Abstract

Individuals with low distress tolerance (DT) experience negative emotion as particularly threatening and are highly motivated to reduce or avoid such affective experiences. Consequently, these individuals have difficulty regulating emotions and tend to engage in maladaptive strategies, such as overeating, as a means to reduce or avoid distress. Hatha yoga encourages one to implement present-centered awareness and non-reaction in the face of physical and psychological discomfort and, thus, emerges as a potential strategy for increasing DT. To test whether a hatha yoga intervention can enhance DT, a transdiagnostic risk and maintenance factor, this study randomly assigned females high in emotional eating in response to stress (N = 52) either to an 8-week, twice-weekly hatha (Bikram) yoga intervention or to a waitlist control condition. Self-reported DT and emotional eating were measured at baseline, weekly during treatment, and 1-week post-treatment. Consistent with prediction, participants in the yoga condition reported greater increases in DT over the course of the intervention relative to waitlist participants (Cohen’s d = .82). Also consistent with prediction, the reduction in emotional eating was greater for the yoga condition than the waitlist condition (Cohen’s d = .92). Importantly, reductions distress absorption, a specific sub-facet of DT, accounted for 15% of the variance in emotional eating, a hallmark behavior of eating pathology and risk factor for obesity.

Keywords: Hatha Yoga, Distress Tolerance, Intervention, Exercise

Individuals with low distress or affective tolerance experience negative emotions as particularly threatening and are highly motivated to alter such experiential states (Simons & Gaher, 2005). As a result of their intolerance of distress, these individuals tend to engage in coping strategies that pose mental and physical health risks, such as cigarette smoking (Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, Strong, & Zvolensky, 2005; Buckner, Keough, & Schmidt, 2007; Bujarski, Norberg, & Copeland, 2012), and binge eating and purging (Anestis, Selby, Fink, & Joiner, 2007), as a means to reduce or avoid emotional distress. Accordingly, distress intolerance has been implicated as a transdiagnostic risk and maintenance factor for psychopathology (Zvolensky, Bernstein, & Vujanovic, 2011), particularly in disorders characterized by heightened emotional reactivity and avoidance, such as substance use, anxiety, eating, and personality disorders (Leyro, Zvolensky, & Bernstein, 2010; Zvolensky et al., 2011).

Extant research has conceptualized and approached measurement of affective intolerance in diverse ways and among heterogeneous samples (Bernstein, Zvolensky, Vujanovic, & Moos, 2009; McHugh & Otto, 2012). This has resulted in the emergence of various domain-specific affective intolerance sub-constructs that can be challenging to integrate (Bernstein et al., 2009). For example, “intolerance of uncertainty,” particularly relevant to pathology of generalized anxiety (Dugas, Buhr, & Ladouceur, 2004) and obsessive-compulsive disorders (Holaway, Heimberg, & Coles, 2006; Tolin, Abramowitz, Brigidi, & Foa, 2003), reflects a cognitive-affective intolerance for uncertain outcomes. In comparison, “discomfort intolerance” (DI; Schmidt, Richey, & Fitzpatrick, 2006) and “anxiety sensitivity” (AS; Maller & Reiss, 1992) include aversion to somatic sensations of autonomic arousal, which are cornerstone to panic disorder psychopathology.

Deviating from a specific distress domain in their operationalization of the construct, Simons & Gaher (2005) define “distress tolerance” (DT) by facets involved in the process of managing and regulating subjective emotional distress. These include: (1) one’s general perceived Tolerance of negative or threatening emotions, (2) one’s Appraisal or value judgment about feeling distressed or upset, as well as (3) the resulting Absorption of attention in the distress itself, and (3) the propensity for action aimed at Regulation or reduction of distress (Simons & Gaher, 2005). In support of this conceptualization, scores on the self-report based Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS; Simons & Gaher, 2005) have predicted symptom severity and problem behavior in a range of clinical populations (Anestis et al., 2007; Leyro et al., 2010).

Studies examining the psychometric properties of various affective intolerance assessments also evidence support for the existence of a common, domain-general emotional intolerance construct. For example, a factor analysis (McHugh & Otto, 2012) of different self-report assessments of the construct yielded a single-factor latent structure of affective intolerance captured by the Discomfort Intolerance Scale (Schmidt et al., 2006), Anxiety Sensitivity Index (Reiss, Peterson, Gursky, & McNally, 1986), and DTS (Simons & Gaher, 2005). The authors concluded that these measures likely tap a common underlying core trait of affective intolerance, which is most-directly assessed by the DTS (McHugh & Otto, 2012). Thus, distress tolerance DT, as measured by the DTS, appears to be a good option for investigations examining the relationship of affect intolerance to psychopathology and intervention effects.

Because DT is a pervasive contributor to psychopathology, several existing evidence-based treatments specifically aim to target DT. Promisingly, initial intervention research demonstrates that DT can be enhanced and that increases in DT correspond to improvements in symptom severity (Brown et al., 2008; Leyro et al., 2010). These interventions have typically taken a mindfulness-based and/or exposure-based, cognitive-behavioral approach. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993), for example, is an integrative approach that includes a DT skills training component for reducing emotional reactivity, and it has shown efficacy for treating borderline personality (Linehan, 1993; Linehan, 1987; Neacsiu, Rizvi, & Linehan, 2010), eating pathology (Telch, Stewart, & Linehan, 2001; Telch et al., 2001), and substance use disorders (Dimeff & Linehan, 2008). Brown and colleagues have recently developed a novel, combined mindful acceptance/CBT intervention targeting DT for smoking cessation in adults who have previously failed cessation attempts (Brown et al., 2008). By enhancing resilience to distress during critical early abstinence periods, such as the withdrawal phase, this treatment has shown efficacy for difficult-to-treat smokers (Brown et al., 2013).

