Abstract

Objective

Delirium superimposed on dementia (DSD) is common and potentially distressing for patients, caregivers, and health care staff. We quantitatively and qualitatively assessed the experience of informal caregiver and staff (staff nurses, nurse aides, physical therapists) caring for patients with DSD.

Methods

Caregivers’ and staff experience was evaluated three days after DSD resolution (T0) with a standardized questionnaire (quantitative interview) and open-ended questions (qualitative interview); caregivers were also evaluated at 1-month follow-up (T1).

Results

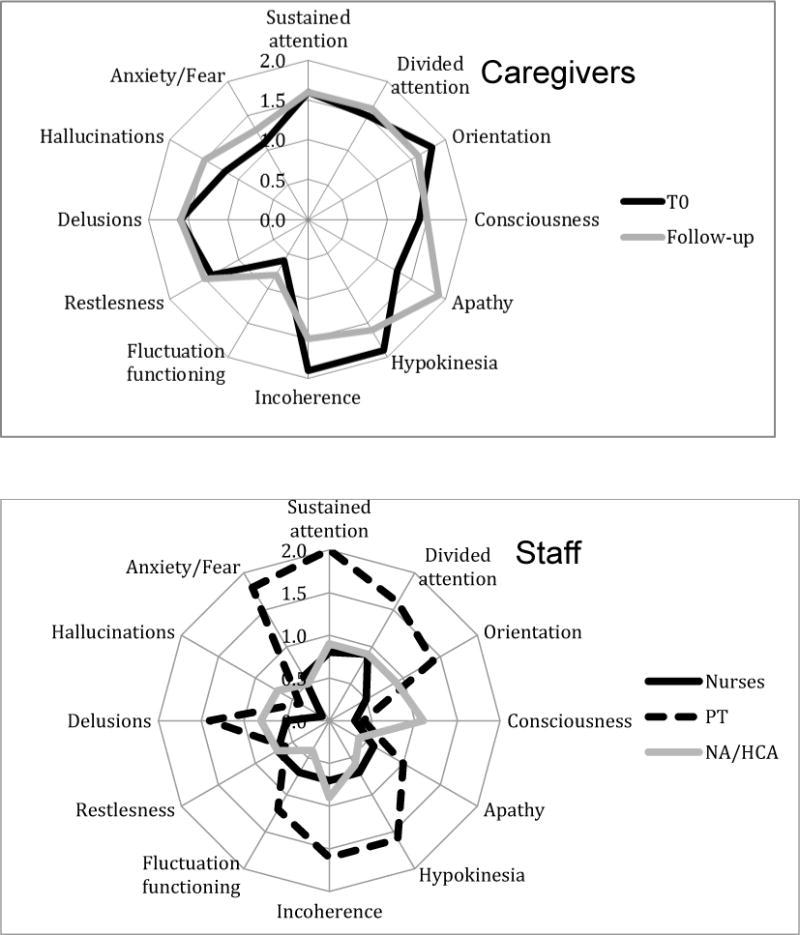

A total of 74 subjects were included; 33 caregivers and 41 health care staff (8 staff nurses, 20 physical therapists, 13 staff nurse aides/health care assistants). Overall, at both T0 and T1, the distress level was moderate among caregivers and mild among health care staff. Caregivers reported, at both T0 and T1, higher distress related to deficits of sustained attention and orientation, hypokinesia/psychomotor retardation, incoherence and delusions. The distress of health care staff related to each specific item of the Delirium-O-Meter was relatively low except for the physical therapists who reported higher level of distress on deficits of sustained/shifting attention and orientation, apathy, hypokinesia/psychomotor retardation, incoherence, delusion, hallucinations, anxiety/fear. The qualitative evaluation identified important categories of caregivers ‘and staff feelings related to the delirium experience.

Conclusions

This study provides information on the implication of the experience of delirium on caregivers and staff. The distress related to DSD underlines the importance of providing continuous training, support and experience for both the caregivers and health care staff to improve the care of patients with delirium superimposed on dementia.

Keywords: delirium superimposed on dementia, caregivers’ experience, stress

INTRODUCTION

Delirium is a common neuropsychiatric disorder defined by the DSM-5 1 as a disturbance in attention and awareness, and cognitive deficits that develop over a short period of time and fluctuate over the course of the day as a direct consequence of another medical condition or substance intoxication. When delirium occurs in patients with dementia, it is referred to as delirium superimposed on dementia.2 There is an important link between delirium and dementia. In fact dementia is an important risk factor for delirium and delirium is an important risk factor for the development or worsening of dementia. 3–5 The prevalence of delirium superimposed on dementia is extremely high in both community and hospital populations affecting between 22 % to 89% of patients.2 Delirium superimposed on dementia is associated with higher health care costs, worse functional outcomes and higher mortality rates compared to patients with dementia alone. 2, 6–9 Dementia per se affects about 35.6 million of people worldwide and about 30% of patients admitted to rehabilitation hospitals have dementia.6, 10

The care of patients with delirium and dementia separately leads to caregivers’ burden and requires a high level of assistance and training for health care staff.11, 12 The overlap of delirium with dementia is likely to significantly increase patients’ need for assistance not only for health care staff but also for the caregivers. Understanding the experience of health care staff and informal caregivers assisting patients with dementia is becoming increasingly important with the growing number of affected individuals. Given that dementia is one of the main risk factors for delirium, it is also imperative to understand the experience related to delirium superimposed on dementia.3–5

A few studies have explored the experience of informal caregivers and health care staff assisting patients with delirium admitted to intensive care, hospice, and orthopedic wards.12–19 The impact of delirium on informal caregivers is substantial14, 20–23 with a high level of distress reported including in some cases the development of long-term sequelae such as generalized anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.24–26 A recent review has additionally underlined how there is some understanding of delirium experience in palliative care settings but the lack of knowledge on this topic is even grater in acute care or long-term care settings.27 In fact there are few studies conducted specifically in older patients admitted to in specialty delirium unit, acute care wards, adult day care centers.28–30 Specifically Bull and colleagues29 reported a low level of distress of informal caregivers of patients with delirium attending an adult day care center. Interestingly they have also reported that about 96% of the caregivers did not have any knowledge about delirium, underlying the importance of delirium education and training. Outpatient studies examining the health care experience of the informal caregivers of patients with dementia report on their feelings of confusion, uncertainty, anxiety and tension.31 However, research examining the burden in informal caregivers of hospitalized older adults with dementia is scarce.11, 32, 33 Major factors linked to greater informal caregiver burden include: caregiver age, the spousal relationship status, caregiver depressive symptoms, limited finances, distress associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms.11 Caring for people with dementia professionally has also been described as emotionally and physically draining with high physical and psychological work-loads.34, 35 Intense involvement with nursing home residents has been identified as a stressor, which can lead to staff burnout. Staff reported relatively high level of distress, especially due to unpredictability of the workload related to delirium, issues of safety difficulties communicating with patients, being unable to decide when to be flexible and when in control of the patients’ behavior, and finally difficulties understanding the patients’ experience.12, 13, 36

