Abstract

Objectives To determine whether being elected to head of government is associated with accelerated mortality by studying survival differences between people elected to office and unelected runner-up candidates who never served.

Design Observational study.

Setting Historical survival data on elected and runner-up candidates in parliamentary or presidential elections in Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom, and United States, from 1722 to 2015.

Participants Elected and runner-up political candidates.

Main outcome measure Observed number of years alive after each candidate’s last election, relative to what would be expected for an average person of the same age and sex as the candidate during the year of the election, based on historical French and British life tables. Observed post-election life years were compared between elected candidates and runners-up, adjusting for life expectancy at time of election. A Cox proportional hazards model (adjusted for candidate’s life expectancy at the time of election) considered years until death (or years until end of study period for those not yet deceased by 9 September 2015) for elected candidates versus runners-up.

Results The sample included 540 candidates: 279 winners and 261 runners-up who never served. A total of 380 candidates were deceased by 9 September 2015. Candidates who served as a head of government lived 4.4 (95% confidence interval 2.1 to 6.6) fewer years after their last election than did candidates who never served (17.8 v 13.4 years after last election; adjusted difference 2.7 (0.6 to 4.8) years). In Cox proportional hazards analysis, which considered all candidates (alive or deceased), the mortality hazard for elected candidates relative to runners-up was 1.23 (1.00 to 1.52).

Conclusions Election to head of government is associated with a substantial increase in mortality risk compared with candidates in national elections who never served.

William Pitt the Younger, former prime minister of the United Kingdom. He dies in 1806 aged 46, 9 years after his first election

LISZT COLLECTION / ALAMY

Introduction

Election to public office may lead to accelerated aging due to stress of leadership and political life. A historical examination of medical records of US presidents suggested that they may age twice as quickly as the overall US population.1 2 A subsequent study that compared survival of US presidents with life expectancy in the overall population found no mortality difference between presidents and others.3 Although this finding could suggest that nationally elected leaders do not die prematurely, it may also suggest the opposite. Given their higher socioeconomic status, one might expect presidents to live longer than the general population on the basis of known inverse associations between social class and mortality.4 The fact that presidents do not live longer may suggest accelerated mortality compared with others of similar socioeconomic status.

To investigate this, we compared survival of nationally elected leaders from 17 countries with runner-up candidates who never served in office. We assumed that both types of candidates would be of similar socioeconomic status and baseline mortality risk but differ in exposure to serving as head of government.

Methods

Data sources and overview of approach

We assembled data on elected and runner-up candidates for national elections occurring in Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States, using online sources including Wikipedia and national lists of leaders (table 1). Because candidates frequently ran in multiple elections, we selected the last year each candidate ran for office, producing a candidate level dataset.

Table 1.

Study population

| Country | Elected leaders | Runners-up who did not serve in office | Total | Years | Head of government |

| Australia | 21 | 9 | 30 | 1901-2013 | Prime Minister |

| Austria | 21 | 32 | 56 | 1945-2013 | Chancellor |

| Canada | 16 | 12 | 28 | 1867-2011 | Prime Minister |

| Denmark | 15 | 9 | 24 | 1903-2015 | Prime Minister |

| Finland | 6 | 8 | 14 | 1919-2012 | President |

| France | 22 | 17 | 39 | 1873-2012 | President |

| Germany | 7 | 10 | 17 | 1949-2013 | Chancellor |

| Greece | 8 | 3 | 11 | 1956-2009 | Prime Minister |

| Ireland | 14 | 6 | 20 | 1922-2011 | Taoiseach |

| Italy | 17 | 20 | 38 | 1861-2013 | Prime Minister |

| New Zealand | 22 | 10 | 32 | 1855-2014 | Prime Minister |

| Norway | 9 | 16 | 25 | 1885-2013 | Prime Minister |

| Poland | 7 | 14 | 21 | 1922-2011 | Prime Minister |

| Spain | 14 | 33 | 47 | 1876-2015 | Prime Minister |

| Sweden | 8 | 9 | 17 | 1911-2014 | Prime Minister |

| UK | 34 | 19 | 53 | 1722-2015 | Prime Minister |

| USA | 38 | 34 | 72 | 1789-2012 | President |

| Total | 279 | 261 | 540 | 1722-2015 | – |

We compared observed life years from the time of last election between elected leaders and runners-up who never served, under the assumption that both groups had similar baseline mortality risk relative to the general population. Similar approaches have been used in mortality comparisons between winners and losers of specific events to identify the effect of winning that event on mortality (for example, comparisons of mortality among actors winning versus losing an Academy Award, baseball players inducted into the Hall of Fame, and Nobel Prize winners).5 6 7

