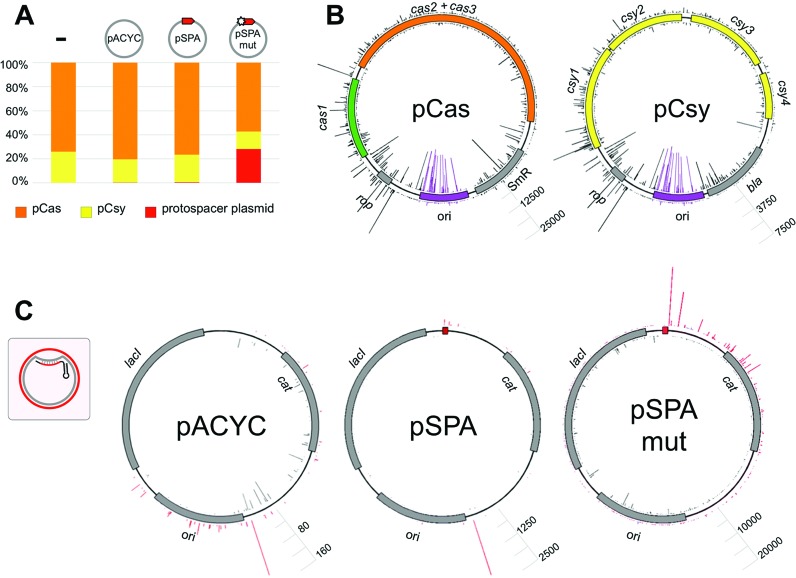

Figure 5.

The origin and distribution of spacers acquired by the P. aeruginosa CRISPR–Cas system. DNA fragments corresponding to expanded CRISPR cassettes shown in Figure 2A (lanes 1–3) and Figure 2B lane 1 were subjected to Illumina sequencing. Spacer sequences were extracted from filtered reads and mapped back to their origin. (A) Bar graph showing the origin of plasmid-derived spacers. Spacers originating from pCas are shown in orange, pCsy – in yellow, and pSPA, pSPAmut or pACYC – in red. (B) Mapping of spacers acquired by cells containing pCas and pCsy on donor plasmids. The cas genes are shown in green and orange, csy genes in yellow, antibiotic resistance and repressor of primer (rop) genes in gray, replication origins – in purple. The heights of gray and purple bars indicate the efficiency (number of times) of spacer from this position was observed. Bars protruding inside and outside of plasmid circles represent spacers derived from different strands of DNA. The height of bars corresponding to most frequently acquired protospacers in both plasmids is made the same for easier comparisons. Scale bars allow to access spacer acquisition efficiencies for each plasmid (number of reads). Purple bars indicate spacers originating from ori regions. Grey bars indicate spacers originating from the rest of each plasmid. (C) Mapping of spacers acquired from pSPA, pSPAmut, or pACYC vector control in cells expressing the cas and csy genes. Where present, a protospacer matching crRNA is shown as a small red box. The inset schematically shows the structure of the R-loop formed by crRNA. Targeted strand is shown in gray, non-targeted – in red. Bars showing spacers originating from each of these strands are colored accordingly. Scale bars indicate spacer acquisition efficiency for each plasmid (number of reads).