To date, no study has specifically examined the experience of delirium superimposed on dementia in informal caregivers and health care staff. To address this gap in the literature, we have conducted this prospective cohort study to evaluate quantitatively and qualitatively the experience of informal caregivers and health care staff (i.e. nurses, physical therapists, nurse aides/health care assistants) caring for older patients admitted to an in hospital rehabilitation setting with delirium and dementia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a prospective cohort study of informal caregivers (i.e., family members or private caregivers who have been in contact with the patient during the delirium episode for at least an hour daily) and key health care staff (i.e. nurses, nurse aides/health care assistants and physical therapists who has been in contact with the patient for at least one shift during the delirium episode) who cared for older patients with dementia and incident (delirium at the time of rehabilitation admission) or prevalent (delirium during the rehabilitation stay). Patients were consecutively admitted to a 27-bed In-hospital rehabilitation ward within the Department of Rehabilitation of the Ancelle Hospital (Cremona, Italy) between September 2013 and May 2014. This setting has been previously described.6, 37 Patients were excluded if the authorized surrogate refused informed consent, if patients had delirium without dementia, or if patients could not self-report. At enrollment, we obtained informed consent from patients’ authorized surrogates; we subsequently also obtained consent from patients once they were deemed to be mentally competent. The informal caregiver and key health care staff for patients were then approached by AM to participate and included if they provided informed consent. The study was reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee.

Information on informal caregivers, health care staff, patients

We collected information on informal caregiver including age, gender, education level, and the relationship to the patient. We also gathered information on the health care staff on age, gender, and work experience. Information for patients included including age, gender, the level of functional and cognitive impairment, the delirium duration and severity. Patients’ functional status was assessed with the Barthel Index (BI) through patient and surrogate interview referring to the month before the acute hospital admission,38, 39 at rehabilitation admission, and at discharge.

Dementia ascertainment

Prior to enrollment we ascertained the presence and type of dementia (i.e., Vascular Dementia, Alzheimer Dementia, Lewy Body Dementia, Other) by reviewing patients’ medical records. Additionally, two expert neuropsychologists (EL, SM) confirmed and rated the severity of dementia interviewing the informal caregivers at the patients’ enrollment with the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Scale40 and the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE).41 The CDR ranges from 1 to 3: 1 (mild dementia); 2 (moderate dementia); 3 (severe dementia).

Delirium evaluation

Two expert geriatricians (AM, RT) diagnosed patients’ delirium according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition, text revision) (DSM-IV-TR) criteria with a standardized approach previously described.42 The geriatricians screened patients with dementia for the presence of delirium at the time of admission and daily during their hospital stay if they did not have delirium on admission. Delirium was evaluated twice-daily by AM, RT. The clinical (motor) subtype of delirium (i.e., hypoactive, hyperactive, mixed) was identified using the modified-Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (m-RASS).43 The m-RASS is derived from the RASS44, 45 and it has been modified to be used as an objective measurement of consciousness and a reliable screen for the presence or absence of delirium when administered longitudinally. When used to detect change, serial mRASS assessments had a sensitivity of 74% and a specificity of 92% (LR, 8.9) in both prevalent and incident delirium.43 Patients were categorized into two delirium motor subtypes according to the m-RASS score: hypoactive (RASS score between −1 and −3) and hyperactive (RASS score between +1 and +4).

Patient were considered delirium-free if they did not have delirium for three consecutive days as in a previous work.46 We evaluated the severity of delirium using the Delirium-O-Meter (D-O-M),47 a nurses’ rating scale for monitoring delirium severity in geriatric patients. The D-O-M reliability is high; Cronbach’s alpha values in the validation study ranged from 0.87–0.92; Intra Class Correlation (ICC) ranges were 0.84–0.91 for total scores and 0.40–0.97 for item scores.47 The D-O-M includes twelve symptoms of delirium: sustained inattention; shifting attention; orientation; consciousness disturbance; apathy; hypokinesia/psychomotor retardation; incoherence; fluctuation in functioning (diurnal variation/sleep wake cycle); restlessness (psychomotor agitation); delusions; hallucinations; and anxiety/fear. Each symptom is scored on a four-point scale (0=absent; 1=mild; 2=moderate; 3=severe). Total scores range from 0 to 36, with higher scores representing greater symptom burden. The two expert geriatricians completed the D-O-M with patients during the day and bedside nurses completed it overnight.

Quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the experience of delirium

Three days after the complete resolution of delirium, as described above, the caregivers were interviewed in person for the first evaluation (T0) by one of the two neuropsychologists (EL, SM). The structure questionnaire was handed and filled out by health care staff for each patient with a single evaluation (i.e. a health care staff member completed only one questionnaire per patient). Each subject was asked to describe the level of distress related to each item of the D-O-M on a Likert scale from 0–4 (0=no distress; 1=a little; 2=a fair amount; 3= very much; 4=extremely distressed). The same scale was used to provide a global level of distress from 0 to 4. Finally, each subject was asked to describe their overall experience of delirium with two open questions: “Can you please describe, with your own words, your experience caring for the patient during the delirium episode? Can you please describe what worried you the most?” The neuropsychologists informed the caregivers what days the patients were delirious so that the caregivers could focus their attention on those specific days. We specifically asked the caregivers to focus on the days the patients were delirious since we were interested on exploring the experience related to delirium superimposed on dementia and not to dementia and its related behavioral changes.

Caregivers were also evaluated for a second interview at 1-month follow-up (T1) by two neuropsychologists by telephone interview or in person if the patients were still in the hospital with the same questionnaire used for the first interview.

Method of analysis

We summarized demographic and quantitative interview data using descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, and percentages.

A total of at least 30 interviews were planned to be included as the sample size for the qualitative analysis, previously indicated by Creswell.48 We analyzed the open-ended interview questions regarding the overall experience of delirium using qualitative content analysis.49 The interviews were transcribed verbatim by EL and SM. Data were analyzed as described by Graneheim and Lundman.50 Four of the authors (EL, SM, AM, RT) began by reading each response several times to identify various reported aspects of the delirium experience. We then assigned common phrases or labels (e.g. if a caregiver reported being afraid, then the we assigned the label of “fear”). Next, we grouped common labels into broader categories by topic, (e.g., the label “fear” was included in a broader category of “emotions”) (Table 1). We created new codes and modified categories in an iterative process as we read each response. When all data was reviewed and coded, we reapplied the final coding scheme to all responses. In case of disagreement between the four authors the process was repeated until a final consensus was achieved. Finally, for descriptive purpose the interviews were translated into English by AM. The qualitative evaluation of caregivers at the first evaluation (T0) and at the follow-up (T1) was combined to report the overall caregivers’ feelings.