Importantly, in many countries with parliamentary systems the head of government was not necessarily the majority party leader in earlier years but was instead selected after the elections took place (for example, Manuel Azaña in Spain). In other instances, the leader was appointed without any electoral experience (for example, Neville Chamberlain, in the United Kingdom, rose to the premiership after his predecessor retired). To account for these factors, we focused our analysis on candidates who ran in an election and either won an election and served or never won an election and never served. In countries with nominating processes, such as the United States, identifying candidates who “ran” was a straightforward exercise. However, in parliamentary systems, it was often less clear who “candidates” were—for these countries, we focused on people who served as party leaders at the time of election.

We compared mortality between the above two groups for two reasons. Firstly, candidates who served in office but lost or never ran in an election may systematically differ in mortality risk from candidates who won an election and served. Because our goal was to compare mortality among candidates who were as similar as possible in baseline mortality risk, but differed in whether they won an election and served in office, we restricted our analysis to elected leaders and similar unelected candidates who happened to never serve. Secondly, in very few countries today is the head of government not a party leader in some form. Hence, excluding candidates who were not elected to office in the now conventional manner allowed us to generalize our findings more appropriately to today’s candidates.

For both elected leaders and runners-up, we identified age at time of last election and age at death, the difference of which was the observed number of years a candidate lived from the time the election was held. We censored observed years alive after election for those candidates still alive by 9 September 2015. Because elected leaders and runner-up candidates may differ in age at last election, observed remaining life years may be affected by age related mortality differences alone. We therefore accounted for overall differences in life expectancy for someone of the same age and sex as the candidate in the general population. On the basis of a previous study,3 we obtained life expectancies for candidates from life tables of English male and female civilians (conditional on age and sex) for elections occurring after 1841 and from life tables of French male and female civilians before 1841.8 9 We chose the 17 countries that we analyzed because of their similarity to France and the United Kingdom, for which reliable life tables exist dating back to the 19th century.

Analysis

We did two candidate level statistical analyses. Firstly, we estimated a multivariable linear regression of observed years alive after last election as a function of a candidate’s life expectancy and whether he or she served as a head of government. Our sample consisted of 380 unique candidates who were deceased as of 9 September 2015 and who either ran for office and lost or ran for office and served. Our outcome was years alive after last election rather than age of death to overcome the “immortal time bias” that has been a problem in other studies.10

Secondly, we plotted Kaplan-Meier survival curves for elected leaders and runner-up candidates from year of last election until death. We then used a Cox proportional hazards model to estimate the mortality hazard associated with being elected leader. The model measured the time from last election until death (or end of the study period) for all candidates, adjusting for life expectancy at the time of election. Whereas the multivariable analysis included 380 deceased candidates, the hazard model included 160 additional candidates who were still alive as of 9 September 2015 (540 candidates in total; table 1 shows the distribution by country). The 95% confidence interval around reported estimates reflects 0.025 in each tail or P≤0.05.

Results

The earliest candidates in our sample stretched back to the 1722 UK parliamentary election (table 2 contains UK candidates; further materials are in the supplementary table). In that election, the losing candidate, Sir William Wyndham, was 34 and lived an additional 18 years, less than the 31 years that were expected for a 34 year old man in 1722. He did not run again, so 1722 was the election we used for him. The elected candidate, Robert Walpole, ran several more times, with his last appearance in 1741 (so that is the election selected for him). He lived only three years longer, less than the expected 11 years for a 65 year old in 1741.

Table 2.

