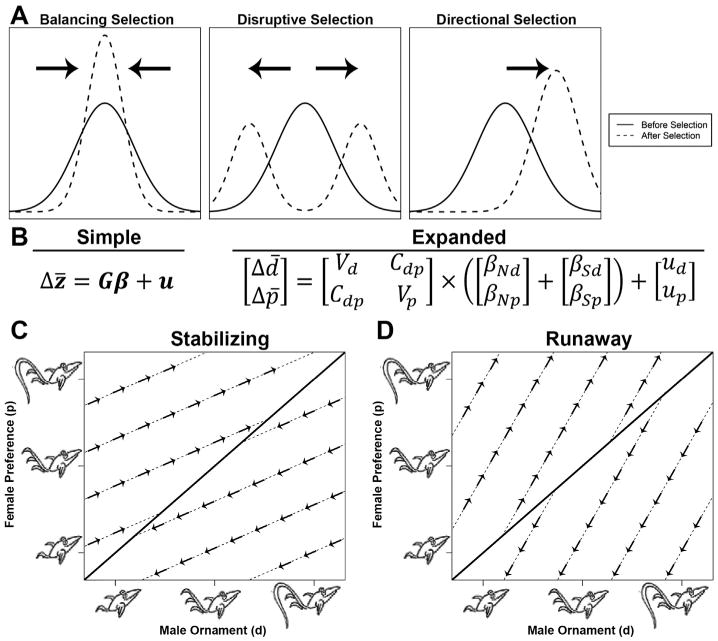

Fig. 1.

An introduction to trait selection and a summary of the G matrix model of sexual selection described by Lande [41] (and graphics adapted from Mead and Arnold [210]). (A) When a trait is under selection, three different modes are used to describe the direction that the mean moves: stabilizing selection (same mean, less variation), disruptive selection (moves towards the extremes), or directional selection (moves away from the mean along a single trajectory). (B) A mathematical representation of the G matrix, where in the simplified form a change in the mean of a trait (Δz̄) is equal to its genetic structure (G) times some selective force (β) plus a mutation constant (u). In the expanded form, the two traits being observed are a male display (d) and the corresponding female preference for the display (p). The G matrix is composed of the genetic variation for both d and p (Vd and Vp), and covariance (or genetic coupling) between the two traits (Cdp). Both natural (βN) and sexual (βS) selective forces can act on both the male display (βNd, βSd) and the female preference (βNp, βSp), and each trait is subject to independent mutations (ud and up). When there is weak or no genetic coupling (Cdp ∼ 0), the matrix simplifies such that the change in male display is only dependent on the direct selection acting on the display, and similarly for female preference. Therefore, male traits will evolve until female preferences are matched, represented by different evolutionary trajectories (dashed lines) converging towards an optimum (solid diagonal line) (C). However, when there is genetic coupling (Cdp > 0), selection on the male display can “pull” the female preference in a particular direction (indicated by the cross multiplication of Cdp and βd in B), and likewise for selection on the preference. Because of this deviation from independent selection towards the typical optimum, it is possible for male displays and female preferences to undergo “runaway selection” and evolve indefinitely, yielding ever increasingly more elaborate ornaments (D).