Table 1.

Caregivers and staff feelings reported from qualitative interview after delirium resolution.

| Main Categories | Subcategories | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregivers | Perceived aspect of patients experience | Cognitive impairment | Disorientation, confusion: “He does fluctuate at home as well, especially when he’s not engaged by anybody.. but this was different.. an incomprehensible speech.. I couldn’t understand what he was saying…”; |

| Aggressive behavior | Aggressiveness: “she became aggressive even with the hospital staff.. she did not want to take her pills”; profanity: “He was swearing.. he was agitated and getting mad with me..”; irritability: “she was irritable, restless, her thoughts keep changing”; shouting and agitation: “he was agitated.. he was shouting..he was pulling away everything he had on his body… before coming here he had been restrained for 12 days..” | ||

| Psychosis | Hallucinations and delusions: “He starts having thoughts about unreal and strange things..”; “he thought I was his sister.. he was seeing his father, his mom.. people who are already dead”. | ||

| Aspects of caregivers experience | Concerns about present situation | Low care ability: “I do not know this disease.. I don’t know how to deal with it..”; inability to communicate: “you do not know how to communicate with him.. he is in another world and you don’t know what he needs”; | |

| pain/suffering: “I was worried she realized what was happening and she would suffer about it..”; altered vigilance: “it hit me that she kept falling asleep and could not follow my thoughts”; cognitive and physical symptoms: “I thought it was a sign of imminent death. I’m afraid that those episodes could worsen her physical condition more than the previous stroke.. when I saw her she was febrile and I thought it was the flue that caused the confusion.” | |||

| Concerns about the future | Loss: “I was worried about my mother.. I thought she would not make it through the hospitalization.. I felt like I have already lost her”; Symptom persistence: “I understand this episode will change our lives… we have to think about alternative solutions.”; Institutionalization, home discharge: “I was afraid I would not be able to take care of her at home..and I would have to institutionalize her”; Fear of becoming ill: “when I take care of these patients I eventually get sick as well..”; Fear of dementia: “my father had Alzheimer disease and I would not like to see my mother in the same situation.. I am wondering if this is the beginning of an Alzheimer dementia?”; Helplessness: “I was worried I could not help him anymore in the future.. the loss of an important relationship..”; Euthanasia: “I saw her as a different person.. she’s not like she was before.. I still love her.. I have rumbling thoughts about my view on euthanasia.” | ||

| Awareness of change | Sudden change, fluctuation in severity of symptoms: “A total change.. he was picking at the bed linens without any reason… he kept moving his hands.. he was moving in a strange way..illogical thoughts..”; “the sudden change of a person who could drive a car and invest money only few days before and then… it was the speed of that change that worried me..”. | ||

| Aspects of patients and caregiver experience* | Emotions1 | Depression and fear: “I saw my mother more depressed.. she cried and I have never seen her crying… she said she was sad and frightened..” | |

| Emotions2 | Suffering: “I suffer seeing her in this condition… it makes me anxious.. it is an unpleasant situation..”; Anxiety: “I cannot forget what happened and it makes me anxious..”; Anguish: “I didn’t know what to do..and it caused me anguish..”; Fear, Disbelief: “I was really afraid of her hallucinations.. I still cannot believe it happened to her..”; Depression: “I kept crying seeing him in this condition… I was thinking that my dad would become crazy..and it made me depressed” | ||

| Physical symptoms1 | Somnolence: “It hit me that he kept falling asleep.. he could not follow a conversation”; Loss of appetite “she was apathetic. she would not eat and she did not want anybody to help her.”; fluctuation: “during the first days he was so sedated he could not even talk.. and then he was agitated” | ||

| Physical symptoms2 | Loss of appetite related to themselves. “I completely lost my appetite.. I feel really apprehensive when I’m not there and I keep thinking about her.” | ||

| Care1 | Benefit of family presence: “He kept looking for me..”; loss of autonomy: “she was functionally independent before this happened and then totally dependent.” Care load: “Caring for him was extremely demanding.” | ||

| Care2 | Issues with care load: “I did not know how to manage her..”; Benefitting from family presence “when I was with her she was more cooperative. She trusted me more than the staff”; Relief from hospital stay: “I knew that when she was at the hospital I was not by myself but there were people more competent than me who could help us..” | ||

| Staff | |||

| Emotions | Apathy: “the patient was showing apathy and she would just sit and wait for us..”; Loss of dignity: “ It made me sad seeing this patient loosing her dignity… I knew her before she became delirious”; Anxiety, fear, distrust: “the anxiety and fear when his relatives were not there and the distrust for the staff members.”; Depression: “the patient was depressed, empty, difficult to stimulate”; Anger: “I remember the anger and the aggressive behavior when he could not understand how to perform a rehabilitative procedure.” | ||

| Cognitive impairment | Difficulties in communication, distractibility: “It was impossible to communicate with her, she could not keep her attention”; Confusion, disorientation: “He was disoriented, confused, with an important inattention, slow in his responses and with an inappropriate behavior”; “she was saying words with no sense”; Unawareness: “I was worried about the total unawareness.” | ||

| Awareness of change | Sudden change: “She was a normal person and then she suddenly changed, she became confused.. repetitive questions, verbalizations during the day and at night.. she was refusing the rehabilitation treatment…”; Change back to reality: “I didn’t know if he would have changed back to a normal status.” | ||

| Aggressive behavior Physical symptoms | Aggressiveness: “he was aggressive towards the staff members.. it was difficult to feed her..”; irritability, shouting: “he kept trying getting out of bed.. he would not sit in his chair for more than five minutes.. he was shouting.. anxious.. and he was afraid of the surrounding..”. | ||

| Fluctuation of functional status, sleep cycle alteration, pain | |||

| Psychosis | Illogical thoughts, hallucinations: “Frequent visual hallucinations especially in the afternoon making the rehabilitative process extremely challenging..”; “the hallucinations were so severe she could not even communicate.. she was seeing animals hurting her..” | ||