Lifespans among elected leaders and runner-up candidates in UK prime minister elections, 1722-2015

| Candidate | Last election | Age at election | Age at death | Served in office | Expected/observed years alive after last election |

| Sir William Wyndham, 3rd Baronet | 1722 | 34 | 52 | No | 31/18 |

| Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke | 1734 | 56 | 73 | No | 16/17 |

| William Pulteney | 1741 | 57 | 80 | No | 16/23 |

| Robert Walpole | 1741 | 65 | 68 | Yes | 11/3 |

| Henry Pelham | 1747 | 53 | 59 | Yes | 18/6 |

| Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne and 1st Duke of Newcastle-under-Lyne | 1761 | 68 | 75 | Yes | 10/7 |

| Augustus Henry FitzRoy, 3rd Duke of Grafton | 1768 | 33 | 75 | Yes | 32/42 |

| Marques of Rockingham | 1780 | 50 | 52 | No | 20/2 |

| Lord Frederick North | 1780 | 48 | 60 | Yes | 21/12 |

| William Pitt “The Younger” | 1796 | 37 | 46 | Yes | 29/9 |

| Charles James Fox | 1802 | 53 | 57 | No | 18/4 |

| Henry Addington | 1802 | 45 | 86 | Yes | 23/41 |

| William Bentinck Duke of Portland | 1807 | 69 | 71 | Yes | 9/2 |

| Robert Banks Jenkinson Earl of Liverpool | 1826 | 56 | 58 | Yes | 16/2 |

| Marques of Lansdowne | 1830 | 50 | 82 | No | 20/32 |

| Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey | 1832 | 68 | 81 | Yes | 9/13 |

| Robert Peel | 1841 | 46 | 62 | Yes | 23/16 |

| John Russell | 1847 | 55 | 85 | Yes | 16/30 |

| Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston | 1865 | 80 | 80 | Yes | 5/0 |

| Archibald Philip Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, 1st Earl of Midlothian | 1895 | 48 | 82 | No | 21/34 |

| Robert Cecil | 1900 | 70 | 73 | Yes | 8/3 |

| Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman | 1906 | 70 | 71 | Yes | 9/1 |

| Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour | 1910 | 62 | 81 | No | 13/19 |

| Herbert Asquith | 1910 | 58 | 75 | Yes | 16/17 |

| John Robert Clynes | 1922 | 53 | 80 | No | 19/27 |

| Andrew Bonar Law | 1922 | 64 | 65 | Yes | 12/1 |

| James Ramsay MacDonald | 1929 | 63 | 71 | Yes | 12/8 |

| Arthur Henderson | 1931 | 68 | 72 | No | 10/4 |

| Stanley Baldwin | 1935 | 68 | 80 | Yes | 10/12 |

| Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill | 1951 | 77 | 90 | Yes | 6/13 |

| Anthony Eden | 1955 | 58 | 79 | Yes | 17/21 |

| Hugh Todd Naylor Gaitskell | 1959 | 53 | 56 | No | 21/3 |

| Harold Macmillan | 1959 | 65 | 92 | Yes | 13/27 |

| Alexander Frederick Douglas-Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel | 1964 | 61 | 92 | No | 15/31 |

| Sir Edward Richard George “Ted” Heath | 1970 | 54 | 89 | Yes | 20/35 |

| Leonard James Callaghan | 1979 | 67 | 92 | No | 12/25 |

| Michael Mackintosh Foot | 1983 | 70 | 96 | No | 11/26 |

| Margaret Thatcher | 1987 | 62 | 87 | Yes | 16/25 |

| Neil Gordon Kinnock | 1992 | 50 | – | No | 27/23 |

| William Jefferson Hague | 2001 | 40 | – | No | 38/14 |

| Michael Howard, Baron Howard of Lympne | 2005 | 64 | – | No | 18/10 |

| Tony Blair | 2005 | 52 | – | Yes | 28/10 |

| James Gordon Brown | 2010 | 59 | – | No | 23/5 |

| Edward Samuel “Ed” Miliband | 2015 | 46 | – | No | 35/0 |

| David Cameron | 2015 | 49 | – | Yes | 33/0 |

Expected years of life after national election were based on average person of same age and sex as candidate, taken from historical life tables as described in Methods. Premature death was defined by whether candidate lived strictly less than would be expected for average person in population of same age and sex as candidate (that is, observed<expected life expectancy). Living candidates who exceeded their demographically determined life expectancy were identified as non-premature deaths. Periods reflect candidates who were elected after 2013, last year in life tables. Dashes indicate still living candidate.