The mind-body practice of yoga, which is conceptually akin to the interventions just described, may hold similar promise for enhancing DT. Hatha yoga is a branch of yoga described as “moving meditation,” a physical practice of yoga (Iyengar & Menuhin, 1995). Hatha yoga requires one to focus attention on interoceptive cues and breath (pranayama) during and while transitioning to challenging, potentially uncomfortable physical postures called asanas (Hewitt, 1990; Iyengar & Menuhin, 1995). From the Eastern philosophical tradition of mindfulness, hatha yoga encourages one to implement present-centered awareness, non-reaction, and non-judgmental acceptance of one’s present state despite physical or psychological discomfort. In combination with promotion of mindful awareness and acceptance, hatha yoga, especially when practiced at moderate to vigorous intensities, may promote habituation to distress in low-DT persons. Indeed, exposure-based methods of behavioral therapy, including programmed aerobic exercise interventions, have proved effective for reducing sensitivity to autonomic arousal in anxious populations (Broman-Fulks & Storey, 2008; Smits et al., 2008).

Furthermore, evidence from a number of sources has accumulated for the beneficial effects of yoga on mental health problems, including anxiety (Dunn, 2009; Kirkwood, Rampes, Tuffrey, Richardson, & Pilkington, 2005; Smith, Hancock, Blake-Mortimer, & Eckert, 2007), depression (Shapiro et al., 2007; Uebelacker et al., 2010), disordered eating (Carei, Fyfe-Johnson, Breuner, & Brown, 2010; McIver, O’Halloran, & McGartland, 2009), and psychological distress secondary to medical conditions (Curtis, Osadchuk, & Katz, 2011; Shapiro et al., 2007). Yoga also has received support for reducing perceived stress and enhancing overall well-being in sub-clinical populations (Brisbon & Lowery, 2011; Granath, Ingvarsson, von Thiele, & Lundberg, 2006; Huang, Chien, & Chung, 2013; Smith et al., 2007; Uebelacker et al., 2010).

Despite the promise for improving psychological health in distress-sensitive persons, there have been no published reports of the efficacy of yoga for increasing DT. In addition to the theoretical promise of using yoga to improve DT, the importance of this research is further underscored by the increasing popularity of yoga in Western culture as an alternative approach to stress management and psychological wellbeing (Barnes, Bloom, & Nahin, 2008). Yoga’s positive reputation only enhances its potential to become an acceptable and accessible intervention for many people.

In this paper, we test the hypothesis that practicing hatha yoga can increase DT. This hypothesis was tested using data collected as part of a larger investigation examining the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of a hatha yoga intervention for targeting physiological stress reactivity in women high in affective eating and risk for obesity (Hopkins-DeBoer, Medina, Baird, & Smits, Under review). The parent trial draws rationale for testing its hypothesis from the obesity and eating disorder literatures, which describe emotional or stress-induced eating as a major contributor to clinically diagnosable eating disorders, such as binge eating disorder, as well as to rates of obesity, particularly among females (Adam & Epel, 2007). The need to enhance affective coping capacity in this population provides rationale for the present investigation’s examination of DT as an avenue by which yoga may reduce disordered eating behavior.

Accordingly, under this parent study, we randomized 52 females at risk for eating disorders and obesity to either an 8-week hatha yoga intervention (YOGA) or a waitlist control condition (WL). Self-reported emotional eating and DT were measured at baseline, weekly during treatment, and 1-week post-treatment. Our second aim was to examine increases in DT as a mechanism of change accounting for reduced behavioral symptoms of psychopathology resulting from the yoga intervention. Given the sample recruited for the parent study, we examined increases in DT as a mediator of the intervention effects on emotional eating. We hypothesized that, relative to waitlist participants, those in the yoga condition would report greater increases in DT over the course of the intervention, and that these increases in DT would mediate the effects of yoga on emotional eating.

Method

Participants

Participants included adult females from the Dallas community who reported elevated levels of perceived stress, emotional eating, and dietary restraint. Eligibility criteria included score of ≥ 2.06 on the emotional eating subscale (DEES) of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ; van Strien, Frijters, Bergers, & Defares, 1986), score of ≥ 15 on the Restraint Scale (Polivy, Herman, & Howard, 1988), and elevated perceived stress, as defined by scoring ≥ 0.50 SD above the community mean on the Perceived Stress Questionnaire (Levenstein et al., 1993). Eligibility also required sufficient command of the English language and providing written physician medical clearance to participate in yoga practice.

Exclusion criteria included: having regularly practiced (i.e., once a week or more) yoga or other mind-body practices (e.g., tai chi, meditation) within the last year; a significant change to physical activity pattern in the past 3 months; current severe depression or substance dependence; lifetime history of anorexia nervosa or severe mental illness (i.e., bipolar or psychotic disorder of any type); pregnancy; medical conditions that could be aggravated by yoga; body mass index ≥ 40; cognitive dysfunctions or organic brain syndrome that could interfere with capacity to perform study protocol; receiving inpatient psychiatric hospitalization within the past year; or receiving concurrent psychiatric treatment, including both psychotherapy and psychotropic medication.

Procedures

Participants will be recruited through advertisements in local newspapers and flyers that included a link to a secured online eligibility prescreen survey. Respondents who appeared eligible based on their prescreen will be scheduled for a baseline visit one week prior to the start of the yoga program. During this visit participants will be randomized to one of the two conditions (YOGA or WL) using a computerized random number generator. Participants will then be oriented to the program (depending on condition assignment) and scheduled to come

Those randomized to the yoga condition were asked to attend twice-weekly, 90-minute Bikram yoga-style classes at a local yoga studio. Each session consisted of the same series of 26 hatha yoga postures, two breathing exercises, and two savasanas (i.e., a resting/relaxation posture), in a room heated to 104 degrees Fahrenheit, which aids in safe muscle stretching. We selected this type of yoga because it is considered suitable for practitioners of various physical capabilities and, due to its consistent series of postures, is ideal for a standardized intervention protocol. In addition, the hot temperature would provide an opportunity to learn to become confortable with the bodily sensations associated with heat exposure (i.e., increase tolerance of physical distress). At the end of each week of the intervention period, as well as at post-intervention (week 9), all participants (both those assigned to YOGA and WL) were prompted by email to complete a 15–20 minute online survey containing self-report measures of DT, emotional eating, stress, and mood. Following their completion of the week 9 assessment, WL participants were provided the equivalent 2-month yoga membership at no cost.