| Adequacy of care | Benefit of family presence: “when the family members were present he was more lucid and co-operative.”; Incomprehension of patient’s need: “it was difficult to understand the patients’ need and therefore provide adequate care..”; Work load, agitation in other patients: “the patient needed assistance 24 hours a day… he was shouting, anxious, aggressive… the other patients were afraid… he would not make the other patients sleep..”; Modification of care: “It was difficult to find the required time to face her anxiety and fear when you need to care other patients simultaneously…. caring for delirious patients requires a lot of time and it requires changes in the regular work schedule”; Patient’s collaboration: “I needed to provide clear and brief indications during the rehabilitation treatment.. at some point was oppositional…” Loss of autonomy, functional dependence: “he was totally dependent.. he needed a person 24 hours a day..” | ||

| Other concerns | Time for care, reduced time for other patients: “I was worried I did not have enough time to care for this patient.. I could not provide reassurance, help and encouragement to the patient..”; Risk of falls: “I was worried about the risk of falling because of agitation”; Unpredictability: “I was worried about her unpredictable behaviour..”; helplessness: “My actions were not changing the situation.. they appeared to me to be useless”; frustration: “it is frustrating because these patients need to have somebody caring for them continuously but you can’t since you have to care also for other patients”; | ||

| loneliness: “when I was testing his functional status he appeared to be suffering.. I thought he could fall because of his pain.. I felt like I was alone caring for him.”; reassurance and stimulation attempts: “I could not transfer her a feeling of security, courage.. I could not reassure him; fluctuation: “the patient appeared disoriented and hypokinetic.. he was apathic and non reactive to the indications.. his behavior was non adequate and fluctuating..” | |||

| cognitive and physical symptoms: “caring for him was problematic because his level of consciousness was altered..pyschomotor agitation, confusion.. causing risks for his physical safety”; needs identification: “it was difficult to understand her needs and provide adequate care.”; relatives’ expectation “I was worried about her husband expectation of recovery.” |

Feelings reported by caregivers related to patients experience during delirium episodes.

Feelings reported by caregivers related to themselves during patients delirium episodes.

RESULTS

A total of 74 subjects were included; 33 caregivers and 41 health care staff (8 staff nurses, 20 physical therapists, 13 staff nurse aides/health care assistants).

Participants’ characteristics are described in Table 2. A total of 150 questionnaires were completed by nurses, 29 by physical therapists, and 143 by nurse aides/health care assistants. Informal caregivers were relatively young (59± 12.9 years old), mostly female (81%), and were adult child of the patient (60%). About 70% had more than nine years education.

Table 2.

Description of informal, caregivers, health care staff and patients.

| Caregivers | n = 33 |

|---|---|

| Age | 59 ± 12.9 |

| Gender (female) (n, %) | 27 (81) |

| Relationship to patient, (n, %) | |

| - Spouse | 6 (18) |

| - Adult child | 20 (60) |

| - Other* | 7 (21) |

| Education level (n, %) | |

| - <6 years | 3 (9) |

| - 6–9 years | 7 (21) |

| - 9–12 years | 16 (48) |

| - College/Graduate school | 7 (21) |

| Staff Nurses | n = 8 |

| Age | 37.4 ± 7.6 |

| Gender (female) (n, %) | 6 (75) |

| Work experience (years) | 14 ± 7.5 |

| Questionnaires completed | n =150 |

| Staff Physical Therapists | n = 20 |

| Age | 37 ± 3.6 |

| Gender (female) (n, %) | 16 (80) |

| Work experience (years) | 7.5 ± 3.5 |

| Questionnaires completed | n = 29 |

| Staff Nurses Aides/ Health Care Assistants | n = 13 |

| Age | 41 ± 5.1 |

| Gender (female) (n, %) | 13 (100) |

| Work experience (years) | 12.5 ± 7.2 |

| Questionnaires completed | n = 143 |

| Patients | n =35 |

| Age | 83 ± 6.1 |

| Gender (female), (n, %) | 23 (66) |

| Barthel Index pre-admission | 72 ± 26 |

| Barthel Index admission | 22 ± 19 |

| Barthel Index discharge | 43 ± 28 |

| CDR total | 1.8 ± 0.7 |

| CDR 1 (n, %) | 15 (43) |

| CDR 2 (n, %) | 13 (37) |

| CDR 3 (n, %) | 7 (20) |

| Duration of delirium (days) | 4.7 ± 4.3 |

| Hypoactive delirium (episodes) | 1.2 ± 1.5 |

| Hyperactive delirium (episodes) | 0.5 ± 1.1 |

| D-O-M maximum score | 17 ± 5.8 |

| D-O-M maximum score during hypoactive episode | 18±5.6 |

| D-O-M maximum socre during hyperactive episode | 20±5.5 |

Siblings, private caregivers, friends.

Abbreviations: CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale; D-O-M, delirium-O-meter.

Of the health care staff, nurses had a mean age of 37.4 years ± 7.6 and were professionally experienced (14 years ± 7.5). Physical therapists had a mean age of 37 years ± 3.6 and moderate work experience (7.5 years ± 3.5). Nurse aides/health care assistants were older (41 years ± 5.1) and professionally experienced (12.5 years ± 7.2).

The patients’ characteristics are described in Table 2. In particular, the patients’ mean duration of delirium was 4.7 days (± 4.3 days), with a moderate severity as described by the D-O-M maximum score (17 ± 5.8). The D-O-M maximum score during the hypoactive episodes was 18 ± 5.6 and the D-O-M maximum score during the hyperactive episodes was 20 ± 5.5.

Quantitative evaluation

Informal caregivers

Among the informal caregivers (N=33) the mean distress level was moderate and was higher at the first evaluation (T0) (2.3± 1.1) than (1.9± 1.12) at 1-month follow-up (T1). Informal caregivers reported higher distress than health care staff related to deficit of sustained attention and orientation, hypokinesia/psychomotor retardation, incoherence, hallucinations, and delusions (Table 3; Figure 1).

Table 3.

Mean distress level related to each Delirium-O-Meter item in caregivers at the first evaluation (T0) and at follow-up (T1); staff members (Nurses, Physical therapists (PT), Nurses assistants/Health care assistants (NA/HCA).*

| Variable | Caregivers first evaluation | Caregives follow-up | Nurses | PTs | NAs/HCAs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained attention | 1.6 (± 1.4) | 1.6 (± 1.4) | 0.8 (± 1.1) | 2 (± 1.2) | 0.9 (± 1.3) |

| Shifting attention | 1.5 (± 1.4) | 1.6 (± 1.4) | 0.9 (± 2.0) | 1.6 (± 2.5) | 0.9 (± 1.0) |

| Orientation | 1.8 (± 1.5) | 1.6 (± 1.4) | 0.5 (± 0.9) | 1.4 (± 1.7) | 0.9 (± 1.6) |

| Consciousness | 1.4 (± 1.4) | 1.5 (± 1.5) | 0.3 (± 0.7) | 0.4 (± 0.9) | 1.1 (± 1.4) |

