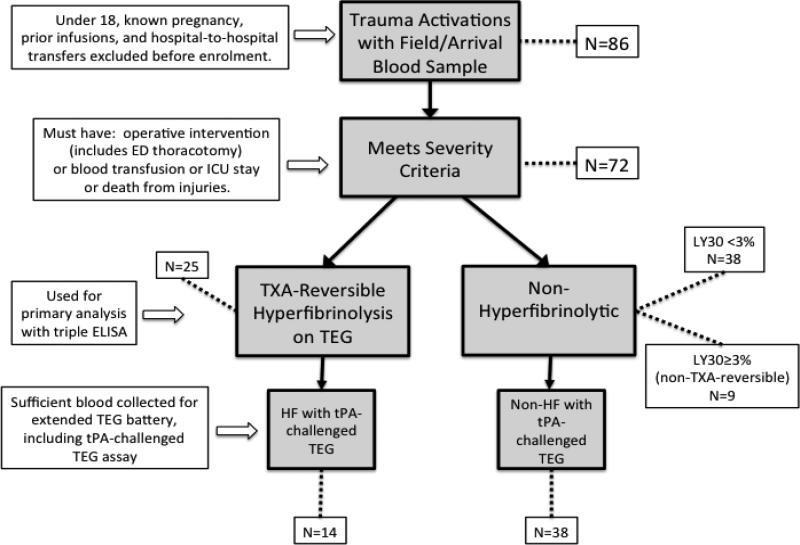

Figure 1. Flow chart of exclusion and inclusion at sequential steps in the analysis.

86 patients met initial enrolment criteria (highest level trauma activation) and had blood collected at the time of their initial vascular access, usually in the field. Patients under 18, known pregnancies and transfers were excluded as well as patients with documented coagulopathy or hepatic disease. As the determination of trauma activation by the paramedics in the field occasionally enrolls patients who are not in fact traumatically injured (e.g. medical illness only or severe substance intoxication), patients who did not actually have a traumatic injury of significant severity were excluded ex post facto. Criteria for severity were defined as injury requiring any operative intervention (including resuscitative thoracotomy), any blood product transfusion, injuries necessitating an ICU stay of any length or death from injuries (N=72). Hyperfibrinolytic patients (N=25) were discriminated from non-hyperfibrinolytic patients (N=47) by TXA-reversibility of apparent clot lysis. The conventional definition of hyperfibrinolysis in trauma of a TEG LY30 ≥ 3% was used, with the additional criteria that the observed lysis must be TXA-reversible, to eliminate false positives from platelet retraction (N=9). Initial blood sample volumes were not always sufficient to run the extended TEG battery that includes the tPA-challenged TEG assay; therefore, only a nested subset of the patients included in the basic TEG and ELISA data analysis have the additional data from the tPA-challenged TEG (N=52).