Measures

Distress tolerance

The Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS; Simons & Gaher, 2005) is a 15-item self-report scale measuring four facets involved in the expectation of, evaluation of, and reaction to distressing states. In addition to a total DT score, the DTS produces four subscale scores measuring: (1) distress Tolerance (i.e., perceived tolerability and aversiveness of distressing feelings; e.g., “I can’t handle feeling distressed or upset”); (2) Appraisal of distress (i.e., acceptability of having the distress; e.g., “My feelings of distress are not acceptable”); (3) Absorption (i.e., tendency for distress to disrupt attention and interfere with in-the-moment functioning; e.g., “My feelings of distress are so intense that they completely take over”); and (4) Regulation (i.e., the strength of one’s propensity to immediately avoid or attenuate the distress; e.g., “I’ll do anything to avoid feeling distressed or upset”). Participants responded to items on a 5-point Likert-type scale, with ratings ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5). The DTS has exhibited 6-month temporal stability and internal consistency, evidencing good reliability (Simons & Gaher, 2005). Total DTS scores, as well as each of its subscales have demonstrated adequate construct validity (Bernstein et al., 2009; Leyro, Bernstein, Vujanovic, McLeish, & Zvolensky, 2011; Simons & Gaher, 2005). In the present sample, internal consistency (Chronbach’s alpha) for the DTS total score at baseline was 0.87. Alpha coefficient for the DTS subscales, Tolerance, Absorption, Appraisal, and Regulation were .72, .77, .72, and .70, respectively.

Emotional eating

The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ; van Strien, Frijters, Bergers, & Defares, 1986) is a widely used and validated 33-item measure that assesses restrained eating, emotional eating, and eating in response to external cues (van Strien, Frijters, van Staveren, Defares, & Deurenberg, 1986). Each item is rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). The emotional eating scale (DEES) of the DEBQ, which measures tendency to eat in response to negative emotions, was used to screen for emotional eating, with a score ≥ 2.06 indicative of significantly elevated distress-induced eating tendencies. In the present sample, internal consistency (Chronbach’s alpha) for the DEES at baseline was 0.92.

Data Analytic Strategy

In order to analyze changes in self-reported DT and emotional eating assessed over the intervention period, we used mixed effects multilevel modeling (MLM) in SPSS® Version 20, which allows for the analysis of longitudinal data both within and between subjects (S. Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2004; Singer & Willet, 2003). MLM has several advantages over other strategies commonly used to analyze longitudinal data (MacKinnon, 2008; Singer & Willet, 2003; Zhang, Zyphur, & Preacher, 2009). For example, as a form of intent to treat analysis (ITT), MLM allows for the inclusion of subjects with missing data, whereby it is able to estimate a longitudinal change trajectory for each subject using the number of completed assessments available. Additionally, MLM allows for modeling of the error covariance within-subjects, which was modeled as autoregressive [AR(1)] in the present study.

In line with standard guidelines for MLM (Singer & Willet, 2003), we tested a series of 2-level models to measure rates of improvement (Level 1) in self-reported levels of distress tolerance (DTS) and emotional eating (DEES) as a function of study condition (Level 2). Level 1 of the MLM model estimates outcome as a function of time within individual (i.e., Outcomeij = b0i + b1i * Timeij +εij, where i represents each individual subject and j represents each assessment point). Level 2 of the model allows for between-individual characteristics (i.e., study condition [COND], coded “0 = Yoga”, “1 = WL”) to influence outcome. The equations for Level 2 are b0i = 00 + 01*CONDi + u0i, and b1i = 10 + 01*CONDi + u1i. Level 2 is nested into the Level 1 equation, forming a composite 2-level model with the equation, Outcomeij = γ00 + γ10*Time + γ01* COND + γ11* COND *Time + (εij + u0i + u1i*TIME).

In order to determine the most accurate MLM model reflective of changes over time in our main outcomes (DTS, DEES), we compared linear, quadratic, and logarithmic growth curves for each outcome based on their deviance statistics (Bayesian Information Criterion [BIC]). For both DTS and DEES outcomes, the logarithmic growth curve was found to be the best fit to the data. Therefore, the logarithmic transformation of time [ln(Time)] was used in all tests analyzing these measures longitudinally.

Guidelines for estimating power to detect polynomial change using MLM in longitudinal studies have been published by Raudenbush and Xiao-Feng (2001), taking into account study duration, assessment frequency, and sample size. For our purpose of measuring weekly change in our outcomes over a 10-week period, a sample of N ≥ 44 was predicted to be adequate for achieving ≥ 80% power to be able to detect a large effect (S. W. Raudenbush & Xiao-Feng, 2001).