| Apathy | 1.3 (± 1.4) | 1.9 (± 1.6) | 0.6 (± 0.8) | 1 (± 1) | 0.4 (± 0.6) |

| Hypokinesia/psychomotor retardation | 1.9 (± 1.6) | 1.6 (± 1.5) | 0.7 (± 1.2) | 1.6 (± 1.5) | 0.6 (± 0.8) |

| Incoherence | 1.9 (± 1.6) | 1.5 (± 1.6) | 0.7 (± 1.3) | 1.6 (± 0.9) | 0.9 (± 0.9) |

| Fluctuation in functioning | 0.6 (± 1.1) | 0.8 (± 1.3) | 0.7 (± 1.3) | 1.2 (± 1.3) | 0.4 (± 0.7) |

| Restlesness | 1.4 (± 1.6) | 1.5 (± 1.7) | 0.7 (± 1.3) | 0.6 (± 0.9) | 0.7 (± 0.9) |

| Delusions | 1.6 (± 1.7) | 1.6 (± 1.7) | 0.5 (± 1.2) | 1.4 (± 1.5) | 0.8 (± 1.2) |

| Hallucinations | 1.2 (± 1.8) | 1.5 (± 1.8) | 0.1 (±0.3) | 0.4 (±0.9) | 0.7 (±0.8) |

| Anxiety/fear | 1.1 (± 1.5) | 1.3 (± 1.2) | 0.6 (± 1.2) | 1.8 (±0.8) | 0.5 (± 0.7) |

Each subject was asked to describe the level of stress related to each specific item of the D-O-M on a scale from 0–4 (0=no distress; 1=a little; 2=a fair amount; 3= very much; 4=extremely distressed).

Figure 1.

Radar plot of mean distress for each D-O-M items in caregivers at the first evaluation (T0) and at follow-up; staff members (Nurses, Physical therapists (PT), Nurse aides/Health care assistants (NA/HCA)

Health care staff

Among nurses (N=8), the mean distress level was lower (0.8± 0.7) than among physical therapists (N=20) (1.1± 1.2), and nurse aides/health care assistants (N=13) (1.1± 1.1). We confirmed a lower level of distress among health care staff on each item of the D-O-M. However, physical therapists reported higher levels of distress related to deficits of sustained/shifting attention and orientation, apathy, hypokinesia/psychomotor retardation, incoherence, delusions, anxiety/fear.

Qualitative Evaluation

Qualitative results are summarized in Table 1.

Informal caregivers

Informal caregivers’ reports of the delirium experience were more specific and detailed compared to those of patients with delirium superimposed on dementia, which we have described in the paired article of this journal issue.

Based on the two qualitative interviews at T0 and at follow-up (T1), informal caregivers experience of caring for patients with delirium superimposed on dementia fell into three main categories: perceived aspects of patient experience; aspects of caregiver experience; and aspects of both the patient and caregiver experience. We discuss each category below.

Perceived aspects of patient experience

Perceived aspects of the patient experience included the subcategories of cognitive impairment, aggressive behavior, and psychosis. Cognitive impairment was reported to include the cognitive symptoms of disorientation and confusion. Aggressive behavior included aggression, profanity, irritability, shouting and agitation. Psychosis included reported hallucinations and delusions.

Aspects of caregiver experience

Aspects of the caregiver experience included the subcategories of awareness of change, present and future concerns. Awareness of change was characterized by sudden change and fluctuation in severity of symptoms. Caregivers reported many concerns about the present situation, in particular low care ability, inability to communicate, pain/suffering, altered vigilance, cognitive and physical symptoms.

Caregivers’ concerns also referred to the future. In particular, they reported concerns about loss, symptom persistence, institutionalization, home discharge, fear of becoming ill, fear of dementia, helplessness, and euthanasia.

Aspects of patients and caregiver experience

Feelings were reported by caregivers related to patients experience during delirium episodes (i.e. caregiver perceptions related to patient experience) and related to themselves during patients’ delirium episodes.28–30 Aspects common to both the patient and caregiver experience were emotions, physical symptoms, and care. Caregivers reported different feelings related to patients experience during delirium episodes including depression and fear. Caregivers reported a greater number of feelings related to themselves during patients delirium episodes, including suffering, anxiety, anguish, fear, disbelief, and depression.

Physical symptoms pertaining to patients during delirium episodes included somnolence, loss of appetite, and fluctuation, while the physical symptom pertaining to caregivers was loss of appetite. Concerns about patient care included benefit of family presence, loss of autonomy, and care load. Finally, staff reported concerns related to the care load.

Health care staff

The provision of care category was the main source of concern for health care staff. Staff worried about the inability to understand the patients’ needs and to provide appropriate care. Overall, health care staff reported little distress related to the management of delirious patients, except in regard to patients with severe symptoms, e.g., aggressive behavior.

We identified eight categories of health care staff concerns: emotions; cognitive impairment; awareness of change; aggressive behavior; physical symptoms; psychosis; adequacy of care; and other miscellaneous concerns. We summarize each categories and its subcategories below.

Emotions

Staff members reported different emotions related to their experience caring for patients during delirium episodes. These included apathy, loss of dignity, anxiety, fear, distrust, depression, and anger.

Cognitive impairment

Staff members reported different feelings related to cognitive impairment. In particular they reported difficulties in communication, distractibility, Confusion, disorientation, and Unawareness.

Awareness of Change

The staff reported also feelings about sudden change and Change back to reality.

Aggressive behavior, physical symptoms, and psychosis

Staff reported different feelings including aggressiveness, irritability, shouting, fluctuation of functional status, pain, illogical thoughts, and hallucinations.

Adequacy of Care

Staff also reported concerns about adequacy of care including benefit of family presence, incomprehension of patient’s need, workload, agitation in other patients, modification of care, patient’s collaboration, loss of autonomy, and functional dependence.

Other concerns

Finally, several other concerns were reported by staff including time for care, reduced time for other patients, risk of falls, unpredictability, helplessness, frustration, loneliness, reassurance and stimulation attempts, fluctuation, cognitive and physical symptoms, needs identification and relatives’ expectation.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to report both quantitatively and qualitatively the experience of informal caregivers and health care staff assisting patients with delirium superimposed on dementia admitted to a rehabilitation setting. Informal caregivers reported a moderate distress level both at the first evaluation (T0) and at 1-month follow-up. Informal caregivers reported higher distress specifically related to deficits of sustained attention and orientation, hypokinesia/psychomotor retardation, incoherence, hallucinations, and delusions. There was a slight increase in distress level at 1-month follow-up (T1) related to apathy, hallucinations, and anxiety/fear. The qualitative evaluation identified twelve main categories of informal caregivers’ feelings (cognitive impairment, aggressive behavior, psychosis, concerns about present situation and about the future, awareness of change; perceptions of emotions, physical symptoms and care reported by caregivers related to patients experience; emotions, physical symptoms and care reported by caregivers related to themselves). Interestingly, the distress was relatively low in health care staff. The distress of health care staff related to each specific item of the D-O-M was relatively low expect for the physical therapists who reported higher level of distress on deficits of sustained/shifting attention and orientation, apathy, hypokinesia/psychomotor retardation, incoherence, delusion, anxiety/fear. The qualitative evaluation identified eight main categories of staff’ feelings (emotions, cognitive impairment, awareness of change, aggressive behavior, physical symptoms, psychosis, adequacy of care, other concerns).

