Abstract

Giant cell granuloma is a rare benign granulomatous lesion of the bone. The local aggressiveness, potentiation with trauma and complex anatomy of the skull base makes the surgical management in this location challenging. We report a series of three cases along with the clinical presentation, radiological and histopathological findings and the management issues while dealing with this lesion. A review of literature reveals the rarity of the lesion, alternate management modalities and the outcomes for such lesion involving the jaw bones and the skull base. For best outcomes differential diagnosis from giant cell tumor and brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism is essential. Further it may be concluded that there is a need for maximal surgical excision to avoid recurrence as the second line management options are not as effective.

Keywords: Giant cell granuloma, Granulomatous lesion of bone, Paranasal sinus, Skull base

Introduction

Giant Cell Granuloma (GCG) is a benign, non-neoplastic yet locally aggressive, granulomatous lesion of bone probably occurring as an inflammatory response to intraosseous hemorrhage.

It is a rare lesion of the head and neck region (0.00011 % incidence [1]) and most commonly involves the maxilla and mandible in children and young adults, with a slight female predilection. In patients aged 20–40 years, the skull base is the most common cranial site involved.

First introduced by Jaffe in 1953 as a nonneoplastic reactive process, Giant Cell Granuloma is defined [2] by the World Health Organization as an intraosseous lesion consisting of cellular fibrous tissue containing multiple foci of haemorrhage, aggregations of multinucleated giant cells, and occasionally, trabeculae of woven bone.

Differentiation from Giant Cell Tumor (GCT) and Brown Tumor of Hyperparathyroidism though difficult is essential for management and prognosis.

Complete surgical excision is the treatment modality of choice for giant cell granulomas. Other options reported for gnathic lesions [3] include curettage, megavoltage radiotherapy, intralesional steroids, calcitonin and interferon therapy.

In our case series, we aim to highlight the patient profile, radiological features and surgical outcomes of 3 cases of GCG of the paranasal sinuses presenting to us between July and December 2013.

Case Reports

See Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient profile

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 06 years/female | 10 years/male | 30 years/male | |

| Presenting features | Painful swelling over the right maxillary region with right nasal obstruction for 4 months | Bleeding from nose with proptosis of right eye and blurring of vision for 2 months | Generalised headache, Right side nasal obstruction and bleeding, pain on mouth opening, loss of vision, Rt eye-3 months, Lt eye-1 month |

| Clinical evaluation | Swelling of the maxilla extending from orbital floor to the upper alveolus and from malar eminence to lateral nasal wall Endoscopy revealed a mass arising from the lateral nasal wall reaching up to nasal septum |

A firm swelling in the region of right medial canthus and Rt eyeball pushed laterally Rt eye: V/A—6/60, Sluggish reacting semidilated pupil, disc hyperemia with retinal oedema Mass on nasal endoscopy in region of right middle meatus |

Nasal endoscopy showed a mass in right sphenoethmoidal recess, lateral nasal wall near posterior end of middle turbinate and reaching posterior choana B/L Absent perception of light, semidilated non reacting pupils and optic atrophy. Range of eye movements was normal |

| Surgery | Biopsy via Caldwell luc approach Total resection via midfacial degloving preserving the floor of orbit, posterolateral wall of maxilla and hard palate |

Biopsy and Subtotal resection via lateral rhinotomy Total resection via midfacial degloving approach Dura in region of planum sphenoidale and periorbita on both sides preserved |

Biopsy and excision of the nasal part via a midfacial degloving approach Bifrontal craniotomy and a subfrontal approach for the intracranial part of lesion |

| Radiology | Extent of lesion | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 06 years/female | 10 years/male | 30 years/male | |

| CECT | |||

| A heterogeneously enhancing well defined mass of the paranasal sinus causing bony remodeling of all the walls with thinned out cortical bone. Areas of new bone formation seen dispersed within the lesion | Lesion occupying the entire maxillary sinus with thinned out anterolateral and posterolateral walls, causing bulge in the floor of orbit, lateral nasal wall and right half of hard palate. Cortical bone erosion in right malar region | Lesion involving B/L posterior ethmoids, right anterior ethmoids and middle meatus and sphenoid sinus with thinning of B/L lamina papyracea. Intracranial, extradural extension through the planum sphenoidale | Lesion involving B/L posterior ethmoids extending to right pterygopalatine fossa and posterior choana, sphenoid sinus with intracranial, extradural involvement in suprasellar and prepontine cisterns. Right parasellar extension encasing the right internal carotid artery and extension into B/L optic canal present |

| MRI with contrast | |||

| A heterogeneously enhancing iso to hypointense mass, either completely solid or with cystic spaces. Areas of internal septatations present. No evidence of frank intradural, intraorbital or infratemporal fossa extension | |||

All 3 patients had normal routine blood investigations. Besides these, S. Calcium, Alkaline Phosphatase & Parathormone levels were also within normal limits.

Representative Radiology (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4)

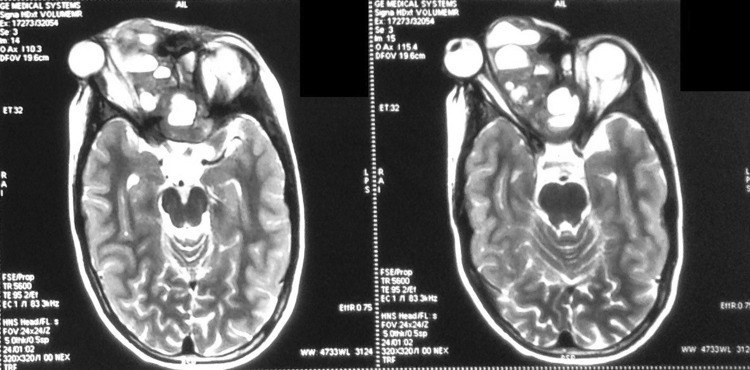

Fig. 1.

Case 2—coronal T2W MRI sequences on Initial presentation

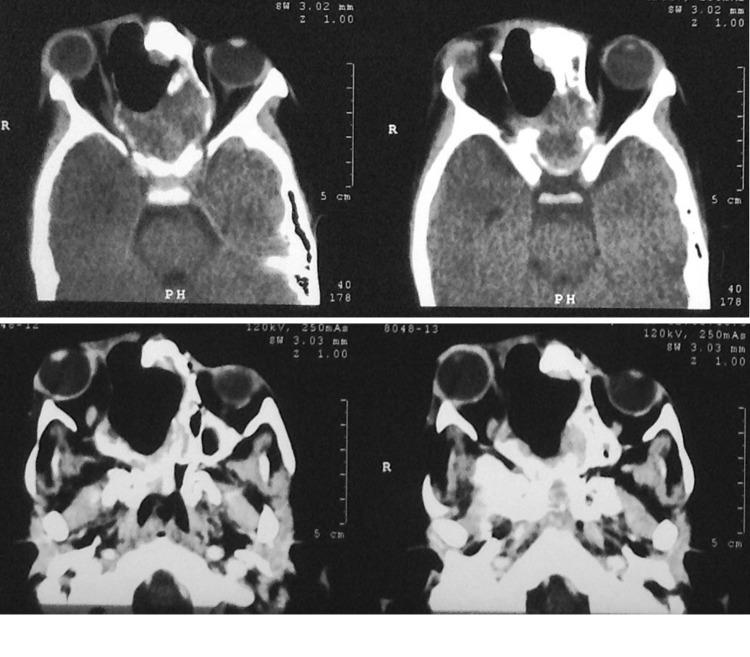

Fig. 2.

Case 2—post op CT after subtotal excision via lateral rhinotomy

Fig. 3.

Case 2—sagittal and Coronal CT scan 1 month post op showing regrowth of lesion

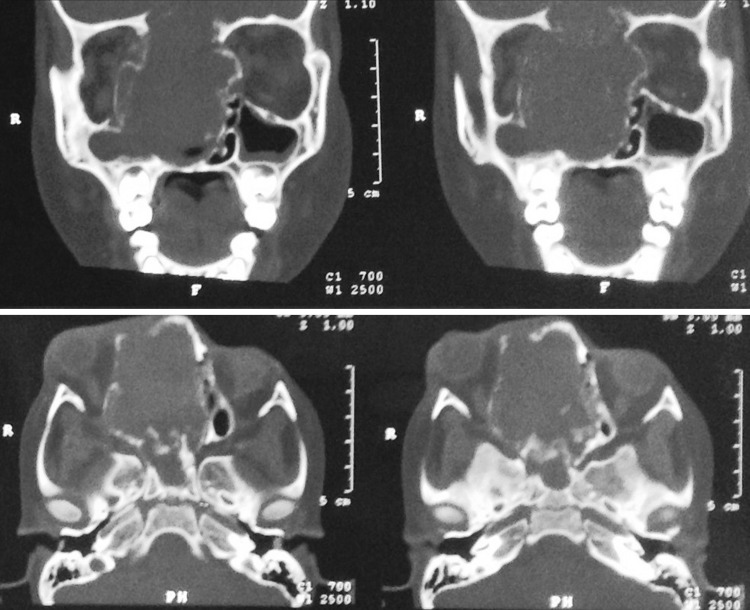

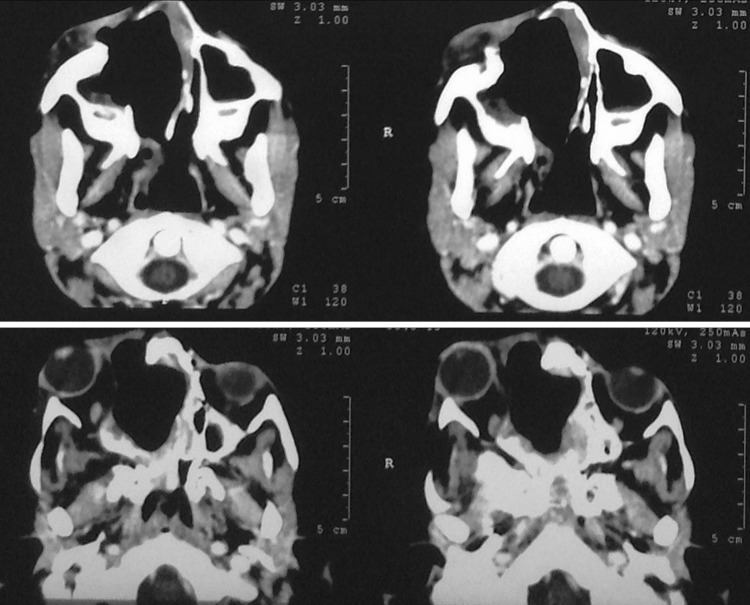

Fig. 4.

Case 2—coronal CT scan 6 months after final surgery showing no evidence of residue/recurrence of lesion

Histopathology

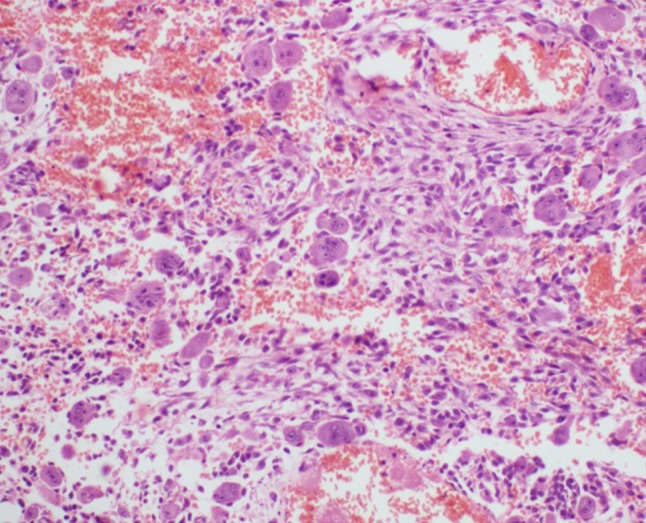

The specimen from all the three cases showed similar histology comprising of proliferation of fibroblastic spindle cells arranged in short interlacing fascicles along with non-uniform distribution of osteoclastic giant cells, areas of sclerosis, hemorrhage and few hemosiderin laden macrophages. No necrosis or mitosis was seen (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

High power microphotograph showing spindle shaped fibroblasts with multinucleated giant cells and interspersed areas of hemorrhage (H&E stain, ×400 magnification)

Patient Outcome

See Table 2.

Table 2.

Outcome of surgery & current status

| Outcome of surgery and current status | ||

|---|---|---|

| 06 years/female | 10 years/male | 30 years/male |

| (Rt. maxillary sinus lesion) | (ethmoid sinus lesion) | (sphenoid sinus lesion) |

| Swelling of the right maxillary region resolved after surgery At present, the patient is under regular follow up for past 15 months and there is no endoscopic/radiological evidence of recurrence (post op 6 months CT) |

Swelling in region of medial canthus and floor of orbit on right side reduced significantly immediately following surgery along with a marked reduction in proptosis. Rt eye vision improved to 6/18 at 1 month At present, the patient is under regular follow up of 12 months with no endoscopic/radiological evidence of recurrence (post op 6 months CT) |

Headache, nasal obstruction and pain on mouth opening were relieved after surgery Lesion encasing the right internal carotid artery and extending into the optic canals were not addressed surgically. 2 months follow up scan again revealed presence of mass in the ethmoids, sphenoid with suprasellar and intraorbital extension The lesion stabilized following External Beam Radiotherapy of 40 Gy given in 20 fractions |

| No added ophthalmological or neurological deficits were found in any of the patients post operatively. The visual acuity of the last patient did not improve | ||

Discussion

Giant cell granulomas are rare lesions of the paranasal sinuses. Though reported to be a consequence of trauma/haemorrhage [4] (secondary to inflammation), the exact cause remains obscure. Flare up and recurrence during pregnancy suggest a possible hormonal dependence [5]. In the cases presenting to us a rapid increase in size was seen following biopsy or subtotal excision.

Genetic abnormalities may be indicated. The lesion may be associated with conditions like Neurofibromatosis-1 or Noonan syndrome [6].

It is believed that the spindle (fibroblast/fibroblast like) cell is the inducing cell and the giant cell causes the features of GCG. Overexpression of the cell cycle protein Ki-67 and of MDM2 protein/gene has been documented in GCG [7]. The multinucleated giant cells of GCG are strongly immunoreactive for CD68, suggesting histiocyte or macrophage origin from mesenchyme of marrow.

Reported symptoms are non-specific (soft tissue swelling/pain) and related to the site involved. Manifestation as a slowly growing mass often leads to a delay in diagnosis.

Radiological findings [8] on CT and MRI are non-specific and mimic a fibroosseous vascular lesion.

Histopathologically, the lesion shows multinucleated giant cells (evenly distributed or in clusters) and fibroblasts in a stroma containing various amounts of collagen [9]. RBCs are usually evident, although capillaries are small and inconspicuous. Foci of osteoid may be present, particularly around the peripheral margins of the lesion.

Giant cell tumor, Brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism, Aneurysmal bone cyst and Fibrous dysplasia mimic the features of Giant cell granuloma.

Giant cell tumors can be differentiated on histology by presence of larger giant cells with more nuclei and a homogenous distribution compared to GCG. Brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism cannot be ruled out on histopathology. It presents with clinical features of hyperparathyroidism along with characteristic biochemical parameters i.e. elevated S. Calcium, Alkaline Phosphatase and PTH levels with low S. Phosphorus. Aneurysmal Bone Cyst shows presence of sinusoidal blood spaces within the tumor mass on histopathology. Fibrous dysplasia shows only limited foci of giant cells and merges imperceptibly with the surrounding cortical bone and growth normally ceases with maturity.

Histopathology as well as radiological and biochemical evaluation of our patients were consistent with a diagnosis of giant cell granuloma.

The treatment of choice for GCG is complete surgical excision. Following complete surgical excision, the recurrence rates reported have been low around 10–15 % [10]. For extensive skull base lesions which do not lend themselves to complete excision, long term remission have been reported with radical resection of accessible lesion combined with radiotherapy. Risk of sarcomatous transformation following currently used megavoltage radiotherapy is low compared to orthovoltage radiation.

The basic flaw with reported adjuvant treatment modalities like intralesional steroids, calcitonin therapy and use of interferon 2a is that none target the fibroblast cell considered to be the etiological agent in the pathogenesis of GCG.

To the best of our knowledge, there are very few case series larger than individual case reports addressing giant cell granuloma of the paranasal sinuses.

Conclusion

Giant cell granuloma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a child or a young adult with an expansile vascular lesion within any paranasal sinuses with or without cortical breach and isointensity with gray matter typical of a fibrous lesion.

On surgery, these lesions are highly vascular and adherent to surrounding soft tissues and bone. The complex anatomy of the anterior skull base and the vital structures in its vicinity make the management all the more challenging. This is compounded by the tendency of this lesion to increase in size exponentially following surgical trauma and incomplete excision.

Radiotherapy following radical resection is recommended if total excision cannot be achieved. The scope of radiotherapy is however limited by the presence of important neuronal structures in the vicinity of the skull base. Successful use of other second line treatment modalities for such lesions of the skull base has not been reported.

To conclude, complete surgical excision whenever possible, either at the time of biopsy using frozen section or at the earliest following histopathologic confirmation, is essential to achieve favorable outcomes when dealing with these aggressive lesions.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Saurin R. Shah, Email: dr.saurinrshah@gmail.com

Amit Keshri, Email: amitkeshri2000@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.de Lange J, Van Akker HP, Klip H. Incidence and disease-free survival after surgical therapy of central giant cell granulomas of the jaw in The Netherlands: 1990–1995. Head Neck. 2004;26:792–795. doi: 10.1002/hed.20069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kramer IRH, Pindborg JJ, Shear M, editors. Histological typing of odontogenic tumours. 2. Berlin: Springer; 1991. p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chattha MR, Ali K, Aslam A, Afzai B. Current concepts in central giant cell granuloma. PODJ. 2006;26(1):71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiatrak BJ, Gluckmann JL, Fabian RL, Wesseler TA. Giant cell reparative granuloma of the ethmoid sinus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;97:504–509. doi: 10.1177/019459988709700514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fechner RE, Fitz-Hugh GS, Pope TL., Jr Extraordinary growth of giant cell reparative granuloma during pregnancy. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984;110:116–119. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1984.00800280050015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen MM, Jr, Gorlin RJ. Noonan-like/multiple giant cell lesion syndrome. Am J Med Gen. 1991;40:159–166. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320400208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Souza PE, Paim JF, Carvalhais JN. Immunohistochemical expression of p53, MDM2, Ki-67 and PCNA in central giant cell granuloma and giant cell tumor. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999;28:54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1999.tb01996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nackos JS, Wiggins RH, Harnsberger HR. CT and MR imaging of giant cell granuloma of craniofacial bones. Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:1651–1653. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Regezi JA, Pogrel MA. Comments on the pathogenesis and medical treatment of central giant cell granulomas (letter) J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:116–118. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arda HN, Karakus MF, Ozcan M. Giant cell reparative granuloma originating in the ethmoid sinus. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;67(1):83–87. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(02)00348-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]