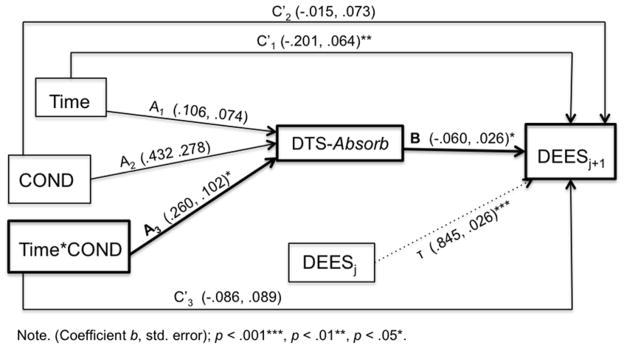

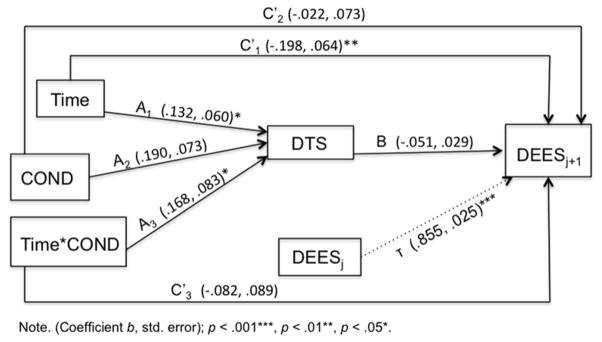

Mediation analyses

Establishing mediation in randomized trials requires demonstrating that the change in the mediator causes a change in the outcome. Enhancing the causal interpretation of our mediation test, we used a multi-level (MLM) cross-lagged panel analysis to test the mediating effect of DTS on subsequent reductions in DEES (Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord, & Kupfer, 2001; Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002). To test the size and significance of the proposed mediator, DTS, we employed MacKinnon and colleagues’ asymmetric distribution of products test (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007; MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Significance of a proposed indirect mediated pathway is determined based on confidence intervals for the product of the indirect paths of coefficients A*B (see Figure 4). If the 95% confidence interval for the A*B product does not include 0, the mediated effect is considered significant (MacKinnon et al., 2004).

Figure 4.

Cross-lagged Mediation Model for DTS-Absorption

The coefficient for the interaction term (i.e., COND*Time effect on DTSj) represents the A Path of our model (labeled A3 in Figure 1, Figure 4). In order to control for temporal order of effects between mediator and outcome using a cross-lagged panel strategy, we lag-transformed the original variable DEES by one time point (DEESj+1). Thus, the B Path of our mediation model represents the coefficient for the effect of DTSj on DEESj+1 controlling for DEESj. (levels of the mediator DTS predicting future levels of the outcome (DEES); see Figure 1, Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Cross-lagged Mediation Model for DTS

Size of the mediated effect

In order to estimate the proportion mediated by the proposed mediator (PM;(Shrout & Bolger, 2002), an effect size was calculated using the formula (A3* B)/C. The PM represents the proportion of the total effect of the hatha yoga intervention on emotional eating (i.e., the C Path) that was mediated by distress tolerance.

Results

Sample Characteristics

We aimed to recruit a sample of women at-risk for obesity due to high levels of emotional/stress-induced eating. Out of 650 individuals who filled out the online prescreen survey of demographics, eating behavior, perceived stress, depression, and body mass index (BMI), 573 did not meet initial eligibility criteria, and 25 declined participation. Seventy-three of the remaining women completed the diagnostic screening visit. Fifty-two eligible women attended the baseline orientation visit, where 27 were randomized to YOGA and 25 to WL.

Our final sample of 52 women (Mage = 33.52, SD = 6.43) had an average BMI within the overweight range at baseline. Prescreen emotional eating (DEES) scores for those randomized were approximately 2 SDs above normative scores for both obese and non-obese women (Ouwens, van Strien, & van der Staak, 2003; van Strien, Frijters, Bergers, et al., 1986; van Strien & Ouwens, 2003). The sample consisted primarily of non-Hispanic White participants (75%, n = 39). Ten (19.2%) of participants identified as Hispanic/Latina. Participants were well-educated and predominantly middle to upper-middle class with 60% reporting an annual household income of below $75,000. All but one participant reported receiving either a college degree or some college, and 100% reported completing high school. See Table 1 for specific baseline descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical and Demographic Characteristics

| Variable | Yoga (N = 27) | Waitlist (N = 25) | Total (N = 52) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age | 31.52 | 5.47 | 35.68 | 6.80 | 33.60 | 6.09 |

| BMI | 28.38 | 4.08 | 26.60 | 5.94 | 27.4 | 5.09 |

| DTS | 3.22 | 0.68 | 3.30 | 0.85 | 3.26 | 0.75 |

| DEES | 3.60 | 0.81 | 3.44 | 0.68 | 3.52 | 0.74 |

The study conditions did not differ at baseline on BMI, race/ethnicity, or annual income, nor were there differences in baseline assessments of DTS or DEES (p’s > .14). Conditions differed by age, with the YOGA group being significantly younger (F(1,50) = 5.96, p = .02). We therefore controlled for age in all analyses. Overall, 17% (n = 9) of our sample dropped out of the intervention (i.e., missed both post-treatment laboratory visit and survey). Seven (26%) YOGA participants dropped out, whereas only two (8%) WL participants dropped out. However, chi-square analyses revealed that attrition did not differ significantly between conditions (χ2 = 2.91, p = .09). Study completers did not differ from the 10 dropouts in baseline levels of BMI, age, or DEES and DTS scores.

Average weekly yoga attendance for the 27 participants randomized to yoga ranged from 0.13 to 3.25 sessions per week (M = 1.56, SD = 0.82). Ten (27%) participants met (n = 3) or exceeded (n = 7) the prescribed two classes per week. On average, yoga participants completed 60% of the 16 prescribed yoga sessions, and sixteen (84%) completed at least 75% (12 of 16 classes) of the intervention.

