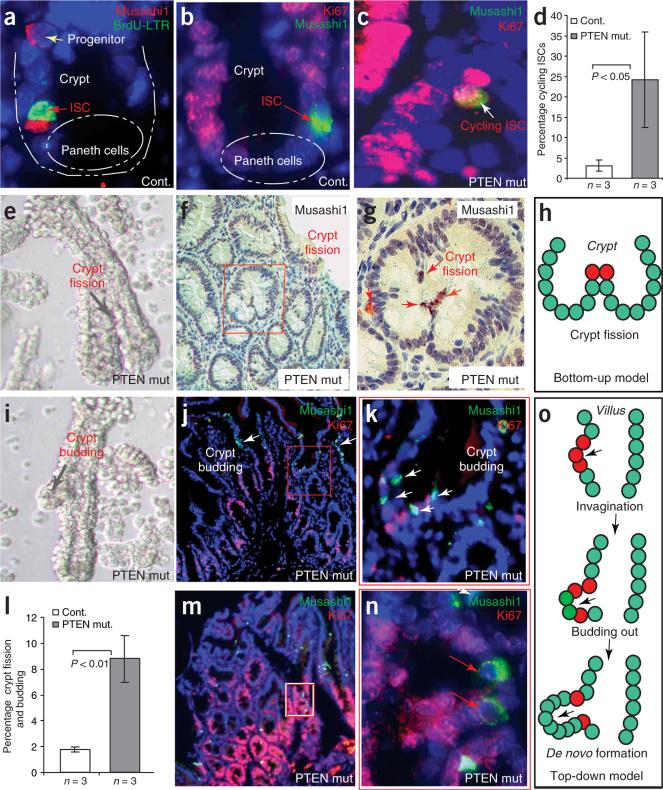

Figure 3.

PTEN-deficient intestinal stem cells were found at the initiation of crypt budding and fission. (a) Association of Musashi1 (red), with BrdU (BrdU-LTR; green) cells in control mice. (b) In control mice, ISCs, identified as Musashi1+ (green) are in most cases Ki67− and therefore slow cycling. (c,d) The percentage of double-positive (Musashi1+ Ki67+) cells was higher in PTEN-deficient intestine. (e) Microdissected crypt showing crypt fission in the PTEN-deficient intestine. (f,g) M+ISC/p cells are detected in the apex of bifurcated fission crypts. Boxed area in f is shown at higher magnification in g. (h) A schematic showing the relationship between M+ISC/p cells (red) and crypt fission. (i) Microdissected crypt showing crypt budding in the PTEN-deficient intestine. (j,k) M+ISC/p cells found at the initiation point of crypt budding or de novo crypt formation. White arrows indicate clusters of M+ISC/p cells detected in a region undergoing invagination (j) and budding (k). The boxed area in j shows a newly formed crypt (shown at higher magnification in k). (l) Graph showing increased percentage of crypt fission and budding in the PTEN mutants. (m,n) Increase in M+ISC/p cells in the polyp region (M) and duplicate M+ISC/p cells in the newly formed crypt (n). The majority of M+ISC/p cells in the polyp region are Ki67− (n). Boxed area in m is shown at higher magnification in n. (o) Model of involvement of M+ISC/p cells (red) in de novo crypt formation in the PTEN-deficient polyp region.