Without adjustment for life expectancy at time of last election, elected leaders lived 4.4 (95% confidence interval 2.0 to 6.6) fewer years than runners-up. However, elected leaders were also on average 3.8 years older in the year of their last election compared with runners-up (59.2 v 55.4). After adjustment for life expectancy, elected leaders lived 2.7 (0.6 to 4.8) fewer years than runners-up.

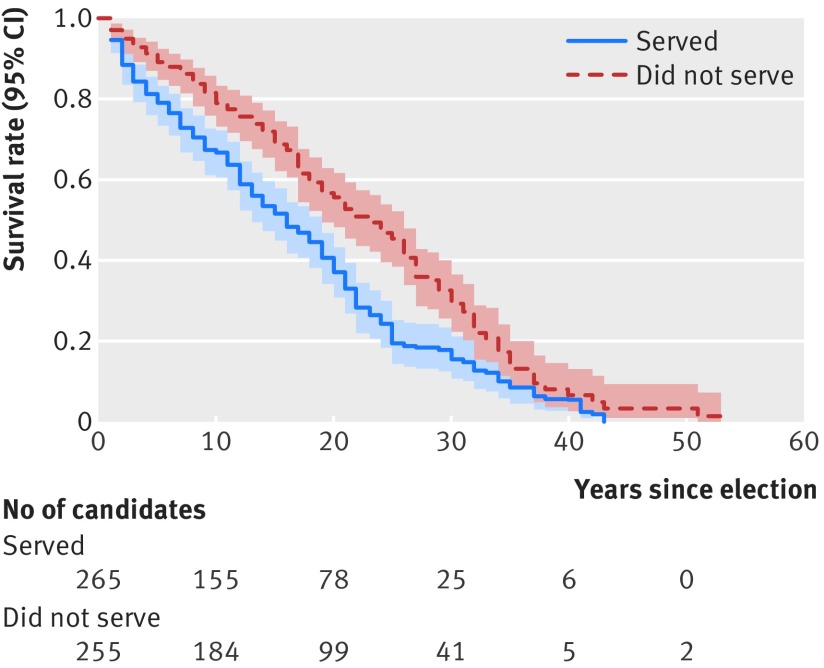

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed statistically significantly higher mortality among elected leaders compared with runners-up, according to a log-rank survival equality test (χ2=19.8; P<0.001) (fig 1). In Cox proportional hazards analysis, which adjusted for a candidate’s life expectancy at last election, we estimated a mortality hazard of 1.23 (95% confidence interval 1.00 to 1.52) for elected leaders versus runners-up.

Fig 1 Kaplan-Meier survival curves for candidates elected to head of government and runners-up

Discussion

It has been suggested that heads of government experience accelerated aging and premature mortality. Analyzing historical election data from 17 countries spanning more than two centuries, we found that being elected to head of government was associated with a substantive increase in mortality compared with runners-up.

Our study contributes to previous analyses of mortality among US presidents and vice presidents and may help to explain why previous findings have been mixed.3 6 One study of US presidents found no difference in survival after election compared with men of the same age in the general population.3 However, because presidents (or those in the same socioeconomic strata) may have lower mortality than the general population, a failure to detect a mortality difference could suggest that presidency is associated with higher than expected mortality. Analysis of a single country’s elections may also be underpowered. Another study that compared mortality among US presidents and vice presidents versus presidential and vice presidential candidates found that election to office was associated with earlier death among both presidents and vice presidents.6 This study did not account for age at election, which may confound analysis if elected candidates were on average older than runner-up candidates, as we found to be true. Moreover, the study was limited to US candidates.

