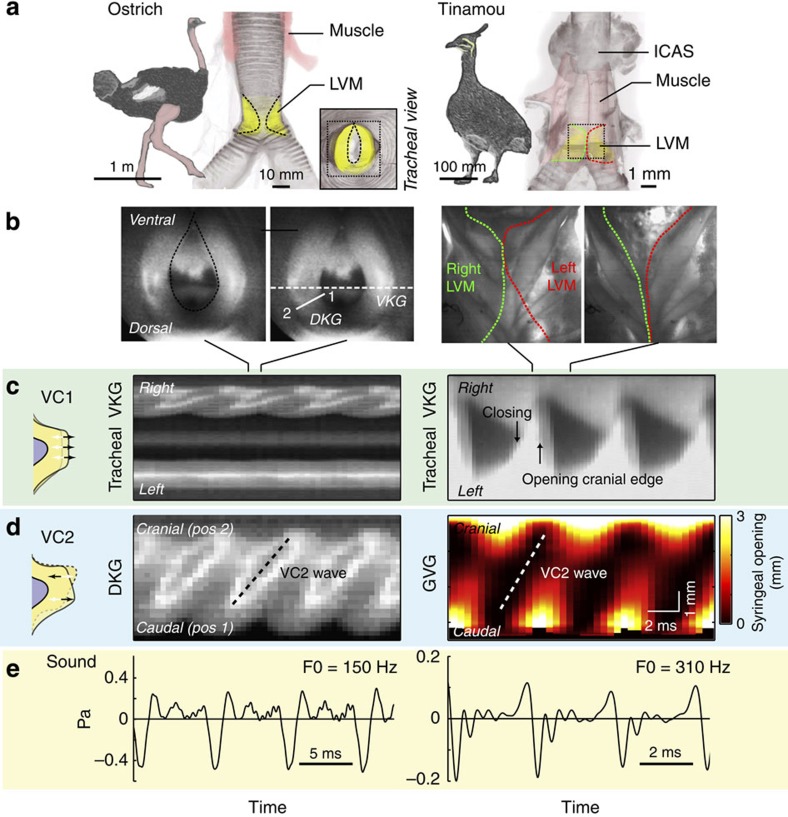

Figure 2. MEAD theory explains syringeal sound production in paleognaths.

(a) Three-dimensional syrinx geometry of the ostrich (Struthio camelus) and elegant-crested tinamou (Eudromia elegans) showing bone (grey), LVM (yellow) and muscles (pink). Both views are ventral. Muscle is rendered transparent in tinamou syrinx to show vibratory tissue. (b) High-speed imaging stills of endoscopic tracheal (ostrich) and transilluminated frontal views (tinamou) of the syrinx at two different phases during the oscillatory cycle. The region and location of these stills is indicated with a dotted box in a. For the ostrich the position of VKG analysis (dotted horizontal line) and DKG analysis (solid white line from point 1–2) presented in panel c is indicated. Transillumination provides sufficient detail to identify inner edges of right (green) and left (red) LVM in tinamou. (c) Evidence for medio-lateral vibrations (VC1) using tracheal endoscopic VKG. In the ostrich predominantly the right side vibrated. Full opening and closure of the cranial edge can be observed in tinamou. (d) Evidence for the caudo-cranial component (VC2) of the tissue wave as demonstrated by DKG for ostrich, and glottovibrogram for tinamou. (e) Synchronised acoustic waveforms.