Informal caregivers and staff distress

Previous studies have reported an important association between delirium and distress in informal caregivers of patients with delirium.14, 20–23 However, these studies have included mainly patients with cancer and in hospice settings. In most studies informal caregivers reported moderate to severe distress related to the delirium experience. Interestingly, Buss and colleagues23 found that informal caregivers of patients with delirium were twelve times more likely to develop generalized anxiety. A few studies have included caregivers of older patients without cancer or admitted to hospice settings. 28–30 Specifically caregivers of patients admitted to a delirium unit described a distressing experience though the authors did not investigate the level of distress.28 Interestingly caregivers of patients with delirium and delirium symptoms attending adult day care experienced lower level of distress compared to the studies of patients with cancer or admitted to hospice.29 The authors postulated that these findings might be due to the fact that caregivers of older adults could mistakenly attribute the symptoms of delirium to ageing rather an acute mental status change.29 Our results indicate the presence of moderate distress even in informal caregivers of patients with delirium superimposed on dementia and, although we did not assess specifically the presence of post-traumatic stress disorder or generalized anxiety, we found that distress symptoms were still present at one-month follow-up and of moderate intensity. However, the absence of a control group of patients with dementia without delirium limits the interpretation of our findings.

In previous studies, staff distress caring for delirium patients mainly involved nurses and was reported to range from severe distress to relatively low.12, 14, 22, 36 In our study we found relatively low levels of distress among nurses with a slightly higher level of distress among nurses aids and physiotherapists. Bruera and colleagues22 also found a lower level of distress among nurses compared to family members and the authors hypothesized that this might reflect the high level of training and experience of the nurses caring for delirium patients along with the consistent presence of a physician expert in delirium care. These explanations might also apply to our setting because the nurses are well trained in delirium management and two expert geriatricians are present six days a week. The interpretation of a lower distress related to high level of training in the management of delirious patients strongly support the continuous education of health care providers on delirium and its related outcomes.

Informal caregiver and staff-specific symptoms and feelings

A recent review 36 of qualitative and quantitative studies evaluating the experience of delirium in informal caregivers and staff highlighted the main symptoms that are associated with distress.

For informal caregivers these included anxiety, exhaustion, helplessness, frustration, and stressfulness. Interestingly, a higher level of distress in the informal caregivers was related to the recall of psycho-motor agitation, hallucinations, delusional thoughts and the hyperactive subtype of delirium.14, 22, 36 Similarly, in our investigation informal caregivers reported higher levels of distress related to psychomotor retardation and delusions. Additionally, compared to other studies, informal caregivers of delirium superimposed on dementia patients recalled and reported higher distress related to apathy and alteration in orientation. From the qualitative interviews, we found that informal caregivers reported more concerns related to the future and their ability to cope with the sequelae of delirium. Specifically, many informal caregivers were worried about the potential need for institutionalization or the possible long-term effects on cognitive performance.

The existing literature on cancer patients with delirium indicates that nurses frequently recall psycho-motor agitation and disorientation.22 The presence of delusions and disturbances in the sleep wake-cycle have been reported as a major predictor of distress in nurses caring for cancer patients.14 In our investigation, we were able to evaluate the level of distress related to specific delirium symptoms both in nurses and in nurses’ aids and physiotherapists. Interestingly, the nurses and nurses’ aids did not report high level of distress related to specific D-O-M items apart from that related to the divided attention and the altered consciousness. Conversely, although physiotherapists reported relatively low overall level of distress, they reported higher level of distress related to psychomotor retardation, incoherence, disorientation, anxiety/fear and problems with sustained attention. These findings are in keeping with what one would expect. In fact all these symptoms related to delirium are very likely to interfere with the rehabilitative process leading to high distress in physiotherapists who cannot deliver a regular rehabilitative intervention.

Previous qualitative studies have focused upon nurses13, 16, 30 and nurse aides.17 Most of the qualitative research conducted on staff highlighted specific themes around the unpredictability of delirium, workload, safety issues, difficulties communicating with the patient, and conflict between providing adequate care for the delirious patients and not neglecting other non-delirious patients.12, 13, 36 Our findings concur with these previous investigations and highlight concerns about the workload required to care for delirious patients and inability to provide the regular care for patients without delirium especially in the cases of patients with hyperactive delirium with hallucinations and/or delusions. We also found frequent difficulties understanding patients’ needs and identifying communication strategies during the fluctuation course of delirium.

The findings of our study have important implications for the management of patients with delirium superimposed on dementia. Overall, we did not find major differences in the experience of delirium between informal caregivers and staff caring for delirious patients. There are a few possible explanations for these findings. Informal caregivers of patients with dementia are likely accustomed to the occurrence of neuropsychological symptom from previous episodes of delirium. Nonetheless, we are not able to provide further insight on this possible explanation because we did not specifically collect this information. Another explanation might be that the study was conducted in a rehabilitation ward where there is a high knowledge of delirium and health care staff involved might have been particularly supportive of caregivers. Still, the distress related to delirium superimposed on dementia in informal caregivers was substantial and clinicians should be aware of the important implications for clinical practice. It has been recommended that caregivers be provided with specific information sheets (e.g. pamphlets) that explain the background and management of delirium. Gagnon and colleagues51 found that a psychoeducational intervention for caregivers caring for terminally ill cancer patients increased knowledge of delirium. Future work should test the effect on caregivers’ distress of a direct psychological interventions during and after delirium episodes.

Health care staff in our institution might indeed be well trained in the management of delirium, but they are also well trained in the management of patient with dementia since, as previously noted,6 about 30% of the patients admitted to our department have dementia. The relatively modest level of distress found in our study further supports the importance of adequate delirium training for health care staff caring for older patients. In fact health care staff care for many patients with delirium and even the low-grade degree of distress may cumulative become much higher on the long-term than is experienced by informal caregivers. This information is extremely important because poor knowledge of delirium is an important barrier to improving its detection and management.52, 53

Our study has some important strengths and limitations. This is the first study to evaluate the quantitative and qualitative experience of informal caregivers of patients with delirium superimposed on dementia alongside a range of health care staff. We were able evaluate informal caregivers after the resolution of delirium and at 1-month follow-up with a rigorous interview performed by trained neuropsychologists. Limitations include the single center nature of the study, and the relatively small number of informal caregivers and health care staff, which limit our ability to identify specific predictors of distress. Another important limitation is that there is no control group of patients with dementia without delirium limiting our ability to compare distress related to delirium to behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Finally, we have chosen a total sample of at least 30 patients as reported in the methods following previous rules on qualitative research.48 Several approaches have been reported to ensure thematic saturation and there are no specific guidelines or tests of adequacy for estimating the sample size required to reach saturation.48, 54, 55 Future studies should include additional methods to further evaluate thematic saturation in this important and emerging research field.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides novel information regarding the experience of informal caregivers and health care staff assisting patients with delirium superimposed on dementia in a rehabilitation setting. Overall, the distress level was moderate in informal caregivers, while the distress in health care staff was relatively low. Informal caregiver distress was related to specific delirium symptoms such as deficit of sustained attention and orientation, hypoactivity, incoherence and delusions. The distress of health care staff was related to deficits of sustained/shifting attention and orientation, apathy, hypoactivity, incoherence, delusions, and anxiety/fear. The qualitative evaluation identified important categories of caregivers’ and staff feelings related to the delirium experience. The findings support the importance of providing education, training, and support for formal and informal caregivers regarding delirium superimposed on dementia, which is an important area resulting in a substantial degree of caregiver burden in both groups.

Acknowledgments

Fundings: Dr Inouye, Dr Schmitt and Dr Schulman-Green are supported by R01AG044518 (SKI) and K07AG041835 (SKI) from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

Contributor Information

Elena Lucchi, Email: elena.lucchi@ancelle.it.

Renato Turco, Email: renatoturco@virgilio.it.

Sara Morghen, Email: morghen-sara@ancelle.it, sara.morghen@ancelle.it.

Fabio Guerini, Email: fabio.guerini@ancelle.it.

Simona Gentile, Email: simona.gentile@ancelle.it.

David Meagher, Email: david.meagher@ul.ie.

Philippe Voyer, Email: philippe.voyer@fsi.ulaval.ca.

Donna M. Fick, Email: dmf21@psu.edu.

Eva M. Schmitt, Email: EvaSchmitt@hsl.harvard.edu.

Sharon K. Inouye, Email: sharoninouye@hsl.harvard.edu.

Marco Trabucchi, Email: trabucchi.m@grg-bs.it.

Giuseppe Bellelli, Email: giuseppe.bellelli@unimib.it.

Bibliography

- 1.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. fifth. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia: A systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50:1723–1732. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis DH, Muniz Terrera G, Keage H, Rahkonen T, Oinas M, Matthews FE, Cunningham C, Polvikoski T, Sulkava R, MacLullich AM, Brayne C. Delirium is a strong risk factor for dementia in the oldest-old: A population-based cohort study. Brain: a journal of neurology. 2012;135:2809–2816. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis DH, Skelly DT, Murray C, Hennessy E, Bowen J, Norton S, Brayne C, Rahkonen T, Sulkava R, Sanderson DJ, Rawlins JN, Bannerman DM, MacLullich AM, Cunningham C. Worsening cognitive impairment and neurodegenerative pathology progressively increase risk for delirium. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry: official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2015;23:403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fong TG, Jones RN, Shi P, Marcantonio ER, Yap L, Rudolph JL, Yang FM, Kiely DK, Inouye SK. Delirium accelerates cognitive decline in alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;72:1570–1575. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a4129a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morandi A, Davis D, Fick DM, Turco R, Boustani M, Lucchi E, Guerini F, Morghen S, Torpilliesi T, Gentile S, Maclullich AM, Trabucchi M, Bellelli G. Delirium superimposed on dementia strongly predicts worse outcomes in older rehabilitation inpatients. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2014;15:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.12.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampson EL, Blanchard MR, Jones L, Tookman A, King M. Dementia in the acute hospital: Prospective cohort study of prevalence and mortality. The British journal of psychiatry: the journal of mental science. 2009;195:61–66. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.055335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fick DM, Steis MR, Waller JL, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia is associated with prolonged length of stay and poor outcomes in hospitalized older adults. Journal of hospital medicine: an official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2013;8:500–505. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellelli G, Frisoni GB, Turco R, Lucchi E, Magnifico F, Trabucchi M. Delirium superimposed on dementia predicts 12-month survival in elderly patients discharged from a postacute rehabilitation facility. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences. 2007;62:1306–1309. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.11.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2013;9:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shankar KN, Hirschman KB, Hanlon AL, Naylor MD. Burden in caregivers of cognitively impaired elderly adults at time of hospitalization: A cross-sectional analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62:276–284. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Malley G, Leonard M, Meagher D, O’Keeffe ST. The delirium experience: A review. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2008;65:223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belanger L, Ducharme F. Patients’ and nurses’ experiences of delirium: A review of qualitative studies. Nursing in critical care. 2011;16:303–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2011.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breitbart W, Gibson C, Tremblay A. The delirium experience: Delirium recall and delirium-related distress in hospitalized patients with cancer, their spouses/caregivers, and their nurses. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:183–194. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stenwall E, Sandberg J, Eriksdotter Jonhagen M, Fagerberg I. Relatives’ experiences of encountering the older person with acute confusional state: Experiencing unfamiliarity in a familiar person. International journal of older people nursing. 2008;3:243–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2008.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersson EM, Hallberg IR, Edberg AK. Nurses’ experiences of the encounter with elderly patients in acute confusional state in orthopaedic care. International journal of nursing studies. 2003;40:437–448. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(02)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lou MF, Dai YT. Nurses’ experience of caring for delirious patients. The journal of nursing research: JNR. 2002;10:279–290. doi: 10.1097/01.jnr.0000347609.14166.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brajtman S, Higuchi K, McPherson C. Caring for patients with terminal delirium: Palliative care unit and home care nurses’ experiences. International journal of palliative nursing. 2006;12:150–156. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2006.12.4.21010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers A, Addington-Hall JM, McCoy AS, Edmonds PM, Abery AJ, Coats AJ, Gibbs JS. A qualitative study of chronic heart failure patients’ understanding of their symptoms and drug therapy. European journal of heart failure. 2002;4:283–287. doi: 10.1016/s1388-9842(01)00213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Namba M, Morita T, Imura C, Kiyohara E, Ishikawa S, Hirai K. Terminal delirium: Families’ experience. Palliative medicine. 2007;21:587–594. doi: 10.1177/0269216307081129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen MZ, Pace EA, Kaur G, Bruera E. Delirium in advanced cancer leading to distress in patients and family caregivers. Journal of palliative care. 2009;25:164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruera E, Bush SH, Willey J, Paraskevopoulos T, Li Z, Palmer JL, Cohen MZ, Sivesind D, Elsayem A. Impact of delirium and recall on the level of distress in patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Cancer. 2009;115:2004–2012. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buss MK, Vanderwerker LC, Inouye SK, Zhang B, Block SD, Prigerson HG. Associations between caregiver-perceived delirium in patients with cancer and generalized anxiety in their caregivers. Journal of palliative medicine. 2007;10:1083–1092. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD, Humphris G, Ingleby S, Eddleston J, Waldmann C, Gager M. Post-traumatic stress disorder-related symptoms in relatives of patients following intensive care. Intensive care medicine. 2004;30:456–460. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-2149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffiths RD, Jones C. Delirium, cognitive dysfunction and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2007;20:124–129. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3280803d4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, Annane D, Bleichner G, Bollaert PE, Darmon M, Fassier T, Galliot R, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Goulenok C, Goldgran-Toledano D, Hayon J, Jourdain M, Kaidomar M, Laplace C, Larche J, Liotier J, Papazian L, Poisson C, Reignier J, Saidi F, Schlemmer B. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2005;171:987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Day J, Higgins I. Adult family member experiences during an older loved one’s delirium: A narrative literature review. Journal of clinical nursing. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jocn.12771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toye C, Matthews A, Hill A, Maher S. Experiences, understandings and support needs of family carers of older patients with delirium: A descriptive mixed methods study in a hospital delirium unit. International journal of older people nursing. 2014;9:200–208. doi: 10.1111/opn.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bull MJ. Delirium in older adults attending adult day care and family caregiver distress. International journal of older people nursing. 2011;6:85–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2010.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stenwall E, Jonhagen ME, Sandberg J, Fagerberg I. The older patient’s experience of encountering professional carers and close relatives during an acute confusional state: An interview study. International journal of nursing studies. 2008;45:1577–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prorok JC, Horgan S, Seitz DP. Health care experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers: A meta-ethnographic analysis of qualitative studies. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne. 2013;185:E669–680. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.121795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epstein-Lubow G, Gaudiano B, Darling E, Hinckley M, Tremont G, Kohn R, Marino LJ, Jr, Salloway S, Grinnell R, Miller IW. Differences in depression severity in family caregivers of hospitalized individuals with dementia and family caregivers of outpatients with dementia. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry: official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;20:815–819. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318235b62f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liptzin B, Grob MC, Eisen SV. Family burden of demented and depressed elderly psychiatric inpatients. The Gerontologist. 1988;28:397–401. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pitfield C, Shahriyarmolki K, Livingston G. A systematic review of stress in staff caring for people with dementia living in 24-hour care settings. International psychogeriatrics/IPA. 2011;23:4–9. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zwijsen SA, Kabboord A, Eefsting JA, Hertogh CM, Pot AM, Gerritsen DL, Smalbrugge M. Nurses in distress? An explorative study into the relation between distress and individual neuropsychiatric symptoms of people with dementia in nursing homes. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2014;29:384–391. doi: 10.1002/gps.4014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Partridge JS, Martin FC, Harari D, Dhesi JK. The delirium experience: What is the effect on patients, relatives and staff and what can be done to modify this? International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2013;28:804–812. doi: 10.1002/gps.3900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bellelli G, Magnifico F, Trabucchi M. Outcomes at 12 months in a population of elderly patients discharged from a rehabilitation unit. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2008;9:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahoney Fi BD. Functional evaluation: The barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berg L. Clinical dementia rating (cdr) Psychopharmacology bulletin. 1988;24:637–639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jorm AF, Scott R, Cullen JS, MacKinnon AJ. Performance of the informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (iqcode) as a screening test for dementia. Psychological medicine. 1991;21:785–790. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700022418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bellelli G, Morandi A, Davis DH, Mazzola P, Turco R, Gentile S, Ryan T, Cash H, Guerini F, Torpilliesi T, Del Santo F, Trabucchi M, Annoni G, Maclullich AM. Validation of the 4at, a new instrument for rapid delirium screening: A study in 234 hospitalised older people. Age and ageing. 2014;43:496–502. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chester JG, Beth Harrington M, Rudolph JL. Serial administration of a modified richmond agitation and sedation scale for delirium screening. Journal of hospital medicine: an official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine. 2012;7:450–453. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O’Neal PV, Keane KA, Tesoro EP, Elswick RK. The richmond agitation-sedation scale: Validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2002;166:1338–1344. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, Thomason JW, Wheeler AP, Gordon S, Francis J, Speroff T, Gautam S, Margolin R, Sessler CN, Dittus RS, Bernard GR. Monitoring sedation status over time in icu patients: Reliability and validity of the richmond agitation-sedation scale (rass) JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:2983–2991. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.22.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bellelli G, Speciale S, Morghen S, Torpilliesi T, Turco R, Trabucchi M. Are fluctuations in motor performance a diagnostic sign of delirium? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2011;12:578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Jonghe JF, Kalisvaart KJ, Timmers JF, Kat MG, Jackson JC. Delirium-o-meter: A nurses’ rating scale for monitoring delirium severity in geriatric patients. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2005;20:1158–1166. doi: 10.1002/gps.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Creswll JW. Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. 2nd. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duppils GS, Wikblad K. Patients’ experiences of being delirious. Journal of clinical nursing. 2007;16:810–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse education today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gagnon P, Charbonneau C, Allard P, Soulard C, Dumont S, Fillion L. Delirium in advanced cancer: A psychoeducational intervention for family caregivers. Journal of palliative care. 2002;18:253–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morandi A, Davis D, Taylor JK, Bellelli G, Olofsson B, Kreisel S, Teodorczuk A, Kamholz B, Hasemann W, Young J, Agar M, de Rooij SE, Meagher D, Trabucchi M, MacLullich AM. Consensus and variations in opinions on delirium care: A survey of european delirium specialists. International psychogeriatrics/IPA. 2013;25:2067–2075. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213001415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bellelli G, Morandi A, Zanetti E, Bozzini M, Lucchi E, Terrasi M, Trabucchi M. Recognition and management of delirium among doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, and psychologists: An italian survey. International psychogeriatrics/IPA. 2014;26:2093–2102. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214001653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morse JM. The significance of saturation. Qualitative health research. 1995;5:147–149. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marhsall B, Cardon P, Poddar A, Fontenot R. Does sample size matter in qualitative research? A review of qualitative interviews in research. Journal of Computer Information Systems. 2013;54 [Google Scholar]