Limitations of study

Our study had several limitations. Firstly, although we included data from 17 countries, our results may not generalize to other countries. Secondly, we could not do country specific analyses. In both politics and statistics, power is critical. In post hoc calculations, the statistical power to detect an absolute difference of 4.4 post-election life years (our estimated difference between elected and runner-up candidates) in a single country comparison of 34 elected and 19 runner-up candidates (the UK sample) was 14%. Thirdly, our database was created by manual review of online sources and reflected information from electoral norms that varied across countries and time. Without detailed knowledge of each country’s electoral histories and politics, measurement errors in our database could arise, although these should not be systematic. Fourthly, by focusing on last election, our method may introduce a “healthy worker bias” if elected leaders have a lower health threshold for running for re-election.11 12

Finally, we compared mortality between elected leaders and runners-up under the assumption that the two groups do not differ in baseline mortality risk. However, both groups, who are heavily involved in politics, may experience accelerated mortality relative to similarly well off people not involved in politics, which would bias our estimates toward zero. Similarly, in some countries, party candidates reflected different socioeconomic strata (the UK Labour Party historically featured leaders who began as farmers and miners, in contrast to the classically aristocratic Tories) and therefore may differ in baseline mortality risk.

Conclusion

We found that heads of government had substantially accelerated mortality compared with runner-up candidates. Our findings suggest that elected leaders may indeed age more quickly.

What is already known on this topic

Politicians elected to head of government may experience accelerated aging and premature mortality

However, existing studies have focused on US presidents alone and findings have been mixed

A historical analysis of mortality among a large group of world leaders has not been done

What this study adds

Analysis of historical election data from 17 countries showed that being elected to and serving in public office was associated with a substantive increase in mortality risk compared with runner-up candidates

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary table

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design and conduct of the study; data collection and management; analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. ABJ is the guarantor.

Funding: ABJ had support from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (NIH early independence award, grant 1DP5OD017897-01). The research conducted was independent of any involvement from the sponsors of the study. Study sponsors were not involved in study design, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: ABJ had support from the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: All data were publicly available and the study was exempt from human subjects review at Harvard Medical School.

Transparency statement: The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

References

- 1.Park M. Advice to Obama on battling presidential aging. 2009. www.cnn.com/2009/HEALTH/01/06/presidential.health.aging/index.html?_s=PM:HEALTH.

- 2.Hanna J. Do presidents age faster in office? 2011. http://edition.cnn.com/2011/POLITICS/08/04/presidents.aging/.

- 3.Olshansky SJ. Aging of US presidents. JAMA 2011;306: 2328-9. 10.1001/jama.2011.1786 22147378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marmot MG, Smith GD, Stansfeld Set al. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet 1991;337: 1387-93. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-K 1674771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Redelmeier DA, Singh SM. Survival in Academy Award-winning actors and actresses. Ann Intern Med 2001;134: 955-62. 10.7326/0003-4819-134-10-200105150-00009 11352696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Link BG, Carpiano RM, Weden MM. Can honorific awards give us clues about the connection between socioeconomic status and mortality?Am Sociol Rev 2013;78: 192-21210.1177/0003122413477419. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rablen MD, Oswald AJ. Mortality and immortality: the Nobel Prize as an experiment into the effect of status upon longevity. J Health Econ 2008;27: 1462-71. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.06.001 18649962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Human Mortality Database. U.K., England & Wales Civilian Population. 2015. www.mortality.org/cgi-bin/hmd/country.php?cntr=GBRCENW&level=1.

- 9.The Human Mortality Database. France, Civilian population. 2015. www.mortality.org/cgi-bin/hmd/country.php?cntr=FRACNP&level=1.

- 10.Sylvestre MP, Huszti E, Hanley JA. Do OSCAR winners live longer than less successful peers? A reanalysis of the evidence. Ann Intern Med 2006;145: 361-3, discussion 392. 10.7326/0003-4819-145-5-200609050-00009 16954361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldblatt P, Fox J, Leon D. Mortality of employed men and women. Am J Ind Med 1991;20: 285-306. 10.1002/ajim.4700200303 1928107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMichael AJ. Standardized mortality ratios and the “healthy worker effect”: Scratching beneath the surface. J Occup Med 1976;18: 165-8. 10.1097/00043764-197603000-00009 1255276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary table