Abstract

The hippocampal formation (HPC) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) have well-established roles in memory encoding and retrieval. However, the mechanisms underlying interactions between the HPC and mPFC in achieving these functions is not fully understood. Considerable research supports the idea that a direct pathway from the HPC and subiculum to the mPFC is critically involved in cognitive and emotional regulation of mnemonic processes. More recently, evidence has emerged that an indirect pathway from the HPC to the mPFC via midline thalamic nucleus reuniens (RE) may plays a role in spatial and emotional memory processing. Here we will consider how bidirectional interactions between the HPC and mPFC are involved in working memory, episodic memory and emotional memory in animals and humans. We will also consider how dysfunction in bidirectional HPC-mPFC pathways contributes to psychiatric disorders.

Keywords: prefrontal cortex, memory, emotion, context, extinction, working memory, PTSD

Introduction

Episodic memories represent past autobiographical events and include rich details about the context in which those events occur. For example, a memory of your high school prom might include where the dance was held, when it occurred, how you traveled to the dance, and of course, who your date was for the evening. The contextual information encoded during an experience supports the later retrieval of that information, a phenomenon supported by encoding specificity (Tulving and Thomson, 1973) and contextual retrieval (Hirsh, 1974). That is, the content of what is remembered about a particular event is often critically dependent on where that memory is retrieved. Deficits in contextual retrieval are associated with memory impairments accompanying a variety of neural insults including age-related dementia, traumatic brain injury, stroke, and neurodegenerative disease. As such, understanding the neural circuits mediating contextual retrieval is essential for targeting interventions to alleviate memory disorders and associated cognitive impairments.

Decades of research in both humans and animals have revealed that two brain areas, the hippocampus (HPC) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), are essential for the encoding and retrieval of episodic memories (Kennedy and Shapiro, 2004; Hasselmo and Eichenbaum, 2005; Diana et al., 2010; Preston and Eichenbaum, 2013). Indeed, considerable data suggests that communication between these brain areas is essential for episodic memory processes (Simons and Spiers, 2003; Preston and Eichenbaum, 2013). Anatomically, neurons in the HPC have a robust projection to the mPFC, including the infralimbic (IL) and prelimbic (PL) cortices in rats (Swanson and Kohler, 1986; Jay and Witter, 1991; Thierry et al., 2000; Varela et al., 2014). In primates, there are projections that originate from hippocampal CA1 and terminate in the orbital and medial frontal cortices (areas 11, 13, 14c, 25 and 32; Zhong et al., 2006). These PFC connectivity patterns seem to be similar in humans and monkeys; for example, both humans and monkeys have fimbria/fornix fibers (which originate from the hippocampus and subiculum) terminating in the medial orbital PFC (Cavada et al., 2000; Croxson et al., 2005). For these reasons, models of episodic retrieval have largely focused on the influence of contextual representations encoded in the HPC on memory retrieval processes guided by the mPFC (Maren and Holt, 2000; Hasselmo and Eichenbaum, 2005; Ranganath, 2010). Yet emerging evidence suggests that the mPFC itself may be critical for directing the retrieval of context-appropriate episodic memories in the HPC (Navawongse and Eichenbaum, 2013; Preston and Eichenbaum, 2013). This suggests that indirect projections from the mPFC to HPC may be involved in episodic memory, including contextual retrieval (Davoodi et al., 2009, 2011; Hembrook et al., 2012; Xu and Südhof, 2013). Moreover, abnormal interactions between the HPC and mPFC are associated with decreased mnemonic ability as well as disrupted emotional control, which are major symptoms of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, depression, specific phobia, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Sigurdsson et al., 2010; Godsil et al., 2013; Maren et al., 2013). Here we will review the anatomy and physiology of the HPC-mPFC pathway in relation to memory and emotion in an effort to understand how dysfunction in this network contributes to psychiatric diseases.

Anatomy and Physiology of Hippocampal-Prefrontal Projections

It has long been appreciated that there are both direct monosynaptic projections, as well as indirect polysynaptic projections between the HPC and the mPFC (Hoover and Vertes, 2007). In rats, injections of retrograde tracers into different areas of the mPFC robustly label neurons in the VH and subiculum (Jay et al., 1989; Hoover and Vertes, 2007). In addition, injections of the anterograde tracer, Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin (PHA-L), into the HPC reveal direct projections to the mPFC (Jay and Witter, 1991). Hippocampal projections to the mPFC originate primarily in ventral CA1 and ventral subiculum; there are no projections to the mPFC from the dorsal hippocampus or dentate gyrus. Therefore, the direct functional interactions we discuss below focus on ventral hippocampal and subicular projections to the mPFC. Hippocampal projections course dorsally and rostrally through the fimbria/fornix, and then continue in a rostro-ventral direction through the septum and the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), to reach the IL, PL, medial orbital cortex, and anterior cingulate cortex (Jay and Witter, 1991; Cenquizca and Swanson, 2007). Afferents from CA1 and the subiculum are observed throughout the entire rostro-caudal extent of the mPFC, with only sparse projections to the medial orbital cortex.

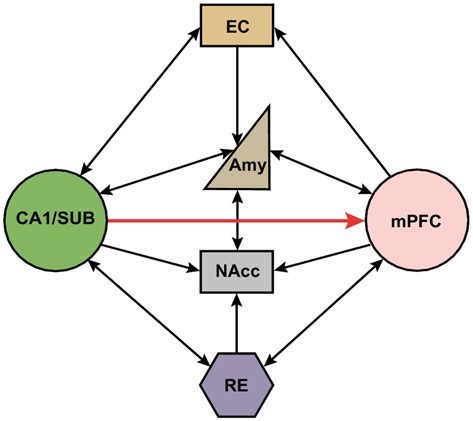

Indirect multi-synaptic pathways from the HPC to mPFC include projections through the NAcc and ventral tegmental area (VTA), amygdala, entorhinal cortex (EC), and midline thalamus (Maren, 2011; Russo and Nestler, 2013; Wolff et al., 2014). These complex multi-synaptic pathways from both subcortical and cortical areas are critically involved in higher cognitive functions that are related to several major psychiatric disorders. For example, it has been reported that NAcc receives convergent synaptic inputs from the PFC, HPC and amygdala (Groenewegen et al., 1999). This cortical-limbic network has been shown to mediate goal-directed behavior by integrating HPC-dependent contextual information and amygdala-dependent emotional information with cognitive information processed in the PFC (Goto and Grace, 2005, 2008). In addition, the mPFC projects to the thalamic nucleus reuniens (RE), which in turn has dense projections to the HPC (Varela et al., 2014). Importantly, this projection is bidirectional, which provides another route for the HPC to influence the mPFC (Figure 1). Interestingly, it has been shown that single RE neurons send collaterals to both the HPC and mPFC (Hoover and Vertes, 2012; Varela et al., 2014). This places the RE in a key position to relay information between the mPFC and HPC to coordinate their functions (Davoodi et al., 2009, 2011; Hembrook et al., 2012; Hoover and Vertes, 2012; Xu and Südhof, 2013; Varela et al., 2014; Griffin, 2015; Ito et al., 2015). The mPFC also has strong projections to the EC, which in turn has extensive reciprocal connections with hippocampal area CA1 and the subiculum (Vertes, 2004; Cenquizca and Swanson, 2007). Interestingly, the CA1 and subiculum send direct projections back to the mPFC, allowing these areas to form a functional loop that enables interactions between cortical and subcortical areas during memory encoding and retrieval (Preston and Eichenbaum, 2013).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of direct and indirect neural circuits between the medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus/subiculum. Hippocampal area CA1 and the subiculum (SUB) have strong direct projections to the mPFC, but there are no direct projections from the mPFC back to the HPC. The reuniens (RE) and amygdala has reciprocal connections with both the mPFC and HPC. NAcc receives inputs from mPFC, HPC, RE and amygdala. mPFC also project to entorhinal cortex (EC) which in turn has reciprocal projections with HPC. SUB, subiculum; EC, entorhinal cortex; Amy, amygdala; NAcc, nucleus accumbens; RE, nucleus reuniens; mPFC, medial prefrontal cortex.

The physiology of projections between the HPC and mPFC has been extensively investigated in rodents. These projections consist of excitatory glutamatergic pyramidal neurons that terminate on either principle neurons or GABAergic interneurons within the mPFC (Jay et al., 1992; Carr and Sesack, 1996; Tierney et al., 2004). Electrical stimulation in hippocampal area CA1 or the subiculum produces a monosynaptic excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) followed by fast and slow inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs); the latter are due to both feedforward (Jay et al., 1992; Tierney et al., 2004) and feedback inhibition (Dégenètais et al., 2003). Excitatory responses evoked in mPFC neurons by electrical stimulation of the HPC are antagonized by CNQX but not by AP5, indicating that these responses are AMPA-receptor dependent (Jay et al., 1992). Hippocampal synapses in the mPFC exhibit activity-dependent plasticity including long-term potentiation (LTP), long-term depression (LTD), and depotentiation (Laroche et al., 1990, 2000; Jay et al., 1996; Burette et al., 1997; Takita et al., 1999). These forms of plasticity are NMDA receptor-dependent and involve activation of serine/threonine kinases such as CaMKII, PKC, and PKA (Dudek and Bear, 1992; Bliss and Collingridge, 1993; Jay et al., 1995, 1998; Burette et al., 1997; Takita et al., 1999).

Within the indirect mPFC-RE-HPC pathway, a large proportion of RE projection neurons are glutamatergic (Bokor et al., 2002). RE stimulation produces strong excitatory effects on both HPC and PFC neurons (Dolleman-Van der Weel et al., 1997; Bertram and Zhang, 1999; McKenna and Vertes, 2004), suggesting that the RE is capable of modulating synaptic plasticity in both the HPC and mPFC (Di Prisco and Vertes, 2006; Eleore et al., 2011).

Working Memory

Both the HPC and mPFC have been implicated in working memory and mounting evidence suggests that communication between these two structures is critical for this process. Working memory is a short-term repository for task-relevant information that is critical for the successful completion of complex tasks (Baddeley, 2003). For example, in a spatial working memory task, animals must hold in memory the location of food rewards to navigate to those locations after a delay. Disconnection of the HPC and mPFC with asymmetric lesions disrupts spatial working memory (Floresco et al., 1997; Churchwell and Kesner, 2011). PFC lesions disrupt the spatial firing of hippocampal place cells whereas HPC lesions disrupt anticipatory activity of mPFC neurons in working memory tasks (Kyd and Bilkey, 2003; Burton et al., 2009). This suggests that interactions between the HPC and mPFC are crucial for this form of memory.

One index of the functional interaction of different brain regions is the emergence of correlated neural activity between them during behavioral tasks. For example, simultaneous recordings in the HPC and mPFC reveal synchronized activity during working memory tasks (Jones and Wilson, 2005; Siapas et al., 2005; Benchenane et al., 2010; Hyman et al., 2010). Hippocampal theta oscillations (4~10 Hz), which are believed to be important in learning and memory, are phase-locked with both theta activity and single-unit firing in the mPFC (Siapas et al., 2005; Colgin, 2011; Gordon, 2011). Medial prefrontal cortex firing lags behind the hippocampal LFP, suggesting that information flow is from the HPC to mPFC (Hyman et al., 2005, 2010; Jones and Wilson, 2005; Siapas et al., 2005; Benchenane et al., 2010; Sigurdsson et al., 2010). Interestingly, this synchronized activity is not static, but is modulated during tasks associated with working memory or decision-making. Recently, Spellman et al. (2015) used optogenetic techniques to manipulate activity in the VH-mPFC pathway during a spatial working memory task (Spellman et al., 2015). They found that in a “four-goal T-maze” paradigm, direct projections from the VH to the mPFC are crucial for encoding task-relevant spatial cues, at both neuronal and behavioral levels. Moreover, gamma activity (30~70 Hz) in this pathway is correlated with successful cue encoding and correct test trials and is disrupted by VH terminal inhibition. These findings suggest a critical role of the VH-mPFC pathway in the continuous updating of task-related spatial information during spatial working memory task.

Indirect projections from the mPFC back to the HPC are also involved in working memory. For example, lesions or inactivation of the RE cause deficits in both radial arm maze performance and a delayed-non-match-to-position task that has previously been shown to be dependent on both the HPC and mPFC. This suggests that the RE is required for coordinating mPFC-HPC interactions in working memory tasks (Porter et al., 2000; Hembrook and Mair, 2011; Hembrook et al., 2012). Recently, Ito et al. (2015) proposed that the mPFC→RE→sHPC projection is also crucial for representation of the future path during goal-directed behavior. Therefore, the RE is considered to be a key relay structure for long-range communication between cortical regions involved in navigation (Ito et al., 2015). Hence, both direct and indirect connections between the HPC and mPFC contribute to the hippocampal-prefrontal interactions important for working memory processes as well as spatial navigation.

Episodic Memory

Episodic memory is a long-term store for temporally dated episodes and the temporal-spatial relationships among these events (Tulving, 1983). These memories contain “what, where and when” information that place them in a spatial and temporal context. Although animals cannot explicitly report their experience, their knowledge of “what, where and when” information suggests that they also use episodic memories (Eacott and Easton, 2010). For example, animals can effectively navigate in mazes that require them to remember “what-where” information that is coupled to time (“when”; Fouquet et al., 2010). Considerable work indicates that the HPC and mPFC are critically involved in encoding and retrieval of episodic-like memories (Wall and Messier, 2001; Preston and Eichenbaum, 2013). Within the hippocampal formation (HPC), the perirhinal cortex (PRh) is thought to be crucial in signaling familiarity-based “what” information, whereas the parahippocampal cortex (PH) is involved in processing “where” events occur (Eichenbaum et al., 2007; Ranganath, 2010). Both the PRh and PH are connected with the EC, which in turn has strong reciprocal projections with the HPC and subiculum; this provides an anatomical substrate for the convergence of “what” and “where” information in the HPC (Ranganath, 2010). In support of this idea, studies have shown that hippocampal networks integrate non-spatial and spatial/contextual information (Davachi, 2006; Komorowski et al., 2009). More recently, there is evidence that neurons in hippocampal CA1 code both space and time, allowing animals to form conjoint spatial and temporal representations of their experiences (Eichenbaum, 2014). These findings suggest a fundamental role of the HPC for encoding episodic memories.

There is also considerable evidence that the mPFC contributes to episodic memory through cognitive or strategic control over other brain areas during memory retrieval. Although prefrontal damage does not yield severe impairments in familiarity-based recognition tests (Swick and Knight, 1999; Farovik et al., 2008), impairments are observed in tasks that require recollection-based memory, which rely on the retrieval of contextual and temporal information and resolution of interference (Shimamura et al., 1990, 1995; Dellarocchetta and Milner, 1993; Simons et al., 2002). It has been suggested that the mPFC is important for the integration of old and new memories that share overlapping features, whereas the HPC is more important in forming new memories (Dolan and Fletcher, 1997). These findings suggest that there is functional dissociation between the mPFC and HPC during episodic memory encoding and retrieval in some cases. However, these two structures interact with each other in order to complete memory tasks that require higher levels of cognitive control.

In line with this idea, human EEG studies have shown that HPC-mPFC synchrony is associated with memory recall. For instance, encoding of successfully recalled words was associated with enhanced theta synchronization between frontal and posterior regions (including parietal and temporal cortex), indicating that the interaction between these two areas is involved in memory encoding (Weiss and Rappelsberger, 2000; Weiss et al., 2000; Summerfield and Mangels, 2005). Furthermore, depth recordings in epilepsy patients reveal theta-oscillation coherence between the medial temporal lobe and PFC during verbal recall tests, suggesting that synchronized neural activity is involved in the encoding and retrieval of verbal memory (Anderson et al., 2010). Recently, work in monkeys has revealed that different frequency bands within the HPC and mPFC have different functional roles in object-paired associative learning (Brincat and Miller, 2015). Collectively, these data indicated that the HPC and mPFC interactions are dynamic during episodic memory encoding and retrieval.

Contextual Memory Retrieval

When humans and animals form new memories, contextual information associated with the experience is also routinely encoded without awareness (Tulving and Thomson, 1973). Contextual information plays an important role in memory retrieval since the content of what is often critically dependent on where that memory is retrieved (Hirsh, 1974; Maren and Holt, 2000; Bouton, 2002). This “contextual retrieval” process allows the meaning of a cue to be understood according to the context in which it is retrieved (Maren et al., 2013). For example, encountering a lion in the wild might be a life-threatening experience to someone, but seeing the same lion kept in its cage in the zoo might be an interesting (and non-threatening) experience. Therefore, the same cue in different contexts has totally different meanings. Contextual processing is highly adaptive because it resolves ambiguity during memory retrieval (Bouton, 2002; Maren et al., 2013; Garfinkel et al., 2014). Decades of research in both humans and animals have revealed that the HPC and mPFC are essential for contextual retrieval (Kennedy and Shapiro, 2004; Hasselmo and Eichenbaum, 2005; Diana et al., 2010; Maren et al., 2013). Humans and animals with disconnections in the HPC-mPFC network have deficits in retrieving memories that require either source memories or contextual information (Schacter et al., 1984; Shimamura et al., 1990; Simons et al., 2002). Thus, these brain regions are key components of a brain circuit involved in episodic memory, and connections between them are thought to support contextual retrieval.

Contextual retrieval is also critical for organizing defensive behaviors related to emotional memories (Bouton, 2002; Maren and Quirk, 2004; Maren et al., 2013). Learning to detect potential threats and organize appropriate defensive behavior while inhibiting fear when threats are absent are highly adaptive functions linked to emotional regulation (Maren, 2011). Deficits in emotional regulation often result in pathological fear memories that can further develop into fear and anxiety disorders, such as PTSD (Rasmusson and Charney, 1997). Studies indicate that fear memories are rapidly acquired and broadly generalized across contexts. In contrast, extinction memories often yield transient fear reduction and are bound to the context in which extinction occurs (Bouton and Bolles, 1979; Bouton and Nelson, 1994). After extinction, fear often relapses when the feared stimulus is encountered outside the extinction context-a phenomenon called fear “renewal” (Bouton, 2004; Vervliet et al., 2013).

Recent work indicates that the HPC-mPFC network plays a critical role in regulating context-dependent fear memory retrieval after extinction (Maren and Quirk, 2004; Maren, 2011; Orsini and Maren, 2012; Maren et al., 2013; Jin and Maren, 2015). Disconnection of the VH from the mPFC impairs fear renewal after extinction (Hobin et al., 2006; Orsini et al., 2011). Inactivation of the VH also modulates the activity of both interneurons and pyramidal neurons in the PL, and influences the expression of fear behavior in extinguished rats (Sotres-Bayon et al., 2012). Moreover, VH neurons projecting to both the mPFC and amygdala are preferentially involved in fear renewal (Jin and Maren, 2015), suggesting that VH might modulate memory retrieval by coupling activity in the mPFC and amygdala. Ultimately, the hippocampus appears to gate reciprocal mPFC-amygdala circuits involved in the expression and inhibition of fear (Herry et al., 2008; Knapska and Maren, 2009; Knapska et al., 2012). It has also been shown that the vmPFC-HPC network is involved in the context-dependent recall of extinction memories in humans (Kalisch et al., 2006; Milad et al., 2007). These observations support the idea that the HPC-mPFC pathway is critically involved in the context-specificity of fear memories, whereby the transmission of contextual information from the HPC to the mPFC generates context-appropriate behavioral response by interacting with the amygdala.

In animals, extinction learning induces a potentiation of VH-evoked potentials in the mPFC, while low frequency stimulation of the VH disrupts this potentiation and prevents extinction recall (Garcia et al., 2008). Chronic stress impairs the encoding of extinction by blocking synaptic plasticity in the HPC-mPFC pathway (Garcia et al., 2008; Maren and Holmes, 2015). In addition, it has been shown that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the VH-IL pathway is involved in extinction learning (Peters et al., 2010; Rosas-Vidal et al., 2014). Finally, histone acetylation in the HPC-IL network influences extinction learning (Stafford et al., 2012). These findings indicate that interactions between the HPC and mPFC are critical for encoding extinction memories.

HPC-PFC Interaction and Psychiatric Disorders

Abnormal functional interactions between the HPC and mPFC have been reported in several psychiatric disorders. For example, patients with schizophrenia exhibit aberrant functional coupling between the HPC and mPFC during rest and during working memory performance (Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2005; Zhou et al., 2008; Lett et al., 2014). This has been confirmed in animal models of schizophrenia, which also exhibit impaired working memory as well as decreased hippocampal-prefrontal synchrony (Sigurdsson et al., 2010). Abnormal interaction between the HPC and mPFC also causes deficits in emotional regulation associated with psychiatric disorders. Considerable evidence associates major depressive disorders with structural changes as well as functional abnormalities in hippocampal-prefrontal connectivity in both animals and humans (Bearden et al., 2009; Genzel et al., 2015). For example, the HPC and mPFC exhibit increased synchrony in anxiogenic environments (Adhikari et al., 2010; Schoenfeld et al., 2014; Abdallah et al., 2015). Moreover, traumatic experiences and pathological memories are linked to abnormal hippocampal-prefrontal interactions in PTSD patients, which in turn are associated with impaired contextual processing that mediates emotional regulation (Liberzon and Sripada, 2007). These seemingly distinct psychiatric disorders share similar symptoms: dysregulated interactions between the HPC and mPFC may be common to this shared symptomatology. Thus, the neural network between the HPC and mPFC is a promising target for future therapeutic interventions associated with these psychiatric disorders.

Conclusion

Animal and human studies strongly implicate the HPC-mPFC network in cognitive process and emotional regulation associated with psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, and PTSD. Physical or functional disruptions in the HPC-mPFC circuit might be a form of pathophysiology that is common to many psychiatric disorders. Further, study of the physiology and pathophysiology of hippocampal-prefrontal circuits will be essential for developing novel therapeutic interventions for these diseases.

Funding

Supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01MH065961) and a McKnight Memory and Cognitive Disorders Award to SM.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- EC

entorhinal cortex

- HPC

hippocampus

- IL

infralimbic prefrontal cortex

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- NAcc

nucleus accumbens

- PH

parahippocampal cortex

- PL

prelimbic prefrontal cortex

- PRh

perirhinal cortex

- PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder

- RE

nucleus reuniens

- SUB

subiculum

- VH

ventral hippocampus

- vmPFC

ventromedial prefrontal cortex

- VTA

ventral tegmental area.

References

- Abdallah C. G., Jackowski A., Sato J. R., Mao X., Kang G., Cheema R., et al. (2015). Prefrontal cortical GABA abnormalities are associated with reduced hippocampal volume in major depressive disorder. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 25, 1082–1090. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari A., Topiwala M. A., Gordon J. A. (2010). Synchronized activity between the ventral hippocampus and the medial prefrontal cortex during anxiety. Neuron 65, 257–269. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K. L., Rajagovindan R., Ghacibeh G. A., Meador K. J., Ding M. (2010). Theta oscillations mediate interaction between prefrontal cortex and medial temporal lobe in human memory. Cereb. Cortex 20, 1604–1612. 10.1093/cercor/bhp223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A. (2003). Working memory: looking back and looking forward. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 829–839. 10.1038/nrn1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearden C. E., Thompson P. M., Avedissian C., Klunder A. D., Nicoletti M., Dierschke N., et al. (2009). Altered hippocampal morphology in unmedicated patients with major depressive illness. ASN Neuro 1:e00020. 10.1042/an20090026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benchenane K., Peyrache A., Khamassi M., Tierney P. L., Gioanni Y., Battaglia F. P., et al. (2010). Coherent theta oscillations and reorganization of spike timing in the hippocampal-prefrontal network upon learning. Neuron 66, 921–936. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram E. H., Zhang D. X. (1999). Thalamic excitation of hippocampal CA1 neurons: a comparison with the effects of CA3 stimulation. Neuroscience, 92 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss T. V., Collingridge G. L. (1993). A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature 361, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokor H., Csáki A., Kocsis K., Kiss J. (2002). Cellular architecture of the nucleus reuniens thalami and its putative aspartatergic/glutamatergic projection to the hippocampus and medial septum in the rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 16, 1227–1239. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton M. E., Bolles R. C. (1979). Role of conditioned contextual stimuli in reinstatement of extinguished fear. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process 5, 368–378. 10.1037//0097-7403.5.4.368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton M. E., Nelson J. B. (1994). Context-specificity of target versus feature inhibition in a feature-negative discrimination. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process 20, 51–65. 10.1037/e665412011-076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton M. E. (2002). Context, ambiguity and unlearning: sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biol. Psychiatry 52, 976–986. 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01546-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton M. E. (2004). Context and behavioral processes in extinction. Learn. Mem. 11, 485–494. 10.1101/lm.78804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brincat S. L., Miller E. K. (2015). Frequency-specific hippocampal-prefrontal interactions during associative learning. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 576–581. 10.1038/nn.3954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burette F., Jay T. M., Laroche S. (1997). Reversal of LTP in the hippocampal afferent fiber system to the prefrontal cortex in vivo with low-frequency patterns of stimulation that do not produce LTD. J. Neurophysiol. 78, 1155–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton B. G., Hok V., Save E., Poucet B. (2009). Lesion of the ventral and intermediate hippocampus abolishes anticipatory activity in the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Behav. Brain Res. 199, 222–234. 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.11.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. B., Sesack S. R. (1996). Hippocampal afferents to the rat prefrontal cortex: synaptic targets and relation to dopamine terminals. J. Comp. Neurol. 369, 1–15. 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19960520)369:11::aid-cne13.0.co;2-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavada C., Company T., Tejedor J., Cruz-Rizzolo R. J., Reinoso-Suarez F. (2000). The anatomical connections of the macaque monkey orbitofrontal cortex. A review. Cereb. Cortex. 10, 220–242. 10.1093/cercor/10.3.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cenquizca L. A., Swanson L. W. (2007). Spatial organization of direct hippocampal field CA1 axonal projections to the rest of the cerebral cortex. Brain Res. Rev. 56, 1–26. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croxson P. L., Johansen-Berg H., Behrens T. E., Robson M. D., Pinsk M. A., Gross C. G.,, et al. (2005). Quantitative investigation of connections of the prefrontal cortex in the human and macaque using probabilistic diffusion tractography. J. Neurosci. 25, 8854–8866. 10.1523/jneurosci.1311-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchwell J. C., Kesner R. P. (2011). Hippocampal-prefrontal dynamics in spatial working memory: interactions and independent parallel processing. Behav. Brain Res. 225, 389–395. 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.07.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgin L. L. (2011). Oscillations and hippocampal-prefrontal synchrony. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 21, 467–474. 10.1016/j.conb.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davachi L. (2006). Item, context and relational episodic encoding in humans. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16, 693–700. 10.1016/j.conb.2006.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoodi F. G., Motamedi F., Naghdi N., Akbari E. (2009). Effect of reversible inactivation of the reuniens nucleus on spatial learning and memory in rats using Morris water maze task. Behav. Brain Res. 198, 130–135. 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davoodi F. G., Motamedi F., Akbari E., Ghanbarian E., Jila B. (2011). Effect of reversible inactivation of reuniens nucleus on memory processing in passive avoidance task. Behav. Brain Res. 221, 1–6. 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellarocchetta A. I., Milner B. (1993). Strategic search and retrieval inhibition-the role of the frontal lobes. Neuropsychologia 31, 503–524. 10.1016/0028-3932(93)90049-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dégenètais E., Thierry A. M., Glowinski J., Gioanni Y. (2003). Synaptic influence of hippocampus on pyramidal cells of the rat prefrontal cortex: an in vivo intracellular recording study. Cereb. Cortex 13, 782–792. 10.1093/cercor/13.7.782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Prisco G. V., Vertes R. P. (2006). Excitatory actions of the ventral midline thalamus (rhomboid/reuniens) on the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat. Synapse 60, 45–55. 10.1002/syn.20271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diana R. A., Yonelinas A. P., Ranganath C. (2010). Medial temporal lobe activity during source retrieval reflects information type, not memory strength. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 22, 1808–1818. 10.1162/jocn.2009.21335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan R. J., Fletcher P. C. (1997). Dissociating prefrontal and hippocampal function in episodic memory encoding. Nature 388, 582–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolleman-Van der Weel M. J., Da Silva F. L., Witter M. P. (1997). Nucleus reuniens thalami modulates activity in hippocampal field CA1 through excitatory and inhibitory mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 17, 5640–5650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek S. M., Bear M. F. (1992). Homosynaptic long-term depression in area CA1 of hippocampus and effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor blockade. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 89, 4363–4367. 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eacott M. J., Easton A. (2010). Episodic memory in animals: remembering which occasion. Neuropsychologia 48, 2273–2280. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H. (2014). Time cells in the hippocampus: a new dimension for mapping memories. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15, 732–744. 10.1038/nrn3827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenbaum H., Yonelinas A. R., Ranganath C. (2007). The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 30, 123–152. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eleore L., López-Ramos J. C., Guerra-Narbona R., Delgado-García J. M. (2011). Role of reuniens nucleus projections to the medial prefrontal cortex and to the hippocampal pyramidal CA1 area in associative learning. PLoS One 6:e23538. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farovik A., Dupont L. M., Arce M., Eichenbaum H. (2008). Medial prefrontal cortex supports recollection, but not familiarity, in the rat. J. Neurosci. 28, 13428–13434. 10.1523/jneurosci.3662-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco S. B., Seamans J. K., Phillips A. G. (1997). Selective roles for hippocampal, prefrontal cortical and ventral striatal circuits in radial-arm maze tasks with or without a delay. J. Neurosci. 17, 1880–1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouquet C., Tobin C., Rondi-Reig L. (2010). A new approach for modeling episodic memory from rodents to humans: the temporal order memory. Behav. Brain Res. 215, 172–179. 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.05.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia R., Spennato G., Nilsson-Todd L., Moreau J. L., Deschaux O. (2008). Hippocampal low-frequency stimulation and chronic mild stress similarly disrupt fear extinction memory in rats. Neurobiol. Learn Mem. 89, 560–566. 10.1016/j.nlm.2007.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel S. N., Abelson J. L., King A. P., Sripada R. K., Wang X., Gaines L. M., et al. (2014). Impaired contextual modulation of memories in PTSD: an fMRI and psychophysiological study of extinction retention and fear renewal. J. Neurosci. 34, 13435–13443. 10.1523/jneurosci.4287-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genzel L., Dresler M., Cornu M., Jäger E., Konrad B., Adamczyk M., et al. (2015). Medial prefrontal-hippocampal connectivity and motor memory consolidation in depression and schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 77, 177–186. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godsil B. P., Kiss J. P., Spedding M., Jay T. M. (2013). The hippocampal-prefrontal pathway: The weak link in psychiatric disorders? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 23, 1165–1181. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J. A. (2011). Oscillations and hippocampal-prefrontal synchrony. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 21, 486–491. 10.1016/j.conb.2011.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y., Grace A. A. (2005). Dopaminergic modulation of limbic and cortical drive of nucleus accumbens in goal-directed behavior. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 805–812. 10.1038/nn1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto Y., Grace A. A. (2008). Limbic and cortical information processing in the nucleus accumbens. Trends Neurosci. 31, 552–558. 10.1016/j.tins.2008.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin A. L. (2015). Role of the thalamic nucleus reuniens in mediating interactions between the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex during spatial working memory. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 9:29. 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen H. J., Wright C. I., Beijer A. V., Voorn P. (1999). Convergence and segregation of ventral striatal inputs and outputs. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 877, 49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo M. E., Eichenbaum H. (2005). Hippocampal mechanisms for the context-dependent retrieval of episodes. Neural Netw. 18, 1172–1190. 10.1016/j.neunet.2005.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hembrook J. R., Mair R. G. (2011). Lesions of reuniens and rhomboid thalamic nuclei impair radial maze win-shift performance. Hippocampus 21, 815–826. 10.1002/hipo.20797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hembrook J. R., Onos K. D., Mair R. G. (2012). Inactivation of ventral midline thalamus produces selective spatial delayed conditional discrimination impairment in the rat. Hippocampus 22, 853–860. 10.1002/hipo.20945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herry C., Ciocchi S., Senn V., Demmou L., Müller C., Lüthi A. (2008). Switching on and off fear by distinct neuronal circuits. Nature 454, 600–606. 10.1038/nature07166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh R. (1974). The hippocampus and contextual retrieval of information from memory: a theory. Behav. Biol. 12, 421–444. 10.1016/s0091-6773(74)92231-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobin J. A., Ji J., Maren S. (2006). Ventral hippocampal muscimol disrupts context-specific fear memory retrieval after extinction in rats. Hippocampus 16, 174–182. 10.1002/hipo.20144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover W. B., Vertes R. P. (2007). Anatomical analysis of afferent projections to the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Struct. Funct. 212, 149–179. 10.1007/s00429-007-0150-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover W. B., Vertes R. P. (2012). Collateral projections from nucleus reuniens of thalamus to hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex in the rat: a single and double retrograde fluorescent labeling study. Brain Struct. Funct. 217, 191–209. 10.1007/s00429-011-0345-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman J. M., Zilli E. A., Paley A. M., Hasselmo M. E. (2005). Medial prefrontal cortex cells show dynamic modulation with the hippocampal theta rhythm dependent on behavior. Hippocampus 15, 739–749. 10.1002/hipo.20106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman J. M., Zilli E. A., Paley A. M., Hasselmo M. E. (2010). Working memory performance correlates with prefrontal-hippocampal theta interactions but not with prefrontal neuron firing rates. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 4:2. 10.3389/neuro.07.002.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H. T., Zhang S. J., Witter M. P., Moser E. I., Moser M. B. (2015). A prefrontal-thalamo-hippocampal circuit for goal-directed spatial navigation. Nature 522, 50–55. 10.1038/nature14396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay T. M., Witter M. P. (1991). Distribution of hippocampal CA1 and subicular efferents in the prefrontal cortex of the rat studied by means of anterograde transport of Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin. J. Comp. Neurol. 313, 574–586. 10.1002/cne.903130404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay T. M., Glowinski J., Thierry A. M. (1989). Selectivity of the hippocampal projection to the prelimbic area of the prefrontal cortex in the rat. Brain Res. 505, 337–340. 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91464-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay T. M., Thierry A. M., Wiklund L., Glowinski J. (1992). Excitatory Amino Acid Pathway from the Hippocampus to the Prefrontal Cortex. Contribution of AMPA Receptors in Hippocampo-prefrontal Cortex Transmission. Eur. J. Neurosci. 4, 1285–1295. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00154.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay T. M., Burette F., Laroche S. (1995). NMDA Receptor-dependent Long-term Potentiation in the Hippocampal Afferent Fibre System to the Prefrontal Cortex in the Rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 7, 247–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay T. M., Burette F., Laroche S. (1996). Plasticity of the hippocampal-prefrontal cortex synapses. J. Physiol. Paris 90, 361–366. 10.1016/s0928-4257(97)87920-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay T. M., Gurden H., Yamaguchi T. (1998). Rapid increase in PKA activity during long-term potentiation in the hippocampal afferent fibre system to the prefrontal cortex in vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 10, 3302–3306. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J., Maren S. (2015). Fear renewal preferentially activates ventral hippocampal neurons projecting to both amygdala and prefrontal cortex in rats. Sci. Rep. 5:8388. 10.1038/srep08388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. W., Wilson M. A. (2005). Theta rhythms coordinate hippocampal-prefrontal interactions in a spatial memory task. PLoS biol. 3, e402. 10.3410/f.1029541.346578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch R., Korenfeld E., Stephan K. E., Weiskopf N., Seymour B., Dolan R. J. (2006). Context-dependent human extinction memory is mediated by a ventromedial prefrontal and hippocampal network. J. Neurosci. 26, 9503–9511. 10.1523/jneurosci.2021-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy P. J., Shapiro M. L. (2004). Retrieving memories via internal context requires the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 24, 6979–6985. 10.1523/jneurosci.1388-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapska E., Maren S. (2009). Reciprocal patterns of c-Fos expression in the medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala after extinction and renewal of conditioned fear. Learn. Mem. 16, 486–493. 10.1101/lm.1463909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapska E., Macias M., Mikosz M., Nowak A., Owczarek D., Wawrzyniak M., et al. (2012). Functional anatomy of neural circuits regulating fear and extinction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 109, 17093–17098. 10.1073/pnas.1202087109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komorowski R. W., Manns J. R., Eichenbaum H. (2009). Robust conjunctive item-place coding by hippocampal neurons parallels learning what happens where. J. Neurosci. 29, 9918–9929. 10.1523/jneurosci.1378-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyd R. J., Bilkey D. K. (2003). Prefrontal cortex lesions modify the spatial properties of hippocampal place cells. Cereb. Cortex 13, 444–451. 10.1093/cercor/13.5.444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche S., Jay T. M., Thierry A. M. (1990). Long-term potentiation in the prefrontal cortex following stimulation of the hippocampal CA1/subicular region. Neurosci. Lett. 114, 184–190. 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90069-l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche S., Davis S., Jay T. M. (2000). Plasticity at hippocampal to prefrontal cortex synapses: dual roles in working memory and consolidation. Hippocampus 10, 438–446. 10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:4438::aid-hipo103.3.co;2-v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lett T. A., Voineskos A. N., Kennedy J. L., Levine B., Daskalakis Z. J. (2014). Treating working memory deficits in schizophrenia: a review of the neurobiology. Biol. Psychiatry 75, 361–370. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon I., Sripada C. S. (2007). The functional neuroanatomy of PTSD: a critical review. Prog. Brain Res. 167, 151–169. 10.1016/s0079-6123(07)67011-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S. (2011). Seeking a spotless mind: extinction, deconsolidation and erasure of fear memory. Neuron 70, 830–845. 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S., Holmes A. (2015). Stress and fear extinction. Neuropsychopharmacology. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1038/npp.2015.180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S., Holt W. (2000). The hippocampus and contextual memory retrieval in Pavlovian conditioning. Behav. Brain Res. 110, 97–108. 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00188-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S., Quirk G. J. (2004). Neuronal signalling of fear memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 844–852. 10.1038/nrn1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S., Phan K. L., Liberzon I. (2013). The contextual brain: implications for fear conditioning, extinction and psychopathology. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 417–428. 10.1038/nrn3492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna J. T., Vertes R. P. (2004). Afferent projections to nucleus reuniens of the thalamus. J. Comp. Neurol. 480, 115–142. 10.1002/cne.20342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A. S., Olsen R. K., Kohn P. D., Brown T., Egan M. F., Weinberger D. R., et al. (2005). Regionally specific disturbance of dorsolateral prefrontal-hippocampal functional connectivity in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 379–386. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad M. R., Wright C. I., Orr S. P., Pitman R. K., Quirk G. J., Rauch S. L. (2007). Recall of fear extinction in humans activates the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in concert. Biol. Psychiatry. 62, 446–454. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navawongse R., Eichenbaum H. (2013). Distinct pathways for rule-based retrieval and spatial mapping of memory representations in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 33, 1002–1013. 10.1523/jneurosci.3891-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini C. A., Maren S. (2012). Neural and cellular mechanisms of fear and extinction memory formation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36, 1773–1802. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini C. A., Kim J. H., Knapska E., Maren S. (2011). Hippocampal and prefrontal projections to the basal amygdala mediate contextual regulation of fear after extinction. J. Neurosci. 31, 17269–17277. 10.1523/jneurosci.4095-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J., Dieppa-Perea L. M., Melendez L. M., Quirk G. J. (2010). Induction of fear extinction with hippocampal-infralimbic BDNF. Science 328, 1288–1290. 10.1126/science.1186909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter M. C., Burk J. A., Mair R. G. (2000). A comparison of the effects of hippocampal or prefrontal cortical lesions on three versions of delayed non-matching-to-sample based on positional or spatial cues. Behav. Brain Res. 109, 69–81. 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00161-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston A. R., Eichenbaum H. (2013). Interplay of hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in memory. Curr. Biol. 23, R764–R773. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C. (2010). A unified framework for the functional organization of the medial temporal lobes and the phenomenology of episodic memory. Hippocampus 20, 1263–1290. 10.1002/hipo.20852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusson A. M., Charney D. S. (1997). Animal models of relevance to PTSD. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 821, 332–351. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Vidal L. E., Do-Monte F. H., Sotres-Bayon F., Quirk G. J. (2014). Hippocampal-prefrontal BDNF and memory for fear extinction. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 2161–2169. 10.1038/npp.2014.64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo S. J., Nestler E. J. (2013). The brain reward circuitry in mood disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 609–625. 10.1038/nrn3381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacter D. L., Harbluk J. L., McLachlan D. R. (1984). Retrieval without recollection: An experimental analysis of source amnesia. J. Verbal Learning Verbal Behav. 23, 593–611. 10.1016/s0022-5371(84)90373-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld T. J., Kloth A. D., Hsueh B., Runkle M. B., Kane G. A., Wang S. S. H., et al. (2014). Gap junctions in the ventral hippocampal-medial prefrontal pathway are involved in anxiety regulation. J. Neurosci. 34, 15679–15688. 10.1523/jneurosci.3234-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura A. P., Jurica P. J., Mangels J. A., Gershberg F. B., Knight R. T. (1995). Susceptibility to memory interference effects following frontal lobe damage: Findings from tests of paired-associate learning. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 7, 144–152. 10.1162/jocn.1995.7.2.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura A. P., Janowsky J. S., Squire L. R. (1990). Memory for the temporal order of events in patients with frontal lobe lesions and amnesic patients. Neuropsychologia 28, 803–813. 10.1016/0028-3932(90)90004-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siapas A. G., Lubenov E. V., Wilson M. A. (2005). Prefrontal phase locking to hippocampal theta oscillations. Neuron 46, 141–151. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdsson T., Stark K. L., Karayiorgou M., Gogos J. A., Gordon J. A. (2010). Impaired hippocampal-prefrontal synchrony in a genetic mouse model of schizophrenia. Nature 464, 763–767. 10.1038/nature08855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons J. S., Verfaellie M., Galton C. J., Miller B. L., Hodges J. R., Graham K. S. (2002). Recollection-based memory in frontotemporal dementia: implications for theories of long-term memory. Brain 125, 2523–2536. 10.1093/brain/awf247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons J. S., Spiers H. J. (2003). Prefrontal and medial temporal lobe interactions in long-term memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4, 637–648. 10.1038/nrn1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotres-Bayon F., Sierra-Mercado D., Pardilla-Delgado E., Quirk G. J. (2012). Gating of fear in prelimbic cortex by hippocampal and amygdala inputs. Neuron 76, 804–812. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellman T., Rigotti M., Ahmari S. E., Fusi S., Gogos J. A., Gordon J. A. (2015). Hippocampal-prefrontal input supports spatial encoding in working memory. Nature 522, 309–314. 10.1038/nature14445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford J. M., Raybuck J. D., Ryabinin A. E., Lattal K. M. (2012). Increasing histone acetylation in the hippocampus-infralimbic network enhances fear extinction. Biol. Psychiatry 72, 25–33. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield C., Mangels J. A. (2005). Coherent theta-band EEG activity predicts item-context binding during encoding. Neuroimage 24, 692–703. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson L. W., Kohler C. (1986). Anatomical evidence for direct projections from the entorhinal area to the entire cortical mantle in the rat. J. Neurosci. 6, 3010–3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swick D., Knight R. T. (1999). Contributions of prefrontal cortex to recognition memory: electrophysiological and behavioral evidence. Neuropsychology 13, 155–170. 10.1037//0894-4105.13.2.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takita M., Izaki Y., Jay T. M., Kaneko H., Suzuki S. S. (1999). Induction of stable long-term depression in vivo in the hippocampal-prefrontal cortex pathway. Eur. J. Neurosci. 11, 4145–4148. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00870.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierry A. M., Gioanni Y., Dégénétais E., Glowinski J. (2000). Hippocampo-prefrontal cortex pathway: anatomical and electrophysiological characteristics. Hippocampus 10, 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney P. L., Dégenetais E., Thierry A. M., Glowinski J., Gioanni Y. (2004). Influence of the hippocampus on interneurons of the rat prefrontal cortex. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 514–524. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03501.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E. (1983). Elements of Episodic Memory. USA: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E., Thomson D. M. (1973). Encoding specificity and retrieval processes in episodic memory. Psychol. Rev. 80, 352–373. 10.1037/h0020071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varela C., Kumar S., Yang J. Y., Wilson M. A. (2014). Anatomical substrates for direct interactions between hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex and the thalamic nucleus reuniens. Brain Struct. Funct. 219, 911–929. 10.1007/s00429-013-0543-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes R. P. (2004). Differential projections of the infralimbic and prelimbic cortex in the rat. Synapse 51, 32–58. 10.1002/syn.10279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervliet B., Baeyens F., Van den Bergh O., Hermans D. (2013). Extinction, generalization and return of fear: a critical review of renewal research in humans. Biol. Psychol. 92, 51–58. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall P. M., Messier C. (2001). The hippocampal formation-orbitomedial prefrontal cortex circuit in the attentional control of active memory. Behav. Brain Res. 127, 99–117. 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00355-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S., Rappelsberger P. (2000). Long-range EEG synchronization during word encoding correlates with successful memory performance. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 9, 299–312. 10.1016/s0926-6410(00)00011-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss S., Müller H. M., Rappelsberger P. (2000). Theta synchronization predicts efficient memory encoding of concrete and abstract nouns. Neuroreport 11, 2357–2361. 10.1097/00001756-200008030-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M., Alcaraz F., Marchand A. R., Coutureau E. (2014). Functional heterogeneity of the limbic thalamus: From hippocampal to cortical functions. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 54, 120–130. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Südhof T. C. (2013). A neural circuit for memory specificity and generalization. Science 339, 1290–1295. 10.1126/science.1229534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y. M., Yukie M., Rockland K. S. (2006). Distinctive morphology of hippocampal CA1 terminations in orbital and medial frontal cortex in macaque monkeys. Exp. Brain Res. 169, 549–553. 10.1007/s00221-005-0187-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Shu N., Liu Y., Song M., Hao Y., Liu H., et al. (2008). Altered resting-state functional connectivity and anatomical connectivity of hippocampus in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 100, 120–132. 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]