, one of 10 expert readers involved in the clinical interpretation reviewed CTAC images and visually graded CAC (VECAC) on a 4-level scale, classifying patients as having zero (0), mild (1), moderate (2) or severe (3) calcifications in 4 vascular territories (left main, left anterior descending, left circumflex and right coronary). Overall VECAC grade was defined by the summary of vessel specific scores yielding a possible score of 0–12 for each person [10]. Overall VECAC was defined based in summary score as mild (1-2), moderate (3-5) or severe (>5).

CTAC calcium scoring

CAC scoring of CTAC scans was performed by an experienced observer (CNMT technologist) using standard clinical tool (Cardiac Suite Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA) using a standard 130 HU threshold.[7, 11] For each patient, the CTAC Agatston score (QCAC) was computed. Visually estimated CAC was correlated with categorized QCAC (zero: 0, mild: 1-99, moderate: 100-399, severe: ≥400).

Outcomes

The primary end point was MACE which included all-cause mortality, nonfatal MI, or late coronary revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass surgery >90 days after SPECT imaging). MACE was determined by review of electronic medical records [3]. The first occurring MACE was considered the primary end point.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared by the χ2 test, and continuous variables were compared by the Student t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test, as appropriate. Agreement between VECAC and QCAC was determined using linearly-weighted kappa statistics. Using receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and pairwise comparisons according to Delong et al. [12] the predictive performance for 2-year MACE was compared for VECAC versus QCAC after censoring patients without 2-year follow-up. Harrel’s C-statistic was also performed to compare the predictive performance of VECAC versus QCAC. Kaplan-Meier analysis was performed, and survival curves were compared with the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 27.0.0 (Microsoft Inc, College Station, TX) or R version 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A 2-sided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

The final study population comprised 4,236 patients after exclusion of studies without CTAC or with non-diagnostic CTAC (n=229) and patients with prior coronary stenting (n=549) from the total of 4,988 Yale New Haven Hospital studies included in the REFINE-SPECT registry.

Table 1. summarizes the baseline characteristics of subjects. During the median follow-up of 25 months (95% confidence interval: 24 - 25 months) 372 patients (9%) experienced MACE including 219 deaths, 124 Mis and 81 late revascularizations (66 percutaneous coronary interventions and 15 coronary artery bypass surgeries). Subjects who experienced events were older, more likely to be male, had lower body mass index, lower diastolic blood pressure readings, higher rate of smoking and had higher rate of cardiovascular comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, peripheral artery disease, prior MI and prior surgical revascularization. In addition, subjects who experienced events were more likely to undergo pharmacological testing and had lower stress heart rates and stress systolic and diastolic blood pressures (Table 2). In addition, CTAC calcium score was higher (median [interquartile range]: 502 [69-1228] versus 35 [0-380]) and visual severe calcifications were more frequently observed in patients who experienced MACE (47 % vs. 20%).

Table 1.

Categorical variables shown as numbers (%), continuous variables shown as median values (interquartile range). Abbreviations: MACE: major adverse cardiac events, BMI: body mass index, CAD: coronary artery disease, PAD peripheral artery disease, MI: myocardial infarction, CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting, SBP: systolic blood pressure, DBP: diastolic blood pressure, HR: heart rate

| N | Overall n=4,236 |

MACE n=372 |

No MACE N=3,864 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 64 (56 – 73) | 70 (60-79) | 63 (55-72) | <0.001 |

| Female | 1,998 (47%) | 132 (36%) | 1,866 (48%) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.3(25.5 – 34.00) | 28.1 (24.2-32.8) | 29.4 (25.6-34.1) | <0.001 |

| Family history of CAD | 624 (15%) | 35 (9%) | 589 (15%) | 0.002 |

| Smoking | 837 (20%) | 82 (22%) | 755 (20%) | 0.25 |

| Hypertension | 2,626 (62%) | 250 (67%) | 2,376 (62%) | 0.03 |

| Dyslipidemia | 2,162 (51%) | 203 (55%) | 1,959 (51%) | 0.16 |

| Diabetes | 1,059 (25%) | 128 (34%) | 931 (24%) | <0.001 |

| PAD | 765 (18%) | 126 (34%) | 639 (17%) | <0.001 |

| History of MI | 165 (4%) | 28 (8%) | 137 (4%) | <0.001 |

| History of CABG | 180 (4%) | 44 (12%) | 136 (4%) | <0.001 |

| Resting SBP, mmHg | 138 (125 – 152) | 139 (126-158) | 138 (124-152) | 0.10 |

| Resting DBP, mmHg | 80 (73 – 86) | 78 (69-85) | 80 (74-86) | <0.001 |

| Resting HR, beats/min | 71 (63 – 80) | 71 (63-80) | 71 (63-80) | 0.63 |

Table 2.

Categorical variables shown as numbers (%), continuous variables shown as median values (interquartile range). Abbreviations: MACE (major adverse cardiac events), HR: heart rate, SBP: systolic blood pressure, DBP: diastolic blood pressure

| N | Overall n=4,236 |

MACE n=372 |

No MACE N=3,864 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress type | Exercise | 1,591 (38%) | 49 (13%) | 1,542 (40%) | <0.001 |

| Regadenoson | 2,493 (59%) | 305 (82%) | 2,188 (57%) | ||

| Adenosine | 113 (3%) | 10 (3%) | 103 (3%) | ||

| Dobutamine | 39 (1%) | 8 (2%) | 31 (1%) | ||

| Stress HR, beats/min | 109 [90 – 146] | 92 (81 – 111) | 112 (92-148) | <0.001 | |

| Stress SBP, mmHg | 153 (131-175) | 139 (119-162) | 155 (133-176) | <0.001 | |

| Stress DBP, mmHg | 80 (71-88) | 72 (64-81) | 80 (72-89) | <0.001 | |

| ECG response to test | Negative | 3,018 (71%) | 240 (65%) | 2,778 (72%) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 403 (10%) | 29 (8%) | 374 (10%) | ||

| Equivocal | 250 (6%) | 17 (5%) | 233 (6%) | ||

| Non-diagnostic | 565 (13%) | 86 (23%) | 479 (12%) | ||

| Calcium score | 49 (0 – 462) | 502 (69-1,228) | 35 (0-380) | <0.001 | |

| VECAC | Zero | 1,581 (37%) | 55 (15%) | 1,526 (40%) | <0.001 |

| Mild | 958 (23%) | 60 (16%) | 898 (23%) | ||

| Moderate | 751 (18%) | 82 (22%) | 669 (17%) | ||

| Severe | 946 (22%) | 175 (47%) | 771 (20%) | ||

Correlation between visual coronary calcium estimation and CTAC calcium scoring

A high degree of association was observed between VECAC and categorized QCAC, with 73% of VECACs in the same category as QCAC and 98% within one category. There was substantial agreement between VECAC and QCAC (weighted kappa: 0.78 with 95% confidence interval: 0.76-0.79), p < 0.001, Figure 1). High weighted kappa statistics were observed for all readers with over 500 reads (n=3 readers, range of weighted kappa: 0.75-0.80, Figure 2), however a variation was observed in the reading patterns when individual readers were compared to each other. The other 7 readers all had below 500 reads (range: 11-370).

Figure 1.

Correlation between visually estimated coronary artery calcification (VECAC) and coronary artery calcifications quantified by calcium score on computed tomography attenuation correction CTACs (QCAC) obtained for SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging. CI: confidence interval

Figure 2.

Individual correlations for visually estimated coronary artery calcification (VECAC) and coronary artery calcifications quantified by calcium score on computed tomography attenuation correction CTACs (QCAC) for readers with over 1,000 reads. CI: confidence interval

Predictive value of visual and quantitative coronary calcium evaluation

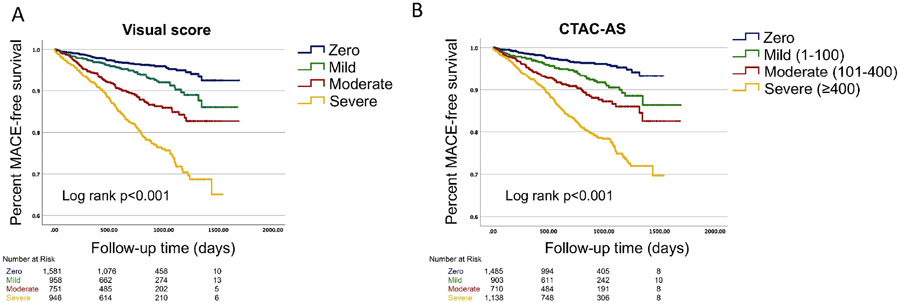

In survival analysis, both VECAC and QCAC were associated with adverse MACE (Figure 3, log rank p<0.001). In univariate Cox-regression analysis both VECAC (Figure 4, hazard ratio [HR] versus zero CAC; mild: 1.80 [95% CI: 1.25-2.59], moderate: 3.22 [95% CI: 2.29-4.54], severe: 5.77 [95% CI: 4.26-7.81]) and QCAC (HR versus zero QCAC; mild: 2.02 [95% CI: 1.37-2.96], moderate: 3.05 [95% CI: 2.11-4.42], severe: 5.53 [95% CI: 4.02-7.60]) were predictors of MACE. The ROC area under the curve (AUC) for 2-year-MACE was similar for VECAC when compared to QCAC (0.694 versus 0.691 respectively, p=0.70, Figure 5). In addition, c-statistic was similar for MACE for the summed VECAC score and the quantitative CAC score (0.688 and 0.689, respectively).

Figure 3.

Survival estimates for major adverse event (MACE)-free survival based on visual coronary calcium estimation (Panel A) and attenuation computed tomography calcium score (QCAC, Panel B).

Figure 4.

Forest plots of hazard ratios (HR) of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) based on visual coronary calcium (CAC) estimation (Panel A) and quantitative calcium score (Panel B). CI: confidence interval.

Figure 5.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for the prediction of major adverse cardiac events (MACE) at 2 years follow-up time based on visual coronary calcium estimation and attenuation computed tomography calcium score (QCAC). AUC area under the curve, CI: confidence interval

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge this is the first study to demonstrate the prognostic value of visual coronary calcification estimation of CTACs obtained for SPECT MPI in comparison to QCAC in a relatively large patient cohort. We have confirmed that visual assessment of CAC on low-dose CTAC scans provides good estimation of QCAC. Our data also suggests that visually assessed CAC has similar prognostic value for MACE in comparison to QCAC in patients undergoing SPECT MPI. Our findings further support the expanding use of hybrid myocardial perfusion imaging systems.

CAC scoring by non-contrast CT can accurately estimate CAC burden within the coronary arteries which can serve as a surrogate for CAD [13]. CAC score provides predictive value beyond traditional cardiovascular risk assessment tools [13, 14]. Our group [5] and other investigators [15, 16] recently showed that CAC scoring on dedicated ECG-gated non-contrast CT scans increases the diagnostic accuracy of myocardial perfusion imaging for the detection of obstructive coronary artery disease. In addition, limited studies suggest that dedicated CAC score and myocardial perfusion can predict adverse cardiovascular events independently of each other providing complimentary information [17, 18].

With hybrid SPECT/CT imaging and PET myocardial perfusion imaging a low-dose CTAC is performed to correct for attenuation. This attenuation CT may be used for qualitative estimation of CAC. Small studies previously demonstrated a good correlation between visually assessed coronary calcifications and dedicated CAC score derived from calcium scoring CT [7, 8]. Similar to our findings, the study by Einstein et al. showed a high degree of association between VECAC and categorized dedicated CAC score, with 63% of VECACs in the same category as the dedicated CAC score category and 93% within one category [8]. Our findings show that despite the good correlation between VECAC and categorized QCAC for each individual readers above 500 reads, a difference in reading pattern was observed likely related to stylistic differences between readers. Beyond the qualitative assessment, recently the feasibility of CAC quantification on CTACs has been demonstrated with excellent correlation with standard Agatston scores [7, 9, 19-23]. The computation of QCAC can potentially eliminate the inter-reader variability rooted in different reporting styles. In addition, recently published studies suggest that deep learning algorithms can be employed for faster computation of CTAC calcium scores without losing significant diagnostic or prognostic accuracy [21, 22]. The main advantage for leaving out the acquisition of a dedicated CAC scoring CT is the reduction in scan time, financial burden, and radiation dose.

The visual estimation of CAC on attenuation CT has been shown to improve diagnostic accuracy of MPI [24] in addition to carrying significant prognostic information beyond perfusion imaging [24-26]. VECAC has been demonstrated high degree of interobserver reproducibility with readers reporting identical scores in 65% of cases and scores within one category in over 93% of cases [8]. Growing data suggests that quantification of CAC from CTAC also carries significant prognostic value in predicting outcomes in patients undergoing MPI [21-23]. Our findings are in concert with prior observations showing that both qualitative and quantitative assessment of CAC on CTAC examinations carry significant prognostic value. Recognizing the value of CAC documentation on non-gated chest CT examinations, the recently published joint guidelines from the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and the Society of Thoracic Radiology recommends visual estimation of coronary calcification or computation of a non-gated Agatston score for all non-contrast CT examinations [27]. To streamline the analytic process, quantification of CAC could be performed by the technologist prior to image interpretation and could be further reviewed by the interpreting physician at the time of study interpretation. Optimization of CTAC acquisition protocols could improve consistency between different sites and could potentially provide more objective data about CAC.

Limitations

Despite the relatively large number of included patients, our study is a retrospective study with all the related inherent limitations. Only studies performed at a single academic center were included in the current study, however all analysis was performed in a core laboratory distinct from the imaging site with blinded image analysis. Our composite endpoint included late revascularization which is not considered to be a ‘hard’ cardiac event. However, it is important to mention that the primary outcome was driven by non-fatal MI and all-cause mortality. As a limitation, we also need to mention that our study employed high spatial resolution CT scanners, whereas CT scanners on the most frequently used hybrid SPECT-CT systems have limited contrast and temporal resolution, which may limit the generalizability of our findings.

CONCLUSION

In this study, visual assessment of CAC on low-dose CTAC scans obtained during SPECT/CT MPI provided good estimation of QCAC. In addition, QCAC had similar prognostic value for MACE in comparison to visually assessed CAC.

Acknowledgements:

Dr. Slomka participates in software royalties for QPS software at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and received research grant support from Siemens Medical Systems. Dr. Miller has received grant support from and is a consultant for GE Healthcare. All other authors have no relevant disclosures.

Funding

This research was supported in part by Grants R01HL089765 and R35HL161195 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institutes of Health (NHLBI/NIH) (PI: Piotr Slomka). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Dr. Slomka participates in software royalties for QPS software at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and received research grant support from Siemens Medical Systems. Dr. R. Miller has received grant support and consulting fees from Pfizer. Dr. E. Miller has received grant support from and is a consultant for GE Healthcare. All other authors have relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Yale Institutional Research Ethics Board provided approval for this study (HIC: 2000026611).

Consent to participate

The Yale Institutional Research Ethics Board provided consent waiver for this retrospective study. Patient who actively opted out from biomedical data research were not included in the study.

References

- [1].Ananthasubramaniam K, Arumugam P. Can we "REFINE" the art of predicting ischemia on SPECT myocardial perfusion imaging? J Nucl Cardiol. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Slomka PJ, Miller RJH, Hu LH, Germano G, Berman DS. Solid-State Detector SPECT Myocardial Perfusion Imaging. J Nucl Med. 2019;60:1194–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Slomka PJ, Betancur J, Liang JX, Otaki Y, Hu LH, Sharir T, et al. Rationale and design of the REgistry of Fast Myocardial Perfusion Imaging with NExt generation SPECT (REFINE SPECT). J Nucl Cardiol. 2020;27:1010–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, Bild DE, Burke G, Folsom AR, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1336–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brodov Y, Gransar H, Dey D, Shalev A, Germano G, Friedman JD, et al. Combined Quantitative Assessment of Myocardial Perfusion and Coronary Artery Calcium Score by Hybrid 82Rb PET/CT Improves Detection of Coronary Artery Disease. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1345–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Al-Mallah MH, Bateman TM, Branch KR, Crean A, Gingold EL, Thompson RC, et al. 2022 ASNC/AAPM/SCCT/SNMMI guideline for the use of CT in hybrid nuclear/CT cardiac imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Isgum I, de Vos BD, Wolterink JM, Dey D, Berman DS, Rubeaux M, et al. Automatic determination of cardiovascular risk by CT attenuation correction maps in Rb-82 PET/CT. J Nucl Cardiol. 2018;25:2133–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Einstein AJ, Johnson LL, Bokhari S, Son J, Thompson RC, Bateman TM, et al. Agreement of visual estimation of coronary artery calcium from low-dose CT attenuation correction scans in hybrid PET/CT and SPECT/CT with standard Agatston score. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1914–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mylonas I, Kazmi M, Fuller L, deKemp RA, Yam Y, Chen L, et al. Measuring coronary artery calcification using positron emission tomography-computed tomography attenuation correction images. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13:786–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Shemesh J, Henschke CI, Farooqi A, Yip R, Yankelevitz DF, Shaham D, et al. Frequency of coronary artery calcification on low-dose computed tomography screening for lung cancer. Clin Imaging. 2006;30:181–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wolterink JM, Leiner T, Takx RA, Viergever MA, Isgum I. Automatic Coronary Calcium Scoring in Non-Contrast-Enhanced ECG-Triggered Cardiac CT With Ambiguity Detection. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015;34:1867–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kelkar AA, Schultz WM, Khosa F, Schulman-Marcus J, O'Hartaigh BW, Gransar H, et al. Long-Term Prognosis After Coronary Artery Calcium Scoring Among Low-Intermediate Risk Women and Men. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e003742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lehmann N, Erbel R, Mahabadi AA, Rauwolf M, Mohlenkamp S, Moebus S, et al. Value of Progression of Coronary Artery Calcification for Risk Prediction of Coronary and Cardiovascular Events: Result of the HNR Study (Heinz Nixdorf Recall). Circulation. 2018;137:665–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Schepis T, Gaemperli O, Koepfli P, Namdar M, Valenta I, Scheffel H, et al. Added value of coronary artery calcium score as an adjunct to gated SPECT for the evaluation of coronary artery disease in an intermediate-risk population. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1424–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zampella E, Acampa W, Assante R, Nappi C, Gaudieri V, Mainolfi CG, et al. Combined evaluation of regional coronary artery calcium and myocardial perfusion by (82)Rb PET/CT in the identification of obstructive coronary artery disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45:521–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Engbers EM, Timmer JR, Ottervanger JP, Mouden M, Knollema S, Jager PL. Prognostic Value of Coronary Artery Calcium Scoring in Addition to Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomographic Myocardial Perfusion Imaging in Symptomatic Patients. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Patel KK, Peri-Okonny PA, Qarajeh R, Patel FS, Sperry BW, McGhie AI, et al. Prognostic Relationship Between Coronary Artery Calcium Score, Perfusion Defects, and Myocardial Blood Flow Reserve in Patients With Suspected Coronary Artery Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15:e012599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kaster TS, Dwivedi G, Susser L, Renaud JM, Beanlands RS, Chow BJ, et al. Single low-dose CT scan optimized for rest-stress PET attenuation correction and quantification of coronary artery calcium. J Nucl Cardiol. 2015;22:419–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pieszko K, Shanbhag AD, Lemley M, Hyun M, Van Kriekinge S, Otaki Y, et al. Reproducibility of quantitative coronary calcium scoring from PET/CT attenuation maps: comparison to ECG-gated CT scans. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49:4122–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pieszko K, Shanbhag AD, Killekar A, Miller RHJ, Lemley M, Y. O, et al. Deep Learning of Coronary Calcium Scores From PET/CT Attenuation Maps Accurately Predicts Adverse Cardiovascular Events. JACC Cardiovascular Imaging. 2022;in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Miller RJ, Pieszko K, Shanbhag A, Feher A, Lemley M, Killekar A, et al. Deep learning coronary artery calcium scores from SPECT/CT attenuation maps improves prediction of major adverse cardiac events. J Nucl Med. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Feher A, Pieszko K, Miller R, Lemley M, Shanbhag A, Huang C, et al. Integration of coronary artery calcium scoring from CT attenuation scans by machine learning improves prediction of adverse cardiovascular events in patients undergoing SPECT/CT myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Patchett ND, Pawar S, Miller EJ. Visual identification of coronary calcifications on attenuation correction CT improves diagnostic accuracy of SPECT/CT myocardial perfusion imaging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2017;24:711–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Trpkov C, Savtchenko A, Liang Z, Feng P, Southern DA, Wilton SB, et al. Visually estimated coronary artery calcium score improves SPECT-MPI risk stratification. Int J Cardiol Heart Vase. 2021;35:100827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chang SM, Nabi F, Xu J, Peterson LE, Achari A, Pratt CM, et al. The coronary artery calcium score and stress myocardial perfusion imaging provide independent and complementary prediction of cardiac risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1872–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hecht HS, Cronin P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Kazerooni EA, Narula J, et al. 2016 SCCT/STR guidelines for coronary artery calcium scoring of noncontrast noncardiac chest CT scans: A report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and Society of Thoracic Radiology. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2017;11:74–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]