Hypothesis Testing

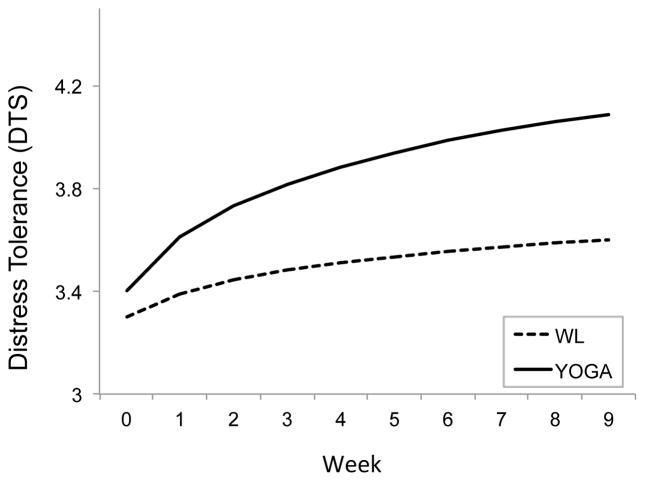

Intervention effects on distress tolerance

As hypothesized, the Condition-by-Time interaction was significant (b = −0.168, t(128) = −2.014, p = 0.046), revealing that the loglinear rate of increase in DT was significantly greater in YOGA than WL (Figure 2). We calculated a Cohen’s d effect size for the between-group effect using the approach recommended by Raudenbush and Xiao-Feng (2001) in multilevel mixed effects models. This yielded a standardized effect size (Cohen’s d) of .82, suggesting that the between-group effect on slope of improvement in DTS was large. This suggests that the average YOGA-treated participant fared better than 79% of those in WL on DT enhancement.

Figure 2.

Changes in Distress Tolerance (DTS) over Time by Condition

Intervention effects on DTS subscales

Additional analyses were conducted to examine between-group differences in the slopes of change for each of the DTS subscales (i.e., Tolerance, Appraisal, Absorption, and/or Regulation). When testing the same model for each of the four subscales, between-group differences were present for Tolerance (b = 0.226, t(149) = 2.154, p = .033; d = .89) and Absorption (b = 0.260, t(136) = 2.544, p = .012; d = .97), but not for Appraisal (b = 0.076, t(139) = 0.977, p = .330) or Regulation (b = 0.107, t(120) = 0.918, p = .361).

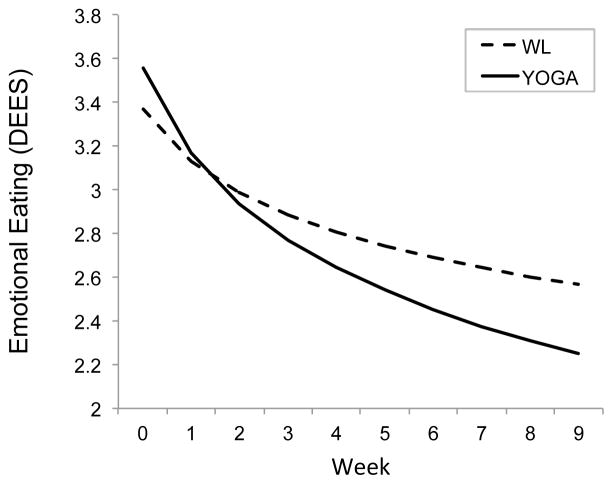

Intervention effects on emotional eating

As hypothesized, there was a significant Condition-by-Time interaction on DEES (b = 0.218, t(104) = 2.519, p = .013), suggesting that the rate of loglinear reduction in emotional eating was greater for YOGA than WL (Figure 3). This effect was large (Cohen’s d = .92), indicating that the average YOGA participant fared better than 82% of those in WL on emotional eating.

Figure 3.

Changes in Emotional Eating (DEES) over Time by Condition

Mediation

The 95% confidence interval for the mediated effect for DTS score was (−.025, .002). Thus, mediation was not supported for the DTS total score (see Figure 1 for A3 and B path coefficients). We replicated these analyses using the DTS subscales. These analyses yielded no mediation for any of the subscales except for DTS-Absorption (95% confidence interval for the mediated effect of (−.07, .01); see Figure 4 for A3 and B path coefficients). Percent of the effect of hatha yoga on emotional eating mediated by DTS-Absorption was 15%.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to test the effects of an 8-week hatha yoga intervention on DT. This investigation was conducted as a secondary aim of its parent trial examining a hatha yoga intervention for physiological stress reactivity and affective eating, a risk factor for disordered eating and obesity. Results showed that, in comparison to a WL control group, an intervention involving twice-weekly hot hatha (Bikram) yoga for 8 weeks resulted in greater improvements in DT (as measured by the DTS) and greater reductions in emotional eating (as measured by the DEES subscale of the DEBQ). Indeed, by week 9 post-intervention assessment, yoga had produced large and clinically meaningful effects, proving to be approximately 80% more effective than WL for improving both DT and emotional eating.

The yoga intervention’s effect on self-reported DT is consistent with results from previous studies showing increases DT resulting from mindfulness and exposure-based behavioral interventions (Baer, 2009; Brown et al., 2008). Our findings for DT suggest potential for yoga interventions to improve affective tolerance in a host of psychological disorders. In addition, our finding that yoga also reduced emotional eating echoes findings from previous studies that provided initial support of yoga in the treatment of eating disorder symptoms (Carei et al., 2010; McIver et al., 2009). Moreover, we expanded on the results of these previous trials by demonstrating yoga’s efficacy for treating subclinical disordered eating problems and related distress, suggesting its clinical utility as a prevention strategy for females at-risk for future obesity and other adverse health effects caused by dysregulated eating patterns.

Our finding that yoga directly enhanced DTS subscales, Tolerance (i.e., meta-cognitions about capacity to handle distress) and Absorption (i.e., attentional interference during distress), suggests that 8 weeks of Bikram yoga practice particularly impacted cognitive components involved in distress processing, rather than those involved in emotional and behavioral distress reactivity (i.e., Appraisal or Regulation). That we found significant between-condition effects over time on these subscales is also consistent with previous studies showing that regular mind-body practice is associated with enhanced capacity to sustain attention while completing a task. One study found that experienced practitioners of yogic meditation performed better on cognitive tasks of attention than non-meditators (Prakash et al., 2010). Another showed that brief mindfulness training beneficially modified attention among alcohol dependent persons with no prevoius background in mindfulness (Garland, Gaylord, Boettiger, & Howard, 2010).

As our second aim, we examined increased DT as a mechanism underlying the effects of yoga on a relevant mental health outcome. namely improvements in emotional eating. Results of the mediation analyses showed that improvements in DTS-Absorption scores mediated the yoga intervention’s positive effect on self-reported emotional eating. Improved Absorption explained 15% of the improvements in emotional eating caused by the yoga intervetnion. Thus, one way yoga reduces emotional eating, at least in this at-risk sample, appears to be by restoring the ability to concentrate and think clearly (i.e., enhanced cognitive capacity) during times of distress. Although yoga reduced DT in general (i.e., DTS total scores), it is intersting that it was only reductions in the Absorption subscale that drove improvements in emotional eating.

We can offer only speculation concerning the mixed findings among DTS subscales, given the paucity of literature providing context in which to interpret our findings. Little empirical attention has been paid to the relative clinical relevance and malleability of the individual DTS subscales in response to intervention (McHugh & Otto, 2012). One possibility is that the DT subfacets change at different times or at different rates in response to intervention. Though our analyses cannot account for this idea, it may be that an 8-week yoga intervention can enhance general self-efficacy for handling distress (i.e., perceived Tolerance), which, in turn, makes the distress less salient in-the-moment, thus improving one’s ability to approach distress with greater cognitive flexibility (i.e., decreased Absorption). Longer interventions and additional follow-up assessments should be used in future research to examine this hyposthesis.

The conjecture that yoga enhances one’s ability to shift attention beyond the sensation of discomfort, toward other stimuli in the immediate environment, is supported by the mindfulness literature (Baer, 2009; Gard et al., 2012; Garland et al., 2010). For example, Garland and colleagues found that a mindfulness intervention for alcohol-dependent participants resulted in improved ability to shift attention away from visual alcohol cues, as well as decreased reliance on thought-supression strategies, a form of experiential avoidance. Although this study lacked a control condition, it provides preliminary support for the use of mindfulness interventions for preventing stress-induced alcohol relapse (Garland et al., 2010). We speculate that ultimately, with greater capacitiy to sustain attention mindfully (i.e., reduced distress absorption), individuals become able to endure or cope healthfully with distress, rather than turning to food to dampen their feelings. Replication and extension of our findings will help more fully explain the relationship between yoga, mindfulness, absorption, and emotional eating.

We would like to note that we only focused on one of several potential psychological therapeutic mechanisms (i.e., DT) in this study, and cannot rule out the possibility that changes in DT are merely a byproduct of a change in some other perhaps more critical mechanism. Some alternative mechanisms for yoga’s effects may be related to the physiological impact of exercise, such as peripheral and/or central nervous system stimulation (Broman-Fulks & Storey, 2008; Smits et al., 2008; Stoller, Greuel, Cimini, Fowler, & Koomar, 2012) or modulating cortisol reactivity to stress (Berger & Owen, 1988; Schell, Ollolio, & Schoneke, 1993). In one study, moderate-intensity physical activity, which induces repeated autonomic arousal, was negatively associated with frequency of binge eating among individuals who were fearful of such autonomic sensations (i.e., high AS, a construct related to DT) and had a tendency to eat as a means of coping with negative affect (DeBoer et al., 2012).

There are several limitations to our study that are worth noting and that can guide future investigations. First, our limited sample size and, thus, statistical power may explain our mixed findings among DTS subscales. Though power estimates for determining our sample size were gathered using published guidelines (S. W. Raudenbush & Xiao-Feng, 2001), a greater number of participants and/or more-frequent assessments could have enhanced power for detecting clinically meaningful condition differences.

Second, using additional behavioral measures of DT would have corroborated our findings using self-reported DTS. Measuring broad DT, or general affect intolerance is difficult at this time, however. Current laboratory behavioral measures of DT (e.g., breath holding challenge, computerized frustration tasks) tend to tap only domain-specific types of distress (e.g., physical discomfort, frustration) and, consequently, have been poorly correlated with each other and with other self-report measures (Leyro et al., 2010; McHugh & Otto, 2012). This problem calls for development of additional behavioral DT measurement methods that can assess both the overarching construct of emotional DT, as in the DTS, as well as its subcomponents.

Without the inclusion of additional active study conditions, our study cannot make conclusions regarding the comparative effects of yoga to traditional exercise, to psychotherapy, or to a contact control intervention. We also cannot ascertain whether yoga is better suited as a stand-alone or adjunctive treatment. That is, yoga may best serve as a complimentary intervention to established cognitive-behavioral interventions for emotional and binge eating that also emphasize broader emotion regulation skills. In short, we are limited in our ability to draw conclusions concerning the specificity of yoga’s effects. Attrition represents a related limitation, as 25% of the yoga treatment condition prematurely terminated the study. Thus, we cannot confirm the effects found here to be a result of intended “dose” of yoga. Future studies should assess reasons for yoga dropout and dose underperformance to guide further yoga implementation strategies.

Further research is needed to investigate how and for whom yoga interventions will be most useful. It is possible that some groups require integrative treatment strategies to reduce their avoidant coping behaviors. One study showed that low DT and poor use of emotion regulation strategies were additively predictive of experiential avoidance (McHugh, Reynolds, Leyro, & Otto, 2013). This has application to our results, suggesting that enhanced cognitive capacity for handling distress (i.e., reduced Absorption) through yoga may be less relevant for emotional eaters who do not have available alternative emotion regulation strategies. For these individuals, yoga may be more useful as an adjunct to other cognitive and behavioral skills training.

Conclusion

This study offers preliminary evidence for the benefits of yoga interventions for problems characterized by elevated stress and poor affect regulation. First, our findings underscore the promise of hatha yoga practice for increasing DT and reducing emotional eating tendencies. Second, our mediation analyses revealed a particular component of the cognitive processing of distress – Absorption – mediated the effects of yoga on disordered eating. Interventions that aid in affect modulation and enhanced coping are crucial for reducing the public health burden of an array of psychological disorders, and this study provides support for further development of specialized, mind-body interventions for those low in DT.

Table 2.

Descriptive Data and Zero-order Relations among Predictor and Criterion Variables

| Variable Name | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DTS Total | - | .86** | .85** | .80** | .78** | .39** | −.40** | −.02 | −.05 |

| 2. DTS Tolerance | - | - | .70** | .60** | .53** | .36 | −.47** | −.15 | −.08 |

| 3. DTS Absorption | - | - | - | .57** | .47** | .49** | −.40** | .02 | .00 |

| 4. DTS Appraisal | - | - | - | - | .56** | .32* | −.24 | .14 | .04 |

| 5. DTS Regulation | - | - | - | - | - | .10 | −.17 | −.04 | −.16 |

| 6. FFMQ | - | - | - | - | - | - | −.41** | .03 | −.16 |

| 7. DEES | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .03 | .11 |

| 8. BMI | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .26 |

| 9. Condition | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01

References

- Adam TC, Epel ES. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior. 2007;91:449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Selby EA, Fink EL, Joiner TE. The multifaceted role of distress tolerance in dysregulated eating behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40(8):718–726. doi: 10.1002/eat.20471. http://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA. Self-focused attention and mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based treatment. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2009;38(sup1):15–20. doi: 10.1080/16506070902980703. http://doi.org/10.1080/16506070902980703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger BG, Owen DR. Stress reduction and mood enhancement in four exercise modes: Swimming, body conditioning, hatha yoga, and fencing. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 1988;59(2):148–159. http://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.1988.10605493. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ, Vujanovic AA, Moos R. Integrating anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and discomfort intolerance: A hierarchical model of affect sensitivity and tolerance. Behavior Therapy. 2009;40(3):291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.08.001. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisbon NM, Lowery GA. Mindfulness and levels of stress: A comparison of beginner and advanced hatha yoga practitioners. Journal of Religion and Health. 2011;50(4):931–941. doi: 10.1007/s10943-009-9305-3. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-009-9305-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman-Fulks JJ, Storey KM. Evaluation of a brief aerobic exercise intervention for high anxiety sensitivity. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal. 2008;21(2):117–128. doi: 10.1080/10615800701762675. http://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701762675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR, Zvolensky MJ. Distress tolerance and early smoking lapse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(6):713–733. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Palm KM, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Gifford EV. Distress tolerance treatment for early-lapse smokers: Rationale, program description, and preliminary findings. Behavior Modification. 2008;32(3):302–332. doi: 10.1177/0145445507309024. http://doi.org/10.1177/0145445507309024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Reed KMP, Bloom EL, Minami H, Strong DR, Lejuez CW, Hayes SC. Development and preliminary randomized controlled trial of a distress tolerance treatment for smokers with a history of early lapse. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15(12) doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt093. http://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntt093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Keough ME, Schmidt NB. Problematic alcohol and cannabis use among young adults: The roles of depression and discomfort and distress tolerance. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(9):1957–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.019. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujarski SJ, Norberg MM, Copeland J. The association between distress tolerance and cannabis use-related problems: The mediating and moderating roles of coping motives and gender. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(10):1181–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.014. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carei TR, Fyfe-Johnson AL, Breuner CC, Brown MA. Randomized controlled clinical trial of yoga in the treatment of eating disorders. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(4):346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.007. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis K, Osadchuk A, Katz J. An eight-week yoga intervention is associated with improvements in pain, psychological functioning and mindfulness, and changes in cortisol levels in women with fibromyalgia. Journal of Pain Research. 2011;4:189–201. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S22761. http://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S22761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBoer LB, Tart CD, Presnell KE, Powers MB, Baldwin AS, Smits JAJ. Physical activity as a moderator of the association between anxiety sensitivity and binge eating. Eating Behaviors. 2012;13(3):194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.01.009. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy for substance abusers. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2008;4(2):39–47. doi: 10.1151/ascp084239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas MJ, Buhr K, Ladouceur R. The Role of Intolerance of Uncertainty in Etiology and Maintenance. In: Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Mennin DS, editors. Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 143–163. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KD. The effectiveness of hatha yoga on symptoms of anxiety and related vulnerabilities, mindfulness, and psychological wellbeing in female health care employees. Dissertation Abstracts International. 2010;70:2403. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard T, Brach N, Hölzel BK, Noggle JJ, Conboy LA, Lazar SW. Effects of a yoga-based intervention for young adults on quality of life and perceived stress: The potential mediating roles of mindfulness and self-compassion. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2012;7(3):165–175. http://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2012.667144. [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Gaylord SA, Boettiger CA, Howard MO. Mindfulness training modifies cognitive, affective, and physiological mechanisms implicated in alcohol dependence: Results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42(2):177–192. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2010.10400690. http://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2010.10400690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granath J, Ingvarsson S, von Thiele U, Lundberg U. Stress management: A randomized study of cognitive behavioural therapy and yoga. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2006;35(1):3–10. doi: 10.1080/16506070500401292. http://doi.org/10.1080/16506070500401292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt J. Complete Yoga Book. New York: Schocken; 1990. Reissue edition. [Google Scholar]

- Holaway RM, Heimberg RG, Coles ME. A comparison of intolerance of uncertainty in analogue obsessive-compulsive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20(2):158–174. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.01.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins-DeBoer LB, Medina JL, Baird SO, Smits JAJ. Yoga for cortisol reactivity to stress and affective eating: A randomized controlled pilot study. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang FJ, Chien DK, Chung UL. Effects of hatha yoga on stress in middle-aged women. Journal of Nursing Research. 2013;21(1):59–66. doi: 10.1097/jnr.0b013e3182829d6d. http://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0b013e3182829d6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar BKS, Menuhin Y. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. New York: Schocken; 1995. Revised edition. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood G, Rampes H, Tuffrey V, Richardson J, Pilkington K. Yoga for anxiety: A systematic review of the research evidence. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005;39(12):884–891. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2005.018069. http://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2005.018069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Stice E, Kazdin A, Offord D, Kupfer D. How do risk factors work together? Mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(6):848–856. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.848. http://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levenstein S, Prantera C, Varvo V, Scribano ML, Berto E, Luzi C, Andreoli A. Development of the perceived stress questionnaire: A new tool for psychosomatic research. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1993;37(1):19–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90120-5. http://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(93)90120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Bernstein A, Vujanovic AA, McLeish AC, Zvolensky MJ. Distress tolerance scale: A confirmatory factor analysis among daily cigarette smokers. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2011;33(1):47–57. doi: 10.1007/s10862-010-9197-2. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-010-9197-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: A review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136(4):576–600. doi: 10.1037/a0019712. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0019712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. 1993 Retrieved from http://books.google.com.

- Linehan M. Dialectical behavioral therapy: A cognitive behavioral approach to parasuicide. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1987;1(4):328–333. http://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.1987.1.4.328. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; 2008. Multilevel Mediation Models; pp. 237–274. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. http://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maller R, Reiss S. Anxiety sensitivity in 1984 and panic attacks in 1987. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1992;6:241– 247. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Otto MW. Refining the measurement of distress intolerance. Behavior Therapy. 2012;43(3):641–651. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.12.001. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Reynolds EK, Leyro TM, Otto MW. An examination of the association of distress intolerance and emotion regulation with avoidance. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2013;37(2):363–367. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9463-6. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9463-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIver S, O’Halloran P, McGartland M. Yoga as a treatment for binge eating disorder: A preliminary study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2009;17(4):196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2009.05.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neacsiu AD, Rizvi SL, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy skills use as a mediator and outcome of treatment for borderline personality disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(9):832–839. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.017. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouwens MA, van Strien T, van der Staak CPF. Tendency toward overeating and restraint as predictors of food consumption. Appetite. 2003;40(3):291–298. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(03)00006-0. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(03)00006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash R, Dubey I, Abhishek P, Gupta SK, Rastogi P, Siddiqui SV. Long-term vihangam yoga meditation and scores on tests of attention. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2010;110(3C):1139–1148. doi: 10.2466/pms.110.C.1139-1148. http://doi.org/10.2466/pms.110.C.1139-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk A, Cheong YF, Congdon R. HLM 6: Hierarchical and nonlinear modeling [Computer software] Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Xiao-Feng L. Effects of study duration, frequency of observation, and sample size on power in studies of group differences in polynomial change. Psychological Methods. 2001;6(4):387–401. http://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.6.4.387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24:1– 8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell FJ, Allolio B, Schoneke OW. Physiological and psychological effects of Hatha-Yoga exercise in healthy women. International Journal of Psychosomatics: Official Publication of the International Psychosomatics Institute. 1993;41:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt NB, Richey JA, Fitzpatrick KK. Discomfort intolerance: Development of a construct and measure relevant to panic disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2006;20(3):263–280. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.02.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro D, Cook IA, Davydov DM, Ottaviani C, Leuchter AF, Abrams M. Yoga as a complementary treatment of depression: Effects of traits and moods on treatment outcome. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2007;4(4):493–502. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel114. http://doi.org/10.1093/ecam/nel114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. http://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM. The Distress Tolerance Scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29(2):83–102. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willet JD. Applied Longitudinal Data Analyses. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, Hancock H, Blake-Mortimer J, Eckert K. A randomised comparative trial of yoga and relaxation to reduce stress and anxiety. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2007;15(2):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.05.001. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits JAJ, Berry AC, Rosenfield D, Powers MB, Behar E, Otto MW. Reducing anxiety sensitivity with exercise. Depression and Anxiety. 2008;25(8):689–699. doi: 10.1002/da.20411. http://doi.org/10.1002/da.20411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoller CC, Greuel JH, Cimini LS, Fowler MS, Koomar JA. Effects of Sensory-enhanced yoga on symptoms of combat stress in deployed military personnel. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012;66(1):59–68. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2012.001230. http://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2012.001230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telch CF, Stewart W, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(6):1061–1065. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1061. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolin DF, Abramowitz JS, Brigidi BD, Foa EB. Intolerance of uncertainty in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2003;17(2):233–242. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00182-2. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6185(02)00182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uebelacker LA, Epstein-Lubow G, Gaudiano BA, Tremont G, Battle CL, Miller IW. Hatha Yoga for depression: Critical review of the evidence for efficacy, plausible mechanisms of action, and directions for future research. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2010;16(1):22–33. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000367775.88388.96. http://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000367775.88388.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien T, Frijters JER, Bergers GPA, Defares PB. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1986;5(2):295–315. http://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198602)5:2<295::AID-EAT2260050209>3.0.CO;2-T. [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien T, Frijters JER, van Staveren WA, Defares PB, Deurenberg P. The predictive validity of the Dutch Restrained Eating Scale. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1986;5(4):747–755. http://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198605)5:4<747::AID-EAT2260050413>3.0.CO;2-6. [Google Scholar]

- Van Strien T, Ouwens MA. Counterregulation in female obese emotional eaters: Schachter, Goldman, and Gordon’s (1968) test of psychosomatic theory revisited. Eating Behaviors. 2003;3(4):329–340. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(02)00092-2. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1471-0153(02)00092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zyphur MJ, Preacher KJ. Testing multilevel mediation using hierarchical linear models: Problems and solutions. Organizational Research Methods. 2009;12(4):695–719. http://doi.org/10.1177/1094428108327450. [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A, Vujanovic AA. Distress Tolerance: Theory, Research, and Clinical Applications. 2011 Retrieved from http://books.google.com.